Category: Local Legislation

Protecting Vulnerable Road Users: A Vicious Cycle

Ten-year-old, Julian Moore was riding his bicycle in a suburb in Rochester, NY on Sept. 7, 2018, when 66-year-old Doug Lamb hit him with his Range Rover.

Figure 1: Julian Moore and his mother, Jenny Moore, walk near the spot where Julian was hit while bicycling. (Photo: Max Schulte/Rochester Democrat and Chronicle).

Lamb stopped the car after his collision with Moore, but did not give his information to Julian, the paramedics, or Julian’s mother. By the time the police arrived, Lamb had departed the scene. It took two weeks for the police to track Lamb down and charge him with the misdemeanor crime of leaving the scene of an accident causing personal injury. Pittsford Town Judge John Bernacki had decided to adjourn the case in contemplation of dismissal, meaning Lamb’s record would be wiped clean, on the condition that Lamb write an apology to the boy.

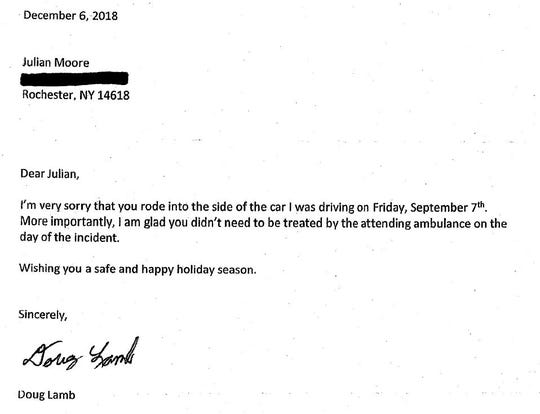

His apology letter read:

This act of “contrition” drew sweeping public scorn in January after the boy’s mother, Jenny Moore, posted a copy of the letter on her Facebook Page and the backstory subsequently made headlines around the country. In response, prosecutors moved to re-open the case and proceed to trial for failing to meet the apology requirement of his plea deal.

Prosecutor Daniel Strollo said his office pursued the case to the extent that it did because Lamb neglected to meet the condition to which he agreed to resolve the matter. “Mr. Lamb was given one simple instruction: to send a letter of apology,” Strollo said. “He didn’t do that. When you don’t follow through on the terms of a commitment for a plea or a disposition of a case, our office is not going to just ignore it.”

Lamb plead guilty on Dec. 6 in Pittsford Town Court to leaving the scene of an accident causing property damage—a mere traffic infraction. In exchange, Lamb was ordered to pay a $200 fine, perform eight hours of community service.

Julian’s story garnered national attention for his crash. Lamb was protected by a 5,000-pound vehicle of steel. Julian was protected by a plastic helmet. If it seems ludicrous the legal system could enable Lamb to walk away with a small fine and apology, it may be time to even the playing field and shift legislative protections toward vulnerable road users such as Julian.

Vulnerable Road Users

All over the country, thousands of similar crashes are occurring in the shadows, without the benefit of a national audience holding drivers accountable. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data shows 857 cyclists were killed in crashes with vehicles the U.S. in 2018. The same study found Florida leading the country with 161 of those fatalities, finding bicycle deaths for those 20 and older have tripled since 1975.

However, Florida legislators are prepared to step up and do something about the mounting problem, formally adopting “Vision Zero Florida” with a strategic goal of zero traffic fatalities and severe injuries for all users. Part of this vision includes advocacy for a proposed bill, H.B. 455 – Traffic Offenses, in the Florida Legislature which provides criminal penalties for persons committing moving violations causing serious bodily injury or death to a vulnerable road user including: a fine, period of house arrest, mandatory driver education, revocation of driver license. One of the largest shifts however, is the establishment and definition of “vulnerable road user.”

The League of American Bicyclists, a national bicycle advocacy organization, defines a Vulnerable Road User (“VRU”) as “anyone who is on or alongside a roadway without the protective hard covering of a metal automobile. The term includes bicycle riders, pedestrians, motorcyclists, people in wheelchairs, police, first responders, roadway workers and other users like a person on a skateboard or scooter. It is meant to include people who are especially at risk of serious bodily harm if hit by a car, or truck.”

VRU laws operate on the principal of general deterrence – by providing an increased penalty for certain road behaviors that lead to the serious injury or death of certain road users people will be deterred from doing those behaviors around those users.

In 2007, Oregon became the first Legislature to pass, HB 3314, creating an enhanced penalty for careless driving if it contributes to serious physical injury or death to a “vulnerable user of a public way.” Currently, only nine 9 states have laws that define a vulnerable user or VRU and provide particular penalties for actions towards those vulnerable road users or when violations of traffic law lead to the serious injury or death of a VRU – Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Maine, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, and Washington. In Texas, approximately 28 cities have passed their own VRU laws in the absence of a statewide version.

To advance this legislative effort, the League of American Bicyclists, proposes a model VRU statute for state legislatures. The model language: Section 1) defines VRU protected persons; Section 2) defines when the law is applicable and who can be charged with a violation of the law; Section 3) requires a person charged according to this law to attend a hearing; and Section 4) provides the punishments that are to be given to a person convicted of a violation of this law.

Road Ahead

Without enhanced protection for VRUs through increased penalties, it is common for a driver who kills or seriously injures a VRU to just be given a ticket for careless driving, as illustrated in a 2013 report by the Center for Investigative Reporting finding that in 238 pedestrian fatalities 60% of motorists found to be at fault or suspected of a crime faced no criminal charges.

As the closing lines of Prosecutor Strollo’s motion on behalf of Julian Moore states, “[t]he people are ready for trial.” Echoing a crystalizing national awareness that calls for increased protections to vulnerable road users, the people are ready for legislative change—and states legislatures should consider adopting a version of the VRU model law to meet this demand.

Alexandra Trobe anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Alexandra Trobe anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Electric Scooters and Data Reporting: A Roadmap to Smart Development

In many cities electric scooters appeared virtually overnight. These new forms of transportation have many benefits including: decreasing carbon emissions, making public transit more accessible, and solving first/last mile issues. Scooters also exacerbate many issues facing urban planners: taking up space on sidewalks, scaring pedestrians, increasing congestion, and may decrease public transit revenues. As state and municipal authorities scramble to regulate this new popular transportation mode, they should also embrace the benefits. A needed first step is to repurpose the Transportation Network Companies (“TNCs”) data reporting requirements to gather similar data from electric scooter companies.

In some cities TNCs, such as Uber and Lyft, contributed roughly 50% to congestion increases in the past several years. As a result, many cities and states have implemented reporting requirements on TNC’s in order to better understand their impact. In February 2019, New York City conditioned operating within the city to the disclosure of ride-share data. Now in New York City, TNCs must report: (1) where each passenger is picked up; (2) the time each passenger is picked up; (3) the total number of passengers; (4) the location where each passenger is dropped off; (5) the time each passenger is dropped off; (6) the total trip mileage; and (7) the cost of the trip. Seattle requires TNC’s to report : (1) the total number of rides provided; (2) percentage of rides completed in each zip code; (3) pick-up and drop-off zip codes; (4) percentage of rides requested but unfulfilled; and (5) collision data.

This data provides many benefits for municipal authorities. First, it allows them to better understand where trips start and end, and at what time the trips are occurring. With this information, authorities can increase and/or decrease existing public transit routes to meet demand, can extend public transit options to reach underserved areas, and adjust infrastructure to facilitate travel trends and tendencies. Public officials argue that when rider needs are better understood and this data put to an effective use, TNCs can be integrated with public transportation systems to make private car ownership obsolete, and vastly reduce traffic congestion. In turn, this would mean more efficient roads and more space for development. Additionally, less traffic would correspond to less damage on existing infrastructure, thereby opening up funding for other projects public transportation.

