Category: Legislation in Court

Evaluating Massachusetts’ Tax Lien Foreclosure Laws Post Tyler v. Hennepin County

Last term, in Tyler v. Hennepin County, the Supreme Court ruled Minnesota’s tax lien foreclosure scheme unconstitutional, in violation of both the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause. Minnesota is one of twelve states, in addition to the District of Columbia, with tax lien foreclosure statutes. Sometimes referred to as “tax and take seizures” or “home equity theft,” these laws differ significantly from a typical bank foreclosure proceeding in which a homeowner can only lose equity already owed as debt. By contrast, foreclosure under tax lien laws can result in a homeowner losing the entire value of their home—often a financial loss multitudes greater than what the homeowner actually owed. Massachusetts is among the states that permit this practice. In the wake of the Tyler ruling, whether the law can or should remain on the books is worth examining.

In Tyler, Geraldine Tyler owed $15,000 in property taxes, but when Hennepin County foreclosed on her home and sold it for $40,000, it was able to keep the $25,000 balance of her equity. As Chief Justice John Roberts said, writing for a unanimous court, “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more.”

Massachusetts’ tax lien foreclosure law, found in Chapter 60, was passed in 1996 amidst a statewide budget crisis. According to Dan Bosely, the former legislator who wrote the law, it seemed like a creative revenue generator at the time, a way to help communities recoup lost revenue when people were not paying their real estate taxes or water and sewer bills. But the practice has been widely criticized by consumer advocates, and according to professors and lawyers familiar with tax lien laws across the country, the industry targets those in distress, mostly elderly and poor homeowners. According to Joshua Polk, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation who has litigated three Massachusetts-based cases, “It’s a transfer of wealth from the poorest people to either government entities or extremely wealthy investors.” In 2018, Bosely himself expressed concern about the consequences of the legislation. From 2014 to 2021, Massachusetts residents subject to tax lien foreclosure lost 82% of their home equity, which amounted to an average loss of $172,000 per homeowner.

Under the current Massachusetts law, a municipality can take control of a property itself or sell the right to foreclose to a private buyer. In the past decade, one Boston based investment company, Tallage Inc., has purchased two thousand tax liens from thirty cities and towns. According to Tallage’s general counsel, the company is acting in the public good, helping recoup lost revenue needed to pay for public schools, police stations, and firefighters. In fact, cash-strapped cities such as Worcester, Lowell, New Bedford, Pittsfield, and Quincy use tax lien foreclosures more often, likely due to a dire need to fill city coffers. However, whether thrusting people into more acute financial precarity or homelessness might not also have collateral consequences for a city’s bottom line seems worth examining. Further, when these third-party intermediaries are involved, private investors such as Tallage, not the municipality and its taxpayers, reap the lion’s share of the financial payout.

Under the current Massachusetts law, a municipality can take control of a property itself or sell the right to foreclose to a private buyer. In the past decade, one Boston based investment company, Tallage Inc., has purchased two thousand tax liens from thirty cities and towns. According to Tallage’s general counsel, the company is acting in the public good, helping recoup lost revenue needed to pay for public schools, police stations, and firefighters. In fact, cash-strapped cities such as Worcester, Lowell, New Bedford, Pittsfield, and Quincy use tax lien foreclosures more often, likely due to a dire need to fill city coffers. However, whether thrusting people into more acute financial precarity or homelessness might not also have collateral consequences for a city’s bottom line seems worth examining. Further, when these third-party intermediaries are involved, private investors such as Tallage, not the municipality and its taxpayers, reap the lion’s share of the financial payout.

In the wake of the Tyler ruling, an editorial in the Boston Globe urged Massachusetts to use this moment to reform its tax foreclosure laws: “Protecting the rights of homeowners ought to be part of any future legislative housing package.” Whether Tyler by itself invalidates the Massachusetts law is a different question. Unlike in Minnesota, Massachusetts tax foreclosures often happen through intermediaries like Tallage, making the government’s role more attenuated and thus potentially less dubious as a constitutional matter. Further, all Massachusetts tax foreclosures go through a Land Court hearing, at which, per a 2016 ruling, an owner may request a judicial sale to retain their equity in the property. Whether this provides any extra measure of protection is questionable though, as many individuals facing foreclosure may be unaware of these rights and unable to obtain legal counsel. Regardless of whether these procedural differences actually afford homeowners any more substantive protections, they are enough—from Tallage’s perspective—to place Massachusetts’ law squarely outside the scope of Tyler’s ruling.

To others, Tyler provides a clear mandate to change Massachusetts’ current statutory scheme. During a hearing of the Joint Committee on Revenue in June 2023, First Assistant Attorney General Pat Moore called the Massachusetts law a “classic unconstitutional taking,” undistinguishable from the one the Supreme Court just struck down. A case winding its way through the Massachusetts courts—in which a Worcester woman stands to lose $250,000 over a $2,600 unpaid tax bill—may soon clarify whether the judiciary will permit the practice to continue throughout the commonwealth.

Even if the Massachusetts courts find the Chapter 60 provisions distinguishable from those at issue in Tyler, the practice is problematic and the legislature should take action. According to UMass law professor Ralph Clifford, municipalities collect an average of $50 for every $1 of delinquent real estate owed. Raising revenue off the backs of a state’s poorest and medically compromised citizens and depriving them of the equity they have built up over years, even if constitutional, is surely unsound policy.

In February, 2023 Rep. Jeffrey Roy (D-Franklin) and Rep. Tommy Vitolo (D-Brookline) introduced H. 2937, “An act relative to tax deeds and protecting equity for homeowners facing foreclosure.” This bill would bring the law surrounding tax lien foreclosures in line with that governing mortgage foreclosures: a municipality would still have license to sell a property burdened by unpaid tax debt, but additional money from the sale, beyond the debt owed, would be returned to the homeowner. Another bill, H.2907, filed by Rep. Tram Nguyen (D-Andover), addresses concerns surrounding notice. While towns are required to provide written notice to homeowners at risk of tax foreclosure, the requirement is minimal and, given contemporary realities of how information is consumed, inadequate. According to a legal aid lawyer familiar with these cases, “Maybe [the requirements] made sense 100 year ago when people got their information from going to town hall or the post office, or from a newspaper…but in the context of our world today, using those procedures is calculated not to give notice, but to hide it from people.” H.2907 would require notice be understandable to an unsophisticated consumer. Given that those affected by tax lien foreclosures are usually elderly, medically compromised, or without the resources to hire an attorney, such enhanced procedural safeguards seem prudent.

Massachusetts legislators have filed bills addressing these issues in the past. With Tyler shining a national spotlight on this issue, advocates are hopeful the moment is ripe for reform. The legislature should not wait for the courts to take action in the wake of Tyler. Regardless of whether the current scheme passes constitutional muster from the perspective of the judiciary, real policy concerns with the statutory scheme have been exposed. The legislature has itself deemed, per Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 93, § 46, that a practice need not be illegal to be an unfair and unreasonable manner of debt collection. Legislators should seize on this moment to act as independent constitutional actors and pass the aforementioned legislation. Further, any reform regarding these laws would be remiss not to provide remedial measures for those who have already suffered injury due to this predatory practice.

