Category: State Legislation

A Legal Tug-of-War between the Massachusetts State Auditor and the Legislature

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts finds itself at a constitutional crossroads as the legal tug-of-war unfolds between the State Auditor and the Legislature. In August 2023, the Massachusetts State Auditor, Diana DiZoglio, sent a letter to Attorney General Andrea Campbell stating she was conducting an audit of both the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives (the Legislature). This audit would include “budgetary, hiring, spending, and procurement information, information regarding active and pending legislation, the process for appointing committees, the adoption and suspension of legislative rules, and the policies and procedures of the Legislature.” However, Campbell responded that the auditor cannot unilaterally probe the Legislature without its consent. In this case, both Ronald Mariano, Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and Karen Spilka President of the Massachusetts Senate rejected DiZoglio’s audit. They reasoned that the financial documents of the legislature are made public and the other information DiZoglio is requesting violates the separation of powers. This conflict is not new but rather a historical tug-of-war between the branches of government and the delegation of powers. This debate requires a comprehensive analysis of statutory powers, historical positions, and constitutional considerations.

DiZoglio is asserting her power to conduct this audit under the State Auditor’s enabling statute, M.G.L. c. 11 § 12. Section 12 directs the State Auditor to audit “accounts, programs, activities and functions directly related to the aforementioned accounts of all departments, offices, commissions, institutions and activities of the commonwealth, including those of districts and authorities created by the general court and including those of the income tax division of the department of revenue.” The language that Campbell focused on was the meaning of “departments” and whether the Legislature was intended to be included in that term. Campbell scrutinized various cases and the texts of other statutes using this term concluding that “department” is more restricted than it appears. From a historical perspective, the term “department” appeared in the text of the statute in 1920 at the same time the Massachusetts’s general laws were enacted and when the Executive Branch was reorganized into “departments.” Upholding the precedent of her predecessors, Campbell adopted the view that “the word ‘department’ in statutes such as these should in general encompass only executive branch departments.”

DiZoglio is asserting her power to conduct this audit under the State Auditor’s enabling statute, M.G.L. c. 11 § 12. Section 12 directs the State Auditor to audit “accounts, programs, activities and functions directly related to the aforementioned accounts of all departments, offices, commissions, institutions and activities of the commonwealth, including those of districts and authorities created by the general court and including those of the income tax division of the department of revenue.” The language that Campbell focused on was the meaning of “departments” and whether the Legislature was intended to be included in that term. Campbell scrutinized various cases and the texts of other statutes using this term concluding that “department” is more restricted than it appears. From a historical perspective, the term “department” appeared in the text of the statute in 1920 at the same time the Massachusetts’s general laws were enacted and when the Executive Branch was reorganized into “departments.” Upholding the precedent of her predecessors, Campbell adopted the view that “the word ‘department’ in statutes such as these should in general encompass only executive branch departments.”

DiZoglio contends that the Auditor’s Office has a precedent for auditing the Legislature, citing historical reports conducted on various agencies. The Auditor’s Office originally was charged with collecting annual reports on various government agencies that was eventually transferred to the Office of the Comptroller when that office was created 1922. The pre-1923 reports provided a broad overview of the financial information specifically detailing how the Legislature could reduce its expenditures. Campbell pointed out that the information that the Auditor is currently requesting goes beyond the limited scope and the functions the Auditor currently possesses. The reports from 1923-1971 were once again narrowly construed to certain entities “under the purview of the Legislature,” but not the Legislature as whole as DiZoglio is attempting to do now. From 1972-1990, the Auditor conducted audits of three specific legislative entities and reporting on their expenditures, appropriations, and other miscellaneous income. In 1978, the Senate stopped complying with the Auditor’s audits after the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decided Westinghouse Broadcasting Co. v. Sergeant-at-Arms of General Court (Mass. 1978). In Westinghouse, the Court held that “the records generated by the Legislature could be made available to outsiders only at the discretion of the House and Senate leadership.” The Senate cited this holding to restrict the Auditor’s access to certain records. From 1990 until 2023, the Auditor conducted three narrow audits of legislative operations: addressing overpayments to a court officer in 1992, IT-related controls by the Sergeant-at-Arms in 2002, and Legislative Information Services in 2006. In contrast, the Auditor’s proposed broad audit will scrutinize core legislative powers rather than specific issues or entities.

The enforcement of orders for document production against the Legislature raises serious constitutional questions related to the separation of powers. These concerns were raised by former State Auditors, Suzanne Bump and A. Joseph DeNucci. If the Auditor moves forward with the audit, it would require the Superior Court to enforce those orders against the Legislature’s consent. As provided by the Massachusetts Constitution, the legislative branch has the authority to establish its own rules and proceedings. Thus, if the Judiciary enforced the audit against the Legislature, it would be interfering directly with the Legislature’s core functions. Although Attorney General Campbell did not go so far as to define the extent of the constitutional limitations, it did acknowledge the potential for such an issue to arise.

The enforcement of orders for document production against the Legislature raises serious constitutional questions related to the separation of powers. These concerns were raised by former State Auditors, Suzanne Bump and A. Joseph DeNucci. If the Auditor moves forward with the audit, it would require the Superior Court to enforce those orders against the Legislature’s consent. As provided by the Massachusetts Constitution, the legislative branch has the authority to establish its own rules and proceedings. Thus, if the Judiciary enforced the audit against the Legislature, it would be interfering directly with the Legislature’s core functions. Although Attorney General Campbell did not go so far as to define the extent of the constitutional limitations, it did acknowledge the potential for such an issue to arise.

The Attorney General’s Office holds firm that the Auditor’s current authority does not extend to auditing the Legislature without consent. In response, the Auditor sought to ask the public whether she has the authority to audit the legislature through a question on 2024 ballot. DiZoglio’s proposal received over 100,000 signatures and is on track to be included on the 2024 state-wide ballot. First, however, the Legislature reviews the proposal, with the Judiciary Committee holding a tense hearing in March 2024. DiZoglio testified,

“Our office provides a resource to this commonwealth. Contrary to the narrative that some legislators and their supporters have been spinning, [my] office is not the FBI. We do not go in and raid people’s offices. We do not have the ability to toss desks. Our staff conducts performance audits. Audits. The amount of opposition to audits from this body is deeply, deeply disturbing and concerning on so many levels.”

However, Jeremy Paul, a law professor at Northeastern University, testified that the courts may invalidate the new law if the voters approve it in November.

“I submit that the power to audit may well turn out to be the power to destroy. It’s one thing to push for greater transparency in legislative operations so that the public is given more information. It’s entirely another to give an elected official inside the elected branch discretion to decide which legislators can be called to account for what reasons and when.”

