Disparate Impact in Machine Learning

Machine learning or “AI” is a novel approach to solving problems with software. Computer programs are designed to take large amounts of data as inputs, and recognize patterns that are difficult for humans to see. These patterns are so complex, it is sometimes unclear what parts of the data the machine is relying on to make a decision. This type of black box often produces useful predictions, but it is unclear whether the predictions are made based on forbidden inferences. It is possible that machine learning algorithms used in banking, real estate, and employment rely upon impermissible data related to protected classes, and therefore violate fair credit, housing, and labor laws.

Machine learning, like all programmed software, follows certain rules. The software generally compares images or numbers with

descriptions. For instance, facial recognition software may take as inputs pictures of faces, labeled with names, and then identify patterns in the face to associate with the name. Once the software is trained, it can be fed a picture of a face without a name, and the software will use the patterns it has developed to determine the name of the person that face belongs to. If the provided data is accurately prepared and labeled, the software usually works. If there are errors in the data, the software will learn the wrong things–and be unreliable. This principle is known as “garbage in, garbage out”–machine learning is only ever as reliable as the data it works with.

This causes problems when machine learning is applied to data that has racial bias baked-in to its core. Machine learning has been used in the criminal justice system to purportedly predict–based on a lengthy questionnaire–whether a perpetrator is likely to reoffend. The software was, after controlling for arrest type and history, 77% more likely to wrongfully predict that black defendants would re-offend than white defendants. Algorithms used by mortgage lenders charge higher interest rates to black and latino borrowers. A tenant screening company was found to rely partly on “arrest records, disability, race, and national origin” in its algorithms. When biases are already present in society, machine learning spots these patterns, uses them, and reinforces them.

There are two ways of interpreting the racial effect of machine learning under discrimination law: disparate treatment and disparate impact. Disparate treatment is fairly cut-and-dry, it prohibits treating members of a protected class differently from members of an unprotected class. For instance, giving a loan to a white person, but denying the same loan to a similarly situated black person, is disparate treatment. Disparate impact is using a neutral factor for making a decision that affects a protected class more than an unprotected class. Giving a loan to a person living in a majority-white zip code, while refusing the same loan to a similarly situated person living in a black-majority zip code, creates a disparate impact.

There are two ways of interpreting the racial effect of machine learning under discrimination law: disparate treatment and disparate impact. Disparate treatment is fairly cut-and-dry, it prohibits treating members of a protected class differently from members of an unprotected class. For instance, giving a loan to a white person, but denying the same loan to a similarly situated black person, is disparate treatment. Disparate impact is using a neutral factor for making a decision that affects a protected class more than an unprotected class. Giving a loan to a person living in a majority-white zip code, while refusing the same loan to a similarly situated person living in a black-majority zip code, creates a disparate impact.

Whether machine learning creates disparate treatment, disparate impact, or neither, depends on the lens the system is viewed through. If the software makes a decision based on a pattern that is the machine equivalent to protected class status, then it is committing disparate treatment discrimination. If a lender uses the software as its factor in deciding whether to grant a loan, and the software is more likely to approve loans to unprotected class members than it is to approve loans to similarly situated protected class members, then the lender is committing disparate impact discrimination. And if a lender uses software that relies on permitted factors, such as education level, yet nevertheless winds up approving more loans for unprotected class member than it does for protected class members, the process could be discriminatory but not actionable under either disparate treatment or disparate impact theory.

The problem thus depends in part on understanding how the machine interprets the data–the exact information we often lack when machine learning is particularly complex. Thus, instead of relying on either disparate impact or disparate treatment theory, perhaps legal analysis of discrimination in machine learning should be entirely outcomes-driven. If, in fact, an algorithm wrongly predicts the likelihood of an event occurring, and that algorithm is less accurate for protected class members than unprotected class members, the algorithm should be considered prima facie discriminatory. Such a solution is viable for examining recidivism, interest rates and loan repayment, but it may be insufficient to cover problems like housing denials or employment. If an algorithm denies protected class members access to housing in the first place, it is difficult to falsify the algorithm’s decision, as nonpayment or other issues necessarily do not arise.

Machine learning offers great promise to escape the racial biases of our past if it is programmed to only rely on neutral factors. Unfortunately, it is currently impossible to determine which factors used by machines are truly neutral. Improperly configured machine learning has led to higher incarceration rates for black inmates and higher loan interest rates for black and latino homeowners. Such abuses of machine learning technology must be rejected by the law.

