Category: State Legislation

Boston T Party: Using Transatlantic Policymaking to Push Free Public Transit in Massachusetts

If you’ve lived anywhere near the Boston metropolitan area in the past few months, you will no doubt have faced a barrage of discussion in the media and manifestos about the prospects of making the T (Boston’s public transport system) free for all riders. Mayor Michelle Wu has headed up the push to make the historic MBTA free and used it as a major issue in her Mayoral campaign. Mayor Wu wrote an Op-Ed in the Boston Globe as far back as January 2019 advocating for free public transit, citing improvements to air quality, economic mobility, racial equity. Wu even donned a golden, token style pendant with the classic T logo in many of her campaign advertisements. This in-vogue concept also has the support Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley and former Democratic candidate for governor and former state senator Ben Downing vowed to “make the T free by the end of his first term.” Another former gubernatorial candidate state senator Sonia Chang-Diaz proposed a state-wide free public transportation agenda, starting with buses. There have been small steps toward this goal such as making three bus lines free for two years. This article is designed not to demonstrate the positives of free public transit, of which I am a strong proponent, but how we can make the program more palatable for those on Beacon Hill.

But there are sceptics and critics at all levels of Massachusetts politics. Former Mayoral candidate Annissa Essaibi George would criticize the idea of going entirely “fare-free” as fanciful, while House Speaker Ron Mariano and Senate President Karen Spilka have not committed to a fare-free MBTA system. Importantly, current Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker opposed the idea of eliminating fares, unless “Boston is willing to pay.” Baker does raise some compelling points, asking why those in “the Cape, on the North Shore, in Central or Western Mass” should pay for Boston riders. Currently, fares account for only around a third of the MBTA’s $2 billion budget, so how do you make up this shortfall in the utopia of a fare-free city?

This is a bold, progressive, and commendable policy proposition, and while it may be very popular amongst locals, there is not much appetite for it on Beacon Hill due to cost. Most proponents suggest funding this program by raising taxes. Ben Downing proposed using some of the $5 billion in funds from the American Rescue Plan Act, and tax revenue from a popular “millionaires’ tax,” as well as gas tax hikes of 10-15 cents (bearing in mind this was proposed pre-inflation and the Ukraine/Russia conflict) and a sales tax on Uber and Lyft rides. Sonia Chang-Diaz likewise has proposed levying a state millionaires’ tax to fund the policy. Michelle Wu took a slightly different approach, suggesting that “regional ballot initiatives” are the way to raise finances for a free MBTA. Regional ballot initiatives ask voters in localities in a small demographic if they approve of raising certain taxes i.e., sales, emissions, property tax. This is certainly one way to rebut Governor Baker’s “why should Massachusetts pay for Boston” argument.

Temporary funding like the ARPA is not sustainable and increased gas taxes is probably a non-starter in this age of sky high gas prices, although Sen. Downing was right to use the problem to pay for the solution. A millionaires’ tax may be a popular possibility, but may not be long-standing enough or raise enough to subsidize the T. Wu’s regional ballot initiative idea is more compelling and something we see elsewhere, (California, Colorado, Georgia etc.), but asking local riders to pay for something they want to make free seems counterintuitive.

There is room, however, for creative policymaking solutions to kill two (or three) birds with one stone. Owing to my transatlantic tendencies, I believe the city of Boston should implement a “Ultra-Low Emissions Zone” used by the city of London. The ULEZ is a mapped zone in the London city centre that, once entered, registers your license plate with cameras, and charges you £12.50 for vehicles not compliant with emissions standards. In the first year, the ULEZ brought in £400 million in revenue, equivalent to around $524 million USD. Of course, congestion charges are not free of controversy, and special considerations or permits must be given to taxis, Ubers, first responders and construction companies working in the city for a prolonged period. London is, however, significantly larger than Boston, and does not use the funds to subsidise the public transportation system. This can be done on a smaller scale within the city limits of Boston, perhaps inclusive of the area spanning the green line.

There is room, however, for creative policymaking solutions to kill two (or three) birds with one stone. Owing to my transatlantic tendencies, I believe the city of Boston should implement a “Ultra-Low Emissions Zone” used by the city of London. The ULEZ is a mapped zone in the London city centre that, once entered, registers your license plate with cameras, and charges you £12.50 for vehicles not compliant with emissions standards. In the first year, the ULEZ brought in £400 million in revenue, equivalent to around $524 million USD. Of course, congestion charges are not free of controversy, and special considerations or permits must be given to taxis, Ubers, first responders and construction companies working in the city for a prolonged period. London is, however, significantly larger than Boston, and does not use the funds to subsidise the public transportation system. This can be done on a smaller scale within the city limits of Boston, perhaps inclusive of the area spanning the green line.

What this ULEZ would do in Boston is not only grant the accessibility, economic mobility, job creation and ridership but also substantially reduce the emissions of vehicles which count towards 40% of the carbon footprint of Massachusetts. This way, you can tax the problem as well as make those who want to come to Boston pay for Boston public transit. Alongside this, the need for road maintenance, a major gripe of New Englanders, would be significantly reduced on the city’s busiest roads – a significant cost to the public purse.

An exponential increase in ridership post COVID-19, is what the T needs, and as shown by making the Route 28 bus free in a pilot scheme, ridership increases by at least 22%, something that would undoubtedly be higher in high traffic lines like the green line. Higher ridership alone can help with budgetary issues. Being able to have thousands more take the city subway into pandemic-recovering businesses and restaurants would be a welcome injection of footfall. This would be both a sustainable, and environmentally sustainable policy concept that could continually fund the shortfall that a free transit system would create in the budget.

As outlined by Attorney General and gubernatorial candidate Maura Healey, there is a growing consensus that Massachusetts infrastructure is crumbling, and drastic investment is an absolute requirement. Massachusetts is in a rare position where we can slash deadly emissions caused by vehicle pollution whilst simultaneously. The 15% of annual income that everyday Americans fork out for transportation, would be greatly reduced in metropolitan Boston. ‘But there is also momentum in the notion that environmental justice equals racial justice, and a huge step towards achieving transit justice would be taken by implementing the ULEZ to fund the hallmark of Massachusetts’ public transit system. That is how you make Boston a pioneer in sustainability, and an easy pill for Beacon Hill to swallow in one fell swoop.

Jack Ford McDonald Morton graduated from Boston University School of Law with an LLM in American Law in May 2022. He graduated from the University of Strathclyde in 2020 with an honors LLB degree in Scots and English Law. He was named a Saint Andrews Society of the State of New York scholar to attend BU Law.