Edie Leghorn anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Edie Leghorn anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

The Idiosyncrasies of Imbler: Absolute Immunity for Prosecutors Makes Absolutely No Sense

Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson once observed that: “The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America.” But with great power does not necessarily come great responsibility. When prosecutors present fabricated evidence and false testimony, make false statements, suborn or coerce perjury, conspire with a judge to predetermine the outcome of a case, withhold exculpatory evidence in a death penalty case, destroy exculpatory evidence, deny a speedy trial, and even violate a citizen’s right to be free from involuntary servitude, courts have held prosecutors are absolutely immune from civil liability. This immunity originates from the 1976 Supreme Court decision of Imbler v. Pachtman. In that case, Richard Pachtman, a prosecutor, withheld evidence that confirmed the alibi of a defendant in a murder trial, Paul Imbler, resulting in Imbler’s wrongful conviction. Yet, the Supreme Court held that Pachtman had absolute immunity from Imbler’s civil suit. The Imbler Court found support for absolute prosecutorial immunity in the “common law,” “history,” and “public policy.” Yet nearly half a century after Imbler, neither the common law, history, nor sound public policy provide continued support for absolute prosecutorial immunity.

The Imbler Court argued it was “well settled” that absolute immunity for prosecutors was “the common law rule.” In support of this claim, the Court cited a handful of lower court cases the earliest of which was decided in 1933. But none of these cases referenced English common law. At common law, absolute prosecutorial immunity was impossible as there was no such thing as a public prosecutor. Rather, private parties “prosecuted criminal wrongs which they suffered.” The public prosecutor was a “historical latecomer” who “did not emerge” in England until the “the Office of Director of Public Prosecutions” was established in 1879.

Even after public prosecution began in the U.S., as Justice Scalia recognized in his 1997 concurrence in Kalina v. Fletcher, there was “no such thing as absolute prosecutorial immunity.” Rather, prosecutors could be sued for malicious prosecution. For example, in 1854, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that a prosecutor accused of lying did not have absolute immunity and could be prosecuted for “malicious” acts. The first U.S. court case granting prosecutors absolute immunity was handed down by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1896. That decision, which “became the clear majority rule” across the U.S. in the decades after it was decided, mistakenly concluded that the 1854 Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court verdict which allowed for prosecutors to be sued for lying had in fact established that prosecutors were entitled to absolute immunity. Consequently, as Justice Scalia pointed out, Imbler was premised upon “a common-law tradition” that “was not even a logical extrapolation from then-established immunities.” At English common law, there was no such thing as a public prosecutor and throughout all of U.S. history until well after Reconstruction, public prosecutors had “the equivalent of qualified immunity” making them liable to suit for malicious acts.

The Imbler Court also made a historical argument in favor of absolute immunity for prosecutors, claiming that the Reconstruction Congress did not intend for the 1871 Civil Rights Act to be read to mean what it plainly says that “every person” acting under color of law who violates a U.S. citizen’s constitutional rights is subject to suit. Rather, according to the Imbler majority, when the Reconstruction Congress referred to “every person” they did not mean to include prosecutors. The Court produced no evidence from the legislative history of the 1871 Act to support this conclusion. Given that no U.S. court had ever granted absolute immunity to a prosecutor until 1896, it is impossible that the Reconstruction Congress had this non-existent immunity in mind when they were legislating in 1871. Justices Thurgood Marshall, Blackmun, Brennan, Scalia, and Thomas have all since ridiculed Imbler’s revisionist history. Moreover, the 1871 Civil Rights Act was passed in part to remedy “Southern prosecutors’ aggressive abuse of the judicial process” to “thwart Reconstruction and the enforcement of federal civil rights laws.” In just one Southern state, over 3,000 Union soldiers were prosecuted. The Civil Rights Act exposed Southern prosecutors to civil liability to prevent federal officials from being subjected to malicious and baseless prosecutions “for arresting southern violators of the Civil Rights Acts.” The Imbler Court did not consider this history, refusing to construe the text of the Civil Rights Act “as stringently as it reads,” and instead implanting into the heart of the Civil Rights Act a rule of absolute immunity even though the Imbler Court acknowledged that the law “on its face, admits of no immunities.”

The Imbler Court also made a historical argument in favor of absolute immunity for prosecutors, claiming that the Reconstruction Congress did not intend for the 1871 Civil Rights Act to be read to mean what it plainly says that “every person” acting under color of law who violates a U.S. citizen’s constitutional rights is subject to suit. Rather, according to the Imbler majority, when the Reconstruction Congress referred to “every person” they did not mean to include prosecutors. The Court produced no evidence from the legislative history of the 1871 Act to support this conclusion. Given that no U.S. court had ever granted absolute immunity to a prosecutor until 1896, it is impossible that the Reconstruction Congress had this non-existent immunity in mind when they were legislating in 1871. Justices Thurgood Marshall, Blackmun, Brennan, Scalia, and Thomas have all since ridiculed Imbler’s revisionist history. Moreover, the 1871 Civil Rights Act was passed in part to remedy “Southern prosecutors’ aggressive abuse of the judicial process” to “thwart Reconstruction and the enforcement of federal civil rights laws.” In just one Southern state, over 3,000 Union soldiers were prosecuted. The Civil Rights Act exposed Southern prosecutors to civil liability to prevent federal officials from being subjected to malicious and baseless prosecutions “for arresting southern violators of the Civil Rights Acts.” The Imbler Court did not consider this history, refusing to construe the text of the Civil Rights Act “as stringently as it reads,” and instead implanting into the heart of the Civil Rights Act a rule of absolute immunity even though the Imbler Court acknowledged that the law “on its face, admits of no immunities.”

Imbler’s final justification for its ruling was a “public policy” argument that absolute immunity was necessary to protect “honest prosecutors” from being “constrained” in their actions by the prospect of civil liability. But absolute immunity unnecessarily defends deliberately dishonest prosecutors. The Imbler Court itself acknowledged that absolute immunity “does leave the genuinely wronged defendant without civil redress against a prosecutor whose malicious or dishonest action deprives him of liberty.”

The record of wrongful convictions in which prosecutorial misconduct played a decisive role since Imbler overwhelmingly confirms this unconscionable reality. Over 2,700 wrongful convictions have been recorded with prosecutors committing misconduct in 30% of those cases with the real total likely far exceeding that amount. The most recent national study of prosecutorial that took place over two decades ago found over 11,000 cases of prosecutorial misconduct with over 2,000 cases resulting in reduced sentences, dismissed charges, or reversed convictions. Wrongfully convicted people have spent tens of thousands of years in prison collectively for crimes they did not commit since Imbler and many guilty persons have remained free to commit more crimes. Worse still, prosecutorial misconduct was implicated in over 550 death penalty reversals or 5.6% of all death penalty cases. In federal wrongful conviction cases, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, prosecutors commit misconduct “more than twice as often as police” and “seven times as often as police” in federal white-collar cases. Yet, all prosecutors at the federal level and most at the state level receive more immunity from suit than police officers who receive qualified immunity. Providing qualified immunity to prosecutors, the type of immunity that all executive officials enjoyed when the Reconstruction Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871, would protect honest prosecutors from frivolous suits while at the same time allowing the wrongfully convicted to hold prosecutors accountable for clearly established violations of constitutional rights.

