Category: Analysis

A Legal Tug-of-War between the Massachusetts State Auditor and the Legislature

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts finds itself at a constitutional crossroads as the legal tug-of-war unfolds between the State Auditor and the Legislature. In August 2023, the Massachusetts State Auditor, Diana DiZoglio, sent a letter to Attorney General Andrea Campbell stating she was conducting an audit of both the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives (the Legislature). This audit would include “budgetary, hiring, spending, and procurement information, information regarding active and pending legislation, the process for appointing committees, the adoption and suspension of legislative rules, and the policies and procedures of the Legislature.” However, Campbell responded that the auditor cannot unilaterally probe the Legislature without its consent. In this case, both Ronald Mariano, Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and Karen Spilka President of the Massachusetts Senate rejected DiZoglio’s audit. They reasoned that the financial documents of the legislature are made public and the other information DiZoglio is requesting violates the separation of powers. This conflict is not new but rather a historical tug-of-war between the branches of government and the delegation of powers. This debate requires a comprehensive analysis of statutory powers, historical positions, and constitutional considerations.

DiZoglio is asserting her power to conduct this audit under the State Auditor’s enabling statute, M.G.L. c. 11 § 12. Section 12 directs the State Auditor to audit “accounts, programs, activities and functions directly related to the aforementioned accounts of all departments, offices, commissions, institutions and activities of the commonwealth, including those of districts and authorities created by the general court and including those of the income tax division of the department of revenue.” The language that Campbell focused on was the meaning of “departments” and whether the Legislature was intended to be included in that term. Campbell scrutinized various cases and the texts of other statutes using this term concluding that “department” is more restricted than it appears. From a historical perspective, the term “department” appeared in the text of the statute in 1920 at the same time the Massachusetts’s general laws were enacted and when the Executive Branch was reorganized into “departments.” Upholding the precedent of her predecessors, Campbell adopted the view that “the word ‘department’ in statutes such as these should in general encompass only executive branch departments.”

DiZoglio is asserting her power to conduct this audit under the State Auditor’s enabling statute, M.G.L. c. 11 § 12. Section 12 directs the State Auditor to audit “accounts, programs, activities and functions directly related to the aforementioned accounts of all departments, offices, commissions, institutions and activities of the commonwealth, including those of districts and authorities created by the general court and including those of the income tax division of the department of revenue.” The language that Campbell focused on was the meaning of “departments” and whether the Legislature was intended to be included in that term. Campbell scrutinized various cases and the texts of other statutes using this term concluding that “department” is more restricted than it appears. From a historical perspective, the term “department” appeared in the text of the statute in 1920 at the same time the Massachusetts’s general laws were enacted and when the Executive Branch was reorganized into “departments.” Upholding the precedent of her predecessors, Campbell adopted the view that “the word ‘department’ in statutes such as these should in general encompass only executive branch departments.”

DiZoglio contends that the Auditor’s Office has a precedent for auditing the Legislature, citing historical reports conducted on various agencies. The Auditor’s Office originally was charged with collecting annual reports on various government agencies that was eventually transferred to the Office of the Comptroller when that office was created 1922. The pre-1923 reports provided a broad overview of the financial information specifically detailing how the Legislature could reduce its expenditures. Campbell pointed out that the information that the Auditor is currently requesting goes beyond the limited scope and the functions the Auditor currently possesses. The reports from 1923-1971 were once again narrowly construed to certain entities “under the purview of the Legislature,” but not the Legislature as whole as DiZoglio is attempting to do now. From 1972-1990, the Auditor conducted audits of three specific legislative entities and reporting on their expenditures, appropriations, and other miscellaneous income. In 1978, the Senate stopped complying with the Auditor’s audits after the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decided Westinghouse Broadcasting Co. v. Sergeant-at-Arms of General Court (Mass. 1978). In Westinghouse, the Court held that “the records generated by the Legislature could be made available to outsiders only at the discretion of the House and Senate leadership.” The Senate cited this holding to restrict the Auditor’s access to certain records. From 1990 until 2023, the Auditor conducted three narrow audits of legislative operations: addressing overpayments to a court officer in 1992, IT-related controls by the Sergeant-at-Arms in 2002, and Legislative Information Services in 2006. In contrast, the Auditor’s proposed broad audit will scrutinize core legislative powers rather than specific issues or entities.

The enforcement of orders for document production against the Legislature raises serious constitutional questions related to the separation of powers. These concerns were raised by former State Auditors, Suzanne Bump and A. Joseph DeNucci. If the Auditor moves forward with the audit, it would require the Superior Court to enforce those orders against the Legislature’s consent. As provided by the Massachusetts Constitution, the legislative branch has the authority to establish its own rules and proceedings. Thus, if the Judiciary enforced the audit against the Legislature, it would be interfering directly with the Legislature’s core functions. Although Attorney General Campbell did not go so far as to define the extent of the constitutional limitations, it did acknowledge the potential for such an issue to arise.

The enforcement of orders for document production against the Legislature raises serious constitutional questions related to the separation of powers. These concerns were raised by former State Auditors, Suzanne Bump and A. Joseph DeNucci. If the Auditor moves forward with the audit, it would require the Superior Court to enforce those orders against the Legislature’s consent. As provided by the Massachusetts Constitution, the legislative branch has the authority to establish its own rules and proceedings. Thus, if the Judiciary enforced the audit against the Legislature, it would be interfering directly with the Legislature’s core functions. Although Attorney General Campbell did not go so far as to define the extent of the constitutional limitations, it did acknowledge the potential for such an issue to arise.

The Attorney General’s Office holds firm that the Auditor’s current authority does not extend to auditing the Legislature without consent. In response, the Auditor sought to ask the public whether she has the authority to audit the legislature through a question on 2024 ballot. DiZoglio’s proposal received over 100,000 signatures and is on track to be included on the 2024 state-wide ballot. First, however, the Legislature reviews the proposal, with the Judiciary Committee holding a tense hearing in March 2024. DiZoglio testified,

“Our office provides a resource to this commonwealth. Contrary to the narrative that some legislators and their supporters have been spinning, [my] office is not the FBI. We do not go in and raid people’s offices. We do not have the ability to toss desks. Our staff conducts performance audits. Audits. The amount of opposition to audits from this body is deeply, deeply disturbing and concerning on so many levels.”

However, Jeremy Paul, a law professor at Northeastern University, testified that the courts may invalidate the new law if the voters approve it in November.

“I submit that the power to audit may well turn out to be the power to destroy. It’s one thing to push for greater transparency in legislative operations so that the public is given more information. It’s entirely another to give an elected official inside the elected branch discretion to decide which legislators can be called to account for what reasons and when.”