Jack Ford McDonald Morton graduated from Boston University School of Law with an LLM in American Law in May 2022. He graduated from the University of Strathclyde in 2020 with an honors LLB degree in Scots and English Law. He was named a Saint Andrews Society of the State of New York scholar to attend BU Law.

Voter Suppression Laws in the Wake of Democratic Control of the Presidency and Senate

Georgia gained national attention in the 2020 election when the predominantly red state broke its 24-year streak of voting for Republican candidates in U.S. Presidential Elections. It went on to make history in early 2021 when the electorate flipped the U.S. Senate and elected Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to the U.S. Senate, respectively the first Black and Jewish Senators from Georgia.

A large part of this victory both in the White House and the Senate is attributed to Stacey Abrams, the Democrat gubernatorial candidate in Georgia’s 2018 election. Abrams’ gubernatorial campaign was unsuccessful, in large part because of voter suppression, but rather than wallow in defeat and fade into the background, Abrams became a loud, powerful voice—speaking against voter suppression and registering hundreds of thousands of voters in Georgia.

And now Republicans—in Georgia and across the nation—formally responded, pushing a huge new wave of voter suppression tactics in the name of “election integrity.”

S.B. 71

Among other legislation, Republicans in the Georgia Senate have proposed S.B. 71, which would change the definition of absentee voter entirely. For the past 15 years or so, Georgia has been a “no excuse needed” absentee voting state, but this bill would require people who wish to vote absentee to

- Be physically absent from their precinct during the election;

- Be able to perform any of the “official acts or duties” connected to the election;

- Be absent because of physical disability or because you’re required to give constant care to someone who is disabled;

- Be observing a religious holiday;

- Be required to remain on duty for the “protection of the health, life, or safety of the public”; or

- Be at least 65-years-old.

These extremely limited exceptions would put even more emphasis on the luxury and privilege of time. Many people cannot take an hour (or more) out of their daily schedules—balancing child care, housing matters, and work among the other minutiae of modern life—to go to the polls. The oft-used argument to that is “well, there are plenty of precincts where you can get in and out in 10 minutes.” And while that may be accurate, the problem is inherent in the argument itself: that it isn’t true of every precinct; and issues with fewer voting machines, voter purges, and, therefore, long waits tend to disproportionately affect liberal-voting communities in Republican controlled states.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

In Georgia, it seems like the Republicans are worried they are seeing the writing on the wall after the voter turnout in the 2020 Presidential and Senatorial elections. Though not an overwhelming victory in any of the elections, the Democrats mustered enough of a majority to win, and with continued growth in urban areas and a push for even more change in the future, it’s incredibly likely that Georgia will continue to vote blue in the future. The state has been trending that way for years, and the 2020 election could well portend what is in store for conservatives in Georgia.

Other Voter Suppression Legislation

Throughout the nation, state legislatures have begun putting forth bills that would restrict voting access—in fact, over four times more legislation that would restrict voting has been proposed than was proposed this time last year.

Georgia is not alone in limiting absentee voting. Nine other states have proposed bills that would either eliminate “no excuse” voting or crack down on the requirements for absentee voting where “excuse” voting is already in place. Other bills make it more difficult to obtain ballots in the first place by changing the laws concerning permanent early voter lists. Some measures go so far as to eliminate permanent early voter lists (which would force people now on those lists to take more steps to vote every year; Arizona S.B. 1678, Hawaii H.B. 1262, and New Jersey S.B. 3391) while others would reduce how long someone remains on the permanent absentee voter list (Florida S.B. 90).

Other proposals concern stricter voter ID requirements—a long contentious aspect of voter suppression. States that do not currently require photo IDs to vote are considering requiring them in the future, other states are trying to restrict what kinds of photo IDs can be used (New Hampshire H.B. 429, Mississippi H.B. 543), and some would force voters to include a photocopy of their ID with their absentee ballots (Texas S.B. 1). Requiring voter ID (and particularly certain types of ID) is problematic because there are not enough opportunities for people to obtain IDs—lunch hour spent at the DMV, anyone?—and cost barriers make obtaining an ID unfeasible for many disenfranchised populations. This also ties in with the legislative efforts to reduce voter registration opportunities, whether that be election day registration or limiting or reducing automatic voter registration.

Lastly, some state legislatures have decided that amplifying voter purge practices is the way forward. The practice is already flawed (and usually ineffective and unnecessary), but the proposed legislation would expand the scale of extant purges or adopt procedures that would likely result in improper purges. Texas legislators have sent a bill to the governor that would add new criminal penalties to voting processes, enhance partisan poll-watching, and ban measures previously enacted to increase access to voting. New Hampshire has gone so far as to propose a bill that would violate the National Voter Registration Act.

Staying on our toes

Although some legislation has been proposed to expand access to voting, the backlash and restrictions are what anyone concerned with protecting the right to vote should be worried about. The proposed restrictions on voting would remove people from voter rolls, make it harder to vote in person by heightening ID requirements, erect further barriers to obtaining IDs, severely limit who can vote absentee, and add arbitrary hurdles to voting by mail generally. The individual right to vote is integral to securing and maintaining American democracy, and efforts to build barriers that would make it nearly impossible for American citizens to vote are plainly wrong. Preventing voter fraud is important, but using rhetoric about “election integrity” to justify disenfranchising certain populations is classist, racist, and morally repugnant, and that is without touching the constitutional and legal issues surrounding the matter. Already, the Democrat-controlled U.S. Congress is taking steps to prevent the voter suppression promulgated by this wave of state legislation. What Republicans who are worried about votes in the hands of marginalized communities do not realize is that it isn’t a matter of barriers and restrictive legislation, it’s a matter of time. Georgia was one of the first dominoes to fall, but it won’t be the last, especially with the federal government ready and willing to strengthen voting rights and access.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Amelia Melas anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Decriminalize Everything? Oregon’s New Drug Laws

In November 2020, Oregon voters overwhelmingly decided to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of almost all hard drugs. Measure 110 went into effect on February 1, 2021. The legislation took a groundbreaking, albeit controversial step by reclassifying the possession of hard drugs. Offenses that were formally criminal misdemeanors, subjecting citizens to arrest, fines, and jail time, are now mere civil violations, subject only to a $100 civil citation, which can be avoided by participation in health assessments.

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

The measure makes possession of certain controlled substances a noncriminal violation so long as the possession is less than a specified amount:

- 1 gram of heroin;

- 1 gram of MDMA;

- 2 grams of methamphetamine;

- 40 units of LSD;

- 12 grams of psilocybin;

- 40 units of methadone;

- 40 pills of oxycodone; and

- 2 grams of cocaine.