The basic public policy error of the absolute immunity of Imbler is that it shields from liability all deliberately dishonest acts committed by prosecutors. It is one thing to argue that honest mistakes made by prosecutors acting in good faith should be immune from suit, but the Imbler Court took this too far and provided absolute immunity from suit for intentional bad faith acts committed by prosecutors that violate constitutional rights. The Imbler majority argued that prosecutors would be accountable through other means such as criminal liability and professional discipline. But only one prosecutor has ever been jailed for misconduct for a period of just 10 days, far shorter than the nearly 25 years the person whom he helped wrongfully convict spent in prison. Only 4% of prosecutors whose conduct played a role in securing wrongful convictions have been disciplined. One study of over 200 Justice Department cases of prosecutorial misconduct found zero instances of misconduct by federal prosecutors that resulted in disbarment. The public policy results of Imbler’s rule of absolute immunity for prosecutors over the past five decades confirm the old axiom that “absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Absolute immunity is simply too much power for the most powerful people in the U.S. criminal justice system to possess.

Imbler’s reasoning is non-sensical and utterly antithetical to a government “of laws and not of men” in which no official is “so high that he is above the law.” Imbler should be overturned by the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court does not overturn Imbler, then, as Judge James C. Ho of the Fifth Circuit recently observed, Congress can abolish absolute immunity “anytime it wants to do so” by clarifying that the 1871 Civil Rights Act was never intended to idiosyncratically allow prosecutors to flout the rule of law with impunity.

William Bock is a visiting student at Boston University School of Law and anticipates graduating from the University of Michigan Law School in May 2024.

William Bock is a visiting student at Boston University School of Law and anticipates graduating from the University of Michigan Law School in May 2024.

Emergency Opportunity: Legislating Away Roe v. Wade During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

At the outset of the pandemic, many states banned “nonessential” medical procedures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and preserve PPE. However, several states took the opportunity to classify abortion as a “nonessential” procedure, making the surgery inaccessible. At the same time, the FDA deregulated the requirements for in-person prescription of many drugs, even opioids, but continued to heavily regulate medication related to abortion.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

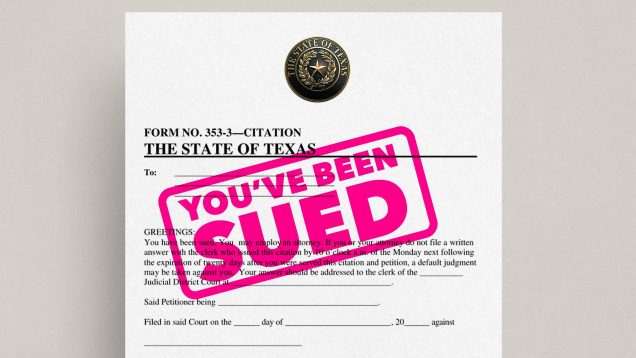

While the FDA was in legal battles over the requirements for medication abortion, conservative states began launching and defending legislation that restricted the right to a surgical abortion. During the 2021 session the Texas Legislature enacted the Texas Heartbeat Act, which bans abortion at the first sign of fetal heartbeat, which can be as early as 6 weeks. As BU Law and School of Public Health Professor Nicole Huberfeld pointed out, many women do not know they are pregnant within 6 weeks, and a “heartbeat” may mean no more than detecting an electrical pulse.

The key feature that has made Act a standout among anti-abortion bills is the citizen suit provision. The Act allows,

“any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local government entity in [the] state, may bring a civil action against any person who…performs or induces an abortion” or “aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.”

Enforcement is exclusively through private civil actions, a self-protecting mechanism that has been thought provoking for both the courts and the public. The lack of government enforcement leads many people to believe that there was no one to sue in order to challenge the legislation through judicial review. While the legislators may have thought this workaround clever, the Court recently held in Whole Women's Health v. Jackson that abortion providers may challenge the law by suing licensing officials. Still, the limited opportunity for judicial review may leave future constitutional rights vulnerable to this same evasive structure employed by the Texas legislation.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Just before announcing its limited decision allowing judicial review of the Heartbeat Act, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs centered around pre-pandemic Mississippi anti-abortion legislation, known as the “Gestational Age Act.” This Act directly confronts the holding of Planned Parenthood v. Casey by banning abortion after 15 weeks. It lacks the workaround that Texas employed but may nevertheless garner enough support from the Supreme Court to overturn the precedent from the Roe v. Wade line of cases. While Justice Roberts seemed inclined to uphold Roe but push back the line of imposing an undue burden to 15 weeks, other justices see the challenge as a call for an all-or nothing reversal of Roe. Overturning Roe would mean a complete change in the law surrounding abortion not just because of overturning common law precedent, but also because many states have drafted trigger laws, that specify that if Roe is overturned, abortion is automatically illegal in the state.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

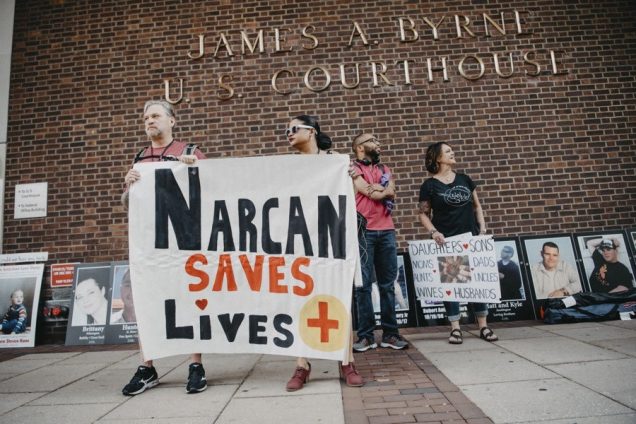

United States v. Safehouse: Could Philadelphia be the First State in the Nation to Implement a Supervised Drug Injection Site?

The opioid epidemic is one of the worst public health crises affecting the United States, and the rate of deaths resulting from opioid overdose has steadily increased. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a record high of more than 70,000 people died of a drug overdose in the United States in 2017, and over 47,000 of those deaths were from opioid overdoses. As lawmakers attempt to address this epidemic through public health initiatives , health advocates increasingly recommend using supervised injection sites to curb overdose deaths. Though legal barriers to this in the US exist, a recent District Court ruling in United States v. Safehouse may have paved the way for implementation of the first site of this kind in the US.

Injection sites provide a space where those using intravenous drugs can inject under the supervision of a medical professional ready to intervene in the event of an overdose, instead of unsupervised use where an overdose is more likely to be deadly. Supervised injection sites, also called safe injection facilities or safe consumption spaces, are a tertiary preventative public health measure aimed at combating overdose deaths and decreasing public use. In these spaces, injection drug users can self-administer drugs they bring to the facility in a controlled, sanitary environment under medical supervision. The medical personnel on staff at the sites do not directly handle the drugs and are there purely to administer Naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, in case of an overdose.

