Category: Analysis

WHO LET THE DOGS OUT? CALIFORNIA BANS USE OF PUPPY MILL

In October 2017, California became the first state to pass a law to deter the use of puppy mills by potential puppy buyers. Under the new law, pet stores must work with animal shelters and other rescue operations to obtain dogs, cats and rabbits, and are prohibited from using breeders. However, private and individual customers can still use puppy mills, and nothing in the act adds direct regulations on domestic animal breeders in the state.

Over the past several years, there has been a nationwide conversation among pet lovers about the ethics of puppy mills. At the center of the debate is the competition for owners between adoption/rescue groups, and breeders. According to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), 34% of currently owned dogs were raised by a breeder, as opposed to 23% coming from an animal shelter or other humane rescue group. Origination data is not entirely clear however, as the American Humane Association (AHA) and the American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA) put breeder-acquired ownership figures at less than 20%. Shelter-based ownership figures vary even more, with the AVMA putting the adoption population at 84.7% and the AHA estimating a 22% adoption population. Available figures for breeder-acquired cats are below 5%. While it is difficult to claim that adoption and rescue agencies are at a disadvantage for owners strictly because of breeder competition, the sheer number of pets in shelters (5-8 million dogs and cats) and getting euthanized every year (3-4 million dogs and cats), makes many wonder why people use breeders at all. Proponents of laws like California’s believe that people who buy breeder-bred animals could have instead adopted an animal from a shelter.

Over the past several years, there has been a nationwide conversation among pet lovers about the ethics of puppy mills. At the center of the debate is the competition for owners between adoption/rescue groups, and breeders. According to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), 34% of currently owned dogs were raised by a breeder, as opposed to 23% coming from an animal shelter or other humane rescue group. Origination data is not entirely clear however, as the American Humane Association (AHA) and the American Veterinarian Medical Association (AVMA) put breeder-acquired ownership figures at less than 20%. Shelter-based ownership figures vary even more, with the AVMA putting the adoption population at 84.7% and the AHA estimating a 22% adoption population. Available figures for breeder-acquired cats are below 5%. While it is difficult to claim that adoption and rescue agencies are at a disadvantage for owners strictly because of breeder competition, the sheer number of pets in shelters (5-8 million dogs and cats) and getting euthanized every year (3-4 million dogs and cats), makes many wonder why people use breeders at all. Proponents of laws like California’s believe that people who buy breeder-bred animals could have instead adopted an animal from a shelter.

Another facet of the “puppy mill” debate is the living conditions in breeder facilites. Claims of animal cruelty plague the reputation of breeder businesses. Though breeder operations are governed by Federal USDA regulations and inspections, irresponsible breeders can evade these oversights and sell animals that have been bred improperly, leading to pets with physical and psychological ailments. Many times, these irresponsible breeders will focus on quantity, instead of quality of the animals (hence the term “mills”) possibly leading to poor health, abandonment, or even death of the animals. Since these disreputable breeders often sell to pet stores, instead of directly to screened buyers, laws like the one California just passed will likely serve as a significant deterrent for negligent breeders. However, some detractors of the bill say many cities statewide (including LA, San Diego, and San Francisco) already ban “mass breeding” and other unhealthy practices, so this new law is more likely to constrain the breeders who do not engage in these poor practices, yet sell to pet stores, than the irresponsible breeders.

Aside from animal welfare, steering potential pet owners and pet shops to animal shelters should benefit the state’s taxpayers. Publically run animal shelters cost the state approximately $300 million a year. If this law has its intended effects and decreases overcrowding in animal shelters, the state can accordingly decrease spending on housing, feeding, and servicing shelter animals. While California may pinch some pennies with decreased animal shelter populations, the breeding community may suffer economically under this bill. California has roughly 800 active breeders selling animals in the state. Even if only a small percentage are fully reliant on pet stores for income, that is still dozens of California’s workers being effectively forced out of a job under this law. However, some of this job loss may be offset by impacted breeders selling to out-of-state pet stores who do not have similar laws.

Though California’s new law was a key win for anti-puppy mill and animal welfare advocates, there are still some detractors. For example, this law may present challenges to those seeking specific breeds for their pet. Consumers may no longer easily get breed specific animals in pet stores, and specific breeds may become more costly. This might be particularly cumbersome for someone looking for a service animal of a particular breed best suited to help manage a condition. The American Kennel Club released a statement saying the law “not only interferes with individual freedoms, it also increases the likelihood that a person will obtain a pet that is not a good match for their lifestyle and the likelihood that that animal will end up in a shelter.” Further, this legislation may have the unintended consequence of increasing animal deaths and abandonment at puppy mills, because the mills no longer have access to their main customers. If the mills have not sold off all their animals by the 2019 effective date of this law, the animals may have nowhere to go. Breeders whose business is hurt as a consequence of this law may spend even less money on the care of the animals, or be forced to surrender the animals to a shelter. But given the delayed effective date of the law and the continued legality of breeder use by individual parties, the foreseeable issues will likely be negligible in light of the positive changes.

Since California passed this law, a Massachusetts lawmaker has also proposed a similar bill that would deter the practice of commercial breeding. Though California is the first state to pass this kind of prohibition, cities all over the country have been passing similar ordinances, so it is likely that states will follow suit if California’s law works as intended.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Inter Partes Review: non-Article III Adjudication of Private Property Rights

In November 2017, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group. Oil States poses a question that forces the Supreme Court to consider whether it will turn patent strategy on its head: whether inter partes reviews (IPRs) violate the Constitution by extinguishing private property rights through a non-Article III forum without a jury. The Federal Circuit is notoriously the appellate circuit most reversed by the Supreme Court – by May 2017, the Court had reversed 25 of the 30 cases it accepted from the Federal Circuit. Will Oil States suffer the same fate?

An IPR, established as one of the cornerstones of the American Invents Acts (AIA) in 2011 and initiated in 2012, is a proceeding instituted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), upon petition by an outside party, allowing parties to challenge the validity of an issued patent before the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB), a non-Article III tribunal. Congress created IPRs primarily to increase the efficiency of an otherwise expensive and time consuming traditional patent validity challenge in court. While traditional patent litigation may consume millions of dollars and years of the parties’ time – a waste of financial and judicial resources and creating uncertainty within the field of technology encompassed by the patent – an IPR typically costs the parties a comparatively small six figure sum and the AIA requires the PTAB to issue a final written decision within one year of IPR institution.

Since 2012, IPRs have become a popular mechanism for parties to challenge the validity of patents – in part due to their efficiency and in part because the PTAB does not begin with a presumption of validity, whereas courts do. In effect, the PTAB has invalidated all claims of the challenged patent in over 1,200 proceedings, roughly 74% of all IPRs. Only 13% of IPRs result in no claims of a patent being invalidated.