The measure further reduces the charge from a felony to a misdemeanor for simple possession of substances where the amount is:

- 1-3 grams of heroin;

- 1-4 grams of MDMA;

- 2-8 grams of methamphetamine; and

- 2-8 grams of cocaine.

As noted by Oregon State Policy Capt. Timothy Fox, “possession of larger amounts of drugs, manufacturing and distribution are still crimes.”

The law was predicted to have a drastic impact on yearly convictions for possession of controlled substances. The Oregon Criminal Justice Commission estimated yearly convictions would decrease by a staggering 90.7%. The legislation comes approximately 50 years after President Richard Nixon famously declared his War on Drugs. While the drug war has been criticized as a racist, inhumane failure, Oregon’s recent legislation marks a significant, perhaps radical step towards restructuring the deeply flawed systems instituted over the past half century. This article will first explore the main arguments on either side of the debate regarding the wisdom and efficacy of Measure 110. Later, it will discuss some cautious conclusions and the broader implications of Measure 110 and how it might fit within the larger, national public debate regarding drug decriminalization.

The Promise

Proponents of Measure 110 see it as a much overdue remedial measure to a disastrous drug war that has done far more harm than good. Kassandra Frederique, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance (“DPA”), remarked on its passing, “Today, the first domino of our cruel and inhuman war on drugs has fallen, setting off what we expect to be a cascade of other efforts centering health over criminalization.” Supporters highlight the wisdom of shifting from a drug policy model that focuses on punishment, incarceration and criminalization to a more progressive model that sees drug use and addiction as a disease to be treated rather than a crime to be punished. From this perspective, substance use is better addressed by providing access to physical and mental healthcare and removing the stigmatization and obstacles that traditionally accompany drug charges such as the difficulty landing jobs and finding housing. “Criminalization keeps people in the shadows. It keeps people from seeking out help, from telling their doctors, from telling their family members that they have a problem,” says Mike Schmidt, district attorney for Oregon’s most populated county.

A key provision of Measure 110 earmarks a portion of cannabis tax revenues for improving and expanding the state’s treatment system, along with drug safety education and services. To date, Oregon has generated hundreds of millions of dollars for this purpose, distributed to at least 70 different organizations in 26 different counties, aimed primarily at helping providers expand services for people with low incomes and without insurance. This kind of investment is clearly a necessary part of shifting from a model oriented around the criminal justice system to a model oriented around healthcare. In addition, proponents of Measure 110 emphasize that decriminalization will ease racial disparities in drug arrests. For example, African American Oregonians are 2.5 times as likely to be convicted of a possession felony as whites. Without delving into the reasons behind this disparity, by reducing possession convictions overall decriminalization will reduce the negative effects on minority communities. Indeed, according to Theshia Naidoo, managing director for legal affairs at DPA, although the “information is not fully available yet . . . from the data we can see, there have been no drug possession arrests in the state since the decriminalization took effect.”

One major area of concern is implementation. Detractors question whether Oregon’s treatment system has the resources and functionality required to support such a fundamental shift away from the criminal justice system as the primary model for addressing drug use and executing drug policy. Are the resources provided by Measure 110 adequate to handle a corresponding substantial influx of people seeking treatment? Unfortunately, It is likely still too early to tell; but shifting from the criminal justice to the health care system is undoubtedly not going to happen overnight.

Relatedly, critics question whether a civil citation akin to a parking ticket will provide the adequate impetus and resources for users to seek help. Mike Marshall, co-founder and director of Oregon Recovers, worries that “the only way to get access to recovery services is by being arrested or interacting with the criminal justice system. Measure 110 took away that pathway.” Perhaps the threat of the criminal justice system provides users with the necessary motivation to seek treatment and the threat of a citation and potential fine is lacking in some critical respect. Decriminalization may ultimately limit access to treatment as fewer offenders are pushed into court-ordered programs. Decriminalization advocates counter that the criminal justice system’s pathway to treatment is flawed, biased and ineffectual, and point out that “on average a huge percentage [approximately 70 to 80 percent in Multnomah county] of those convicted of drug possession in the state were rearrested within three years.” Regardless, there is shockingly little data to determine what programs work best and no agreed upon set of metrics or benchmarks to judge program efficacy, either in Oregon or nationally.

The Verdict

Unfortunately, it’s likely too early to fairly assess whether Oregon’s remarkable drug policy transformation can be deemed a success. Part of this is because the transformation is still underway. Supporters of decriminalization point to Portugal as a reform model, which took more than two years to transition from a system centered around the criminal justice system to a healthcare model. Covid-19 is a another complication; Oregon’s detox clinics, recovery-focused nonprofits, and impatient facilities have been battered by the pandemic and related workforce shortages.

Nonetheless, Oregon’s bold efforts have seemingly inspired state level decriminalization efforts across the country as lawmakers in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont have all proposed similar decriminalization bills this year. The takeaway seems to be that decriminalization is a wise policy so long as recovery services are widely available. As Reginald Richardson, director of Oregon’s Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission, put it, “the use of criminal justice becomes a necessary proxy when you don’t have effective behavioral health services.” Overall, this kind of major shift in policy is daunting and will always involve overcoming unforeseen challenges, although hopefully not always to the extent of a global pandemic. Still, the Nixon-era drug policies has largely been an abject failure, and states like Oregon ought to be commended for trying, however imperfectly, to improve their approach.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Alexander Gatter anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Emergency Opportunity: Legislating Away Roe v. Wade During the Coronavirus Pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted American life, challenging mental health, physical health and the economic infrastructure of the country. Though a pandemic inherently creates adversity, one struggle that we may not have anticipated to escalate so dramatically during this time is the fight for reproductive rights. Just before the pandemic, conservative legislators and pro-life groups took sweeping action under a president who supported such restrictions, and a newly conservative Supreme Court. Now, not only is the Court hearing cases that previously would have been quickly denied under Planned Parenthood v. Casey precedent, but also new legislation and tactical moves are rapidly escalating the rollback of reproductive rights. The pro-life movement has gained momentum during the pandemic, and the question remains whether the future will reverse, or further cement conservative views on abortion.

