Tagged: Boston University Law School

July 10th, 2018

in Analysis, State Legislation

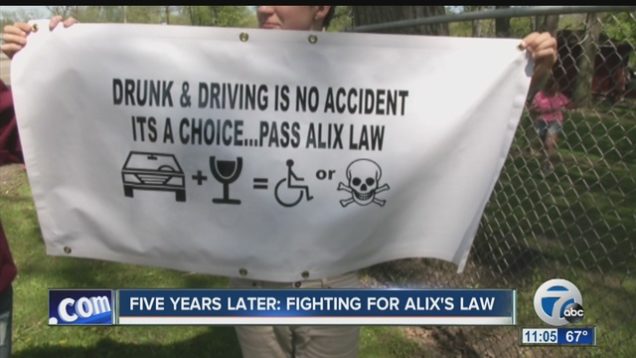

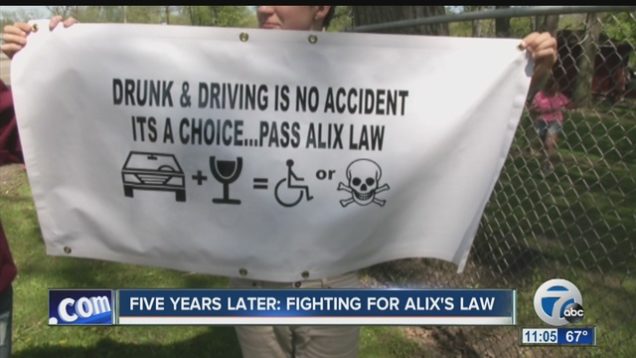

On the night of July 8, 2011 18 year-old Alexandria “Alix” Rice died on the side of the road in a town just outside of Buffalo, New York. Alix was riding her longboard home from work around 11:20 pm when a drunk driver hit her and sent her flying 150 ft. from the point of impact, breaking both of her legs, some ribs, and lacerating her cerebellum. The driver, Dr. James Corasanti, a 55 year-old gastroenterologist sped away from the scene leaving Alix to die. Alix did not die alone though. Another motorist and his wife stopped to help Alix after seeing a car speeding towards Alix and then hearing an “almighty bang,” a sound the witness described as “ungodly.” Other residents of the usually quiet street reported hearing a “loud thump,” a “horrific noise,” and a “jarring sound” and many came out to help Alix. Dr. Corasanti however, did not stop. He drove home, cleaned Alix’s blood and flesh from the front of his $90,000 BMW, deleted some text messages, called an attorney, and 91 minutes later, turned himself into police.

Alix Rice

At the police station Corasanti refused to submit to a blood test to determine his blood-alcohol level. Five hours later law enforcement officers were able to get a court order for Corasanti’s blood, which registered a .10 blood-alcohol content, .02 above the legal limit. Prosecutors charged Corasanti with second-degree manslaughter, second-degree vehicular manslaughter, leaving the scene of an incident without reporting, resulting death, tampering with physical evidence, and misdemeanor driving while intoxicated. During the trial experts testified that Corasanti’s BAC was likely between .14 and .21 when he hit Alix Rice. Evidence showed Corasanti had been texting and speeding when he hit Alix, though there was disagreement as to whether Corasanti crossed over into the bicycle lane where Alix was riding or if she had crossed into the road when she was hit. Yet, despite the significant weight of the evidence, Corasanti was acquitted of all charges except the misdemeanor DWI.

Dr. James Corasanti was drunk, texting, and speeding when he hit Alix Rice and left her for dead on the side of the road. How was he able to avoid all felony charges, including leaving the scene of an incident without reporting? The answer; a loophole in the law that only requires a driver to stop if they know or have reason to know that a person has been injured, or that damage has been done to property as a result of a motor vehicle accident. The current law gives drivers an incentive to leave the scene of an accident because in order to convict, prosecutors must prove that anyone in the driver’s position must have known that they hit a person. Corasanti and his defense team were able to convince the jury that there was reasonable doubt as to whether Corasanti knew that he hit a person. Corasanti claimed that his BMW was designed to cancel out noise and therefore he did not hear the impact of his car hitting Alix’s body. Dr. Corasanti was sentenced to one year in jail despite killing Alix Rice.

Lawmakers and the public were outraged. Looking for a way to close the loophole that allowed Corasanti to receive such a minimal sentence, New York State Senator Patrick Gallivan introduced Alix’s Law, Senate Bill 7577-A in 2012. Alix’s Law is designed to prevent drunk drivers from hitting something or someone, leaving the scene, and then being able to claim that they did not know that any injury or property damage occurred. The bill holds drunk drivers responsible for leaving the scene of an accident. Alix’s Law, adds the following language to the current statute:

Lawmakers and the public were outraged. Looking for a way to close the loophole that allowed Corasanti to receive such a minimal sentence, New York State Senator Patrick Gallivan introduced Alix’s Law, Senate Bill 7577-A in 2012. Alix’s Law is designed to prevent drunk drivers from hitting something or someone, leaving the scene, and then being able to claim that they did not know that any injury or property damage occurred. The bill holds drunk drivers responsible for leaving the scene of an accident. Alix’s Law, adds the following language to the current statute:

“A person operating a motor vehicle in violation of section eleven hundred ninety-two of this chapter that came into contact with a person, real property, or personal property, that resulted in damage to real property or to the personal property, not including animals of another, shall be presumed to have known or have cause to know of such contact and of such damage, unless such person shows that they would not have known or had cause to know of such contact and of such injury regardless of intoxication or impairment by the use of alcohol or a drug.”

The new language creates a rebuttable presumption that an intoxicated driver who is involved in an accident knows that they have caused damage or injury and therefore they must stop and report the accident to police. The current law is the opposite. In order to convict someone for leaving the scene of a fatal accident, the prosecution has the burden of proving that the driver knew or should have known that they hit a person. This law makes it easier to prosecute people for leaving the scene of an accident they caused while driving drunk. Alix’s Law passed in the Senate on June 19, 2012 and was sent to the Assembly where it died in the Transportation Committee.

Alix’s law was reintroduced in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Each year Alix’s Law has received unanimous, or near unanimous support from the Senate. In 2016, Alix’s Law passed 58-0 in the Senate before it stalled in the Assembly. In 2017 Sen. Gallivan introduced Alix’s Law for the 6th time as S. 3393-A. The same bill was introduced in the Assembly as A.1944 by Assemblywoman Crystal Peoples-Stokes. Alix’s Law passed 61-0 in the Senate in 2017, but again died in Assembly. Alix’s law was returned to the Senate, and as of February 6, 2018, it was back in the Senate Transportation Committee.