Thus, the saga continues, serving as a constant reminder of the delicate balance that needs to be struck within our democratic system between responsibility, transparency, and the preservation of constitutional principles.

Abigail Rooney West anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Abigail Rooney West anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Evaluating Massachusetts’ Tax Lien Foreclosure Laws Post Tyler v. Hennepin County

Last term, in Tyler v. Hennepin County, the Supreme Court ruled Minnesota’s tax lien foreclosure scheme unconstitutional, in violation of both the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause. Minnesota is one of twelve states, in addition to the District of Columbia, with tax lien foreclosure statutes. Sometimes referred to as “tax and take seizures” or “home equity theft,” these laws differ significantly from a typical bank foreclosure proceeding in which a homeowner can only lose equity already owed as debt. By contrast, foreclosure under tax lien laws can result in a homeowner losing the entire value of their home—often a financial loss multitudes greater than what the homeowner actually owed. Massachusetts is among the states that permit this practice. In the wake of the Tyler ruling, whether the law can or should remain on the books is worth examining.

In Tyler, Geraldine Tyler owed $15,000 in property taxes, but when Hennepin County foreclosed on her home and sold it for $40,000, it was able to keep the $25,000 balance of her equity. As Chief Justice John Roberts said, writing for a unanimous court, “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more.”

Massachusetts’ tax lien foreclosure law, found in Chapter 60, was passed in 1996 amidst a statewide budget crisis. According to Dan Bosely, the former legislator who wrote the law, it seemed like a creative revenue generator at the time, a way to help communities recoup lost revenue when people were not paying their real estate taxes or water and sewer bills. But the practice has been widely criticized by consumer advocates, and according to professors and lawyers familiar with tax lien laws across the country, the industry targets those in distress, mostly elderly and poor homeowners. According to Joshua Polk, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation who has litigated three Massachusetts-based cases, “It’s a transfer of wealth from the poorest people to either government entities or extremely wealthy investors.” In 2018, Bosely himself expressed concern about the consequences of the legislation. From 2014 to 2021, Massachusetts residents subject to tax lien foreclosure lost 82% of their home equity, which amounted to an average loss of $172,000 per homeowner.

Under the current Massachusetts law, a municipality can take control of a property itself or sell the right to foreclose to a private buyer. In the past decade, one Boston based investment company, Tallage Inc., has purchased two thousand tax liens from thirty cities and towns. According to Tallage’s general counsel, the company is acting in the public good, helping recoup lost revenue needed to pay for public schools, police stations, and firefighters. In fact, cash-strapped cities such as Worcester, Lowell, New Bedford, Pittsfield, and Quincy use tax lien foreclosures more often, likely due to a dire need to fill city coffers. However, whether thrusting people into more acute financial precarity or homelessness might not also have collateral consequences for a city’s bottom line seems worth examining. Further, when these third-party intermediaries are involved, private investors such as Tallage, not the municipality and its taxpayers, reap the lion’s share of the financial payout.

Under the current Massachusetts law, a municipality can take control of a property itself or sell the right to foreclose to a private buyer. In the past decade, one Boston based investment company, Tallage Inc., has purchased two thousand tax liens from thirty cities and towns. According to Tallage’s general counsel, the company is acting in the public good, helping recoup lost revenue needed to pay for public schools, police stations, and firefighters. In fact, cash-strapped cities such as Worcester, Lowell, New Bedford, Pittsfield, and Quincy use tax lien foreclosures more often, likely due to a dire need to fill city coffers. However, whether thrusting people into more acute financial precarity or homelessness might not also have collateral consequences for a city’s bottom line seems worth examining. Further, when these third-party intermediaries are involved, private investors such as Tallage, not the municipality and its taxpayers, reap the lion’s share of the financial payout.

In the wake of the Tyler ruling, an editorial in the Boston Globe urged Massachusetts to use this moment to reform its tax foreclosure laws: “Protecting the rights of homeowners ought to be part of any future legislative housing package.” Whether Tyler by itself invalidates the Massachusetts law is a different question. Unlike in Minnesota, Massachusetts tax foreclosures often happen through intermediaries like Tallage, making the government’s role more attenuated and thus potentially less dubious as a constitutional matter. Further, all Massachusetts tax foreclosures go through a Land Court hearing, at which, per a 2016 ruling, an owner may request a judicial sale to retain their equity in the property. Whether this provides any extra measure of protection is questionable though, as many individuals facing foreclosure may be unaware of these rights and unable to obtain legal counsel. Regardless of whether these procedural differences actually afford homeowners any more substantive protections, they are enough—from Tallage’s perspective—to place Massachusetts’ law squarely outside the scope of Tyler’s ruling.

To others, Tyler provides a clear mandate to change Massachusetts’ current statutory scheme. During a hearing of the Joint Committee on Revenue in June 2023, First Assistant Attorney General Pat Moore called the Massachusetts law a “classic unconstitutional taking,” undistinguishable from the one the Supreme Court just struck down. A case winding its way through the Massachusetts courts—in which a Worcester woman stands to lose $250,000 over a $2,600 unpaid tax bill—may soon clarify whether the judiciary will permit the practice to continue throughout the commonwealth.

Even if the Massachusetts courts find the Chapter 60 provisions distinguishable from those at issue in Tyler, the practice is problematic and the legislature should take action. According to UMass law professor Ralph Clifford, municipalities collect an average of $50 for every $1 of delinquent real estate owed. Raising revenue off the backs of a state’s poorest and medically compromised citizens and depriving them of the equity they have built up over years, even if constitutional, is surely unsound policy.

In February, 2023 Rep. Jeffrey Roy (D-Franklin) and Rep. Tommy Vitolo (D-Brookline) introduced H. 2937, “An act relative to tax deeds and protecting equity for homeowners facing foreclosure.” This bill would bring the law surrounding tax lien foreclosures in line with that governing mortgage foreclosures: a municipality would still have license to sell a property burdened by unpaid tax debt, but additional money from the sale, beyond the debt owed, would be returned to the homeowner. Another bill, H.2907, filed by Rep. Tram Nguyen (D-Andover), addresses concerns surrounding notice. While towns are required to provide written notice to homeowners at risk of tax foreclosure, the requirement is minimal and, given contemporary realities of how information is consumed, inadequate. According to a legal aid lawyer familiar with these cases, “Maybe [the requirements] made sense 100 year ago when people got their information from going to town hall or the post office, or from a newspaper…but in the context of our world today, using those procedures is calculated not to give notice, but to hide it from people.” H.2907 would require notice be understandable to an unsophisticated consumer. Given that those affected by tax lien foreclosures are usually elderly, medically compromised, or without the resources to hire an attorney, such enhanced procedural safeguards seem prudent.

