Tagged: Boston University Law School

The Problems With Euclidean Zoning

Since the1926 landmark Supreme Court case, Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365, it has been understood that the localities, municipalities, towns, and cities of the United States have the right to zone by dividing the town or community into areas in which specific uses of land are permitted. This is referred to as Euclidean zoning, and is considered the traditional and most common form of zoning in the United States. Euclidean zoning divides towns into districts based on permitted uses, and in so doing creates specific zones where certain land uses are permitted or prohibited. This can be helpful, as it enforces the separation of industrial land uses from residential land uses and can protect against pollution risks. However, Euclidean zoning has also exacerbated segregation issues, limited housing supply, and encouraged urban sprawl. Restrictions on minimum lot sizes, strict building codes, and other elements of Euclidean zoning have increased housing costs, limited new housing construction, worsened affordability issues, and increased the inequality divide in urban areas.

In Massachusetts, Euclidean zoning is the basis of General Law chapter 40A, the state’s zoning act. Chapter 40A encourages separation of land uses, and gives localities the ability to institute zoning within their borders. Given that Massachusetts has 351 towns, there are a wide variety of zoning bylaws throughout the state, based on each towns’ preferences and personal histories. Over time, Massachusetts’ state government has realized that the Euclidean zoning instituted by towns, aided and abetted by chapter 40A, has created neighborhoods that are dependent on cars and unsustainable. In an era of increased concerns about climate change, global warming, and greenhouse gas emissions, many people struggle to decrease their carbon footprint because they cannot get to the most basic goods and services, like groceries, schools, shopping, and work, without access to a car due to the enforced separation of uses within zoning districts. Separation of uses leads to urban sprawl, which is “the expansion of human populations away from central urban areas into low density monofunctional and usually car-dependent communities.” Increased urban sprawl has created patterns of development with extended infrastructure systems, increased impervious surfaces, and increased adverse impact on natural resources.

In Massachusetts, Euclidean zoning is the basis of General Law chapter 40A, the state’s zoning act. Chapter 40A encourages separation of land uses, and gives localities the ability to institute zoning within their borders. Given that Massachusetts has 351 towns, there are a wide variety of zoning bylaws throughout the state, based on each towns’ preferences and personal histories. Over time, Massachusetts’ state government has realized that the Euclidean zoning instituted by towns, aided and abetted by chapter 40A, has created neighborhoods that are dependent on cars and unsustainable. In an era of increased concerns about climate change, global warming, and greenhouse gas emissions, many people struggle to decrease their carbon footprint because they cannot get to the most basic goods and services, like groceries, schools, shopping, and work, without access to a car due to the enforced separation of uses within zoning districts. Separation of uses leads to urban sprawl, which is “the expansion of human populations away from central urban areas into low density monofunctional and usually car-dependent communities.” Increased urban sprawl has created patterns of development with extended infrastructure systems, increased impervious surfaces, and increased adverse impact on natural resources.

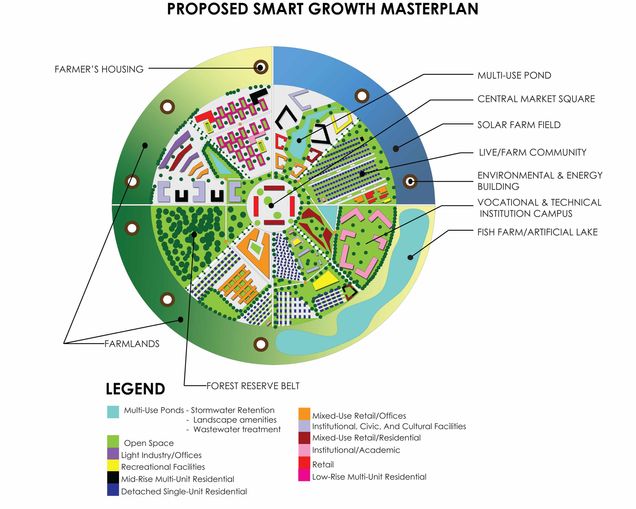

In response to concerns about Euclidean zoning, urban sprawl, and decentralization, Massachusetts’ legislature passed General Law Chapter 40R in hopes of encouraging changes in zoning and development patterns that would combat the impacts of Euclidean zoning. Chapter 40R’s purpose is to encourage smart growth and increased housing production in Massachusetts. Smart growth is a development principle that “emphasizes mixing land uses, increases the availability of affordable housing by creating a range of housing opportunities in neighborhoods, takes advantage of compact design, fosters distinctive and attractive communities, preserves open space, farmland, natural beauty and critical environmental areas, strengthens existing communities, provides a variety of transportation choices, makes development decisions predictable, fair and cost effective and encourages community and stakeholder collaboration in development decisions.”

The issue is that Euclidean zoning, is so ingrained it will be difficult for towns to change their entire structure. Chapter 40R tries to fit smart growth within the existing zoning structure by allowing towns and cities to create smart growth zoning districts in appropriate areas of the town. The state legislature attempts to help towns and cities ease into smart growth concepts by encouraging the development of a comprehensive plan, an affordable housing plan, and a vision plan for their community.

Massachusetts attempts to boost smart growth practices beyond using Chapter 40R. First is to amend the local bylaw. Communities could revise and amend their zoning bylaws to incentivize or require smart growth practices. Within zoning bylaws, communities can allow land uses “by-right” or “as-of-right”, which would permit land uses in a particular district without discretionary review. As such, the use may be regulated but cannot be prohibited. This method is the most predictable and easiest permitting method, so towns may permit land uses they want to encourage, like smart growth, as “by-right” uses. Using the “by-right” approach to make smart growth strategies easier to permit can make smart growth a more attractive option to developers who otherwise would have little incentive to use smart growth techniques when they are costlier and more time consuming to implement.

Another technique to boost smart growth would be to encourage site plan review as a procedure for getting smart growth developments approved. Site plan review is a “coordinated review of a development application between several local agents or boards.” Site plan review can potentially increase the amount and technical nature of the information submitted to the local boards, so communities should use caution in adopting this review technique. Site plan review can be used for “by-right” applications, as well as for special permit applications. “By-right” applications are more complicated, as the use is “by-right” and the reviewing authority does not have the power to deny the use. Once an application is deemed complete, the reviewing authority cannot deny the application, although the reviewing authority “may impose reasonable conditions that further the purposes and standards of the zoning code.” In short, site plan review, “as attached to by-right uses, should be viewed as essentially an administrative review,” and should be viewed as an opportunity for local boards to get more information about a development, not as a way to regulate or deny development.

Special permits were used in Chapter 40A to allow increases in the permissible density of population or intensity of a particular use; authorization of Transfer of Development Rights of land within or between zoning districts; and review of cluster developments, pursuant to the Subdivision Control Law. For smart growth, special permits can be used to enable innovative approaches, allow flexibility, encourage partnerships between developers and the community, provide incentives, and require specific design standards. Special permits are also useful for areas that are previously developed, and can allow redevelopment of preexisting nonconforming uses to encourage infill and active use of developed areas.

