Category: Analysis

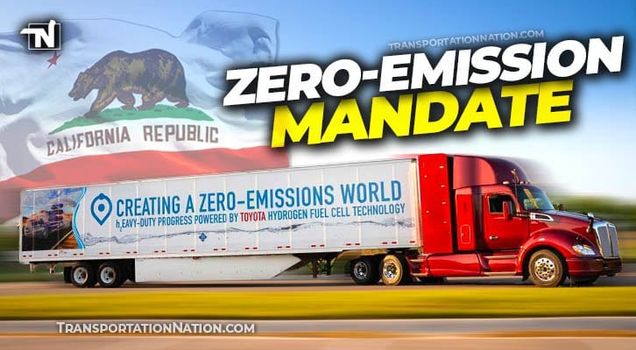

Fighting the Federal Government: California’s Mission to Stop Environmental Rollbacks

In July of 2020, California passed the historic Clean Trucking Rule, the first of its kind in the world. The rule requires manufacturers to sell increasing percentages of zero-emission trucks in the state. While many have applauded the action, the Trump administration was not a fan of the rule. California and the Trump administration have been at odds for years, as California has attempted to make up for the lack of climate action at the federal level. Over just four years, President Trump’s administration reversed over 100 environmental rules and regulations. To make up for the loss, California has passed numerous regulations and initiated at least twenty-four lawsuits to halt the Environmental Protection Agency’s (“EPA”) rollbacks. California, given its unique legal status on environmental issues, has proven itself to be a clear leader on climate action and emission reduction.

The Clean Air Act

When it comes to the climate, California is not restricted by Constitutional provisions such as the Commerce and Preemption Causes. The Clean Air Act (“CAA”), first passed in 1970, gives the federal government the ability to regulate pollutants that are emitted into the ambient air and prohibits states from adopting or attempting to enforce any of their own motor vehicle emission controls. However, section 209(b) of the CAA allows states that had adopted standards prior to 1966 could apply for a waiver to that prohibition; and only California qualified. California was the first state to attempt controlling auto pollution and needed the ability to adopt more stringent controls to address the state’s extreme smog problem. To set new motor vehicle emissions standards, California must apply for a waiver from the EPA. The EPA administrator shall grant the waiver unless the standard is (1) arbitrary and capricious, (2)is not needed for compelling and extraordinary conditions, or (3) is not consistent with the CAA. Since 1970, administrators have consistently granted California its waivers. One exception was a waiver for new emissions restrictions on vehicles starting in 2009 that was initially denied in 2008, but President Obama later reversed the denial. This waiver program has created numerous California programs that differ from federal standards, including the Zero Emissions Vehicles (“ZEV”) Program, The Advanced Clean Cars program, and Low Emission Vehicles (“LEV”) Standards.

Under section 177 of the CAA, other states can choose to adopt either the current federal regulations or the California regulations if that will help the state achieve the CAA requirements more efficiently. As of August 2019, fourteen states have adopted portions of California’s ZEV and LEV programs.

California’s New Rule

The California Air Resources Board (“CARB”) established the Advanced Clean Truck Program. The program requires that

beginning in 2024 manufacturers sell zero-emission trucks— that is electric and fuel cell powered trucks—as an increasing percentage of their annual California sales. Zero emission trucks need to make up 55% of Class 2b – 3 truck sales, 75% of class 4 – 8 straight truck sales, and 40% of truck tractor sales by 2035. Massachusetts and seven other states have pledged to follow California’s lead for medium and heavy duty trucks. Additionally, fifteen states and Washington D.C. have signed a memorandum of understanding pledging to each develop an action plan to support widespread electrification of medium and heavy duty vehicles.

With these monumental steps forward, the federal government started to push back. The Trump EPA and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (“NHTSA”) issued a final rule titled the “One National Rule Program,” which finalized parts of the Safer, Affordable, Fuel-Efficient (“SAFE”) Vehicles Rule that was first proposed in August 2018. The action makes clear that federal law preempts state and local tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions standards as well as ZEV mandates. As soon as President Biden took office, however, he ordered federal agencies to reexamine these changes.

The EPA and California’s Rule

The California rule is set to take effect in 2024, but a waiver must be approved by the EPA beforehand. The EPA has never gone through a denial of a California waiver before, but that has not stopped the Trump Administration from trying to revoke previously granted waivers for zero emission passenger vehicle standards. The EPA is pursuing the revocation of California’s 2013 preemption waiver for greenhouse gas emissions and ZEV programs. This revocation is currently being challenged in court. If former President Trump won the 2020 election, the EPA may have tried to deny California’s zero emission truck regulations waiver. The EPA, however, would have faced an uphill battle because there is clear evidence that reducing emissions is necessary to help California achieve its CAA goals. California’s argument would have been bolstered by the recent wildfires that destroyed large swaths of the state. It was unlikely the EPA could have offered enough solid evidence to uphold their waiver denial. In addition, most legal experts agree that California, and the states that follow their regulations, had a strong case that the Trump Administration’s efforts were unlawful. Still, the changing balance on federal appeals courts and the Supreme Court could undermine California’s waiver process and spell the demise of the original purpose and intent of the CAA. For the time being, however, California and allied states continue to have a valuable tool to fight climate change and reduce emissions across the entire nation regardless of who controls the EPA.

The California rule is set to take effect in 2024, but a waiver must be approved by the EPA beforehand. The EPA has never gone through a denial of a California waiver before, but that has not stopped the Trump Administration from trying to revoke previously granted waivers for zero emission passenger vehicle standards. The EPA is pursuing the revocation of California’s 2013 preemption waiver for greenhouse gas emissions and ZEV programs. This revocation is currently being challenged in court. If former President Trump won the 2020 election, the EPA may have tried to deny California’s zero emission truck regulations waiver. The EPA, however, would have faced an uphill battle because there is clear evidence that reducing emissions is necessary to help California achieve its CAA goals. California’s argument would have been bolstered by the recent wildfires that destroyed large swaths of the state. It was unlikely the EPA could have offered enough solid evidence to uphold their waiver denial. In addition, most legal experts agree that California, and the states that follow their regulations, had a strong case that the Trump Administration’s efforts were unlawful. Still, the changing balance on federal appeals courts and the Supreme Court could undermine California’s waiver process and spell the demise of the original purpose and intent of the CAA. For the time being, however, California and allied states continue to have a valuable tool to fight climate change and reduce emissions across the entire nation regardless of who controls the EPA.

Conner Kingsley anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Conner Kingsley anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

A More Perfect Election: Which COVID Election Reforms Massachusetts Should Keep And What Needs To Be Fixed

While the COVID-19 pandemic will no doubt be remembered as one of our nation’s most tragic events there may be at least one bright spot that emerges from an otherwise catastrophic era: a ground up rethinking of elections systems. It’s was not ideal timing; many voters believed that the 2020 general election was the most important in a generation and also feared that mass voting system reform would wreak havoc. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 election experience offers the opportunity to create needed and lasting improvements to our electoral system.

The Massachusetts Legislature prepared for the pandemic election by passing “An Act Relative to Voting Options in Response to Covid-19” a few months before the September 1, 2020 primary. The Act provided for early voting before the primary and greatly  expanded access to mail-in voting for both the primary and general election. Most of the Act’s provisions expired on December 31, 2020, but this may be for the best; the Legislature should develop a more permanent election reform bill during the new legislative session. Below are provisions lawmakers should keep—and scrap.

expanded access to mail-in voting for both the primary and general election. Most of the Act’s provisions expired on December 31, 2020, but this may be for the best; the Legislature should develop a more permanent election reform bill during the new legislative session. Below are provisions lawmakers should keep—and scrap.