Thus, the saga continues, serving as a constant reminder of the delicate balance that needs to be struck within our democratic system between responsibility, transparency, and the preservation of constitutional principles.

Abigail Rooney West anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Abigail Rooney West anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

The Push and Pull of Municipal Fossil Fuel Bans in Massachusetts

In 2019, Brookline, Massachusetts became the first municipality outside of California to ban fossil fuels in new construction. The move was part of a growing movement among cities and towns to ban fossil fuel infrastructure, such as hookups for oil or natural gas use, in newly constructed buildings. Fossil fuel bans of this nature typically aim to curb emissions from energy use in buildings, which in many municipalities is the leading source of emissions, through electrification. Electricity use in buildings produces less carbon emissions than burning oil and gas directly and those emissions will continue to decrease as more renewable resources are added to the electricity grid.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Meanwhile, in the time between when Brookline passed its first fossil fuel ban and when the Attorney General issued its decision about the legality of the second ban, dozens of other Massachusetts municipalities became interested in enacting fossil fuel bans of their own. Some of these municipalities submitted home rule petitions to the Massachusetts legislature, asking the legislature to grant their individual municipalities the authority to ban fossil fuel infrastructure on a case-by-case basis. State Representative Tami Gouveia and State Senator Jamie Eldridge of Acton also introduced a bill during the 2021–2022 session that would have granted every municipality in the commonwealth the power to adopt a requirement for all-electric construction without passing and submitting a home rule petition.

The result was a compromise: The legislature passed An Act Driving Clean Energy and Offshore Wind in August of 2022. The law, among other things, authorized a pilot program enabling up to ten cities and towns to adopt and amend ordinances or by-laws to require new building construction or major renovation projects to be fossil fuel-free. The Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER) was tasked with developing the pilot program and deciding which municipalities would participate. Among requirements for cities and towns seeking to join the pilot program for fossil fuel bans is having a minimum of ten percent affordable housing.

DOER has already received more than ten applications from Massachusetts cities and towns wishing to join the pilot program, but under the draft regulations DOER published in February of this year, municipalities would have to wait until early 2024 at the earliest to implement their bans. This long period for implementation has disturbed members of the legislature who championed and passed the pilot program into law. Senator Michael Barrett, the Senate Chair of the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy recently told GBH News that the proposal would “delay the entire process much longer than the Legislature ever imagined.” Pressure from both the legislature and the municipalities seeking to join the pilot program will likely continue to mount as the group of cities and towns now includes the City of Boston, the largest city in the commonwealth. With advocacy groups concerned that the delay combined with limiting the pilot program to ten municipalities will hold the commonwealth back from meeting its goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050, legislators may be reconsidering the more conservative approach they took by passing the pilot program rather than blanket approval for cities and towns to enact fossil fuel bans.

Opponents and those concerned about the impacts of fossil fuel bans, however, may be heartened by the delay. Governor Charlie Baker considered vetoing the energy bill because of the fossil fuel ban pilot program because of the possibility that banning fossil fuels in new construction might make it more difficult to build affordable housing. In a state experiencing what many characterize as an affordable housing crisis, this concern is not uncommon, the thought process being that if there is inconsistency in requirements for developers between municipalities, developers, especially developers of affordable housing, will prioritize projects in communities with fewer or less expensive requirements. Many of the cities and towns that have already stepped forward to join the pilot program are fairly wealthy and may not be as concerned with the affect of a fossil fuel ban on the costs of housing development.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

The future of fossil fuel-free building in Massachusetts is uncertain. The legislature may choose to take a more aggressive approach than it did during the last session, or it may wait to see how DOER’s implementation of the pilot program goes, leaving Massachusetts cities and towns and developers to continue to innovate on their own. States are often called “laboratories of democracy,” but when it comes to issues like climate change, where municipalities acting individually may be able to make a large impact, that label may better suit cities and towns as they try again and again to form creative solutions where their state legislatures fall short.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

End the Request: It’s Time for Boston’s Biggest Landowners to Pay Their Fair Share

For the second time, Massachusetts State Representative Erika Uyterhoeven (D-Somerville) filed a bill concerning payments in lieu of taxes to cities and towns. This bill would strengthen and codify a Boston program, which requests payment from certain institutions that do not pay property taxes. It is important that this bill passes during the 2023-24 session because, without it, Boston (and other municipalities) will continue to subsidize large, private organizations at the expense of its own residents.

The City of Boston’s budget

The City of Boston’s operating budget consists of revenue from property taxes, state aid, local revenue, and, to a small extent, non-recurring revenue (e.g., funds from the American Rescue Plan Act). This revenue is used to fund programs and services, including public education, public safety, city departments, and transportation. Property taxes are consistently the City’s largest source of revenue, and its share size continues to increase as state aid decreases. For example, 74% of the City’s revenue is derived from property taxes this year compared to 52% in 2002.

Boston residential taxpayers currently pay $10.74 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge taxpayers spend $5.86; Somerville taxpayers spend $10.34 and Medford taxpayers spend $8.65. Boston commercial taxpayers, including small businesses pay $24.68 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is also higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge commercial tax payers spend $11.23, Somerville commercial taxpayers spend $17.35, and Medford commercial taxpayers spend $16.56.

Part of the reason why Boston’s property taxes are so high is that Boston’s tax base is constrained. Boston’s geographic region is relatively small and is home to many tax-exempt institutions.

52% of Boston’s area is tax exempt.

Tax-exempt areas include public land owned by the city, state, and federal government along with private land owned by universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions. These institutions are not required to pay property taxes as nonprofit charitable organizations under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. In Boston, this includes large, private institutions––like Mass General Brigham, Harvard, Boston University, and Northeastern––that together own over $14 billion of Boston’s real estate.

These large institutions do make some financial contributions to the city of Boston via the Payment in Lieu of Tax (“PILOT”) program. The PILOT program asks educational, medical, and cultural institutions with more than $15 million worth of tax-exempt property to make voluntary payments to the City of Boston. These contributions are supposed to be 25% of the would-be property taxes, and up to 50% of this payment can be in the form of “community benefits.” The 25% represents a “fair share” because large institutions’ use of essential services, such as fire safety, roads, public transportation, and sewage disposal generally make up 25% of a municipality’s budget.

The PILOT task force defines Community benefits “as services that directly benefit City of Boston residents; support the City’s mission and priorities with the idea in mind that the City would support such an initiative in its budget if the institution did not provide it; emphasize ways in which the City and the institution can collaborate to address shared goals; and, are quantifiable.” For example, these services can take the form of individual scholarships and job training initiatives. Other examples include summer camp and after school activities, preventative medical care, and maintenance of public spaces.