At the outset of the pandemic, many states banned “nonessential” medical procedures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and preserve PPE. However, several states took the opportunity to classify abortion as a “nonessential” procedure, making the surgery inaccessible. At the same time, the FDA deregulated the requirements for in-person prescription of many drugs, even opioids, but continued to heavily regulate medication related to abortion.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

Medication abortion consists of mifepristone and misoprostol, two drugs taken separately to induce an abortion. Prior to the pandemic, medication abortion was already distinguished from other types of medication. Mifepristone is the only drug, out of over 20,000 FDA-approved drugs, that requires in-person dispensation, but can be ingested at home without any medical personnel present. The persistence of FDA restrictions on medication abortion combined with the prohibition on abortion as a “nonessential procedure” in some states left many women with few options. In January of 2021, the Supreme Court deferred to the FDA’s decision and allowed the restrictions to remain in place.

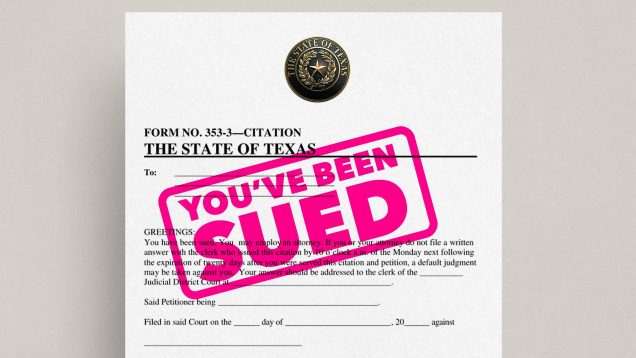

While the FDA was in legal battles over the requirements for medication abortion, conservative states began launching and defending legislation that restricted the right to a surgical abortion. During the 2021 session the Texas Legislature enacted the Texas Heartbeat Act, which bans abortion at the first sign of fetal heartbeat, which can be as early as 6 weeks. As BU Law and School of Public Health Professor Nicole Huberfeld pointed out, many women do not know they are pregnant within 6 weeks, and a “heartbeat” may mean no more than detecting an electrical pulse.

The key feature that has made Act a standout among anti-abortion bills is the citizen suit provision. The Act allows,

“any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local government entity in [the] state, may bring a civil action against any person who…performs or induces an abortion” or “aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion.”

Enforcement is exclusively through private civil actions, a self-protecting mechanism that has been thought provoking for both the courts and the public. The lack of government enforcement leads many people to believe that there was no one to sue in order to challenge the legislation through judicial review. While the legislators may have thought this workaround clever, the Court recently held in Whole Women's Health v. Jackson that abortion providers may challenge the law by suing licensing officials. Still, the limited opportunity for judicial review may leave future constitutional rights vulnerable to this same evasive structure employed by the Texas legislation.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Another nefarious aspect of the Heartbeat Act is that it allows a potentially expansive class of people to be sued, and incentivizes suits by promising a reward of no less than $10,000, should the case succeed. Further, “aid or abet” is so vague, there appears to be no limit as to who fits this category. An attending nurse could clearly get sued, but potentially so may be someone lending a car or providing therapy to someone who had an abortion. Because anyone could inform on them, and has strong financial incentive to do so, the support networks may be almost as limited as the options for obtaining an abortion in Texas.

Just before announcing its limited decision allowing judicial review of the Heartbeat Act, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs centered around pre-pandemic Mississippi anti-abortion legislation, known as the “Gestational Age Act.” This Act directly confronts the holding of Planned Parenthood v. Casey by banning abortion after 15 weeks. It lacks the workaround that Texas employed but may nevertheless garner enough support from the Supreme Court to overturn the precedent from the Roe v. Wade line of cases. While Justice Roberts seemed inclined to uphold Roe but push back the line of imposing an undue burden to 15 weeks, other justices see the challenge as a call for an all-or nothing reversal of Roe. Overturning Roe would mean a complete change in the law surrounding abortion not just because of overturning common law precedent, but also because many states have drafted trigger laws, that specify that if Roe is overturned, abortion is automatically illegal in the state.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

While the pandemic has allowed for an onslaught of attacks against the right to an abortion, surgical abortion is not the only option. Fewer women are getting abortions today than ever before, in part because contraception is more accessible. Additionally, the FDA has reversed its previous stance and permanently removed the in-person requirements for abortion medication. Many states have already written state-specific legislation that prohibits what the FDA is allowing, but the mail is not easily policed. Should the court uphold Texas Heartbeat Act and the Gestational Age Act on judicial review, medication abortion may become the new focus of legislation on both sides of the debate. Until then, the nation is holding its breath to see if these Acts can take down one of the most highly contested common law precedents—Roe v. Wade.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Julia Novick anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Time To Bring Back Happy Hour To Massachusetts?

This session the Massachusetts Legislature considered “An Act restoring happy hour to the commonwealth" SB.169 at the request of a group of Boston College Law School students. The bill would allow restaurants and bars to discount alcoholic beverages during specified times if drink prices are not changed during the happy hour; the happy hour does not take place after 10 pm; and notice of the happy hour is posted on the premises or website at least three days in advance.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

The 38-year effort against drunk driving has had a significant effect: by 2019 there were 10,142 drunk driving fatalities representing 28% of total traffic deaths. Today, AAA ranks Massachusetts first among all states for having the least severe drunk driving problem. However, it is unclear that happy hour restrictions contributed to this downward trend. For example, in 2015 Illinois legalized happy hours after a 26 year ban. According to Department of Transportation data, during 2014, the last year that happy hour was outlawed in Illinois, there were 353 alcohol-related traffic deaths—38% of all traffic fatalities. In 2019 there were 368 alcohol-related traffic deaths—36% of traffic fatalities. It appears doing away with the happy hour ban had little to no effect on alcohol impaired traffic deaths in the state. Other drunk driving measures such as the 21 year-old minimum drinking age, strict enforcement of drunk driving laws, and changing youth attitudes and behaviors surrounding drunk driving have played the largest role in the reduction in traffic deaths nationally. Still, a 2014 study found that college students greatly increased alcohol consumption during promotions and happy hours that decreased overall prices.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

The bill's findings and purposes section lists both the law’s ineffectiveness and economic factors for lifting the ban. The bill claims restoring happy hour “will support local businesses, shift patronage of bars and restaurants toward low-density hours, and benefit the public morale.”

Indeed, offering happy hour specials could help restaurants and bars boost sales during off-peak hours. In the time of Covid-19, these discounts and specials could mitigate the losses suffered during the pandemic. Joshua Lewin, a co-owner of a restaurant in Somerville and Boston argued that in the time of Covid happy hours bring in patrons during slow times of the day. Happy hours spread out the times in which people go to the restaurants as allow social distancing measures.

The proposal is also popular; a recent MassINC poll found 70% of people approved lifting the happy hour ban with only 9% strongly opposed. In addition, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (“MADD”), one of the strongest proponents for prohibiting happy hours, does not currently have an official stance on lifting the ban due to the advent of ride shares as a safeguards against drunk driving.