KEEP: No-excuse vote-by-mail option for both primary and general elections.

Current Massachusetts law allows no-excuse mail-in voting only for biennial general elections. In other elections a voter must be either absent from their municipality or physically disabled to qualify for mail-in voting. The recent act allowing mail-in voting for the primary should become the norm. Of the estimated 18.9 million registered voters who did not cast a ballot in 2016, 19.3% percent cited reasons (see table 4) such as transportation problems, busy schedules, inconvenient polling places—and another 3% simply forgot. When Colorado implemented all-mail voting in 2014, election turnout increased 9.4% overall. The biggest gains were with traditionally low turnout groups: younger voters (16.6% increase), blue-collar workers (10%), and minority voters (13.2% for Black voters, 10% for Latinx voters, and 11.2% for Asian voters). Utah and other states increasing vote-by-mail saw similar increases in turnout. This year, 1,705,388 voters participated in the Massachusetts primary; the highest raw vote count ever for a primary. Granted, there was great voter enthusiasm due to contentious US Senate race between Senator Ed Markey and Congressman Joe Kennedy, but a lot of credit should go to the COVID-19 election reforms since about half of the ballots were sent by mail. In a state where non-Presidential Primary elections have peaked around 26% in the last 30 years, there’s no doubt that mail-in balloting is the way to keep this number rising in future.

SCRAP: Mail-in Ballot Applications.

Currently, Massachusetts requires voters to fill out and return an application to receive their mail-in ballots. Legislators should scrap this unnecessary and costly hurdle and join 10 other states that mail ballots to all registered voters.

First, the application requirement costs the Commonwealth a lot of money. Undoubtedly, the state made the right move by mailing applications to every voter—but paid postage for at least 4.6 million pieces of mail one-way, and millions more that were returned. There is also the cost of labor to prepare the mailings and process the returned applications. Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin estimated that each of the two mailings cost around $5 million.

Secondly, mail-in ballot applications are a superfluous hurdle to casting a vote in a primarily mail-in election regime. To a voting populace that already has difficulty meeting registration deadlines or remembering election day, an application requirement presents yet another step to forget and a deadline that can easily be missed. Mailing ballots directly to voters eliminates this unnecessary barrier to entry and ensures that every voter receives a ballot in a timely manner, no hoop-jumping required.

KEEP: Ballot Drop Boxes.

The July bill added the option of returning mail-in ballots “via a secured municipal drop box.” This was a huge win for both busy voters who are skeptical of the USPS and for the Commonwealth, which saves money on the return postage. This is a long-term change reflected in the written statutes and should be a positive change in all future elections!

SCRAP: Election Day Deadline for Receiving Ballots.

Current Massachusetts law only allows counting late ballots if they come from overseas. In the COVID Act, the legislature adopted a 3-day extension for ballots postmarked by election day for the November general election, but not the primary election. This distinction lead to an unsuccessful legal challenge by a candidate in the Democratic race for the Fourth Congressional District. 8,000 ballots were later rejected for arriving past the deadline. Given the recent problems with the USPS, the election day receipt deadline simply won’t cut it.

The 3-day window was a good starting point, but it is falls woefully short of the laws in other states. In 2020, 24 states have receipt deadlines of at least 5 days, and of those, 14 states allow ballots to be counted even beyond 5 days. It’s difficult to pinpoint the appropriate amount of time needed here in the Bay State without more data, but there’s no reason that progressive Massachusetts should have anything shorter than a 5-day late ballot allowance.

BONUS: Add extended cure period for defective mail-in ballots.

It’s unavoidable that a certain amount of ballots will be returned unsigned or in the wrong envelope. In September, at least 3,000 ballots were discarded because of a defect. Although Massachusetts is one of 18 states with a “cure provision” that allows voters to fix the defect with their mail-in ballot, there is room for improvement. In 2020, when the clerk received a defective mail-in ballot, the official must mail the voter a form explaining that their ballot was rejected and a substitute ballot, but only if “there is clearly []sufficient time for the voter to return another ballot.” (950 C.M.R. § 47.10(5)(b)).

Massachusetts should make two important changes to ensure every voter has their ballot counted. First, change the methods of notification. Massachusetts should copy Hawaii and Rhode Island and allow election officers to notify voters of a defective ballot by first-class mail, telephone and email. Second, allow voters to cure their ballot past election day. Other states offer anywhere from 2 to 14 days for voters to fix any defects in their ballots. These measures should help to close that final gap between ballots cast and votes counted.

There are positive signs that Massachusetts could be moving towards a primarily mail-in election future. Hopefully, the legislature will mitigate the pitfalls from this year’s attempt and incorporate successful policies used by other states to ensure that all voters have a meaningful opportunity to participate.

Emily Swanson anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Emily Swanson anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

There’s No Such Thing as Sex Without Consent

On January 16, 2020, the Massachusetts Senate passed S.2475 “An Act Relative to Healthy Youth,” which creates mandatory guidelines schools must follow when implementing their sex education curricula. This does not require schools to adopt a curriculum, and there is an opt-out provision for parents who do not wish their children to receive this education. Still, the bill requires medically accurate information be shared, that a comprehensive view of sex education be taught that goes beyond abstinence-only education, and, perhaps most importantly, the bill requires schools teach students about consent, boundaries, and healthy and safe relationships. Unfortunately, the 2020 legislative session came to an end with the bill stuck in the House Committee on Ways and Means.

Sex Education in the United States

In the United States, sex education started as a movement to discourage masturbation in young men, and encourage abstinence before marriage. While sex education started to spring up more in public schools during the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s when the the American Medical Association and public health officials first advocated a standardized curriculum. The 1960s saw religious and conservative groups attack sex education, asserting that teaching youths about sex would make sexual engagement more likely. In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS health crisis led many officials, backed by federal funding, to require abstinence-only sex education in schools.

before marriage. While sex education started to spring up more in public schools during the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s when the the American Medical Association and public health officials first advocated a standardized curriculum. The 1960s saw religious and conservative groups attack sex education, asserting that teaching youths about sex would make sexual engagement more likely. In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS health crisis led many officials, backed by federal funding, to require abstinence-only sex education in schools.

By 2009, the federal government was putting $170 million per year into these George H.W. Bush era programs. Under President Obama, the federal government continued funding abstinence-only programs, but also introduced a more comprehensive sex-education approach in an effort to reduce teen pregnancy. The Trump administration then gutted the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, restricting federal funding to abstinence-only programs.

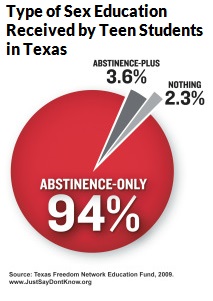

On the state level, 37 states require sex education programs to cover abstinence and 27 of those require prioritizing abstinence.  Students who attend schools with less funding are more likely to receive abstinence-only education, leading to a correlation between socioeconomic status and an increase in teen pregnancy, STDs, and sexual violence.

Students who attend schools with less funding are more likely to receive abstinence-only education, leading to a correlation between socioeconomic status and an increase in teen pregnancy, STDs, and sexual violence.

Currently, only 8 states and Washington D.C. require students learn about consent. Of these, seven passed their requirements within the last four years. In just 2019, four jurisdictions passed consent education requirements and nine more states introduced similar legislation.

The Importance of Consent Education

Sex is not sex without consent – it’s rape.

A Columbia University study indicated that those who received training in how to refuse sexual advances were less likely to be sexually assaulted in college. There was no similar correlation between abstinence-only sex education and sexual assault. Equipping students with the ability to set their own boundaries is important, but teaching students to recognize and respect those boundaries in others is just as necessary to prevent sexual violence. Merely giving students the tools to help them potentially get out of a situation they don’t want to be in is not enough, because it does not express the importance of consent in sexual interactions. As long as people fail to recognize and respect the consent of others, there will always be uncomfortable or dangerous situations to try to get out of – it’s mopping up the water from the overflowing sink without turning off the tap.

