Voter Suppression Laws in the Wake of Democratic Control of the Presidency and Senate

Georgia gained national attention in the 2020 election when the predominantly red state broke its 24-year streak of voting for Republican candidates in U.S. Presidential Elections. It went on to make history in early 2021 when the electorate flipped the U.S. Senate and elected Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to the U.S. Senate, respectively the first Black and Jewish Senators from Georgia.

A large part of this victory both in the White House and the Senate is attributed to Stacey Abrams, the Democrat gubernatorial candidate in Georgia’s 2018 election. Abrams’ gubernatorial campaign was unsuccessful, in large part because of voter suppression, but rather than wallow in defeat and fade into the background, Abrams became a loud, powerful voice—speaking against voter suppression and registering hundreds of thousands of voters in Georgia.

And now Republicans—in Georgia and across the nation—formally responded, pushing a huge new wave of voter suppression tactics in the name of “election integrity.”

S.B. 71

Among other legislation, Republicans in the Georgia Senate have proposed S.B. 71, which would change the definition of absentee voter entirely. For the past 15 years or so, Georgia has been a “no excuse needed” absentee voting state, but this bill would require people who wish to vote absentee to

- Be physically absent from their precinct during the election;

- Be able to perform any of the “official acts or duties” connected to the election;

- Be absent because of physical disability or because you’re required to give constant care to someone who is disabled;

- Be observing a religious holiday;

- Be required to remain on duty for the “protection of the health, life, or safety of the public”; or

- Be at least 65-years-old.

These extremely limited exceptions would put even more emphasis on the luxury and privilege of time. Many people cannot take an hour (or more) out of their daily schedules—balancing child care, housing matters, and work among the other minutiae of modern life—to go to the polls. The oft-used argument to that is “well, there are plenty of precincts where you can get in and out in 10 minutes.” And while that may be accurate, the problem is inherent in the argument itself: that it isn’t true of every precinct; and issues with fewer voting machines, voter purges, and, therefore, long waits tend to disproportionately affect liberal-voting communities in Republican controlled states.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

Other Voter Suppression Legislation

Throughout the nation, state legislatures have begun putting forth bills that would restrict voting access—in fact, over four times more legislation that would restrict voting has been proposed than was proposed this time last year.

Georgia is not alone in limiting absentee voting. Nine other states have proposed bills that would either eliminate “no excuse” voting or crack down on the requirements for absentee voting where “excuse” voting is already in place. Other bills make it more difficult to obtain ballots in the first place by changing the laws concerning permanent early voter lists. Some measures go so far as to eliminate permanent early voter lists (which would force people now on those lists to take more steps to vote every year; Arizona S.B. 1678, Hawaii H.B. 1262, and New Jersey S.B. 3391) while others would reduce how long someone remains on the permanent absentee voter list (Florida S.B. 90).

Other proposals concern stricter voter ID requirements—a long contentious aspect of voter suppression. States that do not currently require photo IDs to vote are considering requiring them in the future, other states are trying to restrict what kinds of photo IDs can be used (New Hampshire H.B. 429, Mississippi H.B. 543), and some would force voters to include a photocopy of their ID with their absentee ballots (Texas S.B. 1). Requiring voter ID (and particularly certain types of ID) is problematic because there are not enough opportunities for people to obtain IDs—lunch hour spent at the DMV, anyone?—and cost barriers make obtaining an ID unfeasible for many disenfranchised populations. This also ties in with the legislative efforts to reduce voter registration opportunities, whether that be election day registration or limiting or reducing automatic voter registration.

Lastly, some state legislatures have decided that amplifying voter purge practices is the way forward. The practice is already flawed (and usually ineffective and unnecessary), but the proposed legislation would expand the scale of extant purges or adopt procedures that would likely result in improper purges. Texas legislators have sent a bill to the governor that would add new criminal penalties to voting processes, enhance partisan poll-watching, and ban measures previously enacted to increase access to voting. New Hampshire has gone so far as to propose a bill that would violate the National Voter Registration Act.

Staying on our toes

Although some legislation has been proposed to expand access to voting, the backlash and restrictions are what anyone concerned with protecting the right to vote should be worried about. The proposed restrictions on voting would remove people from voter rolls, make it harder to vote in person by heightening ID requirements, erect further barriers to obtaining IDs, severely limit who can vote absentee, and add arbitrary hurdles to voting by mail generally. The individual right to vote is integral to securing and maintaining American democracy, and efforts to build barriers that would make it nearly impossible for American citizens to vote are plainly wrong. Preventing voter fraud is important, but using rhetoric about “election integrity” to justify disenfranchising certain populations is classist, racist, and morally repugnant, and that is without touching the constitutional and legal issues surrounding the matter. Already, the Democrat-controlled U.S. Congress is taking steps to prevent the voter suppression promulgated by this wave of state legislation. What Republicans who are worried about votes in the hands of marginalized communities do not realize is that it isn’t a matter of barriers and restrictive legislation, it’s a matter of time. Georgia was one of the first dominoes to fall, but it won’t be the last, especially with the federal government ready and willing to strengthen voting rights and access.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Archegos Capital Management and Family Office Regulation Reform

Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (D-NY), who has been at the vanguard of the movement to eradicate preferential treatment for the rich, may soon score a win for that cause. In July 2021, the congresswoman introduced H.R. 4620, the Family Office Regulation Act of 2021. The bill, if enacted, would curb the preferential treatment family offices enjoy under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Over the past year, events in the family office industry reveal the possible exploitation of these entities, the potential risks to the financial system, and the need for reform.

What are family offices and why are they on Rep. Ocasio Cortez’s mind? Family offices are a little-known type of investment management entity that manage the assets of wealthy families. Only the owning family members may be clients of family offices and these entities may not hold themselves out as investment advisers to the public. Wealthy families enjoy the family office model because it offers highly customized wealth management. Furthermore, and key to the issue addressed by H.R. 4620, family offices do not need to register as investment advisers with the Securities Exchange Commission.