The courts have already disposed of numerous challenges to the constitutionality of patent validity review procedures conducted before the USPTO. Before the AIA introduced IPRs, the USPTO had already been invalidating patents since 1981 via ex-parte reexamination. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly affirmed the constitutionality of the USPTO’s authority in such proceedings, stating that “[a] defectively examined and therefore erroneously granted patent must yield to the reasonable Congressional purpose of facilitating the correction of governmental mistakes.” Patlex Corp. v. Mossinghoff, 758 F.2d 594, 604 (Fed. Cir. 1985). The Federal Circuit has more recently denied a similar constitutional challenge to IPRs, stating that patent rights are public rights, reviewable by an administrative agency, and therefore assigning review of patent validity to the USPTO is consistent with Article III. MCM Portfolio LLC v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 812 F.3d 1284, 1291 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

Oil States challenged IPRs alleging a violation of both Article III and the Seventh Amendment. Concerning Article III, Oil States argued that it is unconstitutional for a non-Article III court / Article I tribunal to adjudicate private property. Oil States argued that the Seventh Amendment guarantees patent owners the right to a jury trial because historically, patent infringement cases have been heard in courts of law in England before juries.

Oil States argued that the Supreme Court has once before reviewed and disavowed USPTO patent validity review procedures (otherwise, the Court has only denied certiorari in the past to review Federal Circuit decisions treating the question, including the two above decisions) and the differences in the statutorily created IPR and ex parte reexamination.

In 1898, the Supreme Court held that “the Patent Office has no power to revoke, cancel, or annul” an issued patent. McCormick Harvesting Mach. Co. v. Aultman & Co., 169 U.S. 606 (1898). However, this case did not concern the constitutionality of such proceedings, and it is likely that the Court will limit McCormick to the narrow position that the USPTO does not exercise jurisdiction over an issued patent in the absence of authorization from Congress, as was lacking in 1898. Now that Congress has expressly authorized such review via the AIA, the Court will likely find such review constitutional.

Oil States highlights the differences between AIA-created IPRs and ex parte reexaminations; IPRs are adversarial proceedings including discovery, briefings, hearings, and a final judgment, whereas ex parte reexaminations are more akin to interactive proceedings between the agency and patent owner.

To resolve this case, the Court will likely stay away from disclaiming the statutory distinctions establishing IPRs as trial-like proceedings, because these hold some legitimacy, and focus on whether a patent is a public or private right. If a patent is a public right, then there is no issue with IPRs being trial-like proceedings conducted before non-Article III adjudicators because it is proper for an agency to adjudicate a public regulatory scheme. If, on the other hand, patents are private rights, as Oil States contends, then the Court would be forced to either disavow IPRs or distinguish their characteristics from a trial. The Federal Circuit provided the Court with a mirror distinguishing IPRs from traditional trials, but this distinction is fragile at best. Ultratec, Inc. v. Captioncall, LLC, 2017 WL 3687453, *1 n.2 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2017). The Court would find more stable grounding classifying patents as quintessential public rights, conferred only by virtue of a statute.

The most curious note regarding the Supreme Court’s decision to hear Oil States is that it concurrently agreed to hear SAS Institute v. Lee, which asks the Court to consider whether the AIA permits the USPTO to select claims from a petition and partially institute an IPR or whether the USPTO must wholly grant or deny a petition, either blessing or damning all claims. If the Court intends to destabilize the AIA and declare IPRs unconstitutional, why consider the USPTO’s duty to the petitioner for an IPR in the same term? It is likely that the Supreme Court will uphold the constitutionality of the AIA’s grant of authority to the USPTO and permit IPRs to continue, but will use these two cases as an opportunity to either limit the scope and effect of IPRs or force clarity regarding the deficiencies of IPRs – such as lacking judicial rules of ethical conduct, improper handling of evidence, improper handling of amendments, or simply disregarding established standards in favor of PTAB-created standards.

Eric Dunbar anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Personalized Handgun Law Backfires, by Merissa Pico

Like a gun might, this New Jersey legislature’s bill backfired. In 2002, New Jersey’s democratically controlled legislature passed the Childproof Handgun Law, which aimed to promote the use of personalized handguns.

Personalized guns, or “smart guns,” as they are also known, use technology so the guns can only be used by an authorized or recognized user.

The 2002 law, which was signed into law by then Governor James McGreevey, requires all handguns sold in New Jersey to be smart guns within 30 months of personalized handguns becoming available anywhere in the country. The statute tasks the New Jersey Attorney General with determining which handguns qualify as smart guns and when smart guns have become available as set forth under the law. In other words, it would not matter if a smart handgun was actually sold or not; as long as a smart handgun was available for sale anywhere in the nation, the clock would start and within 30 months, all handguns sold in New Jersey would have to be smart guns.

According to the 2002 law’s sponsor, New Jersey State Senate Majority Leader Loretta Weinberg (D-Bergen), the 2002 law’s objective was to stimulate the “research, development and manufacture” of smart guns.

Ironically, but perhaps not surprisingly, the law has had the opposite effect: it inadvertently stunted the availability of personalized handguns nationwide. Fifteen years since its enactment, smart handguns are still not available for purchase in the United States. This is despite the fact that the technology exists; smart guns are available for sale in Europe and Asia.

Viewing the New Jersey law as an attack on the second amendment, the pro-gun sector has stifled any movement in making smart guns available. In addition to one gun store in California, in 2014, one Maryland gun storeowner, Andy Raymond, set out to sell the first smart gun in the nation. However, like the California store, Raymond decided not to go through with making smart guns available for sale, after both received hundreds of protests on his store’s Facebook page as well as death threats. If Raymond or the California store had successfully done so, the thirty-month clock in New Jersey’s 2002 law would have started, an effect that the pro-gun sector was well aware.

While it is clear that the 2002 law effectively entrenched the standstill on smart gun development, it should be noted that the pro-gun lobby has not necessarily embraced the smart gun initiative with open arms over the years.

Opponents of the 2002 law have objected to the state-mandated market for smart guns, believing that a market for smart guns, if there should be one, should emerge without any government intervention. Further, many gun owners have concerns about the reliability of the smart gun technology, fearing that the technology will falter when and if they need it to protect their lives.

An attempt to fix this legislative conundrum that New Jersey's legislature created for themselves and the rest of the country, the legislature in 2016 introduced a new bill, S816, to amend the 2002 law. Also sponsored by Senator Weinberg, S816 would repeal the portions of the 2002 law that would have made it illegal to sell traditional handguns once personalized hand guns become available, thereby effectively eliminating the technology freeze. Additionally, S816 mandates that firearms merchants and dealers maintain an inventory of at least one model of smart gun to sell. Under the bill, the Attorney General would determine on which smart guns would be acceptable.

The democratically controlled New Jersey senate approved the bill in February of 2016 by a vote of 21-13. New Jersey governor and former 2016 U.S. Presidential candidate, Chris Christie, pocket vetoed the bill in September of 2016. A pocket veto means that the governor does not return the bill to the New Jersey legislature; therefore, the veto cannot be overridden. In his strongly worded conditional veto message, Governor Christie said the new bill was the latest in the “relentless campaign by the Democratic legislature to make New Jersey as inhospitable as possible to lawful gun ownership and sales.” Believing that the new bill’s mandate is a constraint on business and “likely is unconstitutional under the Commerce Clause,” Governor Christie went on advocate for a full repeal of the 2002 law with no additional mandate.

With the bill having been pocket vetoed and sent back to the statehouse, the New Jersey legislature can either amend the bill to Governor Christie’s liking or it will die in the state senate. If the bill dies, the 2002 law will remain in place in its entirety without any amendment. Therefore, until it is amended or repealed, the law could continue to have the same stifling effect on nation-wide smart gun availability into the unforeseen future.

