The Push and Pull of Municipal Fossil Fuel Bans in Massachusetts

In 2019, Brookline, Massachusetts became the first municipality outside of California to ban fossil fuels in new construction. The move was part of a growing movement among cities and towns to ban fossil fuel infrastructure, such as hookups for oil or natural gas use, in newly constructed buildings. Fossil fuel bans of this nature typically aim to curb emissions from energy use in buildings, which in many municipalities is the leading source of emissions, through electrification. Electricity use in buildings produces less carbon emissions than burning oil and gas directly and those emissions will continue to decrease as more renewable resources are added to the electricity grid.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Unfortunately for Brookline, the Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit disapproved of Brookline’s fossil fuel ban in 2020, finding that the ban was preempted by state law. Not easily deterred, Brookline passed a new set of by-laws in 2021. These by-laws were worded differently than the first attempt, framed as requirements for building permits rather than an outright ban. However, these by-laws fared no better than the first ban, and the Attorney General issued a decision in 2022 once again disapproving of the by-law amendments because they were preempted by Chapter 40A (regulating municipal zoning), Chapter 164 (regulating natural gas), and the State Building Code.

Meanwhile, in the time between when Brookline passed its first fossil fuel ban and when the Attorney General issued its decision about the legality of the second ban, dozens of other Massachusetts municipalities became interested in enacting fossil fuel bans of their own. Some of these municipalities submitted home rule petitions to the Massachusetts legislature, asking the legislature to grant their individual municipalities the authority to ban fossil fuel infrastructure on a case-by-case basis. State Representative Tami Gouveia and State Senator Jamie Eldridge of Acton also introduced a bill during the 2021–2022 session that would have granted every municipality in the commonwealth the power to adopt a requirement for all-electric construction without passing and submitting a home rule petition.

The result was a compromise: The legislature passed An Act Driving Clean Energy and Offshore Wind in August of 2022. The law, among other things, authorized a pilot program enabling up to ten cities and towns to adopt and amend ordinances or by-laws to require new building construction or major renovation projects to be fossil fuel-free. The Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER) was tasked with developing the pilot program and deciding which municipalities would participate. Among requirements for cities and towns seeking to join the pilot program for fossil fuel bans is having a minimum of ten percent affordable housing.

DOER has already received more than ten applications from Massachusetts cities and towns wishing to join the pilot program, but under the draft regulations DOER published in February of this year, municipalities would have to wait until early 2024 at the earliest to implement their bans. This long period for implementation has disturbed members of the legislature who championed and passed the pilot program into law. Senator Michael Barrett, the Senate Chair of the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy recently told GBH News that the proposal would “delay the entire process much longer than the Legislature ever imagined.” Pressure from both the legislature and the municipalities seeking to join the pilot program will likely continue to mount as the group of cities and towns now includes the City of Boston, the largest city in the commonwealth. With advocacy groups concerned that the delay combined with limiting the pilot program to ten municipalities will hold the commonwealth back from meeting its goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050, legislators may be reconsidering the more conservative approach they took by passing the pilot program rather than blanket approval for cities and towns to enact fossil fuel bans.

Opponents and those concerned about the impacts of fossil fuel bans, however, may be heartened by the delay. Governor Charlie Baker considered vetoing the energy bill because of the fossil fuel ban pilot program because of the possibility that banning fossil fuels in new construction might make it more difficult to build affordable housing. In a state experiencing what many characterize as an affordable housing crisis, this concern is not uncommon, the thought process being that if there is inconsistency in requirements for developers between municipalities, developers, especially developers of affordable housing, will prioritize projects in communities with fewer or less expensive requirements. Many of the cities and towns that have already stepped forward to join the pilot program are fairly wealthy and may not be as concerned with the affect of a fossil fuel ban on the costs of housing development.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

Yet, there may still be reason for optimism. As an example of what may be possible in a future that includes municipal fossil fuel bans, the Town of Brookline recently approved an affordable housing project that will be powered exclusively by electricity. In addition, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently signed an executive order that bans fossil fuel use in new city-owned buildings and in major renovations of municipal buildings. Even without municipal fossil fuel bans in place, some developers, including affordable housing developers, in Massachusetts communities are choosing to build fossil fuel-free.