For young children, consent education reassures them that they have a say in what happens to their bodies (something many children are not aware of), and it teaches them to respect other peoples’ choices, as well. As students age, understanding consent as a concept allows them to form fundamental understandings of what healthy relationships with others look like. Beyond a reduction in sexual violence and misconduct, these are important life-skills that reach far beyond sexual situations.

The Opposition

There is still support for abstinence-only sex education in many parts of the country, and consent education is often seen as condoning sex. Unfortunately, resisting consent education works against abstinence-only goals by not providing students with the tools needed to establish healthy boundaries and respect for each other’s physical space. These skills are key for both those who wish to remain abstinent until marriage and for those who engaging in sex.

condoning sex. Unfortunately, resisting consent education works against abstinence-only goals by not providing students with the tools needed to establish healthy boundaries and respect for each other’s physical space. These skills are key for both those who wish to remain abstinent until marriage and for those who engaging in sex.

Some of those who oppose consent education, especially for younger students, worry that the subject matter may be too mature, but consent education does not have to be presented along with sex education for younger students to be effective. Consent is ultimately about permission, which is a concept children can easily grasp. For example, sharing and borrowing things involves consent. Additionally, teaching consent around hugging is a way to instill physical boundaries in children.

Looking Forward

West Virginia, Rhode Island, and D.C. have all adopted comprehensive legislation on consent education. These states require consent education based on the student’s age, introduce the concept of consent to younger children while assuaging some of the opponent’s concerns.

Harvard’s Graduate School of Education created a consent education model based on suggestions from educators across the country. The model proposed laying a foundation of consent and boundary building behaviors in younger children, and then including sex in the conversation for older students.

The Harvard model also recognizes that consent education should not be limited to straight boys but that anyone can perpetrate sexual violence and misconduct. Just as socioeconomic factors play a role in who receives comprehensive sex education, individuals holding certain identities are disparately impacted by sexual violence and students need to be aware of these inequities as they learn to navigate sex and consent.

Every school should adopt some form of consent education both before and during sex education. Otherwise, we will continue to endure a society that fails to respect the boundaries and choices of others. The Massachusetts Senate passed bill was a step in the right direction. Hopefully, the bill will become law during this new legislative session.

Alexa Weyrick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Alexa Weyrick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Real Cost of COVID-19: The Fractured Health Care System

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has uprooted the very foundation everyday life, turning socialization into a moral evil, and weaponizing safety precautions as political propaganda. These clear immediate costs, amounting in the loss of life, jobs, and social pleasures, are merely the surface to a rather elaborate system of institutional market failures that are bound to follow. While the coronavirus promptly began a long-awaited economic recession, forcing more than 31 million people in the United States to file for unemployment insurance, there has been a catastrophic loss of employer based health insurance coverage for many individuals, leaving only those who are eligible and qualified to move over to Medicaid or other subsidized health insurance policies. Unfortunately many have found themselves stuck in what is known as the “coverage gap,” with health care access becoming a novelty when its demand is at an all-time high.

Hospital and Insurance Coverage Crisis

Hospitals are largely believed to be price inelastic institutions, where demand for health services will remain constant, and funds will continuously keep providers operational even during economic recessions. While one might think that the COVID-19 public

health crisis would drive health care consumption, benefiting hospitals, it has actually been quite the opposite. Demand for healthcare services has been primarily for expensive specialized care, imposing high out-of-pocket expenses on individuals who are treated for COVID-19, and has further shifted from routine visits, seeing reductions as high as 60%.. The increased costs in specialized care, combined with the decrease in less costly routine care has not been the only shock to the health care industry. Additionally, by April of 2020, 1.4 million health care jobs were lost to enable hospitals to produce positive profit margins, creating staffing shortages across many US hospitals. This, paired with over 40 million Americans losing their jobs and shifting to subsidized healthcare and Medicaid, has created a loss of up to 20% of the commercial insurance market. By decreasing those covered by commercial insurance plans, cost aversion behaviors will decline health care usage, and those who are eligible will move over to Medicaid. Shifting from private to public insurance at this rate will cost Hospitals $95 billion in annual revenue. While Hospitals are experiencing adverse pressure, threatening what was believed to be recession proof industry, it is merely one of the many cracks that make up an unsustainable health care system.

The CARES Act and FFCRA’s Truncated Effect on the Health Care Crisis.

The passage of both the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”) and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (“FFCRA”) has provided economic stimulus and safety protocols to expand health care access. These measures have covered COVID-19 diagnostic testing, mandating the elimination of cost-sharing, such as co-payments, deductibles, and coinsurance, for a wide array of group health plans and insurances. While this improves accessibility to preventative measures, it leaves open a large regulatory gap for the actual treatment of COVID-19, where individuals are still vulnerable to out-of-pocket expenses until they reach their cap for insurance to kick in, “ exceeding “$8,000 for an individual and $16,000 for a family.” The benefit of expanding access to testing is immeasurable, but the high costs of treatment poses a significant risk to those who are already underinsured. Further, these acts fail to eliminate cost-sharing for the uninsured, which accounts for 27.9 million nonelderly individuals in the US in 2018. While the number of uninsured Americans is certainly alarming, it is a great improvement from the number of uninsured prior to the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), where over 46.5 million nonelderly individuals were uninsured in 2010. Yet, the many positive effects that have followed the enactment of the ACA are at risk of being undone, with the Supreme Court of the United States reviewing four legal questions pertaining to the ACA.

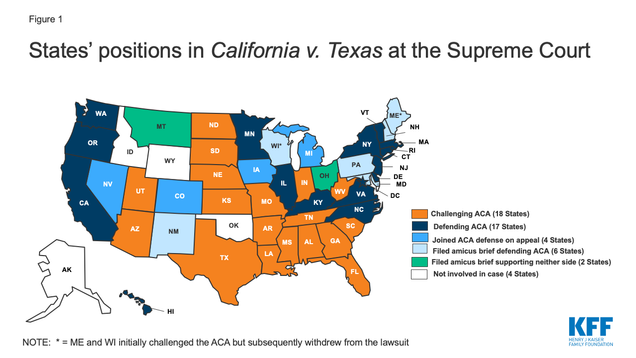

The Uncertainty of Health Care in the face of California v. Texas.

California v. Texas will be a test to the legislative muster of the ACA. With the recent confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, concerns of the ACA being overruled have surfaced as Justice Barrett has claimed that Chief Justice Roberts has “pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute.” The fate of the ACA hinders on whether the individual mandate is unconstitutional, and if so, if the individual mandate of the ACA is severable from the rest of the legislation. If the court does decide to overrule the ACA in its entirety, we may see more than 20 million individuals lose health care insurance, exacerbating the already grim public health crisis brought on by COVID-19, impacting our most vulnerable communities who struggle to gain access to health care.

California v. Texas will be a test to the legislative muster of the ACA. With the recent confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, concerns of the ACA being overruled have surfaced as Justice Barrett has claimed that Chief Justice Roberts has “pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute.” The fate of the ACA hinders on whether the individual mandate is unconstitutional, and if so, if the individual mandate of the ACA is severable from the rest of the legislation. If the court does decide to overrule the ACA in its entirety, we may see more than 20 million individuals lose health care insurance, exacerbating the already grim public health crisis brought on by COVID-19, impacting our most vulnerable communities who struggle to gain access to health care.

Disparities on Minority Care and COVID-19 Infection.

