Category: Health Law

Accelerated Public Health Modernization in Massachusetts

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and national movements for public health modernization, the Massachusetts Legislature tried to strengthen the Commonwealth’s public health during the summer of 2022. The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act (H.5014) (SAPHE 2.0) would have required local boards of health and regional health districts to comply with new minimum standards for public health service delivery. Governor Baker, however, proposed making the standards optional for municipalities, effectively killing the bill for the 2021-2022 legislative session. Fortunately, a new governor and legislature may provide some hope for this bill.

Public Health Modernization in Massachusetts

SAPHE 2.0 is a continuation of recent efforts by the Massachusetts Legislature to strengthen public health systems in the Commonwealth. In 2016, Governor Baker signed a legislative resolve establishing a special commission to “assess the effectiveness and efficiency of municipal and regional public health systems and to make recommendations regarding how to strengthen the delivery of public health services and preventive measures.” In 2019, the Special Commission on Local and Regional Public Health published a final report that found many local boards of health struggle to comply with public health service delivery statutes and regulations. More troubling, municipal compliance fell below national expectations set by frameworks like the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s 10 Essential Public Health Services, and the Public Health Accreditation Board’s Foundational Public Health Services that defines the minimum set of services and capabilities each health department required for its voluntary national public health accreditation program. The Special Commission noted that Massachusetts has 351 local boards of health–the largest number within any state, due in part to the Commonwealth’s emphasis on local autonomy–rather than the boards organized by county in other states. As a result, Massachusetts boards lack the capacity to deliver necessary public health services compared to larger health departments in other states, which have greater resources. The Special Commission recommended establishing minimum standards for public health in Massachusetts, which could help local boards of health achieve compliance with state requirements and then work toward accreditation, and facilitating cross-jurisdictional service sharing arrangements, among other reforms.

In April 2020, Governor Baker signed An Act Relative to Strengthening the Local and Regional Public Health System into law. The Act established the “State Action for Public Health Excellence” (SAPHE) program that aimed to “improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery of local public health services” in the Commonwealth through funding and technical assistance related to cross-jurisdictional collaboration, data sharing, workforce development, and other domains. The Act also charged DPH with defining minimum standards for foundational public health services in Massachusetts to enhance governmental public health performance. This legislation, however, made these standards voluntary and aspirational. The Act incentivized participation through a grant program to fund municipalities involved in planning, capacity building, and implementation of cross-jurisdictional sharing arrangements. The Department of Public Health currently funds 41 grantees representing 76% of municipalities across the state.

SAPHE 2.0

The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act, dubbed “SAPHE 2.0,” builds upon the 2020 law to continue strengthening public health systems in the Commonwealth. Critically, the bill would require municipalities to meet DPH’s minimum public health standards and provide material support to municipalities. SAPHE 2.0 would have also augmented the existing grant program in two ways: expanding the availability of competitive grants (establishment of shared service arrangements and expansion of existing arrangements) and providing grants and technical assistance to help health departments with “limited operation capacity” to meet requirements. The House and Senate unanimously passed the bill on July 29, 2022.

The Statewide Accelerated Public Health for Every Community Act, dubbed “SAPHE 2.0,” builds upon the 2020 law to continue strengthening public health systems in the Commonwealth. Critically, the bill would require municipalities to meet DPH’s minimum public health standards and provide material support to municipalities. SAPHE 2.0 would have also augmented the existing grant program in two ways: expanding the availability of competitive grants (establishment of shared service arrangements and expansion of existing arrangements) and providing grants and technical assistance to help health departments with “limited operation capacity” to meet requirements. The House and Senate unanimously passed the bill on July 29, 2022.

Proponents of SAPHE 2.0 support standardization of public health performance to ensure all Massachusetts residents receive comprehensive, high-quality public health services. A coalition led by the Massachusetts Public Health Association (MPHA) advocated for the bill, emphasizing that the decentralized approach to public health service delivery in the Commonwealth “leads to extreme variability across municipalities.” The MPHA also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated underlying public health inequities and called on the Legislature to “invest in creating a stronger, more equitable system that will provide essential public health protections to all residents.”

Executive Disapproval

In August 2022, Governor Charlie Baker declined to sign the bill and returned it to the Legislature with significant proposed amendments. Governor Baker supported the bill’s objective to “provide high-quality, coordinated and more uniform public health services across the Commonwealth” but expressed concern about the lack of guaranteed state funding to complement performance requirements for municipalities, which creates the potential for unfunded mandates. He also expressed concern that the bill lacked provisions requiring municipalities to maintain their own current levels of public health funding as a condition of receiving support from DPH. Accordingly, Governor Baker proposed to not mandate that local boards of health meet minimum public health standards, but instead permit them to opt in to receive funding from DPH to meet those standards while requiring them to maintain their existing municipal funding levels for public health services.

The MPHA criticized the proposed amendments, indicating they would “entrench the patchwork of municipal policies that makes our local public health system both ineffective and inequitable” (email newsletter on September 27, 2022). However, Governor Baker’s rejection of the bill reflects the primary motivations against it: the potential for local boards of health to receive no state funding to support their compliance with minimum standards. The Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) echoed Governor Baker’s sentiments, indicating support for “the intent of the legislation” but noting “strong concerns that the measure as written could impose a new annual unfunded mandate on municipalities.” Delivering testimony on the proposed bill, the MMA noted that “as written, H. 5104 does not mandate that the state meet its obligation to financially support the outlined goals. Instead, the state’s responsibilities would be subject to appropriation, while municipalities would not have that flexibility, and would be forced to fund the new costs imposed by the Department of Public Health.”

The Path Forward

SAPHE 2.0 is a microcosm of perennial public health concerns: how to deliver high-quality services and ensure equitable distributions of health burdens and benefits with limited resources. Governmental public health’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare structural health inequalities and emphasized the need for effective public health services and infrastructure, but also revealed logistical challenges inherent in forcing decentralized entities to act in tandem.

Although SAPHE 2.0 has been defeated in the short term, its longer-term prospects look promising: Governor Maura Healy took office in January 2023, and the Joint Committee on Public Health is considering a newly refiled version of the proposal. Public health advocates will continue to champion modernization efforts to advance the optimal health of all communities in Massachusetts.

Shannon Gonick anticipates receiving her juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

Shannon Gonick anticipates receiving her juris doctor from Boston University School of Law in May 2024.

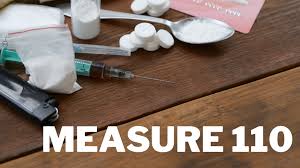

Decriminalize Everything? Oregon’s New Drug Laws

In November 2020, Oregon voters overwhelmingly decided to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of almost all hard drugs. Measure 110 went into effect on February 1, 2021. The legislation took a groundbreaking, albeit controversial step by reclassifying the possession of hard drugs. Offenses that were formally criminal misdemeanors, subjecting citizens to arrest, fines, and jail time, are now mere civil violations, subject only to a $100 civil citation, which can be avoided by participation in health assessments.