PILOT does not go far enough

Institutions often do not fulfill their PILOT requests from the City of Boston. During the 2022 fiscal year, Northeastern met 67% of its PILOT request. Boston University and Harvard did better, meeting 80% and 79% of their PILOT requests, respectively. However, these institutions tend to max out their community benefits. For example, during the 2022 fiscal year, the City of Boston requested $66,709,087 from educational institutions and received $30,793,921 in community benefits and only $14,788,450 in cash contributions. Here, it is worth emphasizing that $66,709,087 is only one quarter of what these institutions would pay if their properties were not tax-exempt.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Boston should be able to increase the amount of money generated from the city’s PILOT program to alleviate the pressure on its residents and small business owners and to ensure that large institutions pay their fair share for essential services. Changing these institutions from 501(c)(3) status to require payment of property taxes is likely a political and bureaucratic nightmare, especially given these institutions’ reliance on the nonprofit status. That said, some Massachusetts legislators are taking steps to ensure that universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions start to pay their fair share.

Bill H.2963

Representative Erika Uyterhoeven refiled Bill H.2963, An Act Relative to Payments In Lieu of Taxation by Organizations Exempt from the Property Tax on January 19 this year. The proposed bill:

- allows cities or towns to charge 501(c)(3) organizations 25% of their would-be property taxes, so long as the exempt organization owns at least $15 million worth of property;

- requires these cities or towns to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to describing the agreement between the municipality and the tax-exempt organizations; and

- allows these local ordinances and bylaws to have exemptions from payment and considerations of community benefits in lieu of cash contributions.

Importantly, this is a local option bill, which means that municipalities are allowed to require large, non-profit institutions to pay 25% of their would-be property taxes but do not have to. The language of this bill largely tracks Boston’s PILOT program but mandates (rather than requests) the payment of 25% of a large institution’s would-be taxes. It is not clear whether this mandate runs afoul of the Massachusetts Constitution, which requires properties in the same property class (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) to be taxed at the same rate. It is possible that the bill is meant to be a “fee” rather than a tax, in which case the funds should only be used for essential services.

During the 2021-22 session, Representative Uyterhoeven testified at the previous bill’s public hearing. She emphasized that the bill is for very large institutions and “not for churches, not for small kitchens, or anything like that, it’s really just for the large nonprofits, the health care facilities, universities. This comes from an equity issue around large nonprofits needing to pay their faire share to all of the things that municipal budgets serve them.” That said, the bill does not contemplate an exemption for churches, and it is possible that at least some churches have $15 worth of land and cannot afford the 25% of their would-be property taxes. It would be up to municipalities to include exemptions for specific organizations within their bylaws and ordinances, which may be politically difficult.

The City of Boston should opt-in

Bill H.2963 is currently with the Committee on Revenue. It is not clear that this bill has traction or will pass into law––the legislature has considered similar bills as early as 2013 and the bill was sent for study last session, often a quiet way to kill a bill.

However, if the bill does pass, Mayor Wu and her team should push to adopt an ordinance or bylaw given the City of Boston’s reliance on property taxes. Boston lawmakers should be conscious of their exemptions. One worry is that residents may make value judgments and target organizations that they do not like through a mandated fee.

Boston lawmakers should consider lowering the percentage of community benefits the City of Boston will accept. Although there is great value in community benefits, in practice they benefit individual residents rather than fund the City’s operating budget.

The Massachusetts legislature has an opportunity to fix a loophole in property taxes that allows large, private institutions to take advantage of their 501(c)(3) status to avoid paying property taxes. Bill H.2963 is a step in ensuring that these institutions start to pay their fair share and is a model for other states and municipalities dealing with similar challenges. If the bill becomes law, the City of Boston urgently needs to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to relieve economic pressure on residents and businesses, who currently fund the majority of the City’s operating budget.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Congestion Pricing: Addressing The True Cost of Cars

One of the most heartening social trends of the last couple of years has been a recognition of the true costs of car use in cities. Whether approaching it from the stance of climate change, health effects from air quality, physical safety on the roads, or social fragmentation from structures that isolate and alienate people, it has become increasingly clear that we do not properly value our roads. One policy with great potential to address all these concerns, while generating considerable revenue that could support mass transit in cities, is congestion pricing of key roads in urban centers.

The idea behind congestion pricing is that roadways are incredibly valuable real estate, which people do not pay to use (outside of some tolling on bridges and specific toll roads). The free use of the roads imposes significant social costs on the city's inhabitants through bumper-to-bumper traffic, costing people time, and polluting the air. A congestion pricing system would impose a toll on entrants to designated zones. This would reduce traffic by imposing the true costs of using the road, and hopefully, diverting people to use mass transit or other forms of transportation. The beneficial effects would range from clearing congestion, to reducing air pollution, to generating significant revenue for the city.

The idea behind congestion pricing is that roadways are incredibly valuable real estate, which people do not pay to use (outside of some tolling on bridges and specific toll roads). The free use of the roads imposes significant social costs on the city's inhabitants through bumper-to-bumper traffic, costing people time, and polluting the air. A congestion pricing system would impose a toll on entrants to designated zones. This would reduce traffic by imposing the true costs of using the road, and hopefully, diverting people to use mass transit or other forms of transportation. The beneficial effects would range from clearing congestion, to reducing air pollution, to generating significant revenue for the city.

This is no longer merely a thought experiment either. Notably, cities including London, Stockholm, and Singapore, have all implemented congestion pricing in their city centers to great positive effect. They generally see reduced car congestion, but also interestingly, greater total numbers of people accessing the city, as they come in via alternate methods. This increases economic value to the city without imposing any of the normal car related costs.

No American city has successfully implemented this policy yet, but New York is currently in the middle of a now 5 year long battle to try. In 2019, the New York State legislature passed, in the state budget, a law permitting the city of New York to implement a congestion pricing plan. Curiously, New York City does not control its own road system, and is therefore dependent on the state to give permission to implement such a project. This is relatively common in the U.S. and is in tension with the age-old principle of local control. It also raises a potential problem where a star city in a state drives a significant portion of that state’s revenue, but has strong political disagreements with the state government. In New York the success of the plan at the state level was over 50 years in the making. New York State had frequently prevented the city from implementing similar congestion pricing programs in the past, when the city had tried to reduce traffic.