Massachusetts legislators have filed bills addressing these issues in the past. With Tyler shining a national spotlight on this issue, advocates are hopeful the moment is ripe for reform. The legislature should not wait for the courts to take action in the wake of Tyler. Regardless of whether the current scheme passes constitutional muster from the perspective of the judiciary, real policy concerns with the statutory scheme have been exposed. The legislature has itself deemed, per Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 93, § 46, that a practice need not be illegal to be an unfair and unreasonable manner of debt collection. Legislators should seize on this moment to act as independent constitutional actors and pass the aforementioned legislation. Further, any reform regarding these laws would be remiss not to provide remedial measures for those who have already suffered injury due to this predatory practice.

Edie Leghorn anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Edie Leghorn anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Running Out of Room: The Right to Shelter in Massachusetts

On August 8, 2023, Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey declared a state of emergency because state resources were insufficient to comply with the Commonwealth's right to shelter law. Although the law has been in place for 40 years, a rapid increase in the number of people requesting shelter and the declaration of a state of emergency has inspired new debates and tensions around the right to shelter. To maintain the spirit of the law but not overburden the Commonwealth, compromises must be made to continue the legacy of the right to shelter.

Governor Dukakis & Right to Shelter

In 1983, Massachusetts closed its mental hospitals, which along with rising drug use, left people homeless and sleeping in the streets across the state. In response, Governor Michael Dukakis filed legislation guaranteeing shelter for every homeless family in the state. Ten months later he signed the ‘right to shelter’ law.

The emergency assistance program, colloquially known as the right to shelter law, is meant to protect children from homelessness if their parents fall onto hard times. The law guarantees shelter for families with children and pregnant people without children. Under the law, the state must quickly provide shelter and basic necessities to families who have nowhere else to stay.

Governor Healey & Current Crisis

On July 31, before the state of emergency, a group of Massachusetts legislators released a letter urging the federal government to streamline the process for work authorizations so immigrants can begin working and stop depending on the state. Employment authorization had a wait time of six months or longer, thus forcing immigrants to rely on the state as they cannot legally work without authorization.

On August 8, Governor Healey declared a state of emergency after months of rapid escalation of families seeking shelter. Along with the state of emergency, the state reported spending nearly $45 million per month on programs to help families eligible for emergency assistance. As of October 2023, nearly 7,000 families were in emergency shelter and about half of those in shelter were children. The governor said the state would be unable to accommodate new families by the end of October 2023. Despite the inflated numbers and costs, the governor made it very clear that the law was not ending, but Massachusetts needed federal assistance, sites to house people, staffing, and funds to continue doing the work of sheltering those in need.

Massachusetts is the only state that has a right to shelter. The most similar law is a New York City consent decree that guarantees all unhoused individuals—not just families—shelter within city limits. The city’s right to shelter law has also been facing criticism as an increase in unhoused people and an influx of immigrants has overburdened that system as well. In response to the surge of families seeking shelter, New York City Mayor Adams suspended some components of the law, Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state of emergency, and subsequently received $104.6 million federal funds in response. Much like what happened in New York City, Mayor Healey is attempting to solicit federal assistance to mitigate the rapid increase in those seeking shelter and the amount of state resources being allocated to handling the crisis.

Massachusetts is the only state that has a right to shelter. The most similar law is a New York City consent decree that guarantees all unhoused individuals—not just families—shelter within city limits. The city’s right to shelter law has also been facing criticism as an increase in unhoused people and an influx of immigrants has overburdened that system as well. In response to the surge of families seeking shelter, New York City Mayor Adams suspended some components of the law, Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state of emergency, and subsequently received $104.6 million federal funds in response. Much like what happened in New York City, Mayor Healey is attempting to solicit federal assistance to mitigate the rapid increase in those seeking shelter and the amount of state resources being allocated to handling the crisis.

Debates Over Right to Shelter

Since the beginning of 2023, there has been increased criticism of the right to shelter in Massachusetts. People claim the housing crisis paired with the surge of immigrants entering the state have overburdened the emergency assistance system. Further, they claim the right to shelter has turned Massachusetts into a ‘migrant magnet.’ Overall, critics see the right to shelter as an outdated relic that cannot keep up with current demands. These criticisms have come with calls for the law to be amended, suspended, or altogether repealed.

Rep. Peter Durant (R-Worcester), is among the most vocal in expressing criticisms of the right to shelter law. Durant firmly believes the right to shelter law is being overrun by migrant families asking for assistance and suggested adjusting the law to excluding immigrants from receiving aid under this law. On September 14, 2023, Durant proposed H.4561 (An Act Ensuring Fair Housing for Homeless Families) to amend the right to shelter law to only apply to U.S. citizens. He is joined by twelve other petitioners, and the bill is still in committee as of October 2023.

Despite the criticism, there is still sizable support for the law amidst the crisis. Sarang Sekavat, chief of staff at Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, testified, “The idea [of the law] has always been to help out families and really to make sure that children aren’t suffering when their parents fall on hard times, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing right now.” 76% of Massachusetts residents, especially immigration and housing advocates, agree with Sekavat and believe the law is operating exactly as it was meant to and exemplifies the character of Massachusetts.

Moving Forward

Although the current housing crisis is putting the right to shelter law under intense scrutiny, the law is functioning as intended. The law was passed with children in mind and with the goal of ensuring no child had to sleep on the streets of Massachusetts. There is a rising need for housing, influenced by the housing and immigration crises, and many children do not have housing. The law has been an important part of Massachusetts’ identity for four decades, and to repeal it now when people need it most would be to go against the very nature of the Commonwealth.

On the other hand, concessions may need to be made for the well-being of the Commonwealth. If the Commonwealth overextends itself and its resources to meet rising needs, it may jeopardize the longevity of the right to shelter and similar programs. In 1983 there was no way to predict the amount of people seeking shelter in 2023. Now, there is no way to predict the trends in people seeking shelter, particularly if it will continue to increase or when it will stop. If Massachusetts will run out of room imminently, difficult decisions must be made to address the need for shelter with the availability of resources and housing.

The path forward must be a mix of aspiration and reality. Massachusetts must solicit support from the federal government with financial assistance and an expedited process for work authorizations. Further, Massachusetts must look inward to equitably share the responsibility among all towns and cities, as well as plan to increase the housing available for those in need. Additionally, the Massachusetts Legislature could pass legislation to address the housing crisis, including implementing rent caps and moratoriums on evictions. To continue the legacy of the right to shelter law, the Massachusetts and federal governments must work together to address the current crisis and preserve the law for those who need it in the future.