In March 2021, Archegos Capital Management, a family office managing $20 billion in assets suffered a dramatic collapse causing several banks, primarily Credit Suisse and Nomura, to lose billions of dollars. The failure of Archegos has focused the attention of regulators, legislators and financial industry participants on family offices, which remain largely unregulated.

In March 2021, Archegos Capital Management, a family office managing $20 billion in assets suffered a dramatic collapse causing several banks, primarily Credit Suisse and Nomura, to lose billions of dollars. The failure of Archegos has focused the attention of regulators, legislators and financial industry participants on family offices, which remain largely unregulated.

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940 defines an investment adviser as “any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others . . . as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities . . . .” Most investment management firms fall squarely within this definition. As a result, they are subject to the requirements and prohibitions imposed by the Advisers Act, including registration with and periodic examinations by the SEC. Family offices, like other private fund advisers of hedge funds, private equity funds, and venture capital funds, historically were exempt from registering with the SEC because these funds were not generally available to ordinary investors; the Advisers Act focus for protection. Private advisers could avoid registration with the SEC by accepting only accredited investors (high net worth individuals, investment professionals, or institutions), did not market their securities to the public, and constrained the resale of their securities. Although the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act repealed the private adviser exemption, it not only preserved favorable treatment for family offices, but it also directed the SEC to define “family office” and exclude it from the definition of the Advisers Act. The rationale for this carveout, the Family Office Rule, ostensibly was a recognition that “the Advisers Act is not designed to regulate the interactions of family members, and registration would unnecessarily intrude on the privacy of the family involved.” In reality, the Family Office Rule may have been the result of a successful lobbying effort by the family office industry.

The Family Office Rule has been tremendous boon to the family office industry. Family offices avoid the costly legal expenses associated with complying with the Advisers Act. Furthermore, family offices do not compromise their privacy by disclosing information about their investments to government regulators. Hedge fund investors have noticed the advantages family offices offer. Dozens of prominent hedge fund investors converted their funds into family offices. The family office model allows investors to take on more risk by abandoning cautious outside investors and avoiding any reporting requirements that may reveal risky investment strategies to regulators. Hedge fund investors have shown a willingness to return client funds to manage their own personal wealth under the family office model. The influx of former hedge fund investors into the family office space has led to more high-risk investments made by these entities.

No person typifies the recent transformation of the family office industry better than Bill Hwang, the founder of Archegos. Hwang is a former hedge fund manager who amassed a personal fortune. After an insider trading scandal earned him a five-year ban on managing client funds, Hwang founded Archegos which he incepted with $200 million of his own money. From 2013 to 2021, Hwang deployed a highly successful, but equally risky investment strategy. He invested his entire portfolio in a handful of stocks. He used leverage, in the form of total return swaps, to magnify his exposure to those stocks. Total return swaps are derivative contracts in which banks agree to own assets for an investor and make payments to the investor based on the asset’s performance in exchange for fixed payments made by the investor. Investors do not need the funds to pay for the actual assets; they only need money to pay the bank the fixed payments determined by the contract. If the asset’s performance suffers, the investor must further compensate the bank for the negative returns. If the bank fears that the investor is unable to meet its obligations under a total return swap, the bank may sell the underlying asset. In March 2021 the share price of ViacomCBS, a key Archegos investment, dipped sharply. Two of the banks holding total return swap agreements with Hwang knew that this imperiled Archegos’ portfolio and began selling the stocks, driving down the value of the Archegos portfolio. Other banks followed suit, but some acted too slowly. The diminished value of Archegos’ portfolio left Hwang unable to pay the banks what he owed, causing billions of dollars in losses.

No person typifies the recent transformation of the family office industry better than Bill Hwang, the founder of Archegos. Hwang is a former hedge fund manager who amassed a personal fortune. After an insider trading scandal earned him a five-year ban on managing client funds, Hwang founded Archegos which he incepted with $200 million of his own money. From 2013 to 2021, Hwang deployed a highly successful, but equally risky investment strategy. He invested his entire portfolio in a handful of stocks. He used leverage, in the form of total return swaps, to magnify his exposure to those stocks. Total return swaps are derivative contracts in which banks agree to own assets for an investor and make payments to the investor based on the asset’s performance in exchange for fixed payments made by the investor. Investors do not need the funds to pay for the actual assets; they only need money to pay the bank the fixed payments determined by the contract. If the asset’s performance suffers, the investor must further compensate the bank for the negative returns. If the bank fears that the investor is unable to meet its obligations under a total return swap, the bank may sell the underlying asset. In March 2021 the share price of ViacomCBS, a key Archegos investment, dipped sharply. Two of the banks holding total return swap agreements with Hwang knew that this imperiled Archegos’ portfolio and began selling the stocks, driving down the value of the Archegos portfolio. Other banks followed suit, but some acted too slowly. The diminished value of Archegos’ portfolio left Hwang unable to pay the banks what he owed, causing billions of dollars in losses.

When the dust settled, it became clear that Hwang had obfuscated an extremely risky trading strategy not just from his financial system counterparts, but also from virtually all financial regulators. Archegos’ failure was reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis, where losses at highly leveraged hedge funds contributed to the crisis and the failure of systematically important financial institutions. The 2008 financial crisis spurred reform aimed at improving regulators’ insight into private fund activity. Some now feel that the Archegos saga demonstrates that regulators are not able to assess the systemic risk that family offices impose on the financial system. Legislators like Rep. Ocasio Cortez have stepped forward to address that problem.

H.R. 4620 limits the Family Office Rule to funds with $750 million or less in assets under management that are not subject to final orders for fraud, manipulation or deceit. The bill also excludes family offices that have less than $750 million in highly leveraged assets and those that the SEC determines engage in risky activities. If the bill becomes law, many family offices would be required to file an annual Form ADV, the registration statement that registered investment advisers complete each year.