Senator Weinberg has publically offered to repeal the 2002 law in its entirety if the National Rifle Association (NRA), promised to not impede or block the “research, development, manufacture or distribution of this technology.” However, to date, there has not been any movement on this offer.

It is frequently said that the law lags behind technology. More often than not, this is true (see 1986 Electronic Communication Privacy Act). Yet, this time, the law and legislative process is not lagging behind technology, but rather, with full recognition and understanding, is choosing to stifle technology. Who knew that a little New Jersey law would have such an unintended consequence? For fifteen-years and counting, partisan division and policy differences have kept available technology out of reach from American citizens. Perhaps soon, the technology will become available under conditions favorable to all Americans, politicians and private citizens alike.

Merissa Pico is from Fort Lee, New Jersey and graduated summa cum laude from Boston University’s College of Communication in 2015 with a B.S. in Mass Communication Studies. She is expected to earn her J.D. from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Merissa will be working at Ropes & Gray in New York City in the summer of 2017 and is looking forward to continuing to explore her interests in entertainment and communications law.

Merissa Pico is from Fort Lee, New Jersey and graduated summa cum laude from Boston University’s College of Communication in 2015 with a B.S. in Mass Communication Studies. She is expected to earn her J.D. from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Merissa will be working at Ropes & Gray in New York City in the summer of 2017 and is looking forward to continuing to explore her interests in entertainment and communications law.

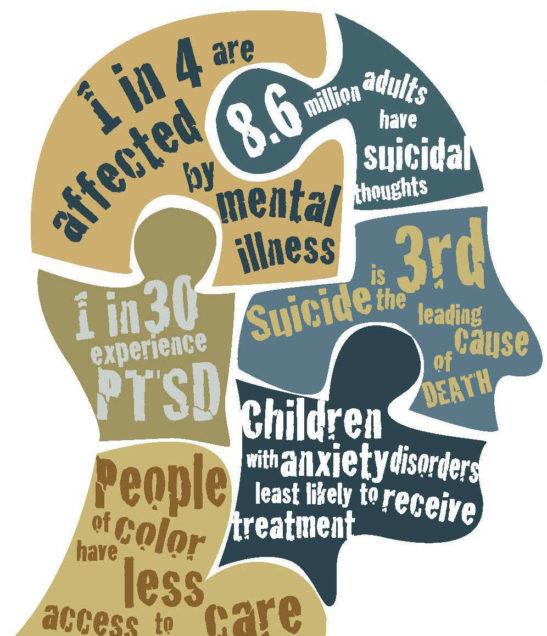

Finding Equity in Mental Health Reform

Mental health has been a very serious topic in recent years, and one of growing concern in American society. Mental illness among teenagers continues to rise, and so do the costs of mental health treatment. Health care in general is a major and complicated issue in the United States, as Republicans in Congress found in their attempts to repeal and replace the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”). In recent decades federal and state legislation have greatly improved access and provided needed consumer protections, but many of the most important protections are in jeopardy. If current Congressional action is any indication, mental health reform may take several steps backward under the new administration.

Mental health reform became a federal issue in 1996 when Congress passed the Mental Health Party Act (“MHP”). It was a weak first attempt at fixing persistent problems in the American health insurance market. Up until the passage of the MHP, insurance providers openly discriminated against mental health claims and treatment. The MHP was the federal government’s attempt to address the disparity between mental health coverage and traditional medical/physical health coverage. However, the original MPH was gutted in Congress before passage, leaving behind a weak law that barely fixed disparities and discrimination in mental health coverage.

During the congressional debates to get the MHP passed, many were concerned about the economic and practical costs of the initiatives to provide equal protections for mental health and medical care. However, the major success of the MHP was that it demonstrated to lawmakers that providing coverage for mental health treatments was not only beneficial, but that it could be done in a cost effective manner.

After the passage of the 1996 Act, the states responded and attempted to bridge some of the gaping holes left by the MHP. In many cases, states created stricter mental health parity laws than the federal government. This sparked a general acceptance and trend toward improving mental health parity. As opposition to mental health parity was drowned out by support for increased regulation and consumer protections, Congress felt encouraged to try their hand again at providing equal treatment for mental and medical health coverage. The 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (“MHPAEA”) was the result of Congress’s second try. The MHPAEA greatly expanded protections for mental health patients and treatment coverage. But alas, there were still major areas in need of reform.

Of particular importance to the current and future state of mental health reform though, came two short years after the passage of the MHPAEA - the ACA. Passed in 2010, the ACA combined with the MHPAEA brought sweeping reform for mental health coverage. Mental health coverage falls under the Essential Health Benefits mandate requiring every insurance provider to provide consumers with mental health coverage. Coupled with the MHPAEA, which requires any insurance provider to treat mental and medical claims equally, mental health coverage is now equal in the eyes of the law to medical coverage.

Since the passage of the ACA though, the practical impact of the reforms have resulted in more covert discrimination of mental health claims that are chipping away at important health care resources that are increasingly vital in American society. Despite laws requiring equal treatment, insurance providers decline mental health claims at higher rates than medical claims. Additionally, insurance providers also make it hard for mental health treatment providers to get paid thereby limiting the physical amount of help available.

The ACA made significant gains in mental health reform, however the lack of practical results has preserved mental health reform as a serious issue of concern. Recently, Congress enacted the 21st Century Cures Act (“Cures Act”), which addresses many pressing concerns that were not covered under the ACA. Most notably, the new act uses modern ideas to address mental illness concerns and substance abuse issues. However, a major concern with the Cures Act is that despite its passage, the House must choose to fund it. Otherwise, all the legislative action prescribed by the new federal law is moot.

Unfortunately, many are speculating that Congress and the Administration will be at odds over the budget putting federal funds for mental health in jeopardy. This is especially so given the fight over funds for various Republican and Presidential pet projects. For example, the President is strongly urging the Republican controlled Congress to allocate funding for his pet project, the border wall between the United States and Mexico. However, House Speaker Paul Ryan and many Republican representatives are more interested in changing funding allocations for health care in an attempt to bounce back after the humiliation of their previous attempt at altering the ACA.

If the recent efforts to "repeal and replace" the ACA was any indication of what the future holds for mental health reform, then America will take a step backward leaving millions without coverage thereby exacerbating an already growing problem. The House passed AHCA attempted to gut the ACA, and would have remove the individual mandate and significantly altered the Essential Health Benefits requirement. Under the AHCA, Ryan tried to remove the requirement that Medicaid and Medicare must follow the Essential Health Benefit mandate, which would effectively prevent millions of the most vulnerable in society from accessing affordable mental health resources.

The fate of mental health coverage and treatment access in many ways is tied to the continued success and longevity of the ACA and funding options for current mental health legislation. To remove the current federal mental health protections, as was proposed in the AHCA, would set progress back and make it nearly impossible for millions to have access to affordable mental health treatments. As the need for mental health treatments and resources grows, we as a nation should not be removing protections and federal funding for progressive initiatives. We should continue to follow the path of the Cures Act and further pursue these initiatives. In order for mental health treatment to be improved subsidies need to be provided for mental health treatment providers (such as psychologists) to incentivize them to open practices and facilities in critical shortage areas. Additionally, federal and state regulations need to address the manner in which insurance providers treat mental health providers.

