Category: Analysis

Florida Says “Sorry” to the Groveland Four, But Is an Apology Enough?

In April 2017, the Florida legislature passed a resolution (HCR 631) formally apologizing for the unjust prosecution and persecution of the “Groveland Four”, and calling for their exoneration by Governor Rick Scott. The “Groveland Four” is the popularized moniker for Charles Greenlee, Walter Irvin, Samuel Shepherd, and Ernest Thomas; four young black males (age 16 and up) accused of raping a 17-year-old white woman in Groveland, 1948. The infamous case took place during the Jim Crow era, following generations of wrongfully accused, wrongfully prosecuted, wrongfully convicted, and wrongfully executed black citizens. Shortly after they were accused of the crime, Samuel Shepard and Walter Irvin, both World War II veterans, were abducted by law enforcement officers and taken to a secluded spot to be beaten and tortured. After this assault, the deputy officer took Shepard and Irvin to the scene of the crime, only to find that their shoes did not match the footprints that allegedly belonged to the true assailants. Frustrated, the officers took Shepard and Irvin to an interrogation room where they were beaten and tortured until they confessed.

Eventually, Charles Greenlee was picked up by the authorities and subjected to the same treatment a

Shepard and Irvin, but Ernest Thomas caught wind of the investigation and attempted to flee. Thomas’s flight incited a lynch mob, led by both the local sheriff’s department as well as the Ku Klux Klan. The mob not only hunted down and killed Thomas over 200 miles away, but also terrorized the black, segregated section of Groveland, burning down the suspects’ houses and causing numerous black residents to abandon the city in fear. Sheriff Willis McCall, though complicit in stirring up some of chaos, attempted restoring a semblance of order by having the remaining suspects moved from the local jail to the state prison to await trial. The NAACP and the FBI got involved with the case as national attention grew. After documenting the beatings and torture by local law enforcement, the FBI recommended that the Tampa U.S. Attorney General bring charges, but no indictments were made. Franklin Williams of the NAACP represented the remaining suspects, and through his own investigation, suspected the rape accusation was actually a cover-up of a domestic violence incident between the accuser and her boyfriend. During the trial, there was evidence that the suspects had not been in town during the incident and that the footprint (which never matched the suspects’ shoes) was fabricated by the deputy. Still, an all-white jury found Shepard, Irvin, and Greenlee guilty within minutes of deliberating, sentencing Shepard and Irvin to death, and 16-year-old Greenlee to life in prison.

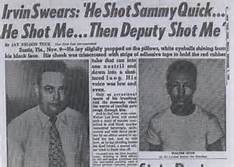

The United States Supreme Court overturned the capital convictions (Greenlee never appealed) and remanded the case for retrial. Sheriff McCall was transferring Shepard and Irvin back to Lake County (Groveland’s county) for the trial, when McCall claimed he was attacked by the two black men and forced to shoot them in self-defense. Fortunately, Irvin survived the multiple gunshots and told his version of events, which included an unprovoked execution of Shepard and collusion between McCall and his deputy to cover up the failed execution of Irvin. At the retrial, eventual first black Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall represented Irvin, but faced problems similar to the first trial, and Irvin was sentenced to death again. The Florida governor spared Irvin and commuted his sentence to life in prison; Irvin went on to spend 14 years in prison and was released in 1968. He fled Florida for Tennessee, but came to visit Lake County in 1970, where he was found dead in his car. Greenlee was eventually released.

The United States Supreme Court overturned the capital convictions (Greenlee never appealed) and remanded the case for retrial. Sheriff McCall was transferring Shepard and Irvin back to Lake County (Groveland’s county) for the trial, when McCall claimed he was attacked by the two black men and forced to shoot them in self-defense. Fortunately, Irvin survived the multiple gunshots and told his version of events, which included an unprovoked execution of Shepard and collusion between McCall and his deputy to cover up the failed execution of Irvin. At the retrial, eventual first black Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall represented Irvin, but faced problems similar to the first trial, and Irvin was sentenced to death again. The Florida governor spared Irvin and commuted his sentence to life in prison; Irvin went on to spend 14 years in prison and was released in 1968. He fled Florida for Tennessee, but came to visit Lake County in 1970, where he was found dead in his car. Greenlee was eventually released.

The terrible saga of the Groveland Four is only a snippet of the corruption and racism that plagued Lake County, Florida, and the criminal justice system as a whole during and after Jim Crow. Still, this recent formal apology only follows after mounting public pressure to acknowledges the horrendous wrongs of the state. In 2012, the same year Greenlee died, the book Devil in the Grove, which tells the story of the Groveland Four, came out. This book not only renewed interest in the case, but also won a Pulitzer Prize. The book drove a University of Florida student to launch a massive Change.org petition, and with the help of the Miami Herald and Greenlee’s daughter, the matter of an apology and exoneration finally reached a boiling point. Now that an acknowledgment and formal apology has passed the legislature, the wronged accused’s families – and history itself – await the posthumous exoneration by the governor.

If the governor eventually exonerates these innocent African Americans, after waiting over a year to do so, it would follow a growing trend of acknowledging the terrible failures of the criminal justice system and political leaders during the 20th century. However, given the quantity and severity of these failures, should leaders be taking more active steps to right these egregious wrongs, instead of simply apologizing and exonerating? While surviving family members of these victims may be gladdened by a formal acknowledgement of the truth, should they be compensated for their generational pain and suffering, lost wages, even lost earning potential? The impact of these unjust persecutions is not limited to their historical time period, nor to the victims’ families – the community, and even the whole nation, felt the repercussions of these state sanctioned racist acts. These acts also highlight glaring failures of accountability and checks and balances in the criminal justice system. Politicians score political points for acknowledging their state’s past, without taking proactive measures to prevent the same injustices in the future. Civil rights activists believe lawmakers should do more than just apologize, and instead commit resources to ensuring citizens are educated about these dark corners of history, as well as reforming law enforcement offices to ensure accountability and true justice. Others believe that the apologies are not even necessary; what happened in the past should remain there, and present-day America should not apologize for the sins of its fathers. Either way, as the nation reconciles more of these injustices, lawmakers should be thinking of ways to protect their constituents from future injustice.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Andrea Ogechi-Okoro graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

A New Exclusion from the Capital Gains Rate: Self-Created Intangibles

On December 20, 2017 Congress passed H.R. 1, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This act introduces the most sweeping tax changes in decades lowering individual and corporate tax rates, with one stated goal of allowing buyers to write off the costs of new investments. In relevant part, this Act introduces one provision that removes a favorable tax rate for innovators with self-created intellectual property and eliminates the ability to treat certain self-created intellectual property as capital assets.

Under the prior tax scheme, self-created intellectual property would have been subject to the capital gains tax rate following sale of those assets. However, Section 1221 of the Internal Revenue Code under the new law exempts self-created intellectual property from capital gains treatment.

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

“This new tax law amends IRC Section 1221(a)(3), resulting in the exclusion of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), and a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) from the definition of ‘capital asset.’ As a result of this exclusion, gains or losses from the sale or exchange of a patent, invention, model or design (whether or not patented), or a secret formula or process that is held either by the taxpayer who created the property or a taxpayer with a substituted or transferred basis from the taxpayer who created the property (or for whom the property was created) will not receive capital gains treatment.”