Allowing happy hours, however, faces significant opposition. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker is skeptical about the bill stating, “That law did not come about by accident. It came about because there was a sustained series of tragedies that involved both young and older people, in some terrible highway incidents, all of which track back to people who’d been over-served as a result of happy hours in a variety of places... I’d be hard-pressed to support changing it.”

While drunk driving and binge drinking are still a concern, drunk driving incidents have been on the decline over the last twenty years. Evidence suggests the Massachusetts prohibition of happy hour is outdated and ineffective for decreasing drunk driving. The Commonwealth should refocus its efforts to curb drunk driving through increased education and outreach programs along with tighter enforcement across the Commonwealth. Further, the Legislature should support legislation that will aid local business in any way that is practical; happy hours would give bars and restaurants a boost while helping to manage the flow of customers.

At any rate, the bill seems to be done for the session. The committee on Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure held a hearing on August 30, 2021, and in January 2022 sent the bill to a study order. Perhaps bars and restaurants will get some relief next year.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Time To Bring Back Happy Hour To Massachusetts?

This session the Massachusetts Legislature considered “An Act restoring happy hour to the commonwealth" SB.169 at the request of a group of Boston College Law School students. The bill would allow restaurants and bars to discount alcoholic beverages during specified times if drink prices are not changed during the happy hour; the happy hour does not take place after 10 pm; and notice of the happy hour is posted on the premises or website at least three days in advance.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

Massachusetts banned happy hour in 1984 as part of a national effort to combat drunk driving. Earlier that year President Reagan signed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 (23 U.S.C. § 158), which cut federal highway funds to states with drinking ages under 21. In 1985 there were 18,125 alcohol impaired crash fatalities, representing 41% of total traffic deaths in the country. At the behest of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Massachusetts joined several other states to restrict happy hours. Today, Massachusetts is one of eight U.S. states that still ban happy hours along with Alaska, Indiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

The 38-year effort against drunk driving has had a significant effect: by 2019 there were 10,142 drunk driving fatalities representing 28% of total traffic deaths. Today, AAA ranks Massachusetts first among all states for having the least severe drunk driving problem. However, it is unclear that happy hour restrictions contributed to this downward trend. For example, in 2015 Illinois legalized happy hours after a 26 year ban. According to Department of Transportation data, during 2014, the last year that happy hour was outlawed in Illinois, there were 353 alcohol-related traffic deaths—38% of all traffic fatalities. In 2019 there were 368 alcohol-related traffic deaths—36% of traffic fatalities. It appears doing away with the happy hour ban had little to no effect on alcohol impaired traffic deaths in the state. Other drunk driving measures such as the 21 year-old minimum drinking age, strict enforcement of drunk driving laws, and changing youth attitudes and behaviors surrounding drunk driving have played the largest role in the reduction in traffic deaths nationally. Still, a 2014 study found that college students greatly increased alcohol consumption during promotions and happy hours that decreased overall prices.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

An additional factor is that driving options have changed greatly since 1984. Today, ride share companies such as Uber and Lyft are now a popular and convenient way to get around after a night on the town. Since ride shares are fairly inexpensive during off-peak hours, it is more likely that people who had too much to drink would call an Uber rather than driving after happy hour ends. Additionally, parking in Boston is tedious and expensive at best. Finding parking in Boston reasonably close to a bar or restaurant—or reasonably priced—takes near herculean effort. Ride shares are often a more convenient and better economic option.

The bill's findings and purposes section lists both the law’s ineffectiveness and economic factors for lifting the ban. The bill claims restoring happy hour “will support local businesses, shift patronage of bars and restaurants toward low-density hours, and benefit the public morale.”

Indeed, offering happy hour specials could help restaurants and bars boost sales during off-peak hours. In the time of Covid-19, these discounts and specials could mitigate the losses suffered during the pandemic. Joshua Lewin, a co-owner of a restaurant in Somerville and Boston argued that in the time of Covid happy hours bring in patrons during slow times of the day. Happy hours spread out the times in which people go to the restaurants as allow social distancing measures.

The proposal is also popular; a recent MassINC poll found 70% of people approved lifting the happy hour ban with only 9% strongly opposed. In addition, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (“MADD”), one of the strongest proponents for prohibiting happy hours, does not currently have an official stance on lifting the ban due to the advent of ride shares as a safeguards against drunk driving.

Allowing happy hours, however, faces significant opposition. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker is skeptical about the bill stating, “That law did not come about by accident. It came about because there was a sustained series of tragedies that involved both young and older people, in some terrible highway incidents, all of which track back to people who’d been over-served as a result of happy hours in a variety of places... I’d be hard-pressed to support changing it.”

While drunk driving and binge drinking are still a concern, drunk driving incidents have been on the decline over the last twenty years. Evidence suggests the Massachusetts prohibition of happy hour is outdated and ineffective for decreasing drunk driving. The Commonwealth should refocus its efforts to curb drunk driving through increased education and outreach programs along with tighter enforcement across the Commonwealth. Further, the Legislature should support legislation that will aid local business in any way that is practical; happy hours would give bars and restaurants a boost while helping to manage the flow of customers.

At any rate, the bill seems to be done for the session. The committee on Consumer Protection and Professional Licensure held a hearing on August 30, 2021, and in January 2022 sent the bill to a study order. Perhaps bars and restaurants will get some relief next year.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Dane White anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

Ryan Platt anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2023.

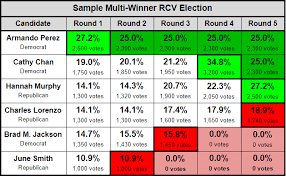

The Legality of Ranked Choice Voting

For a number of reasons, Jared Golden (D-ME) made national news when he was elected to represent Maine’s second congressional district (CD-2). First, CD-2 is roughly ten points more conservative than the nation as a whole and voted for former President Trump twice. Second, his victory meant the Democratic party would occupy all of New England’s House seats. Third, his election was the first time that CD-2 failed to elect an incumbent running for re-election in over 100 years. Finally, through the mechanics of Maine’s Rank-Choice Voting (RCV) system, Golden won despite initially having 2000 votes fewer than incumbent Bruce Poliquin. Poliquin filed a slew of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of RCV, but Golden was ultimately seated.

As more jurisdictions begin to consider implementing RCV, both state and federal courts will have to determine the legal contours of RCV. This blog post will briefly describe the history and mechanics of RCV before surveying the serious challenges RCV has faced and will continue to face at both the state and federal level.