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

- 1 gram of heroin;

- 1 gram of MDMA;

- 2 grams of methamphetamine;

- 40 units of LSD;

- 12 grams of psilocybin;

- 40 units of methadone;

- 40 pills of oxycodone; and

- 2 grams of cocaine.

The measure further reduces the charge from a felony to a misdemeanor for simple possession of substances where the amount is:

- 1-3 grams of heroin;

- 1-4 grams of MDMA;

- 2-8 grams of methamphetamine; and

- 2-8 grams of cocaine.

As noted by Oregon State Policy Capt. Timothy Fox, “possession of larger amounts of drugs, manufacturing and distribution are still crimes.”

The law was predicted to have a drastic impact on yearly convictions for possession of controlled substances. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission estimated yearly convictions would decrease by a staggering 90.7%. The legislation comes approximately 50 years after President Richard Nixon famously declared his War on Drugs. While the drug war has been criticized as a racist, inhumane failure, Oregon’s recent legislation marks a significant, perhaps radical step towards restructuring the deeply flawed systems instituted over the past half century. This article will first explore the main arguments on either side of the debate regarding the wisdom and efficacy of Measure 110. Later, it will discuss some cautious conclusions and the broader implications of Measure 110 and how it might fit within the larger, national public debate regarding drug decriminalization.

The Promise

Proponents of Measure 110 see it as a much overdue remedial measure to a disastrous drug war that has done far more harm than good. Kassandra Frederique, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”), remarked on its passing, “Today, the first domino of our cruel and inhuman war on drugs has fallen, setting off what we expect to be a cascade of other efforts centering health over criminalization.” Supporters highlight the wisdom of shifting from a drug policy model that focuses on punishment, incarceration and criminalization to a more progressive model that sees drug use and addiction as a disease to be treated rather than a crime to be punished. From this perspective, substance use is better addressed by providing access to physical and mental healthcare and removing the stigmatization and obstacles that traditionally accompany drug charges such as the difficulty landing jobs and finding housing. “Criminalization keeps people in the shadows. It keeps people from seeking out help, from telling their doctors, from telling their family members that they have a problem,” says Mike Schmidt, district attorney for Oregon’s most populated county.

A key provision of Measure 110 earmarks a portion of cannabis tax revenues for improving and expanding the state’s treatment system, along with drug safety education and services. To date, Oregon has generated hundreds of millions of dollars for this purpose, distributed to at least 70 different organizations in 26 different counties, aimed primarily at helping providers expand services for people with low incomes and without insurance. This kind of investment is clearly a necessary part of shifting from a model oriented around the criminal justice system to a model oriented around healthcare. In addition, proponents of Measure 110 emphasize that decriminalization will ease racial disparities in drug arrests. For example, African American Oregonians are 2.5 times as likely to be convicted of a possession felony as whites. Without delving into the reasons behind this disparity, by reducing possession convictions overall decriminalization will reduce the negative effects on minority communities. Indeed, according to Theshia Naidoo, managing director for legal affairs at DPA, although the “information is not fully available yet . . . from the data we can see, there have been no drug possession arrests in the state since the decriminalization took effect.”

One major area of concern is implementation. Detractors question whether Oregon’s treatment system has the resources and functionality required to support such a fundamental shift away from the criminal justice system as the primary model for addressing drug use and executing drug policy. Are the resources provided by Measure 110 adequate to handle a corresponding substantial influx of people seeking treatment? Unfortunately, It is likely still too early to tell; but shifting from the criminal justice to the health care system is undoubtedly not going to happen overnight.

Relatedly, critics question whether a civil citation akin to a parking ticket will provide the adequate impetus and resources for users to seek help. Mike Marshall, co-founder and director of Oregon Recovers, worries that “the only way to get access to recovery services is by being arrested or interacting with the criminal justice system. Measure 110 took away that pathway.” Perhaps the threat of the criminal justice system provides users with the necessary motivation to seek treatment and the threat of a citation and potential fine is lacking in some critical respect. Decriminalization may ultimately limit access to treatment as fewer offenders are pushed into court-ordered programs. Decriminalization advocates counter that the criminal justice system’s pathway to treatment is flawed, biased and ineffectual, and point out that “on average a huge percentage [approximately 70 to 80 percent in Multnomah county] of those convicted of drug possession in the state were rearrested within three years.” Regardless, there is shockingly little data to determine what programs work best and no agreed upon set of metrics or benchmarks to judge program efficacy, either in Oregon or nationally.

The Verdict

Unfortunately, it’s likely too early to fairly assess whether Oregon’s remarkable drug policy transformation can be deemed a success. Part of this is because the transformation is still underway. Supporters of decriminalization point to Portugal as a reform model, which took more than two years to transition from a system centered around the criminal justice system to a healthcare model. Covid-19 is a another complication; Oregon’s detox clinics, recovery-focused nonprofits, and impatient facilities have been battered by the pandemic and related workforce shortages.

Nonetheless, Oregon’s bold efforts have seemingly inspired state level decriminalization efforts across the country as lawmakers in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont have all proposed similar decriminalization bills this year. The takeaway seems to be that decriminalization is a wise policy so long as recovery services are widely available. As Reginald Richardson, director of Oregon’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission, put it, “the use of criminal justice becomes a necessary proxy when you don’t have effective behavioral health services.” Overall, this kind of major shift in policy is daunting and will always involve overcoming unforeseen challenges, although hopefully not always to the extent of a global pandemic. Still, the Nixon-era drug policies has largely been an abject failure, and states like Oregon ought to be commended for trying, however imperfectly, to improve their approach.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Emergency Opportunity: Legislating Away Roe v. Wade During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

At the outset of the pandemic, many states banned “nonessential” medical procedures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and preserve PPE. However, several states took the opportunity to classify abortion as a “nonessential” procedure, making the surgery inaccessible. At the same time, the FDA deregulated the requirements for in-person prescription of many drugs, even opioids, but continued to heavily regulate medication related to abortion.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

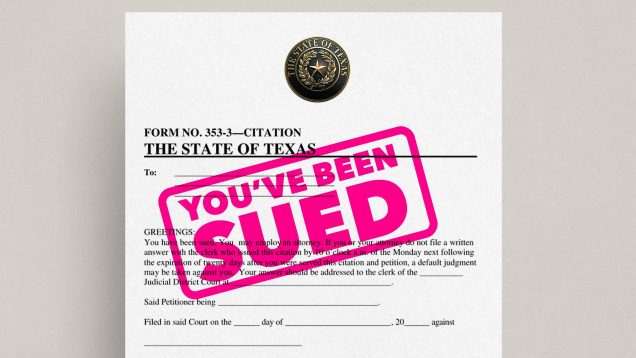

While the FDA was in legal battles over the requirements for medication abortion, conservative states began launching and defending legislation that restricted the right to a surgical abortion. During the 2021 session the Texas Legislature enacted the Texas Heartbeat Act, which bans abortion at the first sign of fetal heartbeat, which can be as early as 6 weeks. As BU Law and School of Public Health Professor Nicole Huberfeld pointed out, many women do not know they are pregnant within 6 weeks, and a “heartbeat” may mean no more than detecting an electrical pulse.