Racial and ethnic minority groups face the greatest barriers to health care access, and, in turn are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts. While the ACA had greatly reduced the proportion of racial and ethnic minorities who lack health insurance, there are numerous systemic and social hurdles that have left these minority groups uninsured at higher rates than white individuals. As a consequence, racial and minority groups have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, with racial minorities being over 2.6 times as likely to contract COVID-19, with rate of hospitalization for African American individuals being 4.7 times more than that of white individuals. Not only this, but the mortality rate is 2.1 times that of white people in the US, showing clear disparity in treatment outcomes and access to treatment.

The disproportioned access to health care services from racial and ethnic minority groups, has undoubtedly put these individuals at higher risk to unexpected out-of-pocket expenses, surprise bills, and physical harm from COVID-19. COVID-19 has shed light on the systemic racism in our health care system, unfortunately adding to the already disastrous public health crisis. The many cracks that are forming throughout our health care system will have untold effects on minority populations, and needs to be addressed through comprehensive legislative health care reform that is aimed at providing universal insurance coverage and eliminating implicit biases that contribute to lower standard care.

While the sprawling costs of COVID-19 stand out as clear reminders that we are living anything but a normal life, the true long term costs on minority populations, health care institutions, and health care access is now even more clear as Americans face another wave of COVID-19 outbreaks during these colder months. This cocktail of failures will greatly impact an already fragmented health care system, leaving our most vulnerable communities without proper health care access. Congress and the state legislatures need to secure funding for the providers of our health care services, while also increasing access to health care insurance and treatment for all individuals to minimize the long-term costs associated with COVID-19.

Kyle Hafkey anticipates graduating from Boston University Schoo of Law in May 2022.

Kyle Hafkey anticipates graduating from Boston University Schoo of Law in May 2022.

Massachusetts Criminalizes Female Genital Mutilation

“One of the most powerful things we can do to create a better Commonwealth and a better world is protect the health and safety of, and empower, women and girls.”

Massachusetts Senate President Karen E. Spilka (D-Ashland)

A win for the health, safety, and empowerment of women and girls, the Massachusetts Legislature criminalized female Genital mutilation. The Legislature, however, has more work to do in this area.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia -- or other female genital organs -- for non-medical reasons. 200 million women and girls alive today worldwide have been subject to the practice despite proof that it has no health benefits. On the contrary, FGM is known to cause a number of medical issues including severe bleeding, psychological trauma, problems with urination, cysts, infections, complications during childbirth, and increased risks of newborn deaths. FGM cases are thought to be mostly concentrated in countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. But, this does not mean American women and girls are not at risk: FGM is a cultural phenomenon, not a geographical one.

Mariya Taher -- a Cambridge, Massachusetts resident -- grew up in a Dawoodi Bohra community, a religious denomination within the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam. Growing up, she was told FGM was a sensitive topic -- one only women could discuss. She thought it was normal, and knew she was not supposed to mention it outside of her community. Mariya underwent a proceedure called khatna at age seven.

In high school, Mariya connected the dots and realized that khatna was FGM. She soon came to the sad and shocking realization that her endeared religious and cultural practice perpetrated violence against her and other women and girls in her community. FGM is strongly condemned by most Muslim communities, but members of the insular Dawoodi Bohra community revere female genital cutting as a religious obligation to remove “forbidden flesh” from young girls.

Another woman, who asked that her full name not be revealed, told a similar story. “Jennifer” is a Kentucky resident from a minority Christian community. Her parents forced her to undergo FGM at age 5. Jennifer was told she was never allowed to talk about what happened to her. Still, after many years of enduring pain in secrecy, she went public with her story at age 40. This prompted anti-FGM campaigners to investigate the secretive practice in conservative evangelical communities and minority Jewish communities.

The testimonies of survivors like Mariya and “Jennifer” helped spark important discourse around FGM and propel legislation forward.

FGM is recognized by the federal government as a form of child abuse, and internationally as a human rights violation, torture, and violence against women and girls. With the passage of the federal ban in 1966, the Female Genital Mutilation Act, performing FGM on anyone under age 18 became a felony in the United States. However, in 2018, US federal district judge Bernard A. Friedman in Michigan ruled that the federal government did not have the authority to enact legislation outside the commerce clause and held the act unconstitutional. As part of the ruling, Judge Friedman also ordered that charges be dropped against 8 people who had performed FGM on 9 girls. Some considered the ruling a blow to girls at risk, and feared that the 23 states that did not have anti-FGM laws would become “destination states” for FGM.

FGM is recognized by the federal government as a form of child abuse, and internationally as a human rights violation, torture, and violence against women and girls. With the passage of the federal ban in 1966, the Female Genital Mutilation Act, performing FGM on anyone under age 18 became a felony in the United States. However, in 2018, US federal district judge Bernard A. Friedman in Michigan ruled that the federal government did not have the authority to enact legislation outside the commerce clause and held the act unconstitutional. As part of the ruling, Judge Friedman also ordered that charges be dropped against 8 people who had performed FGM on 9 girls. Some considered the ruling a blow to girls at risk, and feared that the 23 states that did not have anti-FGM laws would become “destination states” for FGM.

Almost two years later, on August 6th, 2020, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed Bill H4606 "An Act Relative to the Penalties for the crime of Female Genital Mutilation" into law. The Massachusetts State Senate unanimously passed the legislation, which officially criminalizes the practice of FGM in Massachusetts. Under the new law, any person who knowingly commits FGM on a minor — or transports the minor within or outside the state for these purposes — will face up to five years in state prison, or a fine of up to $10,000. Additionally, the law specifies that the public health commissioner must work with the government and non-governmental organizations to set up an educational FGM prevention program, protect and assist victims, and create recommendations for training health care providers on how to recognize risk factors of FGM.

Massachusetts joined 24 other states with anti-FGM laws. The laws vary from state to state. In Arizona the punishment for FGM against a minor is imprisonment for 5.25 - 35 years and a fine of not less than $25,000. A person who performs FGM in Kansas will be imprisoned for 89-100 months, or 7-8 years. In Louisiana, the punishment is imprisonment for up to 15 years, while in Maryland, the punishment is imprisonment for up to 5 years and/or a fine up to $5,000. In Texas, an offender could face imprisonment for 6 months to 2 years and/or a fine up to $10,000.

Most state anti-FGM laws, including Massachusetts’ law, only apply to minors (including only those under age 16 in Colorado, and under age 17 in Missouri). The only states that prosecute offenders for performing FGM of women above the age of 18 are Illinois, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Tennessee.

Massachusetts’ law is a step in the right direction, but leaves room for further action.

The law recognizes FGM as child abuse and gender-based violence, while recognizing the importance of education and prevention. It also strikes a delicate balance between the law, morality, and culture, without addressing that balance in the bill. It is important to note that although one major justification for the practice of FGM is religious duty, FGM is really a cultural practice. Though practiced by Christians, Jews, Muslims, and indigenous religions around the world, none of these religions require the practice, and have instead condemned it. Still, communities that practice FGM hope to preserve their customs and cultural identity by continuing the practice. At the same time, Massachusetts seeks to protect vulnerable populations -- specifically young girls -- from the practice and punish the perpetrators.

The cultural attitudes that enforce FGM will not simply disappear because the practice has been outlawed. The Massachusetts law does not address other ways to end an unethical cultural practice such as this one. The ceremonies that accompany FGM often serve as a rite-of-passage for girls and women, and is often ritualized. FGM’s ceremonious and communal nature contribute to the difficulties associated in eradicating it. In some cultures, those performing FGM are primarily women, and are usually traditional birth attendants who inherited the role through family and revere the honor of bearing that role. Of course, Massachusetts should prioritize protecting victims and holding abusers accountable. Still, the lack of acknowledgment of the cultural differences between the lawmakers and those who practice FGM, and the lack of outreach to those communities sparks a question about whether the law will be successful in eradicating FGM in Massachusetts.