Despite the growing global presence in Europe, Australia, and Canada, scientific support for safe injection sites, and the interest of several cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Seattle, and San Francisco it is not entirely certain they can be operated in the United States. The Controlled Substances Act § 856, which regulates the production, possession, and distribution of controlled substances, makes it a criminal offense to maintain a drug-involved premises. Most academics agree that this “Crack House” Statute forbids safe injection sites and the courts can not definitively decide if safe injection site violate federal law until one is operational.

However, recently these assumptions have been called into question. Safe injection site proponents in many states have been appealing to legislatures and public health officials for funding. This effort has been largely unsuccessful due to political opposition and the looming threat of a federal lawsuit. In Philadelphia, which has the highest overdose rate of any major US city, a poll found roughly half of Philadelphians support a proposed safe injection site. Safehouse is a Philadelphia nonprofit that seeks to build the first safe injection site in the nation. In January 2018, Philadelphia health officials gave Safehouse permission to move forward with only private funds—preventing the need for legislative backing and appropriations.

In February 2019, federal prosecutors launched a civil lawsuit asking the U.S. District Court to rule on the legality of the Safehouse supervised consumption site plan, rather than waiting for the site to be built and then bringing federal criminal charges. U.S. Attorney William McSwain, working with Pennsylvania-based prosecutors, is seeking a declaratory judgment that medically supervised consumption sites per se violate 21 U.S.C § 856(a)(2)— the federal “Crack House” statute.

In February 2020, the court issued United States v. Safehouse, ruling that Safehouse’s plan to build a site where people could bring previously obtained drugs and use them under medical supervision for the purpose of combating fatal overdoses does not violate the Controlled Substances Act. Judge McHugh, looking at Congressional intent, ruled that §856 “does not prohibit Safehouse’s proposed medically supervised consumption rooms because Safehouse does not plan to operate them 'for the purpose of’ unlawful drug use within the meaning of the statute.” McHugh determines that at the time of enacting §856(a), Congress was focused on crack houses, not supervised drug injection sites. Even when amended in 2003, the focus was on “drug-fueled raves.” McHugh found that Congress neither expressly prohibited or authorized injection sites, so if §856(a) did not implicitly prohibit a consumption site, then implicit authorization naturally followed.

The question that the court addresses is whether the statute requires the defendant to know that third parties would enter their premises to consume illicit drugs, or rather that the defendant knowingly held their premises open for the purpose of facilitating illicit drug consumption. Judge McHugh concludes that the actor must “have acted for the proscribed purpose” to violate the statute. Therefore, the accused under a §856(a)(2) violation must have the purpose of facilitating illegal controlled substance use in the maintenance of a property.

Safehouse is planning “to make a place available for the purposes of reducing the harm of drug use, administering medical care, encouraging drug treatment, and connecting participants with social services.” The district court reasons that because of this, it could not conclude that Safehouse has, as a significant purpose, “the objective of facilitating drug use.”

In the wake of the ruling, U.S. Attorney McSwain announced that “this case is obviously far from over” and it is likely that the federal government will continue to litigate it. It is not unlikely that the Court that may hear this case on appeal disagrees with the District Court’s construction and strikes the legality of a supervised injection site based not on the intent of the person who controls the space, but the intent of the attendee of the site to use illicit drugs at that site, which has been the prevailing opinion up until the point of this ruling.

While the Safehouse case stands for an unexpected legal victory by way of the possibility of a supervised injection site to be opened in the United States, Philadelphia itself may not be the first state in the nation to implement one. The public sentiment in the wake of the decision was largely negative, with the local community being virulently opposed to the idea of a site being opened in the neighborhood from fear of what dangerous circumstances a site might attract. Plans to open the Safehouse site were put on indefinite hold. While proponents of Safehouse won the legal battle, winning over the community seems to be more of uphill battle than anticipated.

At this point in time, the legal position of supervised injection sites in the United States is tentatively positive. States who are looking to introduce this harm reduction initiative, and to be the first in the nation to do so, should take the opportunity to garner support from legislatures and local health care communities. While Philadelphia’s progression seems to be stymied, the District Court’s ruling provides significant legal precedent to ground encouragement for sites to be lobbied for in other states or cities that might not face the same type of community rejection that has prevented the opening of Safehouse.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Is the Johnson Amendment Constitutional?

My previous Dome blog entry discussed the Johnson Amendment and the fight that has surrounded the amendment since its creation in the 1950s. The Johnson Amendment was added to Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. tax code by then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson to limit the political activity of 501(c)(3) organizations. The Amendment prohibits 501(c)(3) organizations from endorsing or opposing political candidates. Many organizations have been trying to repeal the Johnson Amendment for years, and many argue (including members of Congress) that it violates the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Two vocal opponents of the Johnson Amendment (and the sponsors of the Free Speech Fairness Act in both houses of Congress) Senator James Lankford and Congressman Steve Scalise argue that the Amendment must be repealed to protect the First Amendment rights of 501(c)(3) non-profit employees. They argue the Bill of Rights protects the right of all Americans to freely express their ideas and opinions without persecution from the government, and the Johnson Amendment violates this right by stripping 501(c)(3) employees from being able to speak their minds about political issues. As discussed in my previous post, the Johnson Amendment prohibits 501(c)(3) employees from endorsing or opposing candidates, and violations of the Amendment risks punishment by the IRS either by fine, revocation of the organization’s tax-exempt status, or both. This, therefore, begs the question of whether the Johnson Amendment does in fact violate the First Amendment. This Dome blog post will look at legal precedent to see if the Amendment has been challenged for its constitutionality in the past, and if so, the arguments the court made in their decision.

Before going into court cases about whether or not the Johnson Amendment actually violates the First Amendment, it is important to look at the text itself. The text of the First Amendment reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Members of Congress and other organizations who oppose the Johnson Amendment mainly argue that it violates the freedom of speech, which is in fact why the current bill before Congress attempting to repeal the Amendment is titled the “Free Speech Fairness Act.” Within the text of the First Amendment, they argue that the Johnson Amendment is “abridging the freedom of speech” of 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit employees, but in particular religious ones, such as pastors, priests, and rabbis.

But has the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment actually been determined by the Supreme Court as it applies to religious organizations? The answer, unfortunately, is no. However, two U.S. Court of Appeals circuits have upheld the Amendment as constitutional in the past when applied to religious organizations. The first case, Christian Echoes Nat'l Ministry v. United States (1972), involved a nonprofit religious corporation contesting the revocation of its 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status by the IRS as punishment for violating the Johnson Amendment. Through various appeals and remands, the ultimate holding by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals was that the organization no longer qualified as a tax exempt organization under section 501(c)(3) of the tax code. As one argument against the revocation of their status, Christian Echoes argued the Johnson Amendment was unconstitutional and violated their right to free speech. However, the court held that “in light of the fact that tax exemption is a privilege, a matter of grace rather than right... the limitations contained in Section 501(c) (3) withholding exemption from nonprofit corporations do not deprive Christian Echoes of its constitutionally guaranteed right of free speech.” Christian Echoes Nat'l Ministry v. United States, 470 F.2d 849, 857 (10th Cir. 1972). The court therefore determined the taxpayer must refrain from these political activities to obtain “the privilege of exemption,” which Christian Echoes benefited from until their status was revoked.