Despite state approval, congestion pricing in New York has been stuck in limbo, in part due to federal law. Title 23 of the Federal Code prohibits municipalities from imposing tolls on roads constructed or maintained with federal funding, which include several New York City roads. To impose tolls, New York had to enlist in the Federal Highway Administration's Value Pricing Pilot Program (VPPP), which gives up to 15 cities or states special permission to experiment with toll related projects on federally funded roads. Congestion pricing plan falls under the purview of the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) because it is enrolled in the VPPP.

Passed in 1970, NEPA mandates environmental review of federal projects. While proponents argue that NEPA is an essential defense for the environment from human exploitation (both for its own sake and also to protect our habitat), critics traditionally argue it prevents profitable projects. Now environmentally minded advocates are increasingly frustrated with NEPA’s requirements. They argue NEPA’s onerous procedural requirements, which often require millions of dollars and years of effort, are inhibiting projects that would benefit the environment, violating its fundamental purpose.

It is clearly the case in New York right now that the city is suffering from these unnecessary delays. It took 2 full years just for the federal government to determine whether the appropriate environmental review was a relatively basic Environmental Assessment, or a complete Environmental Impact Assessment for the project and another 2 years to issue the determination report. Now, going on 5 years from initial passage, the city is still waiting for a final determination if the project is viable. All of this for a project that requires the city to build almost no physical infrastructure, and would dramatically reduce emissions and air pollution by reducing the number of cars driving in New York.

It is clearly the case in New York right now that the city is suffering from these unnecessary delays. It took 2 full years just for the federal government to determine whether the appropriate environmental review was a relatively basic Environmental Assessment, or a complete Environmental Impact Assessment for the project and another 2 years to issue the determination report. Now, going on 5 years from initial passage, the city is still waiting for a final determination if the project is viable. All of this for a project that requires the city to build almost no physical infrastructure, and would dramatically reduce emissions and air pollution by reducing the number of cars driving in New York.

The FHWA can remedy this issue by assigning congestion pricing projects a Categorical Exclusion (CE). A CE is used for projects that are known not to have negative environmental impacts. It exempts them from the entire Environmental Impact Statement and Environmental Assessment process. It is commonly used in projects where there will not be significant physical infrastructure created, much like the congest program. The programs would still have to present reasons why they should be granted the exclusion, so this will not totally eliminate any environmental review, but it will bring the level of review in line with the risks that the project actually presents.

New York’s experience shows the complex thicket of legislation and regulation that creative environmentalists must navigate in order to successfully pursue valuable projects. Congestion pricing is a perfect example because it is so cheap to implement, the primary difficulty should be political, in getting state legislatures to pass laws giving permission for cities to enact it. More American cities including San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle have shown interest but have shown extreme caution in part because they know how difficult the implementation will be. Instead of trusting legislators and representatives to work on behalf of city residents, needlessly complex and blunt regulations are stepping in the way and forcing us to continue to choke cities in idling car fumes.

Peter Kaplan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Peter Kaplan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

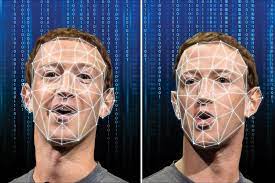

Revenge Porn and Deep Fake Technology: The Latest Iteration of Online Abuse

Revenge Porn

The rise of the digital age has brought many advancements to our society. But it has also enabled new forms of online harassment and abuse. Revenge porn (otherwise referred to as image-based sexual abuse or nonconsensual pornography) is a type of gender-based abuse in which sexually explicit photos or videos are shared without the consent of those pictured. The prevalence of cell phones and user-generated content websites has turned revenge porn into a common phenomenon. While some legislation has been passed to meet this rising threat, technology has evolved to the point that many of these statutes no longer meet the challenge of the current environment. State legislators have left wide loopholes in their revenge porn statutes, and the rise in Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new brand of revenge porn missing entirely from state statutes. Furthermore, the federal government has so far failed to make revenge porn in any form a criminal offense.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

Rise of Deep Fake Technology

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

We have now entered a new phase of exploitation: AI-manufactured nude photos. Technology users can now utilize the photos of real people to create pornographic images and videos. There are two types of AI-generated images that relate to the problem of revenge porn: “deep fakes” and “nudified” images. Deep fakes are created when an AI program is “trained” on a reference subject. Uploaded reference photos and videos are “swapped” with target images, creating the illusion that the reference subject is saying or participating in actions that they never have. U.S. intelligence officials acknowledged deep fake technology in their annual “worldwide threat assessment” for its ability to create convincing (but false) images or videos that could influence political campaigns. In the context of revenge porn, pictures and videos of a victim can be manipulated into a convincing pornographic image or video. AI technology can also be used to “nudify” existing images. After uploading an image of a real person, a convincing nude photo can be generated using free applications and websites. While some of these apps have been banned or deleted (for example, DeepNude was shut down by its creator in 2019 after intense backlash), new apps pop up in their places.

This technology will undoubtedly exacerbate the prevalence and severity of revenge porn – with the line of what’s real and what’s generated blurring together, folks are more at risk of their image being exploited. And this technology is having a disproportionate impact on women. Sensity AI tracked online deep fake videos and found that 90%-95% of them are nonconsensual porn, and 90% of those are nonconsensual porn of women. This form of gender-based violence was recently on display when a high-profile male video game streamer accessed deep fake videos of his female colleagues and displayed them during a live stream.

This technology also creates a new legal problem: does a nude image have to be “real” for a victim to recover damages? In Ohio, for instance, it is a criminal offense to knowingly disseminate “an image of another person” who can “be identified form the image itself or from information displayed in connection with the image and the offender supplied the identifying information” when the person in the image is “in a state of nudity or is engaged in a sexual act.” It is currently unclear if an AI-generated nude image constitutes “an image of another person...” under the law. Cursory research did not unearth any lawsuits alleging the unauthorized use of personal images in AI-generated pornography. In fact, after becoming a victim to deep fake pornography herself, famed actress Scarlett Johansson told the Washington Post that she “thinks [litigation is] a useless pursuit, legally, mostly because the internet is a vast wormhole of darkness that eats itself.” However, in early 2023, artists have filed a class-action lawsuit against companies utilizing Stable Diffusion for copyright violations. This lawsuit may signal that unwilling participants in AI-generated content may could find relief in the legal system.

Some states have tackled head-on the issue of deep fake technology as it relates to revenge porn and sexual exploitation. In Virginia, it is a Class 1 misdemeanor for the unauthorized dissemination or selling of a sexually explicit video or image of another person created by any means whatsoever (emphasis added). The statute goes on to state that “another person” includes a person whose image was used in creating, adapting, or modifying a video or image with the intent to depict an actual person and who is recognizable as an actual person by the person's face, likeness, or other distinguishing characteristic. But this Virginia law is not without fault. The statute states that the image must be of a person’s genitalia, pubic area, buttocks, or breasts. Therefore, an image of a person in a compromising position or that is merely sexually suggestive would likely not be covered by this statute.