What is RCV and How Did it End Up in Maine?

RCV is a voting system that allows voters to pick a preferred order of candidates for any given position. If one candidate is the first choice of more than 50% of the voters, they are the winner of the election. However, if no candidate successfully secures 50% of first-choice ballots, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Officials then conduct a new round of counting, redistributing votes for the eliminated candidate(s) based on each effected ballot’s second choice. The process repeats itself until one candidate has at least 50% of the vote.

Proponents of RCV claim that it improves voter turnout, minimizes negative campaigning, and increases faith in elections. It also prevents candidates from winning elections who are actively disliked by the majority of voters. With states often being the laboratories for legislative policy, Maine was an obvious choice for targeting passage. Maine has a long history of electing independent politicians or voting heavily for third party candidates. Between Independent Jim Longley’s victory in 1974 with only 39.7% of the vote and the enactment of RCV in 2016, only two governors have been elected with a majority of the vote.

Although Maine’s affinity for independent-minded politicians often results in politically moderate governors, Paul Lepage, a Tea Party favorite and self-proclaimed “Trump before Donald Trump became popular,” was elected in 2012 with 37% of the vote. With shocking disapproval numbers for the new governor, advocates pitched RCV as a way to preserve Maine’s unique history of voting for third-party candidates while also preventing unpopular figures from claiming the governorship. In 2016, voters passed an initiative implementing RCV for all elections.

Source of Constitutionality Concerns

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

One Person One Vote and Burdens on the Right to Vote

Article 1 Section 4 of the Constitution grants states broad discretion to choose “[t]he Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for [federal] Senators and Representatives”. Having a novel method of electing officials is not per se unconstitutional, so Poliquin’s lawsuit claimed that RCV violates the federal right to vote. He argued that voters whose initial preferences are eliminated get to vote more than once – once in the initial round, and again in each subsequent round where their second, third, or even fourth preference is counted. In Baber v. Dunlap (D. Me. 2018), Judge Lance E. Walker was not sympathetic. Judge Walker found that those who voted for Poliquin as their first choice had their votes counted just as much as those who voted for disqualified candidates and whose votes were distributed to second choices. Ultimately, he found that the process did not dilute or make irrelevant the votes listing Poliquin or Golden as a first choice.

Poliquin also argued that the Constitution requires the winners of federal offices to be determined by the plurality of the votes. Walker, a Trump appointee, found that Article I of the Constitution does not require states to declare winners based on the winner of the plurality vote: “There is no textual support for this argument and a great deal of historical support to undermine it.” For example, Judge Walker noted that several states require majority votes for elections through the use of run offs, yet these schemes have never been closely scrutinized under Article I. With respect to the plain text, Walker was equally unequivocal in his conclusion: “The framers knew how to distinguish between plurality and majority voting, and did so in other contexts in the Constitution, which leads to the sensible conclusion that they purposefully did not do so in Article I, section 2.”

Other jurisdictions have agreed RCV does not violate the Constitution. The 9th Circuit, ruling on San Francisco’s RCV scheme, stated “the City’s restricted [RCV] system is not analogous to limitations on voting in successive elections, because in San Francisco’s system, no voter is denied an opportunity to cast a ballot at the same time and with the same degree of choice among candidates available to other voters.” Thus, the weight of legal authority indicates that the Constitution does not prohibit states from implementing RCV.

State Constitutionality

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Conclusion

Following the Maine Supreme Court’s advisory opinion, the Maine legislature has tried to amend the state constitution to allow for RCV for state general election. Even if such efforts are successful in Maine, RCV faces challenges elsewhere. The Supreme Court of Alaska, the only other state with RCV, is heard a case on RCV’s constitutionality in January 2022. Meanwhile, voters in Massachusetts turned down RCV at the ballot box. Thus, RCV faces seriously political and legal hurdles to gaining widespread implementation.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Book Review: Fighting Political Gridlock

by David J. Toscano

University of Virgina Press, 2021

ISBN: 9780813946467 (hardcover)

Over the last few days, I had the chance to read David J. Toscano’s excellent new book Fighting Political Gridlock: How States Shape Our Nation and Our Lives. From the dust jacket:

In this profoundly polarized era, the nation has been transfixed on the politics of Washington and its seemingly impenetrable gridlock. Many of the decisions that truly affect people’s lives, however, are being made not on the federal level but in the states. Faced with Washington’s political standoff, state governments are taking action on numerous vital issues, often with greater impact on citizens and their communities than from any decision made in D.C. Despite this, few Americans really understand their state governments or the issues they address. In Fighting Political Gridlock, David Toscano reveals how the states are working around the impasse in Washington and how state policies are increasingly shaping society.

Many people are fed up with the seemingly hopeless nature of the federal government. There is a lack of cooperation not just on important issues like immigration, the environment, and tax law—but also existential threats to the Republic like the deadly January 6th attack on the Congress.

The state governments, however, are filling the void by functioning as they were intended. This was especially true when faced by the global pandemic and a Trump White House that both undermined the government’s response to Covid-19 and at times actively worked against the efforts of the states.

Still, many people don’t realize how important state governments are to their day-to-day lives. Part of the problem is many people do not understand the difference between state and federal government. When I worked for the Massachusetts Senate I would often field telephone calls demanding that my boss, “the Congresswoman,” do something about military spending or nuclear weapons. I would patiently explain that our office could work on many issues, but those were exclusively the job of the federal government. I am willing to bet a similar scenario plays out daily in every state capitol in the country.

This book is a terrific primer on how state governments work and respond to challenges. In Chapter 5, “Players on the Stage” David describes the roles of various state actors such as the governor and legislators. David points out that legislatures often do the heavy lifting in state government and can be the dominant government institution—leading to the Virginia saying that, “Governors come and go, but the legislature is forever.” He also discusses the growing power of the state attorneys general to affect state and national policy, and the special interests that are ever more involved in drafting legislation.

David also emphasizes that every state is different—due both to the state’s history and physical characteristics such as natural resources, and how the state has decided to govern itself. David discusses the first part in Chapter 4, “The Cards You Are Dealt,” and the later in Chapter 3, “State Constitutions Matter.” I find state constitutional law fascinating— states started enacting constitutions in 1776, and the early state constitutions were the model for the U.S. Constitution. The Massachusetts Constitution, written in 1780 by John Adams, remains the oldest in-force constitution in the world. The most recent state constitution, Rhode Island’s, was drafted in 1986. Alabama adopted its sixth constitution in 1901 and at 388,882 words it is the longest and most amended constitution on the planet. How the state organizes itself, splits power creating “checks & balances,” and which rights are protected all affect how the state addresses policy challenges.