The future of fossil fuel-free building in Massachusetts is uncertain. The legislature may choose to take a more aggressive approach than it did during the last session, or it may wait to see how DOER’s implementation of the pilot program goes, leaving Massachusetts cities and towns and developers to continue to innovate on their own. States are often called “laboratories of democracy,” but when it comes to issues like climate change, where municipalities acting individually may be able to make a large impact, that label may better suit cities and towns as they try again and again to form creative solutions where their state legislatures fall short.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Hayley Kallfelz graduated with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

End the Request: It’s Time for Boston’s Biggest Landowners to Pay Their Fair Share

For the second time, Massachusetts State Representative Erika Uyterhoeven (D-Somerville) filed a bill concerning payments in lieu of taxes to cities and towns. This bill would strengthen and codify a Boston program, which requests payment from certain institutions that do not pay property taxes. It is important that this bill passes during the 2023-24 session because, without it, Boston (and other municipalities) will continue to subsidize large, private organizations at the expense of its own residents.

The City of Boston’s budget

The City of Boston’s operating budget consists of revenue from property taxes, state aid, local revenue, and, to a small extent, non-recurring revenue (e.g., funds from the American Rescue Plan Act). This revenue is used to fund programs and services, including public education, public safety, city departments, and transportation. Property taxes are consistently the City’s largest source of revenue, and its share size continues to increase as state aid decreases. For example, 74% of the City’s revenue is derived from property taxes this year compared to 52% in 2002.

Boston residential taxpayers currently pay $10.74 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge taxpayers spend $5.86; Somerville taxpayers spend $10.34 and Medford taxpayers spend $8.65. Boston commercial taxpayers, including small businesses pay $24.68 per $1,000 value in property taxes. This number is also higher than its surrounding municipalities: Cambridge commercial tax payers spend $11.23, Somerville commercial taxpayers spend $17.35, and Medford commercial taxpayers spend $16.56.

Part of the reason why Boston’s property taxes are so high is that Boston’s tax base is constrained. Boston’s geographic region is relatively small and is home to many tax-exempt institutions.

52% of Boston’s area is tax exempt.

Tax-exempt areas include public land owned by the city, state, and federal government along with private land owned by universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions. These institutions are not required to pay property taxes as nonprofit charitable organizations under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. In Boston, this includes large, private institutions––like Mass General Brigham, Harvard, Boston University, and Northeastern––that together own over $14 billion of Boston’s real estate.

These large institutions do make some financial contributions to the city of Boston via the Payment in Lieu of Tax (“PILOT”) program. The PILOT program asks educational, medical, and cultural institutions with more than $15 million worth of tax-exempt property to make voluntary payments to the City of Boston. These contributions are supposed to be 25% of the would-be property taxes, and up to 50% of this payment can be in the form of “community benefits.” The 25% represents a “fair share” because large institutions’ use of essential services, such as fire safety, roads, public transportation, and sewage disposal generally make up 25% of a municipality’s budget.

The PILOT task force defines Community benefits “as services that directly benefit City of Boston residents; support the City’s mission and priorities with the idea in mind that the City would support such an initiative in its budget if the institution did not provide it; emphasize ways in which the City and the institution can collaborate to address shared goals; and, are quantifiable.” For example, these services can take the form of individual scholarships and job training initiatives. Other examples include summer camp and after school activities, preventative medical care, and maintenance of public spaces.

PILOT does not go far enough

Institutions often do not fulfill their PILOT requests from the City of Boston. During the 2022 fiscal year, Northeastern met 67% of its PILOT request. Boston University and Harvard did better, meeting 80% and 79% of their PILOT requests, respectively. However, these institutions tend to max out their community benefits. For example, during the 2022 fiscal year, the City of Boston requested $66,709,087 from educational institutions and received $30,793,921 in community benefits and only $14,788,450 in cash contributions. Here, it is worth emphasizing that $66,709,087 is only one quarter of what these institutions would pay if their properties were not tax-exempt.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Ever more, these private institutions look increasingly less like tax-exempt charitable organizations. Many of the institutions have large budgets. For example, Harvard has its own Management Company overseeing the investing of its $53 billion endowment. Harvard Management Company is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit and does not pay property taxes in Boston.

Boston should be able to increase the amount of money generated from the city’s PILOT program to alleviate the pressure on its residents and small business owners and to ensure that large institutions pay their fair share for essential services. Changing these institutions from 501(c)(3) status to require payment of property taxes is likely a political and bureaucratic nightmare, especially given these institutions’ reliance on the nonprofit status. That said, some Massachusetts legislators are taking steps to ensure that universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions start to pay their fair share.