Current Remedies are Insufficient

Revenge porn victims often bring tort claims, which may include invasion of privacy, intrusion on seclusion, intentional/negligent infliction of emotional distress, defamation, and others. Specific revenge porn statutes also allow for civil recovery in some states. But revenge porn statutes have flaws. In an article authored by Professor Rebecca Defino, there are three commonly cited critiques to revenge porn statutes. The first is that many of these statutes have a malicious intent or illicit motive requirement, which requires prosecutors to prove a particular mens rea. (921; see the aforementioned Ohio statute; Missouri criminal statute; Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 1040.13b(B)(2)). Second, many revenge porn statutes include a “harm” requirement, which is difficult to prove and requires victims to expose even more of their private life in a public arena. (921). And finally, the penalties are weak. (921). And even if a victim wins a case against a perpetrator, jail time for the perpetrator or small monetary settlements don’t provide victims what they often really desire – for their images to be taken off the Internet. The Netflix series called The Most Hated Man on the Internet shows the years long and deeply expensive journey to remove photos from a revenge porn website. While state revenge porn laws may assist victims with finding recourse, the process of removing images post-conviction can still be traumatizing and time-consuming.

While deep fake legislation is considered (or stalled) through state and federal governments, the private sector may be able to provide some solutions. A tool called “Take It Down” is funded by Meta Platforms (the owner of Facebook and Instagram) and operated by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The site allows anonymous individuals to create a digital “fingerprint” of real or deepfake image. That “fingerprint” is then uploaded to a database, which certain tech companies (including Facebook, Instagram, TikTok Yubo, OnlyFans, and Pornhub) have agreed to participate in, that will remove that image from their services. This technology is not without its own limitations. If the image is on a non-participating site (currently, Twitter has not committed to the project) or is sent via an encrypted platform (like WhatsApp), the image will not be taken down.

Additionally, if the image has been cropped, edited with a filter, turned into a meme, had an emoji added, or altered in other ways, the image is considered new and requires its own “fingerprint.”

While these are not easy problems to solve, the federal government can and should criminalize revenge porn, including AI-generated revenge porn. A federal statute would provide a stronger disincentive to create pornographic deep fakes through the threat of investigations by the FBI and prosecution by the Department of Justice. (927-928). Law professor Rebecca A. Delfino drafted the Pornographic Deepfake Criminalization Act, which makes the creation or distribution of pornographic deepfakes unlawful and allows the government to impose jail time and/or fines on defendants found guilty of the crime. (928-930). Perhaps more impactfully, the proposed act allows courts to issue the destruction of the image, compel content providers to remove the image, issue an injunction to prevent further distribution of the deep fake image, and award monetary damages to the victim. (930). The law is an imperfect tool in fighting against revenge porn and AI-generated pornographic deep fakes. But to the extent that legislators can provide additional support to victims, it is their obligation to do so.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.

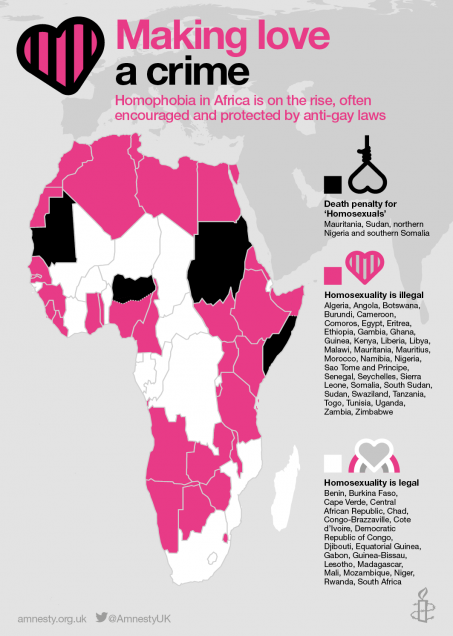

The Movement to Repeal a Colonial-Era Sodomy Law in Namibia

Namibia, located in Southern Africa, is, in terms of public opinion, one of the most LGBTQ+ tolerant countries on the continent. However, sodomy is still criminalized under Roman-Dutch common law, discrimination of LGBTQ+ people is legal, and same-sex marriages are not recognized by the courts. While all of these issues work in tandem, right now, the greatest threat to the rights of LGBTQ+ people in the country is the unconstitutional Combatting Immoral Practices Act of 1980. Activists have been working diligently to bring attention on both domestic and international scales to this injustice and the country’s leadership have shown that they are open to a shift in the status quo.

History of LGBTQ+ People in Namibia

Many modern-day groups in Namibia have historically engaged in same-sex marriages, sexual intercourse, and tradition. Some of these groups include the Khoikhoi, Ovambo, Nama, Herero, and Himba peoples. Additionally, the Ovambo people have the tradition of the esenge, where people assigned as male at birth would dress like women, perform womanly duties, and marry men. It is believed by the Ovambo that these people were possessed by female spirits. (173-242) The first anti-sodomy trials in modern-day Namibia occurred while it was under German colonial rule: four Europeans were banished from the colony for violating paragraph 145 of the German code, which criminalized men having sex with men. (106) When Namibia became a mandated territory of South Africa in 1920, South Africa implemented their Roman-Dutch common law on the country, including their anti-sodomy law. (116) Since Namibian independence in 1990, Namibia has never prosecuted anyone under their sodomy common law (9), however, the politicization of homophobia and the Combatting Immoral Practices Act of 1980 make the legal landscape of the nation hostile to LGBTQ+ individuals.

While anti-sodomy laws are the result of colonization, politicians and judges in Namibia have shifted that narrative by using rhetoric claiming that LGBTQ+ people are actually the “colonial import.” In the late 90’s and early 2000’s, politicians were often asked by media about their thoughts on LGBTQ+ individuals, with some going so far as to say that they wish to “eliminate” LGBTQ+ people. An unenforced 2001 request from the President to, “arrest, imprison, and deport homosexuals and lesbians found in Namibia,” went even further in politicizing homophobia for the sake of perceived political gain. In the 2010’s, political parties, both those in power and opposition groups, made efforts to make homophobia a platform of their parties.