Juliana Hubbard anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Juliana Hubbard anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Massachusetts Broker’s Fees: Reasonable Service or Market Manipulation?

In 2023 Massachusetts established the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities with an eye toward creating more housing in the state, which, like many across the country, is suffering a housing shortage. Some estimates suggest that Massachusetts will require between 125,000-200,000 additional housing units by the end of the decade. Various proposals are currently being considered as how to best spur the creation of new homes. The eventual solution will not be a single provision but likely many policy amalgams from various sectors. One proposal currently before the Joint Committee on Housing is Senator James B. Eldridge’s bill, An Act Enabling Local Options for Tenant Protections (Bill S. 872). One of the more quietly influential provisions in the bill, Section 8(g),[i] should be amended to be mandatory across the state, rather than allowing municipalities to opt into the provision and the language regarding should be changed to prohibit the business from charging tenants a fee. Any of the various similar bills that the committee is considering should adopt Section 8’s amended language.

Section 8(g) could alone reduce the cost of relocating to a new apartment by almost 20%, greatly increasing the mobility of Massachusetts tenants, and concomitantly, increasing the competitive demand for more, new housing units. The bill allows municipalities, to prohibit tenant-paid broker fees. Currently, tenants relocating in the Commonwealth may be required to provide first month’s rent, last month’s rent, a security deposit, and a broker’s fee at signing. Security deposits and broker’s fees are traditionally tied to the price of the housing unit and often are equivalent to one month’s rent. The median rental price for a one-bedroom apartment in Boston (certainly the state’s most expensive large housing market) is above $2,900, meaning that a renter must find $11,600 to move—likely before they’ve received their previous security deposit back.

The remainder of the bill provides for municipalities to adopt, should they so choose, rent stabilization regulations, standards for just cause eviction protection, condominium conversion ordinances, prohibitions on immediate rent increases in response to the bill, anti-gentrification displacement protections, and regulations of fees. Each provision has its merits and deserves its own full analysis not available in this article.

While the bill before the Housing Committee allows for different municipalities to adopt different policies, the state’s goal of new housing would be better served by prohibiting the practice of broker's fees. In the modern housing market, tenants are often looking for units through online platforms and only being connected with brokers after inquiring into specific properties. However, nothing prevents multiple brokers from presenting the same listing because landlords can provide their listing to multiple brokers. Under such a model prospective tenants must pay the vendors that their landlord contracted with, making renters captive consumers, which distorts natural market forces and contradicts the needs of the broader housing market and tenants’ interests.

Other cities and states have recently tried to put forward similar provisions to varying results. Often such proposals face significant pushback from broker-related interest groups. The housing market inefficiency is a case study in the challenge of making reforms in circumstances of concentrated interests and diffuse costs. While renters may feel aggrieved about their new apartment costs, they likely only face the additional expense no more frequently than once per year. Meanwhile, brokers reap substantial benefit from a captive market and thus have every incentive to ensure no progress or changes are made to their outdated role in a modern market. The housing shortage allows landlords to deflect the cost onto tenants because tenants have so little choice in the current shortage; thus, no competitive price pressure, by either landlords or tenants, are exerted on brokers to provide competitive fees or better services.

Broker groups have suggested that prohibitions on tenant-paid fees will increase rents by requiring landlords to cover the costs. They are likely correct; though it is likely of little consequence. Assuming that the one-month’s-rent broker fee is a competitively derived price for services rendered and assuming that brokers are actually required in modern apartment leasing (two generous assumptions): if a landlord is instead required to pay the $2,900 broker fee for a broker finding a tenant for a median one-bedroom Boston apartment, we could expect that they would raise the rent of the apartment by as much as $247.44 (spreading the $2,900 expense with 5% annualized interest over 12 monthly payments), an 8.5% increase. While an 8.5% increase in rent sounds substantial, (all assumptions holding constant) the tenant’s housing costs over the same first twelve months has increased only 0.002% while the cost of relocating has decreased by 18.6%. The substantial reduction in cost to relocate to a new apartment (which, albeit, doesn’t include moving expenses, i.e. boxes, truck rental, moving company, favors and pizzas for friends) increases tenants’ ability to more successfully exert their demand force as consumers, which requires the market to respond proportionately, through a reduction in rental costs or an increase in the quality or quantity of housing.

Broker groups have suggested that prohibitions on tenant-paid fees will increase rents by requiring landlords to cover the costs. They are likely correct; though it is likely of little consequence. Assuming that the one-month’s-rent broker fee is a competitively derived price for services rendered and assuming that brokers are actually required in modern apartment leasing (two generous assumptions): if a landlord is instead required to pay the $2,900 broker fee for a broker finding a tenant for a median one-bedroom Boston apartment, we could expect that they would raise the rent of the apartment by as much as $247.44 (spreading the $2,900 expense with 5% annualized interest over 12 monthly payments), an 8.5% increase. While an 8.5% increase in rent sounds substantial, (all assumptions holding constant) the tenant’s housing costs over the same first twelve months has increased only 0.002% while the cost of relocating has decreased by 18.6%. The substantial reduction in cost to relocate to a new apartment (which, albeit, doesn’t include moving expenses, i.e. boxes, truck rental, moving company, favors and pizzas for friends) increases tenants’ ability to more successfully exert their demand force as consumers, which requires the market to respond proportionately, through a reduction in rental costs or an increase in the quality or quantity of housing.

The flaw in such an analysis is the omission of any future years’ rents based off the initial absorption of the broker fee. That is to say, even assuming the rent does not get raised after one year, the tenants will be paying that additional $247.44 each month of every year after the first. So over two years the housing costs would increase by 4.2%. It is worth noting however, that the two listed assumptions are not the legal reality in a number of competing states. Accordingly, any such reactionary rise in rent prices is not a given, and certainly not an increase of 8.5% as discussed above. Additionally, such a calculus does not consider the prohibition on immediate rent increases elsewhere in Senator Eldridge’s bill. Nor does it account for other provisions not yet proposed. For instance, California does not allow landlords to request or accept last month’s rent, and the justification for continuing to require Massachusetts residents to makes increasingly little sense in the present shortage.

The current fee-shifting model onto tenants provides perverse and inefficient market incentives for the actors in the field. With inadequate housing stocks, landlords are able to defer screening and application costs onto brokers and are not incentivized to make applying more efficient for tenants. Nor is there substantial incentive to add to or improve the available housing stock. Brokers, because there are is no expectation of exclusivity, have no increasing marginal interest in providing additional efforts to find tenants as another broker may fill a vacancy before they can, especially as most tenants locate apartments through non-broker-affiliated online platforms in the modern market. Nor are brokers incentivized to provide competitive fees as the industry has agreed upon the equivalent of one month’s rent, the price-fixing characteristic central to the economic definition of a cartel.