Schecharya Flatté anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Schecharya Flatté anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Telehealth in the Era of COVID-19 and Beyond

Governor Charlie Baker of Massachusetts has recently issued an Order Expanding Access to Telehealth Services and to Protect Health Care Providers. The order, issued in March, is a public health response to the state’s state of emergency due to the Coronavirus or COVID-19 outbreak. Under the order, the Group Insurance Commission, all Commercial Health Insurers, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Inc. and health maintenance organizations regulated by the Division of Insurance are required to let all in-network providers deliver clinically appropriate, medically necessary covered services to their members via telehealth, and to mandate reimbursement for these services. The purpose behind the Order is to encourage the use of telehealth in the mainstream of health care provision, as a “legitimate way for clinicians to support and provide services to their patients.”

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts has recorded over half a million patient telehealth visits over a six-week span and that number is only increasing with time. In comparison, the average number of telehealth visits before the COVID-19 pandemic was 5,000. The demand for health care and medical advice without the requirement of an in-person appointment has soared in light of the outbreak that prevents or prohibits people from attending one due to social distancing guidelines. Prior to the crisis posed by the pandemic and before Governor Baker’s order, hospitals and doctors were disincentivized from offering telehealth visits because health insurers did not cover them or would offer a smaller pay as compared to in-person visits. By introducing payment parity between in-person visits and virtual ones, the order expands access to care as current Massachusetts law allows insurers to limit coverage of telehealth services to insurer-approved health care providers in a telemedicine network.

The arrival of the pandemic and state of emergency has pushed for a rapid expansion of the use of technology in the practice of health care. Many of the barriers to access of health care via telemedicine have shifted in a relatively short period of time. In addition to Governor Baker’s order for payment parity, for example, the Governor allowed health care providers outside Massachusetts to obtain emergency licenses to practice within the Commonwealth. Before this and other similar licensure waivers, licensure requirements usually demand that providers be licensed within the state that their patients reside. By waiving this requirement, providers can expand the network of care they are able to provide, and telehealth serves to eliminate the only other barrier--distance.

An additional movement towards lifting barriers to the implementation of telehealth services is the relaxation of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) noncompliance enforcements by Health and Human Services, with the caveat that providers engage in good faith provision of telehealth during the national health emergency posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. HIPAA rules require the protection of privacy and security of health information. The discretionary enforcement order allows health care providers to use any non-public facing audio or video communication products during the COVID-19 public health emergency. This movement attempts to strike a balance between providing access to care during a national health emergency and the privacy protections against the risk of information exposure that are expected by patients in their interactions with their health care providers.

An additional movement towards lifting barriers to the implementation of telehealth services is the relaxation of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) noncompliance enforcements by Health and Human Services, with the caveat that providers engage in good faith provision of telehealth during the national health emergency posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. HIPAA rules require the protection of privacy and security of health information. The discretionary enforcement order allows health care providers to use any non-public facing audio or video communication products during the COVID-19 public health emergency. This movement attempts to strike a balance between providing access to care during a national health emergency and the privacy protections against the risk of information exposure that are expected by patients in their interactions with their health care providers.

Another response to the public health crisis has been issued by the United States Drug Enforcement Agency, notifying that practitioners can, in light of the state of emergency, prescribe controlled substances in the absence of an in-person patient encounter. Prior, the prescription of controlled substances via telehealth evaluation was prohibited entirely. Now, prescribers are allowed to write prescriptions so long as: (1) the prescription is issued for a legitimate medical purpose in the course of the practitioner’s usual professional practice; (2) the telemedicine communication is conducted in a real-time, two-way, audio-visual communication system; and (3) the practitioner is acting in accordance to state and federal law.

As of May 2020, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has initiated a four-phase reopening plan, beginning with hospitals and community health centers. The East Boston Neighborhood Health Center, for example, has indicated that they have an extensive screening process for patients who head over for in-person appointments, including the use of phone-tracking technology to notify staff when the patient has entered the building in an attempt to streamline entrance to examination rooms. The continued need to introduce methods of facilitating social distancing within the hospitals and community health centers indicates that there will be a continued incentive for the provision of telehealth services. The East Boston Neighborhood Health Center reports that, in the first phase of reopening, they expect 25% of visits to be in-person, with 75% of visits to continue to be via telehealth services such as video chat or over the phone.