Bill H.2963

Representative Erika Uyterhoeven refiled Bill H.2963, An Act Relative to Payments In Lieu of Taxation by Organizations Exempt from the Property Tax on January 19 this year. The proposed bill:

- allows cities or towns to charge 501(c)(3) organizations 25% of their would-be property taxes, so long as the exempt organization owns at least $15 million worth of property;

- requires these cities or towns to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to describing the agreement between the municipality and the tax-exempt organizations; and

- allows these local ordinances and bylaws to have exemptions from payment and considerations of community benefits in lieu of cash contributions.

Importantly, this is a local option bill, which means that municipalities are allowed to require large, non-profit institutions to pay 25% of their would-be property taxes but do not have to. The language of this bill largely tracks Boston’s PILOT program but mandates (rather than requests) the payment of 25% of a large institution’s would-be taxes. It is not clear whether this mandate runs afoul of the Massachusetts Constitution, which requires properties in the same property class (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) to be taxed at the same rate. It is possible that the bill is meant to be a “fee” rather than a tax, in which case the funds should only be used for essential services.

During the 2021-22 session, Representative Uyterhoeven testified at the previous bill’s public hearing. She emphasized that the bill is for very large institutions and “not for churches, not for small kitchens, or anything like that, it’s really just for the large nonprofits, the health care facilities, universities. This comes from an equity issue around large nonprofits needing to pay their faire share to all of the things that municipal budgets serve them.” That said, the bill does not contemplate an exemption for churches, and it is possible that at least some churches have $15 worth of land and cannot afford the 25% of their would-be property taxes. It would be up to municipalities to include exemptions for specific organizations within their bylaws and ordinances, which may be politically difficult.

The City of Boston should opt-in

Bill H.2963 is currently with the Committee on Revenue. It is not clear that this bill has traction or will pass into law––the legislature has considered similar bills as early as 2013 and the bill was sent for study last session, often a quiet way to kill a bill.

However, if the bill does pass, Mayor Wu and her team should push to adopt an ordinance or bylaw given the City of Boston’s reliance on property taxes. Boston lawmakers should be conscious of their exemptions. One worry is that residents may make value judgments and target organizations that they do not like through a mandated fee.

Boston lawmakers should consider lowering the percentage of community benefits the City of Boston will accept. Although there is great value in community benefits, in practice they benefit individual residents rather than fund the City’s operating budget.

The Massachusetts legislature has an opportunity to fix a loophole in property taxes that allows large, private institutions to take advantage of their 501(c)(3) status to avoid paying property taxes. Bill H.2963 is a step in ensuring that these institutions start to pay their fair share and is a model for other states and municipalities dealing with similar challenges. If the bill becomes law, the City of Boston urgently needs to adopt an ordinance or bylaw to relieve economic pressure on residents and businesses, who currently fund the majority of the City’s operating budget.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Alison Kimball anticipates graduating with a juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Congestion Pricing: Addressing The True Cost of Cars

One of the most heartening social trends of the last couple of years has been a recognition of the true costs of car use in cities. Whether approaching it from the stance of climate change, health effects from air quality, physical safety on the roads, or social fragmentation from structures that isolate and alienate people, it has become increasingly clear that we do not properly value our roads. One policy with great potential to address all these concerns, while generating considerable revenue that could support mass transit in cities, is congestion pricing of key roads in urban centers.

The idea behind congestion pricing is that roadways are incredibly valuable real estate, which people do not pay to use (outside of some tolling on bridges and specific toll roads). The free use of the roads imposes significant social costs on the city's inhabitants through bumper-to-bumper traffic, costing people time, and polluting the air. A congestion pricing system would impose a toll on entrants to designated zones. This would reduce traffic by imposing the true costs of using the road, and hopefully, diverting people to use mass transit or other forms of transportation. The beneficial effects would range from clearing congestion, to reducing air pollution, to generating significant revenue for the city.