Throughout Fighting Political Gridlock, David comes back to a recurring mantra, “states matter!” Often he makes his argument in the context of the pandemic, which has allowed some governors—from both parties—to show real leadership. He goes on to discuss in detail how states have chosen to take on the challenges of: education policy ( Chapter 7), criminal justice (Chapter 8), economic development (Chapter 9), health care policy (Chapter10), culture war issues—such as abortion, guns, and immigration (Chapter 11), and climate change (Chapter 13).

The most compelling chapter may be the conclusion, “Reimagining Civic Engagement.” He begins the chapter with the timeless Lincoln quotation from his First Inaugural Address:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break the bonds of our affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched as surely as they may be, by the better angels of our nature.

David discusses the decline of civility in our political discourse. Just as we need cooperation, office holders are no longer just talking past each other but actively yelling at each other. He writes,

Many observers believe that some of the nation’s answers will be found in civic engagement, though there are disputes about the actual meaning of the term. But one thing appears clear: some of the greatest opportunities we have for rejuvenation will involve governments closest to the people. The answers are more likely to be found in our localities and our states than at the federal level. And a key leadership challenge of our time involves lighting the spark and fueling the flame of productive engagement with the representatives who serve us at those levels.

He persuasively argues that civil engagement can be repaired with the following:

-

- Employ empathy, humility, and respect for disagreement as the basis of civility;

- Embrace the truth; reconciliation will follow;

- Reinforce the political guardrails to guide our path;

- Cultivate the disruption of dynamic listening; and

- Reject the paralysis of guilt and the straight jacket of saintliness.

David’s take on the subject is not just thoughtful, but inspiring.

David, a 25 year veteran of Virginia state and local government, is the right author for a book on why states matter and how they fight gridlock. He served as a city councilor and the Mayor of Charlottesville from 1994-1996. He was then elected to the Virginia House of Delegates representing the 57th District, which includes all of Charlottesville and parts of Albemarle County—the seat once held by Thomas Jefferson. He served as a delegate for 14 years, serving on the Commerce and Labor Committee, Courts of Justice Committee, Rules Committee, and the Transportation Committee. David also served on state commissions on such important topics as disability policy, alcohol safety, developing manufacturing and reviewing the state’s child support guidelines. For seven years, the Democratic Caucus elected David the House’s Democratic Leader. He left office in 2020, and now practices law with the Charlottesville firm Buck, Toscano & Tereskerz. Prior to entering public service, David received a BA from Colgate University, a Ph.D. in sociology from Boston College and a J.D. from the University of Virginia. He also writes a very interesting blog called Why States Matter.

I say David is the right author not just because of his extensive experience, but because of his attitude toward policy and politics. If legislators can be broken into work horses and show horses, David is clearly the former who cares about good public policy. David covers the policy choices made by states with the nuance and insight that comes from many years of hard legislative work. Second, although a Democrat with clear policy preferences, this book is not a one-sided argument for a partisan agenda. He is careful to give credit to officials from both parties where merited and criticism when criticism is due. This is very refreshing in a world where too many things read like a spin-doctor issued press release.

In an otherwise terrific book, one criticism is David consistently referred to Virginia as “the commonwealth.” This was confusing given that everyone knows that Massachusetts is the Commonwealth—and now we can both field criticism from the good people of Pennsylvania and Kentucky.

In an otherwise terrific book, one criticism is David consistently referred to Virginia as “the commonwealth.” This was confusing given that everyone knows that Massachusetts is the Commonwealth—and now we can both field criticism from the good people of Pennsylvania and Kentucky.

In addition, I was left wanting more from the chapter on civic engagement. David’s prescription for better civic engagement is compelling, but he does not describe how we can change public behavior. He is probably right that a successful effort will happen at the state and local levels, but there are several looming questions: How do we improve civic education? How can attitudes change when polite discourse and compromise are viewed as signs of weakness by large segments of the population? This problem will only grow as authoritarianism becomes more popular, polarization increases, and people live in media bubbles. In that vein, aren’t uncivil legislators just reflecting what their constituents want? What can the government do and what are its limits?

These are difficult questions, and I do not have answers. Perhaps David does and can write a follow-up book—I would be excited to read it.

Chaos

I bought a painting!

I am not a major collector by any means, but I could not pass this one up:

The painting, entitled "Chaos," is by Austin Texas based artist Laura Atlas Kravitz from Lollies Follies Studio. A lawyer, Laura works in government relations for an education organization. She started painting as a stress relief and a way to bring the community together. One of Laura's ongoing themes is the Texas State Capitol and how she sees it depending on the day, time of year, and perhaps most importantly, what is going on at the time.

The Texas State Capitol was constructed between 1882 and 1888 and has been a National Historic Landmark in 1986. The Capitol is located on a hilltop overlooking downtown Austin and is an example of Italian Renaissance Revival style. Although it is taller  than the US Capitol, it is only the sixth tallest state capitol, so there is at least one thing that isn’t bigger in Texas! Then again, the Capitol has almost 400 rooms and at 360,000 square feet of floor space, it is the largest state capitol in the United States.

than the US Capitol, it is only the sixth tallest state capitol, so there is at least one thing that isn’t bigger in Texas! Then again, the Capitol has almost 400 rooms and at 360,000 square feet of floor space, it is the largest state capitol in the United States.

The building has a pink hue because it is constructed of local sunset red granite. When the building was dedicated there was a weeklong celebration that included cattle roping, baseball games, singing groups, and fireworks. Some attendees purchased pieces of red granite as souvenirs.

The Capitol is topped with the statue Goddess of Liberty, a sculpture by Elijah E. Myers. In 1986, the original sculpture was replaced by a replica and the restored original is now in the The Bullock Texas State History Museum.

So why did I like this painting so much?

Anyone who has worked in Congress or a legislature knows the emotion that this painting evokes. Most of Laura’s other paintings of the Capitol (available on Etsy) are light, some with many colors. Here the Capitol is surrounded by darkness. This, however, is not the darkness of a clear Texas night where the Goddess of Liberty generously adds a star to the firmament. This is a gloomy, yet swirling, darkness that at once uproots the Capitol from its Austin hilltop but also weighs the Capitol down. The darkness churns, not from winds or storm, but from uncertainty.