For example in 2018, Washington D.C., through their TNC data collection, noted that TNC usage matched transit commute patterns closely during the week, but also that TNC usage significantly increased in the evenings and weekends. In 2019, the Washington Metro proposed several potential changes to their operating hours, including significant increases to the number of service hours during nights and weekends. These changes are likely a response to insights gained from TNC data collection.

TNCs and electric scooters are similar in many regards. Electric scooters also provide an alternative transportation option that can either replace or supplement public transit. Electric scooter use can also highlight traffic trends and shed light on infrastructure and public transportation needs. For example, a study of an electric scooter pilot program in Portland, OR noted that 19% of all electric scooter trips occurred between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays, mirroring traditional rush hours. This finding parallels the findings of data collected by Washington D.C. from TNCs.

Because TNCs and electric scooters pose similar problems and could provide similar data, they should be subject to similar reporting requirements. Moreover, these requirements would not be difficult to implement as electric scooters are already GPS tracked and companies already routinely collect the data sought.

Further, this data collection could benefit the electric scooter industry. The Portland pilot program predictably discovered (1) 0% of electric scooters rode on the sidewalk when riding on a street with a neighborhood greenway; (2) 8% of electric scooter users rode on the sidewalk when riding on a street with a protected bike lane; (3) 21% of electric scooter users rode on the side walk when riding on a street with a bike land; and (4) 39% of electric scooter users rode on the sidewalk when riding on a street with no bike facilities. Consequently, Portland could, using this information and additional data about popular scooter routes, construct additional bike lanes in high scooter traffic areas to facilitate a safer commute for riders. Electric scooter data could also help municipalities determine when to increase or decrease public transit availability. If data shows a hotspot for the origination or termination of rides, authorities may even use this data to decide to expand public transit service to a previously unserved area.

Lastly, this data needs to be made available to any interested governmental entity. Although San Francisco has been plagued by TNC congestion the California Public Utilities Commission, which collects TNC data, has been reluctant to share this information with municipalities. San Francisco is unable to make informed policy decisions; regarding both TNCs and public transit generally, without this information. This hoarding of information must not happen with the data collected from electric scooters.

When regulating electric scooters, as many states and municipalities are beginning to do, they should consider requiring electric scooter companies to report on information regarding (1) passenger pickup location; (2) pick up time; (3) passenger drop off location; (4) drop off time; and (5) the total trip mileage. This information alone would give these authorities some of the data they need to better implement future transportation and municipal planning policies.

Graham (Gray) Louis anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Graham (Gray) Louis anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Dying for a Greener Tomorrow: Legalizing Alkaline Hydrolysis

From the first intentional Neanderthal burials to Polish vampire burials and Himalayan sky burials, burial practices have long been and continue to be a large part of our cultural understanding of death and the afterlife. Today’s growing concerns with land and natural resource sustainability as well as global climate change, people look towards ways to slash their carbon footprints upon death. One emerging alternative to traditional cremation is alkaline hydrolysis (also known as resomation and biocremation).

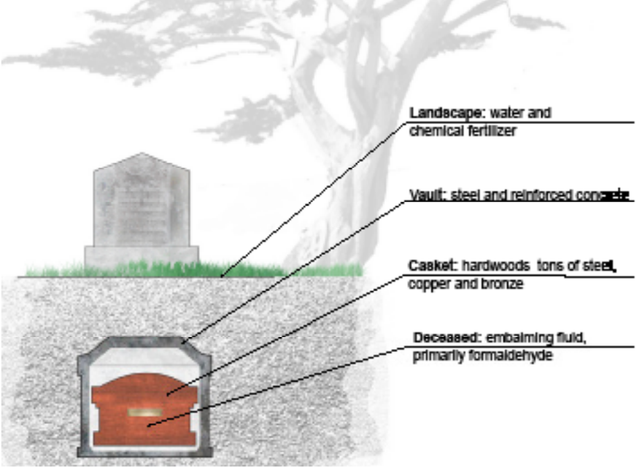

Greater than half of the US population choose conventional modern burials upon death, which includes being filled with embalming fluid, a known carcinogen, being placed into a casket composed of imported tropical hardwoods, and buried inside a concrete-lined grave. In total, conventional burials account for “4.3 million gallons embalming fluid, 827,060 gallons of which is formaldehyde, methanol, benzene, 20 million board feet of hardwoods, including rainforest woods, 1.6 million tons of concrete, 17,000 tons of copper and bronze, 64,500 tons of steel, and [c]askets and vaults leaching iron, copper, lead, zinc, cobalt” yearly in the US. The wood alone could potentially build millions of homes. Moreover, cemetery landscapers often overwater and over fertilize these spaces to keep their green appearance. On top of these environmental effects, America is running out of space for the deceased, particularly urban centers which cannot keep pace with population growth. All of this accounts for 230 pounds of carbon footprint per traditional burial, equivalent to the average American’s three month carbon output.

Figure 1. Alexandra Harker, through the Berkeley Planning Journal, illustrated the resource intensity of conventional modern burials.

Figure 1. Alexandra Harker, through the Berkeley Planning Journal, illustrated the resource intensity of conventional modern burials.

Traditional flame-based cremations, often thought of as a greener alternative, “uses 92 cubic [meters] of natural gas, releases 0.8 to 5.9 grams of mercury, and is equal to an [500 mile] car trip.” Interestingly enough, mercury dental fillings are one of the greatest concerns attributed to cremation. According to the Cremation Association of North America (CANA), “primary reasons for choosing cremation are; to save money (30%); because it is simpler, less emotional and more convenient (14%); and to save land (13%).” “The most recent figures from 2003 show that the U.S. cremation rate was 28% (700,000 cremations). Based upon increases in acceptance over the past five-year average, the . . . (CANA) has forecast a national cremation rate of 43% by 2025 with over 1.4 million cremations taking place.” Thus, finding a cost-efficient alternative might be the nation’s best bet towards a greener alternative to traditional burial and cremation practices.

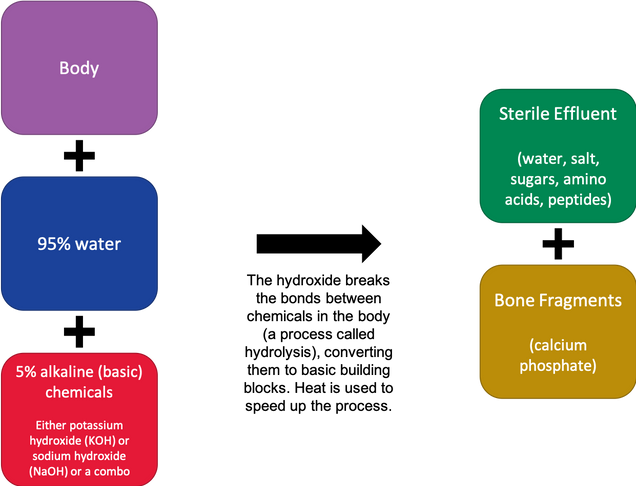

Alkaline hydrolysis reduces human remains down to bone fragments, just like the flame-based equivalent, but does so through a water-based dissolution. CANA first defined alkaline hydrolysis in 2010 as “a water-based dissolution process which uses alkaline chemicals, heat, agitation, and pressure to accelerate natural decomposition.” The removal and storage process are similar in both cremation processes, but alkaline hydrolysis provides the added benefit of allowing pacemakers and other implants in place throughout the water-based dissolution unless required by state law. However, the process of reducing the human remains through cremation is distinctly different between the two processes.

“Alkaline hydrolysis uses water, alkaline chemicals, heat, and sometimes pressure and agitation, to accelerate natural decomposition, leaving bone fragments and a neutral liquid called effluent. The decomposition that occurs in alkaline hydrolysis is the same as that which occurs during burial, just sped up dramatically by the chemicals. The effluent is sterile, and contains salts, sugars, amino acids and peptides. There is no tissue and no DNA left after the process completes. This effluent is discharged with all other wastewater, and is a welcome addition to the water systems.”