New York State Capitol

Albany 1899

It is not clear why Alix’s Law has yet to move out of committee in the Assembly after passing unanimously on six different occasions in the Senate. Assemblywoman Peoples-Stokes told reporters that counsel for the committee has advised that Alix’s Law is unnecessary and that the law already covers what Alix’s Law is trying to change. However, a former acting Erie County District Attorney points out that the law would change the incentives for people to leave the scene of an accident, and would help close the loophole that allowed Dr. Corasanti to avoid felony charges. Additionally, there have been a number of high profile hit-and-runs in the past few years, and so it may be time for the legislature to take action and to address the problem. Whether or not Alix’s Law will ever pass the assembly is yet to be seen, but Sen. Gallivan and the Rice family continue to advocate for Alix’s Law and are committed to keeping Alix’s memory alive.

Meghan Hayes anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Meghan Hayes anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Tagged Alexandra Rice, Alix's Law, Boston University, Boston University Law School, drunk driving, New York Assembly, New York Senate, texting while driving

July 10th, 2018

in Analysis, Federal Legislation

In February 2018, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, the federal agency that grants green cards and U.S. citizenship, revised its mission statement by striking its characterization of the United States as a “nation of immigrants.” The phrase dates back to the 1800s and was popularized by President John F. Kennedy, who sought to remind Americans of the monumental contributions that immigrants have made to America. The removal of this iconic language is consistent with the President Trump’s “America first” agenda, including efforts to limit immigration by proposing to end or alter the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, ban immigration from several majority-Muslim countries, and build a wall along the Mexican border. This anti-immigration attitude has also led to attempts to curtail the family visa program, which allows U.S. citizens and permanent residents to sponsor certain family members applying for lawful permanent residency in the United States.

President Trump recently made immigration policy a priority with congressional leaders at Camp David, emphasizing his desire to end the “horrible system” of family sponsored visas, which he refers to as “chain migration.” Now, in exchange for softening their proposal to deport DACA recipients, President Trump and the Republicans are targeting the lower priority F3 and F4 category family visas, arguing that they threaten national security. In fact, President Trump blamed chain migration, also known as “family reunification,” for the terrorist attack on New York City in December 2017. The perpetrator of that attack entered on an F43 visa, the lowest priority family visa category reserved for children of parents who are sponsored by a direct relative who is a U.S. citizen. While the U.S. issues an unlimited number of visas to close relatives of U.S. citizens, the number of visas allotted for extended family, or “chain migrants,” is capped at 226,000 per year.

The political rhetoric surrounding chain migration has stoked fears about national security and who is entering the United States through family sponsored visas. But historically, the concept of chain migration was actually simpler and less nefarious than it has recently become. The term “chain migration” was coined as a politically neutral term in the 1960s and stands for the proposition that people are more likely to move to where their families live. Although opponents of family sponsored immigration often use “chain migrant” to denote any immigrant relative of a green card holder or U.S. citizen, the modern technical usage refers to extended relations and not immediate family.

Interestingly, conservatives originally supported family sponsored immigration through the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965. The Act replaced the nationality quota system, which many viewed as overtly racist, with the family reunification program. Around 1960, immigration from Europe began to decline as the continent became more prosperous. Conservatives hoped that the new program would encourage European immigrants to bring their families to the United States. Today, only about eleven percent of immigrants are European, with forty-four percent coming from Eastern Europe, including First Lady Melania Trump and her parents. Meanwhile, the overall majority comes from Asia and Latin America.

Interestingly, conservatives originally supported family sponsored immigration through the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965. The Act replaced the nationality quota system, which many viewed as overtly racist, with the family reunification program. Around 1960, immigration from Europe began to decline as the continent became more prosperous. Conservatives hoped that the new program would encourage European immigrants to bring their families to the United States. Today, only about eleven percent of immigrants are European, with forty-four percent coming from Eastern Europe, including First Lady Melania Trump and her parents. Meanwhile, the overall majority comes from Asia and Latin America.

While concerns about protecting national security are real, the visa category is not as important as the screening process itself. The screening process for family sponsored visa applicants is extensive. Applicants must submit to background checks and be evaluated on the likelihood that they will become an economic liability to the state. In addition, immigrants must have a financially stable relative vouching for them, with a household income of at least 125% of the poverty line including the visa applicant. Finally, because of nationality caps and visa backlogs, it can take many years to bring extended relatives to the United States. This limits the potential to build chains of immigrants, especially from countries like Mexico that have many more qualified applicants than distributable visas.

Although no safeguard is perfect, the potential for chain migration to overwhelm the U.S. is more limited than the Administration’s rhetoric would suggest. Unfortunately, this raises the question whether the fierce opposition to immigrant families is truly about security, or whether a fear of cultural and ethnic change is prompting the effort to end the family reunification program.

As of 2014, Hispanics and Asians are the fastest growing groups in the nation for two separate reasons. Hispanics have a higher fertility rate once they arrive in the United States, while Asian immigrants arrive in the greatest numbers. Meanwhile, the percentage of white Americans is declining. All of this suggests that immigration is making America more diverse and less familiar to white Americans, who make up eighty-one percent of the 115th Congress but just sixty-two percent of the U.S. population. In the House of Representatives, Democrats have eighty-three minority members while the Republicans have only twelve, despite holding forty-five more seats as of January 2018.

It is unclear how the Democrats will handle Republicans’ demands for ending the F3 and F4 family sponsored visa programs. Eliminating those visas may be the price of protecting the 800,000 individuals enrolled in DACA. However, Republicans have also run into trouble with this negotiation tactic. As recently as April 25, 2018, a federal judge in the D.C. Circuit decided that the DACA program must remain intact unless the Department of Homeland Security can explain why DACA is “unlawful” within ninety days. If the courts uphold DACA then its effectiveness as a bargaining chip against the family sponsored visa program is greatly diminished.