H.R. 4620 limits the Family Office Rule to funds with $750 million or less in assets under management that are not subject to final orders for fraud, manipulation or deceit. The bill also excludes family offices that have less than $750 million in highly leveraged assets and those that the SEC determines engage in risky activities. If the bill becomes law, many family offices would be required to file an annual Form ADV, the registration statement that registered investment advisers complete each year.

H.R. 4620 is a well-crafted strategy to subsume family offices into the existing regulatory environment for investment advisers. It aligns the treatment of most family offices with the treatment applied to most investment advisers. By filing Form ADV, the SEC will have information about family offices including the identity of controlling persons, how operations are financed, the disciplinary history employees, and information about the private funds managed. The SEC uses the information on ADVs to develop risk profiles. It will conduct examinations on those family offices whose ADVs suggest misconduct or raise some other red flag. While no piece of legislation will ever completely eradicate wild risk-taking from the investment world, this measure could bring such activity in the family office industry out of the shadows and give regulators a fighting chance of addressing it before its negative effects are suffered throughout the financial system.

Michael Murphy anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Michael Murphy anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Decriminalize Everything? Oregon’s New Drug Laws

In November 2020, Oregon voters overwhelmingly decided to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of almost all hard drugs. Measure 110 went into effect on February 1, 2021. The legislation took a groundbreaking, albeit controversial step by reclassifying the possession of hard drugs. Offenses that were formally criminal misdemeanors, subjecting citizens to arrest, fines, and jail time, are now mere civil violations, subject only to a $100 civil citation, which can be avoided by participation in health assessments.

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

- 1 gram of heroin;

- 1 gram of MDMA;

- 2 grams of methamphetamine;

- 40 units of LSD;

- 12 grams of psilocybin;

- 40 units of methadone;

- 40 pills of oxycodone; and

- 2 grams of cocaine.

The measure further reduces the charge from a felony to a misdemeanor for simple possession of substances where the amount is:

- 1-3 grams of heroin;

- 1-4 grams of MDMA;

- 2-8 grams of methamphetamine; and

- 2-8 grams of cocaine.

As noted by Oregon State Policy Capt. Timothy Fox, “possession of larger amounts of drugs, manufacturing and distribution are still crimes.”

The law was predicted to have a drastic impact on yearly convictions for possession of controlled substances. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission estimated yearly convictions would decrease by a staggering 90.7%. The legislation comes approximately 50 years after President Richard Nixon famously declared his War on Drugs. While the drug war has been criticized as a racist, inhumane failure, Oregon’s recent legislation marks a significant, perhaps radical step towards restructuring the deeply flawed systems instituted over the past half century. This article will first explore the main arguments on either side of the debate regarding the wisdom and efficacy of Measure 110. Later, it will discuss some cautious conclusions and the broader implications of Measure 110 and how it might fit within the larger, national public debate regarding drug decriminalization.

The Promise

Proponents of Measure 110 see it as a much overdue remedial measure to a disastrous drug war that has done far more harm than good. Kassandra Frederique, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”), remarked on its passing, “Today, the first domino of our cruel and inhuman war on drugs has fallen, setting off what we expect to be a cascade of other efforts centering health over criminalization.” Supporters highlight the wisdom of shifting from a drug policy model that focuses on punishment, incarceration and criminalization to a more progressive model that sees drug use and addiction as a disease to be treated rather than a crime to be punished. From this perspective, substance use is better addressed by providing access to physical and mental healthcare and removing the stigmatization and obstacles that traditionally accompany drug charges such as the difficulty landing jobs and finding housing. “Criminalization keeps people in the shadows. It keeps people from seeking out help, from telling their doctors, from telling their family members that they have a problem,” says Mike Schmidt, district attorney for Oregon’s most populated county.

A key provision of Measure 110 earmarks a portion of cannabis tax revenues for improving and expanding the state’s treatment system, along with drug safety education and services. To date, Oregon has generated hundreds of millions of dollars for this purpose, distributed to at least 70 different organizations in 26 different counties, aimed primarily at helping providers expand services for people with low incomes and without insurance. This kind of investment is clearly a necessary part of shifting from a model oriented around the criminal justice system to a model oriented around healthcare. In addition, proponents of Measure 110 emphasize that decriminalization will ease racial disparities in drug arrests. For example, African American Oregonians are 2.5 times as likely to be convicted of a possession felony as whites. Without delving into the reasons behind this disparity, by reducing possession convictions overall decriminalization will reduce the negative effects on minority communities. Indeed, according to Theshia Naidoo, managing director for legal affairs at DPA, although the “information is not fully available yet . . . from the data we can see, there have been no drug possession arrests in the state since the decriminalization took effect.”

One major area of concern is implementation. Detractors question whether Oregon’s treatment system has the resources and functionality required to support such a fundamental shift away from the criminal justice system as the primary model for addressing drug use and executing drug policy. Are the resources provided by Measure 110 adequate to handle a corresponding substantial influx of people seeking treatment? Unfortunately, It is likely still too early to tell; but shifting from the criminal justice to the health care system is undoubtedly not going to happen overnight.

Relatedly, critics question whether a civil citation akin to a parking ticket will provide the adequate impetus and resources for users to seek help. Mike Marshall, co-founder and director of Oregon Recovers, worries that “the only way to get access to recovery services is by being arrested or interacting with the criminal justice system. Measure 110 took away that pathway.” Perhaps the threat of the criminal justice system provides users with the necessary motivation to seek treatment and the threat of a citation and potential fine is lacking in some critical respect. Decriminalization may ultimately limit access to treatment as fewer offenders are pushed into court-ordered programs. Decriminalization advocates counter that the criminal justice system’s pathway to treatment is flawed, biased and ineffectual, and point out that “on average a huge percentage [approximately 70 to 80 percent in Multnomah county] of those convicted of drug possession in the state were rearrested within three years.” Regardless, there is shockingly little data to determine what programs work best and no agreed upon set of metrics or benchmarks to judge program efficacy, either in Oregon or nationally.

