Category: State Legislation

Raise the Age: An Evidence-Based Approach to Juvenile Justice Reform

For a large portion of America’s youth, the 1990s marked the end of juvenile justice. Blinded by fear and captivated by rumors of a “superpredator” uprising, legislatures across the country decided to “Get Tough” on crime. This meant decreasing rehabilitation efforts, increasing punitive repercussions and transferring increasing numbers of youth to adult criminal courts and adult correctional facilities. In effect, “Get Tough” legislation has lowered the legal age of criminal responsibility.

Just under 15,000 individuals under the age of 18 were held in adult jails and state prisons during the 1990s. As crime rates decreased and the “superpredator” hysteria waned, that number decreased sharply, but there are still upwards of 4,000 juveniles being held in adult jails and prisons as of 2018. As well, Emerging Adults, individuals 18–25 years of age, are held responsibility for a disproportionate amount of criminal activity in the United States. Making up only 10% of the total population, Emerging Adults account for almost 30% of criminal arrests and 21% of the adult prison population.

There is little dispute that America’s youth is being held legally responsible for a disturbing amount of crime. The question facing legislatures today is to what extent are these individuals actually culpable for their crimes and whether the adult justice system is the appropriate forum for addressing that culpability.

“Get Tough” Approach

The “Get Tough” movement was largely founded on the premise of the now debunked theory of the “superpredator” promulgated by social and political scientists in the early 1990s. In 1996, Princeton Professor and Criminologist John J. DiIulio Jr. co-authored a book on “the war on crime and drugs”, writing:

[A] new generation of street criminals is upon us — the youngest, biggest and baddest generation any society has ever known.

America is now home to thickening ranks of juvenile ‘superpredators’ — radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters, including ever more preteenage boys, who murder, assault, rape, rob, burglarize, deal deadly drugs, join gun-toting gangs and create serious communal disorders.’

Given that “[the] superpredator is a young juvenile criminal who is so impulsive, so remorseless, that he can kill, rape, maim, without giving it a second thought,” the logical solution to the impending “hordes of depraved teenagers” was imprisonment. Juveniles without a conscience were considered incapable of rehabilitation, and lawmakers were pushed to focus on the punishment and prevention of youth crime.

Scientific & Constitutional Review of “Get Tough”

Support for increased and prolonged incarceration relies heavily on the theory that severe punishment will deter crime. The threat of incarceration is thought to deter the general public from acting reckless or dangerous, while punishment “chastens” the individual to deter future criminal behavior. But both general deterrence and the “chastening effect” fall short of achieving their goals.

General Deterrence

In 2005, the Supreme Court began crediting scientific advances in adolescent neuro-psychology and proscribed the use of capital punishment and mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles. In Roper v. Simmons, Justice Kennedy opined:

[A] lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility are found in youth more often than in adults and are more understandable among the young. These qualities often result in impetuous and ill-considered actions and decision

Once the diminished culpability of juveniles is recognized, it is evident that the penological justifications for the death penalty apply to them with lesser force than to adults. We have held there are two distinct social purposes served by the death penalty: “ ‘retribution and deterrence of capital crimes by prospective offenders.’ ” Atkins, 536 U. S., at 319 (quoting Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U. S. 153, 183 (1976)

[T]he absence of evidence of deterrent effect is of special concern because the same characteristics that render juveniles less culpable than adults suggest as well that juveniles will be less susceptible to deterrence. In particular, as the plurality observed in Thompson, “[t]he likelihood that the teenage offender has made the kind of cost-benefit analysis that attaches any weight to the possibility of execution is so remote as to be virtually nonexistent.” 487 U. S., at 837.

For general deterrence to be effective, a juvenile must be capable of rationally assessing their actions before they act. As Justice Kennedy noted when he declared juveniles ineligible for the death penalty, juveniles act impulsively and irrationally. Therefore, the threat of prosecution in criminal court is unlikely to deter juveniles from criminal action.

The Chastening Effect

The chastening effect follows the age-old notion that punishment teaches a lesson. The idea that delinquent youth must be taught a lesson was abundant during the “superpredator” scare of the 1990s. The problem is, the evidence does not support that theory. In fact, the evidence suggests the contrary. Youth in the adult criminal justice system are more likely to re-offend upon release.

A Juvenile Recidivism Study in Vermont that compared 16 and 17 year old offenders charged with similar offenses in the juvenile and adult courts. The study found “[t]he three-year recidivism rate for juveniles adjudicated in the Family Division was 25%, compared to a 47% three-year recidivism rate for juveniles convicted in the Criminal Division.” Recidivism can often be attributed to higher levels of isolation and victimization experienced by you in adult correctional facilities, as well as the criminal culture perpetuated by other inmates.

Furthermore, recent studies have found that “the criminal justice system — and the accompanying violence, stress and isolation [ ] that come with being incarcerated — can interfere with brain development in adolescents and children.” A Harvard study on emerging adults concluded:

Higher recidivism rates among emerging adults are not surprising. Justice-involved emerging adults have been victims of violent crime and have experienced emotional and physical trauma at a higher rate than any other population. Exposure to toxic environments such as adult jails and prisons further traumatizes justice involved emerging adults, making them more vulnerable to negative influence, and as a result, increases recidivism among this group. Tailoring the justice system’s response to emerging adults’ developmental needs can reverse this cycle of crime and improve public safety.

“Diminished Culpability”

The Supreme Court has established precedent for amending existing law to meet the “evolving standards of decency,” and decency requires legislatures to re-evaluate the age of criminal responsibility.

The Brain

Much of the research cited by the Supreme Court back in the early 2000s found that those traits the Court ruled “diminished culpability” are present even in late adolescence (age 17, 18, and 19). However, as of January 11, 2019, 17 states still prosecute adolescence age 17, 18, and 19 as adults. An additional 5 states allow the prosecution of juveniles as young as 16 in adult court.

Recent advances in developmental brain science has shown that the human brain is still developing well in to their 20s. The well established consensus in the scientific community is that the brain functioning of a juvenile is not comparable to that of an adults until at least age 25. Particularly relevant to diminished culpability is the continuing development of the prefrontal lobe. The prefrontal lobe is responsible for executive functions such as risk assessment, planning, self-evaluation, goal-setting, and the regulation of our emotions.

Emerging Adults

Psychologist Jeffrey Arnett coined the term “Emerging Adult” in 2000. In the context of criminal justice, emerging adults refers to individuals having attained 18 years of age up to 25 years of age. This age group should be especially important to legislatures because emerging adults have higher rates of incarceration and recidivism. A national study of 30 states revealed that approximately 78% percent of emerging adults released in 2005 were re-arrested within 3 years. Whereas approximately 73% percent of those 25 to 29 and 63% percent of those 40 and older were rearrested within 3 years of release. The study found the pattern held true 5 years after release, and under 30% of those new arrests were violent.

Higher recidivism rates among emerging adults can be attributed Justice-involved emerging adults have been victims of violent crime and have experienced emotional and physical trauma at a higher rate than any other population. Exposure to toxic environments such as adult jails and prisons further traumatizes justiceinvolved emerging adults, making them more vulnerable to negative influence, and as a result, increases recidivism among this group. Tailoring the justice system’s response to emerging adults’ developmental needs can reverse this cycle of crime and improve public safety. Conversely, when emerging adults are provided with age-appropriate programing, the recidivism rate drops dramatically.

Moreover, a large portion of offenders, even violent offenders, age-out of crime. On average, property crimes peak at age 16 and violent crimes at age 17. According to a Justice Policy Institute report,

The evidence is clear that most young people will desist from criminal behavior without intensive justice-system involvement. By better addressing the unique needs and behavior of young adults, justice systems can develop responses that limit the risk youth pose to themselves and others during this transitory life stage.