While some find telehealth services to be inconvenient, due to technological challenges and care that requires more physical examination than can be completed over the phone or by video calling, it seems likely that we will see a blended version of care into the future. Health care practitioners have indicated that, while telemedicine is not a complete substitution of physically seeing and examining patients, being able to speak with a patient in combination with access to the patient’s medical history goes a long way in being able to diagnose and treat health problems. There is a growing sense of certainty that the use of a technology-based health care experience will “become the new normal.”

The natural question is how the legal landscape will have to adjust in response to the shift as society reopens and the balance of the role of technology in a “new normal” becomes more urgent to strike. Many of the barriers to the expansion of telehealth have been rapidly eliminated as a temporary alleviation in direct response to the public health crisis posed by COVID-19. This indicates that the changes are ephemeral; however, with the uncertainty posed by the length of the pandemic and the resulting impact this will have on the use of technology in health care, it seems likely that some of these legal shifts will need to be modified, rather than entirely eliminated, moving forward.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

United States v. Safehouse: Could Philadelphia be the First State in the Nation to Implement a Supervised Drug Injection Site?

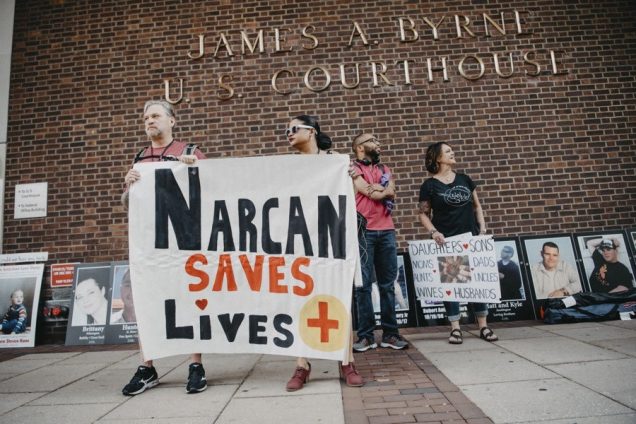

The opioid epidemic is one of the worst public health crises affecting the United States, and the rate of deaths resulting from opioid overdose has steadily increased. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a record high of more than 70,000 people died of a drug overdose in the United States in 2017, and over 47,000 of those deaths were from opioid overdoses. As lawmakers attempt to address this epidemic through public health initiatives , health advocates increasingly recommend using supervised injection sites to curb overdose deaths. Though legal barriers to this in the US exist, a recent District Court ruling in United States v. Safehouse may have paved the way for implementation of the first site of this kind in the US.

Injection sites provide a space where those using intravenous drugs can inject under the supervision of a medical professional ready to intervene in the event of an overdose, instead of unsupervised use where an overdose is more likely to be deadly. Supervised injection sites, also called safe injection facilities or safe consumption spaces, are a tertiary preventative public health measure aimed at combating overdose deaths and decreasing public use. In these spaces, injection drug users can self-administer drugs they bring to the facility in a controlled, sanitary environment under medical supervision. The medical personnel on staff at the sites do not directly handle the drugs and are there purely to administer Naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, in case of an overdose.

Despite the growing global presence in Europe, Australia, and Canada, scientific support for safe injection sites, and the interest of several cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Seattle, and San Francisco it is not entirely certain they can be operated in the United States. The Controlled Substances Act § 856, which regulates the production, possession, and distribution of controlled substances, makes it a criminal offense to maintain a drug-involved premises. Most academics agree that this “Crack House” Statute forbids safe injection sites and the courts can not definitively decide if safe injection site violate federal law until one is operational.

However, recently these assumptions have been called into question. Safe injection site proponents in many states have been appealing to legislatures and public health officials for funding. This effort has been largely unsuccessful due to political opposition and the looming threat of a federal lawsuit. In Philadelphia, which has the highest overdose rate of any major US city, a poll found roughly half of Philadelphians support a proposed safe injection site. Safehouse is a Philadelphia nonprofit that seeks to build the first safe injection site in the nation. In January 2018, Philadelphia health officials gave Safehouse permission to move forward with only private funds—preventing the need for legislative backing and appropriations.