The argument made by the court in Christian Echoes is very similar to the argument made by proponents of the Johnson Amendment, such as the Freedom From Religion Foundation, who argue because religious organizations benefit essentially from a government subsidy, in exchange for that subsidy they relinquish some of their rights. These rights can at any time be reclaimed, but at the cost of losing the subsidy, ultimately leaving the choice between the two up to individual organizations.

The District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals has also taken up this issue more recently in Branch Ministries v. Rossotti (2000), regarding the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment, but for violation of a different part of the First Amendment. In this case, a church had its tax-exempt status revoked for intervening in political campaigns, violating the Johnson Amendment. The church argued that revoking their tax-exempt status was a violation of the Free Exercise clause of the First Amendment, as in violating their right to freely exercise religion. To show the Free Exercise clause had been violated, the church had to establish their “free exercise right has been substantially burdened.” Branch Ministries v. Rossotti, 211 F.3d 137, 142 (2000). The court, however, held the Johnson Amendment did not violate the First Amendment because the church failed to establish that their free exercise right had been substantially burdened. Despite the claim by the church that by revoking their tax exempt status would threaten its very existence, the court determined this was overstated because the impact of revocation “is likely to be more symbolic than substantial,” because if they stop intervening in political campaigns they can regain their tax-exempt status, and even if they do not, “the revocation of the exemption does not convert bona fide donations into income taxable to the Church.” Therefore, the burden is not substantial enough to be considered a violation of the First Amendment. See, Branch Ministries, 211 F.3d at 142-143.

It seems currently that courts are finding the Johnson Amendment does not, in fact, violate the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has said in the past they believe tax benefits nonprofits are given are “a form of subsidy that is administered through the tax system,” which seems in line with the view of supporters of the Johnson Amendment and these two Court of Appeals cases. See, Regan v. Taxation with Representation, 461 U.S. 540, 544 (1983). They have not, however, delivered a decision on the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment as it applies to religious organizations. Therefore, despite the Court of Appeals cases, the fight over this issue is unlikely to end until the Supreme Court formally rules on the Johnson Amendment as it applies to religious organizations once and for all.

Kate Lipman anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Kate Lipman anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Mandatory Arbitration Clauses, Class Action Waivers, and the Need to Pass the FAIR Act

Mandatory arbitration clauses and class action waivers have become a fact of life for many American employees. A mandatory arbitration clause is contractual language that a company has a worker sign requiring that worker to resolve legal disputes in private arbitration — “a quasi-legal forum with no judge, no jury, and practically no government oversight”. A class action waiver is contractual language that a company has a worker sign that forfeits that employee’s right to file any claims collectively with other similarly situated workers. These provisions effectively strip away the rights of employees to challenge their employers in court with claims alleging wage and hour violations, discrimination, sexual harassment, and more. Congress must enact the FAIR Act so that our legal system vindicates employee rights to seek justice, access our courts, and end abusive employer practices.

Historically, it was commonplace for American courts to decline legal enforcement of arbitration agreements, especially adhesive contracts (Epic Sys. Corp. v. Lewis, 138 S. Ct. 1612 (2018)). When Congress passed the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) in 1925, legislative history suggests that the bill was intended to “enable merchants of roughly equal bargaining power to enter into binding agreements to arbitrate commercial disputes,” not to enforce mandatory arbitration agreements and class action waivers against workers in employment contracts. Members of Congress envisioned the FAA to provide an “opportunity to enforce…an agreement to arbitrate, when voluntarily placed in the document by the parties to it”; they did not intend to enforce the law in cases “where one party sets the terms of an agreement while the other is left [to] take it or leave it.” Until recently, courts upheld this interpretation of the FAA’s history and purpose (Prima Paint Corp. v. Flood & Conklin Mfg. Co., 388 U. S. 395 (1967))).

However, starting in the 1980s, this all changed. In Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp. (500 U. S. 20 (1991)), the Supreme Court held that the FAA requires mandatory arbitration agreements to be enforced against claims arising under the Age of Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA) antidiscrimination law. Later, in Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams (532 U. S. 105 (2001)), the Court held that the FAA’s §1 exemption for employment contracts involving “any...class of workers engaged in foreign or interstate commerce” should be construed narrowly to only apply to employment contracts involving transportation workers.

These landmark decisions spurred a widespread use of arbitration clauses in employment contracts, and emboldened employers to challenge state common law and statute protections that historically limited the enforceability of mandatory arbitration provisions and class action waivers. In 2011, the Supreme Court effectively overturned an earlier 2005 California Supreme Court case that had found legal protections for employees and consumers against the enforcement of class action waivers (AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333 (2011)). In Am. Express Co. v. Italian Colors Rest. (570 U. S. 228 (2013)), although Respondents argued that the arbitration and class action waiver provisions in their contract were unenforceable because they made effective vindication of their legal rights prohibitively expensive, the Supreme Court held that: 1) the FAA presumptively requires enforcement of contracts of adhesion; and 2) the “effective vindication rule” does not require that one’s assertion of rights be affordable or not cost-prohibitive, but rather only requires that one’s assertion of rights be not prohibited outright.

Eventually, the Supreme Court directly addressed the question of whether employment contracts that include mandatory arbitration provisions are enforceable in Epic Sys. Corp. v. Lewis. Employees argued that under the “saving clause” of the FAA, contractual language that violates the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) right to engage in “other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection” can be found unenforceable consistent with the FAA; this interpretation was adopted by the Ninth Circuit and consistent with NLRB precedent. However, the Supreme Court held that neither the “saving clause” nor the NLRA altered the legal requirement to enforce arbitration agreements prescribed by the FAA. The Court reasoned that state unconscionability defenses were not valid if they “interfer[ed] with fundamental attributes of arbitration,” such as individualized proceedings. Furthermore, the Court found that §7 of the NLRA did not guarantee employees the right to class or collective action procedures. Finally, the Court held that Chevron shouldn’t apply – based upon the NLRB’s 2012 decision – because: 1) the NLRB was interpreting the FAA, an act that the NLRB doesn’t administer; 2) the NLRB and the Solicitor General dispute the NLRA’s meaning and application; and 3) “there is no unresolved ambiguity for the Board to address.”

With arbitration clauses effectively privatizing our judicial system for many American workers, employees face information asymmetry and an imbalance of negotiating power with firms, and are therefore unable to contract under fair conditions. By implementing changes to our laws that prohibit employers from forcing employees to sign away their rights, society can improve both economic efficiency and equity within labor markets. Congress can do this by enacting the Force Arbitration Injustice Repeal (FAIR) Act. This Act, passed by the House of Representatives in September of 2019, would ban companies from requiring workers and consumers to resolve legal claims in private arbitration, and would invalidate current mandatory arbitration clauses and class action waivers that have already been signed in consumer or employee contracts.