The key feature that has made Act a standout among anti-abortion bills is the citizen suit provision. The Act allows,

“any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local government entity in [the] state, may bring a civil action against any person who…performs or induces an abortion” or “aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.”

Enforcement is exclusively through private civil actions, a self-protecting mechanism that has been thought provoking for both the courts and the public. The lack of government enforcement leads many people to believe that there was no one to sue in order to challenge the legislation through judicial review. While the legislators may have thought this workaround clever, the Court recently held in Whole Women's Health v. Jackson that abortion providers may challenge the law by suing licensing officials. Still, the limited opportunity for judicial review may leave future constitutional rights vulnerable to this same evasive structure employed by the Texas legislation.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Just before announcing its limited decision allowing judicial review of the Heartbeat Act, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs centered around pre-pandemic Mississippi anti-abortion legislation, known as the “Gestational Age Act.” This Act directly confronts the holding of Planned Parenthood v. Casey by banning abortion after 15 weeks. It lacks the workaround that Texas employed but may nevertheless garner enough support from the Supreme Court to overturn the precedent from the Roe v. Wade line of cases. While Justice Roberts seemed inclined to uphold Roe but push back the line of imposing an undue burden to 15 weeks, other justices see the challenge as a call for an all-or nothing reversal of Roe. Overturning Roe would mean a complete change in the law surrounding abortion not just because of overturning common law precedent, but also because many states have drafted trigger laws, that specify that if Roe is overturned, abortion is automatically illegal in the state.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

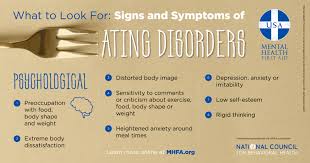

Never Too Early to Save a Child’s Life: Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act of 2020

Eating disorders have the second highest mortality rate of any mental illness, second only to opioid overdose. 1 in 5 women (19.7%) and 1 in 7 men (14.3%) will suffer from an eating disorder. Not only are eating disorders potentially life-threatening, eating disorders can carry devastating long-term consequences on both physical and mental “health, productivity, and relationships.” These disorders can also be indications of co-occurring mental conditions that will worsen over time without proper treatment. Early screening and intervention are imperative to addressing and abating these long-term effects. Congress can address this difficult public health problem by passing the Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act.

Eating disorders can affect all individuals regardless of body size, age, gender, or race; however, BIPOC teenagers, LGBTQ+ individuals, disabled individuals, overweight individuals, athletes, and veterans are at an increased risk of developing an eating disorder. The majority of eating disorders develop during adolescence and young adulthood, with high recurring rates later in life. Targeted prevention efforts for young individuals remain critical to reduce eating disorder-related mortality and complications.

Eating disorders can affect all individuals regardless of body size, age, gender, or race; however, BIPOC teenagers, LGBTQ+ individuals, disabled individuals, overweight individuals, athletes, and veterans are at an increased risk of developing an eating disorder. The majority of eating disorders develop during adolescence and young adulthood, with high recurring rates later in life. Targeted prevention efforts for young individuals remain critical to reduce eating disorder-related mortality and complications.

Disordered eating and body dissatisfaction, common risk-factors associated with eating disorders, are highly prevalent among children and young adults. Expectations to be thin begin at a very young age: 42% of 1st to 3rd grade girls desire to be thinner and 81% of 10 year old children report fears of being fat. Subsequently, dieting begins at a very young age: 46% of children ages 9-11 report that they are “sometimes” or “very often” on diets; 35-57% of adolescent girls engage in dangerous behaviors such as “crash dieting, fasting, self-induced vomiting, diet pills, or laxatives”; and 91% of college-aged women report dieting to control their weight. The American Academy of Pediatrics strongly discourages young people from dieting, especially without active involvement and support from family and clinical supervision by a pediatrician. Studies show that dieting is counterproductive to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and “teenagers with no weight problem will gain weight due to weight loss attempts." Most importantly, however, dieting can predispose individuals to eating disorders and reinforce the “normative discontent” around body dissatisfaction that greatly increases maladaptive health behaviors and psychological stress.

Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act

To address this alarming public health issue, Representative Alma Adams (D-NC-12) and Representative Vicky Hartzler (R-MO-04) introduced the bipartisan Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act of 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives on May 6, 2020. The bill is currently referred to the House Committee on Education and Labor. If passed, this Act will require school districts to develop school nutrition programs and physical activity programs in a way that will help prevent disordered eating and eating disorders. The goal of the Act is to improve overall health outcomes for all children. In the bill’s press release, Representative Adams noted the urgency of passing this legislation stating that “[a]s students across the country face disruptions, stress, and anxiety due to COVID-19, all of which exacerbate mental illnesses like eating disorders, the need for this legislation grows increasingly clear.”

The Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act has the support of the National Eating Disorders Association (“NEDA”), the largest nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting those affected by eating disorders. Chevese Turner, NEDA’s Chief Strategy & Policy Officer, advocated for the legislation stating that it “is an important step forward in eating disorders prevention and early identification efforts . . . Schools are uniquely positioned to play a part in this increasingly significant public health issue that has the second highest mortality rate of any mental health disorder and will affect over 30 million people in their lifetime in the US alone.”

The bill specifically requires local educational agencies that participate in school lunch or breakfast programs to “include goals for  reducing disordered eating in children of all sizes in their local school wellness policies.” The Department of Agriculture will be required to provide information and technical assistance to local educational agencies, school food authorities, school health professions, and state educational agencies. This assistance must promote eating disorder prevention, encourage eating disorder screening, and help establish healthy school environments. One of the most important aspects of this bill is that in developing, implementing, and reviewing school wellness policies, local educational agencies must involve registered dietitians and licensed mental health professionals.

reducing disordered eating in children of all sizes in their local school wellness policies.” The Department of Agriculture will be required to provide information and technical assistance to local educational agencies, school food authorities, school health professions, and state educational agencies. This assistance must promote eating disorder prevention, encourage eating disorder screening, and help establish healthy school environments. One of the most important aspects of this bill is that in developing, implementing, and reviewing school wellness policies, local educational agencies must involve registered dietitians and licensed mental health professionals.

The Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act could be an important catalyst to implementing eating disorder prevention and screening programs in schools across the United States. It is vital that the bill maintains its requirement that registered dietitians and licensed mental health professionals be involved in the creation of school policies. In addition, for the intended goals of this legislation to be successful, these registered dietitians and licensed mental health professionals need to specialize in eating disorder treatment, a highly delicate and nuanced field.

Not all dietitians and mental health professionals understand the severity of weight-bias in the treatment of eating disorders. Studies show that even gentle conversations discussing “healthy eating” can lead children to interpret the message very strictly leading to the adoption of rigid rules regarding good foods versus bad foods. Programs and policies developed to address disordered eating and eating disorders need to be carefully crafted to avoid unintentional consequences stemming from discussing weight, eating, and exercise in a way that could lead a child to develop maladaptive behaviors. Prevention efforts should take the focus away from weight and healthy eating, and instead focus on joyful movement and body acceptance.

The Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act is a positive step towards addressing a significant public health problem. The Act could help a large portion of the next generation avoid developing a life-threatening and devastating mental illness. It is imperative, however, that clinicians specializing in eating disorders remain a significant part of the conversation when schools attempt to implement these prevention programs. Discussing weight, eating, or exercise is a delicate subject that can sometimes cause more harm than good. With the right training and policies in place, schools can change the narrative around weight and body image and make a positive impact on the overall health of its students. The Eating Disorders Prevention in Schools Act can help make this vision a reality.

Jessa Boubker graduated from Boston University School of Law and Boston University School of Public Health with a JD/MPH in May 2021.

Jessa Boubker graduated from Boston University School of Law and Boston University School of Public Health with a JD/MPH in May 2021.

Should Foster Parents Unionize?

Foster care reform rarely makes it into dinner-table discussions of hot political happenings, but Massachusetts State Representative Tricia Farley-Bouvier of the Berkshires may change that with two bills she introduced this session: one creates a Foster Parent Bill of Rights, and the other allows foster parents to collectively bargain– raising the specter of a foster parent union.

The legislation addresses widespread problems in how the Department of Children and Families (DCF) deals with foster parents. “If there was a totem pole of regard and respect, when in the child welfare agency, [foster parents] are at the very bottom of that totem pole,” explained Representative Farley-Bouvier. The most egregious area of concern is DCF’s failure to communicate essential information like reimbursement rates, court dates, behavioral issues and even a child’s allergies and medications, a potentially dangerous omission that Farley-Bouvier says “happens more often than you would imagine.” Consider the alarming experience of one parent, Rachel, who told DCF she could not manage a child with severe behavioral problems. DCF nevertheless placed a child with her who had a history of a “violent temper,” including throwing chairs at school and threatening other children. DCF had concealed these behavioral issues from Rachel, flagging only that the child had hygiene issues. While “it’s true that in the months [the child] lived in Rachel’s home she smeared feces on the wall, that was one of the less frightening incidents.” In another troubling case, DCF failed to share with a parent that a twelve-year-old boy placed with her had a history of sexual predation; he abused her four-year-old daughter.

The Foster Parent Bill of Rights aims to address communication failures and other issues, and while DCF did not publicly comment on the legislation it “collaborated with the legislature on and supports” it. Under the bill DCF must:

- Not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age or physical ability

- Keep foster parent information confidential

- Develop a standardized training, as the current thirty-hour course parents are given is criticized for leaving them “ill-prepared to handle the complexity and severity” of emotional, physical, and psychological they see

- Share information to “the greatest extent possible” on the physical and behavioral health of the child, their educational needs, and daily routine

- Inform foster parents of all payments and sources of financial suport they may be entitled to, to address the common issue of families not being told what expenses they will be reimbursed for

- Consult with foster parents in planning visitation

- Provide no less than ten days of paid respite care per year

- Establish a 24 hour emergency hotline

- Not retaliate against parents who file complaints against DCF, and

- Provide foster parents the opportunity to leave helpful notes for the next parent (for example “She’s afraid of the dark, but a night light comforts her. Her brother loves chicken nuggets.”).

What the bill does not do is set specific standards or allow for foster parent input on critical items like training or reimbursement rates. Foster parents would still need to advocate for their needs on an individual basis with DCF.

Farley-Bouvier’s other bill addresses this power imbalance by giving foster parents the right to collective bargaining. The bill classifies foster parents as public employees, but solely for this purpose—they would not receive a salary, be eligible for benefits, retirement contributions, or worker’s comp, and would not be permitted to strike. The bill directs DCF and a foster parent union to bargain on:

- The responsibilities of DCF to foster parents

- Education and training opportunities

- Recruitment and retention of foster parents

- Payment rates and other reimbursement issues, including for property losses caused by children, and extracurricular or social costs

- Access to special education, respite care, and behavioral health services (which are sorely needed but currently take months to access)

- Inclusion of foster parents in developing service plans for children

Retention of qualified foster parents is especially important, as too many children are placed in unsafe, abusive foster homes. In 2016, thirty-five foster children in Massachusetts died, and hundreds were neglected or abused. Two thousand families stopped participating in the foster system in the last five years, which is almost as many as the number currently participating. DCF does not track why parents stop participating, but research shows that lack of respect, insufficient training, and reimbursement rates that are far below actual costs contribute to a national turnover rate of fifty percent.

Unsurprisingly, the bill faces pushback. Dispute within the foster care advocacy group Massachusetts Alliance for Families (MAFF) illustrates both sides of the debate: former president Cheryl Haddad supports a union because it is “very unreasonable to ask these volunteers who help take care of children to go to the legislature to ask them for services. It's crazy,” while current president Catherine Twiraga says “I didn't become a foster parent to get a job, I became a foster parent to help children. So I don't see how it can be one in the same. I've had jobs where I was an employee and that's not how I approach being a foster parent.”

Conservative groups traditionally opposed to unions have seized on Twiraga’s argument, as demonstrated in a WSJ opinion cleverly titled “Clean Your Room or I’ll Call my Union Rep”. Twiraga is quoted within, saying a union “will only reinforce the stereotype that we are doing it for money,” and that she is “baffled by the idea that the union will be negotiating for more vacation time for foster parents,” asking whether that means she can take Christmas off. Her comparison of respite care to vacation is disingenuous. Foster care is not a 9-5 job but a 24/7 endeavor replete with stresses not found in an office job, and parents are reimbursed only for costs, not paid a wage for their work. As a foster parent herself, Twiraga must know that respite care is a critical service that allows foster parents to deal with family emergencies, their own illness, or the emotional burnout that contributes to high turnover rates. But Twiraga’s arguments display a belief deeply held by many: foster parents should be selfless volunteers motivated only by altruism, and negotiating for better conditions means they are money-grubbers.