The process requires unique equipment and training, but the end result is a reduced carbon footprint. After the three to thirteen hour process of moderate heat, pressure, and agitation, the by-products are released in the water as opposed to traditional cremation which releases carbon dioxide and water vapor into the air. The water-soluble by-products include salts and amino acids, which the CANA suggests is “far cleaner than most wastewater.”

“The sterile liquid is released via a drain to the local wastewater treatment authority in accordance with federal, state or provincial, and local laws. The pH of the water is brought up to at least 11 before it is discharged. Because of the contents of the effluent, water treatment authorities generally like having the water come into the system because it helps clean the water as it flows back to the treatment plant. In some cases, the water is diverted and used for fertilizer because of the potassium and sodium content.”

Figure 2. CANA’s Board of Directors expanded the definition of cremation to include alkaline hydrolysis, mainly because the process and results were similar to traditional flame-based cremation.

Figure 2. CANA’s Board of Directors expanded the definition of cremation to include alkaline hydrolysis, mainly because the process and results were similar to traditional flame-based cremation.

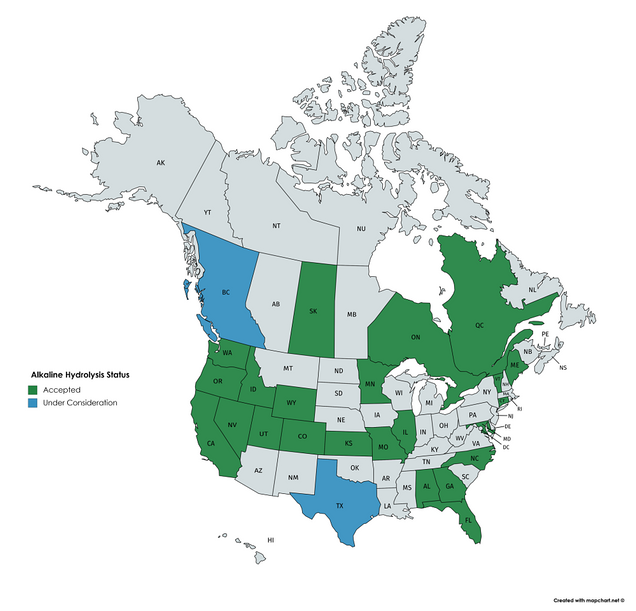

First introduced in 1888 by the farming industry for creating fertilizers from farm animal remains, the process first hit the funerary market in 2011. Today, there are twenty states and three Canadian provinces legalizing the process through legislation. Using U.S. Census Bureau July 2018 data, the twenty states’ population totals over 151.5 million citizens, which accounts for 46.3 percent of the American population. Regardless of the legalization of alkaline hydrolysis, access is today’s constraint. The legalization of the process is the first step towards the wide-spread use of alkaline hydrolysis. Once the processes are available, the price point is in line with traditional cremation services. Anderson-McQueen Funeral Homes lists the transportation, handling, and other fees associated with both cremation processes at approximately $3,000.

Figure 3. CANA keeps an up-to-date map reflecting alkaline hydrolysis regulatory changes.

Figure 3. CANA keeps an up-to-date map reflecting alkaline hydrolysis regulatory changes.

Once the wide-spread legalization of the process occurs, the public will likely push for greater access to greener cremation practices. It will be interesting to see if and when the process begins in Massachusetts and the remaining 30 states. In any case, the science shows that the massive carbon footprint that traditional burials and cremation services causes.

Tyler Heneghan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Sanctuaries With Guns? Turning The Rule Of Law Upside Down; by Delegate David Toscano (D-Charlottesville)

The Tazewell County, Virginia, Board of Supervisors recently jumped aboard the fast-moving “Second Amendment sanctuaries” train. In doing so, they embraced positions fundamentally at odds with state and federal constitutional law. Passing resolutions opposing certain laws or protesting governmental action is perfectly consistent with our traditions as a democracy, and no one should oppose the rights of citizens and their representatives to speak their minds. But Tazewell, and a number of other localities across Virginia, want to do much more. As Eric Young, an attorney and the county’s Administrator, put it, “our position is that Article I, Section 13, of the Constitution of Virginia reserves the right to ‘order’ militia to the localities; counties, not the state, determine what types of arms may be carried in their territory and by whom. So, we are ‘ordering’ the militia by making sure everyone can own a weapon." Other counties are announcing different schemes if gun safety laws are enacted: for example, the Culpeper County sheriff pledged to deputize “thousands of citizens” so they can own firearms.

Conservatives have railed for years against so-called “sanctuary jurisdictions,” criticizing localities that refuse to cooperate with federal immigration policies they deem heartless and ineffective. In the past year, however, some conservative lawmakers have taken a page from the progressive playbook, employing sanctuary imagery in opposition to gun safety legislation they deem to be an unconstitutional restriction of their rights under the Second Amendment.

The two approaches are classic cases of false equivalency. Jurisdictions that proclaim themselves sanctuaries for immigrants do not seek to violate the law; they simply refuse to engage local law enforcement in supporting actions that are federal responsibilities. They do not block the law, but simply insist that it should be enforced by those who have the responsibility to do so. For some proponents of so-called gun sanctuaries, however, the goal is to prevent enforcement of state law that the jurisdiction (not a court) deems unconstitutional.

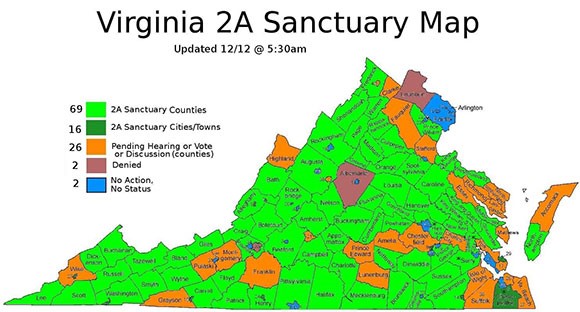

After Democrats won majorities in both chambers of the Virginia General Assembly, fears of stricter gun regulations have inspired a rise in Second Amendment sanctuary activity in Virginia. Sanctuary efforts are driven mainly by the Virginia Citizens Defense League, a gun rights group to the right of the NRA. My office’s analysis of recent news accounts indicates that before November 5, just one county had passed a resolution; since the election, at least 80 localities (counties, cities, or towns) have passed some form of sanctuary resolution, and as many as 34 more are considering their adoption.

A REBELLION EMERGES

Second Amendment sanctuaries exploded onto the national scene in early 2019 after newly-elected Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker pledged to pass gun safety measures in Illinois. Within months, 64 of the state’s 102 counties passed sanctuary resolutions. After New Mexico expanded background checks in 2019, 30 of 33 counties declared themselves Second Amendment sanctuaries. Similar actions have either been taken or are under consideration in Colorado, Oregon, Washington state, and now Virginia.

In some cases, these resolutions simply register an objection to any infringement on gun owners’ rights. But some Virginia localities have gone further, indicating that they will not enforce state law that they deem unconstitutional. Some proponents have even resurrected words like “nullification” and “interposition,” terms first used extensively by Southern secessionists prior to the Civil War, and more recently during the “massive resistance” to federal laws requiring desegregation in the 1960s. They argue that constitutional officers in Virginia, such as Commonwealth’s Attorneys and Sheriffs, have discretion not to enforce laws that they consider “unconstitutional.” In Virginia, there has always existed some debate about the independence of these officers, but, while they are creations of the Constitution, their duties are nonetheless "prescribed by general law or special act.” In short, sheriffs may be “constitutional officers,” but they are not “constitutional interpreters.”