The Combating Immoral Practices Act of 1980

At the common law, sodomy is considered a Schedule I offense (along with rape, murder, and other serious crimes), which means that officers can arrest a suspected sodomizer without a warrant and can utilize deadly force during the arrest. (10) Additionally, while the criminalization of same-sex (male only) sodomy is baked into the common law of the country, the Combatting Immoral Practices Act of 1980 strengthens the legal discrimination against LGBTQ+ people in Namibia. (103) While this law does not make homosexuality itself illegal, it criminalizes certain “immoral” sexual acts, which in combination with common law, includes sodomy, mutual masturbation, and oral sex. (12) Additionally, it is important to note that while this act applies to all members of society, certain provisions within it can easily be interpreted to target LGBTQ+ individuals for “committing immoral acts.” These provisions include sections 7 and 8, which condemn the enticing of and commission of immoral acts. Additionally, under the act, the owner of a home that permits “immoral acts'' to occur within it is subject to punishment. The term “immoral act,” is never defined in the legislation, creating an issue of vagueness and notice concerns for those that could be charged under the act. Given that this law does not define “immoral acts,” things as simple as a same-sex kiss in the street could be interpreted as illegal. An example of one of the harmful interpretations of this act is the Namibian government’s decision to deny prisoners access to condoms, stating that sexual activities between prisoners in a male prison would be “immoral practices.” (16)

As previously noted, vagueness is a particularly large concern within the confines of the act. For example, section 17(1) of the act criminalizes the manufacturing, selling, or supplying of “any article which is intended to be used to perform an unnatural sexual act.” This vagueness led sex shops to bring suit to the Namibian High Court to challenge the constitutionality of this language, as it could impede on their constitutional right to carry on a business. The Court found the “unnatural sexual act” language unconstitutionally vague as it did not provide any guidance on what these were. Additionally, the Court found that “‘unnatural’ involves a value judgment varying from country to country, race to race, and age to age; it has little if any objective content.” The Law Reform and Development Commission of Namibia believes that, given this ruling, “the common law crime of ‘unnatural sexual offenses’ would be similarly unconstitutional.” They base this belief on two hypotheses: 1) that it limits other constitutional rights, such as the right to privacy and 2) that it is “an affront to the rule of law” because its vagueness does not properly put people on alert of what specific behaviors could be criminalized. (27-28)

Efforts to Advocate for LGBTQ+ Individuals in Namibia

According to the Namibian Constitution, all laws in effect at the time of independence, including common law, will continue to be in effect until Parliament repeals them or the Court rules them to be unconstitutional. (Art. 66-1) In 2019, the Law Reform and Development Commission of Namibia identified the criminalization of sodomy and of “unnatural sexual offenses” to be obsolete laws. With the funding and advocacy of nonprofits and civil society groups, they were able to complete a report to Namibia’s Minister of Justice in 2020 advocating for repeal. The Commission cites to the Ombudsman’s 2013 Baseline Study Report on Human Rights in Namibia and the Parliament’s National Human Rights Action Plan 2014-2019 as supporting sources for their contention that this “vulnerable group” of LGBTQ+ individuals is unfairly discriminated against and criminalized for constitutionally protected behavior. (1-2) The Commission believes that the constitutional rights being harmed by this law are the right to be equally protected under the law, the right to be free from discrimination based on sex, the right to dignity, and the right to privacy. (12-27) The end of the report includes an appendix with draft legislation to be introduced by the Minister of Justice to Parliament to repeal these laws (67-68). In response, the Namibian Justice Minister, Yvonne Dausab, announced an intention to propose the repeal of this legislation.

Civic society groups have been at the forefront of pushing these changes. Some of these groups have joined together in a coalition called the Diversity Alliance of Namibia (DAN). Namibia also has the Outreach Health drop in center, which was the first LGBTQ+ health center in the country. Additionally, in 2021, the Namibia Equal Rights Movement organized the largest pride parade in the country’s history, advocating for the repeal of the laws criminalizing LGBTQ+ people. My friend and former colleague, Omar Van Reenen, is an organizer with Equal Namibia, a youth-led movement advocating for constitutional protections for LGBTQ+ people in Namibia. On an Africa Good Morning episode, Van Reenen stated that, “[t]he Constitution mandates protection of all minority and vulnerable groups. LGBTQ+ people are not asking for 'more rights' than heterosexual Namibians. They are asking for the 'exact same rights', the exact same liberties and exact same privileges under the Constitution.”

Rose Collins graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Rose Collins graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Voter Suppression Laws in the Wake of Democratic Control of the Presidency and Senate

Georgia gained national attention in the 2020 election when the predominantly red state broke its 24-year streak of voting for Republican candidates in U.S. Presidential Elections. It went on to make history in early 2021 when the electorate flipped the U.S. Senate and elected Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to the U.S. Senate, respectively the first Black and Jewish Senators from Georgia.

A large part of this victory both in the White House and the Senate is attributed to Stacey Abrams, the Democrat gubernatorial candidate in Georgia’s 2018 election. Abrams’ gubernatorial campaign was unsuccessful, in large part because of voter suppression, but rather than wallow in defeat and fade into the background, Abrams became a loud, powerful voice—speaking against voter suppression and registering hundreds of thousands of voters in Georgia.

And now Republicans—in Georgia and across the nation—formally responded, pushing a huge new wave of voter suppression tactics in the name of “election integrity.”

S.B. 71

Among other legislation, Republicans in the Georgia Senate have proposed S.B. 71, which would change the definition of absentee voter entirely. For the past 15 years or so, Georgia has been a “no excuse needed” absentee voting state, but this bill would require people who wish to vote absentee to

- Be physically absent from their precinct during the election;

- Be able to perform any of the “official acts or duties” connected to the election;

- Be absent because of physical disability or because you’re required to give constant care to someone who is disabled;

- Be observing a religious holiday;

- Be required to remain on duty for the “protection of the health, life, or safety of the public”; or

- Be at least 65-years-old.

These extremely limited exceptions would put even more emphasis on the luxury and privilege of time. Many people cannot take an hour (or more) out of their daily schedules—balancing child care, housing matters, and work among the other minutiae of modern life—to go to the polls. The oft-used argument to that is “well, there are plenty of precincts where you can get in and out in 10 minutes.” And while that may be accurate, the problem is inherent in the argument itself: that it isn’t true of every precinct; and issues with fewer voting machines, voter purges, and, therefore, long waits tend to disproportionately affect liberal-voting communities in Republican controlled states.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

Other Voter Suppression Legislation

Throughout the nation, state legislatures have begun putting forth bills that would restrict voting access—in fact, over four times more legislation that would restrict voting has been proposed than was proposed this time last year.