With arbitration clauses effectively privatizing our judicial system for many American workers, employees face information asymmetry and an imbalance of negotiating power with firms, and are therefore unable to contract under fair conditions. By implementing changes to our laws that prohibit employers from forcing employees to sign away their rights, society can improve both economic efficiency and equity within labor markets. Congress can do this by enacting the Force Arbitration Injustice Repeal (FAIR) Act. This Act, passed by the House of Representatives in September of 2019, would ban companies from requiring workers and consumers to resolve legal claims in private arbitration, and would invalidate current mandatory arbitration clauses and class action waivers that have already been signed in consumer or employee contracts.

Passage of the FAIR Act would protect over 60 million American workers who have signed contracts with mandatory arbitration clauses and class action waivers. Marginalized communities (including women and communities of color), who are the most likely to be subjected to arbitration agreements because they constitute a huge share of the labor pool in industries like education, retail, and healthcare that use mandatory arbitration agreements and class action waivers the most, would greatly benefit from the FAIR Act by gaining access to the courts to litigate sexual harassment claims, sex discrimination claims, and racial discrimination claims. Furthermore, passing the FAIR Act would reduce the bias in employment disputes against employee interests, resulting from the conflict of interest between employers and arbitrators (employers pick the arbitration firm that will hear their case, pay the cost to hire the arbitrator or panel of arbitrators, and usually have a “cozy” relationship with the arbitrators they hire). Studies have found that, because of the “repeat player effect,” arbitrators are often biased toward employers who continuously pick them to handle their cases; Professor Amsler from Indiana University Bloomington demonstrated that “workers are nearly five times less likely to win their case if the arbitrator had handled past disputes involving her employer.”

The FAIR Act has been introduced by Senator Blumenthal in the Senate chamber, and has thirty-eight co-sponsors, but lacks any Republican co-sponsors and has failed to receive any congressional action since it was initially referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. While passage remains unlikely, it is incumbent on Congress to continue fighting for the FAIR Act. Given the Supreme Court’s conservative crusade to interpret the FAA in a way that guts workers’ rights over the last forty years, it is crucial that Congress pass this bill to promote economic, labor, humanitarian, and social justice for all Americans.

Samuel Shepard graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Samuel Shepard graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Raising the Blinds – Gaining Meaningful Insight into Pharmaceutical Pricing through Legislation

Rising healthcare costs are a growing concern across the United States; in 2016 U.S. health care spending was $10,348 per person – or 17.9 % of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). To counter this alarming rise in healthcare costs, states are addressing one of the largest factors in rising healthcare costs – high drug prices.

Many factors contribute to the high price of healthcare in our country, some of which are natural to an aging populace due to the baby boom of the 1950’s as the proportion of the population that is 65 and over is projected to experience a large increase in the coming years. An increase in costs is natural with a larger number of consumers – addressing this change is an important, but avoidable, challenge to overcome.

One avoidable factor of increasing healthcare costs is rapidly increasing pharmaceutical prices. Variance in drug prices may be geographic; based on where the drug is sold , or whom the drug is being sold to (pharmacy v. government). Many factors contribute to price differences, but an important factor are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) as an intermediate in the market. States have been working to roll back the PBM layer of the market for the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmaceutical pricing has long been the target of legislators, but with a lot of talk and a surprising lack of action. Drug pricing is discussed in both major party’s campaign platforms of the major parties and has been featured prominently in speeches by President Trump, and has featured in initiatives by previous administrations. There has been an uptick of legislation passed in the past decade, at all levels of government, with state action against pharmacy benefit managers and President Trump’s signing the Know the Lowest Price Act and the Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act. A common thread in the legislation is increased transparency because a big factor in the high drug prices — and medical care generally—is the lack of information for consumers and purchasers. Since 2015, California, Oregon, Louisiana, Nevada, Vermont, Connecticut, and Maryland imposed reporting requirements on pharmaceutical manufacturers who increase prices over an established threshold in a set time period. For example, California requires reporting when a drug that costs more than $40 and its wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) increases by more than 16% over two calendar years. The WAC is similar to a “list” price for pharmaceuticals to wholesalers and direct purchasers. The WAC, however, does not include discounts or rebates offered by pharmacy benefit managers.

The new transparency offers insight to price increases; if there are no legitimate reason for the increase other than higher profits due to market control, state officials, drug customers and the public can take action.

The states with transparency statutes have imposed different methodologies with manufacturers reporting to different government officials such as the Department of Health and Human Services, creation of new departments, or to the state’s Attorney General.

Oregon currently requires the most detailed reporting; manufacturers must report to the Department of Consumer and Business Services the following:

- Name, price of drug and net increase in price (in %) over previous calendar year

- Length of time on market

- Factors contributing to price increase

- Name(s) of any generic version(s) of the drug

- Research & Develop Costs from Public Funds

- Direct costs to Manufacturer

- Total sales revenue for drug over prev. calendar year

- Profit from drug over previous calendar year

- Drug's price at release and yearly increases over the past 5 years

- 10 highest prices paid for the drug during past year outside of the US

- Any other info relevant to price increase

- Supporting documentation

In contrast, California’s requirements provide for advance notice of price increases and unearthing the reasoning for the increase. The California law requires manufacturers to report (A) Date of increase, current WAC, and future increase in WAC (in dollar amounts); and (B) The change or improvement, if any, that necessitates the price increase. Purchasers then have notice of any forthcoming price changes and if the increase is warranted. California also requires a report for new drugs if its price exceed $670—the 2017 Medicare Part D threshold. California’s reporting scheme has been a model for other states.

Maryland’s approach was more severe, with a provision banning “price gouging” of generic drugs. An “unconscionable price increase” of any “essential off-patent or generic drug” is illegal and Maryland can levy a fine and take action to reverse the price change. The state did not include any limitation of the law to drugs that have come into or passed through Maryland.

The generic drug lobby, the Association for Accessible Medicines, challenged the law and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the law as an unconstitutional regulation of interstate commerce. Maryland has petitioned the Supreme Court to revisit the case.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers (PhRMA), one of the largest pharmaceutical lobbying groups, has sued California alleging the law, like Maryland’s, is unconstitutional. Because California’s law is informational—and does not allow forced price changes—it is likely constitutional. In fact, PhRMA’s initial complaint was dismissed, and subsequently filed an amended complaint on Sept. 18, 2018.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers (PhRMA), one of the largest pharmaceutical lobbying groups, has sued California alleging the law, like Maryland’s, is unconstitutional. Because California’s law is informational—and does not allow forced price changes—it is likely constitutional. In fact, PhRMA’s initial complaint was dismissed, and subsequently filed an amended complaint on Sept. 18, 2018.