Meanwhile, throughout the process, tenants have limited selection and face rental prices inflated by the squeeze of the housing shortage. Even tenants who don’t move are harried by the practice as sizable year over year rent increases are unavoidable because of the exclusionary capital required to move elsewhere. Currently, to avoid a rent increase and move requires having on-hand the equivalent of four month’s rent. Which is a cruel absurdity given that 44.5% of households in the Greater Boston area in 2022 were cost burdened according to the Boston Foundation’s Greater Boston Housing Report Card, that is spending more than 30% of their income on rent. The same report showed that nearly half of those cost burdened, 22.7% of households in the Greater Boston area, are severely cost burdened, spending more than 50% of their income on rent. To bind families in a Catch-22 that they cannot seek less expensive housing unless they save the equivalent of four months rent while they are currently paying more than half of their income towards their current rent leaves countless Massachusetts residents teetering at the edge of housing insecurity.

Any adjustment to the current fee scheme, let alone a blanket prohibition on the practice, will activate lobbying efforts from the Massachusetts Association of Realtors, whose End of Session Legal Update in 2022 noted that they “successfully blocked rent control, eviction moratoria, [and] broker fee shifting….” Accordingly, any successful legislation will need to mobilize tenant organizations and various community grassroots organizations to advocate on behalf of lowering relocation prices and diffusing the benefit.

Massachusetts’ housing shortage will require the efforts of policy makers, stakeholders, and community members. The one thing that we can be confident won’t solve the state’s housing shortcomings is not altering the forces that created the problem. The current fee scheme operates as a state-sanctioned cartel that makes relocating markedly more difficult and thus suppresses proper demand and supply influences, further distorting the housing market in the Commonwealth. While it is not a panacea, tenant-paid broker fees should be consigned to the curb with the rest of waste.

[i] “(g) In addition to the powers granted to a city or town in this section and notwithstanding section 87DDD½ of chapter 112, a city or town may by local charter provision, ordinance or by law regulate, limit or prohibit the business of finding dwelling accommodations for a fee.”

Michael St. Germain anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

Michael St. Germain anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2025.

The Push and Pull of Municipal Fossil Fuel Bans in Massachusetts

In 2019, Brookline, Massachusetts became the first municipality outside of California to ban fossil fuels in new construction. The move was part of a growing movement among cities and towns to ban fossil fuel infrastructure, such as hookups for oil or natural gas use, in newly constructed buildings. Fossil fuel bans of this nature typically aim to curb emissions from energy use in buildings, which in many municipalities is the leading source of emissions, through electrification. Electricity use in buildings produces less carbon emissions than burning oil and gas directly and those emissions will continue to decrease as more renewable resources are added to the electricity grid.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Meanwhile, in the time between when Brookline passed its first fossil fuel ban and when the Attorney General issued its decision about the legality of the second ban, dozens of other Massachusetts municipalities became interested in enacting fossil fuel bans of their own. Some of these municipalities submitted home rule petitions to the Massachusetts legislature, asking the legislature to grant their individual municipalities the authority to ban fossil fuel infrastructure on a case-by-case basis. State Representative Tami Gouveia and State Senator Jamie Eldridge of Acton also introduced a bill during the 2021–2022 session that would have granted every municipality in the commonwealth the power to adopt a requirement for all-electric construction without passing and submitting a home rule petition.

The result was a compromise: The legislature passed An Act Driving Clean Energy and Offshore Wind in August of 2022. The law, among other things, authorized a pilot program enabling up to ten cities and towns to adopt and amend ordinances or by-laws to require new building construction or major renovation projects to be fossil fuel-free. The Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER) was tasked with developing the pilot program and deciding which municipalities would participate. Among requirements for cities and towns seeking to join the pilot program for fossil fuel bans is having a minimum of ten percent affordable housing.

DOER has already received more than ten applications from Massachusetts cities and towns wishing to join the pilot program, but under the draft regulations DOER published in February of this year, municipalities would have to wait until early 2024 at the earliest to implement their bans. This long period for implementation has disturbed members of the legislature who championed and passed the pilot program into law. Senator Michael Barrett, the Senate Chair of the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy recently told GBH News that the proposal would “delay the entire process much longer than the Legislature ever imagined.” Pressure from both the legislature and the municipalities seeking to join the pilot program will likely continue to mount as the group of cities and towns now includes the City of Boston, the largest city in the commonwealth. With advocacy groups concerned that the delay combined with limiting the pilot program to ten municipalities will hold the commonwealth back from meeting its goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050, legislators may be reconsidering the more conservative approach they took by passing the pilot program rather than blanket approval for cities and towns to enact fossil fuel bans.

Opponents and those concerned about the impacts of fossil fuel bans, however, may be heartened by the delay. Governor Charlie Baker considered vetoing the energy bill because of the fossil fuel ban pilot program because of the possibility that banning fossil fuels in new construction might make it more difficult to build affordable housing. In a state experiencing what many characterize as an affordable housing crisis, this concern is not uncommon, the thought process being that if there is inconsistency in requirements for developers between municipalities, developers, especially developers of affordable housing, will prioritize projects in communities with fewer or less expensive requirements. Many of the cities and towns that have already stepped forward to join the pilot program are fairly wealthy and may not be as concerned with the affect of a fossil fuel ban on the costs of housing development.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

The future of fossil fuel-free building in Massachusetts is uncertain. The legislature may choose to take a more aggressive approach than it did during the last session, or it may wait to see how DOER’s implementation of the pilot program goes, leaving Massachusetts cities and towns and developers to continue to innovate on their own. States are often called “laboratories of democracy,” but when it comes to issues like climate change, where municipalities acting individually may be able to make a large impact, that label may better suit cities and towns as they try again and again to form creative solutions where their state legislatures fall short.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

End the Request: It’s Time for Boston’s Biggest Landowners to Pay Their Fair Share

For the second time, Massachusetts State Representative Erika Uyterhoeven (D-Somerville) filed a bill concerning payments in lieu of taxes to cities and towns. This bill would strengthen and codify a Boston program, which requests payment from certain institutions that do not pay property taxes. It is important that this bill passes during the 2023-24 session because, without it, Boston (and other municipalities) will continue to subsidize large, private organizations at the expense of its own residents.

The City of Boston’s budget

The City of Boston’s operating budget consists of revenue from property taxes, state aid, local revenue, and, to a small extent, non-recurring revenue (e.g., funds from the American Rescue Plan Act). This revenue is used to fund programs and services, including public education, public safety, city departments, and transportation. Property taxes are consistently the City’s largest source of revenue, and its share size continues to increase as state aid decreases. For example, 74% of the City’s revenue is derived from property taxes this year compared to 52% in 2002.