The Verdict

Unfortunately, it’s likely too early to fairly assess whether Oregon’s remarkable drug policy transformation can be deemed a success. Part of this is because the transformation is still underway. Supporters of decriminalization point to Portugal as a reform model, which took more than two years to transition from a system centered around the criminal justice system to a healthcare model. Covid-19 is a another complication; Oregon’s detox clinics, recovery-focused nonprofits, and impatient facilities have been battered by the pandemic and related workforce shortages.

Nonetheless, Oregon’s bold efforts have seemingly inspired state level decriminalization efforts across the country as lawmakers in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont have all proposed similar decriminalization bills this year. The takeaway seems to be that decriminalization is a wise policy so long as recovery services are widely available. As Reginald Richardson, director of Oregon’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission, put it, “the use of criminal justice becomes a necessary proxy when you don’t have effective behavioral health services.” Overall, this kind of major shift in policy is daunting and will always involve overcoming unforeseen challenges, although hopefully not always to the extent of a global pandemic. Still, the Nixon-era drug policies has largely been an abject failure, and states like Oregon ought to be commended for trying, however imperfectly, to improve their approach.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Emergency Opportunity: Legislating Away Roe v. Wade During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

At the outset of the pandemic, many states banned “nonessential” medical procedures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and preserve PPE. However, several states took the opportunity to classify abortion as a “nonessential” procedure, making the surgery inaccessible. At the same time, the FDA deregulated the requirements for in-person prescription of many drugs, even opioids, but continued to heavily regulate medication related to abortion.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

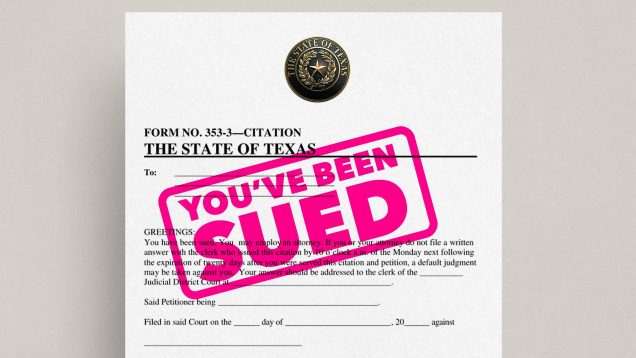

While the FDA was in legal battles over the requirements for medication abortion, conservative states began launching and defending legislation that restricted the right to a surgical abortion. During the 2021 session the Texas Legislature enacted the Texas Heartbeat Act, which bans abortion at the first sign of fetal heartbeat, which can be as early as 6 weeks. As BU Law and School of Public Health Professor Nicole Huberfeld pointed out, many women do not know they are pregnant within 6 weeks, and a “heartbeat” may mean no more than detecting an electrical pulse.

The key feature that has made Act a standout among anti-abortion bills is the citizen suit provision. The Act allows,

“any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local government entity in [the] state, may bring a civil action against any person who…performs or induces an abortion” or “aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.”

Enforcement is exclusively through private civil actions, a self-protecting mechanism that has been thought provoking for both the courts and the public. The lack of government enforcement leads many people to believe that there was no one to sue in order to challenge the legislation through judicial review. While the legislators may have thought this workaround clever, the Court recently held in Whole Women's Health v. Jackson that abortion providers may challenge the law by suing licensing officials. Still, the limited opportunity for judicial review may leave future constitutional rights vulnerable to this same evasive structure employed by the Texas legislation.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Just before announcing its limited decision allowing judicial review of the Heartbeat Act, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs centered around pre-pandemic Mississippi anti-abortion legislation, known as the “Gestational Age Act.” This Act directly confronts the holding of Planned Parenthood v. Casey by banning abortion after 15 weeks. It lacks the workaround that Texas employed but may nevertheless garner enough support from the Supreme Court to overturn the precedent from the Roe v. Wade line of cases. While Justice Roberts seemed inclined to uphold Roe but push back the line of imposing an undue burden to 15 weeks, other justices see the challenge as a call for an all-or nothing reversal of Roe. Overturning Roe would mean a complete change in the law surrounding abortion not just because of overturning common law precedent, but also because many states have drafted trigger laws, that specify that if Roe is overturned, abortion is automatically illegal in the state.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

U.S. Citizenship and Justice for American Samoa

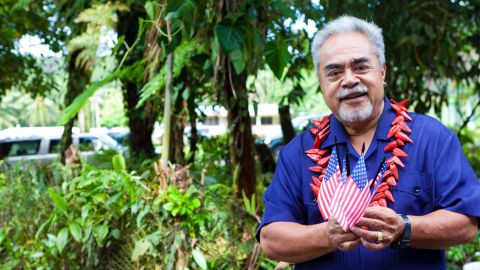

On March 16, 2021, Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen, a non-voting congressional delegate for American Samoa, introduced House Resolution 1941 - To amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to waive certain naturalization requirements for United States nationals, and for other purposes. This bill would allow eligible U.S. Nationals in Outlying Possessions to become citizens upon establishing residence and physical presence in those territories. It would also waive certain other naturalization requirements for non-citizen nationals, who currently need to become a resident of a U.S. state to qualify. The mere existence of this bill raises questions about the nature of the relationship between America and its “Outlying Possessions” like American Samoa. Why are the inhabitants of Tutuila, the Manuʻa Islands, Rose Atoll, and Swains Island called “American” Samoans when they are not born with equal legal status to other Americans?

On March 16, 2021, Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen, a non-voting congressional delegate for American Samoa, introduced House Resolution 1941 - To amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to waive certain naturalization requirements for United States nationals, and for other purposes. This bill would allow eligible U.S. Nationals in Outlying Possessions to become citizens upon establishing residence and physical presence in those territories. It would also waive certain other naturalization requirements for non-citizen nationals, who currently need to become a resident of a U.S. state to qualify. The mere existence of this bill raises questions about the nature of the relationship between America and its “Outlying Possessions” like American Samoa. Why are the inhabitants of Tutuila, the Manuʻa Islands, Rose Atoll, and Swains Island called “American” Samoans when they are not born with equal legal status to other Americans?