As an alternative to chain migration visas, President Trump has proposed both cutting immigration overall by forty-four percent over the next fifty years, and shifting to a merit-based immigration system. Republicans have also introduced bills to limit family sponsored immigration and increase the number of merit-based employment visas. Democrats are unlikely to accede to cutting immigration so drastically, and shifting to a merit-based system could imply breaking up families. However, the merit-based system has been successful in Canada, where emphasis on immigrant contributions has popularized immigration as a whole. In fact, Canadians feel significantly more positive about immigration than do many Americans. Canada proportionally accepts about three times more immigrants than the United States, but saves about two-thirds of the slots for merit-based applicants. This may have economic advantages, but it raises humanitarian concerns. On the other hand, if the alternative is slashing immigration across the board, then it might be a necessary compromise. Switching to a merit-heavy system, however, may signal an end to the democratic values of an America that once prided itself, at least superficially, on welcoming the tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

Caitlin Britos anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Caitlin Britos anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Tagged Boston University, Boston University Law School, chain migration, DACA, family visa program, ICE, Immigration, Trump

July 10th, 2018

in Analysis, Federal Legislation, State Legislation

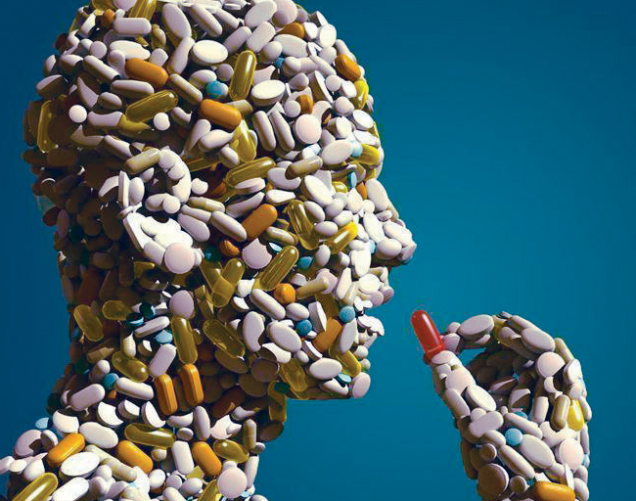

The Opioid Epidemic stands apart from past drug crises this country has experienced. Not only is this the deadliest drug crisis the country has experienced, this epidemic is a result of a “perfect storm.” A shift in the medical field to focusing on the treatment of pain changed opioid prescribing practices and encouraged an increase in marketing practices of opioid pharmaceutical companies, resulting in America being the world’s leader in opioid prescriptions. Congress, through the Bipartisan Task Force to Combat the Heroin Epidemic, made some progress addressing opioids during the Obama Administration, but with the change in administration the efforts seem stalled.

In 2015, doctors prescribed enough opioids to medicate every American around the clock for three weeks. Even as doctors started to prescribe fewer opioids, in 2016 enough opioids were prescribed to fill a bottle for every adult in America. The increase in opioid prescriptions came at the same time as there was a shortage of workers in addiction and recovery, allowing for only 10 percent of Americans with substance use disorder to receive the necessary treatment. This “perfect storm” created a massive swell in opioid addictions. As it became more difficult to obtain prescription opioids, addicts sought a stronger high and many turned to illegal opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl. Nearly 80 percent of Americans addicted to heroin started with misuse of prescription drugs.

The death of Philip Seymour Hoffman in 2014 from a heroin overdose put a spotlight on the crisis. Despite recognizing that there was a nation-wide epidemic, the country took a lackluster response and overdose deaths continued to spike. The National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse have reported only an increase in the overdose deaths. The U.S. government estimated about 64,000 overdose deaths for 2016. With the epidemic claiming a record number of lives per day, all of the 2016 presidential candidates spoke about personal stories or plans of action for combatting the epidemic. Most of the candidates agreed that the federal government should provide resources to the states to help combat the epidemic with a focus on treatment. Some of the other candidates focused on stopping the flow of drugs coming across the border, including now President Donald Trump.

In March 2017, President Trump established the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. The Commission members include Former Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey, Governor Charlie Baker of Massachusetts, Governor Roy Cooper of North Carolina, Former Congressman Patrick Kennedy of Rhode Island, Professor Bertha Madras, and Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi. On November 1, 2017, the Commission issued a final report with more than 50 recommendations (see, page 7). They included increasing data sharing of state-based prescription drug monitoring programs, changing privacy regulations to allow healthcare providers easier access to information about patients with substance use disorder, equipping all law enforcement officers with naloxone, and enforcing the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. In addition, the Commission recommended a national multi-media campaign to help fight the epidemic, more federal funding for the states, drug courts in every federal district court, and enhanced penalties for drug trafficking to reduce the supply of opioids.

Even prior to the issuance of the report, President Trump declared the Opioid Epidemic a public health emergency. The President stated “[t]he best way to prevent drug addiction and overdose is to prevent people from abusing drugs in the first place. If they don’t start, they won’t have a problem,” but until his 2019 budget proposal the President’s Administration failed to request funding to combat the epidemic. Congressman Patrick Kennedy, a vocal critic of the limited action taken by the President, explained, “[t]he emergency declaration has accomplished little because there’s no funding behind it. You can’t expect to stem the tide of a public health crisis that is claiming over 64,000 lives per year without putting your money where your mouth is.”

The President’s focus has been on increasing funding for law enforcement. On January 10, 2018, the President signed the INTERDICT Act which provides funding to U.S. Customs and Border Protection to assist with the detection and interception of illicit fentanyl. Increased enforcement may be part of the solution, but some Congressional leaders believe there is more than just one solution and have said the epidemic must be addressed on many fronts.

In 2015, Representatives Ann McLane Kuster and Frank Guinta from New Hampshire, a state that has the highest fentanyl overdose deaths per capita, created the Congressional Bipartisan Task Force to Combat the Heroin Epidemic. From its inception, the task force has gained members from both parties, and now has more than 100 members. The Task Force pushes a legislative agenda, as well as holds informational hearings. Under President Obama’s Administration, the Task Force was able to pass several pieces of legislation, including the 21st Century Cures Act, and the Comprehensive Addiction & Recovery Act (CARA). The CARA Act is currently the main source of funding for the opioid epidemic, but the funding will run out in 2018. In response to the “perfect storm” that created this epidemic, CARA has six pillars of response, including prevention, treatment, recovery, law enforcement, criminal justice reform, and overdose reversal.