FLASHPOINTS IN THE CULTURE WARS

The emergence of these sanctuaries demonstrates a growing rift in our nation. For residents in many rural areas of our country, guns are viewed as part of their way of life, one some fear that they will lose due to national and state changes. Most gun owners are law-abiding citizens, and any effort to limit anyone's access to firearms is perceived as a direct attack on many things that they hold dear. During the Obama years, the manufacture and purchase of firearms increased in dramatic numbers in part due to unfounded fears that the government would try to take away guns. Voting to declare themselves “sanctuaries” is a way they can reassert some control over events that they feel are putting them at risk. For these communities, it matters little that reasonable gun safety proposals have largely passed constitutional muster, or that most proponents of these measures have no intention of taking anyone’s guns away unless it can be shown, in a court of law, that they are a danger to themselves or others.

At the same time, the general public is increasingly supportive of certain gun safety measures. An April 2018 poll found that 85 percent of registered voters support laws that would "allow the police to take guns away from people who have been found by a judge to be a danger to themselves or others" (71 percent "strongly supported"). These measures, called Emergency Risk Protection Orders (ERPO), or “red flag” laws, create judicial procedures by which persons with serious mental health challenges deemed a threat to themselves or others can have their weapons removed until their situation is resolved; courts can be engaged to protect the rights of the accused. And a March 2019 Quinnipiac poll reported that 93 percent of American voters support a bill that would require “background checks for all gun buyers.”

The energy behind support of gun measures like "red flag" laws is generated by concern for mass shootings, which are statistically rare but dramatic in their public impact, and the increasing numbers of gun-related suicides, which impact families and communities in quiet but devastating ways. On the latter front, there is a certain irony that some communities which have embraced Second Amendment sanctuary status also have higher gun suicide rates than other communities in their state. In Colorado, for example, nine of the 10 counties with the highest suicide rate over the past 10 years have declared themselves “Second Amendment sanctuaries,” many after the state passed an ERPO law in 2019. Of the 24 Colorado sanctuary counties for which suicide data is available, 22 (or 92 percent) had firearm suicide rates above the state average. Similarly, in Virginia, 36 of the 51 localities that have adopted a resolution to date and for which firearm suicide data is available have rates higher than the state median.

Recent polling in Virginia tells us that citizens of the Commonwealth are in step with the national trends documented above: Roanoke College’s Institute for Public Opinion Research recently released polling results which show that 84 percent of respondents favor universal background checks, and 74 percent support allowing a family member to seek an ERPO from a court. Yet in the very same pool of respondents, 47 percent believe it is more important to protect the right to own guns than to control gun ownership. The only way to make the math add up is to recognize that some people who strongly support Second Amendment rights may also support at least some reasonable gun safety measures—an approach the “sanctuary” advocates would never adopt. But even former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia might have had problems with some of the arguments being advanced by proponents of sanctuaries. “Like most rights,” he wrote in District of Columbia et. al. v. Heller, “the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. From Blackstone through the 19th-century cases, commentators and courts routinely explained that the right was not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose." In short, rights under the Second Amendment have never been absolute. And under both the national and state Constitutions, our courts are tasked with determining the constitutionality of laws—not local sheriffs.

HOME RULE VS. DILLON RULE

Proponents of Second Amendment sanctuaries have another problem in Virginia; the Commonwealth is what we call a “Dillon Rule” state. This means that if a power is not specifically permitted to a locality, state law rules. Progressives have been especially critical of Dillon Rule arguments in years past, believing that they have prevented localities from enacting policies—from local minimum wage ordinances to gun prohibitions—that seek to go further from state law. They have rarely been concerned that more conservative localities, if granted greater “home rule,” might enact policies, such as environmental regulations or building codes, that are more lax than state law. The Second Amendment sanctuary rebellion may prompt some to reexamine their views about how much additional power should be granted to localities.

The Virginia state legislature will soon consider several major gun safety measures, and opponents will likely strongly resist; as one county supervisor has said, “[W]e need to show them a crowd like they have never seen. They need to be afraid and they should be afraid.” Legislators should always be attuned to any unintended consequences of the laws that they pass; that is one reason why we have a deliberative process before bills are passed. But to leave the determination of whether to enforce duly-passed laws totally in the hands of sheriffs and local officials with discretionary power to determine their constitutionality is to turn the rule of law upside down, and is a direct attack on republican government and the Constitution itself.

David Toscano has represented the 57th district in the Virginia House of Delegates since 2006, and from 20011-2019 Del. Toscano served as the House's Democratic Leader. His forthcoming book is titled, In the Room at the Time: Politics, Personalities, and Policies in Virginia and the Nation.

A modified version of this opinion piece appeared on Slate.com.

Blanket Primaries or Ranked-Choice? Why Not Both?

A substantial number of Americans continue to voice dissatisfaction with current American electoral practices. This has put Justice Brandeis’s laboratories of democracy to work by prompting some states to exercise their powers to design election systems to experiment with various electoral reforms. Those powers derive from the state constitutions for elections of state officers; Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution to “[prescribe] the Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives”, and the U.S. Constitution Article II, Section 1 to determine how electors for President may be chosen.

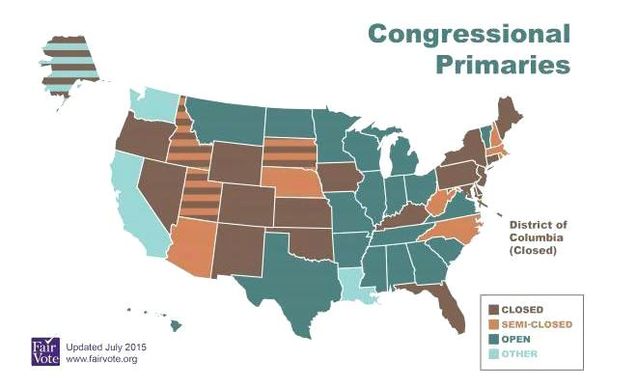

Many states have allowed their municipalities to experiment, with a few states adopting reforms on a state-wide level. In the latter category, some states, like California and Washington, have adopted what is sometimes described as the top-two, blanket, or Louisiana primary, while Maine has implemented ranked-choice voting. While these reforms have been innovative, study of their effects reveals limited success in achieving advocates’ promises. This post concludes that by combining both reforms, states will be better positioned to access the positive outcomes hoped for.

Blanket Primaries

Former Republican congressman from Oklahoma, Mickey Edwards, has argued that the problem with American politics is our  broken election system that rewards partisanship at the expense of good policy. Edwards argues that the culprit is the primary. Primary election turnout is notoriously low, with a recent Pew Research Center study celebrating a surge in participation in the 2018 House primary elections of 56% - a surge that still left turnout in that primary under 20%. The belief is that since political participation in primaries is so low, they are dominated by the most active, and most partisan, members of the parties, limiting the success of more centrist candidates, who are presumably more representative of their districts. In particularly politically active years, incumbents are at risk of being “primaried” by extremists in their party. Thus, the candidates in the general election tend to be more extreme, on both ends, than the district, and the eventual winner is then likely to represent only one extreme, rather than the district as a whole.

broken election system that rewards partisanship at the expense of good policy. Edwards argues that the culprit is the primary. Primary election turnout is notoriously low, with a recent Pew Research Center study celebrating a surge in participation in the 2018 House primary elections of 56% - a surge that still left turnout in that primary under 20%. The belief is that since political participation in primaries is so low, they are dominated by the most active, and most partisan, members of the parties, limiting the success of more centrist candidates, who are presumably more representative of their districts. In particularly politically active years, incumbents are at risk of being “primaried” by extremists in their party. Thus, the candidates in the general election tend to be more extreme, on both ends, than the district, and the eventual winner is then likely to represent only one extreme, rather than the district as a whole.

To address this concern, Edwards advocates for a reform known as “blanket” primaries, sometimes referred to as “Louisiana,” “jungle,” or, most accurately, “top two” primaries. This reform provides that in the primary election, there is a single ballot, with all candidates on the ballot regardless of party. The top-two candidates who receive the most votes then move on to the general election. This means that the candidates in the general election may both be from the same party, particularly in districts whose residents heavily identify with one party over the other. This may make for more competitive general elections, in that a candidate who is almost certain not to win isn’t on the ballot, in favor of a candidate who actually has a chance of convincing voters to vote for them. Also, along with Edwards’s hope that this will reduce partisanship by ensuring the candidates in the general election better represent the center of the district, advocates have also claimed that it will increase turnout.