It will be imperative for states seeking to regulate pharmaceutical manufacturers to observe where courts determine the extent of reporting they may require when they go after a manufacturer for increasing the price of their drug. For the time being, it appears that information-gathering may be the easiest available avenue for states seeking to curtail increases in drug prices. Seeking justifications and reasoning for large increases in drug prices may create a barrier for pharmacuetical companies seeking to impose unsubstantiated increases in drugs. Going further towards affirmative control of pricing appears to be off limits to states going as far as Maryland, but more careful structuring of the controls to the specific state may be permissible.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

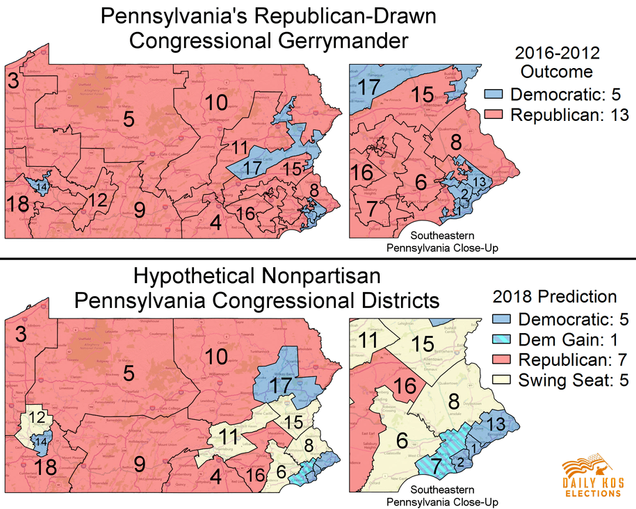

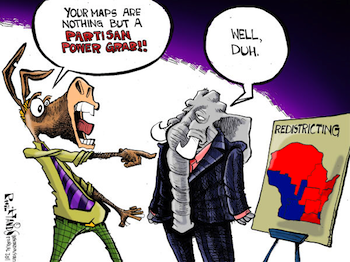

Can Partisan Gerrymandering be Stopped?

Attention to partisan gerrymandering has heightened as the next wave of redistricting fast approaches and the Supreme Court’s 2017-2018 docket included two cases regarding the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander. Following the release of the 2020 census, states will set out to redraw their district maps. States redistrict at least every ten years. The 2010 redistricting results are described as the most extreme partisan gerrymandering in our country’s history. The 2010 maps have a heavy Republican partisan advantage, as evidenced by the 2012 election results with Republicans gaining a 234 to 201 seat advantage in the House of Representatives despite Democrats winning 1.5 million more votes than Republicans. The Republican partisan advantage has remained strong. The Brennan Center for Justice has predicted that in the 2018 midterm elections Democrats will need to win by a margin of nearly 11 points to gain a majority in the House of Representatives. Democrats, however, have not won by a margin this large since 1974. Following years of heavily gerrymandered districts, a supermajority of Americans have indicated support for the Supreme Court to bring an end to partisan gerrymandering, yet the Court failed to take action this year.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering is the carving of districts, into sometimes odd shapes, to benefit a political party’s electoral prospects. The term gerrymandering was coined after Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts’s governor, in order to describe an irregularly shaped district that looked like a salamander in an 1812 redistricting map he signed into law. As a result, partisan gerrymandering has been a defining feature of “American politics since the early days of the Republic.” While racial gerrymandering is unconstitutional, the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering is an open question, as the Supreme Court has never struck down a map for partisan gerrymander.

Partisan gerrymandering seems to fly in the face of democracy. Voting is a fundamental right and electing who you want to represent you in office is a fundamental part of democracy. Legislatures that scheme, plan, and manipulate maps to benefit one party over another can undermine the purpose of democracy. Some of this scheming, planning, and manipulating is self-interested as legislatures try to protect incumbents and create safe districts, but can also serve the purpose of entrenching a political party’s majority until the next redistricting cycle. Both parties, Republicans and Democrats, have enjoyed the benefit of partisan gerrymandering when given the opportunity.

While the Supreme Court has indicated that some level of partisan gerrymandering may be unconstitutional, it has yet to explain when the constitutional line has been crossed. This term, the Supreme Court took up the question of partisan gerrymandering for the first time in more than a decade. The two cases before the Supreme Court were Gill v. Whitford and Benisek v. Lamone. The Supreme Court was asked to answer when partisan gerrymander crosses the constitutional line. Gill v. Whitford challenged a statewide map that has been deemed among one of the worst partisan gerrymandered maps in the country, with a significant Republican partisan advantage. Benisek v. Lamone challenged one congressional district in Maryland, with a significant Democratic partisan advantage. Some speculated that the Court took up both cases to deter an appearance that the Supreme Court prefers one party over the other. Another reason may be that the Wisconsin case was a challenge to a statewide map compared to the Maryland case challenging one congressional district.

The appellants attorney in Gill v. Whitford argued during oral arguments (see, page 62) that the Supreme Court is the only institution to put an end to partisan gerrymandering. The Court, however, sidestepped the entire issue by unanimously finding the Gill plaintiffs did not have standing, and that the challengers in Benisek had waited too long to seek an injunction blocking the district. The Supreme Court’s silence allows legislatures to continue to strategically gerrymander.

While the country waits on the Supreme Court to provide an answer on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymander, some states have attempted to take partisanship out of the process by using redistricting commissions, while others suggest that computers with algorithms should produce the maps. Yet, neither of these options individually seem to completely insulate redistricting from politics.

States have adopted redistricting commissions with the intention to remove partisanship from the redistricting process. However, this has often proved difficult to achieve, as finding non-partisan committee members is difficult and oftentimes the commission is appointed by partisan members, such as elected representatives and governors. States use different types of commissions and may only use a commission for redistricting the state map or congressional map. About 23 states use commissions for the state legislative maps and about 14 states use commissions for the congressional maps. The redistricting commissions can take the form of an advisory commission that makes suggestions to the legislature, a backup commission that draws the map if the legislature fails to redistrict, or as having the primary responsibility of drawing the map.

Even states that use independent redistricting commissions have had difficulties completely insulating the process from politics. For instance, in 2011, Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission chairwoman was removed by the Republican Governor and the Republican-controlled State Senate. The Governor accused the chairwoman of skewing the process for Democrats. The Arizona Supreme Court, however, reinstated the chairwoman and the United States Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s independent redistricting commission as a legitimate way to draw district maps. Although some states are moving toward redistricting commissions as a way to insulate the process from politics, these commissions are “only as independent as those who appoint it.”

While technological advances have been thought to help parties gerrymander more effectively, some suggest that similar technology could take politics out of the process with the proper algorithms. Brian Olson, a Massachusetts software engineer, wrote an algorithm to create “‘optimally compact’ equal-population congressional districts.” Olson prioritized the compactness requirement in an effort to reflect “actual neighborhoods” and because dramatically non-compact districts can be a “telltale sign of gerrymandering.” However, political scientists are skeptical about an algorithm prioritizing compactness, because it ignores other important factors, such as community of interest. Furthermore, someone needs to set the algorithm and there can be infinite map results. Thus, without very strict restrictions and guidelines, setting an algorithm and picking the map can still be an inherent gerrymander.

