Tagged: taxation

Funding the MBTA: Getting Derailed Plans Back on Track

Taking the T

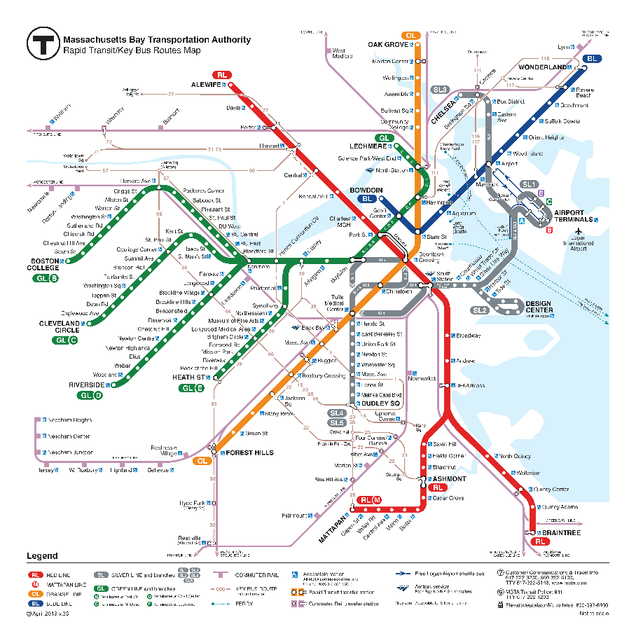

The transit system of Eastern Massachusetts, governed by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, has been the subject of much ire by residents of Greater Boston for decades, particularly where the subway, or “T,” is concerned. A prime example is last year’s decision to raise fares by 6% despite continual failures in service, such as a recent derailment on the Red Line and power shutdown on the Blue Line. As the oldest subway system in North America, many of the T’s problems stem from decades- or even century-old design decisions which are impractical to redo today. For example, its hub-and-spoke layout emphasizes access to downtown Boston at the expense of ease of travel between the edges of the system.

Broke, But Not Broken

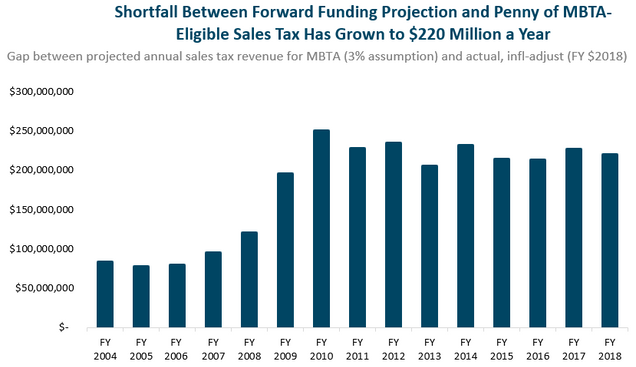

However, the primary barrier to the T being the efficient, functional transit system that Boston needs it to be is insufficient funding relative to necessary maintenance and upgrades, not to mention its current debt load. Though the MBTA system as a whole sees more than $2 billion in annual revenue, it still endures annual operating losses of more than $36 million. Significantly, the majority of its revenue does not come from operations, i.e. fares collected, but rather from sales tax and local assessment contributions. For nearly twenty years, a “penny” of all non-meal-and-drink sales tax revenue in Massachusetts has been dedicated to the MBTA budget. Because this source of tax revenue has not grown as anticipated, the MBTA budget has consequentially fallen short of expectations by well over $200 million per year. Meanwhile, costs of new projects continue to balloon. The cost of an upgraded fare collection system, originally budgeted at just over $700 million, has now grown to over $900 million.