Even—perhaps especially—foster parents motivated by altruism should be fairly reimbursed for costs incurred, given plentiful training, and be able to hold DCF accountable for its responsibilities. While a desire to help children may be necessary to succeed as a foster parent, on its own, “altruism is no longer enough to recruit and retain foster parents.” Unions and care work are not mutually exclusive—helping professions like home health aides and childcare workers have successfully unionized. Improving conditions for care workers, paid or volunteer, can only result in benefits for the people in their charge. Those foster parents with good motives are precisely the ones the system needs most to retain. A union could equalize the power imbalance between foster parents and DCF to bargain for much-needed changes that could keep parents from leaving the system. If foster parents are given the resources they need to succeed in the system, children in foster care in Massachusetts stand to benefit a great deal.

Brianna Isaacson graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Brianna Isaacson graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Wearables and the FDA: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

When the COVID-19 pandemic upended the entire world in March 2020, many industries were thrown in chaos. With the limitations on capacity in gyms across many states, technologies such as the Apple Watch or Fitbit (collectively called “Wearables”) became increasingly popular. Wearables are devices that track activities and record information about the person’s movements using sensors. Early models had simple uses like counting a user’s steps throughout the day. As the devices became more sophisticated, wearables quickly transformed into powerful tools that could monitor physical activity, sleep patterns, calories burned, and even blood pressure.

FDA Regulation of Medical Devices

In 1938, Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that provided the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) the authority to regulate medical devices. According to the Medical Device Regulation Act, the FDA regulates devices based on the potential risk of harm from the device, classifying devices as Class I, Class II, and Class III. Class I devices have a low risk of harm to patients while Class III devices are high risk. As the class of device increases, the FDA imposes more regulatory controls to ensure the device is safe and effective. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act (the “Cures Act”) clarified that certain digital software intended for low-risk general wellness purposes should be excluded from the statutory definition of a device. Low-risk general wellness software is defined as software features intended to help consumers maintain or encourage a healthy lifestyle and is not related to the diagnosis or treatment of a disease or condition.

In 1938, Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that provided the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) the authority to regulate medical devices. According to the Medical Device Regulation Act, the FDA regulates devices based on the potential risk of harm from the device, classifying devices as Class I, Class II, and Class III. Class I devices have a low risk of harm to patients while Class III devices are high risk. As the class of device increases, the FDA imposes more regulatory controls to ensure the device is safe and effective. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act (the “Cures Act”) clarified that certain digital software intended for low-risk general wellness purposes should be excluded from the statutory definition of a device. Low-risk general wellness software is defined as software features intended to help consumers maintain or encourage a healthy lifestyle and is not related to the diagnosis or treatment of a disease or condition.

However, a device’s intended use can be hard to define. Intended use refers to the objective aim for the purpose of device. The FDA has a longstanding policy that all relevant evidence can be used to determine intended use including labeling, advertisements, and oral and written statements. However, companies use different marketing tactics, including both general and very specific messaging, to make their devices standout which can leave the intended use of a device up to interpretation.

Wearables and FDA regulation

As the capabilities of wearables increased, the FDA has grappled with how to regulate the new technology. Originally, wearables  were not considered medical devices unless they made claims about treating specific diseases or conditions. However, as the technology of wearables advanced, the FDA regulated some new features. For instance, Apple released an EKG feature on its watch to detect Atrial Fibrillation. Since it was meant to detect Atrial Fibrillation (an irregular heartbeat), Apple could not classify the feature as a general wellness device and the feature needed to be FDA cleared.

were not considered medical devices unless they made claims about treating specific diseases or conditions. However, as the technology of wearables advanced, the FDA regulated some new features. For instance, Apple released an EKG feature on its watch to detect Atrial Fibrillation. Since it was meant to detect Atrial Fibrillation (an irregular heartbeat), Apple could not classify the feature as a general wellness device and the feature needed to be FDA cleared.

Wearables and the COVID-19 pandemic

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, a N.Y. Times Op-Ed advocated for the general public to use pulse oximeters to monitor their blood oxygen levels in hopes of detecting potential COVID-19 cases earlier. In September, Apple released a new pulse oximeter feature for its watch to allow people to monitor their blood oxygen levels. However, unlike the EKG feature, Apple marketed the new feature as a general wellness device. This allowed Apple to avoid FDA regulation. Any mention by Apple of the device’s ability to detect, diagnose or treat a specific condition or disease would mean that the device is subject to FDA regulation. To avoid being subject to FDA regulation, during the launch video, Apple executives discussed the general importance of pulse oximeters in detecting COVID-19, failing to mention the new feature was not FDA cleared for the purpose of detecting COVID-19.

The FDA should regulate these new wearable features because these new functions are not general wellness low-risk devices. Although Apple did not directly promote the pulse oximeter feature to detect COVID-19, Apple hints that the device can do this despite the lack of FDA clearance or approval. If the FDA lets this type of marketing go unchecked, they risk a “regulatory arbitrage” where companies design their devices to avoid costly clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy and instead promote devices as purely general wellness devices. Not only is this dangerous to consumers because the devices may not be effective for those purposes, but society may suffer as companies settle for simple devices rather than pushing to invent new technology.

In terms of risk level, the pulse oximeter is not low risk for two reasons. First, the FDA has released guidance documents stating that stand alone pulse oximeters should be classified as a Class II device. As a Class II device, the FDA considers pulse oximeters as medium to moderate risk devices. A feature in the Apple Watch (or other wearables) should not be subject to less regulation simply because it is part of a larger device. Second, the device could affect people’s decision to seek care despite the device’s documented inaccuracy. If the pulse oximeter feature shows normal blood oxygen levels, but in reality, a person has low blood oxygen levels, they might delay seeking care. This delay could have deadly consequences. Additionally, the device could mistakenly show low blood oxygen levels causing additional anxiety and emotional anguish during a period that has been incredibly hard for many people’s mental health.

The FDA’s role is to ensure medical devices on the market are safe and effective. However, some people argue that the FDA unnecessarily slows down products’ ability to enter the market stifling innovation. In this situation, some argue that a potentially helpful device, like the pulse oximeter on the Apple Watch, should reach the market as soon as possible and that market forces are sufficient to regulate new devices. The FDA is exploring this option through the launch of the Digital Health Software Precertification Program. Unlike the current system, the program would certify companies based on their comprehensive development and validation processes rather than focusing on specific products. Although this program would allow the products to get to market quicker, the program is still being evaluated. Until this program is proven effective, the FDA should not cede regulatory power to companies especially during a global pandemic.