The idea behind congestion pricing is that roadways are incredibly valuable real estate, which people do not pay to use (outside of some tolling on bridges and specific toll roads). The free use of the roads imposes significant social costs on the city's inhabitants through bumper-to-bumper traffic, costing people time, and polluting the air. A congestion pricing system would impose a toll on entrants to designated zones. This would reduce traffic by imposing the true costs of using the road, and hopefully, diverting people to use mass transit or other forms of transportation. The beneficial effects would range from clearing congestion, to reducing air pollution, to generating significant revenue for the city.

This is no longer merely a thought experiment either. Notably, cities including London, Stockholm, and Singapore, have all implemented congestion pricing in their city centers to great positive effect. They generally see reduced car congestion, but also interestingly, greater total numbers of people accessing the city, as they come in via alternate methods. This increases economic value to the city without imposing any of the normal car related costs.

No American city has successfully implemented this policy yet, but New York is currently in the middle of a now 5 year long battle to try. In 2019, the New York State legislature passed, in the state budget, a law permitting the city of New York to implement a congestion pricing plan. Curiously, New York City does not control its own road system, and is therefore dependent on the state to give permission to implement such a project. This is relatively common in the U.S. and is in tension with the age-old principle of local control. It also raises a potential problem where a star city in a state drives a significant portion of that state’s revenue, but has strong political disagreements with the state government. In New York the success of the plan at the state level was over 50 years in the making. New York State had frequently prevented the city from implementing similar congestion pricing programs in the past, when the city had tried to reduce traffic.

Despite state approval, congestion pricing in New York has been stuck in limbo, in part due to federal law. Title 23 of the Federal Code prohibits municipalities from imposing tolls on roads constructed or maintained with federal funding, which include several New York City roads. To impose tolls, New York had to enlist in the Federal Highway Administration's Value Pricing Pilot Program (VPPP), which gives up to 15 cities or states special permission to experiment with toll related projects on federally funded roads. Congestion pricing plan falls under the purview of the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) because it is enrolled in the VPPP.

Passed in 1970, NEPA mandates environmental review of federal projects. While proponents argue that NEPA is an essential defense for the environment from human exploitation (both for its own sake and also to protect our habitat), critics traditionally argue it prevents profitable projects. Now environmentally minded advocates are increasingly frustrated with NEPA’s requirements. They argue NEPA’s onerous procedural requirements, which often require millions of dollars and years of effort, are inhibiting projects that would benefit the environment, violating its fundamental purpose.

It is clearly the case in New York right now that the city is suffering from these unnecessary delays. It took 2 full years just for the federal government to determine whether the appropriate environmental review was a relatively basic Environmental Assessment, or a complete Environmental Impact Assessment for the project and another 2 years to issue the determination report. Now, going on 5 years from initial passage, the city is still waiting for a final determination if the project is viable. All of this for a project that requires the city to build almost no physical infrastructure, and would dramatically reduce emissions and air pollution by reducing the number of cars driving in New York.

It is clearly the case in New York right now that the city is suffering from these unnecessary delays. It took 2 full years just for the federal government to determine whether the appropriate environmental review was a relatively basic Environmental Assessment, or a complete Environmental Impact Assessment for the project and another 2 years to issue the determination report. Now, going on 5 years from initial passage, the city is still waiting for a final determination if the project is viable. All of this for a project that requires the city to build almost no physical infrastructure, and would dramatically reduce emissions and air pollution by reducing the number of cars driving in New York.

The FHWA can remedy this issue by assigning congestion pricing projects a Categorical Exclusion (CE). A CE is used for projects that are known not to have negative environmental impacts. It exempts them from the entire Environmental Impact Statement and Environmental Assessment process. It is commonly used in projects where there will not be significant physical infrastructure created, much like the congest program. The programs would still have to present reasons why they should be granted the exclusion, so this will not totally eliminate any environmental review, but it will bring the level of review in line with the risks that the project actually presents.

New York’s experience shows the complex thicket of legislation and regulation that creative environmentalists must navigate in order to successfully pursue valuable projects. Congestion pricing is a perfect example because it is so cheap to implement, the primary difficulty should be political, in getting state legislatures to pass laws giving permission for cities to enact it. More American cities including San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle have shown interest but have shown extreme caution in part because they know how difficult the implementation will be. Instead of trusting legislators and representatives to work on behalf of city residents, needlessly complex and blunt regulations are stepping in the way and forcing us to continue to choke cities in idling car fumes.