Chapter 40R’s main focus is on the use of zoning districts to encourage smart growth. This is done in conformity with Chapter 40A by allowing the creation of new districts or the use of overlay districts. Overlay districts lay on top of existing zoning and can cover many underlying districts or portions of underlying districts. This gives communities the ability to be flexible in regulating uses of land.

Euclidean zoning has been the norm in America for over ninety years, and while it has valuable features, its rigidity can and has exacerbated issues ranging from social issues like segregation, to environmental issues like urban sprawl. Changing this will be difficult, as Euclidean zoning has support for planning purposes as well as for class purposes, but techniques like smart growth, new urbanism, and statewide comprehensive planning can help combat these issues. Massachusetts has made a start at this by enacting Chapter 40R, but still has work to do on the statewide level to incentivize local communities to change their zoning or to make it easier for these zoning changes to occur.

Rachael Watsky graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Rachael Watsky graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

The U.S. Postal Service is Staying Alive (for now)

During the Spring, President Trump has brought to the spotlight a little-discussed, quite unsexy policy dilemma: how to save the U.S. Postal Service.

In a series of Tweets, the President accused Amazon of unfairly taking advantage of the U.S. Postal Service. The first of these Tweets appeared on his Twitter feed on March 29th, and seemingly accused Amazon of shirking its tax responsibilities and free-loading from the government delivery service:

“I have stated my concerns with Amazon long before the Election. Unlike others, they pay little or no taxes to state & local governments, use our Postal System as their Delivery Boy (causing tremendous loss to the U.S.), and are putting many thousands of retailers out of business!”

President Trump also seemingly accused the Washington Post, which is owned by progressive billionaire Jeff Bezos, of engaging in secret lobbying. Although it is not entirely clear to which type of lobbying President Trump was referring in his March 31st Tweets, he seems to imply that the Washington Post is Amazon’s lobbying arm or propaganda machine that is helping Amazon to rip off the post office:

“While we are on the subject, it is reported that the U.S. Post Office will lose $1.50 on average for each package it delivers for Amazon. That amounts to Billions of Dollars. The Failing N.Y. Times reports that “the size of the company’s lobbying staff has ballooned,” and that...

“…does not include the Fake Washington Post, which is used as a “lobbyist” and should so REGISTER. If the P.O. “increased its parcel rates, Amazon’s shipping costs would rise by $2.6 Billion.” This Post Office scam must stop. Amazon must pay real costs (and taxes) now!”

After several news outlets, including the New York Times, published articles rebutting his statement that Amazon is not paying taxes (Amazon paid $957 million in income taxes in 2017) and is costing the U.S. Post Office billions of dollars per year, President Trump again asserted that he was correct, tweeting in part, “Only fools, or worse, are saying that our money losing Post Office makes money with Amazon. THEY LOSE A FORTUNE, and this will be changed.”

A few days later, he again tweeted that, “Amazon should pay these costs (plus) and not have them bourne by the American Taxpayer. Many billions of dollars. P.O. leaders don’t have a clue (or do they?)!” However, if one thing is clear, it is that the U.S. Post Office is not funded through taxpayer dollars, but through its own revenue. Still, the President is correct that the post office is losing money every year, specifically $2.7 billion in fiscal year 2017. However, it is unlikely that the bulk of that loss was incurred by conducting business with Amazon.

According to the U.S. Postal Service’s annual report for fiscal year 2017, its biggest losses came from fluctuating forces outside of its control. “The controllable loss for the year was $814 million, a change of $1.4 billion, driven by the $775 million decline in operating revenue before the 2016 change in accounting estimate, along with the increases in compensation and benefits and transportation expenses of $667 million and $246 million, respectively.” Mail volumes declined by 3.6%, while employee benefits and transportation costs have increased. On the other hand, the report indicated that package mail is up by 11.4%, providing “some help to the financial picture of the Postal Service as revenue increased $2.1 billion.” However, that growth has not been able offset other losses.

In other words, package companies like Amazon may actually be helping the U.S. Postal Service, even if they are receiving discounted shipping rates. By law, the Postal Regulatory Commission ensures that all items sent through the U.S. mail are profitable. Therefore, even if the U.S. Postal Service gives a discount to Amazon, those shipments will still be profitable to some degree. Whether the U.S. Postal Service should charge higher rates is a separate issue.

Postmaster General and CEO Megan J. Brennan described the report’s findings as “serious though solvable.” So, how can the government hope to save an agency that has not had a net surplus since 2006? The U.S. Postal Service is hopeful that H.R. 756, which was introduced to the House of Representatives by Rep. Chaffetz in 2017, and is being sponsored by Rep. Garrett in 2018, will pass and provide some relief by reforming postal service benefits, operations, personnel, and contracting. In addition, the Postal Regulatory Commission must adopt a new pricing system to generate additional revenue.

Postmaster General and CEO Megan J. Brennan described the report’s findings as “serious though solvable.” So, how can the government hope to save an agency that has not had a net surplus since 2006? The U.S. Postal Service is hopeful that H.R. 756, which was introduced to the House of Representatives by Rep. Chaffetz in 2017, and is being sponsored by Rep. Garrett in 2018, will pass and provide some relief by reforming postal service benefits, operations, personnel, and contracting. In addition, the Postal Regulatory Commission must adopt a new pricing system to generate additional revenue.

U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders has also pitched some ideas in the past, which are now catching the public’s eye in light of the President’s recent Tweets. Senator Sanders recently told Vice News that the post office should expand its services to generate more revenue. For example, the U.S. Postal Service could offer gift-wrapping services to capitalize on package shipments around the holidays. Additionally, "[t]he postal service could make billions of dollars a year by establishing basic banking services so lower-income people have access not to these payday lenders but to someplace where they can be treated with respect."

This idea is not new. In fact, until 1966, many U.S. post offices did offer simple banking services. Moreover, other countries such as Japan, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy currently use similar systems of postal banking with success. Senator Sanders emphasized that the post office must survive or else Americans living in rural areas, where it is not profitable to deliver mail, will face a decrease or elimination of mail services.

One former postmaster added that “[a]bsent a public infrastructure like the postal service network, it’s likely that both of these private sector firms (Fedex and UPS) would either refuse to serve many areas of the country or they would use their powers as an oligopoly to control prices.” In other words, if the U.S. Postal Service goes out of business, other mail carriers may be unable to fill the gap, or may only do so at inflated rates.

With so much at stake, it is daunting to imagine America without the U.S. Postal Service. We can only hope that Congress will step in and make the necessary reforms before it is too late.

Caitlin Britos anticipates graduating from Boston Univeristy School of Law in May 2019.

Caitlin Britos anticipates graduating from Boston Univeristy School of Law in May 2019.

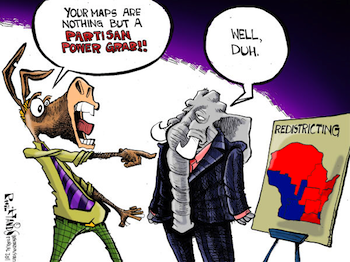

Can Partisan Gerrymandering be Stopped?