Laura tells me she painted “Chaos” a few days into the Legislature’s Second Special Session --a very chaotic time. A group of House Democrats had decamped to Washington DC in an attempt to stop what they saw as an odious bill that would have restricted voting rights. In return, Governor Greg Abbot, in a cruel-yet predictable-move, vetoed funding for the legislature and its 2,100 employees. That is fine for the legislators themselves, who are paid very little for their service and stand for election for reasons other than financial gain. It was obnoxious, however, to threaten the legislative staff—the people who keep the Capitol clean, the ones who answer telephone calls from constituents, the legal and policy staff who draft and redraft the bills to be debated. This year, they were working special session after special session. Staff work long unpredictable hours with tremendous stress. Further, legislative staff, especially lawyers, are typically paid far less than what they could make in other jobs. In large part, they do their job out of a sense of public service. To threaten the staff and their families with no pay was unconscionable.

Some will blame the missing Democrats for the chaos. I generally believe that when someone is honored by their constituents to represent their community they have an obligation to be there. If you are going to break quorum, however, it should be over something vitally important—like protecting the voting rights of the powerless and underrepresented. The Republicans pushing these voting rules might point out that they control the Legislature and under our system the majority rules. True. Still, in a Constitutional system, the will of the majority is tempered--and sometimes thwarted--by the God-given rights of the minority. Efforts to protect someone's ability to vote, which is referred to as a right in the US Constitution no less than five times, is--or should be--an example of when extraordinary measures are required.

I really like that Laura used gold to define the Capitol rather than another color—especially the pink of the actual granite. Gold is not just valuable, but precious. Legislatures, both as an institution and as a concept, are precious as well--even in difficult, chaotic times. People peacefully debating to work out their differences and create policy for the greater good may be the most valuable thing ever devised by society. In this painting the gold is swirling off the building and into the gloom. Unlike red granite, gold is malleable and soft. It is easily molded into something beautiful; but items made of gold can just as easily be scratched, chipped away, or destroyed.

In times of chaos, the legislature can suffer—both in its reputation held by the people outside the building and in the faith and enthusiasm of the people within. Luckily, when the legislative body returns to normal and functions as it should, the precious gold luster can be both restored and augmented—in preparation for the next storm of chaos.

I will end my amateur art analysis by noting that the gloom in Laura's painting is not total--there are spots of light in the dark. Looking at the painting the light spots are amidst splotches that could have been caused by drops of sweat--or tears. Still, hope hides just beyond the chaos. The British poet Alfred Noyes wrote The Road Through Chaos, which begins:

There is one road, one only, to the Light:

A narrow way, but Freedom walks therein;

A straight, firm road through Chaos and old Night,

And all these wandering Jack-o-Lents of Sin.

It is the road of Law, where Pilate stays

To hear, at last, the answer to his cry;

And mighty sages, groping through their maze

Of eager questions, hear a child reply.

I have commissioned Laura for another painting of the Capitol on the theme of “Sine Die” when the session finally, mercifully comes to an end and the legislative business, for better or worse, concludes.

I can’t wait to see what she comes up with.

n.b. All opinions in this article are mine alone and do not reflect those of the artist.

Here Comes the Sun?

On March 12, 2021, a bipartisan coalition of Senators reintroduced the Sunshine Protection Act, a bill that would make daylight saving time permanent across the country. Leading sponsors include Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Marco Rubio (R-Fla.). This legislation would not only eradicate the disruption created by changing our clocks twice a year, but would also result in more afternoon and evening daylight for everyone around the country. This is not the first attempt to make daylight saving time permanent; bills to end the time changes have been introduced in Congress and in state legislatures with little success. A similar bill was introduced in the Senate in 2019. In 2019 and 2020, thirty-two states, including Massachusetts, proposed legislation to make daylight savings permanent.

Daylight Saving in the United States

Daylight saving was instituted in America during World War I. Germany became the first country to institute the change in 1916

Ohio Clock in the U.S. Capitol being turned forward for the first U.S. daylight saving time on March 31, 1918.

as a way to conserve fuel. England and America followed shortly after in 1918, believing that more daylight during the workday would reduce coal usage and thus save energy. Evidence that it saves energy is slim, however, as lighting has become increasing energy efficient.

President Woodrow Wilson wanted to keep daylight savings after the war ended, but anecdotally received pushback from farmers who would lose an extra hour of light in the morning. The darker mornings made it more difficult for them to get their products to market, and often negatively affected their livestock. It was eventually abolished, but then reinstated by President Roosevelt during World War II.

After World War II ended, states retained the power to decide whether to observe daylight saving time. In 1966, Congress enacted the Uniform Time Act for states that had chosen to observe daylight saving. The Act designated uniform dates on which daylight saving would begin, so as to prevent confusion in travel and broadcasting.

Let the Sunshine in

The time has come to make daylight saving permanent. Changing our clocks twice a year causes unnecessary stress and confusion, and losing valuable daylight in the dreary winter months is an unwelcome side effect.

First, research has shown that changing our clocks in the fall contributes to an increase in Seasonal Affective Disorder among the population. Scientists believe that shorter days and reduced sunlight in the winter trigger biochemical changes in the brain. Many have even suggested light therapy (exposure to a light box that simulates high-intensity sunlight) as treatment for depressive disorders. The effects of darkness on our mental health have only been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people who found solace in evening walks, exercising, or general outdoor time lost those outlets and motivation when they lost daylight in November. Making daylight saving permanent would improve our mental health by increasing opportunities to get sunlight every day, and by providing more time for healthy outdoor activities.

Second, eliminating time changes would have a number of other health and safety benefits. Aligning daylight with workers’ standard hours would increase visibility during busy driving times, helping prevent crashes. Additionally, research has shown that the number of car crashes spike in the week following the spring time change. Abolishing the change would eliminate the stress and confusion that accompanies sudden changes to work schedules. Furthermore, making daylight saving permanent would shift busy driving hours away from certain animals’ nocturnal hours, thereby reducing vehicle collisions with wildlife. Research has also suggested that transitions in and out of daylight saving time disrupt circadian rhythms and lead to increased risk for heart attacks and strokes. More daylight in the evenings also reduces your risk of being the victim of a robbery.

Second, eliminating time changes would have a number of other health and safety benefits. Aligning daylight with workers’ standard hours would increase visibility during busy driving times, helping prevent crashes. Additionally, research has shown that the number of car crashes spike in the week following the spring time change. Abolishing the change would eliminate the stress and confusion that accompanies sudden changes to work schedules. Furthermore, making daylight saving permanent would shift busy driving hours away from certain animals’ nocturnal hours, thereby reducing vehicle collisions with wildlife. Research has also suggested that transitions in and out of daylight saving time disrupt circadian rhythms and lead to increased risk for heart attacks and strokes. More daylight in the evenings also reduces your risk of being the victim of a robbery.