Raise the Age

The “Raise the Age” campaign advocates for legislation that raises the maximum age of juvenile jurisdiction. Raising that age allows more developmentally underdeveloped individuals to be tried in a juvenile or family court. These courts are considerably more focused on education and rehabilitation that adult criminal courts.

In 2013, Massachusetts raised the age from 17 to 18, and juvenile crime has declined by 34%. Also on the decline in Massachusetts is the number of youth in juvenile facilities. Massachusetts success in raising the age can be attributed to “improving community-based responses and using cost-effective and developmentally appropriate approaches.”

Most states now include 17-year-olds in juvenile jurisdiction, but only one state – Vermont – has raised the age above 18 in conformance with advances in developmental studies of the brain.

Modern science tells us that emerging adults take more risks, have less self-control and are less culpable of their crimes. An evidence-based approach to legislation would demand a re-evaluation of emerging adults in the criminal justice system and the enactment of age-appropriate reforms.

Melissa Mayfield anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Melissa Mayfield anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Sanctuaries With Guns? Turning The Rule Of Law Upside Down; by Delegate David Toscano (D-Charlottesville)

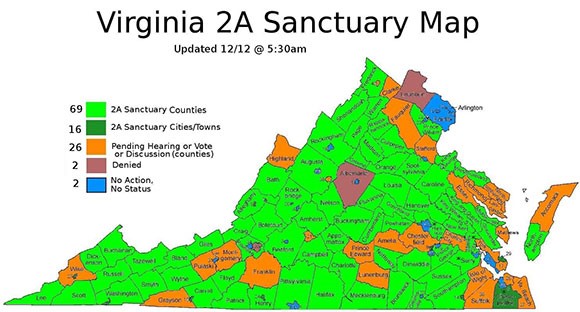

The Tazewell County, Virginia, Board of Supervisors recently jumped aboard the fast-moving “Second Amendment sanctuaries” train. In doing so, they embraced positions fundamentally at odds with state and federal constitutional law. Passing resolutions opposing certain laws or protesting governmental action is perfectly consistent with our traditions as a democracy, and no one should oppose the rights of citizens and their representatives to speak their minds. But Tazewell, and a number of other localities across Virginia, want to do much more. As Eric Young, an attorney and the county’s Administrator, put it, “our position is that Article I, Section 13, of the Constitution of Virginia reserves the right to ‘order’ militia to the localities; counties, not the state, determine what types of arms may be carried in their territory and by whom. So, we are ‘ordering’ the militia by making sure everyone can own a weapon." Other counties are announcing different schemes if gun safety laws are enacted: for example, the Culpeper County sheriff pledged to deputize “thousands of citizens” so they can own firearms.

Conservatives have railed for years against so-called “sanctuary jurisdictions,” criticizing localities that refuse to cooperate with federal immigration policies they deem heartless and ineffective. In the past year, however, some conservative lawmakers have taken a page from the progressive playbook, employing sanctuary imagery in opposition to gun safety legislation they deem to be an unconstitutional restriction of their rights under the Second Amendment.

The two approaches are classic cases of false equivalency. Jurisdictions that proclaim themselves sanctuaries for immigrants do not seek to violate the law; they simply refuse to engage local law enforcement in supporting actions that are federal responsibilities. They do not block the law, but simply insist that it should be enforced by those who have the responsibility to do so. For some proponents of so-called gun sanctuaries, however, the goal is to prevent enforcement of state law that the jurisdiction (not a court) deems unconstitutional.

After Democrats won majorities in both chambers of the Virginia General Assembly, fears of stricter gun regulations have inspired a rise in Second Amendment sanctuary activity in Virginia. Sanctuary efforts are driven mainly by the Virginia Citizens Defense League, a gun rights group to the right of the NRA. My office’s analysis of recent news accounts indicates that before November 5, just one county had passed a resolution; since the election, at least 80 localities (counties, cities, or towns) have passed some form of sanctuary resolution, and as many as 34 more are considering their adoption.

A REBELLION EMERGES

Second Amendment sanctuaries exploded onto the national scene in early 2019 after newly-elected Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker pledged to pass gun safety measures in Illinois. Within months, 64 of the state’s 102 counties passed sanctuary resolutions. After New Mexico expanded background checks in 2019, 30 of 33 counties declared themselves Second Amendment sanctuaries. Similar actions have either been taken or are under consideration in Colorado, Oregon, Washington state, and now Virginia.

In some cases, these resolutions simply register an objection to any infringement on gun owners’ rights. But some Virginia localities have gone further, indicating that they will not enforce state law that they deem unconstitutional. Some proponents have even resurrected words like “nullification” and “interposition,” terms first used extensively by Southern secessionists prior to the Civil War, and more recently during the “massive resistance” to federal laws requiring desegregation in the 1960s. They argue that constitutional officers in Virginia, such as Commonwealth’s Attorneys and Sheriffs, have discretion not to enforce laws that they consider “unconstitutional.” In Virginia, there has always existed some debate about the independence of these officers, but, while they are creations of the Constitution, their duties are nonetheless "prescribed by general law or special act.” In short, sheriffs may be “constitutional officers,” but they are not “constitutional interpreters.”

FLASHPOINTS IN THE CULTURE WARS

The emergence of these sanctuaries demonstrates a growing rift in our nation. For residents in many rural areas of our country, guns are viewed as part of their way of life, one some fear that they will lose due to national and state changes. Most gun owners are law-abiding citizens, and any effort to limit anyone's access to firearms is perceived as a direct attack on many things that they hold dear. During the Obama years, the manufacture and purchase of firearms increased in dramatic numbers in part due to unfounded fears that the government would try to take away guns. Voting to declare themselves “sanctuaries” is a way they can reassert some control over events that they feel are putting them at risk. For these communities, it matters little that reasonable gun safety proposals have largely passed constitutional muster, or that most proponents of these measures have no intention of taking anyone’s guns away unless it can be shown, in a court of law, that they are a danger to themselves or others.

At the same time, the general public is increasingly supportive of certain gun safety measures. An April 2018 poll found that 85 percent of registered voters support laws that would "allow the police to take guns away from people who have been found by a judge to be a danger to themselves or others" (71 percent "strongly supported"). These measures, called Emergency Risk Protection Orders (ERPO), or “red flag” laws, create judicial procedures by which persons with serious mental health challenges deemed a threat to themselves or others can have their weapons removed until their situation is resolved; courts can be engaged to protect the rights of the accused. And a March 2019 Quinnipiac poll reported that 93 percent of American voters support a bill that would require “background checks for all gun buyers.”

The energy behind support of gun measures like "red flag" laws is generated by concern for mass shootings, which are statistically rare but dramatic in their public impact, and the increasing numbers of gun-related suicides, which impact families and communities in quiet but devastating ways. On the latter front, there is a certain irony that some communities which have embraced Second Amendment sanctuary status also have higher gun suicide rates than other communities in their state. In Colorado, for example, nine of the 10 counties with the highest suicide rate over the past 10 years have declared themselves “Second Amendment sanctuaries,” many after the state passed an ERPO law in 2019. Of the 24 Colorado sanctuary counties for which suicide data is available, 22 (or 92 percent) had firearm suicide rates above the state average. Similarly, in Virginia, 36 of the 51 localities that have adopted a resolution to date and for which firearm suicide data is available have rates higher than the state median.