Lastly, the scope of Anti-FGM laws all over the country needs to be expanded to protect both women and girls. These laws, as they are now, leave women vulnerable to abuse since they undergo FGM as well. Laws protecting minors and not adults reflect the perception that FGM is a child abuse issue, not a women’s health issue. In reality, it is both. Some cultures perform FGM weeks after birth; some, from ages 1 to 4; others, from ages 12-15; and others, on adult women before marriage or before the birth of a first child. We know that FGM has no basis in medical practice, no benefits, and can lead to a life of pain (both physical and psychological). Female genital mutilation is a method of abuse used to control the anatomy of women and girls. Laws across the 50 states should reflect this in a culturally competent manner that focuses on prevention, education, and both physical and psychological support for victims.

Hopefully, Massachusetts and the other 49 states can pass more comprehensive laws to offer greater protections in the near future.

Temi Omilabu anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Temi Omilabu anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

What Never Was: The Indigenous American Cultural Heritage Repatriation Problem

The unfortunate beginnings of the fetishization of Indigenous American cultural heritage occurred concurrently with the systematic disenfranchisement of Native Americans throughout the United States. These events led to the amassing of millions of Indigenous American cultural heritage objects in federal repositories, museums, and private collections by the early twentieth century. Concurrently, archaeologists and anthropologists, largely funded by public research institutions like museums and universities, thoroughly destroyed prehistoric and historic sites in the hunt of the next ancient relic. The culmination of these events as well as forced assimilation created the idea that Indigenous Americans vanished and further justified the amassing of their cultural heritage. Unfortunately, today’s global society still believes in the vanishing Indian.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (“NAGPRA”) was supposed to protect the heritage of the Indigenous Americans, but it is deeply flawed and needs to be either amended or replaced.

CONGRESS’S RUSHED RESPONSE TO CONTROVERSY

The Supreme Court ruled in Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protection Association that the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (“AIRFA”), 42 U.S.C. § 1996, merely reiterates the First Amendment. Thus, the U.S. Forest Service (“USFS”) continued with road construction after minimizing the immediate impacts to the Yurok’s, Karok’s, and Tolowa’s religious practices. After the decision, the Indigenous American community knew they needed heightened protections, and the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs concluded that federal legislation was necessary. On the heels of the committee findings, federal legislation was drafted and enacted. NAGPRA was supposed to positively affect the acquisition and repatriation of Indigenous American ancestral remains and cultural heritage.

Congress enacted NAGPRA to protect Indigenous American graves and repatriate remains, providing for proper tribal burials and religious rites. Although the legislative history suggests good intentions, the federal legislation provides a façade for museums, galleries, and collectors to continue acquiring and exhibiting Indigenous American cultural heritage. NAGPRA, enacted in November of 1990 and effective a year later, requires federal agencies and institutions benefiting from federal funding that have “possession or control over holdings or collections of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects [to] compile an inventory of such items and, to the extent possible based on information possessed by [the agencies and institutions, to] identify the geographical and cultural affiliation of such items.” From here, institutions and federal agencies inventory their collections “in consultation with tribal government [officials]. . . and traditional religious leaders” and supply records for better determining “the geographical origin, cultural affiliation, and basic facts surrounding [the] acquisition and accession of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects . . . .” “If a ‘cultural affiliation of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects’ is established with a particular tribe, then ‘upon the request of a known lineal descendant of the Native American or of the tribe[,]’ the museum must ‘expeditiously return such remains and associated funerary objects.’”

WHY NAGPRA FAILS

NAGPRA is but one illustrious example of the federal government fostering conflict between Indigenous American religion and Eurocentric ideals of science. While religion and science both concern themselves with “the human identity and defining our place in the universe,” their methods employed to achieve these goals often conflict. Science utilizes deductive methodology emphasizing quantifiable information and discernible facts and leads to evidence-based conclusions. Region supports discovery through “faith, complex belief systems, and longstanding traditions supported by cultural awareness.” The answer is not and never has been one practice over the other, and America’s past placed Congress in an important decision-making role to efficiently incorporate both viewpoints. What Congress enacted is neither effective nor efficient legislation, but an all show, no substance process.

NAGPRA leans heavily in favor of Eurocentric ideals of science over Indigenous American religious freedoms and oral history. Nevertheless, Congress failed at greatly considering the issue’s greatest stakeholder—Indigenous Americans. While Congress heard the religious perspective from tribal government representatives, lineal descendants, and various other support groups, the followed in-practice NAGPRA guidelines suggest their perspective fell on deaf ears.

Indigenous Americans view funerary, sacred, and cultural patrimony objects as the extensions of once-living ancestors, and therefore deserving of the same protections afforded to ancestral remains. Treating these objects as anything less offends Indigenous American cultural practices, and disturbances “force the spirits of those individuals to wander without rest.” The scientific viewpoint sees historical and scientific value in ancestral remains and their associated objects. Bioanthropologists premise their work around these objects and remains, hoping to learn more about past and present populations as well as information about the individual ancestral remains. Bioanthropologists swayed Congress with their wishes to retain ancestral remains for future study, supporting their argument by suggesting future technologies might provide unknown answers. Of course, Indigenous Americans’ oral histories provide the answers, but the judiciary and bioanthropologists brushed those claims aside. Thus, scientists and Indigenous Americans remain on polar extremes—“either believing in continued possession for research purposes or insisting on immediate burial without study.” Congress enacted NAGPRA with a focus on the repatriation of ancestral remains and associated objects. Yet, the rushed and sloppy NAGPRA legislation contains loopholes and lacks enforcement mechanisms.

Existing Loopholes

NAGPRA falls flat when repatriating cultural heritage not culturally identifiable and not traceable to a contemporary and federally-recognized tribe. These limitations result in 73% of remains remaining in museum collections because they were deemed non-affiliable and not repatriable. “[T]he unaffiliated remains of more than 115,000 individuals and nearly one million associated funerary objects have sat on museum shelves in legal purgatory.” A March 2010 amendment, Disposition of Cultural Unidentifiable Human Remains, attempted to redress these limitations. Before the amendment’s enactment, a majority of ancestral remains were classified as non-affiliable and outside NAGPRA’s initial scope.

NAGPRA, in its current state, fails on multiple fronts. First, the amendment addresses unaffiliated ancestral remains, but does

(© President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, [24-15-10/94603 + 60740377])

Mimbres bowls, produced by people living in the Southwest from the late 10th to early 12th century A.D., are renowned for the unique imagery found on their interiors. The black-on-white ceramics were often decorated with geometric patterns.

not resolve the issue with funerary and sacred objects such as Mimbres bowls. Second, NAGPRA requires museums, federal agencies, and public institutions to consult with tribal governments in determining affiliation and recommendations of repatriation, yet this important step rarely occurs. Third, cultural affiliation rests upon the interpretation of a preponderance of evidence determined by the same collection of museums, federal agencies, and public institutions retaining the Indigenous American cultural heritage. Fourth, only federally-recognized tribes may bring repatriation claims, thus eliminating hundreds of tribes awaiting or denied federal recognition. Fifth, NAGPRA only applies to federally-funded institution and federal agency collections. Consequently, federally-funded institutions receiving promised gifts and loans from private collections circumvent NAGPRA responsibilities. Finally, NAGPRA established the Committee, made up of seven members, which reviews repatriation claims when requested by any of the involved parties. However, the Committee merely publishes non-binding advisory findings. Language not clearly explained by Congress can be reasonably interpreted by federal agencies provided they give adequate explanations, and thus provides major deference to agency decisions. Therefore, the current loopholes allow federal agencies and federally-funded institutions to act as the decision makers for repatriation claims, and leads to biased outcomes against the marginalized Indigenous American tribal communities.