Unfortunately, the data provides only marginal support for the proposition that blanket primaries reduce partisanship and increase turnout. An added challenge to blanket primaries is that because only the top-two move on, it is subject to vote splitting – if too many candidates from a party enter the race, they may end up without any candidates in the general simply by virtue of the number of candidates in the race, rather than voter preferences. Thus, blanket primaries are not a panacea, at least on their own, for electing more representative representatives.

Ranked-Choice Voting

Maine has moved in a different direction, adopting ranked-choice voting (“RCV”), a darling of electoral reform advocates for decades. RCV has a long pedigree, first having been promoted publicly in the United States by William Robert Ware in the 1870s. Some states and municipalities flirted with a version of RCV, known as single transferable vote, in the last great shift in party power during the early- to mid-twentieth century. RCV and similar systems have also been successfully used internationally – including in Australia, and Ireland.

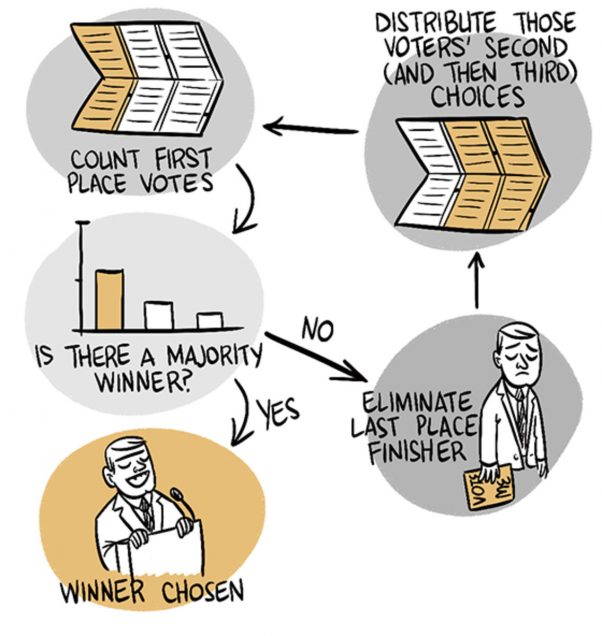

While there are many different iterations of ranked-choice voting, Maine has adopted the most typical approach. There, voters may rank candidates first, second, third, and so on. If a candidate gets a majority of first-rank votes, they are declared the winner. However, if no candidate receives a majority of votes, then the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated, and the voters who ranked that candidate first have their votes redistributed to their second-rank candidates. If no candidate has a majority, the new candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated, and their voters’ ballots are also redistributed. The system continues until a candidate has secured a majority of preferences.

Advocates of ranked-choice have also claimed that the system reduces partisanship, since candidates are encouraged to appeal to voters to rank them second, even if they can’t secure their first preference. Advocates also argue that it increases turnout by

making the ballot more reflective of voters’ wishes. As with blanket primaries, however, there is only modest statistical data showing that the turnout hopes are borne out.

A Proposal

States should consider merging the two systems, blanket primaries and RCV, in order to best access the benefits of each. The real problem that neither system effectively can address is the issue of turnout. Primary elections typically draw the most politically aware sector of the electorate that is most invested in who the candidates in the general election are, but turnout remains exceedingly low regardless of the system. Blanket primaries attempt to appeal to an electorate disenchanted by the current partisan model and looking to elect “the best candidate,” but since they continue to rely on a two-stage electoral model, they don’t resolve the fundamental problem. The most partisan members of the electorate participate in the blanket primary, and turnout surges, as it always does, in the general, after the partisans have already selected who will be on the ticket. Combining ranked-choice with the blanket primary would allow there to be a single election, ensuring the highest number of voters considering all the available candidates, not just those the partisans have already selected. Moving to a single election, with candidates on a single ballot regardless of party, and using RCV would ensure that the larger electorate would be able to weigh-in, allow them to rank their preferences, and ensure that the candidate who emerged was the preferred candidate of a majority of voters. This will increase elected officials’ mandate, and provide more information about what direction the district would like to go in.

Massachusetts Regulates Short-Term Rentals

Massachusetts’s Governor Baker signed An Act Regulating and Insuring Short-Term Rentals on December 28, 2018. The act regulates short-term rentals provided through services like Airbnb. The governor rejected an earlier version of the bill, and returned amendments primarily allowing for an exemption for owners who rent out their property for two weeks or less per year, and reducing the amount of information provided publicly about rentals owners. The bill was motivated by concerns that the rise in short-term rentals drives up housing costs and pushing out long-term residents. The statewide bill comes after both Boston and Cambridge individually passed laws essentially having the same effects. However, the Boston law was challenged by Airbnb, who filed suit in federal court claiming that the regulations are “Orwellian” and violate several laws, including laws that protect online companies from being held liable for the actions of their users. The city of Boston is currently holding off on some of the regulations passed pending the resolution of the court case. Airbnb had not yet said if it will challenge the new Massachusetts law.

The statewide law has two main components: first, that all short-term rentals are taxed by the Commonwealth, and can be additionally taxed by local governments, and second, that all owners of short-term rental properties must register with the state and hold insurance. The registration requirement was a cause of debate.  Lawmakers, including Governor Baker, were concerned about violating the privacy of owners by publishing their names and addresses publically. In the amendments to the July bill that Governor Baker rejected, the registration requirement was changed so that only the owner’s neighborhood and street name would be published, not their exact address. The law also dictates eligibility in order to register. To be eligible to be a short-term housing unit, the space must be compliant with housing code, be owner-occupied and be classified for residential use, among other requirements. Another cause of debate was an exemption for occasional renters. Governor Baker originally wanted owners who rent their properties for 150 days or less to be exempt from the regulations. However, in the final version of the bill, the exemption was decreased to 14 days.

Lawmakers, including Governor Baker, were concerned about violating the privacy of owners by publishing their names and addresses publically. In the amendments to the July bill that Governor Baker rejected, the registration requirement was changed so that only the owner’s neighborhood and street name would be published, not their exact address. The law also dictates eligibility in order to register. To be eligible to be a short-term housing unit, the space must be compliant with housing code, be owner-occupied and be classified for residential use, among other requirements. Another cause of debate was an exemption for occasional renters. Governor Baker originally wanted owners who rent their properties for 150 days or less to be exempt from the regulations. However, in the final version of the bill, the exemption was decreased to 14 days.

Not surprisingly, the hotel industry supports the bill. Paul Sacco, the President and CEO of Massachusetts Lodging Association, said:

“This is a tremendous victory for municipal leaders and the people of Massachusetts who have been waiting for years while Airbnb rentals have exploded, resulting in skyrocketing housing costs and disruptions in local neighborhoods. By adopting a more level playing field between short-term rentals and traditional lodgers, lawmakers made great strides toward a more fair and sensible system.”

Airbnb had a far less enthusiastic response however. In citing concerns about the property owners who use Airbnb to earn extra income, Airbnb said that they would “continue the fight to protect our community and the economic engine of short-term rentals for hosts, guests, and local small businesses”

While Massachusetts is the first state to pass a law, many other cities have passed similar laws in the recent years. In Nashville, the city passed a law in January which focused on taxing short-term rentals that are not owner-occupied in order to fund affordable housing development in the city. The “linkage fee” tax is controversial, with lawmakers questioning if the fees generated are enough to actually impact the lack of low-income housing within the city. Seattle passed a similar tax law in November 2017. The legislation aims to encourage owners who rent out a spare bedroom and discourage investors who buy entire buildings for use as short-term rentals. Finally, New York City passed regulations in July 2018 which requires Airbnb, and other similar companies, to provide information about the properties listed for rental within the city. However, Airbnb sued in federal court claiming that the requirement to provide information to the city violated the company’s fourth amendment right against search and seizure. The law was set to take effect in February 2019, however the Judge granted a preliminary injunction in favor of Airbnb saying, “The city has not cited any decision suggesting that the government appropriation of private business records on such a scale, unsupported by individualized suspicion or any tailored justification, qualifies as a reasonable search and seizure.”