Recent polling in Virginia tells us that citizens of the Commonwealth are in step with the national trends documented above: Roanoke College’s Institute for Public Opinion Research recently released polling results which show that 84 percent of respondents favor universal background checks, and 74 percent support allowing a family member to seek an ERPO from a court. Yet in the very same pool of respondents, 47 percent believe it is more important to protect the right to own guns than to control gun ownership. The only way to make the math add up is to recognize that some people who strongly support Second Amendment rights may also support at least some reasonable gun safety measures—an approach the “sanctuary” advocates would never adopt. But even former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia might have had problems with some of the arguments being advanced by proponents of sanctuaries. “Like most rights,” he wrote in District of Columbia et. al. v. Heller, “the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. From Blackstone through the 19th-century cases, commentators and courts routinely explained that the right was not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose." In short, rights under the Second Amendment have never been absolute. And under both the national and state Constitutions, our courts are tasked with determining the constitutionality of laws—not local sheriffs.

HOME RULE VS. DILLON RULE

Proponents of Second Amendment sanctuaries have another problem in Virginia; the Commonwealth is what we call a “Dillon Rule” state. This means that if a power is not specifically permitted to a locality, state law rules. Progressives have been especially critical of Dillon Rule arguments in years past, believing that they have prevented localities from enacting policies—from local minimum wage ordinances to gun prohibitions—that seek to go further from state law. They have rarely been concerned that more conservative localities, if granted greater “home rule,” might enact policies, such as environmental regulations or building codes, that are more lax than state law. The Second Amendment sanctuary rebellion may prompt some to reexamine their views about how much additional power should be granted to localities.

The Virginia state legislature will soon consider several major gun safety measures, and opponents will likely strongly resist; as one county supervisor has said, “[W]e need to show them a crowd like they have never seen. They need to be afraid and they should be afraid.” Legislators should always be attuned to any unintended consequences of the laws that they pass; that is one reason why we have a deliberative process before bills are passed. But to leave the determination of whether to enforce duly-passed laws totally in the hands of sheriffs and local officials with discretionary power to determine their constitutionality is to turn the rule of law upside down, and is a direct attack on republican government and the Constitution itself.

David Toscano has represented the 57th district in the Virginia House of Delegates since 2006, and from 20011-2019 Del. Toscano served as the House's Democratic Leader. His forthcoming book is titled, In the Room at the Time: Politics, Personalities, and Policies in Virginia and the Nation.

A modified version of this opinion piece appeared on Slate.com.

Blanket Primaries or Ranked-Choice? Why Not Both?

A substantial number of Americans continue to voice dissatisfaction with current American electoral practices. This has put Justice Brandeis’s laboratories of democracy to work by prompting some states to exercise their powers to design election systems to experiment with various electoral reforms. Those powers derive from the state constitutions for elections of state officers; Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution to “[prescribe] the Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives”, and the U.S. Constitution Article II, Section 1 to determine how electors for President may be chosen.

Many states have allowed their municipalities to experiment, with a few states adopting reforms on a state-wide level. In the latter category, some states, like California and Washington, have adopted what is sometimes described as the top-two, blanket, or Louisiana primary, while Maine has implemented ranked-choice voting. While these reforms have been innovative, study of their effects reveals limited success in achieving advocates’ promises. This post concludes that by combining both reforms, states will be better positioned to access the positive outcomes hoped for.

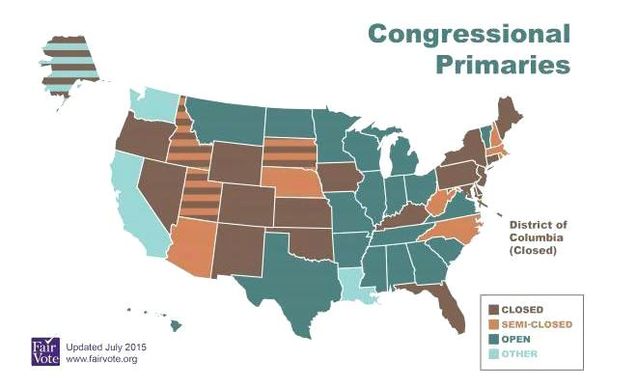

Blanket Primaries

Former Republican congressman from Oklahoma, Mickey Edwards, has argued that the problem with American politics is our  broken election system that rewards partisanship at the expense of good policy. Edwards argues that the culprit is the primary. Primary election turnout is notoriously low, with a recent Pew Research Center study celebrating a surge in participation in the 2018 House primary elections of 56% - a surge that still left turnout in that primary under 20%. The belief is that since political participation in primaries is so low, they are dominated by the most active, and most partisan, members of the parties, limiting the success of more centrist candidates, who are presumably more representative of their districts. In particularly politically active years, incumbents are at risk of being “primaried” by extremists in their party. Thus, the candidates in the general election tend to be more extreme, on both ends, than the district, and the eventual winner is then likely to represent only one extreme, rather than the district as a whole.

broken election system that rewards partisanship at the expense of good policy. Edwards argues that the culprit is the primary. Primary election turnout is notoriously low, with a recent Pew Research Center study celebrating a surge in participation in the 2018 House primary elections of 56% - a surge that still left turnout in that primary under 20%. The belief is that since political participation in primaries is so low, they are dominated by the most active, and most partisan, members of the parties, limiting the success of more centrist candidates, who are presumably more representative of their districts. In particularly politically active years, incumbents are at risk of being “primaried” by extremists in their party. Thus, the candidates in the general election tend to be more extreme, on both ends, than the district, and the eventual winner is then likely to represent only one extreme, rather than the district as a whole.

To address this concern, Edwards advocates for a reform known as “blanket” primaries, sometimes referred to as “Louisiana,” “jungle,” or, most accurately, “top two” primaries. This reform provides that in the primary election, there is a single ballot, with all candidates on the ballot regardless of party. The top-two candidates who receive the most votes then move on to the general election. This means that the candidates in the general election may both be from the same party, particularly in districts whose residents heavily identify with one party over the other. This may make for more competitive general elections, in that a candidate who is almost certain not to win isn’t on the ballot, in favor of a candidate who actually has a chance of convincing voters to vote for them. Also, along with Edwards’s hope that this will reduce partisanship by ensuring the candidates in the general election better represent the center of the district, advocates have also claimed that it will increase turnout.

Unfortunately, the data provides only marginal support for the proposition that blanket primaries reduce partisanship and increase turnout. An added challenge to blanket primaries is that because only the top-two move on, it is subject to vote splitting – if too many candidates from a party enter the race, they may end up without any candidates in the general simply by virtue of the number of candidates in the race, rather than voter preferences. Thus, blanket primaries are not a panacea, at least on their own, for electing more representative representatives.

Ranked-Choice Voting

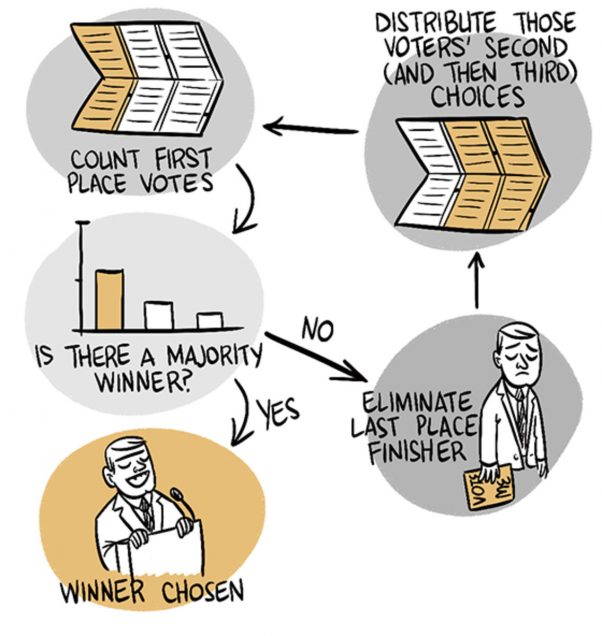

Maine has moved in a different direction, adopting ranked-choice voting (“RCV”), a darling of electoral reform advocates for decades. RCV has a long pedigree, first having been promoted publicly in the United States by William Robert Ware in the 1870s. Some states and municipalities flirted with a version of RCV, known as single transferable vote, in the last great shift in party power during the early- to mid-twentieth century. RCV and similar systems have also been successfully used internationally – including in Australia, and Ireland.