In February 2019, federal prosecutors launched a civil lawsuit asking the U.S. District Court to rule on the legality of the Safehouse supervised consumption site plan, rather than waiting for the site to be built and then bringing federal criminal charges. U.S. Attorney William McSwain, working with Pennsylvania-based prosecutors, is seeking a declaratory judgment that medically supervised consumption sites per se violate 21 U.S.C § 856(a)(2)— the federal “Crack House” statute.

In February 2020, the court issued United States v. Safehouse, ruling that Safehouse’s plan to build a site where people could bring previously obtained drugs and use them under medical supervision for the purpose of combating fatal overdoses does not violate the Controlled Substances Act. Judge McHugh, looking at Congressional intent, ruled that §856 “does not prohibit Safehouse’s proposed medically supervised consumption rooms because Safehouse does not plan to operate them 'for the purpose of’ unlawful drug use within the meaning of the statute.” McHugh determines that at the time of enacting §856(a), Congress was focused on crack houses, not supervised drug injection sites. Even when amended in 2003, the focus was on “drug-fueled raves.” McHugh found that Congress neither expressly prohibited or authorized injection sites, so if §856(a) did not implicitly prohibit a consumption site, then implicit authorization naturally followed.

The question that the court addresses is whether the statute requires the defendant to know that third parties would enter their premises to consume illicit drugs, or rather that the defendant knowingly held their premises open for the purpose of facilitating illicit drug consumption. Judge McHugh concludes that the actor must “have acted for the proscribed purpose” to violate the statute. Therefore, the accused under a §856(a)(2) violation must have the purpose of facilitating illegal controlled substance use in the maintenance of a property.

Safehouse is planning “to make a place available for the purposes of reducing the harm of drug use, administering medical care, encouraging drug treatment, and connecting participants with social services.” The district court reasons that because of this, it could not conclude that Safehouse has, as a significant purpose, “the objective of facilitating drug use.”

In the wake of the ruling, U.S. Attorney McSwain announced that “this case is obviously far from over” and it is likely that the federal government will continue to litigate it. It is not unlikely that the Court that may hear this case on appeal disagrees with the District Court’s construction and strikes the legality of a supervised injection site based not on the intent of the person who controls the space, but the intent of the attendee of the site to use illicit drugs at that site, which has been the prevailing opinion up until the point of this ruling.

While the Safehouse case stands for an unexpected legal victory by way of the possibility of a supervised injection site to be opened in the United States, Philadelphia itself may not be the first state in the nation to implement one. The public sentiment in the wake of the decision was largely negative, with the local community being virulently opposed to the idea of a site being opened in the neighborhood from fear of what dangerous circumstances a site might attract. Plans to open the Safehouse site were put on indefinite hold. While proponents of Safehouse won the legal battle, winning over the community seems to be more of uphill battle than anticipated.

At this point in time, the legal position of supervised injection sites in the United States is tentatively positive. States who are looking to introduce this harm reduction initiative, and to be the first in the nation to do so, should take the opportunity to garner support from legislatures and local health care communities. While Philadelphia’s progression seems to be stymied, the District Court’s ruling provides significant legal precedent to ground encouragement for sites to be lobbied for in other states or cities that might not face the same type of community rejection that has prevented the opening of Safehouse.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Waiting Game: Supreme Court’s Decision on the Lawfulness of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program

As May 2020 comes to an end, many eagerly await a Supreme Court decision that could affect the futures of thousands of DACA recipients and shape immigration policy as we know it. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is the program that is currently under scrutiny; in particular the Supreme Court will be deciding on the following two issues: (1) “Whether or not the Trump administration’s decision to end DACA can be reviewed by the courts at all?” and (2) “Whether or not the Trump administration’s termination of DACA was lawful?” This program was first instituted under the Obama Administration as an executive action to do the following for qualified Dreamers who completed the process of a first-time or renewal application: (1) protection from deportation for a time period, and (2) work authorization for a set period of time.

During the Obama Administration, the DREAM Act of 2010 (H.R. 6497) was proposed and passed in the House but did not pass the Senate. The purpose, like its other variations, was intended to aid undocumented individuals by providing them a way to eventually reach legal status, because they were brought to the United States when they were children and have to live with a continued sense of uncertainty that attaches to being undocumented. In its stead, the Obama Administration designed a temporary solution, which came to be known as DACA, in which an individual could qualify by meeting a series of requirements (i.e. arriving in the United States before they turned sixteen years old).