On January 10, 2018, the Task Force released its 2018 legislative agenda. The agenda includes bills focusing on prevention, treatment, law enforcement, and prescribing practices. Several of the bills include federal funding and grants. After the Task Force called for an increase in funding to combat the epidemic, Congress passed $6 billion in the 2018 budget. Some have been critical of the amount of funds dedicated to the epidemic, and compared it to the $24 billion a year that was dedicated to addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis.

On February 9, 2018, Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, announced it had laid off employees whose job was direct promotion of the drug to doctors. Purdue Pharma is currently facing dozens of lawsuits for deceptive marketing practices. It is unclear if the company’s change in promotion practices will alter prescribing practices of doctors, who are already familiar with the drug. To make a significant impact on the epidemic, real change needs to happen outside of Purdue Pharma’s promoting practices.

The U.S. Surgeon General issued a public health advisory encouraging Americans to routinely carry naloxone on April 5, 2018, which is the first advisory issued since the 2005 warning against drinking alcohol while pregnant. Access to naloxone would come in part from the $6 billion in the 2018 budget which has allocated grants for naloxone so states can hand it out for free; however, there is also reliance on naloxone manufacturers keeping costs low. The Surgeon General explained that naloxone can be a “touch point that leads to recovery.” However, more in line with the Trump Administration, the Surgeon General believes that the involvement of law enforcement is necessary to solving the epidemic.

A tough-on-crime approach and focus on providing funding strictly for law enforcement, as President Trump has encouraged, is not the answer. The country responded to the crack cocaine drug crisis with a tough-on-crime approach and strict sentencing guidelines. That led to extraordinary incarceration rates, especially for African Americans, and failed to address the issue of addiction as a disease. The country should learn from its mistakes, take a more well-rounded approach, as suggested by the Surgeon General and the Bipartisan Task Force, and implement a long-term solution. Congress must not only provide funding for law enforcement, but should increase treatment and recovery for substance use disorder, implement better prescription drug monitoring programs, start country-wide drug court programs, and educate Americans and doctors about the disease of addiction and risk of opioids. People are dying every day in this country from opioid overdoses, and every time Congress delays we lose another life.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Mikayla Foster anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Tagged Boston University, Boston University Law School, Comprehensive Addiction & Recovery Act, drug crisis, heroin, naloxone, opioids, President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, Surgeog General Advisory

July 10th, 2018

in Analysis, Federal Legislation, State Legislation

Data breaches are a growing and ongoing concern. As of the modern economy relies more heavily on web-based services, hackers throughout the world are finding innovative ways to exploit this new technology for their own gain. The big question is: will Congress act to address the problem?

Recent data breaches have drawn the ire of members of Congress, including the Equifax hack and Facebook’s privacy issue with Cambridge Analytica, largely because of perceived wrongdoing or an inadequate response on the part of the breached company. Data breaches are tricky because, on the one hand, the breached company is the victim of a criminal act which should be investigated and prosecuted. But, on the other hand, to the extent that a company is breached because it was negligent or even reckless in failing to patch a known security flaw, some kind of legal consequence seems appropriate. Crafting a legislative response to address data breaches is an intricate matter that begins with an important question: as a matter of federalism, are data breaches a state or federal concern?

A vast majority of states have laws on the books requiring a breached company to take some kind of action after a security breach. These laws define “personal information” and require that notice of the breach is given to either breached consumers or a state government entity such as the Attorney. States wielding their police power to regulate the response to data breach incidents makes sense because data breach litigation is usually focused upon a theory involving negligence, privacy invasion, or breach of a fiduciary duty (Solove & Citron, at 8). Each of these causes of action are firmly rooted in state law. Yet, the patchwork approach to data breach legislation leaves many companies scrambling to comply with very different laws in the various jurisdictions where individuals with breached data reside.

Yet, many data breaches end up litigated in federal court. The most common reason for this is the Class Action Fairness Act (28 U.S.C. §§ 1332(d), 1453(b); “CAFA”), which provides a federal forum to claims where the parties maintain minimum diversity (at least one plaintiff located in a state different from at least one defendant) and an amount in controversy of at least $5 million. Because many data breaches impact a disparate plaintiff class residing throughout the country, and because the sought-after remedy is much larger than $5 million, these cases are frequently removed to federal court.

Other data breaches are litigated in federal court from the start, with causes of action arising under federal statutes. Claims are often brought under Fair Credit Reporting Act (15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq., “FCRA”), which requires companies that send information to credit reporting agencies to take “reasonable procedures” to protect the confidentiality of sensitive personal information. The federal government also regulates data security in several industries, including the healthcare industry through the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (Pub. L. 104–191, “HIPPA”) and the financial services industry through the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (Pub. L. 106–102, “GLBA”). Lastly, the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) regulates some data security matters pursuant to the agency’s authority to prosecute unfair competition.

These statutes make clear that the federal government has some role to play in the data security sphere, and with good reason – data security can quickly become a matter of national security. First, many data breaches are thought to involve state-sponsored actors, implicating international law and sovereignty concerns. Next, data breaches can give rise to other federal crimes, including identity fraud (Internet Research Agency Indictment; Counts 3-8 at ¶¶ 96-98). When that identity fraud was apparently perpetrated with an intent to interfere in America’s free and democratic elections, the concern is only exacerbated.

So, what can Congress do to address this issue? While the problem is very complex and requires an equally complex response, Congress often prefers to address problems in a piecemeal fashion. There have been two bills put forth, one from Senators Nelson, Blumenthal, and Baldwin, and another from Senators Warren and Warner. It is important to note that the two bills cover different topics under the greater umbrella of data privacy – they are not mutually exclusive and they are not merely two different solutions to a single problem.

Senator Nelson’s bill, called the Data Security and Breach Notification Act, would require the FTC to establish minimum “policies and procedures regarding information security practices for the treatment and protection of personal information.” § 2(a)(1). This bill includes provisions that exempt financial institutions in compliance with GLBA, but it covers a large number of different organizations and industries. It also creates a series of new penalty provisions authorizing fines up to $5 million for infractions. Notably, § 7(a) dictates that this bill would preempt state information security laws. This provision is sure to be unpopular with certain states, especially those (like Massachusetts) that have been proactive in regulating data at the state level (see the testimony of Sara Cable, Assistant Mass. AG, to the U.S. House of Representatives’ Financial Services Committee, Part II.C, page 4).