In 1900, the United States and the German Empire unceremoniously partitioned Samoa between themselves. Neither had conquered their respective portion from one another, the prior British claimants, or even the native population. By the dawn of the 20th Century, apparently, western dominion was such a foregone conclusion that neither empire bothered to do much actual colonizing. The U.S., the Kaiserreich, and the British Empire decided the fate of the Samoans in a Washington D.C. conference overseen by Oscar II, King of Sweden and Norway. No one invited any Samoans. The U.S. still claims sovereignty over its gains from this treaty. These five main islands (and two atolls) now constitute the unincorporated, unorganized territory of the United States known as American Samoa.

The United States possesses 16 territories, but only 5 are home to permanent populations. These are American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Supreme Court decided the unincorporated status of these territories in the 1901 Insular Cases, summarized by Stacey Plaskett of the Atlantic:

In a series of highly fractured and controversial decisions known collectively as the Insular Cases, the Supreme Court invented an unprecedented new category of “unincorporated” territories, which were not on a path to statehood and whose residents could be denied even basic constitutional rights. Which territories the Court determined were “unincorporated” turned largely on the justices’ view of the people who lived there—people they labeled “half-civilized,” “savage,” “alien races,” and “ignorant and lawless.”

While the other 4 unincorporated territories face legal challenges, all except American Samoa are organized. The full U.S. constitution does not apply in organized territories, and their congressional delegates are nonvoting. However, residents of organized territories are at least American citizens. Unique among permanently populated U.S. territories, American Samoa’s people are not citizens. At birth, they receive the lesser status of non-citizen U.S. National. U.S. Nationals cannot vote in elections held in the 50 states. People born in other territories, like Puerto Rico, are citizens and can vote in these elections. American Samoa is the only permanently inhabited territory of the U.S. whose people are not American citizens.

Lesser voting rights are not the only difference between American citizens and nationals. Despite claims from sources such as the National Conference of State Legislatures that “There’s not much difference between the two designations,” American Samoans face unique legal challenges as described by Temple Law Professor Tom C.W. Lin:

However, unlike the other Territories, where Congress conferred citizenship to the people of each Territory, Congress enacted no such enabling act for the people of American Samoa. Accordingly, American Samoans are non-citizen nationals of the United States. They reside in an “interstitial” space in law and fact, with some, but not all, of the rights and privileges that accompany citizenship. As non-citizen nationals, American Samoans are ineligible for many government jobs, benefits, and privileges that are afforded only to citizens of the United States.

To be a second-class citizen, one has to at least be a citizen. In the current legal framework, U.S. national Samoans are second-class Americans.

This legal status is not simply a forgotten artifact of gilded-age American imperialism. In 2012 Leneuoti Tuaua, prohibited from police work in California because of his non-citizen national status, filed suit against the State Department and the Obama administration. His counsel argued that the citizenship clause of the 14th amendment (“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States”) guaranteed those born in American Samoa citizenship without the need for approval by Congress. Citing the 1901 Insular Cases, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled 3-0 that only Congress could grant citizenship to non-citizen nationals. The Supreme Court denied certiorari. In 2019, John Fitisemanu challenged the “federal policy [requirement] that his U.S. passport include a disclaimer in all capital letters that ‘THE BEARER IS A UNITED STATES NATIONAL AND NOT A UNITED STATES CITIZEN.’” His counsel too argued that the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment guarantees birthright citizenship to American Samoans. A Utah district court agreed with Fitisemanu, but the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed. The Fitisemanu plaintiffs sought a sought a rehearing en banc but the court denied the motion in December, 2021.

It is unlikely the current Supreme Court will grant certiorari. The Court has made its position clear: only Congress can alter the status of those born in unorganized territories. Another complication arises in that blanket citizenship does not see universal support among American Samoans. Along with religious concerns, some believe an organizing act would upset traditional land ownership. The islands’ government employs Samoan ancestry requirements to keep land in the hands of native families. These requirements would likely be held unconstitutional if all American Samoans were made citizens. This could potentially lead to wealthy outsiders and corporations buying out locals, threatening the American Samoans’ cultural and economic way of life. As such, Delegate Radewagen’s H.R. 1941 represents a worthy compromise. It would greatly reduce barriers to citizenship for U.S. National Samoans, while also preserving a legal system that allows them to carry on their traditional way of life. Delegate Radewagen’s proposed bill was sent to the House Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship in May 2021. Congress should pass this legislation to give American Samoans back the individual right to self-determination denied to them over 100 years ago.

James Hallisey anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

James Hallisey anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Time To Bring Back Happy Hour To Massachusetts?

This session the Massachusetts Legislature considered “An Act restoring happy hour to the commonwealth" SB.169 at the request of a group of Boston College Law School students. The bill would allow restaurants and bars to discount alcoholic beverages during specified times if drink prices are not changed during the happy hour; the happy hour does not take place after 10 pm; and notice of the happy hour is posted on the premises or website at least three days in advance.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

The 38-year effort against drunk driving has had a significant effect: by 2019 there were 10,142 drunk driving fatalities representing 28% of total traffic deaths. Today, AAA ranks Massachusetts first among all states for having the least severe drunk driving problem. However, it is unclear that happy hour restrictions contributed to this downward trend. For example, in 2015 Illinois legalized happy hours after a 26 year ban. According to Department of Transportation data, during 2014, the last year that happy hour was outlawed in Illinois, there were 353 alcohol-related traffic deaths—38% of all traffic fatalities. In 2019 there were 368 alcohol-related traffic deaths—36% of traffic fatalities. It appears doing away with the happy hour ban had little to no effect on alcohol impaired traffic deaths in the state. Other drunk driving measures such as the 21 year-old minimum drinking age, strict enforcement of drunk driving laws, and changing youth attitudes and behaviors surrounding drunk driving have played the largest role in the reduction in traffic deaths nationally. Still, a 2014 study found that college students greatly increased alcohol consumption during promotions and happy hours that decreased overall prices.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

The bill's findings and purposes section lists both the law’s ineffectiveness and economic factors for lifting the ban. The bill claims restoring happy hour “will support local businesses, shift patronage of bars and restaurants toward low-density hours, and benefit the public morale.”