This policy gave a lot of individuals hope, but everything changed with the arrival of the Trump Administration. The Trump Administration’s policies quickly took on an anti-immigration rhetoric, and his Administration rescinded the policy on the basis that it was illegal. Thereafter, lawsuits followed with Department of Homeland Security, et al., v. Regents of the University of California, et al. reaching the Supreme Court level.

Regarding the two issues laid out above, there are many ways the decision could go, but the one that would have the worst effect on DACA recipients would be the court siding on the Trump Administration’s side in saying that “DACA was an unconstitutional use of presidential power to begin with.” This could have a devastating impact on DACA recipients especially at a time when they find themselves in the midst of the COVID-19 global pandemic alongside the rest of the world.

For example, ABC News quotes a college student saying “As a DACA recipient, and everything going on with COVID-19 and as well with the Supreme Court ruling coming at any time -- It's been very stressful.” On top of college, she works with authorization under DACA, but COVID-19 has added other stressors as she finds herself as the only provider at home. Ending DACA at a time like this would end up being very challenging and harmful for individuals like these who are trying to stay afloat during this pandemic.

Nevertheless, as this country struggles to recover from this pandemic, the most interesting development has happened to this Supreme Court case showing how vital Dreamers and immigrants have been to making this country function smoothly despite the havoc wreaked by the virus. A CNN report discusses how: “A letter sent to the Supreme Court states approximately 27,000 Dreamers are health care workers -- including 200 medical students, physician assistants, and doctors -- some of whom are now on the front lines in hospitals across the country.” The Supreme Court agreed to take this brief into consideration, and it makes one wonder whether the timing of the decision during a pandemic and the supplemental brief will have any impact at all?

Nevertheless, as this country struggles to recover from this pandemic, the most interesting development has happened to this Supreme Court case showing how vital Dreamers and immigrants have been to making this country function smoothly despite the havoc wreaked by the virus. A CNN report discusses how: “A letter sent to the Supreme Court states approximately 27,000 Dreamers are health care workers -- including 200 medical students, physician assistants, and doctors -- some of whom are now on the front lines in hospitals across the country.” The Supreme Court agreed to take this brief into consideration, and it makes one wonder whether the timing of the decision during a pandemic and the supplemental brief will have any impact at all?

Despite the positive contributions of these and other essential individuals, there have been a lot of issues that have also surfaced reflecting further difficulties that Dreamers are enduring. An example of this is federal funding under CARES Act. The pandemic has had even more disastrous effects on particular communities, and though the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 was passed with a part of it designed to provide aid and federal dollars to help students, and yet the benefits are not available to everyone. DACA students could not qualify to receive money under this Act, and it was one of the reasons the Democrats reached out to Secretary DeVos to change the language but to no avail. The House has brought another bill to the forefront, the Heroes Act, which proposes many changes; one aspect of which directly seeks to overturn “Secretary DeVos’s decision to exclude DACA students from the emergency aid.”

This is a hopeful change, but the culmination of issues including the Supreme Court decision yet to be released, the uncertainty of COVID-19 on employment, health, and education, and a delay in passing the House bill paints a bleak picture.

Yet, at the end of the day, it is as Antonio Alarcon described it on CNN: “We’re hopeful that the Supreme Court will see the humanity of our stories and see the humanity of our families, because at the end of the day, this is a nation of immigrants.”

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Fear of Forcible Eviction: Deficiencies in India’s Forest Rights Act’s Recognition of Indigenous Land Rights

Land rights has been an ongoing issue in India for many years now, but there are some communities that end up being more vulnerable than others. This was made clear on February 13th, 2019, when the Supreme Court of India released an order for mass evictions of indigenous forest dwellers from forest areas for the goal of conserving these lands. Here, the conflict itself is not surprising because evictions has been a persistent issue throughout Indian history, but it is the degree of how many individuals would be impacted that made this news so surprising.