The current legal framework as a whole is very fair, but needs stricter enforcement on the ground. What use are laws and protections if no one is incentivized to follow them? Of the greatest important, however, is that future laws and regulations intending to improve the state of mental health coverage need to stop attempting to create equality between mental health and medical treatment. Medical and surgical procedures are inherently different than mental health procedures and thus legal equity is needed in order to improve access and provide needed consumer protections.

Is There Such a Thing as Free College?

New York became the first state to make tuition free for two- and four-year colleges for certain students. Governor Andrew Cuomo first introduced his Excelsior Scholarship plan in January 2017, and signed it into law in April 2017. New York State’s Excelsior Scholarship will provide free tuition to students whose families earn less than $125,000 for all public two- and four-year colleges in New York, covering State University of New York (SUNY) colleges as well as City University of New York (CUNY) colleges. The estimated cost if this Excelsior Scholarship is $163 million, amounting to only 0.1% of New York State’s budget. Governor Cuomo, in announcing his plan, said “In this economy, you need a college education if you’re going to compete.” He explained, “It’s incredibly hard and getting harder to get a college education today. It’s incredibly expensive and debt is so high it’s like starting a race with an anchor tied to your leg.” Based on projections, around 940,000 New York households have college-aged children who would qualify for the program.

“[T]he cost of attending college has risen at a much faster rate than the median income, putting even middle-class families in a tough spot when trying to figure out how to finance their children’s college education.” According to the Institute for College Access and Success, about 59% of students graduate from New York’s four-year colleges with debt, on average about amounting to $29,320 of debt. The program will work by giving a scholarship to students whose existing federal and state need-based loans do not fully cover the $6,470 list price tuition at public institutions. Students who currently pay no tuition out of pocket because they receive enough financial aid, through Pell Grants or New York Tuition Assistance grants, to cover tuition, will not receive any funding from the Excelsior Scholarship. This is problematic, as the Scholarship targets students from middle income families, instead of helping students from lower income families who struggle to pay for living expenses, books, and transportation even though they may not be paying out-of-pocket for tuition. Additionally, in order to be eligible for the Excelsior Scholarship students must enroll in 30 credits per year, therefore excluding part-time students.

Added to New York’s law at the last minute, just before it was signed, was a clause that turns the scholarship into a loan if the student leaves the state within four years of graduating (assuming they received four years worth of funding). This subsidy-turned-loan is problematic for many reasons. It both impedes the ability to work in the national labor market, as well as could incentivize unemployed graduates to stay in New York rather than leave the state to find a job elsewhere. Additionally, the converted subsidy-turned-loan would not have the same benefits as a federal student loan, like the income-based repayment arrangement.

Some of New York State’s public officials were not thrilled with the plan. New York State Assembly Republican Leader Brian Kolb stated “Governor Cuomo isn’t providing ‘free’ tuition, he’s simply telling New York taxpayers to write a bigger check.” Other Republican lawmakers criticized the Governor’s proposal during budget negotiations for excluding students at private colleges. Additionally, while SUNY Chairman Carl McCall and Chancellor Nancy Zimpher “applauded the budget deal” and called it “truly ground-breaking,” they also had “hoped for additional support,” specifically for SUNY community colleges.

With this program, New York joins other states and cities in providing free college. Tennessee, Oregon, and San Francisco have recently made tuition free at community colleges for all residents, regardless of income. Additionally, Rhode Island is now considering a proposal that would make two years at public colleges tuition-free. Unlike the Excelsior Scholarship in New York, the proposal in Rhode Island would allow every Rhode Island resident who graduates high school in-state to be eligible for two-years free tuition at the University of Rhode Island, Rhode Island College, and the Community College of Rhode Island, regardless of income. Interestingly, the Rhode Island proposal makes it so the scholarship could only be used for a students’ junior and senior years at four-year colleges. Projections from the Rhode Island Governor’s office expect that the program would benefit 8,000 students and cost $30 million a year, less than 0.5% of the state’s budget. The proposed plan, a “last dollar” scholarship, would “cover the gap a student has on their tuition bill after using up any federal or state grants he or she already receives.”

Additionally, college tuition has been a topic on the federal level. President Trump has proposed cutting $5 billion in higher-education for lower-income Americans. Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, along with Representative Keith Ellison and other members of Congress, introduced the College for All Act, with the hope to eliminate tuition and fees at public four-year colleges and universities for students whose families make under $125,000 per year. The bill proposes that the federal government would pay 67% of tuition subsidies at public colleges and universities, and state and tribal governments would pay the other third. While the bill likely will not pass with a Republican Congress and Trump in the White House, it has been backed by the United States Students Association, the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Education Association.

While these college tuition subsidies could be extremely beneficial in allowing more students to attend college who previously could not afford it, there are many controversial issues in the scholarship plans. Who ends up paying for the scholarship? Does college truly prepare graduates for the workforce? And lastly, with all the strings-attached to New York State’s Excelsior Scholarship, can it be said that there is such a thing as free college?

At Last: New York Remembers the Adolescence of its Juveniles Offenders

On April 10th of this year, New York became the 49th state to pass legislation ending the treatment of 16 and 17 year olds as adults in the criminal justice system. Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie touted the bill’s passage as a “tremendous victory for communities across the state that have endured senseless tragedies and called on the Legislature to deliver a justice system that recognizes the difference between a child and an adult.” While New York was one of only two states to continue to prosecute these juveniles as adults, the Assembly had been working to pass similar legislation for over 12 years.

The prosecution of juveniles in adult criminal court has been proven to have serious lifelong consequences. The human brain is not fully developed until the age of 25, before juveniles mature they often lack impulse control and the ability to anticipate and understand the consequences of their actions. Adolescents tend to be receptive to interventions, responding well to juvenile treatment and services by learning to make responsible choices and ending delinquent behavior. Studies show that youth offenders prosecuted and sentenced in the adult criminal justice system are 34% more likely to be re-arrested than juveniles who are charged in the youth justice system. In addition to the impact that the adult criminal justice system has on the juvenile’s future behavior, youth offenders detained in adult prisons are more likely to be beaten by staff, sexually assaulted, 50% more likely to be attacked with a weapon, and are 36 times more likely to commit suicide while detained.

New York’s Raise the Age bill has multiple facets. Under the new legislation, 16 and 17 year olds accused of misdemeanors will be sent to Family Court. Felony cases, however, will remain in adult criminal court in a new section called the “youth part,” which will house judges trained in Family Court law. After 30 days, 16 and 17 year olds charged with nonviolent felonies will be sent to Family Court unless a district attorney has proven that there are “extraordinary circumstances” that warrant the juvenile’s retention in the adult criminal system. The term “extraordinary circumstances” is undefined in the new law, although Alphonso David, the governor’s counsel, has stated his belief that it will be widely understood to mean “remarkable, exceptional, amazing, astounding, incredible.” Those juveniles charged with violent felonies may also be transferred to Family Court if they pass a three-part test. The test balances whether the victim sustained significant physical injury, the accused used a weapon, and whether the perpetrator engaged in criminal sexual conduct.