Effectively, the sale of self-made intellectual property typically will now be subject to the higher top individual tax rate of 37 percent, as opposed to the capital gains tax rate of 20 percent. In practice, this will dramatically alter if and how a seller chooses to dispose of these assets.

Before, sellers would be encouraged to sell self-made intellectual property; however, under the new scheme, sellers are less encouraged to sell these assets because they will be subjected to a significantly higher tax rate. Under the previous tax scheme, a partnership’s sale of assets could be eligible for the long-term capital gains rate. Under the new Act, entrepreneurs and individual inventors possessing newly designed, self-made technologies will not be eligible for the lower capital gains rate when they create a company from that technology or sell the technology to another who will create a company. To net the same amount of after-tax dollars following a sale, owners of self-created intellectual property must seek a higher purchase price to offset the higher tax treatment. In effect, the new tax scheme alters the pricing and value of a patent.

Congress’s intent regarding the capital gains tax is that profits and losses arising from everyday business operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

operations be characterized as ordinary income and loss, not capital gains. Therefore, the “self-made intangibles” exclusion is likely to be broadly construed to include most forms of intellectual property and this exclusion furthers that broad purpose. However, the practical effect of this exclusion from the capital gains tax is curious considering Congress’s goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The exclusion eliminates an incentive to sell assets, which conflicts with the legislation’s goal of allowing buyers to write off the cost of new investments. Rather than further incentivizing investment, this provision erects a significant barrier to investment. Buyers will be eager as ever to purchase assets because of immediate expensing, but sellers will be hesitant to sell.

There are a few limitations to this discussion. Section 1221’s exception of intellectual property from the capital gains tax rate will likely only have a practical effect on the behavior of individuals, rather than corporations. The difference between the capital gains rate and ordinary income is much greater for individuals than it is for corporations; the corporate tax rate under H.R. 1 is 21 percent, only a one percent increase from the capital gains rate, as opposed to a 17 percent increase between the capital gains rate and the top individual income rate. Therefore, corporations are unlikely to treat the sale of these “self-created tangibles” significantly differently than under the previous tax scheme, at most seeking a modest increase in sale price to accommodate the one percent tax increase. In addition, Section 1221(b)(3) directs that musical compositions and copyrights in musical works may still be treated as capital assets. Therefore, not all intellectual property will be affected by this categorical exclusion from capital gains.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Eric Dunbar graduated from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

States’ Efforts for Veterans Should Be Models

Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis once called America’s states “laboratories of democracy;” state legislatures can tinker with public policy and, in theory, see what works and doesn’t work. One area where these laboratories are in full swing is in the area of state-level veteran’s benefits.

Many states provide basic benefits, in addition to benefits provided at the federal level, for veterans who serve the nation honorably and meet eligibility criteria. Things like: free admission to parks, hunting and fishing licenses at low or no cost, reduced rates for education at state funded colleges and universities, tax reductions and rebates, and veteran’s preferences for hiring in state jobs, are relatively common. Some states experiment with veteran’s policy by pushing well beyond these common state programs. Texas for example, through the very generous Hazelwood Act, provides up to 150 hours of exemption from tuition for veterans at state colleges and universities, or, if the veteran doesn’t use the benefit, for their spouse or child. Quite a few states (including Massachusetts) fund veteran’s nursing homes and are working to tackle veteran’s homelessness.

All of these programs are impressive and necessary and, they couldn’t be more important. Current veteran suicide rates are staggeringly high. More than seven thousand veterans took their lives in 2014. Of those veterans 70% were not enrolled in the federal VA system. That crisis, coupled with high veteran homelessness rates, poses significant risks to veterans living on the border of, or in, poverty. States address these challenges among their veteran populations in a variety of ways, but it is the way that Massachusetts offers commonwealth veterans in need assistance that show its progressive roots. Roots that stretch back to the Civil War.

During the Civil War, Massachusetts passed Mass. General Law Chapter 115 (Chapter 115). The statute has grown since then, but it has always provided a veteran’s agent in every Commonwealth municipality and assistance with veteran burials and grave services. Today, Chapter 115 benefits still provide a veteran’s agent (now referred to as a veterans service officer or VSO) and cemetery services, but the statute also provides a comprehensive benefit that truly seeks to serve those who have served.

This benefit is probably one of the most effective income-assistance benefits in the nation. It is funded through a city/state partnership where the city’s employee, the Veteran Service Officer (certified and trained by the state Department of Veteran’s Services), uses the regulations promulgated by the state Department of Veteran’s Services (108 Code of Massachusetts Regulation) to makes a determination about the eligibility of the veteran. Initially, if a veteran is eligible for Chapter 115, the veteran’s benefit is paid from the city’s budget. This process makes the Veteran Service Officer accountable to their respective Mayors, City Mangers, and City Councils.

In addition to being accountable to the municipal leadership, when a VSO approves Chapter 115 benefits auditors at the state Department of Veteran Services also reviews the veteran’s file to ensure that eligibility criteria are met and statutory guidelines and obligations are followed. If a VSO denies chapter 115 benefits, or removes a veteran from the program for failure to comply with job searches or income reporting mandates, the veteran can appeal that decision to the state Department of Veteran’s Services (and to higher administrative courts if necessary).

Throughout the veteran’s participation in the Chapter 115 program the Veteran Service Officer has statutory obligations to help the veteran file any and all VA claims and applications for healthcare and other social safety net benefits and to ensure that veterans that are able to work are actively seeking employment and reporting their income to the VSO. Commonwealth VSOs become, throughout this process, the veteran’s advocate, mentor, and coach. Finally, at the end of the fiscal year, 75% of the Chapter 115 benefits that the city pays out are reimbursed by the state Department of Veteran’s Services.

Are Chapter 115 benefits a perfect solution to all the challenges that commonwealth veterans face? Of course not. No government program, non-profit, charity, or business can address all of the complex issues that American veterans deal with. The challenges in transitioning from service in our all-volunteer military to civilian life are serious, but they are surmountable. Examples like the Hazelwood Act and Chapter 115 benefits are just two examples of how to create a net of support for veterans. Other states should look to Texas and Massachusetts to create similar programs, while continuing to experiment.

Kenneth Meador was an Army combat medic who graduated from the University of Oklahoma and Boston University School of Law (2018). He plans to focus his legal career on helping our nation's veterans.

Kenneth Meador was an Army combat medic who graduated from the University of Oklahoma and Boston University School of Law (2018). He plans to focus his legal career on helping our nation's veterans.

Ballot Initiatives as a Fourth Branch of Government?

The Massachusetts Marijuana Legalization Initiative was a consistent conclusion to the State’s foray into cannabis regulation. Massachusetts decriminalized and legalized cannabis for medical use through ballot initiatives in 2008 and 2012, preparing the public for a controversial and protracted path towards legalization. The success of Question Four raised a multitude of familiar policy questions; what are the legal risks legalizing a federally prohibited substance, or how to entice investor confidence in a cannabis market given the Trump Administration’s regressive cannabis policy? There is also a more democratically existential question: what is the role of the voter initiative, and should this role be celebrated?