Moving Forward

Although the FDA could exercise its regulatory power over the wearable industry, a more permanent solution is to update the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Many products on the market, especially in the wearable industry, include different software features that could qualify as medical devices. Our laws regulating medical devices should be updated to reflect this possibility. Congress should clarify that any software feature, whether included in a larger device or not, will be regulated based on its intended uses and risk level to consumers. Additionally, Congress should codify the FDA’s longstanding policy of using all available evidence and define intended use. This will keep manufacturers of products honest about the capabilities of a feature so they do not market a type of software generally for a specific purpose that it may not be FDA approved or cleared for.

Alex Maulden anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Alex Maulden anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act

A Pandemic Silver Lining: Health Care Reform in Massachusetts

On January 1, 2021, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed into law an omnibus healthcare law called “An Act Promoting A Resilient Health Care System That Puts Patients First.” This multi-faceted healthcare law addresses various healthcare issues that have come to light or been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes the codification of some emergency orders from the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic that helped loosen restrictions in order to provide easier access to healthcare. Thematically, the main provisions of the bill include: (1) surprise billing; (2) practitioner scope of practice; (3) telehealth; and (4) healthcare accessibility. First, each of these provisions will be discussed. Then, possible shortcomings of the law will be considered. To conclude, we must question why it took a pandemic to bring commonsense change to Massachusetts healthcare.

Surprise Billing

The act addresses so-called surprise medical bills, where the charges are higher than the insured individual expected, likely  because they inadvertently received care from an out-of-network provider. This can happen if: (1) the insured patient receives care from an out-of-network provider in an emergency situation where the patient has no ability to select the care; or (2) the insured patient receives pre-planned care from an in-network facility, but the services are provided by an out-of-network provider.

because they inadvertently received care from an out-of-network provider. This can happen if: (1) the insured patient receives care from an out-of-network provider in an emergency situation where the patient has no ability to select the care; or (2) the insured patient receives pre-planned care from an in-network facility, but the services are provided by an out-of-network provider.

Surprise medical billing has been in the spotlight at both state and federal levels. In late 2020, President Trump signed the No Surprises Act which holds consumers harmless from the cost of unanticipated out-of-network medical bills. The act applies to nearly all private health plans offered by employers, as well as insurance policies offered through the federal marketplace, but does not take effect until January 1, 2022. In addition, the federal law does not preempt state law, but instead defers to state requirements around surprise billing. To date, at the state level, 27 states have passed consumer protection laws against surprise medical bills and, in 2020, 5 additional states have passed and will enact or have enacted surprise billing legislation.

The Massachusetts law: (1) requires providers to disclose if they are out-of-network prior to the patient’s admission; (2) requires providers, upon request, to share the amount that the patient will be charged for admission, a procedure, or a service, including costs for services done by an out-of-network provider; (3) requires providers to notify patients if the patient is being referred to an out-of-network provider; (4) prohibits providers from billing insured patients in excess of the typical, applicable coinsurance, copayment, or deductible that would have been charged if services were provided by an in-network provider; and (5) directs the Secretary of the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, the Health Policy Commission, Center for Health Information and Analytics, and Division of Insurance to recommend a default rate for out-of-network billing by September 2021.

However, even after the expanded protections against surprise medical billing, Massachusetts is still categorized as a state with partial balance billing protections from The Commonwealth Fund and as a state with a limited approach to surprise billing from The Kaiser Family Foundation. Both organizations have found that to be considered comprehensive, a state must additionally: (1) hold patients harmless, (2) create a dispute resolution process between the insurer and provider; (3) provide a formula that the insurer must apply when determining how much to pay an out-of-network provider; and (4) apply in specific care settings, like emergency departments. The current Massachusetts law’s direction to recommend a default rate for billing is a step in the right direction towards a comprehensive approach to surprise medical billing, but will need to be taken further.

Practitioner Scope of Practice

The Massachusetts act also makes statutory changes to the scope of practice for several categories of health care practitioners. The act codified previous Department of Public Health emergency administrative orders allowing advanced practice registered nurses (“APRNs”), including nurse anesthetists, nurse practitioners, and psychiatric nurse mental health clinical specialists to have: (1) expanded practice at mental health facilities; and (2) independent prescriptive practice. To qualify for the expanded scope of practice provision, the APRNs must meet specific qualifications, including at least two previous years of supervised practice under a physician. The emergency orders were in response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but will now extend past the pandemic due to the act.

The act also expands scope of practice for optometrists. Optometrists now have prescriptive authority and can treat glaucoma. The act also creates an option for reciprocity for optometrists with licensure in other states. Additionally, psychiatric nurse mental health clinical specialists have expanded authority for determinations on psychiatric evaluations, restraints, and hospitalizations. Finally, the act recognizes the role of pharmacists, who are now able to integrate with coordinated care teams to review medications and identify areas of clinical improvement.

Telehealth

The act also codifies earlier COVID-19-related emergency changes to telemedicine. At the federal level, the Department of Health and Human Services made access to telehealth easier through guidance on HIPAA flexibility, allowing entities to file waivers with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services related to originating sites, cross-state telemedicine, provision of care to new patients through telehealth, and billing for telehealth services as though they were in-person. At the state level, a Massachusetts emergency order required insurers to cover all medically necessary telehealth services and required that these services be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person services, creating pay parity between telehealth and in-person visits.

The new Massachusetts act: (1) updates the definition of “telehealth” to include audio-only services; (2) eliminates the requirement for providers to show barriers to in-person care or limitations on location settings in order to access telehealth services; (3) prohibits insurers from declining coverage of healthcare services solely because the services were provided through telehealth as long as the healthcare service would otherwise have been covered in-person and it may be appropriately provided through telehealth; (4) requires pay parity for copays and deductibles for in-person and telehealth services, plus extends the temporary emergency order for pay parity for 90 days after the expiration of the COVID-19 state of emergency in Massachusetts; and (5) requires licensed hospitals, insurers, health maintenance organizations (“HMOs”), and the Executive Office of Health and Human Services to ensure that the pay rate for in-network providers of behavioral health services and chronic disease management services provided via telehealth be no less than the rate of payment for the same services when provided in person.

The new Massachusetts act: (1) updates the definition of “telehealth” to include audio-only services; (2) eliminates the requirement for providers to show barriers to in-person care or limitations on location settings in order to access telehealth services; (3) prohibits insurers from declining coverage of healthcare services solely because the services were provided through telehealth as long as the healthcare service would otherwise have been covered in-person and it may be appropriately provided through telehealth; (4) requires pay parity for copays and deductibles for in-person and telehealth services, plus extends the temporary emergency order for pay parity for 90 days after the expiration of the COVID-19 state of emergency in Massachusetts; and (5) requires licensed hospitals, insurers, health maintenance organizations (“HMOs”), and the Executive Office of Health and Human Services to ensure that the pay rate for in-network providers of behavioral health services and chronic disease management services provided via telehealth be no less than the rate of payment for the same services when provided in person.