Senator Warren’s bill has a narrower scope, addressing only “credit reporting agencies” with annual revenue “not less than $7 [million]”. § 2(4). After the Equifax breach announced in the Fall of 2017, the credit reporting agencies themselves became the focus of new scrutiny. Given the immense volume of sensitive information that these agencies possess, and their critical role in our financial system, it makes sense that these entities should satisfy more exacting standards. Senator Warren’s bill would establish an “Office of Cybersecurity” within the FTC, and that office would be charged with promulgating regulations and investigating non-compliance with those regulations. §§ 3(b)(B), (D). The bill also contains a fairly restrictive notification requirement – mandating that covered credit reporting agencies alert customers within 10 days after a breach. § 4(a). Such notification requirements present interesting policy question. On the one hand, the sooner customers know of a breach, the sooner they can take action to prevent identity theft and fraudulent use of their finances. On the other hand, in countries like Australia that have recently implemented mandatory notification laws, companies have expressed concern that such a notification would amount to an “admission of guilt” that may come back to haunt the company in subsequent litigation.

Though there are many issues underlying data privacy and security, one thing is clear – something must be done. Because these bills address different areas of cybersecurity, they should both pass. Even if that were to happen, much more needs to be done. States undoubtedly have an important role to play, but it is much faster and more efficient for federal legislation to address an issue like this that impacts citizens nationwide. But, what precisely needs to be done, however, is a much more complex question. The 115th Congress has been derided for its lack of action on many important issues, including an immigration fix for DACA recipients and addressing firearms in the aftermath of the Parkland shooting. So, will anything actually happen? Only time will tell.

David Bier plans to graduate from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

David Bier plans to graduate from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Tagged Boston University, Boston University Law School, Cambridge Analytica, Cyber Security, cybersecurity, data, Data Security and Breach Notification Act, Equifax, FTC

June 28th, 2018

in Analysis, Legislative Operations

In my last post, I argued that the process of drafting new legislation should be undertaken with a problem-solving mindset. I suggested that problem-solving tools from a variety of disciplines could be advantageously adapted to the legislative process. In this post, I will present the manner in which one specific tool—Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)—could be used in legislative drafting.

FMEA was originally developed as a tool to improve processes within the manufacturing industry. An FMEA is a “systemic method of identifying product and process problems before they occur.” Robin E. McDermott, Raymond J. Mikulak, Michael R. Beauregard, The Basics of FMEA 3 (1996). (Many of the details of the FMEA process discussed in this post come from The Basics of FMEA. I highly recommend that anyone interested in performing FMEAs in the legislative process read this book. The steps of an FMEA can be found in the book or online, here.) In the manufacturing context, the goal of an FMEA is to figure out how a new product or process is likely to fail, before that failure happens, and then to recommend improvements that will preemptively prevent the failure. In FMEA terminology, the process is designed to identify and resolve “failure modes” in a product or process.

In the legislative context, a bill working its way through the legislature can be thought of as the new “product or process” to which an FMEA can be applied. In this post, I will discuss where in the legislative process an FMEA could be performed, what the make-up of an FMEA team might be, and what beneficial output could be expected from an FMEA.

The authors of The Basics of FMEA, recommend that “[i]deally, FMEAs are conducted in the product design or process development stages, although conducting an FMEA on existing products and processes may also yield huge benefits.” The Basics of FMEA at 3. Likewise, a legislature could use FMEAs to analyze already existing laws. However, in this post, I will only describe FMEAs that would take place during the drafting process. Such an FMEA would likely be most useful to the legislative process after a committee performs hearings and before it votes on a bill. At this point, the committee has already gathered a wealth of useful information and the legislature still has wide latitude to make changes to the bill when potential failure modes are discovered.

The FMEA team itself should consist of four to six members. Id. at 15. Idealistically, the team will “bring a variety of perspectives and experiences to the project.” Id. This will likely result in team members having varying degrees of expertise in the relevant subject matter and a range of familiarity with the legislation being reviewed. For example, an FMEA team for a bill related to criminal justice might include: a legislative attorney familiar with the bill, a representative from the police force, an associate district attorney, a public defender, and representatives from advocacy groups or lobbyists. It is worth noting that many of the individuals on the team may be the same individuals who provided testimony in a committee hearing. Such overlap does not diminish the unique value that can be obtained by an FMEA. Likewise, an FMEA would in no way detract from the value of the committee hearing. Committee hearings give advocates an opportunity to state their case and respond to questions from members of the committee. The FMEA would give these individuals an opportunity to interact with one another and to work towards improving legislation in ways in which they can all agree.

It is also important to note that many of the FMEA team members may also represent the individuals that the law is meant to address—the “role occupants” and implementing agencies. See Ann Seidman & Robert B. Seidman, Instrumentalism 2.0: Legislative Drafting for Democratic Social Change, 5 Legisprudence 95, 95 (2011). The Seidmans note that a role occupant’s failure “to respond to a law’s commands, prohibitions or permissions, signifies . . .

that, in drafting the bill’s detailed prescriptions, the drafter failed adequately to take into account the relevant constraints and resources in the role occupant’s environment.” Id. at 136. Bringing representatives of role occupants and implementing agencies into the legislative process via FMEAs would help to reduce these drafting failures.

Of course, the ultimate language of a bill must be determined by legislators and legislative attorneys. Nevertheless, the recommendations of an FMEA team regarding specific bill language could be of significant help to those tasked with the actual drafting of the bill. An appropriate balance of power between drafters and the FMEA team can be established by providing FMEA teams with “clearly defined boundaries within which they are free to conduct the FMEA and suggest and implement solutions.” The Basics of FMEA at 20-23. For example, the scope of a drafting-focused FMEA could be limited to the language of the bill, excluding considerations of the substantive legislative plan embodied in the bill. While a broad legislative scheme may be well suited to effectuate desired change, the language of a bill may fail to adequately implement the legislative plan. Such an FMEA could identify, document, and recommend corrections to any problematic drafting discovered. Once the bill is revised, the FMEA team could re-convene and repeat its analysis.

Whenever a new step is added to a process, a fear may arise that the process is becoming more complex, and therefore less efficient. The inclusion of FMEAs in the process of drafting legislation would undoubtedly require legislative drafters to overcome a steep learning curve. Once that learning curve is overcome, however, use of the FMEA methodology will yield significant benefits. In the short term, the FMEA could uncover and correct potential problems in a bill before it leaves its committee. In the long term, effective FMEAs would decrease the likelihood that laws would need to be revised to address problems that were not foreseen during the drafting process. Idealistically, the end result will be a more efficient legislative drafting process resulting in the passing of better drafted laws.