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts provides for such direct participation through four ballot initiative forms: law petitions, constitutional amendment petitions, referendum petitions, and public policy petitions. Law petitions, the mechanism most widely understood through the public, are governed by surprisingly straightforward rules. Ballot petitions begin their lives as petitions of law to be adopted by the Legislature. Massachusetts first requires a minimum of ten qualified voters to draft and sign a petition containing the full text of the proposed law for submission to the Attorney General, who returns the petition with a concise summary following confirmation that the subject of the proposal has not violated any Constitutional or procedural requirements. Petitioners then file the proposed law and summary with the Secretary of the Commonwealth, who in return provides signatory forms containing the law’s summary for the gathering of signatures. Assuming that this summary and petition form are returned without challenge, an achievement it its own right, petitioners may then move to acquire the requisite signatures, quantified as “at least . . . 3% of the total vote cast for all candidates for Governor (excluding blanks) at the last state election.”

any Constitutional or procedural requirements. Petitioners then file the proposed law and summary with the Secretary of the Commonwealth, who in return provides signatory forms containing the law’s summary for the gathering of signatures. Assuming that this summary and petition form are returned without challenge, an achievement it its own right, petitioners may then move to acquire the requisite signatures, quantified as “at least . . . 3% of the total vote cast for all candidates for Governor (excluding blanks) at the last state election.”

The ballot initiative process is not designed to circumvent the legislature – at this stage, the legislature considers the petition, without opportunity for amendment, and may ultimately vote for engrossment and delivery to the Governor for final signature. Even at this stage, the democratic power of ballot initiatives is compelling, regardless of whether enactment follows. The legislature may feel increased pressure to address the subject through independent legislation, responding to a newly recognized mandate from the public will, while avoiding the drafting and policy deficiencies sometimes associated ballot initiatives. These responses are not direct responses to the initiative petitions, however. The legislature may only take four actions: enactment, disapproval, inaction, or proposal of a substitute. Any action beside enactment returns the initiative to its petitioners, who upon gathering the requisite number of signatures, puts the question to the voters at the next state-wide election.

Democracy in Action, or a Breakdown in Lawmaking?

The utility of ballot initiatives is more than the results they may yield. Substantive results aside, the evaluation of ballot initiatives is multifaceted. First, ballot initiatives provide an opportunity to spur reactionary legislation, by presenting to legislatures with a choice between engrossing the initiative law petition themselves, pursuing independent legislative action on the matter, or rejecting the measure and resigning its fate to the public’s will.

Second, ballot initiatives provide a path for citizens to democratically express their ideas. Of course, the democratic nature of ballot initiatives says nothing of morality: initiatives range from the laudable measures calling for statewide universal healthcare to the morally insolvent represented by acts like the “Sodomite Suppression Act”, a reprehensible initiative calling for statewide execution of members of the LGBTQ community.

The range of subjects covered by ballot initiatives is nearly limitless, and while most initiatives do not survive long enough to receive a vote from the general public, ballot initiatives remain procedurally significant merely in that they are introduced into the marketplace of ideas. This procedural significance exists regardless of the substantive merits of the initiatives, with democratically compelling state ballot initiative questions like: “should we give $1 million to one random voter?”, “should Denver set up a commission to track aliens?”, and “should we stop selling the Europeans our horse meat?” Regardless of the content of the initiatives, their consideration is itself a democratic virtue and strong argument for the continued use of ballot initiatives.

Third, while ballot initiatives are democratic,they sometimes produce substantively imperfect results. Despite being the will of the people, the substantive terms of the Massachusetts Marijuana Legalization Initiative were short-lived. Towards the end of July 2017, Massachusetts Governor Baker signed into law House No. 3818, An Act to ensure safe access to marijuana. This law amended the voter approved cannabis laws by raising taxes on cannabis from 12% to 20%, altered the scheme in which municipalities could ban legal cannabis sales, and restructured the newly formed Cannabis Control Commission. As a result, although legalization advocates were able to achieve their goal of legalizing cannabis, the regulatory structure was significantly different than originally envisioned.

Ballot Initiatives: The People’s Branch of Government – Truism, or Absurdity?

The debate over the place of ballot initiatives within democracy is ongoing. On one hand, ballot initiatives can be construed as a “fourth branch of government” (or perhaps fifth, for those readers who may also delegate such status to administrative agencies).

Ballot initiatives allow citizens to circumvent special interests and legislative roadblocks to see their will materialized. Alternatively, although ballot initiatives support the free expression of ideas, they fail to provide an opportunity for consideration and compromise with dissenting views, which is substantially undemocratic. Rather than circumventing special interests, this shortcoming may make ballot initiatives the epitome of special interests, allowing the loudest voices in the room to acquire funding and support on the public sphere, regardless of their relative merits and detractors.

Ballot initiatives allow citizens to circumvent special interests and legislative roadblocks to see their will materialized. Alternatively, although ballot initiatives support the free expression of ideas, they fail to provide an opportunity for consideration and compromise with dissenting views, which is substantially undemocratic. Rather than circumventing special interests, this shortcoming may make ballot initiatives the epitome of special interests, allowing the loudest voices in the room to acquire funding and support on the public sphere, regardless of their relative merits and detractors.

The cannabis ballot initiative saga in Massachusetts presents a compromise between this dichotomy. Ballot initiative lawmaking may indeed represent a new “fourth branch of government” – but a fourth branch that is weaker in its power. As Massachusetts has shown, voter approved laws remain subject to the check and balance of subsequent legislative action, which in turn is checked by traditional balance of powers built into state and federal constitutions. The ballot initiative process has a demonstrable capacity to force legislative action, a democratic strength in its own right.

Connor Mullen anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Connor Mullen anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

What are the Merits of a Merit-Based Immigration System?

In early November 2017, a man drove a truck onto a bike path in New York, killing eight and injuring thirteen. The suspect was a lawful permanent resident who received his immigrant visa through the diversity lottery program. This program allocates fifty thousand immigrant visas for foreign nationals from “countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States.” Just a month later, in early December 2017, another man attempted a terrorist attack in New York using a homemade pipe bomb, injuring five. This suspect also was a lawful permanent resident, but he received his immigrant visa through the family-based immigrant visa category that allows siblings of U.S. citizens to immigrate to the U.S. based on that relationship.

Although immigration has arguably never left the spotlight in recent years, these two events brought it to the forefront once again. More specifically, President Trump used both instances immediately as an example of why our immigration system needs an overhaul. The viewpoint of the President and many others is that these events indicate immigration must be reformed to permit fewer routes to lawfully immigration into the United States. President Trump’s plan is to limit family-based immigration to only spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens (it now includes extended family like siblings or parents of U.S. citizens) and to introduce a points-based immigration system to “protect U.S. workers and taxpayers.” To do so, he has thrown his support behind the RAISE Act (House bill 3775 and Senate bill 1720) two substantially similar bills that seek to “establish a skills-based immigration points system, to focus family-sponsored immigration on spouses and minor children, to eliminate the Diversity Visa Program, [and] to set a limit on the number of refugees admitted annually to the United States.” Neither version of the bill has left committee. Currently, foreign nationals can immigrate to the U.S. through the diversity lottery program, through family sponsorship, through employment sponsorship, or as a refuges or asylum seeker.