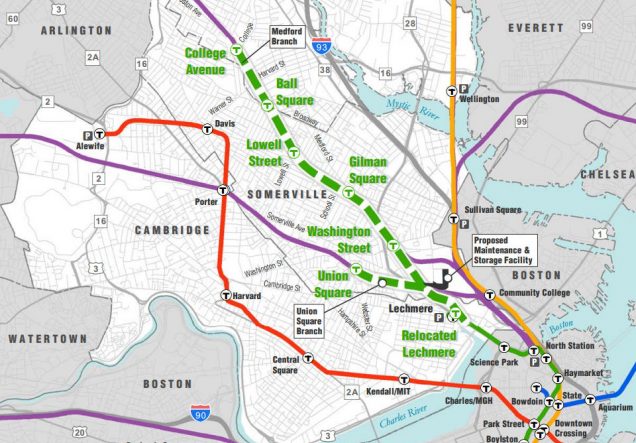

Boston City Councilor Michelle Wu argues that incremental fixes and patching of problems is insufficient; rather, we must invest in the system as a whole with a focus on expanding access. The necessity of serious capital investment became especially apparent after historic blizzards in early 2015 forced a system-wide shutdown. Wu has pointed to Governor Charlie Baker’s reluctance to act as an obstacle to the requisite overhaul the T needs. In response to pressure from her and other transit advocates, last summer Gov. Baker announced plans to accelerate an ongoing five-year, $8 billion capital investment program which kicked off in early 2019. The program aims to provide new rapid-transit buses and train cars, modernize the Red and Orange Lines, and fund a major expansion of the Green Line into underserved areas of Somerville and Medford. The latter, a long-suffering project decades in the making, is an example of the importance of major investment in transit: once complete, the percentage of Somerville residents within walking distance to light rail will increase to 80%, up from a current 20%. Gov. Baker’s acceleration includes more aggressive closures to allow for infrastructure work, more inspections and maintenance, negotiations with contractors, and the creation of a new team of MBTA personnel with the flexibility to work on multiple projects.

Capital Infusions

Even so, continued problems, such as the aforementioned Red Line derailment, prompted Gov. Baker to propose an $18 billion bond bill for transportation throughout the Commonwealth last year, providing money to the entire Massachusetts Department of Transportation, including a $5.7 billion slice for the MBTA. This bill, An Act Authorizing and Accelerating Transportation Investment, most recently received approval, with an amendment, from the House Committee on Bonding, Capital Expenditures and State Assets and moved before the House Committee on Ways and Means in late February, 2020. This Act would fund road and bridge repairs, MBTA upgrades, and the electrification of regional transit services, as well as contribute to big projects such as Cape Cod Canal bridges and the Green Line Extension. The bill also provides support for improving pavement on public roads and building small bridges as well as help for municipalities seeking to make their roads more cyclist- and pedestrian-friendly. Other provisions aim to reduce traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions by building bus lanes and working to reduce bottlenecks. Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack highlighted the importance of action on other projects which complement improved transit service to maximize the impact of the bill. Such legislation includes Gov. Baker’s proposed Housing Choices Act, which would streamline zoning approval for certain housing projects.

This past January, Gov. Baker also proposed a $135 million budget increase for the MBTA, possibly in response to a scathing December 2019 report by the Safety Review Panel which found deficiencies “in almost every area” of the MBTA system. A major criticism was the recent over-emphasis on capital improvements and not enough support for regular maintenance and safety, with staff being diverted away from the latter. However, it is unclear how exactly the infusion of funding would be spent.

It should be noted that there currently remain $743 million in outstanding senior revenue bond loans to MassDOT, though the Department maintains an A+ rating for borrowing. Though the Act Authorizing and Accelerating Transportation Investment would be funded by further borrowing via bonds, its original version allocated half of all revenue from a potential greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program with other states in the region to public transit, creating a stream of revenue as well as encouraging more fuel-efficient cars. However, that provision was stricken by the Transportation Committee, which argued that they cannot allocate funds to a program that does not yet exist. Lawmakers instead plan to increase fees on transportation network companies and deeds excise taxes.

COVID-19 Crisis

The amendments, including those made earlier by the House Committee on Transportation, include the elimination of $50 million in business tax cuts to encourage employees to work from home and thus reduce traffic congestion, a quaint decision in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic which has forced millions to work from home anyway. The MBTA has been understandably hit hard, and as of April, ridership on the T was down more than 90% from late February, with bus service down nearly 80%. Anticipated losses this year exceed $213 million due to a 95% plunge in fare collection and drops in revenue from advertising and state sales tax. MassDOT hopes to cover the loss with an expected infusion of $840 million in federal funds through the CARES Act. Meanwhile, the MBTA has reduced service, instituted cleaning and sanitizing regimes for vehicles, and has begun requiring employees and remaining riders to wear face masks.