This order was later stayed for the purpose of asking states to provide more details on the steps of eviction due to the nearly one  to two million indigenous people who would be affected by the declaration. This order is significant for illustrating the deficiency in current legislation and also for shedding light on the consequences faced by vulnerable communities who live in fear of being forcibly evicted from lands that they live on, depend on, and survive on. This article will lay out the process and current critiques of the FRA, and further discuss the ongoing arguments for and against the mass eviction ordered in the February 13th decision.

to two million indigenous people who would be affected by the declaration. This order is significant for illustrating the deficiency in current legislation and also for shedding light on the consequences faced by vulnerable communities who live in fear of being forcibly evicted from lands that they live on, depend on, and survive on. This article will lay out the process and current critiques of the FRA, and further discuss the ongoing arguments for and against the mass eviction ordered in the February 13th decision.

Forest Rights Act of 2006

Enacted in 2006, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act (commonly referred to as the Forest Rights Act (FRA)) was intended to protect indigenous populations. The FRA sought to substantiate and recognize land claims of forest dwellers. The FRA brings two groupings of individuals within its purview:

- Forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes, which includes members of Scheduled Tribes who primarily reside and live off the land, and

- Other traditional forest dwellers, which includes anyone who can prove that they have resided on and lived off the land for “at least three generations.”

To obtain legal recognition of their land rights individuals must file a three stage claim.

- Stage 1: The first stage begins at the level of the Gram Sabha, which is generally a village assembly at which a person presents their claim to the land. At this assembly people are elected to the Forest Rights Committee, which investigates the claim and presents its findings to the village assembly. Acceptable forms of proof to support a land claim are governed by Rule 13 of the Comprehensive Tribal Rules.

- Stage 2: After the Forest Rights Committee presents findings to the village assembly, the second stage begins with the review of the claim by the Sub-Divisional Level Committee.

- Stage 3: Thereafter, the third stage is set at the District-Level Committee which determines the fate of the claim; either a claim will be accepted or rejected. If rejected, an appeals process is available to the claimant, but it is uncommon.

Despite being considered a step forward, the FRA’s deficiencies serve to negatively impact indigenous forest dwellers.

- Inexperience: First, there is the issue of inexperience with the legal system as this Act imposes a legal process that these groups may be unfamiliar with and therefore will find it more difficult to complete fully and accurately.

- Inaccessibility: Second, there is the issue of inaccessibility, because the Act imposes a standard form, but does not consider diversity (i.e. approximately 705 diverse ethnic groups that are legally recognized) and how such a form could be inaccessible to individuals not speaking the same language or who have different customs on resolving disputes.

- Impractical: Third, there is the issue of impractical standards. As the definition of the other traditional forest dwellers mentioned above indicates, part of the process of getting the land right recognition requires a claimant to present proof of residence in the forest area for at least three generations. The following two factors show how this is not a practical standard:

- First, having difficulty preserving documentation that dates so far back when living a nomadic way of life,

- Second, it be unlikely to have had an opportunity or need to compile such documentation beforehand.

- Inadequacy: Lastly, there is the issue of inadequacy, as this procedure is set up in a way that can be influenced by adverse interest groups who may have alternate plans for the forest areas that indigenous groups call home.

These deficiencies illustrate how complex the issue is, and how there are a number of structural issues that need to be resolved in order to provide the protection that these groups need.

Arguments For And Against Forced Evictions

The February 13th order is unclear on the forced eviction of indigenous groups. Those opposed to indigenous groups residing in forest lands claim that the current destruction of forest areas is attributable to indigenous dwellers whose practices and way of life prove to be harmful to these areas. Furthermore, opponents such as the conservationists are not entirely sold on the purpose the FRA serves in recognition of land rights.

Supporters of indigenous forest dwellers, however, characterize these dwellers as the forest’s guardians because their practices prove to be less harmful to the land. Having resided on the land for many generations, their history, culture, and practices are tied with the land in an inexplicable way, and so evictions can prove to be disastrous to these communities especially when they are executed through force.

There have been many incidents when forced evictions have been executed through use of force (i.e. threatening behavior, destruction of home, etc.). Such evictions are expected to have dire consequences for evicted individuals, but with communities as cohesive as indigenous groups the consequences are even more far reaching. Not only are they at risk of induced poverty and danger, but community and social life are broken down forever.

These consequences indicate a systemic and pervasive issue that requires resolution. The starting point for this is amending the FRA by making it simpler and stronger by addressing the deficiencies listed above. Only through amending this Act can real change begin to happen.

Note: This article is based on a paper originally submitted in the Environmental Justice class at BU Law.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.