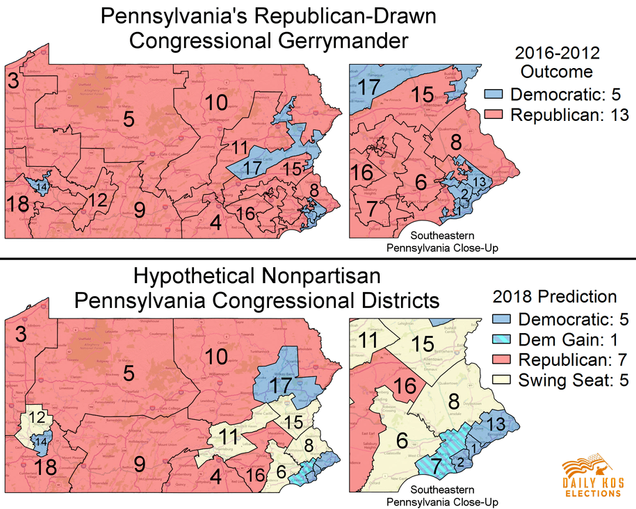

Attention to partisan gerrymandering has heightened as the next wave of redistricting fast approaches and the Supreme Court’s 2017-2018 docket included two cases regarding the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander. Following the release of the 2020 census, states will set out to redraw their district maps. States redistrict at least every ten years. The 2010 redistricting results are described as the most extreme partisan gerrymandering in our country’s history. The 2010 maps have a heavy Republican partisan advantage, as evidenced by the 2012 election results with Republicans gaining a 234 to 201 seat advantage in the House of Representatives despite Democrats winning 1.5 million more votes than Republicans. The Republican partisan advantage has remained strong. The Brennan Center for Justice has predicted that in the 2018 midterm elections Democrats will need to win by a margin of nearly 11 points to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. Democrats, however, have not won by a margin this large since 1974. Following years of heavily gerrymandered districts, a supermajority of Americans have indicated support for the Supreme Court to bring an end to partisan gerrymandering, yet the Court failed to take action this year.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering seems to fly in the face of democracy. Voting is a fundamental right and electing who you want to represent you in office is a fundamental part of democracy. Legislatures that scheme, plan, and manipulate maps to benefit one party over another can undermine the purpose of democracy. Some of this scheming, planning, and manipulating is self-interested as legislatures try to protect incumbents and create safe districts, but can also serve the purpose of entrenching a political party’s majority until the next redistricting cycle. Both parties, Republicans and Democrats, have enjoyed the benefit of partisan gerrymandering when given the opportunity.

While the Supreme Court has indicated that some level of partisan gerrymandering may be unconstitutional, it has yet to explain when the constitutional line has been crossed. This term, the Supreme Court took up the question of partisan gerrymandering for the first time in more than a decade. The two cases before the Supreme Court were Gill v. Whitford and Benisek v. Lamone. The Supreme Court was asked to answer when partisan gerrymander crosses the constitutional line. Gill v. Whitford challenged a statewide map that has been deemed among one of the worst partisan gerrymandered maps in the country, with a significant Republican partisan advantage. Benisek v. Lamone challenged one congressional district in Maryland, with a significant Democratic partisan advantage. Some speculated that the Court took up both cases to deter an appearance that the Supreme Court prefers one party over the other. Another reason may be that the Wisconsin case was a challenge to a statewide map compared to the Maryland case challenging one congressional district.

The appellants attorney in Gill v. Whitford argued during oral arguments (see, page 62) that the Supreme Court is the only institution to put an end to partisan gerrymandering. The Court, however, sidestepped the entire issue by unanimously finding the Gill plaintiffs did not have standing, and that the challengers in Benisek had waited too long to seek an injunction blocking the district. The Supreme Court’s silence allows legislatures to continue to strategically gerrymander.

While the country waits on the Supreme Court to provide an answer on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander, some states have attempted to take partisanship out of the process by using redistricting commissions, while others suggest that computers with algorithms should produce the maps. Yet, neither of these options individually seem to completely insulate redistricting from politics.

States have adopted redistricting commissions with the intention to remove partisanship from the redistricting process. However, this has often proved difficult to achieve, as finding non-partisan committee members is difficult and oftentimes the commission is appointed by partisan members, such as elected representatives and governors. States use different types of commissions and may only use a commission for redistricting the state map or congressional map. About 23 states use commissions for the state legislative maps and about 14 states use commissions for the congressional maps. The redistricting commissions can take the form of an advisory commission that makes suggestions to the legislature, a backup commission that draws the map if the legislature fails to redistrict, or as having the primary responsibility of drawing the map.

Even states that use independent redistricting commissions have had difficulties completely insulating the process from politics. For instance, in 2011, Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission chairwoman was removed by the Republican Governor and the Republican-controlled State Senate. The Governor accused the chairwoman of skewing the process for Democrats. The Arizona Supreme Court, however, reinstated the chairwoman and the United States Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s independent redistricting commission as a legitimate way to draw district maps. Although some states are moving toward redistricting commissions as a way to insulate the process from politics, these commissions are “only as independent as those who appoint it.”

While technological advances have been thought to help parties gerrymander more effectively, some suggest that similar technology could take politics out of the process with the proper algorithms. Brian Olson, a Massachusetts software engineer, wrote an algorithm to create “‘optimally compact’ equal-population congressional districts.” Olson prioritized the compactness requirement in an effort to reflect “actual neighborhoods” and because dramatically non-compact districts can be a “telltale sign of gerrymandering.” However, political scientists are skeptical about an algorithm prioritizing compactness, because it ignores other important factors, such as community of interest. Furthermore, someone needs to set the algorithm and there can be infinite map results. Thus, without very strict restrictions and guidelines, setting an algorithm and picking the map can still be an inherent gerrymander.

Removing politics completely from the redistricting process appears to be nearly impossible. Partisanship is deeply entrenched in the process, and dates back to even before the coined term “gerrymander.” Redistricting commissions do not always guarantee a partisan free redistricting effort, and while technology offers an alternative to human map drawing, humans are still making the final decision. Some combination of these efforts may help to lessen the amount of politics used in the redistricting process or lessen the appearance of partisanship, but are unlikely to completely end partisan gerrymandering all together.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Arizona’s Teacher Strikes: The End or Just the Beginning?

For six school days in late April and early May, teachers across the state of Arizona walked out of their classrooms to demand better pay, more classroom funding, and other concessions from governor Doug Ducey (R) and the Republican-controlled state legislature. These teachers, inspired by similar walk-outs in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Kentucky, brought their “outside voices” together to call for change. In the early morning hours of May 3, Ducey signed the new state budget that gave teachers a raise. But, the bill fell short of meeting the walkout organizers’ other demands. Some have said the #RedforEd movement failed because it did not deliver on all of the group’s demands. Still, this strike was just the beginning.

It is important for me to be transparent about my personal connections to this issue. My mother is a life-long public school teacher, who recently retired after over 25 years of teaching in schools across Arizona. As part of Teach for America, I spent three years teaching in the Littleton Elementary School District, the same district where #RedforEd organizer Noah Karvelis teaches, although Mr. Karvelis started teaching after I left for law school. During my first two years of teaching, I earned my Master’s degree in secondary education from Arizona State University. And while I moved across the country to attend law school in Boston, I have kept in touch with many of my former colleagues in Arizona.