Jessica A. Hartman is a member of the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020.

Jessica A. Hartman is a member of the Boston University School of Law Class of 2020.

Mental Illness and Gun Violence: What’s Really Responsible?

You’ve heard it all before. In fact, you’ve heard the same arguments repeated back and forth so many times you have memorized them yourself. The cycle goes like this: There’s a mass shooting, then in the tragic aftermath, the liberal and conservative pundits begin repeating their arguments left and right. Usually, on the conservative right there are calls for mental health reform and on the left, liberals agree that we need to address mental health, but point to gun access as the key issue to prevent these tragedies from happening. The rest of us, the general population, are left somewhere in between. We point fingers like everyone’s to blame, but we take action like nobody is responsible. That is to say, we take very little action at all.

Although this cycle has repeated itself to the point of feeling like a broken record, it’s important that we not get stuck like one. After all, the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over-and-over again while expecting a different result. Where some blame the mentally ill and some blame guns, it is important to step back and reframe our arguments to see the issue of gun violence in a different light. Maybe the solution, as is often the case, lies somewhere in between.

The tragedy in Parkland has energized this debate to unprecedented levels, but has also brought with it many familiar arguments. In particular, recent calls from President Trump to strengthen limitations on the ability of the mentally ill to access firearms gives us cause to reevaluate his premise that mental illness is associated with gun violence. President Trump’s critique is founded on a commonly shared belief among the majority of Americans. According to a Pew Research poll in 2017, 89% of people across the political spectrum favor placing increased restrictions on the ability of the mentally ill to purchase firearms. This commonly held belief across the political spectrum forces us to ask ourselves: What is the real relationship between mental illness and gun violence?

What do the Numbers Say?

The evidence suggests that we may be biased when it comes to our perceptions of the mentally ill and the potential for persons dealing with mental illnesses or disorders to exhibit violent tendencies. In fact, a 2013 national public opinion survey (p.367) found that 46% of Americans believe that persons with mental illness are “far more dangerous than the general population.” However, the public perspective is vastly distinct from reality. Another study (p.241) demonstrates that between 2001 and 2010, “fewer than 5% of the gun-related killings in the United States… were perpetuated by people diagnosed with mental illness.” People are far more likely to be killed by a person with a gun that does not have a mental illness, than someone that does have a mental illness.

While mental illness is not strongly correlated with gun violence, there are other conduct measures that appear to be strong predictors of such violence. Three conduct measures in particular that are powerful are past acts of violence/criminal history, a history of domestic violence, and substance abuse.

First, with regard to a history of violence, the American Psychology Association issued a report (see p.8) that concluded based on longitudinal studies, “The most consistent and powerful predictor of future violence is a history of violent behavior.” One article from Wisconsin Public Radio affirms this trend in reporting that for gun homicides in Milwaukee about, “93 percent of our suspects have an arrest history.” Although the Milwaukee sample is small and not entirely representative of the entire United States, such a high correlation is worthy of our attention in considering factors for reevaluating our gun policies.

Second, when it comes to the correlation between domestic violence and mass shootings or gun violence, the evidence is even stronger. According to a study quoted in the New Yorker, “Of mass shootings between 2009 and 2013, 57 percent involved offenders who shot an intimate partner and/or family member.” Further, a report from Everytown for Gun Safety shows that persons with a history of domestic violence account for “54 percent of mass shootings between 2009 and 2016.”

Third, with regard to substance abuse, a study (p.242) by Dr. Jonathan Metzl, an often quoted figure in studying the causes of gun violence in the United States, found that, “[A]lcohol and drug use increase the risk of violent crime by as much as 7-fold, even among persons with no history of mental illness.” According to the same study, “serious mental illness without substance abuse is ‘statistically unrelated’ to community violence.” In other words, substance abuse increases an individual risk of violence in general, including an increased risk of gun violence.

States Offer Pragmatic and Nuanced Solutions

However, correlation does not equal causation. Many of the current studies on the causes of gun violence and mass shootings face limits (p.240) in this particular regard. However, the low statistical correlation indicated in multiple studies between mental illness or disorders and gun violence are informative. The fact that there are other risk factors that are strong predictors of violence generally and gun violence specifically point to where our attention is likely better directed in trying to rework gun laws in a manner that will work for everyone.

The Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence points to one such unique legal mechanism adopted in Oregon, Washington and California, which have adopted laws for Extreme Risk Protection Orders (“ERPOs”). These laws allow family members or law enforcement officers to petition a court to keep guns away from someone going through a crisis. The laws are geared toward the principle that family members are best able to gauge changes in an individual’s behavior that could pose a serious risk of harm. Petitioners under these laws still have the burden of providing sufficient proof that the individual poses a risk of danger to themselves or others. ERPOs are also only temporary, but may vary in length. For longer protective orders, more compelling evidence must be offered that the person poses a risk of harm to themselves or others.

Oregon offers another pragmatic solution in its closing of the “domestic abuser loophole” through passage of a recent state law. Under the 1996 Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban, domestic abusers are banned from owning or possessing a gun. However, the federal ban only applies to someone if they are married, living with, or have a child with the victim of the abuse. The wording of the law creates the “domestic abuser loophole,” which means that someone who is not living with their significant other and does not meet any of the other mentioned criteria, but who abuses their significant other, can still buy a gun. Oregon’s new law prohibits anyone convicted of a crime of domestic violence from owning or possessing a gun, regardless of whether or not that person lives with their significant other.

These new state laws are just examples of a number of other pragmatic and nuanced policy solutions that are geared toward preventing future gun violence while avoiding burdensome restrictions on the Second Amendment rights of the vast majority of Americans. Such solutions demonstrate our capacity to tackle the problem of gun violence in new and creative ways, while still preserving individual freedoms. Finally, these laws represent effective solutions that are based on empirical evidence about true risk factors for gun violence and not on ill-founded stigmas. A path forward on fixing our gun laws exists, but to move forward we must set aside our preconceived notions and work together to promote innovative solutions that protect both our rights and our safety.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

Nicholas Stone graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018 and plans to practice in Portland Oregon.

Footloose in New York City–The Repeal of the Cabaret Act

The 1984 film, Footloose, imagines the small, midwestern town of Bomont, where dancing and rock’n roll music have been banned, only to be redeemed in the end by a teenager’s impassioned plea. Footloose’s plot may seem farfetched but a law with similar intent has gripped New York City since 1926 when the city passed the Cabaret Act. Under the Cabaret Act, any place open to the public that sells food or drinks, alcoholic or not, including “pubs, taverns, and discos,” are required to obtain a license if they want to allow dancing in the establishment. One of the pre-requisites for a cabaret license states that “cabarets” must have video surveillance and security on the premises at all times. However, after 90 years of forcing most of its bars and nightclubs to effectively operate like the clandestine prom from the end of Footloose, New York City Council member Rafael Espinal and Mayor Bill de Blasio have finally brought dancing back to New York City.

The cost of obtaining a cabaret license was inexpensive, ranging from $150 to $1,250 (with minor additional costs), but the process required to get a license and to meet the accompanying surveillance requirements were particularly onerous. To obtain a cabaret license, an establishment had to submit extensive and intrusive records about both the business and building where the establishment is located, as well as receive approvals from the Fire Department, a licensed electrician, and the local Community Board. Due to these overwhelming requirements, and a lack of consistent enforcement, there were only 104 licensed “cabarets” in the entirety of New York City as of 2017. Most establishments where dancing occurs are unlicensed and can potentially be subject to severe penalties.