Indeed, offering happy hour specials could help restaurants and bars boost sales during off-peak hours. In the time of Covid-19, these discounts and specials could mitigate the losses suffered during the pandemic. Joshua Lewin, a co-owner of a restaurant in Somerville and Boston argued that in the time of Covid happy hours bring in patrons during slow times of the day. Happy hours spread out the times in which people go to the restaurants as allow social distancing measures.

The proposal is also popular; a recent MassINC poll found 70% of people approved lifting the happy hour ban with only 9% strongly opposed. In addition, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (“MADD”), one of the strongest proponents for prohibiting happy hours, does not currently have an official stance on lifting the ban due to the advent of ride shares as a safeguards against drunk driving.

Allowing happy hours, however, faces significant opposition. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker is skeptical about the bill stating, “That law did not come about by accident. It came about because there was a sustained series of tragedies that involved both young and older people, in some terrible highway incidents, all of which track back to people who’d been over-served as a result of happy hours in a variety of places... I’d be hard-pressed to support changing it.”

While drunk driving and binge drinking are still a concern, drunk driving incidents have been on the decline over the last twenty years. Evidence suggests the Massachusetts prohibition of happy hour is outdated and ineffective for decreasing drunk driving. The Commonwealth should refocus its efforts to curb drunk driving through increased education and outreach programs along with tighter enforcement across the Commonwealth. Further, the Legislature should support legislation that will aid local business in any way that is practical; happy hours would give bars and restaurants a boost while helping to manage the flow of customers.

At any rate, the bill seems to be done for the session. The committee on Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure held a hearing on August 30, 2021, and in January 2022 sent the bill to a study order. Perhaps bars and restaurants will get some relief next year.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Time To Bring Back Happy Hour To Massachusetts?

This session the Massachusetts Legislature considered “An Act restoring happy hour to the commonwealth" SB.169 at the request of a group of Boston College Law School students. The bill would allow restaurants and bars to discount alcoholic beverages during specified times if drink prices are not changed during the happy hour; the happy hour does not take place after 10 pm; and notice of the happy hour is posted on the premises or website at least three days in advance.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

The 38-year effort against drunk driving has had a significant effect: by 2019 there were 10,142 drunk driving fatalities representing 28% of total traffic deaths. Today, AAA ranks Massachusetts first among all states for having the least severe drunk driving problem. However, it is unclear that happy hour restrictions contributed to this downward trend. For example, in 2015 Illinois legalized happy hours after a 26 year ban. According to Department of Transportation data, during 2014, the last year that happy hour was outlawed in Illinois, there were 353 alcohol-related traffic deaths—38% of all traffic fatalities. In 2019 there were 368 alcohol-related traffic deaths—36% of traffic fatalities. It appears doing away with the happy hour ban had little to no effect on alcohol impaired traffic deaths in the state. Other drunk driving measures such as the 21 year-old minimum drinking age, strict enforcement of drunk driving laws, and changing youth attitudes and behaviors surrounding drunk driving have played the largest role in the reduction in traffic deaths nationally. Still, a 2014 study found that college students greatly increased alcohol consumption during promotions and happy hours that decreased overall prices.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

The bill's findings and purposes section lists both the law’s ineffectiveness and economic factors for lifting the ban. The bill claims restoring happy hour “will support local businesses, shift patronage of bars and restaurants toward low-density hours, and benefit the public morale.”

Indeed, offering happy hour specials could help restaurants and bars boost sales during off-peak hours. In the time of Covid-19, these discounts and specials could mitigate the losses suffered during the pandemic. Joshua Lewin, a co-owner of a restaurant in Somerville and Boston argued that in the time of Covid happy hours bring in patrons during slow times of the day. Happy hours spread out the times in which people go to the restaurants as allow social distancing measures.

The proposal is also popular; a recent MassINC poll found 70% of people approved lifting the happy hour ban with only 9% strongly opposed. In addition, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (“MADD”), one of the strongest proponents for prohibiting happy hours, does not currently have an official stance on lifting the ban due to the advent of ride shares as a safeguards against drunk driving.

Allowing happy hours, however, faces significant opposition. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker is skeptical about the bill stating, “That law did not come about by accident. It came about because there was a sustained series of tragedies that involved both young and older people, in some terrible highway incidents, all of which track back to people who’d been over-served as a result of happy hours in a variety of places... I’d be hard-pressed to support changing it.”

While drunk driving and binge drinking are still a concern, drunk driving incidents have been on the decline over the last twenty years. Evidence suggests the Massachusetts prohibition of happy hour is outdated and ineffective for decreasing drunk driving. The Commonwealth should refocus its efforts to curb drunk driving through increased education and outreach programs along with tighter enforcement across the Commonwealth. Further, the Legislature should support legislation that will aid local business in any way that is practical; happy hours would give bars and restaurants a boost while helping to manage the flow of customers.

At any rate, the bill seems to be done for the session. The committee on Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure held a hearing on August 30, 2021, and in January 2022 sent the bill to a study order. Perhaps bars and restaurants will get some relief next year.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

US Policy Options for the No-Longer-Imaginary “Climate Refugee”

Rising sea levels, intense hurricanes, and dangerous flooding can cause sudden upheavals of individuals’ lives, making homes and entire areas uninhabitable for families or entire communities – sometimes, very suddenly. These “climate refugees” are often spoken in future terms, but they already exist; but the law in most places does not differentiate them from economic migrants who are seeking better jobs and living conditions. Governments, including the United States, have not redefined “refugees” to include those fleeing natural disaster, let alone climate change. The US should begin to rethink the concept of a refugee and put in place protections for those displaced by climate change.