Boston residential taxpayers currently pay $10.74 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge taxpayers spend $5.86; Somerville taxpayers spend $10.34 and Medford taxpayers spend $8.65. Boston commercial taxpayers, including small businesses pay $24.68 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is also higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge commercial tax payers spend $11.23, Somerville commercial taxpayers spend $17.35, and Medford commercial taxpayers spend $16.56.

Part of the reason why Boston’s property taxes are so high is that Boston’s tax base is constrained. Boston’s geographic region is relatively small and is home to many tax-exempt institutions.

52% of Boston’s area is tax exempt.

Tax-exempt areas include public land owned by the city, state, and federal government along with private land owned by universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions. These institutions are not required to pay property taxes as nonprofit charitable organizations under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. In Boston, this includes large, private institutions––like Mass General Brigham, Harvard, Boston University, and Northeastern––that together own over $14 billion of Boston’s real estate.

These large institutions do make some financial contributions to the city of Boston via the Payment in Lieu of Tax (“PILOT”) program. The PILOT program asks educational, medical, and cultural institutions with more than $15 million worth of tax-exempt property to make voluntary payments to the City of Boston. These contributions are supposed to be 25% of the would-be property taxes, and up to 50% of this payment can be in the form of “community benefits.” The 25% represents a “fair share” because large institutions’ use of essential services, such as fire safety, roads, public transportation, and sewage disposal generally make up 25% of a municipality’s budget.

The PILOT task force defines Community benefits “as services that directly benefit City of Boston residents; support the City’s mission and priorities with the idea in mind that the City would support such an initiative in its budget if the institution did not provide it; emphasize ways in which the City and the institution can collaborate to address shared goals; and, are quantifiable.” For example, these services can take the form of individual scholarships and job training initiatives. Other examples include summer camp and after school activities, preventative medical care, and maintenance of public spaces.

PILOT does not go far enough

Institutions often do not fulfill their PILOT requests from the City of Boston. During the 2022 fiscal year, Northeastern met 67% of its PILOT request. Boston University and Harvard did better, meeting 80% and 79% of their PILOT requests, respectively. However, these institutions tend to max out their community benefits. For example, during the 2022 fiscal year, the City of Boston requested $66,709,087 from educational institutions and received $30,793,921 in community benefits and only $14,788,450 in cash contributions. Here, it is worth emphasizing that $66,709,087 is only one quarter of what these institutions would pay if their properties were not tax-exempt.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Boston should be able to increase the amount of money generated from the city’s PILOT program to alleviate the pressure on its residents and small business owners and to ensure that large institutions pay their fair share for essential services. Changing these institutions from 501(c)(3) status to require payment of property taxes is likely a political and bureaucratic nightmare, especially given these institutions’ reliance on the nonprofit status. That said, some Massachusetts legislators are taking steps to ensure that universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions start to pay their fair share.

Bill H.2963

Representative Erika Uyterhoeven refiled Bill H.2963, An Act Relative to Payments In Lieu of Taxation by Organizations Exempt from the Property Tax on January 19 this year. The proposed bill:

- allows cities or towns to charge 501(c)(3) organizations 25% of their would-be property taxes, so long as the exempt organization owns at least $15 million worth of property;

- requires these cities or towns to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to describing the agreement between the municipality and the tax-exempt organizations; and

- allows these local ordinances and bylaws to have exemptions from payment and considerations of community benefits in lieu of cash contributions.

Importantly, this is a local option bill, which means that municipalities are allowed to require large, non-profit institutions to pay 25% of their would-be property taxes but do not have to. The language of this bill largely tracks Boston’s PILOT program but mandates (rather than requests) the payment of 25% of a large institution’s would-be taxes. It is not clear whether this mandate runs afoul of the Massachusetts Constitution, which requires properties in the same property class (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) to be taxed at the same rate. It is possible that the bill is meant to be a “fee” rather than a tax, in which case the funds should only be used for essential services.

During the 2021-22 session, Representative Uyterhoeven testified at the previous bill’s public hearing. She emphasized that the bill is for very large institutions and “not for churches, not for small kitchens, or anything like that, it’s really just for the large nonprofits, the health care facilities, universities. This comes from an equity issue around large nonprofits needing to pay their faire share to all of the things that municipal budgets serve them.” That said, the bill does not contemplate an exemption for churches, and it is possible that at least some churches have $15 worth of land and cannot afford the 25% of their would-be property taxes. It would be up to municipalities to include exemptions for specific organizations within their bylaws and ordinances, which may be politically difficult.

The City of Boston should opt-in

Bill H.2963 is currently with the Committee on Revenue. It is not clear that this bill has traction or will pass into law––the legislature has considered similar bills as early as 2013 and the bill was sent for study last session, often a quiet way to kill a bill.

However, if the bill does pass, Mayor Wu and her team should push to adopt an ordinance or bylaw given the City of Boston’s reliance on property taxes. Boston lawmakers should be conscious of their exemptions. One worry is that residents may make value judgments and target organizations that they do not like through a mandated fee.

Boston lawmakers should consider lowering the percentage of community benefits the City of Boston will accept. Although there is great value in community benefits, in practice they benefit individual residents rather than fund the City’s operating budget.

The Massachusetts legislature has an opportunity to fix a loophole in property taxes that allows large, private institutions to take advantage of their 501(c)(3) status to avoid paying property taxes. Bill H.2963 is a step in ensuring that these institutions start to pay their fair share and is a model for other states and municipalities dealing with similar challenges. If the bill becomes law, the City of Boston urgently needs to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to relieve economic pressure on residents and businesses, who currently fund the majority of the City’s operating budget.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

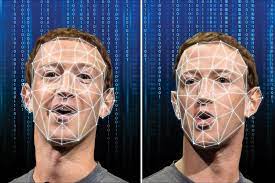

Revenge Porn and Deep Fake Technology: The Latest Iteration of Online Abuse

Revenge Porn

The rise of the digital age has brought many advancements to our society. But it has also enabled new forms of online harassment and abuse. Revenge porn (otherwise referred to as image-based sexual abuse or nonconsensual pornography) is a type of gender-based abuse in which sexually explicit photos or videos are shared without the consent of those pictured. The prevalence of cell phones and user-generated content websites has turned revenge porn into a common phenomenon. While some legislation has been passed to meet this rising threat, technology has evolved to the point that many of these statutes no longer meet the challenge of the current environment. State legislators have left wide loopholes in their revenge porn statutes, and the rise in Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new brand of revenge porn missing entirely from state statutes. Furthermore, the federal government has so far failed to make revenge porn in any form a criminal offense.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