The proposed skills-based program is not the first of its kind. Canada was the first country to introduce a points-based system, with Australia and the United Kingdom following. Generally, these programs allocate points for certain attributes, such as age, education, and English-speaking ability. The United States program would allocate points based on age, level of higher education, English ability, job offer, and “extraordinary achievements.” Higher points are granted for applicants who are in their late 20s (i.e. of prime working age), who have earned a graduate or professional degree, who speak English fluently, and who have a high salaried position offered to them. Extraordinary achievements, like Nobel prizes or Olympic medals, offer additional points. Furthermore, points can be allocated for significant investment in the U.S., a revised version of the “EB-5” employment based category, which currently applies to foreign nationals that have invested $1 million in the U.S. Under the RAISE system, about 2% of Americans would qualify for an immigrant visa.

Professors Ayelet Shachar and Ran Hirschl argue that “[p]icking winners, in this context, comes very close to resembling headhunting practices, turning immigration officials and other policymakers, as well as public and private actors with devolved authority, into enterprising recruiters of super talent.” (at 87) These merit-based programs ultimately “prioritize brains, talent, and special skills.” (at 100) Immigration attorneys Chris Gafner and Stephen Yale-Loehr argue that “the point lottery should be a meritocracy based upon each applicant’s ability to contribute to the national interest. (at 210, emphasis added) They argue it would provide a more objective basis for adjudication of immigrant visa applications, “ensur[ing] that qualifying immigrants have the tangible qualities and knowledge that will truly enhance U.S. interests.” (at 208) The argument for merit-based immigration is that it supports national interests by attracting foreign nationals that are more likely to contribute to the U.S.

Professors Ayelet Shachar and Ran Hirschl argue that “[p]icking winners, in this context, comes very close to resembling headhunting practices, turning immigration officials and other policymakers, as well as public and private actors with devolved authority, into enterprising recruiters of super talent.” (at 87) These merit-based programs ultimately “prioritize brains, talent, and special skills.” (at 100) Immigration attorneys Chris Gafner and Stephen Yale-Loehr argue that “the point lottery should be a meritocracy based upon each applicant’s ability to contribute to the national interest. (at 210, emphasis added) They argue it would provide a more objective basis for adjudication of immigrant visa applications, “ensur[ing] that qualifying immigrants have the tangible qualities and knowledge that will truly enhance U.S. interests.” (at 208) The argument for merit-based immigration is that it supports national interests by attracting foreign nationals that are more likely to contribute to the U.S.

However, the points-based system is not without its criticisms. First, there are human rights concerns. Specifically, this system restricts freedom of movement and discriminates against large classes of foreign nationals, both of which are designated as human rights under international law. (at 286) Second, this restricts the movement of human capital by limiting the number of foreign nationals who can lawfully immigrate (or even enter) the U.S., which is not necessarily a sound economic policy. (at 289) Finally, it is not entirely clear that these systems have been effective in those countries in which it has been implemented. For instance, the Canadian program has become notorious for extremely long waiting times and for underutilizing the highly skilled foreign nationals it attracted. In the UK, businesses have asked for special treatment or exceptions because of the need for foreign workers that would not otherwise qualify under the point system. Thus, despite its lofty goals, the RAISE Act is not without flaws.

This bill lacks support in Congress. Additionally, Trump has been criticized for the timing of his support for RAISE: “Trump's immediate labeling of the attack as a terrorist act and his calls for policy actions contrasted with his responses to the violence and a killing by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va., in August — Trump wouldn't blame the neo-Nazis solely and said then he doesn't rush to discuss incidents without the facts — and to the mass killings in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, after which he said it was too soon to discuss gun laws.”

Furthermore, this is not the only route to immigration reform. In the House, the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act offers an expanded immigration system. This bill eliminates per-country numerical limitations for employment-based visas. To immigrate through employment sponsorship, the current system allocates a limited number of visas based on the foreign nationals’ country, with a significant backlog for foreign nationals from certain countries, namely India, China, and the Philippines. This could leave foreign nationals waiting to up to ten years to complete the immigration process. For example, certain Indian nationals who began the immigration process in 2006 are still waiting for visas to be available. By eliminating the per-country numerical limitations, those Indian nationals would finally be able to receive lawful permanent resident status in the United States. This bill also increases the numerical limitations set for family-based immigrant visas. Like RAISE, this bill is still stuck in committee.

Neither bill seems to be garnering much attention, even with the President’s support for RAISE. There is an irony in the nation of immigrants trying to significantly restrict immigration. Of course, the issue is not as simple as turning away immigrants. However, at its core, that seems to be what RAISE is doing. The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act may not solve the problem either. It could be more of a temporary fix than a permanent solution or it could introduce different issues. Overall, neither bill seems to satisfy the need for immigration reform. They both propose reform while lacking a resolution to the controversial issue that prevails in the public eye.

Nancy Williams anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Nancy Williams anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Whose Legislation is it, Anyway?

It seems that after every mass shooting, the gun control debate transforms into a discussion about mental illness. Was the shooter mentally ill? If so, some gun rights advocates will deflect from the issue of gun safety and argue for mental health reform while gun control activists will argue for stricter gun laws–specifically those that make it harder for people with mental illnesses to buy guns. The most recent Las Vegas and Parkland shootings are no different. Despite the copious research suggesting that the existence of a mental illness correlates much more strongly with suicide than it does with interpersonal crimes, mental illness is once again being deemed the culprit. Of note is Speaker Ryan’s call for mental health reform, which he described as a “critical ingredient” in preventing further mass shootings. Ryan was subsequently questioned as to whether he thought repealing the Social Security Rule (a rule that expanded background checks to include Social Security data on people with mental illnesses) was a mistake. When pressed on the issue, Ryan argued that the Obama administration rule was an infringement on Second Amendment rights. President Trump has also advocated more treatment for people with mental illnesses as a solution to gun violence.

Although some federal laws designed to prohibit gun access to citizens with mental illnesses exists, it is limited and under-enforced. Following the shooting at Virginia Tech, President Bush signed the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 into law, which attempted to identify individuals who are unqualified to possess guns due to mental illnesses or criminal backgrounds. This law proved to be inadequate; most notably when a mentally ill man, Adam Lanza, killed 20 first grade students and six teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. In response, President Obama proposed the Social Security Rule, which added more mental health records to the national background check system but was removed by Republicans in Congress under the Congressional Review Act in February of 2016.

limited and under-enforced. Following the shooting at Virginia Tech, President Bush signed the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 into law, which attempted to identify individuals who are unqualified to possess guns due to mental illnesses or criminal backgrounds. This law proved to be inadequate; most notably when a mentally ill man, Adam Lanza, killed 20 first grade students and six teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. In response, President Obama proposed the Social Security Rule, which added more mental health records to the national background check system but was removed by Republicans in Congress under the Congressional Review Act in February of 2016.

There is a wide political divide in the gun control arena, with 79% of Democrats agreeing with the statement “it is more important to control gun ownership than protect gun rights,” compared to only 9% of Republicans. In fact, this divide has widened substantially since 2012, when 62% of Democrats and 21% of Republicans agreed with the statement.

However, despite this deep division, the issue of gun restrictions for those with mental illness stands as a unique common ground. According to a Pew Research poll from June 2017, 89% of both Republicans and Democrats support restrictions that would prevent people diagnosed with a mental illness from purchasing guns. No other gun policy proposal was found to have the same kind of bipartisan support, though barring gun purchases by people on no-fly lists and background checks for private sales and at gun shows come close.