Needless to say, major investment decisions as of this writing have been put on hold. However, once this crisis has passed, it is critical that Massachusetts act to ensure its transit services remain a functional asset to the people of the Greater Boston Area and beyond.

Kellen Safreed anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Kellen Safreed anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Making Big Tech Pay Their Share: The Taxation of Digital Advertising in Maryland

In sharp contrast to the bevy of tax incentives offered to Amazon as part of a bid for the so-called “HQ2,” Maryland has charted a path towards taxation of technology companies as part of its commitment and obligation to its residents. This move to hold large companies accountable for the money they derive from Maryland residents is laudable, given the amount of data mined from individuals and used to sell targeted digital advertising as well as the crisis of state budget shortages. However, as written, Maryland’s efforts raise serious legal concerns that jeopardize the viability of the current iteration of the bill. The bill draws on an existing model to achieve important social goals. However, in the context of the American legal framework, the current iteration of the bill raises First Amendment freedom of speech concerns and faces further challenges under the commerce clause and federal legislation enacted to promote and facilitate Internet commerce. These shortcomings need not be fatal, though. With modest redrafting, the policy underlying the bill could be implemented in order to fulfill Maryland’s goals.

The bill

Introduced in the Senate as Senate Bill 2 and in the House as House Bill 695, parallel bills in the Maryland legislature impose a

tax on gross revenues derived from digital advertising. The amount ranges from 2.5% for a corporation with annual gross revenues from $100 million to $1 billion up to 10% for those with gross revenues over $15 billion. The revenue raised will go to the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Fund, which funds K-12 education improvements in the state. This policy, though lauded as the first attempt to tax digital advertising revenues in the United States, is not without global precedent. Rather, it is modeled after a French law, which levies a 3% tax on digital interface and “targeted advertising services” in France. The tax only applies to companies with global revenues from digital interface and targeted advertising of more than €750 million globally, with at least €25 million of which was derived from French users. France enacted this legislation July 11, 2019, and was quickly rebuked by the American business community. In particular, President Trump threatened countermeasures of tariffs up to 100% on $2.4 billion worth of French imports to the United States, including sparkling wine and cheese. As a result, France and the U.S. negotiated a pause on the enactment of the law on the condition that the threatened tariffs not go into place.

Like its French model, Maryland’s bill specifically targets large technology companies. The Fiscal and Policy Note for the Maryland bill calls out by name Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Facebook, and Amazon. Proponents suggest that this legislation will force tech companies to “pay their fair share” by contributing to local tax bases rather than reaping the benefits while paying only minimal tax obligations. However, the opponents are not without their own ammunition. As part of their strategy to defeat the underlying policy, they raise legal questions regarding the current drafting and scope of the bill.

Legal considerations

Opponents argue that the selective taxation represents a content-based restriction on free speech because it selectively targets some kinds of advertising based on its communicative content. Following the recent Supreme Court case of Reed v. Town of Gilbert, which expanded the category of what is considered a content-based restriction on speech, this kind of selective taxation could be viewed as falling into the category of speech subject to strict scrutiny and therefore unlikely to survive judicial review. Even as an exercise of commercial speech, subject only to intermediate scrutiny under Central Hudson Gas & Electric v. Public Service Commission, such a tax is unlikely to be sustained. Restrictions on commercial speech must be no broader than necessary to directly further a substantial government interest. Under these circumstances, improving K-12 education is likely a substantial government interest, but the program could not be considered narrowly tailored. There are other means of raising the necessary revenue without burdening commercial speech of only large technology companies.

Maryland’s tax also raises other, non-First Amendment concerns. As written, the bill could be construed as a violation of the commerce clause of the Constitution, because it would create the possibility of double taxation of the same single economic activity if every state were to adopt a similar regime, violating the “internal consistency” test. A final source of legal concern for the policy is the Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act, or PITFA. PITFA prohibits state taxation of internet access as well as discrimination against online commerce. The taxation of digital advertising, but not traditional forms of advertising, could be seen as a discrimination against online commerce in violation of PITFA.