Rise of Deep Fake Technology

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

We have now entered a new phase of exploitation: AI-manufactured nude photos. Technology users can now utilize the photos of real people to create pornographic images and videos. There are two types of AI-generated images that relate to the problem of revenge porn: “deep fakes” and “nudified” images. Deep fakes are created when an AI program is “trained” on a reference subject. Uploaded reference photos and videos are “swapped” with target images, creating the illusion that the reference subject is saying or participating in actions that they never have. U.S. intelligence officials acknowledged deep fake technology in their annual “worldwide threat assessment” for its ability to create convincing (but false) images or videos that could influence political campaigns. In the context of revenge porn, pictures and videos of a victim can be manipulated into a convincing pornographic image or video. AI technology can also be used to “nudify” existing images. After uploading an image of a real person, a convincing nude photo can be generated using free applications and websites. While some of these apps have been banned or deleted (for example, DeepNude was shut down by its creator in 2019 after intense backlash), new apps pop up in their places.

This technology will undoubtedly exacerbate the prevalence and severity of revenge porn – with the line of what’s real and what’s generated blurring together, folks are more at risk of their image being exploited. And this technology is having a disproportionate impact on women. Sensity AI tracked online deep fake videos and found that 90%-95% of them are nonconsensual porn, and 90% of those are nonconsensual porn of women. This form of gender-based violence was recently on display when a high-profile male video game streamer accessed deep fake videos of his female colleagues and displayed them during a live stream.

This technology also creates a new legal problem: does a nude image have to be “real” for a victim to recover damages? In Ohio, for instance, it is a criminal offense to knowingly disseminate “an image of another person” who can “be identified form the image itself or from information displayed in connection with the image and the offender supplied the identifying information” when the person in the image is “in a state of nudity or is engaged in a sexual act.” It is currently unclear if an AI-generated nude image constitutes “an image of another person...” under the law. Cursory research did not unearth any lawsuits alleging the unauthorized use of personal images in AI-generated pornography. In fact, after becoming a victim to deep fake pornography herself, famed actress Scarlett Johansson told the Washington Post that she “thinks [litigation is] a useless pursuit, legally, mostly because the internet is a vast wormhole of darkness that eats itself.” However, in early 2023, artists have filed a class-action lawsuit against companies utilizing Stable Diffusion for copyright violations. This lawsuit may signal that unwilling participants in AI-generated content may could find relief in the legal system.

Some states have tackled head-on the issue of deep fake technology as it relates to revenge porn and sexual exploitation. In Virginia, it is a Class 1 misdemeanor for the unauthorized dissemination or selling of a sexually explicit video or image of another person created by any means whatsoever (emphasis added). The statute goes on to state that “another person” includes a person whose image was used in creating, adapting, or modifying a video or image with the intent to depict an actual person and who is recognizable as an actual person by the person's face, likeness, or other distinguishing characteristic. But this Virginia law is not without fault. The statute states that the image must be of a person’s genitalia, pubic area, buttocks, or breasts. Therefore, an image of a person in a compromising position or that is merely sexually suggestive would likely not be covered by this statute.

Current Remedies are Insufficient

Revenge porn victims often bring tort claims, which may include invasion of privacy, intrusion on seclusion, intentional/negligent infliction of emotional distress, defamation, and others. Specific revenge porn statutes also allow for civil recovery in some states. But revenge porn statutes have flaws. In an article authored by Professor Rebecca Defino, there are three commonly cited critiques to revenge porn statutes. The first is that many of these statutes have a malicious intent or illicit motive requirement, which requires prosecutors to prove a particular mens rea. (921; see the aforementioned Ohio statute; Missouri criminal statute; Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 1040.13b(B)(2)). Second, many revenge porn statutes include a “harm” requirement, which is difficult to prove and requires victims to expose even more of their private life in a public arena. (921). And finally, the penalties are weak. (921). And even if a victim wins a case against a perpetrator, jail time for the perpetrator or small monetary settlements don’t provide victims what they often really desire – for their images to be taken off the Internet. The Netflix series called The Most Hated Man on the Internet shows the years long and deeply expensive journey to remove photos from a revenge porn website. While state revenge porn laws may assist victims with finding recourse, the process of removing images post-conviction can still be traumatizing and time-consuming.

While deep fake legislation is considered (or stalled) through state and federal governments, the private sector may be able to provide some solutions. A tool called “Take It Down” is funded by Meta Platforms (the owner of Facebook and Instagram) and operated by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The site allows anonymous individuals to create a digital “fingerprint” of real or deepfake image. That “fingerprint” is then uploaded to a database, which certain tech companies (including Facebook, Instagram, TikTok Yubo, OnlyFans, and Pornhub) have agreed to participate in, that will remove that image from their services. This technology is not without its own limitations. If the image is on a non-participating site (currently, Twitter has not committed to the project) or is sent via an encrypted platform (like WhatsApp), the image will not be taken down.

Additionally, if the image has been cropped, edited with a filter, turned into a meme, had an emoji added, or altered in other ways, the image is considered new and requires its own “fingerprint.”

While these are not easy problems to solve, the federal government can and should criminalize revenge porn, including AI-generated revenge porn. A federal statute would provide a stronger disincentive to create pornographic deep fakes through the threat of investigations by the FBI and prosecution by the Department of Justice. (927-928). Law professor Rebecca A. Delfino drafted the Pornographic Deepfake Criminalization Act, which makes the creation or distribution of pornographic deepfakes unlawful and allows the government to impose jail time and/or fines on defendants found guilty of the crime. (928-930). Perhaps more impactfully, the proposed act allows courts to issue the destruction of the image, compel content providers to remove the image, issue an injunction to prevent further distribution of the deep fake image, and award monetary damages to the victim. (930). The law is an imperfect tool in fighting against revenge porn and AI-generated pornographic deep fakes. But to the extent that legislators can provide additional support to victims, it is their obligation to do so.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.

Accelerated Public Health Modernization in Massachusetts

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and national movements for public health modernization, the Massachusetts Legislature tried to strengthen the Commonwealth’s public health during the summer of 2022. The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act (H.5014) (SAPHE 2.0) would have required local boards of health and regional health districts to comply with new minimum standards for public health service delivery. Governor Baker, however, proposed making the standards optional for municipalities, effectively killing the bill for the 2021-2022 legislative session. Fortunately, a new governor and legislature may provide some hope for this bill.