The issues with education funding in Arizona started in 2008, while the country was reeling from the recession. As states across the country scrambled to fix their budgets, Arizona’s schools took a big hit. Ten years later, while the economy has recovered, funding for Arizona’s schools didn’t. According to a report by the state’s auditor, schools were receiving less inflation-adjusted dollars per student in 2017 than they were in 2008. During that time, the state has seen its income limited by a number of tax cuts, the largest of which have gone to corporations. Despite promises, economic research has indicated that the cuts have not stimulated economic growth, resulting in decreasing government revenue. All this has translated into horrible conditions in many schools across the state.

The combination of the lowest teacher salaries in the country, low education funding, and successful walkouts in other states urged Arizona’s educators to take action. The group Arizona Educators United, which started the #RedforEd movement, laid out five demands: 20% raises for teaching & certified staff; pay raises for classified staff (janitors, paraprofessionals, secretaries, etc.); restoring classroom funding to 2008 levels; no new tax cuts until Arizona’s per-student funding reaches the national average, and annual raises for teachers until salaries reach the national average.

The movement’s hashtag, #RedforEd, started as a way to draw attention to the lack of education funding. Teachers began with “walk-ins” – they arranged to arrive at school early and stand just outside their school’s gates, wearing red shirts and waving signs. The walk-ins were aimed at building community support. Teachers also protested outside the capital during a “teach-in” on March 28 after the school day ended. The walk-ins continued for another month and, when the state legislature wasn’t receptive, the strikes began on Thursday, April 26.

After nearly 13 hours of debate, Governor Ducey signed a new state budget that included nearly $273 million for teacher pay raises. That will only amount, however, to a 9% raise this year. Governor Ducey has plans to provide 5% raises in each of the next two years, in addition to the 1% raise teachers saw at the start of the last school year. But, this plan has a big problem. The legislature passes a new budget each year. So, while Ducey has “plans” to provide a 20% raise by 2020, that plan is completely out of his control because the decision ultimately lies with the legislature.

There are a number of other concerns that the teachers have with Ducey’s deal. The budget does nothing to raise per-pupil spending, increase pay to support staff, or reduce the state’s student-to-counselor ratio. While the American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students per counselor, Arizona averages 924 students per counselor. A Democratic representative, Mitzi Epstein, had offered an amendment that would mandate a 250:1 student-to-counselor ratio, but the amendment failed.

While the budget itself certainly contained far less than #RedforEd supporters had hoped for, the fight is far from over. There are a number of ballot measures this November that could take Arizona’s education system in radically different directions. First, Proposition 305 asks voters whether they want to keep Senate Bill 1431 in place. That bill expanded what are formally called “Empowerment Scholarship Accounts” (“ESAs”) but more commonly known as school choice “vouchers.” While the two terms are not mere synonyms because they allocate money somewhat differently, the net result is that ESAs may be used by parents to send their child to private schools (including religiously affiliated schools). The money for ESAs is taken from public schools which, as stated, are grossly underfunded.

Organizers are also seeking petition signatures to place another initiative on the ballot related to education funding. The “#InvestInEd” ballot measure, which has not been given a number yet because it is not yet formally on the ballot, calls for tax increases on income over $250,000 for individuals or $500,000 for married couples. The web page in support of the ballot measure states that “[t]he higher rates are only paid on the income above those amounts.” Perhaps most importantly, funding secured through a ballot measure such as this one “cannot be taken away by the legislature.”

Finally, the #RedforEd movement has even driven some teachers to take more direct action. After spending nearly a week at the Capitol pleading with legislators to take action, several educators are running for elected positions themselves. The article by the Arizona Capitol Times identified former teachers running as both republicans and democrats for positions in the state house and senate, as well as local school boards.

The flurry of activity around education funding in Arizona makes a bold statement: this issue is not going away. While the strikes may be over and the new budget is signed, teachers have made clear that this will be a big issue come November. Beyond the ballot initiatives and teachers running for elected office, Governor Ducey is up for reelection. The #RedforEd movement unquestionably fell short of their goals – the last answer on the Arizona Educators United “FAQ” page makes that clear. But, to say that the movement died when the strikes ended is to underestimate the political will of angry teachers. Time will tell, but I think the movement for education improvement in Arizona is far from over.

David Bier anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Mental Illness and Gun Violence: What’s Really Responsible?

You’ve heard it all before. In fact, you’ve heard the same arguments repeated back and forth so many times you have memorized them yourself. The cycle goes like this: There’s a mass shooting, then in the tragic aftermath, the liberal and conservative pundits begin repeating their arguments left and right. Usually, on the conservative right there are calls for mental health reform and on the left, liberals agree that we need to address mental health, but point to gun access as the key issue to prevent these tragedies from happening. The rest of us, the general population, are left somewhere in between. We point fingers like everyone’s to blame, but we take action like nobody is responsible. That is to say, we take very little action at all.

Although this cycle has repeated itself to the point of feeling like a broken record, it’s important that we not get stuck like one. After all, the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over-and-over again while expecting a different result. Where some blame the mentally ill and some blame guns, it is important to step back and reframe our arguments to see the issue of gun violence in a different light. Maybe the solution, as is often the case, lies somewhere in between.

The tragedy in Parkland has energized this debate to unprecedented levels, but has also brought with it many familiar arguments. In particular, recent calls from President Trump to strengthen limitations on the ability of the mentally ill to access firearms gives us cause to reevaluate his premise that mental illness is associated with gun violence. President Trump’s critique is founded on a commonly shared belief among the majority of Americans. According to a Pew Research poll in 2017, 89% of people across the political spectrum favor placing increased restrictions on the ability of the mentally ill to purchase firearms. This commonly held belief across the political spectrum forces us to ask ourselves: What is the real relationship between mental illness and gun violence?

What do the Numbers Say?

The evidence suggests that we may be biased when it comes to our perceptions of the mentally ill and the potential for persons dealing with mental illnesses or disorders to exhibit violent tendencies. In fact, a 2013 national public opinion survey (p.367) found that 46% of Americans believe that persons with mental illness are “far more dangerous than the general population.” However, the public perspective is vastly distinct from reality. Another study (p.241) demonstrates that between 2001 and 2010, “fewer than 5% of the gun-related killings in the United States… were perpetuated by people diagnosed with mental illness.” People are far more likely to be killed by a person with a gun that does not have a mental illness, than someone that does have a mental illness.

While mental illness is not strongly correlated with gun violence, there are other conduct measures that appear to be strong predictors of such violence. Three conduct measures in particular that are powerful are past acts of violence/criminal history, a history of domestic violence, and substance abuse.

First, with regard to a history of violence, the American Psychology Association issued a report (see p.8) that concluded based on longitudinal studies, “The most consistent and powerful predictor of future violence is a history of violent behavior.” One article from Wisconsin Public Radio affirms this trend in reporting that for gun homicides in Milwaukee about, “93 percent of our suspects have an arrest history.” Although the Milwaukee sample is small and not entirely representative of the entire United States, such a high correlation is worthy of our attention in considering factors for reevaluating our gun policies.