The United Nations Refugee Convention set the definition for a refugee in 1951: someone outside their country of nationality or residence with a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, without the ability to seek protection in that country. Meeting this criteria entitles one to international protections such as non-refoulement: the practice of avoiding forcing refugees to return to countries where they have a high risk of persecution. The definition of a refugee rests wholly on persecution and makes no mention of natural disaster or climate-related factors.

The United Nations Refugee Convention set the definition for a refugee in 1951: someone outside their country of nationality or residence with a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, without the ability to seek protection in that country. Meeting this criteria entitles one to international protections such as non-refoulement: the practice of avoiding forcing refugees to return to countries where they have a high risk of persecution. The definition of a refugee rests wholly on persecution and makes no mention of natural disaster or climate-related factors.

One major complication that arises from climate refugee policy is that it is very unlikely that one dramatic event will push a family out of its home country. Rather, ongoing drought and extreme heat due to climate change result in unsustainable conditions in which families cannot make a living or gain meaningful quality of life. Drought may cause crops to fail, and a family may be forced to move somewhere where they need not depend on farming. This makes it difficult to distinguish between those relocating to new countries due to climate change versus pure economic factors, and these individuals are deemed “economic migrants” no matter the root cause of their flight.

Another factor is the lack of incentive for national governments to go beyond the minimum requirements for refugee status set long ago in the UN Convention, despite the worsening natural disasters and living conditions due to climate change. In 2018, a majority of the UN General Assembly affirmed the Global Compact on Refugees, which strives toward addressing the interactions between climate, environmental degradation, and disasters, and refugee movements; this is not a binding agreement that alters the original 1951 Convention, however, and it tends to focus only on instances where climate change causes conflict and persecution (entitling one to classic refugee protections) rather than threats to life due to rising temperatures.

Climate refugees already exist. Kiribati is a South Pacific island nation that is in danger of losing its entire landmass to rising sea levels due to climate change. In 2015, a Kiribati national, Ioane Teitiota, applied for “climate refugee” status with the New Zealand government, but this application was rejected and he was repatriated to Kiribati. A subsequent complaint with the UN resulted in the New Zealand government’s decision being upheld due to a lack of “imminent threat” to life, though the UN did acknowledge the serious threat to the human right to life posed by climate change. Since then, New Zealand has pledged to offer up to 100 special climate refugee visas to Pacific Islanders in the future.

Mr. Teitiota's application would have gotten the same result with almost any national government, including the United States. National governments have largely matched their own domestic refugee policy to the 1951 UN definition and have avoided changing it since the treaty was signed over 70 years ago. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Refugee Eligibility criteria match this definition, as does the legal definition of “refugee” in the Immigration and Nationality Act enacted in 1952. USCIS explicitly states that “If you are fleeing a civil war or natural disaster, you may not be eligible for resettlement under U.S. law. However, you may fall within the protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).” While “natural disaster” could mean climate change, the UHNCR states that “climate refugees” may only meet the definition of a refugee and be eligible for the associated protections when the “adverse effects of climate change interact with armed conflict and violence.” The UNHCR expressly does not endorse the term “climate refugee,” but rather “persons displaced in the context of disasters and climate change.” This leaves those displaced by climate change without refugee protection from either USCIS or UNHCR.

Congress has not frequently passed dramatic changes to U.S. immigration law; arguably, the last major legislation was during the Reagan administration in 1986, when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act making it a criminal offense for employers to hire undocumented migrants, offering legal status to some undocumented migrants who had been in the U.S. before 1982, and increasing security-based deterrence measures at the southern border. Clearly, this deterrence approach did not work, and each president since then has reckoned with issues of immigration, resulting in disjointed, easy-come-easy-go executive policy made up of executive orders and administrative measures under sitting presidents. Shortly after taking office, President Biden issued an executive order with the goal of starting the process to reorganize the U.S. refugee resettlement program to allow “climate refugees” by ordering an interagency report. This report highlighted the lack of climate change refugee resettlement channels, but offered the possibility of granting case-by-case parole for climate affected individuals as a short-term solution. Additionally, the report cited measures by other countries, such as humanitarian visas, labor mobility schemes, and education programs or sponsorships accessible to refugees and other forcibly displaced persons, which provide a path to permanent residency. None of these are long-term policy solutions, but rather seek to squeeze climate refugees into existing policy in any way they may fit. Even if the Biden administration does continue these efforts to protect climate refugees, these measures are easily undone by subsequent administrations.

Congress has not frequently passed dramatic changes to U.S. immigration law; arguably, the last major legislation was during the Reagan administration in 1986, when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act making it a criminal offense for employers to hire undocumented migrants, offering legal status to some undocumented migrants who had been in the U.S. before 1982, and increasing security-based deterrence measures at the southern border. Clearly, this deterrence approach did not work, and each president since then has reckoned with issues of immigration, resulting in disjointed, easy-come-easy-go executive policy made up of executive orders and administrative measures under sitting presidents. Shortly after taking office, President Biden issued an executive order with the goal of starting the process to reorganize the U.S. refugee resettlement program to allow “climate refugees” by ordering an interagency report. This report highlighted the lack of climate change refugee resettlement channels, but offered the possibility of granting case-by-case parole for climate affected individuals as a short-term solution. Additionally, the report cited measures by other countries, such as humanitarian visas, labor mobility schemes, and education programs or sponsorships accessible to refugees and other forcibly displaced persons, which provide a path to permanent residency. None of these are long-term policy solutions, but rather seek to squeeze climate refugees into existing policy in any way they may fit. Even if the Biden administration does continue these efforts to protect climate refugees, these measures are easily undone by subsequent administrations.