Healthcare Accessibility

The act’s provisions related to healthcare accessibility are wide and varied. The act addresses broad healthcare issues that have posed problems for many years, but have been exacerbated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two relevant provisions include: (1) Massachusetts Medicaid or MassHealth patients no longer need to seek referrals from a primary care provider to an urgent care visit; and (2) all insurers, including MassHealth, must cover all COVID-19 related emergency, inpatient, and cognitive rehabilitation services, plus they must cover all medically necessary COVID-19 testing.

Conclusion

Though this bill tackles many issues that public health experts have promoted for years, there are always additional healthcare problems to be solved. Governor Baker notes that he hopes, in future years, to focus on addiction services, behavioral health, primary care and geriatric services, and prescription drug prices.

However, the law is not without its detractors. The Massachusetts Medical Society, for instance, while applauding many provisions, took issue with: (1) the added burden on physicians to notify patients about possible out-of-network care and billing; (2) the general increased scope of practice for nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurse mental health clinical specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists, arguing that a physician-led team is the best care team; and (3) the lack of permanent pay parity for all telehealth services. Thus, it is likely that the law will face some pushback from physicians. Additionally, as seen with the surprise billing provisions, there are ways that the state could have gone further to provide more patient protection and access to healthcare.

The question remains, however. Why did it take a pandemic to bring about common-sense healthcare changes to Massachusetts? The answer, I think, lies in the shared experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. Governor Charlie Baker, while signing the bill into law, said that the “silver lining” of the pandemic has been that healthcare reforms were tested and proved effective, generating momentum to create long-lasting change for the future. There’s more to it than that. Even before the pandemic, we’ve all seen and heard from friends and family that the healthcare system is broken and now we’ve all seen how the pandemic has only exacerbated that. Massachusetts residents and members of the legislature have seen how barriers to care - like difficulties paying off a surprise medical bill and having to go into medical debt, difficulties getting an appointment with your physician because they’re busy with the pandemic but also then being unable to see an APRN for care, or an inability to access telehealth when you’re scared of going for in-person care in the midst of a pandemic - has affected our loved ones throughout the pandemic. It’s this shared experience and now shared understanding of the hardships of our existing healthcare system that drove the healthcare reforms and success of this bill.

Megha Mathur anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Megha Mathur anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

There’s No Such Thing as Sex Without Consent

On January 16, 2020, the Massachusetts Senate passed S.2475 “An Act Relative to Healthy Youth,” which creates mandatory guidelines schools must follow when implementing their sex education curricula. This does not require schools to adopt a curriculum, and there is an opt-out provision for parents who do not wish their children to receive this education. Still, the bill requires medically accurate information be shared, that a comprehensive view of sex education be taught that goes beyond abstinence-only education, and, perhaps most importantly, the bill requires schools teach students about consent, boundaries, and healthy and safe relationships. Unfortunately, the 2020 legislative session came to an end with the bill stuck in the House Committee on Ways and Means.

Sex Education in the United States

In the United States, sex education started as a movement to discourage masturbation in young men, and encourage abstinence before marriage. While sex education started to spring up more in public schools during the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s when the the American Medical Association and public health officials first advocated a standardized curriculum. The 1960s saw religious and conservative groups attack sex education, asserting that teaching youths about sex would make sexual engagement more likely. In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS health crisis led many officials, backed by federal funding, to require abstinence-only sex education in schools.

before marriage. While sex education started to spring up more in public schools during the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s when the the American Medical Association and public health officials first advocated a standardized curriculum. The 1960s saw religious and conservative groups attack sex education, asserting that teaching youths about sex would make sexual engagement more likely. In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS health crisis led many officials, backed by federal funding, to require abstinence-only sex education in schools.

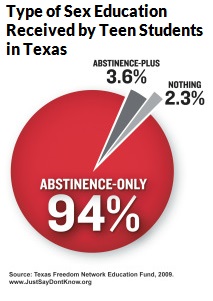

By 2009, the federal government was putting $170 million per year into these George H.W. Bush era programs. Under President Obama, the federal government continued funding abstinence-only programs, but also introduced a more comprehensive sex-education approach in an effort to reduce teen pregnancy. The Trump administration then gutted the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, restricting federal funding to abstinence-only programs.

On the state level, 37 states require sex education programs to cover abstinence and 27 of those require prioritizing abstinence.  Students who attend schools with less funding are more likely to receive abstinence-only education, leading to a correlation between socioeconomic status and an increase in teen pregnancy, STDs, and sexual violence.

Students who attend schools with less funding are more likely to receive abstinence-only education, leading to a correlation between socioeconomic status and an increase in teen pregnancy, STDs, and sexual violence.

Currently, only 8 states and Washington D.C. require students learn about consent. Of these, seven passed their requirements within the last four years. In just 2019, four jurisdictions passed consent education requirements and nine more states introduced similar legislation.

The Importance of Consent Education

Sex is not sex without consent – it’s rape.

A Columbia University study indicated that those who received training in how to refuse sexual advances were less likely to be sexually assaulted in college. There was no similar correlation between abstinence-only sex education and sexual assault. Equipping students with the ability to set their own boundaries is important, but teaching students to recognize and respect those boundaries in others is just as necessary to prevent sexual violence. Merely giving students the tools to help them potentially get out of a situation they don’t want to be in is not enough, because it does not express the importance of consent in sexual interactions. As long as people fail to recognize and respect the consent of others, there will always be uncomfortable or dangerous situations to try to get out of – it’s mopping up the water from the overflowing sink without turning off the tap.

For young children, consent education reassures them that they have a say in what happens to their bodies (something many children are not aware of), and it teaches them to respect other peoples’ choices, as well. As students age, understanding consent as a concept allows them to form fundamental understandings of what healthy relationships with others look like. Beyond a reduction in sexual violence and misconduct, these are important life-skills that reach far beyond sexual situations.

The Opposition

There is still support for abstinence-only sex education in many parts of the country, and consent education is often seen as condoning sex. Unfortunately, resisting consent education works against abstinence-only goals by not providing students with the tools needed to establish healthy boundaries and respect for each other’s physical space. These skills are key for both those who wish to remain abstinent until marriage and for those who engaging in sex.

condoning sex. Unfortunately, resisting consent education works against abstinence-only goals by not providing students with the tools needed to establish healthy boundaries and respect for each other’s physical space. These skills are key for both those who wish to remain abstinent until marriage and for those who engaging in sex.

Some of those who oppose consent education, especially for younger students, worry that the subject matter may be too mature, but consent education does not have to be presented along with sex education for younger students to be effective. Consent is ultimately about permission, which is a concept children can easily grasp. For example, sharing and borrowing things involves consent. Additionally, teaching consent around hugging is a way to instill physical boundaries in children.