Maryland’s tax also raises other, non-First Amendment concerns. As written, the bill could be construed as a violation of the commerce clause of the Constitution, because it would create the possibility of double taxation of the same single economic activity if every state were to adopt a similar regime, violating the “internal consistency” test. A final source of legal concern for the policy is the Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act, or PITFA. PITFA prohibits state taxation of internet access as well as discrimination against online commerce. The taxation of digital advertising, but not traditional forms of advertising, could be seen as a discrimination against online commerce in violation of PITFA.

Looking forward

The French example and advertising industry outcry against the Maryland proposal suggest that taxation of digital advertising will be a difficult prize to win. Significant political, economic, and legal hurdles remain. However, in an era of declining state revenues and K-12 funding crises, novel solutions must be sought. The digital advertising industry, reaping incredible profits, represents a tempting source of revenue for states dealing with these demands. However, as constructed, the policy presents serious legal shortfalls. This is not to say that the taxation of a major economic activity ought to be abandoned as a policy proposal. Rather, the specific construction of the statute needs to be reconsidered as the Maryland legislature moves forward. For example, a modification in the way that “in the state” is determined for the purposes of the tax could eliminate the concern of double taxation and, therefore, the commerce clause concerns. Where modest redrafting could save the policy from its legal challenges, it seems imperative to do so given the high stakes underpinning the policy.

Jordan Neubauer anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Jordan Neubauer anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

The American Family Act is both Effective Policy and Politically Viable, Let’s Make it Law

With the 2020 Democratic Primary underway, candidates are engaged in a ‘race to the left’ defined by progressive proposals for expansive federal programs aimed to combat social, economic, and environmental injustices. Underpinning these ideas is the belief in government as an effective mechanism for improving the lives of Americans and a strong rebuke of the Republican tenants that small government, deregulation, and tax cuts are the appropriate tools to lift up the impoverished, marginalized and economically struggling.

The American Family Act of 2019 (AFA) seems to be another progressive policy with noble aims, but dim prospects for bipartisan support. Most recently introduced in March 2019 by co-sponsors Senator Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH), the AFA aims to reconfigure and expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC) to more effectively combat childhood poverty by increasing the financial support and removing the implicit work requirement. However, upon closer examination of its tax-focused policy structure and pro-family political implications, the AFA is distinct from other progressive Democratic proposals because it has the ability to transcend the traditional divisiveness surrounding social welfare legislation. Thus, if framed correctly and advocated for effectively, the AFA is an endangered species in today’s gridlocked and sharply divided Congress: a sweeping progressive policy with political viability.

Enacted in 1997, and expanded since with broad bipartisan support, the CTC is an anti-poverty measure that aims to mitigate the costs of raising children through a tax deduction of up to $2,000 per year for each eligible child. The CTC is administered primarily through a non-refundable tax credit, where a family’s income tax liability is reduced by the credit value. Families without taxable income—or whose taxes are below the credit value—are excluded from taking full advantage of the credit. The CTC partially accounts for this with a refundable option for these families. However, eligibility is still subject to a taxable earnings requirement of $2500. Furthermore, refundable credits are capped at 15% of taxable income and $1400 annually. These limitations exclude the poorest and most vulnerable children from the benefit. Roughly 27 million children under seventeen are ineligible for the full credit and many don’t qualify at all. Despite its shortcomings, the CTC functions as an effective tool for alleviating child poverty, lifting one in six previously poor children and their families out of poverty each year.

Enacted in 1997, and expanded since with broad bipartisan support, the CTC is an anti-poverty measure that aims to mitigate the costs of raising children through a tax deduction of up to $2,000 per year for each eligible child. The CTC is administered primarily through a non-refundable tax credit, where a family’s income tax liability is reduced by the credit value. Families without taxable income—or whose taxes are below the credit value—are excluded from taking full advantage of the credit. The CTC partially accounts for this with a refundable option for these families. However, eligibility is still subject to a taxable earnings requirement of $2500. Furthermore, refundable credits are capped at 15% of taxable income and $1400 annually. These limitations exclude the poorest and most vulnerable children from the benefit. Roughly 27 million children under seventeen are ineligible for the full credit and many don’t qualify at all. Despite its shortcomings, the CTC functions as an effective tool for alleviating child poverty, lifting one in six previously poor children and their families out of poverty each year.