While there are many different iterations of ranked-choice voting, Maine has adopted the most typical approach. There, voters may rank candidates first, second, third, and so on. If a candidate gets a majority of first-rank votes, they are declared the winner. However, if no candidate receives a majority of votes, then the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated, and the voters who ranked that candidate first have their votes redistributed to their second-rank candidates. If no candidate has a majority, the new candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated, and their voters’ ballots are also redistributed. The system continues until a candidate has secured a majority of preferences.

Advocates of ranked-choice have also claimed that the system reduces partisanship, since candidates are encouraged to appeal to voters to rank them second, even if they can’t secure their first preference. Advocates also argue that it increases turnout by

making the ballot more reflective of voters’ wishes. As with blanket primaries, however, there is only modest statistical data showing that the turnout hopes are borne out.

A Proposal

States should consider merging the two systems, blanket primaries and RCV, in order to best access the benefits of each. The real problem that neither system effectively can address is the issue of turnout. Primary elections typically draw the most politically aware sector of the electorate that is most invested in who the candidates in the general election are, but turnout remains exceedingly low regardless of the system. Blanket primaries attempt to appeal to an electorate disenchanted by the current partisan model and looking to elect “the best candidate,” but since they continue to rely on a two-stage electoral model, they don’t resolve the fundamental problem. The most partisan members of the electorate participate in the blanket primary, and turnout surges, as it always does, in the general, after the partisans have already selected who will be on the ticket. Combining ranked-choice with the blanket primary would allow there to be a single election, ensuring the highest number of voters considering all the available candidates, not just those the partisans have already selected. Moving to a single election, with candidates on a single ballot regardless of party, and using RCV would ensure that the larger electorate would be able to weigh-in, allow them to rank their preferences, and ensure that the candidate who emerged was the preferred candidate of a majority of voters. This will increase elected officials’ mandate, and provide more information about what direction the district would like to go in.

Slowing Chipping Away at Child Marriage in the US

Child marriage is condemned by the international community and the stated goals of the U.S. State Department. In fact, the State Department’s “U.S Global Strategy to Empower Adolescent Girls” calls marriage before 18 a “human rights abuse.” However, most states still have laws that allow for the marriage of children under the age of 18. Eighteen states don’t even have a minimum age that a child can be married. So far in the US, only two states, New Jersey and Delaware, have banned all child marriages with no exceptions. Between 2016 and 2018, eleven states have passed laws that limit child marriage but still keep some exceptions, mainly relating to parental consent and 16 or 17-year-olds marrying someone within a few years of their own age. Ten additional states have introduced bills curtailing child marriage, many of which were sent to study or died at the end of the legislative session in 2018, but with plans to be reintroduced in the next session.

The advocacy organizations leading the charge for new protections for minors are insistent that only a limit of 18 years old with no exceptions is good enough; especially since some of the legal exceptions exacerbate the problem. For example, requiring only parental consent, especially when only a single parent’s consent is needed for marriage under the age of 18 leaves minors unprotected from marriage due to coercion. A few states still allow for exceptions when the girl is pregnant, even if she is below the age of consent. Pregnancy, of course, is one of the situations where girls are most often coerced into marrying men, some of whom are their rapists.

Earlier this month, Ohio joined the ranks of states attempting to fix this problem, if imperfectly. House Bill 511 was introduced by

Republican Rep. Laura Lanese and Democratic Rep. John Rogers last year with the intention of updating the former law, which treated boys and girls differently. Previously, girls could get married at 16 with parental consent, although boys could not get married below the age of 18 without the consent of a juvenile court.

The new law, which was signed by Governor John Kasich just before he left office in January, creates gender equality by requiring both boys and girls to be 18 in order to get married. The only exemption allowed is a marriage at 17 if there is no more than a four-year age difference, if a juvenile court consents and requires a 14 day waiting period. In the processes of determining whether to give consent, the court is instructed to consult with the parent or guardian, and appoint a guardian ad litem. Additionally, a court must determine if the minor is in the armed forces, employed and self-subsisting or otherwise independent of a parent or guardian, and if the minor is free from force or coercion in the decision to marry. The couple must also have completed marriage counseling satisfactory to the court. Additionally, a provision was added that requires official proof of age.

There were strong reasons for the Ohio Legislature to act. According to the Dayton Daily News, over 4,400 girls aged 17 or younger were married in Ohio between 2000 and 2015. Of those, 59 were 15 or younger, and three were 14 years old. Additionally, according to the Ohio Department of Health, there were 302 boys under the age of 17 were married between 2000 and 2015, with the approval of parents or a juvenile court. A significant driver of the child marriages seems to be when a minor girl gets pregnant by an older man.

There were strong reasons for the Ohio Legislature to act. According to the Dayton Daily News, over 4,400 girls aged 17 or younger were married in Ohio between 2000 and 2015. Of those, 59 were 15 or younger, and three were 14 years old. Additionally, according to the Ohio Department of Health, there were 302 boys under the age of 17 were married between 2000 and 2015, with the approval of parents or a juvenile court. A significant driver of the child marriages seems to be when a minor girl gets pregnant by an older man.

These types of marriages have harsh consequences including being 50% more likely to drop out of high school, three times more likely to experience psychiatric disorders, and divorce rates of almost 80%, which can more than double the chance a teen mother ends up in poverty. Additionally, women who marry as minors lack the ability and resources to remove themselves from a harmful relationship. For example, most domestic-violence shelters cannot accept minors, minors who leave home are considered runaways, and child-protective services can usually do little in regards to legal marriages. Furthermore, a child is unlikely to have the resources to escape an abusive relationship, pay attorney fees, or even sign any other legally binding document.

In Massachusetts, there is currently no age requirement for marriage, with minors requiring a half page petition, and approval by parents and the courts. The statistics for child marriages in Massachusetts consist of 1,200 children as young as 14 married from 2000 to 2016. In the time period from 2005 to 2016, 89% were underage females married to adult men. In 2018, Democratic Sen. Harriet Chandler and Democratic Rep. Kay Khan introduced bills (S785/H2310) to end all child marriage with no exceptions. The bill stalled, however, because as Democratic Rep. Khan noted because legislators were not been able to hear from victims who want to talk about their experience. The bill was refiled at the beginning of the new legislative session that began in January.

Slowly, but surely, states are addressing the evils that come with child marriage.

Amanda Simile will graduate from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Amanda Simile will graduate from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Stop the Clock: Implications of Switching Time Zones

The holiday season is joyous for many reasons; from family, friends, and food, there is ample joy and merriment to go around. There is one aspect of the season that doesn’t match these factors; especially in New England – darkness. At the outset of winter, on December 21st each year, the sun sets in Boston at 4:11pm. There are many negative effects of darkness setting in before the end of the workday – with increased crime, traffic accidents, and seasonal depression being one of the most paramount. Boston’s sunset is not the earliest in the area, with municipalities in Maine experiencing sunsets earlier than 4pm; but it is the earliest of the major cities, beating out Buffalo, NY despite being further south.