Lacking Enforcement Mechanisms

Congress limited NAGPRA’s effectiveness by omitting dissuasive penalties for federal agencies and federally-funded institutions. In fact, the legislation is completely silent on penalties towards federal agencies. Subsequently, most federal agencies have not completed collection inventories, a process required to place tribes on notice of NAGPRA-protected cultural heritage and ancestral remains. NAGPRA required completed inventories no later than November 16, 1995, yet the Department of the Interior’s (“DOI”) agencies have failed at cataloging over 78 million cultural heritage objects and ancestral remains. Thus, tribal governments cannot place repatriation claims and have no course of action for dispute settlements.

The DOI’s Secretary assesses civil penalties to federally-funded institutions who fail to comply with NAGPRA. Nevertheless, federally-funded institutions frequently circumvent any penalties if they reasonably explain their decisions not to repatriate based on a preponderance of the evidence, regardless of the Committee’s recommendations. Legislation without adequate enforcement measures leaves agencies and institutions with too much power and tribal governments incapable of obtaining the just and fair outcomes sought.

For Indigenous Americans, NAGPRA continues to fail and fall flat on Congress’s goals thirty years later. Improper interpretation of NAGPRA and unfair results will continue without reconsidering the current legislation and elaborating upon the ambiguities. Next session, Congress should, at the very least, take action to close the NAGPRA's loopholes and add meaningful penalties. Even better, it should take this opportunity to completely rethink its approach to restoring and protecting the sacred objects of Indigenous Americans.

Tyler Heneghan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

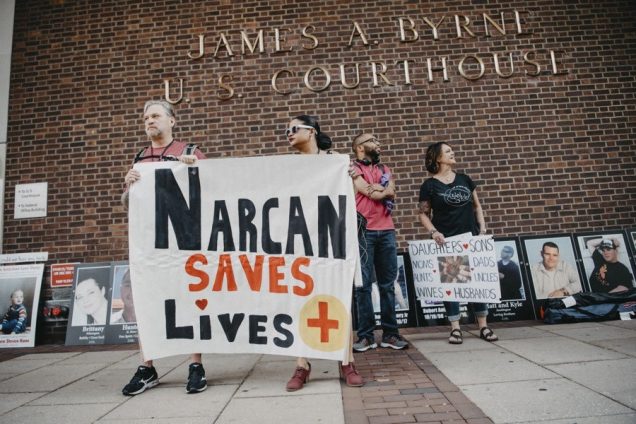

United States v. Safehouse: Could Philadelphia be the First State in the Nation to Implement a Supervised Drug Injection Site?

The opioid epidemic is one of the worst public health crises affecting the United States, and the rate of deaths resulting from opioid overdose has steadily increased. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a record high of more than 70,000 people died of a drug overdose in the United States in 2017, and over 47,000 of those deaths were from opioid overdoses. As lawmakers attempt to address this epidemic through public health initiatives , health advocates increasingly recommend using supervised injection sites to curb overdose deaths. Though legal barriers to this in the US exist, a recent District Court ruling in United States v. Safehouse may have paved the way for implementation of the first site of this kind in the US.

Injection sites provide a space where those using intravenous drugs can inject under the supervision of a medical professional ready to intervene in the event of an overdose, instead of unsupervised use where an overdose is more likely to be deadly. Supervised injection sites, also called safe injection facilities or safe consumption spaces, are a tertiary preventative public health measure aimed at combating overdose deaths and decreasing public use. In these spaces, injection drug users can self-administer drugs they bring to the facility in a controlled, sanitary environment under medical supervision. The medical personnel on staff at the sites do not directly handle the drugs and are there purely to administer Naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, in case of an overdose.

Despite the growing global presence in Europe, Australia, and Canada, scientific support for safe injection sites, and the interest of several cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Seattle, and San Francisco it is not entirely certain they can be operated in the United States. The Controlled Substances Act § 856, which regulates the production, possession, and distribution of controlled substances, makes it a criminal offense to maintain a drug-involved premises. Most academics agree that this “Crack House” Statute forbids safe injection sites and the courts can not definitively decide if safe injection site violate federal law until one is operational.

However, recently these assumptions have been called into question. Safe injection site proponents in many states have been appealing to legislatures and public health officials for funding. This effort has been largely unsuccessful due to political opposition and the looming threat of a federal lawsuit. In Philadelphia, which has the highest overdose rate of any major US city, a poll found roughly half of Philadelphians support a proposed safe injection site. Safehouse is a Philadelphia nonprofit that seeks to build the first safe injection site in the nation. In January 2018, Philadelphia health officials gave Safehouse permission to move forward with only private funds—preventing the need for legislative backing and appropriations.

In February 2019, federal prosecutors launched a civil lawsuit asking the U.S. District Court to rule on the legality of the Safehouse supervised consumption site plan, rather than waiting for the site to be built and then bringing federal criminal charges. U.S. Attorney William McSwain, working with Pennsylvania-based prosecutors, is seeking a declaratory judgment that medically supervised consumption sites per se violate 21 U.S.C § 856(a)(2)— the federal “Crack House” statute.

In February 2020, the court issued United States v. Safehouse, ruling that Safehouse’s plan to build a site where people could bring previously obtained drugs and use them under medical supervision for the purpose of combating fatal overdoses does not violate the Controlled Substances Act. Judge McHugh, looking at Congressional intent, ruled that §856 “does not prohibit Safehouse’s proposed medically supervised consumption rooms because Safehouse does not plan to operate them 'for the purpose of’ unlawful drug use within the meaning of the statute.” McHugh determines that at the time of enacting §856(a), Congress was focused on crack houses, not supervised drug injection sites. Even when amended in 2003, the focus was on “drug-fueled raves.” McHugh found that Congress neither expressly prohibited or authorized injection sites, so if §856(a) did not implicitly prohibit a consumption site, then implicit authorization naturally followed.

The question that the court addresses is whether the statute requires the defendant to know that third parties would enter their premises to consume illicit drugs, or rather that the defendant knowingly held their premises open for the purpose of facilitating illicit drug consumption. Judge McHugh concludes that the actor must “have acted for the proscribed purpose” to violate the statute. Therefore, the accused under a §856(a)(2) violation must have the purpose of facilitating illegal controlled substance use in the maintenance of a property.

Safehouse is planning “to make a place available for the purposes of reducing the harm of drug use, administering medical care, encouraging drug treatment, and connecting participants with social services.” The district court reasons that because of this, it could not conclude that Safehouse has, as a significant purpose, “the objective of facilitating drug use.”

In the wake of the ruling, U.S. Attorney McSwain announced that “this case is obviously far from over” and it is likely that the federal government will continue to litigate it. It is not unlikely that the Court that may hear this case on appeal disagrees with the District Court’s construction and strikes the legality of a supervised injection site based not on the intent of the person who controls the space, but the intent of the attendee of the site to use illicit drugs at that site, which has been the prevailing opinion up until the point of this ruling.

While the Safehouse case stands for an unexpected legal victory by way of the possibility of a supervised injection site to be opened in the United States, Philadelphia itself may not be the first state in the nation to implement one. The public sentiment in the wake of the decision was largely negative, with the local community being virulently opposed to the idea of a site being opened in the neighborhood from fear of what dangerous circumstances a site might attract. Plans to open the Safehouse site were put on indefinite hold. While proponents of Safehouse won the legal battle, winning over the community seems to be more of uphill battle than anticipated.