The bill also changes the rules regarding the detention of juveniles. After the horrible details surrounding the arrest and detention of Kalief Browder became public knowledge, there was a powerful push for juvenile detention reform. Kalief Browder was a 16-year-old kid living in the Bronx in 2010 when he was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack. Mr. Browder never faltered in his denial of guilt, despite this he was detained on Rikers Island for 3 years, two of which were spent in solitary confinement, without charges. The time spent on Rikers, replete with assaults by guards and inmates, solitary confinement, and awaiting a trial that never came affected his mental state in ways that would be expected of anyone, let alone a teenager. Two years after his release from Rikers Island, Mr. Browder committed suicide and became a household name reflecting the horrors of the criminal justice system for the youth of New York. The Raise the Age legislation, signed by Governor Cuomo with Kalief Browder’s brother, Akeem, looking on, is an attempt to prevent a tragedy such as this from ever occurring again. Beginning October 1st, 2018, offenders under 18 will no longer be held at Rikers Island and those 17 years old will no longer be held in county jails, a similar rule will be enforced for those under 18 a year later.

Despite victory for proponents of the bill, many are disappointed in the newly passed legislation. Last year alone, 3,445 juveniles were charged with violent felonies and therefore would still have been prosecuted in the “youth part” of the adult criminal system. Those adolescents will continue to receive lengthy prison stays and lifetime criminal records. Kevin Parker, a State Senator from Brooklyn, voiced his consternation at how complicated this bill became, “[a]ll we had to simply do is say that we’re going to take 16- and 17-year-olds and we’re going to treat them just like 15-year-olds. That’s all we had to do, right? All we had to do. And we messed that up.”

While New York’s bill may not be perfect, it will give many young offenders an opportunity to learn from their mistakes and become law-abiding adults. Over 17,000 adolescents aged 16 and 17 are accused of misdemeanors each year, under the new bill these charges will be heard in family court where judges are trained to know what is best for the adolescent offender and have more access to social services that may help rehabilitate rather than strictly penalize this vulnerable community. The change in detention facility alone will mean the difference between a mistake and lifetime behavior for many, for some it will mean the difference between life and death. A staunch supporter of the original bill, Senator Diane Savino of Staten Island, made it clear that the fight to raise the age for adult criminal liability is far from over. “For those who don’t think it goes far enough, I will remind you: We are not dropping off the end of the earth tonight. Laws are made to amend them.”

Alexandra Raymond is from Vergennes, Vermont and graduated from New York University in 2014 with a B.A. in Sociology and Law & Society. She is expected to earn her Juris Doctor from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Alexandra will be working for an investment management firm in Boston during the summer of 2017 and will then spend her next semester studying international law at Leiden Law School in the Netherlands. Upon graduation, Alexandra hopes to pursue a career that allows her to explore her interests in business, social justice, and international law.

Alexandra Raymond is from Vergennes, Vermont and graduated from New York University in 2014 with a B.A. in Sociology and Law & Society. She is expected to earn her Juris Doctor from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Alexandra will be working for an investment management firm in Boston during the summer of 2017 and will then spend her next semester studying international law at Leiden Law School in the Netherlands. Upon graduation, Alexandra hopes to pursue a career that allows her to explore her interests in business, social justice, and international law.

The Orphan Drug Act: Unintended Consequences From Salami Slicing

Prescription drug prices are a top cause of increasing U.S. health care costs, with specialty drugs (such as Sovaldi) especially being the culprit for impacting cost trends. Even though specialty drugs constitute less than 1 percent of the total prescriptions, they account for 35 percent of the projected drug cost trend for 2017. This is a 10-percentage point increase from 2015, when specialty drugs accounted for 25 percent of the projected drug cost trends. In particular, patients, insurance companies, and providers have been closely scrutinizing orphan drugs (pharmaceuticals that target rare diseases and disorders) based on their soaring profitability and recent media exposure. According to EvaluatePharma’s 2015 drug report, 2014’s top selling orphan drug in the U.S. had sales of over $3.65 billion, amounting to $54,780 of average revenue per patient. The average orphan drug costs $111,820, which is over four times pricier than the mainstream drug cost of $23,331. This begs the question – how did orphan drugs become one of the fastest-growing products in the pharmaceutical industry?

The 1983 Orphan Drug Act incentivized pharmaceutical companies to invest and manufacture new drugs  to treat rare or orphan diseases. Historically, pharmaceutical manufacturers did not produce drugs for small patient populations. Over forty years later, the Act has stimulated life-saving treatments for over 25-30 million Americans who suffer from an estimated 7,000 rare diseases, according to the National Institutes of Health.

to treat rare or orphan diseases. Historically, pharmaceutical manufacturers did not produce drugs for small patient populations. Over forty years later, the Act has stimulated life-saving treatments for over 25-30 million Americans who suffer from an estimated 7,000 rare diseases, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The FDA established the Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD) to facilitate the evaluation of developing orphan products through the Orphan Drug Designation program. This program grants special status (orphan designation) to orphan drugs and biologics, which are defined as those aiming to treat diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. For a drug to achieve the orphan designation status, both the drug and the rare disease treated must meet certain requirements listed under 21 CFR §316.20 and 316.21. These rare diseases include genetic disorders such as Gaucher disease, cystic fibrosis, certain pediatric cancers, and follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The OOPD utilizes both “push” and “pull” incentives to promote product development. The “push” includes grants to subsidize clinical research costs, tax breaks on clinical research costs, and waivers of expensive marketing application fees. The “pull” incentives include market exclusivity for a seven-year period that is broader than for non-orphan drugs; during the exclusivity period, the FDA cannot approve a manufacturer’s application for the same orphan drug as a different manufacturer. However, if a competitor manufacturer demonstrates that their clinical uses of the same orphan drug is superior to that of the original version, the new version is not deemed as the “same drug,” in accordance with CFR 316.3(b)(13)(i),(ii). Orphan drug patent and market exclusivity adds up approximately 0.8 years more protection against pharmaceutical competition, compared to normal patent exclusivity protections. As such, the combination of broader exclusivity, small patient populations, and higher expected profits have played out favorably for orphan drug manufacturers because they can charge astronomical prices on their products.

These “push” and “pull” incentives, however, can often lead to manipulation by pharmaceutical companies in an effort to maximize profits and extend their monopolies. According to a recent six-month Kaiser Health News Investigation, a third of orphan drugs approved by the OOPD have been “either for repurposed mass market drugs or drugs that received multiple orphan approvals.” A 2015 commentary from the American Journal of Clinical Oncology reported that these loopholes have resulted in abuses of the patent system, where “[t]he industry has been gaming the system by slicing and dicing indications so that drugs qualify for lucrative orphan status benefits.” This so-called “salami slicing” technique occurs when mass market drugs, not deemed “true orphans,” are being repurposed towards treating small patient populations in an effort to attain additional FDA approval. As such, despite the many successes of the Orphan Drug Act, critics are calling for reforms to close loopholes and address escalating prices.

These “push” and “pull” incentives, however, can often lead to manipulation by pharmaceutical companies in an effort to maximize profits and extend their monopolies. According to a recent six-month Kaiser Health News Investigation, a third of orphan drugs approved by the OOPD have been “either for repurposed mass market drugs or drugs that received multiple orphan approvals.” A 2015 commentary from the American Journal of Clinical Oncology reported that these loopholes have resulted in abuses of the patent system, where “[t]he industry has been gaming the system by slicing and dicing indications so that drugs qualify for lucrative orphan status benefits.” This so-called “salami slicing” technique occurs when mass market drugs, not deemed “true orphans,” are being repurposed towards treating small patient populations in an effort to attain additional FDA approval. As such, despite the many successes of the Orphan Drug Act, critics are calling for reforms to close loopholes and address escalating prices.