Early sunsets do not become apparent in New England until clocks fall back in line with the change from Daylight Savings Time. Daylight Savings is a federal program instituted during World War II that the country has become accustomed to; the federal legislation only permits states to opt out of the program, but it does not allow states to make the program permanent, which would keep the clocks from falling back an hour. Hawaii and Arizona have opted out of the program – made available through the US Energy Policy Act of 2005, allowing any state that lies entirely within one time zone to opt out.

New England states, primarily Massachusetts and Maine at this point, have been considering a change to the Atlantic Time Zone

in order to increase the number of waking hours with sunlight. With a change to Atlantic Time, and subsequent opting out daylight savings, New England would be out of sync with the rest of the Eastern Time Zone from November to March, or the period in which clocks “fall back” in line with daylight savings in the Eastern Time Zone. A transfer to Atlantic Standard Time – which includes Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and eastern Canada – would mean jumping an hour ahead of the Eastern time zone from November to February. The time zones would align from March to October.

While the benefits of having an extended amount of light in the evening hours are readily apparent, there are several drawbacks that accompany a change. Early risers in particular, who are likely accustomed to the sun being out while they start their days have reason to complain. School aged children may be leaving to their schools in darkness in the morning, and businesses that transact on financial markets may be put out of sync with the markets they depend on.

If New England were to change to Atlantic time, there would be a two-step process. First, the interested states would have to decide to leave. Second, the states would have to consult the US Department of Transportation, the cabinet agency that regulates time zones. States, municipalities, business interests, and others would have the opportunity to weigh in during both steps.

There could be major issues with “commerce, trade, interstate transportation and broadcasting” if one state moves ahead one hour while its neighboring states remain in the Eastern Time Zone. It seems to be a requirement of widespread support and agreement for any change in this area to take effect. Lawmakers in Maine might support the change – in May 2017, Maine’s Senate passed a bill that would move the state to the Atlantic Time Zone — if approved by residents in a state-wide referendum. Maine conditioned the change, subject to their approval, on Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

There could be major issues with “commerce, trade, interstate transportation and broadcasting” if one state moves ahead one hour while its neighboring states remain in the Eastern Time Zone. It seems to be a requirement of widespread support and agreement for any change in this area to take effect. Lawmakers in Maine might support the change – in May 2017, Maine’s Senate passed a bill that would move the state to the Atlantic Time Zone — if approved by residents in a state-wide referendum. Maine conditioned the change, subject to their approval, on Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Some states seem to have considered the idea and decided against it, with the New Hampshire Senate voting against a bill that would move the state to the Atlantic Time Zone by a 16 to 7 vote; at the same time, the bill passed the house with a voice vote. While there has yet to be an affirmative move, the proponents of the change are enlivened by the action around the issue and are hopeful for the future.

Massachusetts established a commission to study the issue. In a neutral report neither supporting or disavowing the change, the commission stated its findings that "People tend to shop, dine out, and engage in other commercial activities more in after-work daylight,". . . "Year-round DST could also increase the state's (competitiveness) in attracting and retaining a talented workforce by mitigating the negative effects of Massachusetts' dark winters and improving quality-of-life." More daylight could also reduce street crime, on-the-job injuries and traffic fatalities, and boost overall public health, the commission found.

States in the Northeast seem intrigued by the change, but alterations of the particulars of their citizen’s days are deeply personal to their citizens may be a drastic change to take without widespread public support. In Arizona, the effects of their non-adherence to daylights savings time are apparent when the state is out of sync with the rest of the surrounding states – constant clarification of what time is in effect, setting different meeting times, etc. Results on an individual basis are a mixed bag, with businesses that are purely local and that thrive in the daylight being supporters of the longer day due to increased business, and those who constantly run up against timing differences by virtue of dealing with other regions.

It will be interesting to observe if public support for a time zone change increases as people in New England become aware that doing so is a possibility to increase their daylight hours in the depths of winter. In any case, it is clear that the states’ legislatures have identified it as a possible issue.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

Drew Kohlmeier is a student in the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020 and is a native of Manhattan, KS, graduating with a degree in Biology from Kansas State University in 2016. Drew decided on Boston for law school due to his interest in health care and life sciences, and will be practicing in the emerging companies space focused on the life sciences industry following his graduation from BU.

The Future of Supervised Injection Sites in Massachusetts and Beyond

With Massachusetts and the country facing a rising opioid overdose epidemic, lawmakers are looking to some controversial measures to curb overdose deaths. One of those measures being considered is supervised injection sites, also called safe injection sites or safe consumption spaces. Safe consumption spaces, of which there are 100 worldwide, are clean spaces where people can legally use pre-obtained drugs with supervision from healthcare professionals who aim to make injections as safe as possible while providing health care, counseling, and referral services to addicts. While safe injection sites have been successfully implemented in Canada, Australia, and Europe over the past 30 years, attempts to create such sites in San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and more U.S. cities have not yet been successful. Beyond policy arguments as to whether these sites are effective, sites in the United States also face significant legal hurdles under federal law.

According to supporters of safe injection sites around the country and the world, the policy is an effective and relatively low-cost way to prevent overdose deaths and manage harm with no demonstrated consequences of increased drug use or increased crime. Opponents of safe injection sites, including Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, have pointed to increased opioid deaths in

recent years in Vancouver, which established its supervised consumption site Insite in 2003, to argue that safe injection sites are not actually effective in preventing overdose deaths. However, those arguments are misleading, as experts have stated that the increase in overdose deaths in Vancouver are due to the influx of fentanyl being added to drugs, and that Insite actually saw a 35% reduction in overdose deaths around the facility in the two years after it opened. While there are also studies questioning the efficacy of safe consumption sites—calling into question whether they have a significant impact on reducing deaths and reaching a significant amount of drug users—even the negative studies generally criticize safe consumption sites as being relatively ineffective as opposed to actively harmful. There are dozens of peer-reviewed scientific studies that have found that safe injection sites actually do significantly benefit those who are addicted to opioids and prevent opioid deaths. Notably, no death has ever been reported in an injection site, and a review of studies concluded that injection sites were associated with less outdoor drug use and did not appear to have any negative impacts on crime or drug use.

Despite the strong evidence backing the societal benefits of implementing and supporting safe injection sites, the policy faces significant legal and political obstacles in the United States. Perhaps the biggest hurdle that advocates of safe injection sites face is the potential legal liability of such sites under federal law and opposition from the Justice Department. The Controlled Substances Act makes it illegal to “knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place, whether permanently or temporarily, for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance,” as well as to knowingly manage such a place. The plain language of that law may render implementation of safe injection sites impossible without some change or exception carved out in federal law.

However, advocates of safe injection sites do have a glimmer of hope that, once the first U.S. site is created, it will pass judicial muster through a creative legal argument proposed by law professor and drug policy expert Alex Kreit. In his paper, Kriet argues that a provision in the Controlled Substances Act providing immunity to state and local officials who commit drug crimes while enforcing local laws could protect safe injection sites from a crackdown by the federal government. Kreit has stated that the infrequently cited rule has previously been used in situations where authorities have seized marijuana and then returned it in states where marijuana has been legalized. Under this theory, those involved in safe injection sites would be protected so long as they were acting in accordance with a city ordinance or state law supporting safe injection sites. Other experts have expressed skepticism that such an argument would pass muster, however, with some stating that Kreit’s argument is a “stretch,” and that any path toward legality for safe injection sites lies in convincing the federal government not to target safe injection sites on public health grounds.