Public Health Modernization in Massachusetts

SAPHE 2.0 is a continuation of recent efforts by the Massachusetts Legislature to strengthen public health systems in the Commonwealth. In 2016, Governor Baker signed a legislative resolve establishing a special commission to “assess the effectiveness and efficiency of municipal and regional public health systems and to make recommendations regarding how to strengthen the delivery of public health services and preventive measures.” In 2019, the Special Commission on Local and Regional Public Health published a final report that found many local boards of health struggle to comply with public health service delivery statutes and regulations. More troubling, municipal compliance fell below national expectations set by frameworks like the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s 10 Essential Public Health Services, and the Public Health Accreditation Board's Foundational Public Health Services that defines the minimum set of services and capabilities each health department required for its voluntary national public health accreditation program. The Special Commission noted that Massachusetts has 351 local boards of health–the largest number within any state, due in part to the Commonwealth’s emphasis on local autonomy–rather than the boards organized by county in other states. As a result, Massachusetts boards lack the capacity to deliver necessary public health services compared to larger health departments in other states, which have greater resources. The Special Commission recommended establishing minimum standards for public health in Massachusetts, which could help local boards of health achieve compliance with state requirements and then work toward accreditation, and facilitating cross-jurisdictional service sharing arrangements, among other reforms.

In April 2020, Governor Baker signed An Act Relative to Strengthening the Local and Regional Public Health System into law. The Act established the “State Action for Public Health Excellence” (SAPHE) program that aimed to “improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery of local public health services” in the Commonwealth through funding and technical assistance related to cross-jurisdictional collaboration, data sharing, workforce development, and other domains. The Act also charged DPH with defining minimum standards for foundational public health services in Massachusetts to enhance governmental public health performance. This legislation, however, made these standards voluntary and aspirational. The Act incentivized participation through a grant program to fund municipalities involved in planning, capacity building, and implementation of cross-jurisdictional sharing arrangements. The Department of Public Health currently funds 41 grantees representing 76% of municipalities across the state.

SAPHE 2.0

The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act, dubbed “SAPHE 2.0,” builds upon the 2020 law to continue strengthening public health systems in the Commonwealth. Critically, the bill would require municipalities to meet DPH’s minimum public health standards and provide material support to municipalities. SAPHE 2.0 would have also augmented the existing grant program in two ways: expanding the availability of competitive grants (establishment of shared service arrangements and expansion of existing arrangements) and providing grants and technical assistance to help health departments with “limited operation capacity” to meet requirements. The House and Senate unanimously passed the bill on July 29, 2022.

The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act, dubbed “SAPHE 2.0,” builds upon the 2020 law to continue strengthening public health systems in the Commonwealth. Critically, the bill would require municipalities to meet DPH’s minimum public health standards and provide material support to municipalities. SAPHE 2.0 would have also augmented the existing grant program in two ways: expanding the availability of competitive grants (establishment of shared service arrangements and expansion of existing arrangements) and providing grants and technical assistance to help health departments with “limited operation capacity” to meet requirements. The House and Senate unanimously passed the bill on July 29, 2022.

Proponents of SAPHE 2.0 support standardization of public health performance to ensure all Massachusetts residents receive comprehensive, high-quality public health services. A coalition led by the Massachusetts Public Health Association (MPHA) advocated for the bill, emphasizing that the decentralized approach to public health service delivery in the Commonwealth “leads to extreme variability across municipalities.” The MPHA also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated underlying public health inequities and called on the Legislature to “invest in creating a stronger, more equitable system that will provide essential public health protections to all residents.”

Executive Disapproval

In August 2022, Governor Charlie Baker declined to sign the bill and returned it to the Legislature with significant proposed amendments. Governor Baker supported the bill’s objective to “provide high-quality, coordinated and more uniform public health services across the Commonwealth” but expressed concern about the lack of guaranteed state funding to complement performance requirements for municipalities, which creates the potential for unfunded mandates. He also expressed concern that the bill lacked provisions requiring municipalities to maintain their own current levels of public health funding as a condition of receiving support from DPH. Accordingly, Governor Baker proposed to not mandate that local boards of health meet minimum public health standards, but instead permit them to opt in to receive funding from DPH to meet those standards while requiring them to maintain their existing municipal funding levels for public health services.

The MPHA criticized the proposed amendments, indicating they would “entrench the patchwork of municipal policies that makes our local public health system both ineffective and inequitable” (email newsletter on September 27, 2022). However, Governor Baker’s rejection of the bill reflects the primary motivations against it: the potential for local boards of health to receive no state funding to support their compliance with minimum standards. The Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) echoed Governor Baker’s sentiments, indicating support for “the intent of the legislation” but noting “strong concerns that the measure as written could impose a new annual unfunded mandate on municipalities.” Delivering testimony on the proposed bill, the MMA noted that “as written, H. 5104 does not mandate that the state meet its obligation to financially support the outlined goals. Instead, the state’s responsibilities would be subject to appropriation, while municipalities would not have that flexibility, and would be forced to fund the new costs imposed by the Department of Public Health.”

The Path Forward

SAPHE 2.0 is a microcosm of perennial public health concerns: how to deliver high-quality services and ensure equitable distributions of health burdens and benefits with limited resources. Governmental public health’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare structural health inequalities and emphasized the need for effective public health services and infrastructure, but also revealed logistical challenges inherent in forcing decentralized entities to act in tandem.

Although SAPHE 2.0 has been defeated in the short term, its longer-term prospects look promising: Governor Maura Healy took office in January 2023, and the Joint Committee on Public Health is considering a newly refiled version of the proposal. Public health advocates will continue to champion modernization efforts to advance the optimal health of all communities in Massachusetts.

Shannon Gonick anticipates receiving her juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Shannon Gonick anticipates receiving her juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Boston T Party: Using Transatlantic Policymaking to Push Free Public Transit in Massachusetts

If you've lived anywhere near the Boston metropolitan area in the past few months, you will no doubt have faced a barrage of discussion in the media and manifestos about the prospects of making the T (Boston's public transport system) free for all riders. Mayor Michelle Wu has headed up the push to make the historic MBTA free and used it as a major issue in her Mayoral campaign. Mayor Wu wrote an Op-Ed in the Boston Globe as far back as January 2019 advocating for free public transit, citing improvements to air quality, economic mobility, racial equity. Wu even donned a golden, token style pendant with the classic T logo in many of her campaign advertisements. This in-vogue concept also has the support Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley and former Democratic candidate for governor and former state senator Ben Downing vowed to "make the T free by the end of his first term." Another former gubernatorial candidate state senator Sonia Chang-Diaz proposed a state-wide free public transportation agenda, starting with buses. There have been small steps toward this goal such as making three bus lines free for two years. This article is designed not to demonstrate the positives of free public transit, of which I am a strong proponent, but how we can make the program more palatable for those on Beacon Hill.