According to Martin Makary, the study’s author and Professor of Surgery at John Hopkins, funding support that was originally designed for rare disease drugs are now being funneled towards blockbuster drug developments. Off label uses result in drug price inflation that often leads to higher health insurance premiums. Take rituximab, for example, the top-seller orphan drug of 2014, which was originally approved for the treatment of follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Although the disease affects about 14,000 patients per year, the drug was repurposed to additionally treat rheumatoid arthritis, a more prevalent disease that afflicts over 1.3 million patients. As such, the authors of the 2015 commentary proposed pricing negotiations and implementing clauses to reduce the exclusivity period. These could serve as checks on certain drug products that have exceeded past treating 200,000 people, the Orphan Drug Act’s threshold.

Former Rep. Henry Waxman, co-sponsor for the monumental Hatch-Waxman Act and proponent of the Orphan Drugs Act, had suggested amending the Act back in the 1990s, but those and subsequent efforts at reform have failed. According to Rep. Waxman, “Orphan drugs are orphans no more; they’re very popular. [But], there are pharmaceutical companies that handle their whole business plan to make sure their drug can be categorized as an orphan drug.” His statement sums up the ongoing dilemma and atmosphere of the drug market price gouging.

On February 3, 2017, however, Sen. Chuck Grassley, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, wrote that he had opened an inquiry on the potential manipulation of the Orphan Drug Act. Sen. Grassley states that he has already contacted staff members of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee to determine whether the Act’s incentives are truly benefiting the patients it intends to protect. In March 2017, Senators Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), and Tom Cotton (R-Ark) sent a letter to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, asking for an investigation into this matter. The Senators raised the possibility that regulatory or legislative changes might be needed "to preserve the intent of this vital law;" giving drug makers incentives to develop drugs for rare diseases.

Amidst federal regulation, several states have been pushing legislation on the monitoring and management of general prescription drug costs. For instance, Vermont recently enacted Act 165, Pharmaceutical Cost Transparency, which requires the state to annually identify up to 15 state purchased prescription drugs on which significant health care dollars have been spent, as well as require drug manufacturers to disclose wholesale acquisition costs. Other states, such as Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New York, have proposed bills with similar disclosure requirements. As such, the current trend towards drug price transparency legislation could provide potential solutions towards curtailing the escalating orphan drug pricings.

With the recent state legislative proposals and a potentially informative Senate inquiry, the spotlight remains on drug manufacturers to explain their salami-slicing, repurposing tactics on orphan designation.

Monica Chou will graduate from Boston University School of Law in 2018 and hopes to practice Health Law.

Monica Chou will graduate from Boston University School of Law in 2018 and hopes to practice Health Law.

Continuing Responses to 9/11: The Price of Justice

On September 28th, 2016 Congress voted in favor of the first veto override during Obama’s presidency. The bill at issue was the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), a very controversial piece of legislation that received massive support in both the House and Senate but was adamantly opposed to by the Administration. Prior to JASTA becoming law, victims of terror attacks and their families could only bring suit against a foreign nation if the U.S. Department of State had designated that nation as a state sponsor of terrorism and the specific attack was aided by the government. Currently, there are only three nations subject to lawsuits as state sponsors of terrorism: Iran, Sudan, and Syria. JASTA severely limits the scope of sovereign immunity and expands the liability of foreign nations for terrorist attacks.

Under JASTA, United States federal courts will now have jurisdiction over civil matters that are brought by United States citizens against foreign nations for claims of injury to person or property that occur inside of the United States as a result of either (1) an intentional act of terrorism or (2) a tortious act by a foreign state, or any official of that foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her office regardless of where the act occurred. The bill also imposes liability on any person who conspires to commit or knowingly aids and abets an act of international terrorism committed by a designated terrorist organization. While JASTA does authorize the Department of Justice to grant a stay if the United States is engaged in good-faith discussions with the foreign nation to resolve the claims, former President Obama was concerned by the serious potential consequences of the bill.

Under JASTA, United States federal courts will now have jurisdiction over civil matters that are brought by United States citizens against foreign nations for claims of injury to person or property that occur inside of the United States as a result of either (1) an intentional act of terrorism or (2) a tortious act by a foreign state, or any official of that foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her office regardless of where the act occurred. The bill also imposes liability on any person who conspires to commit or knowingly aids and abets an act of international terrorism committed by a designated terrorist organization. While JASTA does authorize the Department of Justice to grant a stay if the United States is engaged in good-faith discussions with the foreign nation to resolve the claims, former President Obama was concerned by the serious potential consequences of the bill.

The first of these concerns was that such a bill will reduce the effectiveness of a United States response to an indication that a foreign state has supported acts of terrorism. Litigation brought under this act will effectively remove the matter from the hands of national security and foreign policy professionals and place these consequential foreign affairs decisions in the hands of private litigants. In these matters, the President is meant to be the sole representative of the United States to give a strong unified voice for the nation. If a foreign state acted in a way so as to provide support to terrorist organizations which were harming United States citizens, then a unified response by the United States designating that nation as a state sponsor of terrorism would be warranted and would carry many more consequences than being sued under this new law.

The most obvious effect of JASTA, and the driving force behind the creation of this legislation, is to allow the victims of the September 11th attacks to bring suit against the government of Saudi Arabia, a country that some believe supported the terrorist organization responsible. The reason for this belief stems from the fact that fifteen of the nineteen September 11th hijackers were Saudi citizens, although neither the 9/11 Commission Report or the 2014 FBI Report on the Commission and new findings found any connection to the government of Saudi Arabia. The United States has an ongoing relationship with the Kingdom and the revocation of sovereign immunity will result in strained and potentially hostile relations in the future. Before the bill was passed, the foreign minister of Saudi Arabia, Adel al-Jubeir, warned that if JASTA was passed, the Kingdom would sell off approximately $750 billion held in United States treasury securities and other assets to avoid having it seized by American courts. Such an action could have drastic destabilizing effects in the global financial market but could also be equally as detrimental to Saudi Arabia. For this reason, it is unlikely that they will follow through with this threat since continued cooperation is needed by both nations. Some scholars believe that a more probable act of retaliation will come in the counterterrorism field, opening Americans up to greater physical danger.

The second concern raised by former President Obama was the high likelihood of reciprocal laws being enacted by other nations. The United States is the largest beneficiary of sovereign immunity since it has a greater international presence than any other nation. Revoking the sovereign immunity of other countries will undoubtedly lead to similar actions by foreign nations toward the United States, subjecting the nation to foreign court proceedings. The end of internationally recognized and respected sovereign immunity in these cases will result in suits against the United States which could lead to government assets being seized abroad, a particularly attractive idea for foreign nations given the United States’s financial backing. This concern was somewhat validated when French Parliament member, Pierre Lellouche, said that he would pursue legislation allowing French citizens to bring lawsuits against the United States for cause after the passage of JASTA.