However, advocates of safe injection sites do have a glimmer of hope that, once the first U.S. site is created, it will pass judicial muster through a creative legal argument proposed by law professor and drug policy expert Alex Kreit. In his paper, Kriet argues that a provision in the Controlled Substances Act providing immunity to state and local officials who commit drug crimes while enforcing local laws could protect safe injection sites from a crackdown by the federal government. Kreit has stated that the infrequently cited rule has previously been used in situations where authorities have seized marijuana and then returned it in states where marijuana has been legalized. Under this theory, those involved in safe injection sites would be protected so long as they were acting in accordance with a city ordinance or state law supporting safe injection sites. Other experts have expressed skepticism that such an argument would pass muster, however, with some stating that Kreit’s argument is a “stretch,” and that any path toward legality for safe injection sites lies in convincing the federal government not to target safe injection sites on public health grounds.

If cities and states cannot find a legal workaround protecting those involved with the safe injection sites, advocates likely face an uphill battle in convincing their communities and the Justice Department to accept injection sites. Attempts at establishing sites have not been politically palatable, as demonstrated by efforts in San Francisco and Boston. California Governor Jerry Brown vetoed a bill that would have allowed supervised drug consumption sites in the state and went so far as to describe it as “enabling illegal drug use.” In Massachusetts, in addition to Governor Baker’s opposition to the idea of safe injection sites, the Senate ultimately stripped a provision authorizing safe injection sites from its comprehensive opioid bill this past legislative session, instead replacing the pilot program with a commission to study the feasibility of establishing such sites. In addition to opposition from state Governors and a lack of strong state government support, it seems highly unlikely that the current federal administration would turn a blind eye to safe injection sites on public health grounds. In addition to a statement from the Vermont U.S. Attorney’s Office criticizing the policy and affirming that the United States Attorney would impose ramifications under federal law, there have been multiple other instances indicating the administration’s hostility towards safe injection sites and similar policies. In August, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein wrote an op-ed in the New York Times opposing safe injection sites and emphasizing the fact that they violate federal law. The Justice Department also “promise[d] [a] crackdown” on supervised injection facilities on an NPR radio show.

While there is scientific and global community support for safe injection sites, their future in the United States is still unclear, especially under the current federal administration. Until there are more assurances that sites could operate without intervention from federal law enforcement, it seems that most cities and states that have been at the forefront of the push for safe injection sites do not have the political will or capital to open the country’s first site and become the guinea pig of the movement. Philadelphia, however, may be the one city willing to go first. In August, Philadelphia Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley said that Rosenstein’s opposition and warnings from the Justice Department would not prevent Philadelphia officials from further exploring the idea. Currently, Philadelphia seems to be going forward with its plan to allow, but not publicly fund, a non-profit site called Safehouse, which could serve as a jumping off point for litigation determining the legality of the sites and potentially creating more certainty for other interested cities and states. As for Massachusetts, it seems unlikely that the Commonwealth will be establishing any safe injection sites in the near future, though the members of the commission created in last session’s opioid bill will no doubt keep a close eye on Philadelphia as its safe injection site plan comes to fruition.

Massachusetts Regulates Short-Term Rentals

Massachusetts’s Governor Baker signed An Act Regulating and Insuring Short-Term Rentals on December 28, 2018. The act regulates short-term rentals provided through services like Airbnb. The governor rejected an earlier version of the bill, and returned amendments primarily allowing for an exemption for owners who rent out their property for two weeks or less per year, and reducing the amount of information provided publicly about rentals owners. The bill was motivated by concerns that the rise in short-term rentals drives up housing costs and pushing out long-term residents. The statewide bill comes after both Boston and Cambridge individually passed laws essentially having the same effects. However, the Boston law was challenged by Airbnb, who filed suit in federal court claiming that the regulations are “Orwellian” and violate several laws, including laws that protect online companies from being held liable for the actions of their users. The city of Boston is currently holding off on some of the regulations passed pending the resolution of the court case. Airbnb had not yet said if it will challenge the new Massachusetts law.

The statewide law has two main components: first, that all short-term rentals are taxed by the Commonwealth, and can be additionally taxed by local governments, and second, that all owners of short-term rental properties must register with the state and hold insurance. The registration requirement was a cause of debate.  Lawmakers, including Governor Baker, were concerned about violating the privacy of owners by publishing their names and addresses publically. In the amendments to the July bill that Governor Baker rejected, the registration requirement was changed so that only the owner’s neighborhood and street name would be published, not their exact address. The law also dictates eligibility in order to register. To be eligible to be a short-term housing unit, the space must be compliant with housing code, be owner-occupied and be classified for residential use, among other requirements. Another cause of debate was an exemption for occasional renters. Governor Baker originally wanted owners who rent their properties for 150 days or less to be exempt from the regulations. However, in the final version of the bill, the exemption was decreased to 14 days.

Lawmakers, including Governor Baker, were concerned about violating the privacy of owners by publishing their names and addresses publically. In the amendments to the July bill that Governor Baker rejected, the registration requirement was changed so that only the owner’s neighborhood and street name would be published, not their exact address. The law also dictates eligibility in order to register. To be eligible to be a short-term housing unit, the space must be compliant with housing code, be owner-occupied and be classified for residential use, among other requirements. Another cause of debate was an exemption for occasional renters. Governor Baker originally wanted owners who rent their properties for 150 days or less to be exempt from the regulations. However, in the final version of the bill, the exemption was decreased to 14 days.

Not surprisingly, the hotel industry supports the bill. Paul Sacco, the President and CEO of Massachusetts Lodging Association, said:

“This is a tremendous victory for municipal leaders and the people of Massachusetts who have been waiting for years while Airbnb rentals have exploded, resulting in skyrocketing housing costs and disruptions in local neighborhoods. By adopting a more level playing field between short-term rentals and traditional lodgers, lawmakers made great strides toward a more fair and sensible system.”

Airbnb had a far less enthusiastic response however. In citing concerns about the property owners who use Airbnb to earn extra income, Airbnb said that they would “continue the fight to protect our community and the economic engine of short-term rentals for hosts, guests, and local small businesses”

While Massachusetts is the first state to pass a law, many other cities have passed similar laws in the recent years. In Nashville, the city passed a law in January which focused on taxing short-term rentals that are not owner-occupied in order to fund affordable housing development in the city. The “linkage fee” tax is controversial, with lawmakers questioning if the fees generated are enough to actually impact the lack of low-income housing within the city. Seattle passed a similar tax law in November 2017. The legislation aims to encourage owners who rent out a spare bedroom and discourage investors who buy entire buildings for use as short-term rentals. Finally, New York City passed regulations in July 2018 which requires Airbnb, and other similar companies, to provide information about the properties listed for rental within the city. However, Airbnb sued in federal court claiming that the requirement to provide information to the city violated the company’s fourth amendment right against search and seizure. The law was set to take effect in February 2019, however the Judge granted a preliminary injunction in favor of Airbnb saying, “The city has not cited any decision suggesting that the government appropriation of private business records on such a scale, unsupported by individualized suspicion or any tailored justification, qualifies as a reasonable search and seizure.”

Jessica A. Hartman is a member of the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020.

Jessica A. Hartman is a member of the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020.

Automatic Vote Registration is a Necessary Step in the Right Direction to Increase Voter Turnout

In 2016, Donald Trump won the electoral vote, and therefore the presidency, because of fewer than 80,000 people spread over 3 states; about the same population as Scranton, Pennsylvania. While there are many ways to analyze this narrow margin, the most important may be that elections can be decided by a small number of votes. This fact makes it increasingly important that governments ensure every eligible citizen has the ability to conveniently vote. When 80,000 people can decide a national election, any obstacle that inhibits citizens from voting can drastically change who our representatives are. One recent effort in several states is automatic voter registration. While not the solution to all voting problems, it is a worthwhile first step towards greater voter turnout.