Peter Kaplan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Peter Kaplan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Revenge Porn and Deep Fake Technology: The Latest Iteration of Online Abuse

Revenge Porn

The rise of the digital age has brought many advancements to our society. But it has also enabled new forms of online harassment and abuse. Revenge porn (otherwise referred to as image-based sexual abuse or nonconsensual pornography) is a type of gender-based abuse in which sexually explicit photos or videos are shared without the consent of those pictured. The prevalence of cell phones and user-generated content websites has turned revenge porn into a common phenomenon. While some legislation has been passed to meet this rising threat, technology has evolved to the point that many of these statutes no longer meet the challenge of the current environment. State legislators have left wide loopholes in their revenge porn statutes, and the rise in Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new brand of revenge porn missing entirely from state statutes. Furthermore, the federal government has so far failed to make revenge porn in any form a criminal offense.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

As of late 2022, forty-eight states and D.C. have enacted some form of revenge porn legislation (the two states that have yet to enact formal revenge porn statutes are Massachusetts and South Carolina). Some of these statutes criminalize revenge porn, while others allow victims to recover monetary damages under existing civil causes of action. While it is encouraging to see so many states act, efforts at the federal level have repeatedly encountered hurdles. Each time, those efforts stalled due to First Amendment concerns. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) crafted the Ending Nonconsensual Online user Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017 to make revenge porn a federal crime, but it died in committee and expired at the end of the 115th Congress. In 2018, Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced the Malicious Deep Fake Prohibition Act, criminalizing the creation or distribution of all fake electronic media records that appear realistic (essentially, banning deep fake technology altogether). The act expired at the end of 2018 with no cosponsors. In the past four years, Representative Yvette D. Clarke (D-NY) introduced the DEEP FAKES Accountability Act twice – the first in 2019 (H.R. 3230, which died in committee at the end of 2020) and the second in 2021 (H.R. 2395, which again died in committee at the beginning of 2023). In February 2023, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and John Cornyn (R-TX) introduced to the Senate Judiciary Committee the Stopping Harmful Image Exploitation and Limiting Distribution (SHIELD) Act (utilizing text originally introduced by Rep. Jackie Speier). Though it should be noted that the proposed SHIELD Act would not criminalize the rising threat of AI-generated pornographic images.

Rise of Deep Fake Technology

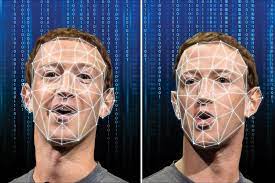

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

What began as sharing consensually obtained images beyond their intended viewers has evolved into more insidious and complex crimes. Hackers have started accessing private devices to steal intimate photos for the purpose of blackmailing victims with the threat of sharing those photos online. And the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has created a new type of revenge porn: deep fakes.

We have now entered a new phase of exploitation: AI-manufactured nude photos. Technology users can now utilize the photos of real people to create pornographic images and videos. There are two types of AI-generated images that relate to the problem of revenge porn: “deep fakes” and “nudified” images. Deep fakes are created when an AI program is “trained” on a reference subject. Uploaded reference photos and videos are “swapped” with target images, creating the illusion that the reference subject is saying or participating in actions that they never have. U.S. intelligence officials acknowledged deep fake technology in their annual “worldwide threat assessment” for its ability to create convincing (but false) images or videos that could influence political campaigns. In the context of revenge porn, pictures and videos of a victim can be manipulated into a convincing pornographic image or video. AI technology can also be used to “nudify” existing images. After uploading an image of a real person, a convincing nude photo can be generated using free applications and websites. While some of these apps have been banned or deleted (for example, DeepNude was shut down by its creator in 2019 after intense backlash), new apps pop up in their places.

This technology will undoubtedly exacerbate the prevalence and severity of revenge porn – with the line of what’s real and what’s generated blurring together, folks are more at risk of their image being exploited. And this technology is having a disproportionate impact on women. Sensity AI tracked online deep fake videos and found that 90%-95% of them are nonconsensual porn, and 90% of those are nonconsensual porn of women. This form of gender-based violence was recently on display when a high-profile male video game streamer accessed deep fake videos of his female colleagues and displayed them during a live stream.