Looking Forward

West Virginia, Rhode Island, and D.C. have all adopted comprehensive legislation on consent education. These states require consent education based on the student’s age, introduce the concept of consent to younger children while assuaging some of the opponent’s concerns.

Harvard’s Graduate School of Education created a consent education model based on suggestions from educators across the country. The model proposed laying a foundation of consent and boundary building behaviors in younger children, and then including sex in the conversation for older students.

The Harvard model also recognizes that consent education should not be limited to straight boys but that anyone can perpetrate sexual violence and misconduct. Just as socioeconomic factors play a role in who receives comprehensive sex education, individuals holding certain identities are disparately impacted by sexual violence and students need to be aware of these inequities as they learn to navigate sex and consent.

Every school should adopt some form of consent education both before and during sex education. Otherwise, we will continue to endure a society that fails to respect the boundaries and choices of others. The Massachusetts Senate passed bill was a step in the right direction. Hopefully, the bill will become law during this new legislative session.

Alexa Weyrick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Alexa Weyrick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Real Cost of COVID-19: The Fractured Health Care System

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has uprooted the very foundation everyday life, turning socialization into a moral evil, and weaponizing safety precautions as political propaganda. These clear immediate costs, amounting in the loss of life, jobs, and social pleasures, are merely the surface to a rather elaborate system of institutional market failures that are bound to follow. While the coronavirus promptly began a long-awaited economic recession, forcing more than 31 million people in the United States to file for unemployment insurance, there has been a catastrophic loss of employer based health insurance coverage for many individuals, leaving only those who are eligible and qualified to move over to Medicaid or other subsidized health insurance policies. Unfortunately many have found themselves stuck in what is known as the “coverage gap,” with health care access becoming a novelty when its demand is at an all-time high.

Hospital and Insurance Coverage Crisis

Hospitals are largely believed to be price inelastic institutions, where demand for health services will remain constant, and funds will continuously keep providers operational even during economic recessions. While one might think that the COVID-19 public

health crisis would drive health care consumption, benefiting hospitals, it has actually been quite the opposite. Demand for healthcare services has been primarily for expensive specialized care, imposing high out-of-pocket expenses on individuals who are treated for COVID-19, and has further shifted from routine visits, seeing reductions as high as 60%.. The increased costs in specialized care, combined with the decrease in less costly routine care has not been the only shock to the health care industry. Additionally, by April of 2020, 1.4 million health care jobs were lost to enable hospitals to produce positive profit margins, creating staffing shortages across many US hospitals. This, paired with over 40 million Americans losing their jobs and shifting to subsidized healthcare and Medicaid, has created a loss of up to 20% of the commercial insurance market. By decreasing those covered by commercial insurance plans, cost aversion behaviors will decline health care usage, and those who are eligible will move over to Medicaid. Shifting from private to public insurance at this rate will cost Hospitals $95 billion in annual revenue. While Hospitals are experiencing adverse pressure, threatening what was believed to be recession proof industry, it is merely one of the many cracks that make up an unsustainable health care system.

The CARES Act and FFCRA’s Truncated Effect on the Health Care Crisis.

The passage of both the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”) and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (“FFCRA”) has provided economic stimulus and safety protocols to expand health care access. These measures have covered COVID-19 diagnostic testing, mandating the elimination of cost-sharing, such as co-payments, deductibles, and coinsurance, for a wide array of group health plans and insurances. While this improves accessibility to preventative measures, it leaves open a large regulatory gap for the actual treatment of COVID-19, where individuals are still vulnerable to out-of-pocket expenses until they reach their cap for insurance to kick in, “ exceeding “$8,000 for an individual and $16,000 for a family.” The benefit of expanding access to testing is immeasurable, but the high costs of treatment poses a significant risk to those who are already underinsured. Further, these acts fail to eliminate cost-sharing for the uninsured, which accounts for 27.9 million nonelderly individuals in the US in 2018. While the number of uninsured Americans is certainly alarming, it is a great improvement from the number of uninsured prior to the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), where over 46.5 million nonelderly individuals were uninsured in 2010. Yet, the many positive effects that have followed the enactment of the ACA are at risk of being undone, with the Supreme Court of the United States reviewing four legal questions pertaining to the ACA.

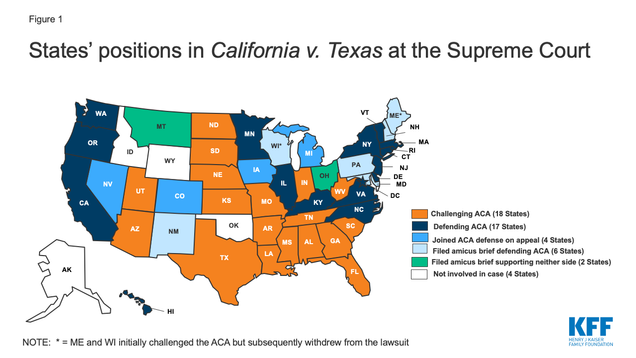

The Uncertainty of Health Care in the face of California v. Texas.

California v. Texas will be a test to the legislative muster of the ACA. With the recent confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, concerns of the ACA being overruled have surfaced as Justice Barrett has claimed that Chief Justice Roberts has “pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute.” The fate of the ACA hinders on whether the individual mandate is unconstitutional, and if so, if the individual mandate of the ACA is severable from the rest of the legislation. If the court does decide to overrule the ACA in its entirety, we may see more than 20 million individuals lose health care insurance, exacerbating the already grim public health crisis brought on by COVID-19, impacting our most vulnerable communities who struggle to gain access to health care.

California v. Texas will be a test to the legislative muster of the ACA. With the recent confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, concerns of the ACA being overruled have surfaced as Justice Barrett has claimed that Chief Justice Roberts has “pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute.” The fate of the ACA hinders on whether the individual mandate is unconstitutional, and if so, if the individual mandate of the ACA is severable from the rest of the legislation. If the court does decide to overrule the ACA in its entirety, we may see more than 20 million individuals lose health care insurance, exacerbating the already grim public health crisis brought on by COVID-19, impacting our most vulnerable communities who struggle to gain access to health care.

Disparities on Minority Care and COVID-19 Infection.

Racial and ethnic minority groups face the greatest barriers to health care access, and, in turn are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts. While the ACA had greatly reduced the proportion of racial and ethnic minorities who lack health insurance, there are numerous systemic and social hurdles that have left these minority groups uninsured at higher rates than white individuals. As a consequence, racial and minority groups have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, with racial minorities being over 2.6 times as likely to contract COVID-19, with rate of hospitalization for African American individuals being 4.7 times more than that of white individuals. Not only this, but the mortality rate is 2.1 times that of white people in the US, showing clear disparity in treatment outcomes and access to treatment.