Even more striking is the support for preventing people with mental illnesses from obtaining guns among gun and non-gun owners. Again, there is wide agreement amongst the two groups: 89% of both gun owners and non-gun owners support this policy proposal. Again, there is no other policy proposal that garners the exact same support amongst gun-owners and non-gun owners. Moreover, 82% of those who say it is more important to protect gun rights rather than control gun ownership actually favor laws that prevent the mentally ill from buying guns, compared with 77% support amongst those who say it is more important to control gun ownership.

Given that the policy restricting access to guns for those with mental illnesses is so widely accepted amongst Democrats and Republicans, gun owners and non-gun owners alike, why don’t we have a more robust policy in place?

One hypothesis is the National Rifle Association’s opposition to this type of gun control proposals and their generous campaign contributions to Republican politicians. In the 2016 election cycle, the NRA gave over $77,000 to the Republican National Committee, and $838,215 to individual federal congressional candidates. In addition, the group spent over $30 million in support of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, more than any other outside group, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Opensecrets.com, a campaign finance accountability website, wrote that “[t]his election cycle, the NRA spent more than $52 million—a number that will rise as final campaign finance figures are tallied — to carry on its effort to increase Republican control of government.” In a news article following“The NRA, of course, was among the earliest and staunchest supporters of Trump’s presidential bid. We thank him for his quick action on this measure and look forward to working with him and the pro-gun majorities in Congress to protect Americans’ Second Amendment rights.” Trump responded at the NRA convention in April where he stated “You came through big for me, and I am going to come through for you.”

As it turns out, even NRA members support legislation that prevents those with mental illnesses from purchasing guns. A July 2017 Pew Research poll that controlled for partisanship found that 79% of Republican members of the NRA support this policy proposal. However, NRA members also report a general level of satisfaction with the organization’s political authority. Only 9% of NRA members say that the organization has too much influence over gun laws and about six in ten members say that they are satisfied with the amount of influence that the organization has over gun laws.

Thus, it seems the future for the gun debate may be determined not by the popularity of the ideas proposed, but by the strength of Americans’ allegiance to a very powerful group in Washington. Either that, or these ironies tainting the gun debate remain a mystery.

Jessica Goldman anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Jessica Goldman anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May, 2019.

Footloose in New York City–The Repeal of the Cabaret Act

The 1984 film, Footloose, imagines the small, midwestern town of Bomont, where dancing and rock’n roll music have been banned, only to be redeemed in the end by a teenager’s impassioned plea. Footloose’s plot may seem farfetched but a law with similar intent has gripped New York City since 1926 when the city passed the Cabaret Act. Under the Cabaret Act, any place open to the public that sells food or drinks, alcoholic or not, including “pubs, taverns, and discos,” are required to obtain a license if they want to allow dancing in the establishment. One of the pre-requisites for a cabaret license states that “cabarets” must have video surveillance and security on the premises at all times. However, after 90 years of forcing most of its bars and nightclubs to effectively operate like the clandestine prom from the end of Footloose, New York City Council member Rafael Espinal and Mayor Bill de Blasio have finally brought dancing back to New York City.

The cost of obtaining a cabaret license was inexpensive, ranging from $150 to $1,250 (with minor additional costs), but the process required to get a license and to meet the accompanying surveillance requirements were particularly onerous. To obtain a cabaret license, an establishment had to submit extensive and intrusive records about both the business and building where the establishment is located, as well as receive approvals from the Fire Department, a licensed electrician, and the local Community Board. Due to these overwhelming requirements, and a lack of consistent enforcement, there were only 104 licensed “cabarets” in the entirety of New York City as of 2017. Most establishments where dancing occurs are unlicensed and can potentially be subject to severe penalties.

The cost of obtaining a cabaret license was inexpensive, ranging from $150 to $1,250 (with minor additional costs), but the process required to get a license and to meet the accompanying surveillance requirements were particularly onerous. To obtain a cabaret license, an establishment had to submit extensive and intrusive records about both the business and building where the establishment is located, as well as receive approvals from the Fire Department, a licensed electrician, and the local Community Board. Due to these overwhelming requirements, and a lack of consistent enforcement, there were only 104 licensed “cabarets” in the entirety of New York City as of 2017. Most establishments where dancing occurs are unlicensed and can potentially be subject to severe penalties.

The Cabaret Act, as originally passed, was a blatantly racist law, targeting African American jazz clubs in Harlem. When passing the law, the Board of Alderman used coded racist language in their rationale, referring to the individuals going to the dance halls as “wild people.” At the same time, the Aldermen exempted large hotels in upper class, primarily Caucasian areas, from the licensing requirement. Until 1967, the law also required musicians who played in establishments with liquor licenses to obtain “cabaret licences” as an individual. As the process of obtaining a musician license required a criminal background check and could be revoked for almost any reason, many prominent jazz musicians were unable to perform in New York City clubs, including Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Thelonious Monk.

check and could be revoked for almost any reason, many prominent jazz musicians were unable to perform in New York City clubs, including Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and Thelonious Monk.

While New York City officials have occasionally made concerted attempts to crack down on unlicensed “cabarets,” wider scale closure movements occurred in the aftermath of nightclub fires in 1976, 1988, and 1990. For long periods of the Cabaret Act’s history, there was almost no enforcement at all, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s. However, beginning with Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s election in 1994, New York City began to strictly enforce the cabaret law as part of Mayor Guiliani’s quality-of-life initiatives. Through his Multi-Agency Response to Community Hotspots, or MARCH, Mayor Guiliani directed several municipal agencies to scrutinize establishments for violations, with the purpose of curtailing the city’s nightlife. Some people believe that Mayor Guiliani’s strict enforcement of the cabaret law contained a racial element similar to the law’s original intent.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration continued Mayor Guiliani’s crackdown on New York City’s nightlife, employing the cabaret law as well as noise ordinances and a ban on smoking in public places, to severely limit the proliferation of nightclubs. Towards the end of his tenure in office, Mayor Bloomberg considered repealing the cabaret law but ultimately failed to do so. Following his election, Mayor de Blasio relaxed enforcement of the cabaret law and, and after over 90 years, repeal finally became a reality.

In 2017, City Council member Rafael Espinal introduced several bills to reform New York City’s nightlife, including repealing the Cabaret Act. On September 19, 2017, Mayor de Blasio signed bill number 1688-2017 - which amends the New York City charter, in relation to establishing an office of nightlife and a nightlife advisory board - into law. The law establishes a Nightlife Advisory Board and an Office of Nightlife to examine the issues affecting the city’s nightlife and to make recommendations to the Mayor for improvements. The bill passed almost unanimously, with only City Council member, Rosie Mendez, voting in the negative.

The Cabaret repeal, bill number 1652-2017 subchapter 13, however, retains similar security and surveillance requirements to those under the Cabaret Act, including having video surveillance cameras and security guards in all nightlife establishments with dancing. The bill defines a nightlife establishment as one that is “(i) open to the public after 12:00 a.m. at least one day each week; (ii) is required to have a license to sell liquor at retail pursuant to the alcohol beverage control law; and (iii) satisfies at least two of the following factors: 1. At least 2500 square feet of such establishment is open to the public; 2. Has an occupancy load of at least 150 persons as described on the certificate of occupancy; or 3. Imposes a fee for admission at least once a week.”