This technology also creates a new legal problem: does a nude image have to be “real” for a victim to recover damages? In Ohio, for instance, it is a criminal offense to knowingly disseminate “an image of another person” who can “be identified form the image itself or from information displayed in connection with the image and the offender supplied the identifying information” when the person in the image is “in a state of nudity or is engaged in a sexual act.” It is currently unclear if an AI-generated nude image constitutes “an image of another person...” under the law. Cursory research did not unearth any lawsuits alleging the unauthorized use of personal images in AI-generated pornography. In fact, after becoming a victim to deep fake pornography herself, famed actress Scarlett Johansson told the Washington Post that she “thinks [litigation is] a useless pursuit, legally, mostly because the internet is a vast wormhole of darkness that eats itself.” However, in early 2023, artists have filed a class-action lawsuit against companies utilizing Stable Diffusion for copyright violations. This lawsuit may signal that unwilling participants in AI-generated content may could find relief in the legal system.

Some states have tackled head-on the issue of deep fake technology as it relates to revenge porn and sexual exploitation. In Virginia, it is a Class 1 misdemeanor for the unauthorized dissemination or selling of a sexually explicit video or image of another person created by any means whatsoever (emphasis added). The statute goes on to state that “another person” includes a person whose image was used in creating, adapting, or modifying a video or image with the intent to depict an actual person and who is recognizable as an actual person by the person's face, likeness, or other distinguishing characteristic. But this Virginia law is not without fault. The statute states that the image must be of a person’s genitalia, pubic area, buttocks, or breasts. Therefore, an image of a person in a compromising position or that is merely sexually suggestive would likely not be covered by this statute.

Current Remedies are Insufficient

Revenge porn victims often bring tort claims, which may include invasion of privacy, intrusion on seclusion, intentional/negligent infliction of emotional distress, defamation, and others. Specific revenge porn statutes also allow for civil recovery in some states. But revenge porn statutes have flaws. In an article authored by Professor Rebecca Defino, there are three commonly cited critiques to revenge porn statutes. The first is that many of these statutes have a malicious intent or illicit motive requirement, which requires prosecutors to prove a particular mens rea. (921; see the aforementioned Ohio statute; Missouri criminal statute; Okla. Stat. tit. 21, § 1040.13b(B)(2)). Second, many revenge porn statutes include a “harm” requirement, which is difficult to prove and requires victims to expose even more of their private life in a public arena. (921). And finally, the penalties are weak. (921). And even if a victim wins a case against a perpetrator, jail time for the perpetrator or small monetary settlements don’t provide victims what they often really desire – for their images to be taken off the Internet. The Netflix series called The Most Hated Man on the Internet shows the years long and deeply expensive journey to remove photos from a revenge porn website. While state revenge porn laws may assist victims with finding recourse, the process of removing images post-conviction can still be traumatizing and time-consuming.

While deep fake legislation is considered (or stalled) through state and federal governments, the private sector may be able to provide some solutions. A tool called “Take It Down” is funded by Meta Platforms (the owner of Facebook and Instagram) and operated by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The site allows anonymous individuals to create a digital “fingerprint” of real or deepfake image. That “fingerprint” is then uploaded to a database, which certain tech companies (including Facebook, Instagram, TikTok Yubo, OnlyFans, and Pornhub) have agreed to participate in, that will remove that image from their services. This technology is not without its own limitations. If the image is on a non-participating site (currently, Twitter has not committed to the project) or is sent via an encrypted platform (like WhatsApp), the image will not be taken down.

Additionally, if the image has been cropped, edited with a filter, turned into a meme, had an emoji added, or altered in other ways, the image is considered new and requires its own “fingerprint.”

While these are not easy problems to solve, the federal government can and should criminalize revenge porn, including AI-generated revenge porn. A federal statute would provide a stronger disincentive to create pornographic deep fakes through the threat of investigations by the FBI and prosecution by the Department of Justice. (927-928). Law professor Rebecca A. Delfino drafted the Pornographic Deepfake Criminalization Act, which makes the creation or distribution of pornographic deepfakes unlawful and allows the government to impose jail time and/or fines on defendants found guilty of the crime. (928-930). Perhaps more impactfully, the proposed act allows courts to issue the destruction of the image, compel content providers to remove the image, issue an injunction to prevent further distribution of the deep fake image, and award monetary damages to the victim. (930). The law is an imperfect tool in fighting against revenge porn and AI-generated pornographic deep fakes. But to the extent that legislators can provide additional support to victims, it is their obligation to do so.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.

Kara Kelleher graduated from Boston University School of Law with a juris doctor in May 2023.