Removing politics completely from the redistricting process appears to be nearly impossible. Partisanship is deeply entrenched in the process, and dates back to even before the coined term “gerrymander.” Redistricting commissions do not always guarantee a partisan free redistricting effort, and while technology offers an alternative to human map drawing, humans are still making the final decision. Some combination of these efforts may help to lessen the amount of politics used in the redistricting process or lessen the appearance of partisanship, but are unlikely to completely end partisan gerrymandering all together.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Drive-By Legislation Will Not Solve Drive-By Lawsuits

If you ask disability rights activists about the ADA Education and Reform Act of 2017 (the “Reform Act”), you may get a response that the Reform Act, which recently passed the House, is not nearly as benign or as amicable to the interests of persons with disabilities as its title suggests. In fact, many activists claim that the Reform Act would be downright harmful to persons with disabilities.

Tension over the Reform Act arises over key provisions requiring individuals with disabilities to give notice to businesses before filing a noncompliance lawsuit under the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). Currently, an individual can bring a lawsuit under Title III of the ADA immediately for a business’ failure to comply with the ADA. Under the proposed law, after receiving notice, the business would have 60 days to provide a written plan describing how the business will conform to the ADA’s requirements. The business then could take another 120 days to remove or make “substantial progress” toward removing the accessibility barrier. Individuals with disabilities would have to wait at least 180 days, if not longer, to enforce their civil rights under the ADA.

Although disability rights activists and many supporters of the disabled community oppose the proposed law, the Reform Act has some bipartisan support in Congress in an effort to stem the tide of excessive “drive-by” lawsuits.

Do we have a “Drive By” Lawsuit Problem in the United States?

“Drive-by” lawsuits are a practice where unscrupulous attorneys file hundreds of lawsuits alleging often minor, technical violations of the ADA. Lawyers working with as little as one plaintiff file lawsuits with boilerplate complaints looking for quick settlement payouts. These lawyers have often only visited the business they are suing one time and sometimes neither the lawyers nor their clients are patrons of the business.

Recent, more extreme versions of “drive-by” lawsuits are called “Google lawsuits;” where lawyers file lawsuits just by looking for ADA violations on Google Earth. By some estimates, businesses pay an average of $16,000 to settle these lawsuits rather than paying significantly more in legal fees to challenge the lawsuits in court. Under Title III of the ADA, a plaintiff cannot recover damages, but can recover attorneys’ fees along with injunctive relief (see p.378). Proponents of the Reform Act argue that these remedies promote excessive litigation.

Unfortunately, these “drive-by” lawsuits often do not result in increased ADA compliance. These settlements are often just shakedowns for cash, which may not actually lead to fixing the underlying ADA violation. As a result, some in the disabled community feel that these “drive-by” lawsuits actually harm relations between businesses and persons with disabilities. Still, could the Reform Act do more harm than good?

Could the ADA Education and Reform Act Damage the ADA?

Originally enacted in 1990, the ADA has improved the lives of countless individuals with disabilities. The ADA passed with widespread bipartisan support and is considered one of the most comprehensive and progressive disability civil rights statutes in the world. In fact, many other nations have modeled their disability rights laws after the ADA.

The ADA is effective, in part, because of two key areas: Title I and Title III, which allow private rights of action to enforce individual rights. Title I protects persons with disabilities in the employment context, and Title III protects persons in public accommodations. Under Title III, places of public accommodation must remove accessibility barriers, but only if this is “readily achievable” and not and where removing barriers would require a fundamental alteration or an undue burden. Unfortunately, although employers and places of public accommodation must proactively comply with the ADA, persons with disabilities often have to bring lawsuits to enforce the provisions of the ADA. Businesses comply with the ADA not only because it is the right thing to do, but also because of the threat of lawsuits.

Accordingly, disability rights activists decry the Reform Act as a thinly veiled threat to disability rights. The proposed law would fundamentally shift the balance of power for ensuring compliance to favor businesses. Instead of proactive compliance, businesses could sit on their hands and wait to be sued. Then, businesses would only have to show “substantial progress” toward compliance, not even full compliance, over the course of months. For those who are legitimate patrons of a business and who require accessibility, waiting six months or more for “substantial compliance” is simply not a realistic option.

A Path Forward: Changing Our Perception

Disability rights attorney Robyn Powell argues changes can be made without the Reform Act. First, Ms. Powell posits that attorneys are bound not to represent individuals in frivolous lawsuits; making this is an issue for state courts and bar associations to address, not Congress. Second, Ms. Powell points out that the, “ADA does not require any action that would cause an ‘undue burden’ or that is not ‘readily achievable,’” for a business to accomplish.

Many of the issues that the Reform Act seeks to address are issues that can be resolved without curtailing the civil rights of persons with disabilities. Both the business community and the disability community have mutual interests in ensuring that frivolous, “drive-by” lawsuits are prevented. However, rather than place severe restrictions on the rights of persons with disabilities through an extensive period of notice and opportunity to cure, other options should be considered.

States and their respective state bar associations could opt to impose stricter penalties for attorneys filing frivolous lawsuits under the ADA. Coupled with these stricter penalties, state bar associations could also adopt mechanisms like thresholds for the number of lawsuits that can be filed with one plaintiff under the ADA before an investigation is triggered. Alternatively, we could adopt requirements that prioritize injunctive relief over attorney’s fees or damages. Such requirements would force parties to engage with each other and would reduce the number of businesses that can be subject to “drive-by” lawsuits. Further, injunctive relief under the ADA would be consistent with the goals of truly achieving accessibility. At the very least, if the Reform Act moves forward, it should be amended so that the notice and opportunity to cure period is significantly shorter in order to lessen the burden that would be shifted to persons with disabilities.

Finally, when it comes to accessibility we would all do well to remember that accessibility is a universal issue, not just a disability issue. For example, stairs are an accommodation to people who are capable of walking to move between floors. Despite the frustration of these “drive-by” lawsuits, the fact that these lawsuits exist serve as a reminder that we must continue the push for improving accessibility for all people. With increased accessibility, there will be less opportunity to take unfair advantage of laws like the ADA.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018. He plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018. He plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

“Am I Free to Go?” – It Depends On Who You Ask

Typically, when criminal proceedings against a person in state or local custody have been settled, he or she is free to go. This can occur either after that the individual's charges have been dismissed, they have posted bail, or their jail sentence has been completed. Yet, for years there has been confusion among states whether exceptions to this process can be made for certain immigrants. The confusion focuses on whether or not state or local law enforcement officials have the authority to detain an immigrant based solely on a request, or detainer, from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In other words, is an immigrant free to go once the criminal proceedings have been settled, or do these ICE detainer requests carry some legal weight? The answer to that question changes depending on who you ask.

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts was recently confronted with this question and on July 24, 2017 it issued a ruling in Commonwealth v. Lunn limiting the ability for state and local law enforcement officials to assist with federal immigration enforcement. To help address the issue, the court proceeded to “look to the long-standing common law of the Commonwealth and to the statutes enacted by our Legislature.” Ultimately, the court concluded that “nothing in the statutes or common law of Massachusetts authorizes court officers to make a civil arrest in these circumstances.” It was this language that presumably opened the door to recent legislation that was filed by Governor Baker August 1, 2017.