The third concern raised was the potential for complicating the United States’ relationships with one of our closest of allies. Allowing litigation by United States citizens to be brought against our allied nations could enable wide-ranging discovery demands, which could lead to a breakdown in the amount of cooperation the United States receives in the future. A very possible response is the foreign nation limiting their cooperation on national security issues at a time when the United States needs to be building and strengthening alliances more than ever.

Just two days after JASTA became law, the first lawsuit was filed in Washington D.C. Stephanie Ross DeSimone alleged that the Saudi Arabian government provided material support to al Qaida and its leader, Osama bin Laden, resulting in the September 11th terrorist attack that killed her husband. In addition to Ms. DeSimone, the new law will allow approximately 9,000 potential plaintiffs to sue Saudi Arabia for injuries related to the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001.

While the House and Senate approved this bill with a large majority, a fact that former President Obama believed resulted from a desire not to vote against a 9/11 bill so soon before an election, several members of Congress have already begun to voice concern about the unintended consequences of the legislation. While no firm plans have been laid down, there has been talk in Congress of the need for further discussion on the matter and potential amendments to the new bill to address some of the newly recognized potential consequences. With the prevalence of terror attacks in today’s society and the speed with which lawsuits are being filed, there is no doubt that if Congress hopes to prevent any of the unintended consequences from being realized they must act quickly.

The unintended consequences of this bill began to arise almost immediately. Anti-Israel activists have already begun using JASTA to sue the Israeli government, claiming that it has committed war crimes, genocide, and ethnic cleansing against Arabs living in the West Bank. The complaint argues that “[b]y promoting, participating in, or funding international terrorism, all defendants have also violated the recently enacted statute known as Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorist Act.” Several individuals recently appointed to President Trump’s administration are singled out by these claims. The complaint alleges that David Friedman, a lawyer chosen by President Trump as U.S. ambassador to Israel, sends $2.2 million to settlers of Bet El every year and has funded Israeli settlements since 1977. Friedman is also president of American Friends of Bet El Institutions, a co-defendant in this action. The Kushner Family Foundation is yet another defendant with close ties to the Trump administration that is claimed to have violated federal law. This claim is merely the beginning of similar actions taken against foreign nations under the broad scope of JASTA.

There have been some reports that Saudi Arabia was using an intermediary named Qorvis to deceive United States veterans and convince them to lobby for an amendment to JASTA that would limit the scope of liability to those nations that “knowingly” support terrorist organizations. These claims have spread through many lesser known news sources but remain unsubstantiated and have gone unmentioned among mainstream media. It does not appear that Saudi Arabia has taken any action in response to the passing of JASTA at this point despite the numerous threats.

The Wall Street Journal reported last March that Saudi Arabia’s energy minister Khalid al-Falih said his government was “not happy” about the law, but believes that after “due consideration by the new Congress and the new administration, that corrective measures will be taken.” Whether the Trump Administration will have more influence over Congress than the Obama Administration on this issue is a significant foreign policy question.

Alexandra Raymond is from Vergennes, Vermont and graduated from New York University in 2014 with a B.A. in Sociology and Law & Society. She is expected to earn her Juris Doctor from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Alexandra will be working for an investment management firm in Boston during the summer of 2017 and will then spend her next semester studying international law at Leiden Law School in the Netherlands. Upon graduation, Alexandra hopes to pursue a career that allows her to explore her interests in business, social justice, and international law.

Alexandra Raymond is from Vergennes, Vermont and graduated from New York University in 2014 with a B.A. in Sociology and Law & Society. She is expected to earn her Juris Doctor from Boston University School of Law in 2018. Alexandra will be working for an investment management firm in Boston during the summer of 2017 and will then spend her next semester studying international law at Leiden Law School in the Netherlands. Upon graduation, Alexandra hopes to pursue a career that allows her to explore her interests in business, social justice, and international law.

Will New “Real World Evidence” Standard Hurt Drug Safety?

On December 13, 2016, President Barack Obama signed the 21st Century Cures Act into law. The Act passed the House and the Senate with considerable bipartisan support, a rarity in today’s political climate. The Act is a sprawling piece of legislation, covering many health care policy areas and appropriating billions of dollars for various causes, research, and organizations. The main focus of the legislation aims to fund three key initiatives: former Vice President Joe Biden’s “cancer moonshot,” the BRAIN Initiative (a project designed to learn how the brain works on a more complete level); and the Precision Medicine Initiative (a venture to increase the availability of genetic data and streamline its use). The 21st Century Cures Act devotes nearly $4.8 billion to these projects alone. Other appropriations include funding to help states combat the ongoing opioid epidemic and reinforcements for the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). The Act passed largely due to an incredible lobbying effort. More than 1,455 lobbyists representing over 400 organizations advocated for or against the law. The Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America (“PhRMA”), the pharmaceutical industry trade federation, spent more than $24 million on lobbying related to the legislation. The 21st Century Cures Act is a piece of omnibus legislation that has far-reaching implications in the health care field. Despite the Act’s noteworthy bipartisan support, there are a number of vocal opponents to the legislation. Most of the concerns stemming from the legislation focus on the provisions related to the Food and Drug Administration's approval of new drugs.

One notable provision (§3022, p.165) of the 21st Century Cures Act that has been the subject of some controversy involves the use of Real World Evidence (“RWE”). The Act defines RWE vaguely (§3022(b), p. 165), only providing the following: “data regarding the usage, or the potential benefits or risks, of a drug derived from sources other than randomized clinical trials.” The Act requires the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to develop a program for evaluating the use of real world evidence (“RWE”). Per the Act (§3022(a)(1-2), p. 165), RWE will now be used to support new indications for drugs already on the market and to fulfill post-marketing study requirements. While many are optimistic that this provision will assist the FDA in improving the efficiency of the drug approval process, others are concerned about the impact RWE will have on the safety and efficacy of newly approved medications.

Over the past decade, the FDA has trended towards embracing post-market data. This trend is reflected by

the substantial increase in use of expedited approval pathways. The FDA employs four expedited approval pathways: Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review. A pharmaceutical company must apply for each designation separately, but a single drug may qualify for multiple pathways. The pathways vary but all promote the same goal: “treating serious conditions” or “fill[ing] an unmet medical need.” Through expedited approval pathways, FDA effectively pushes drugs to market by shortening application review periods, allowing surrogate endpoint clinical trials, and increasing post-market data reliance. These “shortcuts” increase the number of available drugs with incomplete safety and efficacy profiles by reducing the amount of clinical trial-generated data needed for approval. Expedited pathways favor therapy availability over absolute safety. In 2015, the Government Accountability Office found (p. 21) that from 2006 to 2014, 49% of approved new molecular entities utilized at least 1 expedited pathway. The Report also concluded (p. 18) that FDA reviewed a drug using at least 1 expedited approval pathway in approximately 8.6 months, compared to approximately 12.1 months for drugs without a pathway. As such, expedited approval pathways, supposed to represent an exception for drugs, have practically become the norm.

Coinciding with this rise has been a rise in reported adverse drug reactions (“ADRs” or “adverse events”) from prescription drugs. The fact that the rise in reliance on these pathways mirrors the rise in ADR reports suggests a correlation. Mary K. Olson, a professor of economics at Tulane University, examined data on drug approvals from 1990-2001 to determine if there is a direct relationship between expedited approval pathways and adverse events. Olson determined (p.197) that a 2-month reduction in review time results in a 21-23% increase in serious adverse events and a 19-21% increase in adverse event-related deaths and concluded “there is a trade-off between review speed and drug safety.”