At this point in time, the legal position of supervised injection sites in the United States is tentatively positive. States who are looking to introduce this harm reduction initiative, and to be the first in the nation to do so, should take the opportunity to garner support from legislatures and local health care communities. While Philadelphia’s progression seems to be stymied, the District Court’s ruling provides significant legal precedent to ground encouragement for sites to be lobbied for in other states or cities that might not face the same type of community rejection that has prevented the opening of Safehouse.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Zahraa Badat anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Waiting Game: Supreme Court’s Decision on the Lawfulness of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program

As May 2020 comes to an end, many eagerly await a Supreme Court decision that could affect the futures of thousands of DACA recipients and shape immigration policy as we know it. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is the program that is currently under scrutiny; in particular the Supreme Court will be deciding on the following two issues: (1) “Whether or not the Trump administration’s decision to end DACA can be reviewed by the courts at all?” and (2) “Whether or not the Trump administration’s termination of DACA was lawful?” This program was first instituted under the Obama Administration as an executive action to do the following for qualified Dreamers who completed the process of a first-time or renewal application: (1) protection from deportation for a time period, and (2) work authorization for a set period of time.

During the Obama Administration, the DREAM Act of 2010 (H.R. 6497) was proposed and passed in the House but did not pass the Senate. The purpose, like its other variations, was intended to aid undocumented individuals by providing them a way to eventually reach legal status, because they were brought to the United States when they were children and have to live with a continued sense of uncertainty that attaches to being undocumented. In its stead, the Obama Administration designed a temporary solution, which came to be known as DACA, in which an individual could qualify by meeting a series of requirements (i.e. arriving in the United States before they turned sixteen years old).

This policy gave a lot of individuals hope, but everything changed with the arrival of the Trump Administration. The Trump Administration’s policies quickly took on an anti-immigration rhetoric, and his Administration rescinded the policy on the basis that it was illegal. Thereafter, lawsuits followed with Department of Homeland Security, et al., v. Regents of the University of California, et al. reaching the Supreme Court level.

Regarding the two issues laid out above, there are many ways the decision could go, but the one that would have the worst effect on DACA recipients would be the court siding on the Trump Administration’s side in saying that “DACA was an unconstitutional use of presidential power to begin with.” This could have a devastating impact on DACA recipients especially at a time when they find themselves in the midst of the COVID-19 global pandemic alongside the rest of the world.

For example, ABC News quotes a college student saying “As a DACA recipient, and everything going on with COVID-19 and as well with the Supreme Court ruling coming at any time -- It's been very stressful.” On top of college, she works with authorization under DACA, but COVID-19 has added other stressors as she finds herself as the only provider at home. Ending DACA at a time like this would end up being very challenging and harmful for individuals like these who are trying to stay afloat during this pandemic.

Nevertheless, as this country struggles to recover from this pandemic, the most interesting development has happened to this Supreme Court case showing how vital Dreamers and immigrants have been to making this country function smoothly despite the havoc wreaked by the virus. A CNN report discusses how: “A letter sent to the Supreme Court states approximately 27,000 Dreamers are health care workers -- including 200 medical students, physician assistants, and doctors -- some of whom are now on the front lines in hospitals across the country.” The Supreme Court agreed to take this brief into consideration, and it makes one wonder whether the timing of the decision during a pandemic and the supplemental brief will have any impact at all?

Nevertheless, as this country struggles to recover from this pandemic, the most interesting development has happened to this Supreme Court case showing how vital Dreamers and immigrants have been to making this country function smoothly despite the havoc wreaked by the virus. A CNN report discusses how: “A letter sent to the Supreme Court states approximately 27,000 Dreamers are health care workers -- including 200 medical students, physician assistants, and doctors -- some of whom are now on the front lines in hospitals across the country.” The Supreme Court agreed to take this brief into consideration, and it makes one wonder whether the timing of the decision during a pandemic and the supplemental brief will have any impact at all?

Despite the positive contributions of these and other essential individuals, there have been a lot of issues that have also surfaced reflecting further difficulties that Dreamers are enduring. An example of this is federal funding under CARES Act. The pandemic has had even more disastrous effects on particular communities, and though the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 was passed with a part of it designed to provide aid and federal dollars to help students, and yet the benefits are not available to everyone. DACA students could not qualify to receive money under this Act, and it was one of the reasons the Democrats reached out to Secretary DeVos to change the language but to no avail. The House has brought another bill to the forefront, the Heroes Act, which proposes many changes; one aspect of which directly seeks to overturn “Secretary DeVos’s decision to exclude DACA students from the emergency aid.”

This is a hopeful change, but the culmination of issues including the Supreme Court decision yet to be released, the uncertainty of COVID-19 on employment, health, and education, and a delay in passing the House bill paints a bleak picture.

Yet, at the end of the day, it is as Antonio Alarcon described it on CNN: “We’re hopeful that the Supreme Court will see the humanity of our stories and see the humanity of our families, because at the end of the day, this is a nation of immigrants.”

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

The Fear of Forcible Eviction: Deficiencies in India’s Forest Rights Act’s Recognition of Indigenous Land Rights

Land rights has been an ongoing issue in India for many years now, but there are some communities that end up being more vulnerable than others. This was made clear on February 13th, 2019, when the Supreme Court of India released an order for mass evictions of indigenous forest dwellers from forest areas for the goal of conserving these lands. Here, the conflict itself is not surprising because evictions has been a persistent issue throughout Indian history, but it is the degree of how many individuals would be impacted that made this news so surprising.

This order was later stayed for the purpose of asking states to provide more details on the steps of eviction due to the nearly one  to two million indigenous people who would be affected by the declaration. This order is significant for illustrating the deficiency in current legislation and also for shedding light on the consequences faced by vulnerable communities who live in fear of being forcibly evicted from lands that they live on, depend on, and survive on. This article will lay out the process and current critiques of the FRA, and further discuss the ongoing arguments for and against the mass eviction ordered in the February 13th decision.

to two million indigenous people who would be affected by the declaration. This order is significant for illustrating the deficiency in current legislation and also for shedding light on the consequences faced by vulnerable communities who live in fear of being forcibly evicted from lands that they live on, depend on, and survive on. This article will lay out the process and current critiques of the FRA, and further discuss the ongoing arguments for and against the mass eviction ordered in the February 13th decision.

Forest Rights Act of 2006

Enacted in 2006, the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act (commonly referred to as the Forest Rights Act (FRA)) was intended to protect indigenous populations. The FRA sought to substantiate and recognize land claims of forest dwellers. The FRA brings two groupings of individuals within its purview:

- Forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes, which includes members of Scheduled Tribes who primarily reside and live off the land, and

- Other traditional forest dwellers, which includes anyone who can prove that they have resided on and lived off the land for “at least three generations.”

To obtain legal recognition of their land rights individuals must file a three stage claim.

- Stage 1: The first stage begins at the level of the Gram Sabha, which is generally a village assembly at which a person presents their claim to the land. At this assembly people are elected to the Forest Rights Committee, which investigates the claim and presents its findings to the village assembly. Acceptable forms of proof to support a land claim are governed by Rule 13 of the Comprehensive Tribal Rules.

- Stage 2: After the Forest Rights Committee presents findings to the village assembly, the second stage begins with the review of the claim by the Sub-Divisional Level Committee.

- Stage 3: Thereafter, the third stage is set at the District-Level Committee which determines the fate of the claim; either a claim will be accepted or rejected. If rejected, an appeals process is available to the claimant, but it is uncommon.

Despite being considered a step forward, the FRA’s deficiencies serve to negatively impact indigenous forest dwellers.