Georgia is not alone in limiting absentee voting. Nine other states have proposed bills that would either eliminate “no excuse” voting or crack down on the requirements for absentee voting where “excuse” voting is already in place. Other bills make it more difficult to obtain ballots in the first place by changing the laws concerning permanent early voter lists. Some measures go so far as to eliminate permanent early voter lists (which would force people now on those lists to take more steps to vote every year; Arizona S.B. 1678, Hawaii H.B. 1262, and New Jersey S.B. 3391) while others would reduce how long someone remains on the permanent absentee voter list (Florida S.B. 90).

Other proposals concern stricter voter ID requirements—a long contentious aspect of voter suppression. States that do not currently require photo IDs to vote are considering requiring them in the future, other states are trying to restrict what kinds of photo IDs can be used (New Hampshire H.B. 429, Mississippi H.B. 543), and some would force voters to include a photocopy of their ID with their absentee ballots (Texas S.B. 1). Requiring voter ID (and particularly certain types of ID) is problematic because there are not enough opportunities for people to obtain IDs—lunch hour spent at the DMV, anyone?—and cost barriers make obtaining an ID unfeasible for many disenfranchised populations. This also ties in with the legislative efforts to reduce voter registration opportunities, whether that be election day registration or limiting or reducing automatic voter registration.

Lastly, some state legislatures have decided that amplifying voter purge practices is the way forward. The practice is already flawed (and usually ineffective and unnecessary), but the proposed legislation would expand the scale of extant purges or adopt procedures that would likely result in improper purges. Texas legislators have sent a bill to the governor that would add new criminal penalties to voting processes, enhance partisan poll-watching, and ban measures previously enacted to increase access to voting. New Hampshire has gone so far as to propose a bill that would violate the National Voter Registration Act.

Staying on our toes

Although some legislation has been proposed to expand access to voting, the backlash and restrictions are what anyone concerned with protecting the right to vote should be worried about. The proposed restrictions on voting would remove people from voter rolls, make it harder to vote in person by heightening ID requirements, erect further barriers to obtaining IDs, severely limit who can vote absentee, and add arbitrary hurdles to voting by mail generally. The individual right to vote is integral to securing and maintaining American democracy, and efforts to build barriers that would make it nearly impossible for American citizens to vote are plainly wrong. Preventing voter fraud is important, but using rhetoric about “election integrity” to justify disenfranchising certain populations is classist, racist, and morally repugnant, and that is without touching the constitutional and legal issues surrounding the matter. Already, the Democrat-controlled U.S. Congress is taking steps to prevent the voter suppression promulgated by this wave of state legislation. What Republicans who are worried about votes in the hands of marginalized communities do not realize is that it isn’t a matter of barriers and restrictive legislation, it’s a matter of time. Georgia was one of the first dominoes to fall, but it won’t be the last, especially with the federal government ready and willing to strengthen voting rights and access.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Archegos Capital Management and Family Office Regulation Reform

Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (D-NY), who has been at the vanguard of the movement to eradicate preferential treatment for the rich, may soon score a win for that cause. In July 2021, the congresswoman introduced H.R. 4620, the Family Office Regulation Act of 2021. The bill, if enacted, would curb the preferential treatment family offices enjoy under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Over the past year, events in the family office industry reveal the possible exploitation of these entities, the potential risks to the financial system, and the need for reform.

What are family offices and why are they on Rep. Ocasio Cortez’s mind? Family offices are a little-known type of investment management entity that manage the assets of wealthy families. Only the owning family members may be clients of family offices and these entities may not hold themselves out as investment advisers to the public. Wealthy families enjoy the family office model because it offers highly customized wealth management. Furthermore, and key to the issue addressed by H.R. 4620, family offices do not need to register as investment advisers with the Securities Exchange Commission.

In March 2021, Archegos Capital Management, a family office managing $20 billion in assets suffered a dramatic collapse causing several banks, primarily Credit Suisse and Nomura, to lose billions of dollars. The failure of Archegos has focused the attention of regulators, legislators and financial industry participants on family offices, which remain largely unregulated.

In March 2021, Archegos Capital Management, a family office managing $20 billion in assets suffered a dramatic collapse causing several banks, primarily Credit Suisse and Nomura, to lose billions of dollars. The failure of Archegos has focused the attention of regulators, legislators and financial industry participants on family offices, which remain largely unregulated.

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 defines an investment adviser as “any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others . . . as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities . . . .” Most investment management firms fall squarely within this definition. As a result, they are subject to the requirements and prohibitions imposed by the Advisers Act, including registration with and periodic examinations by the SEC. Family offices, like other private fund advisers of hedge funds, private equity funds, and venture capital funds, historically were exempt from registering with the SEC because these funds were not generally available to ordinary investors; the Advisers Act focus for protection. Private advisers could avoid registration with the SEC by accepting only accredited investors (high net worth individuals, investment professionals, or institutions), did not market their securities to the public, and constrained the resale of their securities. Although the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act repealed the private adviser exemption, it not only preserved favorable treatment for family offices, but it also directed the SEC to define “family office” and exclude it from the definition of the Advisers Act. The rationale for this carveout, the Family Office Rule, ostensibly was a recognition that “the Advisers Act is not designed to regulate the interactions of family members, and registration would unnecessarily intrude on the privacy of the family involved.” In reality, the Family Office Rule may have been the result of a successful lobbying effort by the family office industry.

The Family Office Rule has been tremendous boon to the family office industry. Family offices avoid the costly legal expenses associated with complying with the Advisers Act. Furthermore, family offices do not compromise their privacy by disclosing information about their investments to government regulators. Hedge fund investors have noticed the advantages family offices offer. Dozens of prominent hedge fund investors converted their funds into family offices. The family office model allows investors to take on more risk by abandoning cautious outside investors and avoiding any reporting requirements that may reveal risky investment strategies to regulators. Hedge fund investors have shown a willingness to return client funds to manage their own personal wealth under the family office model. The influx of former hedge fund investors into the family office space has led to more high-risk investments made by these entities.

No person typifies the recent transformation of the family office industry better than Bill Hwang, the founder of Archegos. Hwang is a former hedge fund manager who amassed a personal fortune. After an insider trading scandal earned him a five-year ban on managing client funds, Hwang founded Archegos which he incepted with $200 million of his own money. From 2013 to 2021, Hwang deployed a highly successful, but equally risky investment strategy. He invested his entire portfolio in a handful of stocks. He used leverage, in the form of total return swaps, to magnify his exposure to those stocks. Total return swaps are derivative contracts in which banks agree to own assets for an investor and make payments to the investor based on the asset’s performance in exchange for fixed payments made by the investor. Investors do not need the funds to pay for the actual assets; they only need money to pay the bank the fixed payments determined by the contract. If the asset’s performance suffers, the investor must further compensate the bank for the negative returns. If the bank fears that the investor is unable to meet its obligations under a total return swap, the bank may sell the underlying asset. In March 2021 the share price of ViacomCBS, a key Archegos investment, dipped sharply. Two of the banks holding total return swap agreements with Hwang knew that this imperiled Archegos’ portfolio and began selling the stocks, driving down the value of the Archegos portfolio. Other banks followed suit, but some acted too slowly. The diminished value of Archegos’ portfolio left Hwang unable to pay the banks what he owed, causing billions of dollars in losses.