In 2015, Oregon became the first state to adopt automatic voter registration.Since then, 12 more states and the District of Columbia have enacted similar legislation. Most recently, in August of 2018, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed an automatic registration bill into law. Automatic voter registration laws change the traditional opt-in registration methods into opt-out plans. The Massachusetts law, for instance, requires automatic registration for anyone who completes a transaction with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) or signs up for state healthcare (MassHealth), unless they opt-out of registration . The law will take full effect in January 2020, in time for the next presidential election.

Because automatic voter registration is a relatively new design model, the research into whether or not it actually increases voter turnout is limited. However, the initial research from the Center for American Politics (CAP) seems positive. According to early numbers, of the 272,000 people in Oregon who were registered through the automatic system, more than 1/3 of them (approximately 98,000 people)voted in the 2016 election . This same data also suggests that Oregon's automatic registration law has created a potential pool of voters who are more representative of the age, income, and ethnicity of the state’s residents. At the very least, there is clear and conclusive evidence to confirm that automatic voter registration will definitely increase the number of people who have the option of voting in the next election. Since 2016, Oregon’s registration rates have quadrupled at state DMV offices. There have been similar results in Vermont where, after only six months of its new system, registration rates rose 62% from the previous year . While the effect remains to be seen in Massachusetts, officials estimate that approximately 680,000 new voters will be registered because of the bill.

Despite these promising results, automatic voter registration has not been without its critics. Opponents are concerned about various issues such as fraud, duplicate registrations, and accidental enfranchisement for undocumented immigrants. Proponents believe that these concerns, however, are largely unfounded. To combat the risk of fraud and duplicate registrations, many states conduct their automatic registration through multiple governmental agencies that can all supply and confirm correct identifying information (such as changed addresses or last names). The Massachusetts law allows registration through two different agencies and also requires the state to link with the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC); a third-party nonprofit that will update and report changed voter information to the state. Concerns of accidental registration of undocumented immigrants are most heightened in places such as California, which allows undocumented residents to obtain drivers licenses while also providing automatic registration through the DMV. Election officials in California, however, state that all automatic registrations in California are cross referenced with voter eligibility databases the ensure that this fear cannot come to fruition.

Proponents of automatic voter registration argue that while the potential negative side effects of these laws are negligible, the benefits are huge. Automatic registration is a small, but highly effective, tool to help protect the most vulnerable from having their voting rights infringed upon. One important example of this can be found in the state of Georgia. Georgia has had automatic voter registration through the Department of Driver Services (DDS) since September of 2016. Prior to adopting automatic registration, the state required voter applications to meet extremely strict “precise match” requirements. Under these precise match requirements, applications ccould be held or rejected if they did not precisely match the information the state already had on file for that person. Applications were held up for trivial issues such as missing hyphens or a signature that looked slightly different. In 2016, The Secretary of state ended these precise match requirements just as the state began implementing automatic voter registration.

During the 2018 midterm election Secretary of State Brian Kemp reinstated the practice of requiring precise match’s for voter registration and absentee ballots. This requirement caused widespread rejection of absentee ballots and mailed in voter registration applications-- more than 53,000 ballots and applications because of precise match reasons. While 32% of residents in Georgia are black, approximately 70% of the rejected applications were from black residents. This seemingly suggests that one of the greatest issues with automatic voter registration is simply that it doesn’t do enough on its own to prevent voter suppression.

While automatic registration can effect great change in terms of the number of people who are registered to vote, it is only a beginning, and not an end, to improve the problem of voter suppression and voter turnout. The decision whether or not to vote is almost as personal as the decision of who to vote for. All citizens should have the right to choose whether they want to vote in any particular election. When state laws and policies make it difficult for people to register, the government ends up taking the decision out of the hands of too many Americans. The move towards easier registration is an important one. For a country whose elections are decided by so few votes, it’s imperative that anyone who wants to vote, gets to.

Ashley Zink anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law with a Juris Doctor in May 2020.

Ashley Zink anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law with a Juris Doctor in May 2020.

Can Single-Payer Really Happen?

Healthcare is on the frontlines of legislative debates— the U.S. has the most expensive care and reports the poorest outcomes of all rich democracies (RDs). Several states have proposed legislation to innovate healthcare access and to safeguard against the destruction of the ACA. One “old idea” that recently gained momentum is single-payer, and for New York (NY), it may become a reality, with its fate resting with the new legislature. To date, only one state has briefly “experimented” with single-payer – Vermont, and it failed due to gross underestimation of its costs. In NY, a landmark study that evaluates the viability of NY’s single-payer bill, known as the New York Health Act (NYHA), conducted by RAND, detailed benefits and setbacks of the proposed legislation, and public reaction was mixed. Despite the not so encouraging findings, lessons can still be learned from this report.

Single-payer, coined as “Medicare for all”, is a health insurance system in which a single public agency organizes healthcare financing, ideally covering all types of essential healthcare services. Delivery of care itself, however, would remain largely private in a single-payer system.

Proposals for single-payer in the U.S. are not new. The earliest version came in 1943 by Senators Robert Wagner (D-New York), James Murray (D-Montana), and Representative John Dingell, Sr. (D-Michigan), known as the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill (and subsequently endorsed by President Truman in 1945). The post-World War II bill proposed funding health care through payroll and income taxes. The bill became entangled with the Cold War , was vilified as “socialized medicine” by its opponents, and was discarded. The idea was revived in the 1950s, when it was nearly impossible for an aging population to get private health insurance. The elderly advocated for subsidized coverage since they are no longer able to afford their care, and hospitals advocated for it to ensure that the healthcare services they provide were paid for. The result: Medicare was enacted in 1965— the first form of single-payer insurance in the U.S.

Single-payer is gaining popularity once again. According to a Reuters poll, 70% of Americans support some form of single-payer coverage. Why? First, with the implementation of the ACA, there was a national momentum for states to expand their healthcare coverage. The health exchange created by the ACA made coverage accessible for many middle-income families and individuals. On the Medicaid side, progressive states elected to expand their eligibility coverage for individuals earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level in exchange for a 50% match in federal subsidies, a benefit many states enjoy. The most appealing provision of all is the mandated coverage of pre-existing conditions. With the all Republican take-over of the federal government in 2016, many Americans worried about what would happen to their coverage. Over the next two years, the ACA underwent congressional budget cuts, but despite efforts by Congress and President Trump, the ACA has grown in popularity with the general public.

Single-payer is gaining popularity once again. According to a Reuters poll, 70% of Americans support some form of single-payer coverage. Why? First, with the implementation of the ACA, there was a national momentum for states to expand their healthcare coverage. The health exchange created by the ACA made coverage accessible for many middle-income families and individuals. On the Medicaid side, progressive states elected to expand their eligibility coverage for individuals earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level in exchange for a 50% match in federal subsidies, a benefit many states enjoy. The most appealing provision of all is the mandated coverage of pre-existing conditions. With the all Republican take-over of the federal government in 2016, many Americans worried about what would happen to their coverage. Over the next two years, the ACA underwent congressional budget cuts, but despite efforts by Congress and President Trump, the ACA has grown in popularity with the general public.

In NY, the concept of single-payer was first introduced in 1992 by Assembly member Richard Gottfried (NY-D). The goal of NYHA is to provide universal insurance coverage with no cost-sharing for New Yorkers, regardless of legal status, and would cover almost all comprehensive services. Bill proponents expect increased access to care and reduced costs by removing high administrative overhead costs and reducing unjustifiably high prescription drug costs. Much like the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill, NYHA would be funded through payroll and income taxes. Since 2015, the NYHA has passed the Assembly floor four times. Although 31 state senators co-signed the bill, it has been stopped in the Senate by just one vote. This may now change with the Democrats taking back the Senate majority, although the cost may be a deterrent.