Second, when it comes to the correlation between domestic violence and mass shootings or gun violence, the evidence is even stronger. According to a study quoted in the New Yorker, “Of mass shootings between 2009 and 2013, 57 percent involved offenders who shot an intimate partner and/or family member.” Further, a report from Everytown for Gun Safety shows that persons with a history of domestic violence account for “54 percent of mass shootings between 2009 and 2016.”

Third, with regard to substance abuse, a study (p.242) by Dr. Jonathan Metzl, an often quoted figure in studying the causes of gun violence in the United States, found that, “[A]lcohol and drug use increase the risk of violent crime by as much as 7-fold, even among persons with no history of mental illness.” According to the same study, “serious mental illness without substance abuse is ‘statistically unrelated’ to community violence.” In other words, substance abuse increases an individual risk of violence in general, including an increased risk of gun violence.

States Offer Pragmatic and Nuanced Solutions

However, correlation does not equal causation. Many of the current studies on the causes of gun violence and mass shootings face limits (p.240) in this particular regard. However, the low statistical correlation indicated in multiple studies between mental illness or disorders and gun violence are informative. The fact that there are other risk factors that are strong predictors of violence generally and gun violence specifically point to where our attention is likely better directed in trying to rework gun laws in a manner that will work for everyone.

The Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence points to one such unique legal mechanism adopted in Oregon, Washington and California, which have adopted laws for Extreme Risk Protection Orders (“ERPOs”). These laws allow family members or law enforcement officers to petition a court to keep guns away from someone going through a crisis. The laws are geared toward the principle that family members are best able to gauge changes in an individual’s behavior that could pose a serious risk of harm. Petitioners under these laws still have the burden of providing sufficient proof that the individual poses a risk of danger to themselves or others. ERPOs are also only temporary, but may vary in length. For longer protective orders, more compelling evidence must be offered that the person poses a risk of harm to themselves or others.

Oregon offers another pragmatic solution in its closing of the “domestic abuser loophole” through passage of a recent state law. Under the 1996 Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban, domestic abusers are banned from owning or possessing a gun. However, the federal ban only applies to someone if they are married, living with, or have a child with the victim of the abuse. The wording of the law creates the “domestic abuser loophole,” which means that someone who is not living with their significant other and does not meet any of the other mentioned criteria, but who abuses their significant other, can still buy a gun. Oregon’s new law prohibits anyone convicted of a crime of domestic violence from owning or possessing a gun, regardless of whether or not that person lives with their significant other.

These new state laws are just examples of a number of other pragmatic and nuanced policy solutions that are geared toward preventing future gun violence while avoiding burdensome restrictions on the Second Amendment rights of the vast majority of Americans. Such solutions demonstrate our capacity to tackle the problem of gun violence in new and creative ways, while still preserving individual freedoms. Finally, these laws represent effective solutions that are based on empirical evidence about true risk factors for gun violence and not on ill-founded stigmas. A path forward on fixing our gun laws exists, but to move forward we must set aside our preconceived notions and work together to promote innovative solutions that protect both our rights and our safety.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

New York State’s Missed Opportunity On Early Voting Propositions

It’s no secret that the United States has one of the lowest voter turnout rates of any established democracy. Data provided by the Pew Research Center shows that out of the 35 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States places 28th for voter turnout. Only a little more than half of the U.S.’s voting age population participated in the 2016 elections. One reason for low voter participation that reformers consistently point to is the fact that Election Day is on a Tuesday in November.

Americans have been voting on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November since 1845 when Congress decided to set a national election day. In the 1840s, elections on a Tuesday made sense. People traveled by buggy and would make the journey into town for the market which was generally held on Wednesdays. By setting election day on Tuesday, Congress made it convenient for people to vote because they were in town anyways. However, today many people work on Tuesdays which makes less it a less practical day of the week to have an election than it was in 1845.

One way states have dealt with the difficulties created by Election Day falling on a Tuesday has been to develop provisions for early voting. Early voting allows people to cast a ballot in person at either an elections office or other specified location at some point before the federally designated Election Day. As of 2017, 37 states allow registered voters to vote during a specific period of time before Election Day, and 22 states provided an option to vote during the weekend. Early voting begins in some states as early as 45 days before the election or as late as the Friday before election day, although the average early voting start date is 22 days before Election Day. Generally early voting ends a few days before Election Day.

New York is one of only thirteen states that does not allow early voting. It does have absentee ballots, but allows voters to use them only if they are out of the county or otherwise unable to vote on election day as a result of illness or disability. New York has dismally low voter participation rate, and in the 2016 election New York state ranked 42nd in voter turnout with only about 59% of eligible voters voting. For years there have been attempts to update New York’s voting laws, but resistance from the Republican controlled Senate has led to the failure of these bills.

However, that may soon change. Since early 2017 there appears to be increased attention to and political will for election reform. In January of 2017, former Attorney General Eric Schniederman introduced the New York Votes Act which included provisions for automatic registration of eligible voters, early voting, and no-excuse absentee voting. The bill was sponsored by the Chairman of the Election Law Committee, Assemblyman Michael Cusick (D-Statent Island). The bill is currently in committee.

In January of 2018, Senator Brian Kavanagh (D-Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan) introduced Senate Bill S7400A which would create an eight-day early voting period that would be funded by the state. The bill is currently in the election law committee, and has received support from Democrats including Democratic Conference Leader, Andrea Stewart-Cousins (D-Yonkers), a cosponsor of the bill. Senator Stewart-Cousins called New York voter turnout “extremely embarrassing” and stated that “Our bills will modernize voter registration, implement early voting, protect voters' rights, and cut red tape which has kept far too many New Yorkers from exercising their constitutional right.”

Republicans have also introduced their own election reform legislation. Senate Bill S7212 sponsored by Republican Senator Betty Little (R- Queensbury) would allow early voting beginning 14 days before the general election. Senator Little remarked “The people this would help the most are the families, people who are working with children in school, with sports activities and homework…They intend to vote; they just don't get there that day." Assemblywoman Nily Rozic (D, WF-Fresh Meadows) sponsored the Assembly version of this bill.

On February 12, 2018, drawing on aspects of both Senator Kavanagh’s bill as well as Senator Little’s bill, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a 30-day budget amendment which would provide approximately $7 million in FY2019 for counties to run early voting programs. Governor Cuomo’s plan calls for counties to provide early voting opportunities during the twelve days prior to Election Day, and requires that voters have at least eight hours on weekdays and five hours on weekends to cast their vote. Counties must also provide at least one early voting site for every 50,000 residents, the location of which will be determined by the bipartisan County Board of Elections.

Several groups have expressed support for early voting including labor unions, good government organizations, and the League of Women Voters. Proponents of early voting claim that if people were able to vote at a time that was more convenient for them, there would be broader participation. However, some opponents of early voting have argued that early voting may actually cause lower voter turnout because people will not feel the same social pressure to vote as they do when they are only able to vote on one day. Additionally, people who vote early may not have the same information as people who vote on Election Day because advertising and campaigning intensifies as Election Day approaches. In the past Republican leaders in the Senate have expressed a hesitancy to change the system, though the spokesman for Senate Republican Leader John Flanagan (R- Suffolk County) recently stated “Our conference has supported electoral reforms in the past, and we would expect to do so again…But we have not discussed that specific proposal recently."