On November 27, 2017, Mayor de Blasio signed Int. 1652-2017, officially repealing the Cabaret Act. de Blasio stated, “This law just didn’t make sense. Nightlife is part of the New York melting pot that brings people together. We want to be a city where people can work hard, and enjoy their city’s nightlife without arcane bans on dancing.”

In March 2018, Mayor de Blasio appointed the City's first "Night Mayor," Ariel Palitz. Mayor Palitz will be paid $130,000-a-year to lead the newly created Office of Nightlife that has a $300,000 annual budget. Palitz is the former owner of now-closed East Village nightclub Sutra, which was once labeled the city’s loudest watering hole.

It appears that New York City is finally free of its connection to the fictional town of Bomont.

Peter Lubershane anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Peter Lubershane anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Pharmacies Try Their Hand at Opioid Policy

The opioid crisis has continued to grab national attention, as total drug overdoses hit yet another historic high in 2016. One of the nation’s largest pharmacies, CVS, recently joined the debate by announcing a new national opioid policy.

In February 2018, CVS started capping new opioid prescriptions at a seven-day supply. Additionally, CVS is limiting daily doses to 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) and requires medical providers to prescribe immediate-release opioids before attempting extended-release versions. The policy itself is unremarkable. CVS is merely adopting the CDC’s prescribing guidelines. In fact, 17 states have done the same or equivalent, including Massachusetts. And while it may appear strange for a retailer like CVS to forcibly limit its own sales, both pharmacies and pharmaceutical companies have faced a growing threat of litigation in recent years over the marketing and sale of prescription opioids.

Medical providers, chronic pain patients, and some drug policy experts have lodged a number of concerns in response to CVS’s new policy. These concerns not only identify some of the closely held interests in the opioid debate but also demonstrate the challenges of developing effective policy against a crisis that is rapidly evolving.

The Costs

Opioid policies fall into three main categories: preventive, treatment, and punitive. The CVS policy aims to prevent the development of new opioid use disorders (OUDs). In an effort to minimize unintended consequences, the policy carves out two administrative exceptions: first, doctors may request exemptions for certain patients, and second, employers and insurers can opt out of the program altogether. The CVS policy also aligns itself with CDC guidelines in exempting patients who are in “active cancer treatment, palliative care, or hospice care.”

While this may reassure cancer patients, other patients with chronic pain have expressed cause for alarm. For one, their access to opioids is already subject to an ongoing and heated debate within the medical community. Limited data on long-term opioid use for chronic pain management has bisected medical experts’ opinions on the evidence base, ethics, and ramifications of prescribing decisions. In 2016, the CDC entered the fray. While its guidelines recommend heavily individualized opioid treatment decisions, the CDC director placed his thumb on the scale by declaring that “[m]anagement of chronic pain is an art and a science. The science of opioids for chronic pain is clear — for the vast majority of patients, the known, serious, and too-often fatal risks far outweigh the unproven and transient benefits.”

Chronic pain patients disagree that the data are so clear-cut. Moreover, they allege that the national opioid narrative is eliciting a fear-based response among medical providers at a negative cost to their treatment. Chronic pain patients report that their providers increasingly treat them like “addicts,” an inappropriately stigmatizing term that in these cases also ignores critical diagnostic differences between substance dependency and a substance use disorder. The result can be forced reductions to a patient’s opioid prescription without warning (known as involuntary tapering) or in extreme cases a blanket office policy against prescribing opioids altogether. It is early days—too early for clear data in fact—but reports of patient suicides in the wake of involuntary tapering have already surfaced.

The CDC does not expressly require a physician to involuntarily taper a patient off of opioids. In fact, the CDC vests the authority for such individualized prescribing decisions in physicians. However, the DEA, which grants physicians’ prescribing licenses, admittedly muddled that message when it proposed broad cuts to opioid production: a 25% decrease in 2017 and a 20% decrease in 2018. Moreover, punitive DEA actions against physicians regarding opioid prescription conduct increased fivefold between 2011-2016. While the penalties are clear and steep (including loss of medical licensure and criminal charges), what conduct triggers those penalties is less clear. Thus, the combination of liabilities without a clear safe harbor incentivizes an overly strict interpretation of federal policies in ways that may harm patients.

The CDC does not expressly require a physician to involuntarily taper a patient off of opioids. In fact, the CDC vests the authority for such individualized prescribing decisions in physicians. However, the DEA, which grants physicians’ prescribing licenses, admittedly muddled that message when it proposed broad cuts to opioid production: a 25% decrease in 2017 and a 20% decrease in 2018. Moreover, punitive DEA actions against physicians regarding opioid prescription conduct increased fivefold between 2011-2016. While the penalties are clear and steep (including loss of medical licensure and criminal charges), what conduct triggers those penalties is less clear. Thus, the combination of liabilities without a clear safe harbor incentivizes an overly strict interpretation of federal policies in ways that may harm patients.

Beyond the legal liabilities, physicians have also voiced concerns over the increasing intrusion of third parties into treatment decisions. The CVS policy allows a doctor to request exemptions for certain patients, but does not specify its criteria for granting exemptions or if there are caps on the number of exemptions a doctor may request or receive. Some doctors worry the additional administrative requirements to apply for CVS exemptions will burden already overtaxed primary care physicians, leaving patients with delayed or insufficient care. For example, one study found that physicians already spend two hours on paperwork for every hour of treating patients. The CVS policy will increase that paperwork burden for physicians who choose to file for opioid patient exemptions.

Without further research on long-term opioid use, clear safe harbors for prescribing compliance, and a significant increase in the number of medical specialists trained in pain management, some patients and doctors share the concern that this prevention policy will come at unintentional costs to patients with chronic pain.

The Benefits

Much of policy derives from a cost-benefit analysis. If prescription opioids are the source of most new cases of OUDs, then some risk to patients with opioid dependencies (like those managing chronic pain) may arguably be worth strictly limiting their supply. Thus, the $78.5 billion question remains: are prescription opioids presently the main cause of new OUD cases?

A growing subset of drug policy experts say no. While prescription opioids undoubtedly contributed to the opioid epidemic in the past, recent data show that opioid prescriptions continuously decreased from 2010-2015. During that same time span however, opioid mortalities continuously increased. In fact, heroin increasingly represents the initiating opioid of use for new OUD cases, not oxycodone or other prescriptions. These data suggest that the over-prescription of opioids has been largely corrected and that new and stricter prescription limits moving forward may offer only marginal benefits.

The debate over CVS’s initiative mirrors many of the challenges of developing effective opioid policy at the state level. The opioid epidemic is rapidly evolving whereas drafting and passing legislation can take years to accomplish. In that same time span, the drop in prescription rates between 2010-2015 as well as the emergence of heroin as an initiating opioid have shifted the opioid epidemic, throwing into question just recently passed prescription-focused legislation. In short, the opioid crisis is both testing and demonstrating the limits of the legislative process.