Despite the national and legislative enthusiasm, New Yorkers have been skeptical of single-payer reform. According to a 2018 Mercury Public Affairs poll, only 33% support the bill. Over 60%, however, said they would support increased subsidies to assist low and middle-income families. Why the opposition? The number one reason of 66% polled: taxes would pose a high burden.

The RAND study assessed “near-term” and “long-term” impacts of the bill. Overall, it found that single-payer would be viable, but with big caveats. The system would expand health care access, all while generating an estimated $15 billion in net savings (3.1%) on healthcare costs by 2031. Still, near-term are where the problems lie. From the political side, this would require the federal government to issue a waiver to redirect all federal and state funds to NYHA. Just weeks prior to this report, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services called California’s similar proposal “unworkable” and indicated similar waivers would not be approved. On the fiscal side, health care reform comes with a steep price: $139 billion in additional state tax revenue would be needed by 2022, that is 156% more than what is currently being collected. This amount would be amassed through payroll and income tax that would supplant the employer contribution and premiums and out-of-pocket costs. RAND applied a generic tax schedule based on three income brackets. For low-income families, they would be taxed 6.1% of their payroll income and 6.2% for non-payroll income by 2022. For middle-income families, the rates would range from 12.2% to 12.4%, and for high-income, their tax rate would increase up to 18.3% - nearly three times of what they are paying now. Moreover, Medicaid and Essential Plan (i.e. the NY Health Exchange) enrollees would pay more to get healthcare coverage. Assembly member Gottfried praised the study and suggested that they can adjust taxes accordingly so that high income families would pay more in taxes in order to help low and middle-income families afford their care. These tax hikes would exceed the combined costs of what New Yorkers are currently paying in taxes and healthcare benefits—explaining the bill’s unpopularity. Using the RAND report as a guide, it is likely that the state legislature will explore mechanisms to help finance their proposal in the upcoming session.

While single-payer hasn’t had much luck in the U.S., universal care payment methods, including single-payer, have been successful in other RDs. Regardless of each RD’s financing method, there is one consistent feature of success: national political will to implement it. Imagine if the politics of the cold war did not interfere with establishing a national health insurance plan? Would it have been possible to implement a streamlined and efficient plan? If our culture would have capitalized on the Medicare momentum, would we accept a collective sense of community regarding our healthcare? Vermont tried to implement single-payer with little success due to gross budget underestimations and faint national support. The RAND report sheds light on the cost of single-payer and suggests that there needs to be federal political will to support it. Let these findings and other evidence guide lawmakers as the search for a modest solution continues. Perhaps Wagner’s vision may still be a solution.

Sarah Zahakos is working toward a PhD in Health Law, Policy & Management at the Boston University School of Public Health.

AHRQ T32 Research FellowTraining in Health Services Research for Vulnerable PopulationsGrant # 2T32HS022242

Examining the ERA’s Comeback: the Legal Debate Over a 38th Ratification

At a time when the issues of gender and sexual harassment have come to a head, some activists are looking to a decades-old proposed constitutional amendment to secure gender equality. The Equal Rights Amendment (“ERA”), originally proposed by suffragist Alice Paul in 1923, would affirmatively state that no person’s rights under the law may be denied or abridged based on sex. This would raise the level of judicial scrutiny afforded to claims of gender discrimination from the “intermediate” and often uncertain level of scrutiny to the much more arduous level of strict scrutiny. Strict scrutiny would make gender a protected class and grant legal safeguards for gender discrimination claims on par with those of claims of racial discrimination. Despite renewed public support for the ERA, its complicated history and potential future passage raise contentious legal issues.

The ERA was introduced in every Congressional session from 1923 until its eventual passage in 1972. After passage, the landmark legislation went to the states for ratification; needing the ratification of at least 38 states—two thirds of the states—before the congressionally imposed deadline of March 22, 1979. While there was an initial surge in ratification, only 35 states ultimately ratified the ERA. Congress extended the deadline to June 30, 1982, however no other states ratified in that time.

After the deadline passed without the prerequisite ratification, the ERA largely disappeared from the national conversation and lay dormant until its contemporary resurgence. Millions participated in the Women’s Marches in response to President Trump’s election, and the #MeToo movement aimed at ending workplace sexual assault and harassment; both reflect a renewed push for gender equality. In light of those movements, the ERA, too, gained steam. On March 22, 2017, exactly 45 years after Congress first passed the ERA, Nevada became the 36th state to ratify the amendment. A little over a year later, on March 30, 2018, Illinois followed suit, leaving the ERA needing only one more state to reach the required two-thirds of states. The final necessary ratification may come in the upcoming legislative session beginning in January, as Virginia lawmakers have recently wrapped up VAratifyERA, a 10-day, bipartisan bus tour of Virginia aiming to gather support for the bill across the state.

While activists pursue a 38th ratification, legal scholars debate the legitimacy of a passage of the amendment so far beyond Congress’ deadline. Does Congress have the power to simply extend the deadline again and certify the ERA’s passage if a 38th state passes it, or did the ERA expire in 1982, rendering a 38th ratification moot?

While activists pursue a 38th ratification, legal scholars debate the legitimacy of a passage of the amendment so far beyond Congress’ deadline. Does Congress have the power to simply extend the deadline again and certify the ERA’s passage if a 38th state passes it, or did the ERA expire in 1982, rendering a 38th ratification moot?

According to a 2018 Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on the ERA and ratification issues, ERA advocates argue that a contemporary ratification is valid given Congress’ broad authority over the constitutional amendment process, including the power to extend or limit the deadline for the ERA. ERA supporters point to Article V of the Constitution—giving Congress broad power to propose amendments “whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary” and stating that proposed amendments are “valid to all intents and purposes” when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of states—to argue that Congress may extend ratification deadlines as it sees fit. Notably, Article V does include any specific time limits related to constitutional amendments, while other constitutional rules with time periods are explicitly specified. Proponents of the ERA, including Nevada’s ERA Ratification Organizer, point to the 27th Amendment’s ratification process to support an expanded—if not long—ratification process. The 27th Amendment, the most recent amendment to the Constitution imposing rules on increases or decreases to the salaries of members of Congress, was introduced in 1789, without a deadline, and was not fully ratified until 1992. ERA supporters argue that Congress can extend deadlines where the time limits appear only in the original proposing clause, not the text of the amendment itself. Finally, the fact that Congress already extended the deadline once suggests that Congress has the power to do so again.

According to the CRS report, opponents argue that despite Congress’ plenary power over the constitutional amendment process, extending the ERA deadline to allow for contemporary ratification would be unconstitutional because of ratifying states’ potential reliance on the time period in their decision to ratify. However, since the deadline was only in the proposing clause and all of the states’ ERA ratifications prior to the first deadline extension raised no constitutional issues, this argument may lack merit.

Significantly, a 38th ratification of the ERA may raise the question of whether states’ rescinding of ratifications of constitutional amendments are valid, as five states—Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee—have withdrawn their ratifications. This is not a settled area of law, but ERA proponents argue that such rescissions are not legal, as Article V provides only for ratification procedures, not rescission. The passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 lends credence to this argument, at it was certified based on the ratification of a two-thirds majority of states including Ohio and New Jersey, despite the fact that they had previously attempted to withdraw ratification. Additionally, the Supreme Court has been reluctant to weigh in on the validity of states’ ratifications of recessions of constitutional amendments. In Coleman v. Miller (1939), the Court regarded the question of the “efficacy of ratifications by state legislatures…” as a political question and did not issue a ruling on the merits. Therefore, it is likely that Congress could certify the ERA in a similar vein to the Fourteenth Amendment—that is, including ratifications from states that have since attempted to withdrawal their ratifications—legally and without intervention from the courts.