Andrew P. McDonough graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Andrew P. McDonough graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Tagged Boston University Law School, BU Law, evidence-based legislation, Failure Modes and Effects Analysis, FMEA, ILTAM, Professor Ann Seidman, Professor Robert Seidman

June 28th, 2018

in Analysis, State Legislation

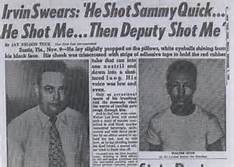

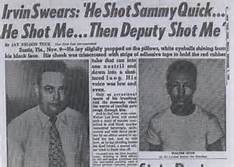

In April 2017, the Florida legislature passed a resolution (HCR 631) formally apologizing for the unjust prosecution and persecution of the “Groveland Four”, and calling for their exoneration by Governor Rick Scott. The “Groveland Four” is the popularized moniker for Charles Greenlee, Walter Irvin, Samuel Shepherd, and Ernest Thomas; four young black males (age 16 and up) accused of raping a 17-year-old white woman in Groveland, 1948. The infamous case took place during the Jim Crow era, following generations of wrongfully accused, wrongfully prosecuted, wrongfully convicted, and wrongfully executed black citizens. Shortly after they were accused of the crime, Samuel Shepard and Walter Irvin, both World War II veterans, were abducted by law enforcement officers and taken to a secluded spot to be beaten and tortured. After this assault, the deputy officer took Shepard and Irvin to the scene of the crime, only to find that their shoes did not match the footprints that allegedly belonged to the true assailants. Frustrated, the officers took Shepard and Irvin to an interrogation room where they were beaten and tortured until they confessed.

Eventually, Charles Greenlee was picked up by the authorities and subjected to the same treatment a

Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin in custody

Shepard and Irvin, but Ernest Thomas caught wind of the investigation and attempted to flee. Thomas’s flight incited a lynch mob, led by both the local sheriff’s department as well as the Ku Klux Klan. The mob not only hunted down and killed Thomas over 200 miles away, but also terrorized the black, segregated section of Groveland, burning down the suspects’ houses and causing numerous black residents to abandon the city in fear. Sheriff Willis McCall, though complicit in stirring up some of chaos, attempted restoring a semblance of order by having the remaining suspects moved from the local jail to the state prison to await trial. The NAACP and the FBI got involved with the case as national attention grew. After documenting the beatings and torture by local law enforcement, the FBI recommended that the Tampa U.S. Attorney General bring charges, but no indictments were made. Franklin Williams of the NAACP represented the remaining suspects, and through his own investigation, suspected the rape accusation was actually a cover-up of a domestic violence incident between the accuser and her boyfriend. During the trial, there was evidence that the suspects had not been in town during the incident and that the footprint (which never matched the suspects’ shoes) was fabricated by the deputy. Still, an all-white jury found Shepard, Irvin, and Greenlee guilty within minutes of deliberating, sentencing Shepard and Irvin to death, and 16-year-old Greenlee to life in prison.

The United States Supreme Court overturned the capital convictions (Greenlee never appealed) and remanded the case for retrial. Sheriff McCall was transferring Shepard and Irvin back to Lake County (Groveland’s county) for the trial, when McCall claimed he was attacked by the two black men and forced to shoot them in self-defense. Fortunately, Irvin survived the multiple gunshots and told his version of events, which included an unprovoked execution of Shepard and collusion between McCall and his deputy to cover up the failed execution of Irvin. At the retrial, eventual first black Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall represented Irvin, but faced problems similar to the first trial, and Irvin was sentenced to death again. The Florida governor spared Irvin and commuted his sentence to life in prison; Irvin went on to spend 14 years in prison and was released in 1968. He fled Florida for Tennessee, but came to visit Lake County in 1970, where he was found dead in his car. Greenlee was eventually released.

The United States Supreme Court overturned the capital convictions (Greenlee never appealed) and remanded the case for retrial. Sheriff McCall was transferring Shepard and Irvin back to Lake County (Groveland’s county) for the trial, when McCall claimed he was attacked by the two black men and forced to shoot them in self-defense. Fortunately, Irvin survived the multiple gunshots and told his version of events, which included an unprovoked execution of Shepard and collusion between McCall and his deputy to cover up the failed execution of Irvin. At the retrial, eventual first black Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall represented Irvin, but faced problems similar to the first trial, and Irvin was sentenced to death again. The Florida governor spared Irvin and commuted his sentence to life in prison; Irvin went on to spend 14 years in prison and was released in 1968. He fled Florida for Tennessee, but came to visit Lake County in 1970, where he was found dead in his car. Greenlee was eventually released.

Irvin with his lawyers Alex Akerman, Thurgood Marshall, Paul Perkins and Jack Greenberg

The terrible saga of the Groveland Four is only a snippet of the corruption and racism that plagued Lake County, Florida, and the criminal justice system as a whole during and after Jim Crow. Still, this recent formal apology only follows after mounting public pressure to acknowledges the horrendous wrongs of the state. In 2012, the same year Greenlee died, the book Devil in the Grove, which tells the story of the Groveland Four, came out. This book not only renewed interest in the case, but also won a Pulitzer Prize. The book drove a University of Florida student to launch a massive Change.org petition, and with the help of the Miami Herald and Greenlee’s daughter, the matter of an apology and exoneration finally reached a boiling point. Now that an acknowledgment and formal apology has passed the legislature, the wronged accused’s families – and history itself – await the posthumous exoneration by the governor.