Second, even if a legislature could sustain a multi-decade focus on continually revising opioid legislation, any attempt to do so effectively would require massive data gathering. Currently however, state medical examiners have already passed their breaking points, whether from running out of room, running out of money, or burnout. Yet these examiners play a crucial role in accurately identifying the cause of death for overdoses. Thus, even accurately tracking changes in cause of death alone would necessitate a massive influx of resources, in terms of additional personnel, time, and training for standardization. Beyond tracking overdoses, states would furthermore have to allocate additional resources to continuously monitor changes in initiating opioid use and to what extent supply limitations (like those currently placed on prescriptions) result in a substitute demand for more harmful illicit opioids like fentanyl.

Third and finally, the unintended effects of legislation matter just as much as the intended. A complex mesh of societal, punitive, and regulatory forces have created powerful disincentives for physicians to prescribe opioids or treat patients who need them. In particular, the stigmatization of chronic pain patients incentivizes withholding treatment for moralistic rather than medical reasons. The threat of criminal prosecution and loss of medical licensure incentivizes avoiding even relatively benign conduct for fear of triggering DEA or state investigation. Finally, the paperwork barriers formed by each new layer of regulatory compliance incentivize avoiding time-consuming patients, like those who require opioids. Thus, the exemptions that CVS and other state policies designed to safeguard individualized treatment decisions are likely insufficient to counterbalance the opposing disincentives. Effective policymaking requires a careful calculation of both direct and indirect incentives, far beyond the scope of a single prescription policy.

Going forward, CVS (and the states) should consider policy alternatives that expand provider choices rather than restrict them. For example, CVS could begin offering the abuse deterrent formulations (ADFs) of opioids. The FDA recommends ADFs as they offer the same pharmacological benefits as regular opioids but exist in a form that is harder to physically alter for off-label use. Currently, CVS does not cover any of the ten ADFs approved by the FDA. By offering a new prescriptive tool instead of restricting an existing one, this alternative might maintain some of the same intended preventive benefits without triggering an incentive to drop chronic pain patients.

Moreover, the addition of ADF coverage would allow for greater flexibility on a state level. Many states are in the process of or have recently completed crafting comprehensive legislative packages (including combinations of preventive, treatment, and punitive solutions). CVS’s uniform national policy may interfere with these efforts and make addressing unique state needs more challenging than necessary.

In summary, the benefits of CVS’s opioid policy are unlikely to outweigh its harms. The CVS policy provides no new guidance as it merely mimics the existing CDC policy, but it does add new layers of time-consuming compliance for providers pursuing medically-valid exemptions. Pharmacies and other retailers would do better to provide additional support to the existing state and federal opioid infrastructure than begin imposing new requirements upon it.

Caitlin Scott anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2019 and plans to practice Health Law.

Caitlin Scott anticipates graduating Boston University School of Law in May 2019 and plans to practice Health Law.

“Am I Free to Go?” – It Depends On Who You Ask

Typically, when criminal proceedings against a person in state or local custody have been settled, he or she is free to go. This can occur either after that the individual's charges have been dismissed, they have posted bail, or their jail sentence has been completed. Yet, for years there has been confusion among states whether exceptions to this process can be made for certain immigrants. The confusion focuses on whether or not state or local law enforcement officials have the authority to detain an immigrant based solely on a request, or detainer, from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In other words, is an immigrant free to go once the criminal proceedings have been settled, or do these ICE detainer requests carry some legal weight? The answer to that question changes depending on who you ask.

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts was recently confronted with this question and on July 24, 2017 it issued a ruling in Commonwealth v. Lunn limiting the ability for state and local law enforcement officials to assist with federal immigration enforcement. To help address the issue, the court proceeded to “look to the long-standing common law of the Commonwealth and to the statutes enacted by our Legislature.” Ultimately, the court concluded that “nothing in the statutes or common law of Massachusetts authorizes court officers to make a civil arrest in these circumstances.” It was this language that presumably opened the door to recent legislation that was filed by Governor Baker August 1, 2017.

According to Governor Baker, this bill “fills the statutory gap identified by the SJC” and “authorizes, but does not require, state and local law enforcement to honor detention requests from Immigration and Customs Enforcement for aliens who pose a threat to public safety.” It attempts to accomplishes this mission, and avoid running up against the holding in Lunn, by narrowing the scope of the legislation. The bill is supposed to establish minimum criteria for an immigrant to be deemed a public safety threat by focusing “on those who have been convicted of serious crimes such as murder, rape, domestic violence and narcotics or human trafficking.” Furthermore, any detention in excess of 12 hours that results from compliance with a detainer request or an administrative warrant would be subject to judicial review. On its face, this bill seems to pass muster with the holding in Lunn and attempts to strike a healthy balance between public safety and immigrant rights, but there are some serious legal and moral issues that this bill either misguidedly collides with or willfully ignores.

First and foremost, the bill does not target only people convicted for atrocious crimes, despite claims to that effect. Under the bills current language, an immigrant can be detained by state or local officials for immigration purposes, if he or she “has engaged in or is suspected of terrorism or espionage, or otherwise poses a danger to national security [emphasis added].” These standards clearly fall short of a conviction. It also allows for detention in cases where “the person has been convicted of an offense of which an element was active participation in a criminal street gang, as defined in 18 U.S.C. § 521(a).” Unfortunately, the methods that many state and local police officials use to identify gang membership, have come under much scrutiny because of their unreliability, lack of transparency, and minimal oversight. In Boston, something as simple as the color of an immigrant’s attire, or as ironic as being the victim of an attack by another gang, can lead police to label an immigrant a gang member. Furthermore, the bill states that a person who has been convicted of an aggravated felony, as defined under 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(43), can also be detained. Again, the use of said language can be very misleading and troubling. For the purposes of federal immigration law, Congress has broad latitude to label crimes as aggravated felonies and an offense need not be “aggravated” or a “felony” to be considered an aggravated felony (see 8 USC § 1101(a)(43)). As the ACLU of Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition recently stated in a joint memo, “the premise that any legislation authorizing warrantless detention of immigrants is necessary for public safety is misguided.” Our current laws already provide communities with the necessary tools to take custody of people who pose a danger to public safety and local officials already have procedures for notifying ICE about current detainees.

Equally important to the determination of whether this is a well-crafted and well thought out piece of legislation, is the constitutional analysis of the bill. Importantly, a footnote in the Lunn decision noted that the court “do[es] not address whether such an arrest, if authorized, would be permissible under the United States Constitution or the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights.” And although the court chose “to defer to the Legislature to establish and carefully define” the authority for court officers to arrest for federal civil immigration offenses, it emphasized in an additional footnote that it expressed “no view on the constitutionality of any such statute.” Governor Baker’s bill tries to take advantage of this unanswered question, but unfortunately it would invite costly and unnecessary litigation about its constitutionality if it passes; litigation that would almost certainly hold ICE detainers as unlawful. First, Article 14 of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights prohibits warrantless arrests for civil infractions. Second, in the case Morales v. Chadbourne the First Circuit court of appeals ruled that detaining a person based solely on an ICE detainer request is a violation of their Fourth Amendment right. The court explained that "[t]o hold otherwise would mean that the approximately 17 million foreign-born United States citizens could automatically be subject to detention and deprivation of their liberty rights."

Although everyone wants to live in a safe community, this bill promotes the false narrative that immigrants are associated with criminality, while further entangling state and local law enforcement in federal immigration enforcement. In the long run, bills such as this one can be dangerous to the administration of justice and to public safety. Although most people would agree that our federal immigration system is broken, states should be careful to protect the civil rights of all its residents.