- Inexperience: First, there is the issue of inexperience with the legal system as this Act imposes a legal process that these groups may be unfamiliar with and therefore will find it more difficult to complete fully and accurately.

- Inaccessibility: Second, there is the issue of inaccessibility, because the Act imposes a standard form, but does not consider diversity (i.e. approximately 705 diverse ethnic groups that are legally recognized) and how such a form could be inaccessible to individuals not speaking the same language or who have different customs on resolving disputes.

- Impractical: Third, there is the issue of impractical standards. As the definition of the other traditional forest dwellers mentioned above indicates, part of the process of getting the land right recognition requires a claimant to present proof of residence in the forest area for at least three generations. The following two factors show how this is not a practical standard:

- First, having difficulty preserving documentation that dates so far back when living a nomadic way of life,

- Second, it be unlikely to have had an opportunity or need to compile such documentation beforehand.

- Inadequacy: Lastly, there is the issue of inadequacy, as this procedure is set up in a way that can be influenced by adverse interest groups who may have alternate plans for the forest areas that indigenous groups call home.

These deficiencies illustrate how complex the issue is, and how there are a number of structural issues that need to be resolved in order to provide the protection that these groups need.

Arguments For And Against Forced Evictions

The February 13th order is unclear on the forced eviction of indigenous groups. Those opposed to indigenous groups residing in forest lands claim that the current destruction of forest areas is attributable to indigenous dwellers whose practices and way of life prove to be harmful to these areas. Furthermore, opponents such as the conservationists are not entirely sold on the purpose the FRA serves in recognition of land rights.

Supporters of indigenous forest dwellers, however, characterize these dwellers as the forest’s guardians because their practices prove to be less harmful to the land. Having resided on the land for many generations, their history, culture, and practices are tied with the land in an inexplicable way, and so evictions can prove to be disastrous to these communities especially when they are executed through force.

There have been many incidents when forced evictions have been executed through use of force (i.e. threatening behavior, destruction of home, etc.). Such evictions are expected to have dire consequences for evicted individuals, but with communities as cohesive as indigenous groups the consequences are even more far reaching. Not only are they at risk of induced poverty and danger, but community and social life are broken down forever.

These consequences indicate a systemic and pervasive issue that requires resolution. The starting point for this is amending the FRA by making it simpler and stronger by addressing the deficiencies listed above. Only through amending this Act can real change begin to happen.

Note: This article is based on a paper originally submitted in the Environmental Justice class at BU Law.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Nabaa Khan anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2021.

Is the Johnson Amendment Constitutional?

My previous Dome blog entry discussed the Johnson Amendment and the fight that has surrounded the amendment since its creation in the 1950s. The Johnson Amendment was added to Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. tax code by then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson to limit the political activity of 501(c)(3) organizations. The Amendment prohibits 501(c)(3) organizations from endorsing or opposing political candidates. Many organizations have been trying to repeal the Johnson Amendment for years, and many argue (including members of Congress) that it violates the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Two vocal opponents of the Johnson Amendment (and the sponsors of the Free Speech Fairness Act in both houses of Congress) Senator James Lankford and Congressman Steve Scalise argue that the Amendment must be repealed to protect the First Amendment rights of 501(c)(3) non-profit employees. They argue the Bill of Rights protects the right of all Americans to freely express their ideas and opinions without persecution from the government, and the Johnson Amendment violates this right by stripping 501(c)(3) employees from being able to speak their minds about political issues. As discussed in my previous post, the Johnson Amendment prohibits 501(c)(3) employees from endorsing or opposing candidates, and violations of the Amendment risks punishment by the IRS either by fine, revocation of the organization’s tax-exempt status, or both. This, therefore, begs the question of whether the Johnson Amendment does in fact violate the First Amendment. This Dome blog post will look at legal precedent to see if the Amendment has been challenged for its constitutionality in the past, and if so, the arguments the court made in their decision.

Before going into court cases about whether or not the Johnson Amendment actually violates the First Amendment, it is important to look at the text itself. The text of the First Amendment reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Members of Congress and other organizations who oppose the Johnson Amendment mainly argue that it violates the freedom of speech, which is in fact why the current bill before Congress attempting to repeal the Amendment is titled the “Free Speech Fairness Act.” Within the text of the First Amendment, they argue that the Johnson Amendment is “abridging the freedom of speech” of 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit employees, but in particular religious ones, such as pastors, priests, and rabbis.

But has the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment actually been determined by the Supreme Court as it applies to religious organizations? The answer, unfortunately, is no. However, two U.S. Court of Appeals circuits have upheld the Amendment as constitutional in the past when applied to religious organizations. The first case, Christian Echoes Nat'l Ministry v. United States (1972), involved a nonprofit religious corporation contesting the revocation of its 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status by the IRS as punishment for violating the Johnson Amendment. Through various appeals and remands, the ultimate holding by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals was that the organization no longer qualified as a tax exempt organization under section 501(c)(3) of the tax code. As one argument against the revocation of their status, Christian Echoes argued the Johnson Amendment was unconstitutional and violated their right to free speech. However, the court held that “in light of the fact that tax exemption is a privilege, a matter of grace rather than right... the limitations contained in Section 501(c) (3) withholding exemption from nonprofit corporations do not deprive Christian Echoes of its constitutionally guaranteed right of free speech.” Christian Echoes Nat'l Ministry v. United States, 470 F.2d 849, 857 (10th Cir. 1972). The court therefore determined the taxpayer must refrain from these political activities to obtain “the privilege of exemption,” which Christian Echoes benefited from until their status was revoked.

The argument made by the court in Christian Echoes is very similar to the argument made by proponents of the Johnson Amendment, such as the Freedom From Religion Foundation, who argue because religious organizations benefit essentially from a government subsidy, in exchange for that subsidy they relinquish some of their rights. These rights can at any time be reclaimed, but at the cost of losing the subsidy, ultimately leaving the choice between the two up to individual organizations.

The District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals has also taken up this issue more recently in Branch Ministries v. Rossotti (2000), regarding the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment, but for violation of a different part of the First Amendment. In this case, a church had its tax-exempt status revoked for intervening in political campaigns, violating the Johnson Amendment. The church argued that revoking their tax-exempt status was a violation of the Free Exercise clause of the First Amendment, as in violating their right to freely exercise religion. To show the Free Exercise clause had been violated, the church had to establish their “free exercise right has been substantially burdened.” Branch Ministries v. Rossotti, 211 F.3d 137, 142 (2000). The court, however, held the Johnson Amendment did not violate the First Amendment because the church failed to establish that their free exercise right had been substantially burdened. Despite the claim by the church that by revoking their tax exempt status would threaten its very existence, the court determined this was overstated because the impact of revocation “is likely to be more symbolic than substantial,” because if they stop intervening in political campaigns they can regain their tax-exempt status, and even if they do not, “the revocation of the exemption does not convert bona fide donations into income taxable to the Church.” Therefore, the burden is not substantial enough to be considered a violation of the First Amendment. See, Branch Ministries, 211 F.3d at 142-143.

It seems currently that courts are finding the Johnson Amendment does not, in fact, violate the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has said in the past they believe tax benefits nonprofits are given are “a form of subsidy that is administered through the tax system,” which seems in line with the view of supporters of the Johnson Amendment and these two Court of Appeals cases. See, Regan v. Taxation with Representation, 461 U.S. 540, 544 (1983). They have not, however, delivered a decision on the constitutionality of the Johnson Amendment as it applies to religious organizations. Therefore, despite the Court of Appeals cases, the fight over this issue is unlikely to end until the Supreme Court formally rules on the Johnson Amendment as it applies to religious organizations once and for all.