Despite the statistics showing a trend toward faster drug approval coinciding with a rise in pharmaceutical-related injuries, speeding up the FDA drug review process remains a focal point in the political landscape. Patient pressure constitutes the strongest driver of shorter review times. Patient advocacy groups publicly campaign for wider access to experimental drugs. These groups reason that patients will accept the risk of side effects in exchange for the hope provided by a new therapy. Public support also directly affects review times. A study (p. 59) determined that media coverage and the wealth of patient advocacy groups have a direct relationship with review times. According to the study, in a vacuum, a one standard deviation increase in Washington Post articles on a disease or patient advocacy groups reduces review by 4 to 8 months. Advocacy group wealth has a similar effect: “marginal differences” in resources translates to a 3.5 to 7 month reduction in review time. Accordingly, the 21st Century Cures Act constitutes a decisive victory for patient advocacy groups. The legislation intends to streamline the drug approval process, most notably with the introduction of Real World Evidence.

There are a number of clear issues with the use of Real World Evidence. Under the Act, RWE can come in the form of summary data, departing from the fully recorded and itemized clinical trial data currently used for drug approvals. The FDA admits that RWE may be useful for drug approval, but most sources of such data are not designed to meet regulatory requirements. Legislators and the FDA intend for RWE to encompass data such as FitBit readings, which produce data that do not meet the standards governing clinical trials. As such, despite the potential for beneficial use of RWE, the idea is fraught with complications.

Understandably, critics fear the incorporation and use of RWE poses a threat to the integrity of the drug approval process. This provision of the 21st Century Cures Act has the potential to lead to public policy built on misinformation. However, the use of real world evidence could greatly speed the drug approval process and deliver much-needed new medicines to sick and dying Americans. It remains to be seen what the long-term impact of this legislation will be, but it is an area worth monitoring.

Nicholaas Honig is from Collegeville, Pennsylvania and graduated cum laude from Hobart and William Smith Colleges, where he majored in Political Science. Nicholaas is expected to graduate with a concentration in health law from the Boston University School of Law in spring 2018. Post-graduation, Nicholaas hopes to work in the field of pharmaceutical regulatory law.

Nicholaas Honig is from Collegeville, Pennsylvania and graduated cum laude from Hobart and William Smith Colleges, where he majored in Political Science. Nicholaas is expected to graduate with a concentration in health law from the Boston University School of Law in spring 2018. Post-graduation, Nicholaas hopes to work in the field of pharmaceutical regulatory law.

The Role of the Courtroom in Combating Domestic Violence

The rhetoric surrounding the courtroom can be idealistic. The courtroom is supposed to be a symbol of justice, where every party has a fair opportunity to be heard. Yet the reality for survivors of domestic violence is far from this ideal. Survivors who have the strength to seek their day in court have already shown an incredible amount of strength and courage. They should be met with hope, encouragement, and assistance. But this is a goal yet to be achieved.

Survivors often feel unsafe walking into the courtroom. Not only are survivors at more risk after leaving their abuser, “[a]busers also use court appearances as opportunities to stalk and maintain contact with their ex-partners.” Survivors face an uphill battle in the courtroom. As Sara Ainsworth of Legal Voice stated, “[t]here's an enormous bias against anyone making accusations [of abuse].”

Domestic violence survivors may end up in the courtroom for a variety of reasons, including seeking a protective order and child custody proceedings. Current law in Massachusetts governing domestic violence in custody proceedings falls far short of the protection society owes to survivors. First, the definition of abuse is narrow, only encompassing physical abuse. Specifically, Massachusetts General Laws Section 31A defines abuse as “(a) attempting to cause or causing bodily injury; or (b) placing another in reasonable fear of imminent bodily injury.” The statute further states that either a pattern of abuse or a ‘serious incident’ of abuse (defined as “(a) attempting to cause or causing serious bodily injury; (b) placing another in reasonable fear of imminent serious bodily injury; or (c) causing another to engage involuntarily in sexual relations by force, threat or duress”), triggers a rebuttable presumption that granting the abuser sole or shared custody is not in the best interest of the child. The presumption is triggered by a preponderance of the evidence, and can be rebutted by a preponderance of the evidence. A past or current protective order does not automatically trigger the presumption.

Further, while the facts that brought about a protective order can be admissible, protective orders themselves cannot be admitted as evidence of abuse. This means that even if a survivor has succeeded in protecting herself and her child(ren) by obtaining a protective order, she will not automatically get custody of her children. She will have to face her abuser again in the courtroom, and will have to prove once again that abuse has occurred. Further, even if there was extensive verbal, emotional, and psychological abuse, the presumption against custody will not be triggered.

In addition to dealing with statutes that do not adequately protect them, survivors must also deal with judges who may not understand their experiences. In fact, women who are seeking protection for themselves and their children from an abuser are often met by similar behavior from judges. Domestic abuse is often described with what is termed the ‘Power and Control Wheel.’ The wheel describes that variety of ways abusers use their power to manipulate and control their victims. The Texas Council on Family Violence created a power and control wheel that describes the ways judges also reinforce women’s entrapment.

The role of the court in protecting domestic survivors must extend beyond equitable orders. It is an unfortunate truth that sexism is still a very real reality in the courtroom. Moreover, many judges do not understand the dynamics of domestic violence, and do not handle custody disputes with the appropriate sensitivity to domestic abuse, even if they are statutorily required to do so. Judges have the opportunity to empower victims, or to make them feel even less in control.

The idea that judges can play a positive role in protecting domestic abuse survivors is not new. In 1999, The Northeastern University Press published an article titled “Battered Women in the Courtroom: The Power of Judicial Responses.” The article lists multiple ways judges can support survivors: supportive judicial demeanor; take the violence seriously; make the court hospitable; prioritize women’s safety; address the economic aspects of battering; focus on the needs of children; enforce orders and impose sanctions on violent men; and connect women with resources. Specific recommendations targeted sexism during proceedings, including “refusing to joke and bond with violent men”; “talking with battered women rather than around them”; “correcting institutional bias in favor of men”; and “eschewing bureaucratic/perfunctory or hostile attitudes toward victims and casual or collusive attitudes with batterers.”

The article identified five types of judicial demeanor in hearings for protective orders: 1) good-natured; 2) bureaucratic; 3) firm or formal; 4) condescending; and 5) harsh. Interestingly, “[t]here types . . . were demonstrated toward violent men[:] [f]irm or formal, bureaucratic and good-natured. Most judges were good-natured with women and firm with violent men. Condescending and harsh demeanor was not directed toward violent men.” (emphasis added). There is no excuse for the gender discrimination revealed by this study.

While this study is dated, women still face judges who are hostile toward domestic violence survivors. Judges can make a difference by understanding that survivors can be overwhelmed in the courtroom; ensuring a the record is comprehensive; not blaming the victim; and having zero tolerance for violence and gender discrimination during proceedings.

Judges can be powerful role models by choosing to treat women with respect and taking the humble approach of recognizing their need to learn the dynamics of domestic abuse in order to be effective judges.

Boston University School of Law, class of 2018