Mario Paredes anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2018.

Kentucky Medical Review Panels: A Toe in the Water of Tort Reform

In March, the 2017 Kentucky General Assembly passed SB4: AN ACT relating to medical review panels. Sponsored by Senator Ralph Alvarado, a physician from Winchester, the bill establishes medical review panels as a first stop for any medical malpractice claim in Kentucky. The new statute provides that, prior to filing a lawsuit for medical malpractice against a health care provider or institution, all claims shall be reviewed by a medical review panel. This post will explore the new law and describe the difficulty of predicting the exact effect that the medical review panel will have on malpractice suits in Kentucky.

To file a medical malpractice suit in a Kentucky court, a complainant must present their potential claim to the panel and have received an opinion regarding their claim. The panel, made up of three healthcare providers and a non-voting attorney chairman, has up to nine months to give its opinion of the malpractice-related claim. The panel can decide that a plaintiff’s case has no merit, that there was a failure by the defendant to provide proper care, or that there was a failure to provide proper care, but the misconduct did not lead to a negative medical result. Regardless of the opinion issued by the panel, the plaintiff may still take their case to court. The opinion issued by the panel is admissible at trial and the doctors on the panel may be called as witnesses.

Why put these hurdles to litigation in place? Critics have long argued that too many meritless medical malpractice claims are filed each year, which causes health care provider liability insurance to skyrocket and encourages the practice of “defensive” medicine. Concerns that too many malpractice claims are “frivolous and request unrealistic damages” date back to the mid-1970’s. Another concern which prompted this change in the law, according to Rep. Robert Benvenuti of Lexington, is that the current medical malpractice process is slow and “drags on for years and years and years [and] it ends by the judge encouraging or sometimes ordering mediation.” According to Benvenuti, the panels speed up the process by putting mediation on the front end.

Kentucky is only the latest in a number of states which have implemented these medical review panels. Medical review panels have been the proposed and implemented solution for the highly litigious area of medical malpractice, but it begs the question, do they actually work? The data varies by state, and the extent of tort reform implemented in different states can make it difficult to determine the effect of just implementing medical review panels. For example, data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners found that malpractice premiums in California grew much more slowly than the rest of the nation after it passed comprehensive tort reform. Unlike Kentucky, California’s tort reform included caps on non-economic damages, changing payout requirements, limitations on attorney fees, and a required 90-day notice to file a lawsuit, but does not require medical review panels.

Studies on the isolated effect of just medical review panels are sparse. The most comprehensive study on the effect of medical review panels dates all the way back to 1986, finding that the panels caused an overall increase in the number of disputes, overall costs, and lengthening of time of the process. However, a more recent study commissioned by the American Medical Association (an advocate of tort reform) in 2008 found that states with screening panels generally medical liability insurance rates 20% below the national average and had a higher percentage of cases that settled more quickly or closed without a payout. Maine, whose panel law has been in place for more than 30 years, had 20-30% lower insurance rates than neighboring New Hampshire prior to New Hampshire’s passing of its own panel law. Between 1996 and 2006, the Senior Vice President of Medical Mutual Insurance in Maine stated in 2009 that average expenses for medical malpractice claims in Maine were 66% lower than in New Hampshire, and only 2.5% of claims went to trial, as compared to 7% in New Hampshire.

Studies on the isolated effect of just medical review panels are sparse. The most comprehensive study on the effect of medical review panels dates all the way back to 1986, finding that the panels caused an overall increase in the number of disputes, overall costs, and lengthening of time of the process. However, a more recent study commissioned by the American Medical Association (an advocate of tort reform) in 2008 found that states with screening panels generally medical liability insurance rates 20% below the national average and had a higher percentage of cases that settled more quickly or closed without a payout. Maine, whose panel law has been in place for more than 30 years, had 20-30% lower insurance rates than neighboring New Hampshire prior to New Hampshire’s passing of its own panel law. Between 1996 and 2006, the Senior Vice President of Medical Mutual Insurance in Maine stated in 2009 that average expenses for medical malpractice claims in Maine were 66% lower than in New Hampshire, and only 2.5% of claims went to trial, as compared to 7% in New Hampshire.

Other states, like Nevada, have found mixed success, causing thirty states to repeal panel laws and often replace them with other methods of tort reform. Nevada found out the hard way that if doctors on the panel and insurance companies fail to play by the rules, the functionality of medical panels becomes moot. Sen. Alvarado has stated himself that the doctors of Kentucky must be ready to serve on the panels if called upon. Additionally, the Kentucky Medical Association Director of Advocacy and Legal Affairs stated that the panels will “succeed or fail based largely on the participation of physicians,” and that success of the panels will guide future tort reform in Kentucky.

Another claim by the proponents of the new law are that medical review panels will bring speedier resolutions to malpractice claims. How speedy of a process this will prove to be remains to be seen. The panels have up to nine months to make a decision, and any other claims dependent on the medical malpractice claim are stayed from the time the complaint is filed with the panel until the decision is made. However, potential plaintiffs who receive negative opinions from the panel may be discouraged from pursuing their claim in court or choose to settle more quickly.

Regarding Rep. Benvenuti’s comparison of the panel process to mediation, this association is flawed, since the opinions are admissible and the panel members may be called as witnesses at trial. Where required mediation would encourage an honest look at the merits and encourage settlement of these medical malpractice claims out of court, which the proponents of this legislation claimed as one of their goals, this panel process could very well just turn into an out of court trial that proves to be just as costly for claimants. Some claimants with legitimate claims of medical malpractice may be deterred from pursuing their medical malpractice claims entirely, because the total cost and length of litigation could well be extended by lengthy statements and extensive discovery. Also unclear is how the panel system will affect billing for claimants. Often, medical malpractice plaintiffs are billed on contingency. Changing the system may make pursuit of these claims more cost prohibitive for potential plaintiffs.

Not only seen as potentially cost-prohibitive and discouraging to litigation, some view the medical review panels as a bar to litigation because it restricts the right of people to plead their cases in court. The Franklin Circuit Court struck down Kentucky’s new law in October 2017, and the case will be heard by the Kentucky Supreme Court in its upcoming session in 2018.

While the full effects of Kentucky’s new medical review panels remain to be seen, the likely next step for the Kentucky legislature will not be a surprise. If the panels are successful and accurately weed out frivolous malpractice claims, then the average payout for medical malpractice suits will likely increase. Claimants with favorable opinions from the panel will likely continue to pursue their claim and can use the panel opinion to their advantage in court to get higher payouts. The second main concern with medical malpractice litigation is that plaintiff request unrealistic damages. Likely the Kentucky General Assembly will want to temper increased payouts for medical malpractice suits. The American Medical Association considers Kentucky as a state in a medical malpractice crisis because it has no laws capping non-economic damages in medical malpractice suits. Senator Alvarado, who filed the bill creating these medical review panels, has already expressed his desire to institute a constitutional amendment which would cap damages for pain and suffering in medical malpractice claims. With a Republican super-majority in Frankfort, it seems as though Kentucky is on the verge of diving in to full tort reform.

Joye Beth Spinks anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.

Joye Beth Spinks anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2019.