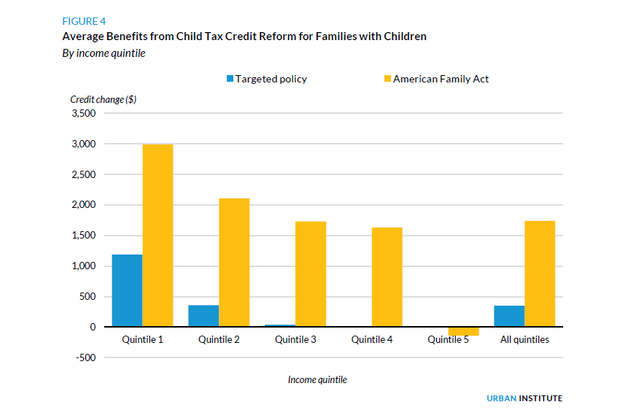

Building on the existing CTC, the AFA aims to increase its impact through five major revisions. First, it creates an expanded credit for children under six (YCTC) of $300/month ($3,600/year). Second, the AFA increases the credit for children seven though sixteen to $250/month ($3,000/year). Third, the AFA returns the upper income eligibility to pre-Trump tax levels, with phase-out beginning at $75,000 for single and $110,000 for married families. This concentrates the benefit on the poor and increasingly strapped middle-class. Fourth, and most importantly for reducing rates of childhood poverty, both credits are fully refundable, eliminating the implicit work requirement. Finally, the AFA introduces a monthly advance to “smooth families’ incomes and spending levels over the course of a year,” while preserving the fundamental structure as a refundable tax credit.

Policy analysts predict the AFA would have powerful and lasting effects on reducing childhood poverty. A report by the Columbia Population Research Center found the AFA would reduce child poverty by 38 percent, and the duel-impact of increasing the credit and eliminating the earnings requirement would move approximately 4 million children out of poverty and 1.6 million out of deep poverty. In 2015 Congress—in a bipartisan action—commissioned a group of experts to produce “a nonpartisan, evidence-based report that would provide its assessment of the most effective means for reducing child poverty by half in the next 10 years.” The report found the most impactful programs involve cash assistance to families, and noted the most effective policy for poverty reduction would be a $2,700 unrestricted child allowance, which the authors report, would alone cut child poverty by a third. Cash subsidies to low income families are also credited for increasing investment in early child development, which links to better learning outcomes and future earning potential. Thus, the AFA implements evidence-based policy for combatting child poverty and promoting broader social and economic benefits for its beneficiaries.

While much of these same benefits could be realized in other progressive policies (such as Universal Basic Income and Universal Childcare), theses government programs require strong Democratic congressional majorities. A closer examination of the political landscape surrounding tax credits and unpaid domestic labor reveals the critical ways the AFA’s form and function can attract Republican support.

To understand the bipartisan potential, we must discuss why many conservatives traditionally support the CTC. Structured fundamentally as a tax credit, the CTC can be framed as a reduction of the federal government. The CTC is more palatable than other anti-poverty initiatives because it bypasses the need for a government program with an expansive bureaucratic administration and a redistributive tax for funding. While this framework is somewhat undermined by the (partially and conditionally) refundable nature, still the CTC addresses the widely supported issue of reducing childhood poverty through an initiative that shrinks the size of the federal government by taking in less tax revenue and not offering a new administrative service. Bennet’s description of the plan demonstrates his awareness of this political tightrope. In the AFA announcement he described it as a tax cut and credit, not a benefit or allowance. When questioned on his word choice he told reporters “I think you could describe it either way.”