The cost of obtaining a cabaret license was inexpensive, ranging from $150 to $1,250 (with minor additional costs), but the process required to get a license and to meet the accompanying surveillance requirements were particularly onerous. To obtain a cabaret license, an establishment had to submit extensive and intrusive records about both the business and building where the establishment is located, as well as receive approvals from the Fire Department, a licensed electrician, and the local Community Board. Due to these overwhelming requirements, and a lack of consistent enforcement, there were only 104 licensed “cabarets” in the entirety of New York City as of 2017. Most establishments where dancing occurs are unlicensed and can potentially be subject to severe penalties.

The Cabaret Act, as originally passed, was a blatantly racist law, targeting African American jazz clubs in Harlem. When passing the law, the Board of Alderman used coded racist language in their rationale, referring to the individuals going to the dance halls as “wild people.” At the same time, the Aldermen exempted large hotels in upper class, primarily Caucasian areas, from the licensing requirement. Until 1967, the law also required musicians who played in establishments with liquor licenses to obtain “cabaret licences” as an individual. As the process of obtaining a musician license required a criminal background check and could be revoked for almost any reason, many prominent jazz musicians were unable to perform in New York City clubs, including Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Thelonious Monk.

check and could be revoked for almost any reason, many prominent jazz musicians were unable to perform in New York City clubs, including Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Thelonious Monk.

While New York City officials have occasionally made concerted attempts to crack down on unlicensed “cabarets,” wider scale closure movements occurred in the aftermath of nightclub fires in 1976, 1988, and 1990. For long periods of the Cabaret Act’s history, there was almost no enforcement at all, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s. However, beginning with Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s election in 1994, New York City began to strictly enforce the cabaret law as part of Mayor Guiliani’s quality-of-life initiatives. Through his Multi-Agency Response to Community Hotspots, or MARCH, Mayor Guiliani directed several municipal agencies to scrutinize establishments for violations, with the purpose of curtailing the city’s nightlife. Some people believe that Mayor Guiliani’s strict enforcement of the cabaret law contained a racial element similar to the law’s original intent.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration continued Mayor Guiliani’s crackdown on New York City’s nightlife, employing the cabaret law as well as noise ordinances and a ban on smoking in public places, to severely limit the proliferation of nightclubs. Towards the end of his tenure in office, Mayor Bloomberg considered repealing the cabaret law but ultimately failed to do so. Following his election, Mayor de Blasio relaxed enforcement of the cabaret law and, and after over 90 years, repeal finally became a reality.

In 2017, City Council member Rafael Espinal introduced several bills to reform New York City’s nightlife, including repealing the Cabaret Act. On September 19, 2017, Mayor de Blasio signed bill number 1688-2017 - which amends the New York City charter, in relation to establishing an office of nightlife and a nightlife advisory board - into law. The law establishes a Nightlife Advisory Board and an Office of Nightlife to examine the issues affecting the city’s nightlife and to make recommendations to the Mayor for improvements. The bill passed almost unanimously, with only City Council member, Rosie Mendez, voting in the negative.

The Cabaret repeal, bill number 1652-2017 subchapter 13, however, retains similar security and surveillance requirements to those under the Cabaret Act, including having video surveillance cameras and security guards in all nightlife establishments with dancing. The bill defines a nightlife establishment as one that is “(i) open to the public after 12:00 a.m. at least one day each week; (ii) is required to have a license to sell liquor at retail pursuant to the alcohol beverage control law; and (iii) satisfies at least two of the following factors: 1. At least 2500 square feet of such establishment is open to the public; 2. Has an occupancy load of at least 150 persons as described on the certificate of occupancy; or 3. Imposes a fee for admission at least once a week.”

On November 27, 2017, Mayor de Blasio signed Int. 1652-2017, officially repealing the Cabaret Act. de Blasio stated, “This law just didn’t make sense. Nightlife is part of the New York melting pot that brings people together. We want to be a city where people can work hard, and enjoy their city’s nightlife without arcane bans on dancing.”

In March 2018, Mayor de Blasio appointed the City's first "Night Mayor," Ariel Palitz. Mayor Palitz will be paid $130,000-a-year to lead the newly created Office of Nightlife that has a $300,000 annual budget. Palitz is the former owner of now-closed East Village nightclub Sutra, which was once labeled the city’s loudest watering hole.

It appears that New York City is finally free of its connection to the fictional town of Bomont.

Peter Lubershane anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Peter Lubershane anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

WHO LET THE DOGS OUT? CALIFORNIA BANS USE OF PUPPY MILL

In October 2017, California became the first state to pass a law to deter the use of puppy mills by potential puppy buyers. Under the new law, pet stores must work with animal shelters and other rescue operations to obtain dogs, cats and rabbits, and are prohibited from using breeders. However, private and individual customers can still use puppy mills, and nothing in the act adds direct regulations on domestic animal breeders in the state.

Over the past several years, there has been a nationwide conversation among pet lovers about the ethics of puppy mills. At the center of the debate is the competition for owners between adoption/rescue groups, and breeders. According to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), 34% of currently owned dogs were raised by a breeder, as opposed to 23% coming from an animal shelter or other humane rescue group. Origination data is not entirely clear however, as the American Humane Association (AHA) and the American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA) put breeder-acquired ownership figures at less than 20%. Shelter-based ownership figures vary even more, with the AVMA putting the adoption population at 84.7% and the AHA estimating a 22% adoption population. Available figures for breeder-acquired cats are below 5%. While it is difficult to claim that adoption and rescue agencies are at a disadvantage for owners strictly because of breeder competition, the sheer number of pets in shelters (5-8 million dogs and cats) and getting euthanized every year (3-4 million dogs and cats), makes many wonder why people use breeders at all. Proponents of laws like California's believe that people who buy breeder-bred animals could have instead adopted an animal from a shelter.

Over the past several years, there has been a nationwide conversation among pet lovers about the ethics of puppy mills. At the center of the debate is the competition for owners between adoption/rescue groups, and breeders. According to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), 34% of currently owned dogs were raised by a breeder, as opposed to 23% coming from an animal shelter or other humane rescue group. Origination data is not entirely clear however, as the American Humane Association (AHA) and the American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA) put breeder-acquired ownership figures at less than 20%. Shelter-based ownership figures vary even more, with the AVMA putting the adoption population at 84.7% and the AHA estimating a 22% adoption population. Available figures for breeder-acquired cats are below 5%. While it is difficult to claim that adoption and rescue agencies are at a disadvantage for owners strictly because of breeder competition, the sheer number of pets in shelters (5-8 million dogs and cats) and getting euthanized every year (3-4 million dogs and cats), makes many wonder why people use breeders at all. Proponents of laws like California's believe that people who buy breeder-bred animals could have instead adopted an animal from a shelter.

Another facet of the “puppy mill” debate is the living conditions in breeder facilites. Claims of animal cruelty plague the reputation of breeder businesses. Though breeder operations are governed by Federal USDA regulations and inspections, irresponsible breeders can evade these oversights and sell animals that have been bred improperly, leading to pets with physical and psychological ailments. Many times, these irresponsible breeders will focus on quantity, instead of quality of the animals (hence the term “mills”) possibly leading to poor health, abandonment, or even death of the animals. Since these disreputable breeders often sell to pet stores, instead of directly to screened buyers, laws like the one California just passed will likely serve as a significant deterrent for negligent breeders. However, some detractors of the bill say many cities statewide (including LA, San Diego, and San Francisco) already ban “mass breeding” and other unhealthy practices, so this new law is more likely to constrain the breeders who do not engage in these poor practices, yet sell to pet stores, than the irresponsible breeders.

Aside from animal welfare, steering potential pet owners and pet shops to animal shelters should benefit the state’s taxpayers. Publically run animal shelters cost the state approximately $300 million a year. If this law has its intended effects and decreases overcrowding in animal shelters, the state can accordingly decrease spending on housing, feeding, and servicing shelter animals. While California may pinch some pennies with decreased animal shelter populations, the breeding community may suffer economically under this bill. California has roughly 800 active breeders selling animals in the state. Even if only a small percentage are fully reliant on pet stores for income, that is still dozens of California’s workers being effectively forced out of a job under this law. However, some of this job loss may be offset by impacted breeders selling to out-of-state pet stores who do not have similar laws.