Whether New York will ever adopt early voting is still unsettled. The legislature voted on the Governor’s budget in late March, but the Senate majority removed the early voting provisions. In mid-April, the Assembly passed election reform bills to authorize 7 day advance voting, overhaul the voter registration process and allow for online registration. The Senate referred the bills to the Election Committee, and then on June 20, the session came to a quiet end without any action on voting. Speaker Heastie does not anticipate any more legislative meetings until the new legislature is seated in January 2019. Perhaps the elections will break the logjam in the Senate and early voting in New York will become a reality.

Meghan Hayes anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Meghan Hayes anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

A Practical Guide to Surviving Your First Legislative Externship

I have done quite a few externships over the years in a variety of fields. However, working at the State House has kept me on my toes. I had so much to learn. I had a great boss and that helped. But looking back, I wish I had prepared a little better. I had no legislative experience and was not from a state that did a lot of state government work. So here are a few tips I would give to those who are new to this environment.

- Learn a little about your state!

When I started my externship, I did not know anything about Massachusetts. I mainly came here to go to school and that was it. However, since working at the State House, I wish I knew more about the state and my senator’s district. I spent a lot of time googling regions of Massachusetts and asking questions. So if you have a legislative externship, feel free to do your research. Learn about the state and who are the constituents. Does a state have a larger rural population or an urban population? What are the industries and demographics of a state? Knowing these things will enhance your experience and give context to your interactions at the state house.

- Understand that state government is different from federal government

Being from Washington, DC, I had no concept of how state government worked. In my area, everything is concentrated in either the federal government or the local government. I had always viewed the federal government as a constant stalemate or arguing about things that did not matter. I thought that senators were inaccessible and expected that from my externship. However, I was wrong. Senators in Massachusetts are generally pretty accessible and enjoy hearing from their constituents. I had no idea that a state senator would be different from a US senator. But while working for a state senator, I felt as though I was actually contributing to tangible changes. This is a super rewarding feeling that you won’t get anywhere else.

- Get familiar with the State House Website and State House News.

I believe this is one of the most important lessons I learned while working at the State House this year. The fastest way to learn about the State House is to read State House News and the State House website. Boston University School of Law provides its students with a free subscription to State House News. If you want to find out anything about what’s happening in the state house, State House News is the place to look. They have information on bills, legislators, and general news. The State House website will hold all of the bill before the legislature and the general laws. I spend most of my time on that website. Feel free to check out the site before you start your externship. That way you are ready to hit the ground running.

- Never miss a meeting.

Some people hate meetings, but at your legislative externship you will learn to like them. One, they are much more fun than normal meetings at the office. Second, they are actually useful. Most of your meetings with either be with lobbyists or constituents. Making sure you are present for these meetings will teach you a lot about your senator’s district and their priorities. This was the forum where I learned the most. So, make sure you are there!

- Be open to saying I don’t know.

This is probably self-explanatory, but just be honest if you don’t know something. Your supervisor knows that this is an externship and that you are here to learn. Be honest about your experience level and don’t be afraid to ask questions. This externship is designed for you to learn so take advantage of it.

Externships are a serious investment of time and your tuition dollars. The Massachusetts State House can be an awesome place to work and to learn. Learn a lot, enjoy the experience, and make the most of it!

Nia Johnson anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Nia Johnson anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Massachusetts’ “Death By Dealer” Bill is the Wrong Opioid Policy

On January 30, 2018, the Massachusetts Joint Committee on the Judiciary heard testimony on S. 2158, An Act Updating Laws Relating to Dangerous Drugs and Protecting Witnesses. Despite its relatively innocuous title, the bill, proposed by Governor Charlie Baker, represents a substantial scaling up of the War on Drugs in the Commonwealth.

Like many other states, Massachusetts is in the midst of a public health crisis. The opioid-related death rate in the state has surpassed the national average, with a nineteen percent increase in overdose deaths between 2015 and 2016. In addition, three-quarters of opioid-related deaths in 2016 involved fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is roughly 50 times more potent than street heroin. As opioid overdoses decimate local communities, officials are understandably investigating ways to curb the epidemic, and one solution, to which legislatures are increasingly turning, entails drastically increasing punishment for drug crimes that result in death.

For decades, federal prosecutors have been able to pursue stringent penalties in cases of “death by dealer.” Passed by Congress in 1988 in response to the highly publicized death of a University of Maryland basketball star who overdosed on cocaine just days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics, the so-called “Len Bias” law sets mandatory minimum sentences for selling drugs that lead to another person’s death. More recently, twenty states have adopted analogous laws, and several others have “McGyvered” existing homicide statutes—e.g., reckless homicide and felony murder—to prosecute the same offense. With Governor Baker’s bill, Massachusetts joins a number of additional states with pending legislation that would allow prosecutors to charge drug sellers with murder or manslaughter.

For decades, federal prosecutors have been able to pursue stringent penalties in cases of “death by dealer.” Passed by Congress in 1988 in response to the highly publicized death of a University of Maryland basketball star who overdosed on cocaine just days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics, the so-called “Len Bias” law sets mandatory minimum sentences for selling drugs that lead to another person’s death. More recently, twenty states have adopted analogous laws, and several others have “McGyvered” existing homicide statutes—e.g., reckless homicide and felony murder—to prosecute the same offense. With Governor Baker’s bill, Massachusetts joins a number of additional states with pending legislation that would allow prosecutors to charge drug sellers with murder or manslaughter.

While these laws may seem like a good idea at first—as a way to cripple the organized drug trade and to give prosecutors new tools to attack upper echelon drug traffickers—the criminalization of accidental overdose has a number of possible unintended consequences. Massachusetts legislators should carefully consider these effects that may backfire and exacerbate an already dire situation.

Although proponents argue that drug-induced homicide law will prevent future drug trafficking, there is broad consensus that harsh sentences have minimal, if any, deterrent effect. Contrary to conventional wisdom, studies have found that, among individuals facing drug-related charges, variations in prison and probation time have no impact on recidivism rates. The focus on supply reduction also seems misplaced: many studies suggest that market demand for drugs drives a continuous “replacement effect,” such that incarcerating drug dealers simply “open[s] the market for another seller.” Instead, such policies may inadvertently increase drug-related violence and lead to dangerous fluctuations in the contents of street drugs.

Drug-induced homicide laws also risk undermining Good Samaritan policies. As overdose deaths skyrocket, 37 states, including Massachusetts, have enacted laws to reduce the legal barriers to calling 911 in the event of an emergency. Most of the laws are limited to drug possession, however; they do not encompass drug selling or homicide. Although popular imagination places drug users and drug sellers in separate buckets, reality proves far blurrier: drug users frequently participate in the supply side of the market—whether by actively selling drugs or by helping in some way, such as acting as a lookout—in order to support their habits. Ostensibly intended to prosecute high-level drug suppliers, in practice, these statutes often ensnare family, friends, and acquaintances who supplied the drugs and who themselves may have a substance use disorder. In Wisconsin, an analysis of the 100 most recent drug-induced homicide prosecutions found that “nearly 90% of those charged were friends or relatives of the person who died, or people low in the supply chain who were often selling to support their own drug use.”