If the governor eventually exonerates these innocent African Americans, after waiting over a year to do so, it would follow a growing trend of acknowledging the terrible failures of the criminal justice system and political leaders during the 20th century. However, given the quantity and severity of these failures, should leaders be taking more active steps to right these egregious wrongs, instead of simply apologizing and exonerating? While surviving family members of these victims may be gladdened by a formal acknowledgement of the truth, should they be compensated for their generational pain and suffering, lost wages, even lost earning potential? The impact of these unjust persecutions is not limited to their historical time period, nor to the victims’ families – the community, and even the whole nation, felt the repercussions of these state sanctioned racist acts. These acts also highlight glaring failures of accountability and checks and balances in the criminal justice system. Politicians score political points for acknowledging their state’s past, without taking proactive measures to prevent the same injustices in the future. Civil rights activists believe lawmakers should do more than just apologize, and instead commit resources to ensuring citizens are educated about these dark corners of history, as well as reforming law enforcement offices to ensure accountability and true justice. Others believe that the apologies are not even necessary; what happened in the past should remain there, and present-day America should not apologize for the sins of its fathers. Either way, as the nation reconciles more of these injustices, lawmakers should be thinking of ways to protect their constituents from future injustice.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Tagged Boston University Law School, BU Law, civil rights, Florida, Gov. Rick Scott, Groveland Four, wrongful conviction

June 28th, 2018

in Analysis, Federal Legislation

On December 20, 2017 Congress passed H.R. 1, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This act introduces the most sweeping tax changes in decades lowering individual and corporate tax rates, with one stated goal of allowing buyers to write off the costs of new investments. In relevant part, this Act introduces one provision that removes a favorable tax rate for innovators with self-created intellectual property and eliminates the ability to treat certain self-created intellectual property as capital assets.

Under the prior tax scheme, self-created intellectual property would have been subject to the capital gains tax rate following sale of those assets. However, Section 1221 of the Internal Revenue Code under the new law exempts self-created intellectual property from capital gains treatment.

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

Effectively, the sale of self-made intellectual property typically will now be subject to the higher top individual tax rate of 37 percent, as opposed to the capital gains tax rate of 20 percent. In practice, this will dramatically alter if and how a seller chooses to dispose of these assets.

Before, sellers would be encouraged to sell self-made intellectual property; however, under the new scheme, sellers are less encouraged to sell these assets because they will be subjected to a significantly higher tax rate. Under the previous tax scheme, a partnership’s sale of assets could be eligible for the long-term capital gains rate. Under the new Act, entrepreneurs and individual inventors possessing newly designed, self-made technologies will not be eligible for the lower capital gains rate when they create a company from that technology or sell the technology to another who will create a company. To net the same amount of after-tax dollars following a sale, owners of self-created intellectual property must seek a higher purchase price to offset the higher tax treatment. In effect, the new tax scheme alters the pricing and value of a patent.

Congress’s intent regarding the capital gains tax is that profits and losses arising from everyday business operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

There are a few limitations to this discussion. Section 1221’s exception of intellectual property from the capital gains tax rate will likely only have a practical effect on the behavior of individuals, rather than corporations. The difference between the capital gains rate and ordinary income is much greater for individuals than it is for corporations; the corporate tax rate under H.R. 1 is 21 percent, only a one percent increase from the capital gains rate, as opposed to a 17 percent increase between the capital gains rate and the top individual income rate. Therefore, corporations are unlikely to treat the sale of these “self-created tangibles” significantly differently than under the previous tax scheme, at most seeking a modest increase in sale price to accommodate the one percent tax increase. In addition, Section 1221(b)(3) directs that musical compositions and copyrights in musical works may still be treated as capital assets. Therefore, not all intellectual property will be affected by this categorical exclusion from capital gains.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Tagged Boston University Law School, BU Law, capital gains, intellectual prpoerty, IP, IRS, Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, taxation, taxes

June 28th, 2018

in Analysis, State Legislation

Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis once called America’s states “laboratories of democracy;” state legislatures can tinker with public policy and, in theory, see what works and doesn’t work. One area where these laboratories are in full swing is in the area of state-level veteran’s benefits.

Many states provide basic benefits, in addition to benefits provided at the federal level, for veterans who serve the nation honorably and meet eligibility criteria. Things like: free admission to parks, hunting and fishing licenses at low or no cost, reduced rates for education at state funded colleges and universities, tax reductions and rebates, and veteran’s preferences for hiring in state jobs, are relatively common. Some states experiment with veteran’s policy by pushing well beyond these common state programs. Texas for example, through the very generous Hazelwood Act, provides up to 150 hours of exemption from tuition for veterans at state colleges and universities, or, if the veteran doesn’t use the benefit, for their spouse or child. Quite a few states (including Massachusetts) fund veteran’s nursing homes and are working to tackle veteran’s homelessness.

Texas State Capitol

Austin 1888

All of these programs are impressive and necessary and, they couldn’t be more important. Current veteran suicide rates are staggeringly high. More than seven thousand veterans took their lives in 2014. Of those veterans 70% were not enrolled in the federal VA system. That crisis, coupled with high veteran homelessness rates, poses significant risks to veterans living on the border of, or in, poverty. States address these challenges among their veteran populations in a variety of ways, but it is the way that Massachusetts offers commonwealth veterans in need assistance that show its progressive roots. Roots that stretch back to the Civil War.

During the Civil War, Massachusetts passed Mass. General Law Chapter 115 (Chapter 115). The statute has grown since then, but it has always provided a veteran’s agent in every Commonwealth municipality and assistance with veteran burials and grave services. Today, Chapter 115 benefits still provide a veteran’s agent (now referred to as a veterans service officer or VSO) and cemetery services, but the statute also provides a comprehensive benefit that truly seeks to serve those who have served.

This benefit is probably one of the most effective income-assistance benefits in the nation. It is funded through a city/state partnership where the city’s employee, the Veteran Service Officer (certified and trained by the state Department of Veteran’s Services), uses the regulations promulgated by the state Department of Veteran’s Services (108 Code of Massachusetts Regulation) to makes a determination about the eligibility of the veteran. Initially, if a veteran is eligible for Chapter 115, the veteran’s benefit is paid from the city’s budget. This process makes the Veteran Service Officer accountable to their respective Mayors, City Mangers, and City Councils.

The Massachusetts State House

Boston, 1787

In addition to being accountable to the municipal leadership, when a VSO approves Chapter 115 benefits auditors at the state Department of Veteran Services also reviews the veteran’s file to ensure that eligibility criteria are met and statutory guidelines and obligations are followed. If a VSO denies chapter 115 benefits, or removes a veteran from the program for failure to comply with job searches or income reporting mandates, the veteran can appeal that decision to the state Department of Veteran’s Services (and to higher administrative courts if necessary).

Throughout the veteran’s participation in the Chapter 115 program the Veteran Service Officer has statutory obligations to help the veteran file any and all VA claims and applications for healthcare and other social safety net benefits and to ensure that veterans that are able to work are actively seeking employment and reporting their income to the VSO. Commonwealth VSOs become, throughout this process, the veteran’s advocate, mentor, and coach. Finally, at the end of the fiscal year, 75% of the Chapter 115 benefits that the city pays out are reimbursed by the state Department of Veteran’s Services.