Republicans can also frame the CTC and the AFA expansion as pro-family. Conservatives often decry the traditional family structure is under assault and argue programs like the childcare tax credit and proposals like universal childcare structurally nudge stay-at-home parents into the workforce by discounting their unpaid domestic labor. The AFA expansion gives parity in treatment of working and stay-at-home parents. The AFA’s significant credit increase could be framed as offering a simplified and neutrally applied childcare subsidy in lieu of other universal childcare proposals, which commentators on both sides of the debate have described as disadvantaging stay-at-home parents. The Niskanen Center, a center-right think tank, supports expanding the CTC in much the same way the AFA does. It argues the increased credit should unite the left and right through its anti-poverty, pro-family message and impact. It asserts that neutral funds promote individual choice by giving parents the decision-making power to use funds to “help pay for child care for two-parent working families, or help a stay-at-home parent or a grandparent afford necessities such as diapers, transportation, access to the Internet, or educational materials for a child.” The Niskanen Center is not alone on the political right. During his campaign, Donald Trump’s Childcare Plan included a neutrally applied childcare deduction, “offering compensation for the job [stay-at-home parents are] already doing, and allowing them to choose the child care scenario that's in their best interest.” Further demonstrating the bipartisan nature of the fundamental concept and policy, Trump’s December 2017 tax plan expanded the annual CTC credit from $1000-$2000 dollars and modestly lowered the taxable income requirement.

The AFA should pass because it is good data-backed policy, but unfortunately that is not enough. It is the policy’s structure rooted in the tax code, implications supporting stay-at-home-parents, and foundation in a popular bipartisan program that give the AFA an opportunity transcend partisan gridlock and pass through congress.

Rebecca Gottesdiener anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

Rebecca Gottesdiener anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2020.

A New Exclusion from the Capital Gains Rate: Self-Created Intangibles

On December 20, 2017 Congress passed H.R. 1, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This act introduces the most sweeping tax changes in decades lowering individual and corporate tax rates, with one stated goal of allowing buyers to write off the costs of new investments. In relevant part, this Act introduces one provision that removes a favorable tax rate for innovators with self-created intellectual property and eliminates the ability to treat certain self-created intellectual property as capital assets.

Under the prior tax scheme, self-created intellectual property would have been subject to the capital gains tax rate following sale of those assets. However, Section 1221 of the Internal Revenue Code under the new law exempts self-created intellectual property from capital gains treatment.

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

Effectively, the sale of self-made intellectual property typically will now be subject to the higher top individual tax rate of 37 percent, as opposed to the capital gains tax rate of 20 percent. In practice, this will dramatically alter if and how a seller chooses to dispose of these assets.

Before, sellers would be encouraged to sell self-made intellectual property; however, under the new scheme, sellers are less encouraged to sell these assets because they will be subjected to a significantly higher tax rate. Under the previous tax scheme, a partnership’s sale of assets could be eligible for the long-term capital gains rate. Under the new Act, entrepreneurs and individual inventors possessing newly designed, self-made technologies will not be eligible for the lower capital gains rate when they create a company from that technology or sell the technology to another who will create a company. To net the same amount of after-tax dollars following a sale, owners of self-created intellectual property must seek a higher purchase price to offset the higher tax treatment. In effect, the new tax scheme alters the pricing and value of a patent.

Congress’s intent regarding the capital gains tax is that profits and losses arising from everyday business operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

There are a few limitations to this discussion. Section 1221’s exception of intellectual property from the capital gains tax rate will likely only have a practical effect on the behavior of individuals, rather than corporations. The difference between the capital gains rate and ordinary income is much greater for individuals than it is for corporations; the corporate tax rate under H.R. 1 is 21 percent, only a one percent increase from the capital gains rate, as opposed to a 17 percent increase between the capital gains rate and the top individual income rate. Therefore, corporations are unlikely to treat the sale of these “self-created tangibles” significantly differently than under the previous tax scheme, at most seeking a modest increase in sale price to accommodate the one percent tax increase. In addition, Section 1221(b)(3) directs that musical compositions and copyrights in musical works may still be treated as capital assets. Therefore, not all intellectual property will be affected by this categorical exclusion from capital gains.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.