Though California’s new law was a key win for anti-puppy mill and animal welfare advocates, there are still some detractors. For example, this law may present challenges to those seeking specific breeds for their pet. Consumers may no longer easily get breed specific animals in pet stores, and specific breeds may become more costly. This might be particularly cumbersome for someone looking for a service animal of a particular breed best suited to help manage a condition. The American Kennel Club released a statement saying the law “not only interferes with individual freedoms, it also increases the likelihood that a person will obtain a pet that is not a good match for their lifestyle and the likelihood that that animal will end up in a shelter.” Further, this legislation may have the unintended consequence of increasing animal deaths and abandonment at puppy mills, because the mills no longer have access to their main customers. If the mills have not sold off all their animals by the 2019 effective date of this law, the animals may have nowhere to go. Breeders whose business is hurt as a consequence of this law may spend even less money on the care of the animals, or be forced to surrender the animals to a shelter. But given the delayed effective date of the law and the continued legality of breeder use by individual parties, the foreseeable issues will likely be negligible in light of the positive changes.

Since California passed this law, a Massachusetts lawmaker has also proposed a similar bill that would deter the practice of commercial breeding. Though California is the first state to pass this kind of prohibition, cities all over the country have been passing similar ordinances, so it is likely that states will follow suit if California’s law works as intended.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Negotiating with Goliath: Lawmakers’ battle with Uber & Lyft over ridesharing legislation

As I stepped off the plane and into the jet bridge, I already had my Uber app opened on my smartphone, and only a few short minutes after requesting a ride, the driver was calling me to tell say that he was outside baggage claim. This kind of convenience and ease that e-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft provide is what we have grown accustomed to as consumers.

E-hailing companies, or transportation network companies (TNCs), have made finding a ride very convenient for city dwellers and travelers alike. Whether it is one of the main players like Uber or Lyft, or one of the newer startups like Juno, Fasten, or Gett, TNCs have become an integral part of how we travel and for some of us, our everyday lives.

As convenient as TNCs are, legislatures across the country have made it clear that these companies will not be free from regulation. Rather, city and state legislatures have proposed legislation that will both allow TNC, but also protect riders.

In early February 2017, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie signed a new law making the Garden State the most recent of the 36 states to regulate TNCs. This new law, the Transportation Network Company Safety and Regulatory Act, which is similar to Massachusetts’s 2016 law, requires that TNC companies cover up to $1.5 million dollars in liability insurance and that drivers get background checks. However, TNC drivers are still not subject to the same fingerprinting background checks as taxi drivers. Additionally under the law, the public still does not have access to the safety records of drivers, a concession made by lawmakers in its negotiations with Uber. Municipalities are also prohibited from taxing TNC companies, promoting a more uniform single statewide regulation.

The New Jersey legislation did not come without a fight, however, with Uber demanding limits to regulations. In fact, Uber, throughout its many negotiations with city and state legislatures around the country, has consistently threatened to withdraw all of its business in the city or state at issue if the legislature does not adopt its preferred regulations. This is especially true when it comes to the fingerprinting requirement, which Uber particularly opposes. According to Uber, requiring drivers to get fingerprinted would make it harder to recruit drivers. Uber also claims that the requirement would be unfair to minority applicants, as fingerprint background checks only indicate arrests, not convictions, and false arrests are more frequent in minority neighborhoods.

Prior to the enactment of New Jersey’s statewide law, Uber had been in contentious negotiations with many New Jersey cities including Newark, the State’s largest city by population. In the end, Newark and Uber were able to come to an agreement, and Newark passed a now pre-empted ordinance where Uber would pay Newark $10 million in fees, and drivers would be required to get background checks by a nationally accredited third-party, but there would be no fingerprinting requirement.

Austin, Texas, however, had a different experience. Austin’s city council passed an ordinance requiring driver background checks with fingerprinting. Rivals Uber and Lyft joined forces and campaigned for Proposition 1, which would repeal the ordinance. The two companies spent $8 million dollars on advertising, or $200 per vote to get their message across. Yet, the campaign failed to sway voters, and Proposition 1 lost 44% to 56%. The day after the election, Uber and Lyft made good on their threat to withdraw their services from the area, leaving drivers and riders unable to use either app in the Austin area. Uber did the same to other Texas cities Midland, Corpus Christi, and Galveston, leaving because it did not agree with the local ordinances that had been passed.

Ending service so abruptly had a negative impact on riders who had become accustomed to this mode of transportation and drivers who relied on both companies for a source of income. Austin eventually set up a hotline and job fair for these suddenly out-of-work Uber and Lyft drivers. Luckily for Austin, riders and drivers were not left out in the lurch for too long, as entrepreneurs and new e-hailing companies quickly filled the void left by the two giants. Uber and Lyft left on May 9th and by the summer, there were ten companies who were set up and ready to compete. More than that, these new companies were able to get roughly 9,000 drivers to sign up and all of the companies met the August 1 deadline to have at least half of their drivers fingerprinted. All of the companies had to be in full compliance with the ordinance by February 1, 2017.

Ironically, these hard-fought battles between Uber and Lyft and America’s largest cities might all be for naught. Despite Austin’s city council’s win in keeping their city ordinance on the books, the state legislature passed, and on May 29th Governor Greg Abbott signed, a statute that pre-empted Austin’s ordinance. Since a local government only has the authority granted to it by the state, when state and local laws conflict, the local law will typically be pre-empted. Abbott stated, "In Texas we don't believe in heavy-handed, top-down, one-sided regulatory environm

ents that erect barriers for businesses, in Austin, Texas, we're going to override burdensome, wrongheaded regulatory barriers that disrupt the free-enterprise system upon which Texas has been based and upon which has elevated Texas to be the No. 1 state in the entire country for doing business." Texas joined other states, which have increasingly preempted local ordinances. The most recent and notable example is North Carolina’s HB2 law, which pre-empted Charlotte’s anti-discrimination ordinance.

Pre-emption in regards to TNC legislation may not be so terrible, however. There is a great benefit to both the state and companies to have one standard rather than multiple municipal ordinances. With a service such as ridesharing, it is not uncommon for someone to be picked up in one town and dropped off in another. Because of this reality, it may be preferable for the states to take the lead.

New Jersey's law shows the trend is certainly moving in the direction of state legislation, not municipal. However, now the question is will state legislatures remain strong in their positions or will they give in to what Uber and Lyft demand? As we have seen in Austin, there will always be a new company who is willing to comply with the new regulations if Uber and Lyft will not. Therefore, perhaps states should pass the ideal legislation that they feel best protects its citizens and let the market sort itself out. Uber and Lyft have a lot of negotiating power because they are the biggest players, but as we have seen, they do not have an impenetrable monopoly. As the city of Austin found out, the TNC market will not crash if Uber and Lyft leave. There are plenty of worthy “Davids” who would jump at the chance to fill the void of Goliaths Uber and Lyft, even if in the face of stricter regulation.

Merissa Pico is from Fort Lee, New Jersey and graduated summa cum laude from Boston University’s College of Communication in 2015 with a B.S. in Mass Communication Studies. She is expected to earn her J.D. from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Merissa will be working at Ropes & Gray in New York City in the summer of 2017 and is looking forward to continuing to explore her interests in entertainment and communications law.

Merissa Pico is from Fort Lee, New Jersey and graduated summa cum laude from Boston University’s College of Communication in 2015 with a B.S. in Mass Communication Studies. She is expected to earn her J.D. from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Merissa will be working at Ropes & Gray in New York City in the summer of 2017 and is looking forward to continuing to explore her interests in entertainment and communications law.