Are Chapter 115 benefits a perfect solution to all the challenges that commonwealth veterans face? Of course not. No government program, non-profit, charity, or business can address all of the complex issues that American veterans deal with. The challenges in transitioning from service in our all-volunteer military to civilian life are serious, but they are surmountable. Examples like the Hazelwood Act and Chapter 115 benefits are just two examples of how to create a net of support for veterans. Other states should look to Texas and Massachusetts to create similar programs, while continuing to experiment.

Kenneth Meador was an Army combat medic who graduated from the University of Oklahoma and Boston University School of Law (2018). He plans to focus his legal career on helping our nation's veterans.

Kenneth Meador was an Army combat medic who graduated from the University of Oklahoma and Boston University School of Law (2018). He plans to focus his legal career on helping our nation's veterans.

Tagged Boston University Law School, BU Law, Chapter 115, Hazelwood Act, Massachusetts, Texas, VA, Veterans Administration, Veterans benefits

June 18th, 2018

in Conference, News

April 22, 2018 at 5:46 pm

Last week I had the privilege of once again attending the International Conference on Legislation and Law Reform, held at the Washington College of Law at American University. I had attended last year’s conference along with several other alumni from BU’s Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic; you can read that blog entry here. This time around I had the honor of participating in the conference as a panelist!

Several old favorites returned as speakers, such as the inimitable Judy Schneider, although the conference also featured a number of new panels.

Several old favorites returned as speakers, such as the inimitable Judy Schneider, although the conference also featured a number of new panels.

Judy, a legislative expert at Congressional Research Service who co-authored the Congressional Deskbook, captivated the audience with her witty rendition of how Congress really works. Judy runs a boot camp for each new class of U.S. Representatives on congressional procedure. She shared with us the magic formula for passing bills that she gives to incoming members of Congress: You need the policy; you need the politics (though this is not to be confused with party politics); and you need the procedure. She went on to explain that most of us learned civics incorrectly—Congress was not created to pass laws, but rather “to prevent bad laws from being enacted”—then walked us through each chambers’ political and procedural hurdles in committee and on the floor.

I also really enjoyed a panel on Outside Drafters, which was new to the conference this year. The panelists were Rochelle Woodard, from the Department of Commerce, and Ronald Lampard, the Criminal Justice Task Force Director at the American Legislative Exchange Council. Both brought fascinating perspectives on drafting language for lawmakers, although neither worked within the legislative branch. Rochelle spoke of the challenges she faces as an agent of the executive branch whose job is to implement treaties and consult on export control, and discussed how she goes about balancing these responsibilities with drafting language for Congress that Legislative Counsel will inevitably review and revise. Ronald, by contrast, works for a national advocacy organization that drafts both model legislation and state-specific legislation for lawmakers. With respect to the latter, he emphasized the need for local buy-in and how he approaches collaborative drafting with stakeholders.

I had the great honor of participating in the last panel of the conference, Teaching Legislative Drafting, with my clinic professor, Sean Kealy. Professor Lou Rulli, who runs the Legislative Clinic at Penn Law, was also on the panel with one of his former students. Both professors spoke of the importance of teaching legislative drafting to law students and discussed their respective curricula. I talked about the bill that I drafted when I was a member of BU’s Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic. My client was a State Senator who asked me to draft a bill from scratch, aimed at mitigating collateral consequences to incarceration in Massachusetts. I had a great time sharing my experiences as a student in the clinic and how the skills that I learned have come in handy during my externship with the Senate HELP Committee.

I had the great honor of participating in the last panel of the conference, Teaching Legislative Drafting, with my clinic professor, Sean Kealy. Professor Lou Rulli, who runs the Legislative Clinic at Penn Law, was also on the panel with one of his former students. Both professors spoke of the importance of teaching legislative drafting to law students and discussed their respective curricula. I talked about the bill that I drafted when I was a member of BU’s Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic. My client was a State Senator who asked me to draft a bill from scratch, aimed at mitigating collateral consequences to incarceration in Massachusetts. I had a great time sharing my experiences as a student in the clinic and how the skills that I learned have come in handy during my externship with the Senate HELP Committee.

While there were far too many fabulous panels to highlight here, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the international nature of the conference. Half of the panels were dedicated to legislative issues that drafters in other jurisdictions face. I heard from drafters from Ghana, Ethiopia, China, the EU, and members of the Commonwealth Association of Legislative Counsel. They spoke on topics ranging from telecom regulations in Uganda to public participation in the legislative process in Korea to promoting drafting uniformity in Australia.

If you are interested in gaining insight into the intersection of policy, drafting, and law reform, this annual conference is not to be missed! For information about future conferences, visit http://www.ilegis.org/.

Tagged Boston University Law School, Brynn Felix, BU Law, ilegis.org, International Conference on Legislation & Law Reform, Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic, Louis Rulli, Sean Kealy

Newer

Several old favorites returned as speakers, such as the inimitable Judy Schneider, although the conference also featured a number of new panels.

Several old favorites returned as speakers, such as the inimitable Judy Schneider, although the conference also featured a number of new panels. I had the great honor of participating in the last panel of the conference, Teaching Legislative Drafting, with my clinic professor, Sean Kealy. Professor Lou Rulli, who runs the Legislative Clinic at Penn Law, was also on the panel with one of his former students. Both professors spoke of the importance of teaching legislative drafting to law students and discussed their respective curricula. I talked about the bill that I drafted when I was a member of BU’s Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic. My client was a State Senator who asked me to draft a bill from scratch, aimed at mitigating collateral consequences to incarceration in Massachusetts. I had a great time sharing my experiences as a student in the clinic and how the skills that I learned have come in handy during my externship with the Senate HELP Committee.

I had the great honor of participating in the last panel of the conference, Teaching Legislative Drafting, with my clinic professor, Sean Kealy. Professor Lou Rulli, who runs the Legislative Clinic at Penn Law, was also on the panel with one of his former students. Both professors spoke of the importance of teaching legislative drafting to law students and discussed their respective curricula. I talked about the bill that I drafted when I was a member of BU’s Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic. My client was a State Senator who asked me to draft a bill from scratch, aimed at mitigating collateral consequences to incarceration in Massachusetts. I had a great time sharing my experiences as a student in the clinic and how the skills that I learned have come in handy during my externship with the Senate HELP Committee.