While prosecutors talk about “aggressively prosecuting those people that peddle the poison in our community,” users counter that “every drug-induced homicide charge that is made sends a ripple through the using community to not call 911 and might result in somebody else's death.” In fact, a recent study found that a majority of surveyed drug users feared calling 911 during an overdose due to concerns about criminal repercussions. Overall, then, treating overdose deaths as crime scenes and prosecuting overdose witnesses as perpetrators of murder or manslaughter limits the potential benefits of Good Samaritan legislation and other efforts to reduce overdose deaths.

Finally, punitive approaches, which place the blame for overdose deaths on drug sellers, focuses on the wrong problem. Criminal sanctions have the benefit of immediate visibility—they make it appear to constituents that policy makers are doing something. Public health approaches, on the other hand, are virtually invisible because, if successful, the harms that they target will never materialize. This “prevention paradox” often leads policy makers towards individualized, instantly tangible solutions to complex problems such as drug-induced homicide laws.

The opioid crisis is, fundamentally, a structural issue, rooted in poverty, lack of opportunity, and social isolation. Structural issues require structural solutions. Legislators are understandably grabbing at any and every straw to quell what seems like an intractable problem, but, at a time when much of the country seems poised to approach problematic substance use as a health issue, rather than a criminal one, it is critically important that Massachusetts policy makers carefully consider the ways in which S. 2158’s drug-induced homicide provision might backfire.

Rather than focusing on misguided “quick fixes” that further criminalize vulnerable populations, legislators should, instead, redirect their energies towards public health strategies with demonstrated effectiveness in reducing fatal overdoses. These include implementing comprehensive, evidence-based addiction prevention initiatives; increasing overdose education and naloxone access; promoting the use of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders; and expanding and maintaining insurance coverage for addiction treatment. The United States has been trying to arrest its way out of substance use and addiction for decades, and today’s crisis attests to the futility of that approach. If our policy makers are serious about ending the opioid epidemic in the Commonwealth, they need to shift their focus from policing and prisons to people and public health.

Alexandra Arnold anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Alexandra Arnold anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

The End of Dams: Removal and River Restoration

America has a love-hate relationship with dams. As a nation, America has built “on average, one dam per day since the signing of the Declaration of Independence.” Individually, dams have existed in America since long before the states revolted against Great Britain. Massachusetts has the oldest dam listed in the National Inventory of Dams, the Old Oaken Bucket Pond Dam (see slide 21) in Plymouth County, which was built in 1640. The dams started small, as mill dams on small streams for specific towns, but have grown in size to hundreds of feet tall, damming some of the largest rivers in America. Dams are often used (see slide 14) for hydroelectric power, irrigation, flood control, and the vaguely defined “recreational use.” Despite this love of “biggering and biggering”, America has failed to maintain many of the dams constructed, leading to the dangers we now face on a local, state, and federal level. Dams are also harmful to rivers, causing a depletion of fisheries, degradation of river ecosystems, and degradation of river water quality. This article will briefly discuss what Massachusetts has done to address these issues, mainly by removing dams that are a hazard.

In Massachusetts, a failure to maintain dams has led to crises where towns have been evacuated at the threat of a dam bursting. An example is the Whittenton Pond Dam, in Taunton, Massachusetts, where in 2005, after days of rain, the 170-plus-year-old dam nearly collapsed. Close to 2,000 residents were evacuated due to fears of a six-foot high wall of water rushing through the town. Thankfully, the local government and the state were able to mobilize an emergency response team that stabilized the dam; at a cost of over $1.5 million. If the dam had collapsed, the damage, physically and financially, would have been far greater.

Massachusetts has approached dam removal in multiple ways. After the Whittenton Pond Dam emergency, the Office of Dam Safety was rejuvenated and given funding to evaluate the nearly 3,000 dams, in varying states of disrepair, spread across the state. Massachusetts passed “An Act Further Regulating Dam Safety, Repair and Removal”, emergency legislation to increase dam safety and encourage dam removal, in late 2012. The Act passed with support from multiple parties and interests, including the Nature Conservancy, municipal associations, water suppliers, engineering professionals, and other conservation organizations. This law gave various commissions and agencies more authority to respond to dam repair and removal issues, and set up ongoing funding for the repair or removal of dams, seawalls, and other water infrastructures. The various authorities must submit an annual report on the status of the dams in the state. The Massachusetts Office of Dam Safety, the Division of Ecological Restoration, and other agencies are required to assess dams, ensure dam owners have emergency action plans (EAPs), ensure that dam owners address safety issues, establish an inspection process and schedule for dams, and assess fines for noncompliance. Massachusetts provides grants for design costs of removal projects, which is an additional incentive to encourage dam owners to remove dams in noncompliance or that no longer perform the function for which they were built.

Massachusetts G.L. c. 29, §2IIII established the Dam and Seawall Repair or Removal Fund, which operates under the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs and offers grants to local government bodies, charitable organizations, and private dam owners to finance inspection, repair, and removal projects for dams, seawalls, jetties, revetments, retaining walls, levies, and other means of flood control. Often, it is less expensive to remove an old, dilapidated structure than to repair it, so owners will perform removal projects rather than repair projects. Along with removing the dam, the legislature has delegated power to administrative agencies to help encourage restoration of the river after the dam is removed. One of the earliest dam removal projects in Massachusetts (see page 118) was intended to increase public safety and river accessibility for recreation, but also to increase bordering vegetated wetland on the river and to improve and restore access to cold-water habitat.

So far, Massachusetts has avoided removing dams that were built for flood control purposes, opting instead to encourage repairs. However, Massachusetts considers dams built for nearby industrial use, other hydropower purposes, irrigation, or recreational use as fair game for removal. This decision is consistent with policy for many states and the federal government. This policy is especially relevant when the use has been abandoned, public safety is at risk, or the dam is in disrepair and the owner either cannot be found or refuses to pay to maintain the dam.

Thankfully, Massachusetts is well on its way to removing the more problematic dams and restoring its rivers and streams. The Division of Ecological Restoration has assisted multiple dam owners with the removal and restoration process, including the Whittenton Pond Dam that nearly collapsed in 2005. After the passage of the Dam Safety Act, the Whittenton Pond Dam was removed in 2013-2014 as part of an initiative by the Division of Ecological Restoration and the Mill River Restoration Project. The Morey’s Bridge Dam had a fish ladder constructed rather than have the dam removed. Two other dams on the Mill River, the Hopewell Mills Dam and the West Britannia Dam, have either been removed or are in the process of being removed. Upon completion, over 50 miles of stream habitat and 400 acres of pond habitat will open up, rejuvenating the cold-water fisheries and allowing river herring (an endangered species), American eel, and other migratory and resident fish to enter the ecosystem. Although there are objections to the removal of these historical dams, as some communities consider the dam an inherent feature of their town, objections can be assuaged by the preservation of portions of the dam that do not interfere with the river system.