A number of policy options are available to the United States to rectify the absence of protections for climate refugees. In addition to parole or humanitarian visas, the U.S. could, as it has done before, instruct agencies to grant refugee status even when an individual does not strictly meet the definition of a “refugee.” The most common criteria disregarded under these conditions is the requirement that one be outside their country of origin. This adjustment could be very beneficial to climate refugees. Agencies could also stretch the meaning of existing “persecution” based definitions to somehow include climate change, though this may be limited to situations where drought, natural disaster, and other factors lead to actual conflict.

The most long-term solution would be the first sweeping immigration legislation to be passed since Reagan: a change to the legal definition of a “refugee” set out under the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act to one that includes climate change, or specifically sets out a definition of “climate refugee.” Such a piece of legislation goes beyond the UN Covenant, so the United States and other UN members currently lack incentives to initiate it, but sadly incentives may change globally as climate refugees grow in numbers due to worsening conditions.

Carly Gillingham anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Carly Gillingham anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

The Legality of Ranked Choice Voting

For a number of reasons, Jared Golden (D-ME) made national news when he was elected to represent Maine’s second congressional district (CD-2). First, CD-2 is roughly ten points more conservative than the nation as a whole and voted for former President Trump twice. Second, his victory meant the Democratic party would occupy all of New England’s House seats. Third, his election was the first time that CD-2 failed to elect an incumbent running for re-election in over 100 years. Finally, through the mechanics of Maine’s Rank-Choice Voting (RCV) system, Golden won despite initially having 2000 votes fewer than incumbent Bruce Poliquin. Poliquin filed a slew of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of RCV, but Golden was ultimately seated.

As more jurisdictions begin to consider implementing RCV, both state and federal courts will have to determine the legal contours of RCV. This blog post will briefly describe the history and mechanics of RCV before surveying the serious challenges RCV has faced and will continue to face at both the state and federal level.

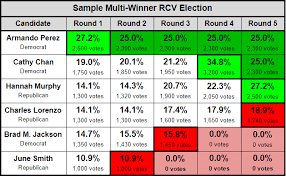

What is RCV and How Did it End Up in Maine?

RCV is a voting system that allows voters to pick a preferred order of candidates for any given position. If one candidate is the first choice of more than 50% of the voters, they are the winner of the election. However, if no candidate successfully secures 50% of first-choice ballots, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Officials then conduct a new round of counting, redistributing votes for the eliminated candidate(s) based on each effected ballot’s second choice. The process repeats itself until one candidate has at least 50% of the vote.

Proponents of RCV claim that it improves voter turnout, minimizes negative campaigning, and increases faith in elections. It also prevents candidates from winning elections who are actively disliked by the majority of voters. With states often being the laboratories for legislative policy, Maine was an obvious choice for targeting passage. Maine has a long history of electing independent politicians or voting heavily for third party candidates. Between Independent Jim Longley’s victory in 1974 with only 39.7% of the vote and the enactment of RCV in 2016, only two governors have been elected with a majority of the vote.

Although Maine’s affinity for independent-minded politicians often results in politically moderate governors, Paul Lepage, a Tea Party favorite and self-proclaimed “Trump before Donald Trump became popular,” was elected in 2012 with 37% of the vote. With shocking disapproval numbers for the new governor, advocates pitched RCV as a way to preserve Maine’s unique history of voting for third-party candidates while also preventing unpopular figures from claiming the governorship. In 2016, voters passed an initiative implementing RCV for all elections.

Source of Constitutionality Concerns

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

One Person One Vote and Burdens on the Right to Vote

Article 1 Section 4 of the Constitution grants states broad discretion to choose “[t]he Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for [federal] Senators and Representatives”. Having a novel method of electing officials is not per se unconstitutional, so Poliquin’s lawsuit claimed that RCV violates the federal right to vote. He argued that voters whose initial preferences are eliminated get to vote more than once – once in the initial round, and again in each subsequent round where their second, third, or even fourth preference is counted. In Baber v. Dunlap (D. Me. 2018), Judge Lance E. Walker was not sympathetic. Judge Walker found that those who voted for Poliquin as their first choice had their votes counted just as much as those who voted for disqualified candidates and whose votes were distributed to second choices. Ultimately, he found that the process did not dilute or make irrelevant the votes listing Poliquin or Golden as a first choice.

Poliquin also argued that the Constitution requires the winners of federal offices to be determined by the plurality of the votes. Walker, a Trump appointee, found that Article I of the Constitution does not require states to declare winners based on the winner of the plurality vote: “There is no textual support for this argument and a great deal of historical support to undermine it.” For example, Judge Walker noted that several states require majority votes for elections through the use of run offs, yet these schemes have never been closely scrutinized under Article I. With respect to the plain text, Walker was equally unequivocal in his conclusion: “The framers knew how to distinguish between plurality and majority voting, and did so in other contexts in the Constitution, which leads to the sensible conclusion that they purposefully did not do so in Article I, section 2.”

Other jurisdictions have agreed RCV does not violate the Constitution. The 9th Circuit, ruling on San Francisco’s RCV scheme, stated “the City’s restricted [RCV] system is not analogous to limitations on voting in successive elections, because in San Francisco’s system, no voter is denied an opportunity to cast a ballot at the same time and with the same degree of choice among candidates available to other voters.” Thus, the weight of legal authority indicates that the Constitution does not prohibit states from implementing RCV.

State Constitutionality

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Conclusion

Following the Maine Supreme Court’s advisory opinion, the Maine legislature has tried to amend the state constitution to allow for RCV for state general election. Even if such efforts are successful in Maine, RCV faces challenges elsewhere. The Supreme Court of Alaska, the only other state with RCV, is heard a case on RCV’s constitutionality in January 2022. Meanwhile, voters in Massachusetts turned down RCV at the ballot box. Thus, RCV faces seriously political and legal hurdles to gaining widespread implementation.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.