No person typifies the recent transformation of the family office industry better than Bill Hwang, the founder of Archegos. Hwang is a former hedge fund manager who amassed a personal fortune. After an insider trading scandal earned him a five-year ban on managing client funds, Hwang founded Archegos which he incepted with $200 million of his own money. From 2013 to 2021, Hwang deployed a highly successful, but equally risky investment strategy. He invested his entire portfolio in a handful of stocks. He used leverage, in the form of total return swaps, to magnify his exposure to those stocks. Total return swaps are derivative contracts in which banks agree to own assets for an investor and make payments to the investor based on the asset’s performance in exchange for fixed payments made by the investor. Investors do not need the funds to pay for the actual assets; they only need money to pay the bank the fixed payments determined by the contract. If the asset’s performance suffers, the investor must further compensate the bank for the negative returns. If the bank fears that the investor is unable to meet its obligations under a total return swap, the bank may sell the underlying asset. In March 2021 the share price of ViacomCBS, a key Archegos investment, dipped sharply. Two of the banks holding total return swap agreements with Hwang knew that this imperiled Archegos’ portfolio and began selling the stocks, driving down the value of the Archegos portfolio. Other banks followed suit, but some acted too slowly. The diminished value of Archegos’ portfolio left Hwang unable to pay the banks what he owed, causing billions of dollars in losses.

When the dust settled, it became clear that Hwang had obfuscated an extremely risky trading strategy not just from his financial system counterparts, but also from virtually all financial regulators. Archegos’ failure was reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis, where losses at highly leveraged hedge funds contributed to the crisis and the failure of systematically important financial institutions. The 2008 financial crisis spurred reform aimed at improving regulators’ insight into private fund activity. Some now feel that the Archegos saga demonstrates that regulators are not able to assess the systemic risk that family offices impose on the financial system. Legislators like Rep. Ocasio Cortez have stepped forward to address that problem.

H.R. 4620 limits the Family Office Rule to funds with $750 million or less in assets under management that are not subject to final orders for fraud, manipulation or deceit. The bill also excludes family offices that have less than $750 million in highly leveraged assets and those that the SEC determines engage in risky activities. If the bill becomes law, many family offices would be required to file an annual Form ADV, the registration statement that registered investment advisers complete each year.

H.R. 4620 limits the Family Office Rule to funds with $750 million or less in assets under management that are not subject to final orders for fraud, manipulation or deceit. The bill also excludes family offices that have less than $750 million in highly leveraged assets and those that the SEC determines engage in risky activities. If the bill becomes law, many family offices would be required to file an annual Form ADV, the registration statement that registered investment advisers complete each year.

H.R. 4620 is a well-crafted strategy to subsume family offices into the existing regulatory environment for investment advisers. It aligns the treatment of most family offices with the treatment applied to most investment advisers. By filing Form ADV, the SEC will have information about family offices including the identity of controlling persons, how operations are financed, the disciplinary history employees, and information about the private funds managed. The SEC uses the information on ADVs to develop risk profiles. It will conduct examinations on those family offices whose ADVs suggest misconduct or raise some other red flag. While no piece of legislation will ever completely eradicate wild risk-taking from the investment world, this measure could bring such activity in the family office industry out of the shadows and give regulators a fighting chance of addressing it before its negative effects are suffered throughout the financial system.

Michael Murphy anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Michael Murphy anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Decriminalize Everything? Oregon’s New Drug Laws

In November 2020, Oregon voters overwhelmingly decided to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of almost all hard drugs. Measure 110 went into effect on February 1, 2021. The legislation took a groundbreaking, albeit controversial step by reclassifying the possession of hard drugs. Offenses that were formally criminal misdemeanors, subjecting citizens to arrest, fines, and jail time, are now mere civil violations, subject only to a $100 civil citation, which can be avoided by participation in health assessments.

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

- 1 gram of heroin;

- 1 gram of MDMA;

- 2 grams of methamphetamine;

- 40 units of LSD;

- 12 grams of psilocybin;

- 40 units of methadone;

- 40 pills of oxycodone; and

- 2 grams of cocaine.

The measure further reduces the charge from a felony to a misdemeanor for simple possession of substances where the amount is:

- 1-3 grams of heroin;

- 1-4 grams of MDMA;

- 2-8 grams of methamphetamine; and

- 2-8 grams of cocaine.

As noted by Oregon State Policy Capt. Timothy Fox, “possession of larger amounts of drugs, manufacturing and distribution are still crimes.”

The law was predicted to have a drastic impact on yearly convictions for possession of controlled substances. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission estimated yearly convictions would decrease by a staggering 90.7%. The legislation comes approximately 50 years after President Richard Nixon famously declared his War on Drugs. While the drug war has been criticized as a racist, inhumane failure, Oregon’s recent legislation marks a significant, perhaps radical step towards restructuring the deeply flawed systems instituted over the past half century. This article will first explore the main arguments on either side of the debate regarding the wisdom and efficacy of Measure 110. Later, it will discuss some cautious conclusions and the broader implications of Measure 110 and how it might fit within the larger, national public debate regarding drug decriminalization.

The Promise

Proponents of Measure 110 see it as a much overdue remedial measure to a disastrous drug war that has done far more harm than good. Kassandra Frederique, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”), remarked on its passing, “Today, the first domino of our cruel and inhuman war on drugs has fallen, setting off what we expect to be a cascade of other efforts centering health over criminalization.” Supporters highlight the wisdom of shifting from a drug policy model that focuses on punishment, incarceration and criminalization to a more progressive model that sees drug use and addiction as a disease to be treated rather than a crime to be punished. From this perspective, substance use is better addressed by providing access to physical and mental healthcare and removing the stigmatization and obstacles that traditionally accompany drug charges such as the difficulty landing jobs and finding housing. “Criminalization keeps people in the shadows. It keeps people from seeking out help, from telling their doctors, from telling their family members that they have a problem,” says Mike Schmidt, district attorney for Oregon’s most populated county.