The Division of Ecological Restoration’s actions are an important change to Massachusetts’ environmental policy. Most of the environmental protection laws are focused on maintaining the status quo, and on protecting the water resources from impacts. Removing dams, however, has a proactive and positive impact on water resources by changing the river or stream. The process of permitting the dam removal still takes longer than it should. The Division of Ecological Restoration and other agencies have proposed changes to the state permitting process, allowing aquatic restoration projects like dam removal to go through a permitting process that is easier and more streamlined, which can reduce costs and shorten permitting timelines. This is needed so that dams are removed before they become a hazard to the surrounding area. A faster permitting process will also help dam owners who cannot afford to maintain their dam for an indeterminate amount of time.

Dams have been an integral part of America’s history, however, the time has come to end the era of dam construction. Dams do not have an eternal lifespan, and often no longer serve the purposes for which they were originally built. The costs of maintaining degraded dams often exceed those of removing the dam and restoring the river system. The benefits of dam removal go beyond just the immediate area of the dam, and removing a dam, when planned in conjunction with removing or updating other dams on the river system, can help bring river ecosystems back to life. Massachusetts’ legislature began the process with the Act Furthering Dam Safety, Repair, and Removal, and should continue to fund the grants for removing dams around the state.

Rachel Watsky graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice environmental law.

Rachel Watsky graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice environmental law.

Drive-By Legislation Will Not Solve Drive-By Lawsuits

If you ask disability rights activists about the ADA Education and Reform Act of 2017 (the “Reform Act”), you may get a response that the Reform Act, which recently passed the House, is not nearly as benign or as amicable to the interests of persons with disabilities as its title suggests. In fact, many activists claim that the Reform Act would be downright harmful to persons with disabilities.

Tension over the Reform Act arises over key provisions requiring individuals with disabilities to give notice to businesses before filing a noncompliance lawsuit under the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). Currently, an individual can bring a lawsuit under Title III of the ADA immediately for a business’ failure to comply with the ADA. Under the proposed law, after receiving notice, the business would have 60 days to provide a written plan describing how the business will conform to the ADA’s requirements. The business then could take another 120 days to remove or make “substantial progress” toward removing the accessibility barrier. Individuals with disabilities would have to wait at least 180 days, if not longer, to enforce their civil rights under the ADA.

Although disability rights activists and many supporters of the disabled community oppose the proposed law, the Reform Act has some bipartisan support in Congress in an effort to stem the tide of excessive “drive-by” lawsuits.

Do we have a “Drive By” Lawsuit Problem in the United States?

“Drive-by” lawsuits are a practice where unscrupulous attorneys file hundreds of lawsuits alleging often minor, technical violations of the ADA. Lawyers working with as little as one plaintiff file lawsuits with boilerplate complaints looking for quick settlement payouts. These lawyers have often only visited the business they are suing one time and sometimes neither the lawyers nor their clients are patrons of the business.

Recent, more extreme versions of “drive-by” lawsuits are called “Google lawsuits;” where lawyers file lawsuits just by looking for ADA violations on Google Earth. By some estimates, businesses pay an average of $16,000 to settle these lawsuits rather than paying significantly more in legal fees to challenge the lawsuits in court. Under Title III of the ADA, a plaintiff cannot recover damages, but can recover attorneys’ fees along with injunctive relief (see p.378). Proponents of the Reform Act argue that these remedies promote excessive litigation.

Unfortunately, these “drive-by” lawsuits often do not result in increased ADA compliance. These settlements are often just shakedowns for cash, which may not actually lead to fixing the underlying ADA violation. As a result, some in the disabled community feel that these “drive-by” lawsuits actually harm relations between businesses and persons with disabilities. Still, could the Reform Act do more harm than good?

Could the ADA Education and Reform Act Damage the ADA?

Originally enacted in 1990, the ADA has improved the lives of countless individuals with disabilities. The ADA passed with widespread bipartisan support and is considered one of the most comprehensive and progressive disability civil rights statutes in the world. In fact, many other nations have modeled their disability rights laws after the ADA.

The ADA is effective, in part, because of two key areas: Title I and Title III, which allow private rights of action to enforce individual rights. Title I protects persons with disabilities in the employment context, and Title III protects persons in public accommodations. Under Title III, places of public accommodation must remove accessibility barriers, but only if this is “readily achievable” and not and where removing barriers would require a fundamental alteration or an undue burden. Unfortunately, although employers and places of public accommodation must proactively comply with the ADA, persons with disabilities often have to bring lawsuits to enforce the provisions of the ADA. Businesses comply with the ADA not only because it is the right thing to do, but also because of the threat of lawsuits.

Accordingly, disability rights activists decry the Reform Act as a thinly veiled threat to disability rights. The proposed law would fundamentally shift the balance of power for ensuring compliance to favor businesses. Instead of proactive compliance, businesses could sit on their hands and wait to be sued. Then, businesses would only have to show “substantial progress” toward compliance, not even full compliance, over the course of months. For those who are legitimate patrons of a business and who require accessibility, waiting six months or more for “substantial compliance” is simply not a realistic option.

A Path Forward: Changing Our Perception

Disability rights attorney Robyn Powell argues changes can be made without the Reform Act. First, Ms. Powell posits that attorneys are bound not to represent individuals in frivolous lawsuits; making this is an issue for state courts and bar associations to address, not Congress. Second, Ms. Powell points out that the, “ADA does not require any action that would cause an ‘undue burden’ or that is not ‘readily achievable,’” for a business to accomplish.

Many of the issues that the Reform Act seeks to address are issues that can be resolved without curtailing the civil rights of persons with disabilities. Both the business community and the disability community have mutual interests in ensuring that frivolous, “drive-by” lawsuits are prevented. However, rather than place severe restrictions on the rights of persons with disabilities through an extensive period of notice and opportunity to cure, other options should be considered.

States and their respective state bar associations could opt to impose stricter penalties for attorneys filing frivolous lawsuits under the ADA. Coupled with these stricter penalties, state bar associations could also adopt mechanisms like thresholds for the number of lawsuits that can be filed with one plaintiff under the ADA before an investigation is triggered. Alternatively, we could adopt requirements that prioritize injunctive relief over attorney’s fees or damages. Such requirements would force parties to engage with each other and would reduce the number of businesses that can be subject to “drive-by” lawsuits. Further, injunctive relief under the ADA would be consistent with the goals of truly achieving accessibility. At the very least, if the Reform Act moves forward, it should be amended so that the notice and opportunity to cure period is significantly shorter in order to lessen the burden that would be shifted to persons with disabilities.

Finally, when it comes to accessibility we would all do well to remember that accessibility is a universal issue, not just a disability issue. For example, stairs are an accommodation to people who are capable of walking to move between floors. Despite the frustration of these “drive-by” lawsuits, the fact that these lawsuits exist serve as a reminder that we must continue the push for improving accessibility for all people. With increased accessibility, there will be less opportunity to take unfair advantage of laws like the ADA.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018. He plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018. He plans to practice in Portland Oregon.