By Eli Oh

Closing Loopholes with New Whistlerblower Protection Legislation and Dispensing the View of Whistleblowers as Mere Disgruntled Employees

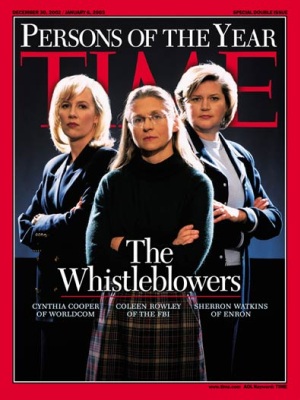

Following the havoc of corporate scandals caused by Enron, Worldcom, and Madoff and Stanford’s Ponzi scheme, instances of corporate fraud and whistleblowing is no longer a novel subject matter today. Accordingly, questions surrounding the extent of ethical responsibility of those employees ancillary to the fraud emerged but with no clear answer. Blowing the whistle on one’s own employer certainly appears to be a violation of loyalty and other fiduciary obligations, while on the other hand, whistleblowers serve an important function in enforcing corporate compliance. Retaliation often follows and whistleblowers are inevitably in need of legal protection. These two interests collide head on, leaving open a number of questions as to the nature of an employee’s fiduciary duty, the policy rationales for protecting whistleblowers and the approach that the law must take. In the meantime, with the rise of litigation involving whistleblowers in recent years, there has been movement in Congress to enact a new statute that will further expand whistleblower protection and close loopholes in current legislation, particularly in the financial and banking industry.

Background of Whistleblower Legislation

Among others, Congress enacted three notable statutes to protect whistleblowers from retaliation: the Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

The Whistleblower Protection Act (“WPA”) was enacted in 1989 by the 101st Congress which took the foundation laid by the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 and expanded the provisions to increase protection for whistleblowers. The WPA forbids the federal government from reprisal against federal government employees for blowing the whistle and encourages employees to report wrongful conduct of federal government employers by means of monetary awards. The WPA remains the primary federal statute that guarantees federal employees whistleblower protection, although, under this statute private sector employees do not have standing for a cause of action.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (“SOX Act” or “the Act”), promulgated in 2002 in response to the Enron and WorldCom debacle, significantly expanded the scope of whistleblower protection and increased regulation of businesses in order to deter and detect fraud, particularly corporate and securities fraud. The statute reaches employees in the private sector, particularly those employed by publicly held companies. It was one of the “first set of comprehensive federal whistleblower provisions protecting employees who raise concerns about a violation of any federal criminal statute.”

In spite of the enactment of the SOX Act, which was hailed at the time as one of the most comprehensive bodies of law enacted to deter and prevent corporate malfeasance, another series of corporate fraud mayhem, most notably the fifty billion dollar Ponzi scheme perpetrated by Madoff and Stanford, in addition to the 2008 financial crisis, caused Congress to pass the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010 (“Dodd-Frank Act” or the Act”). The purpose of the statute was clearly to deter corporate malfeasance as well as other illegal business practices. In the process, the Dodd-Frank Act broadened whistleblower protection even further beyond the bounds of the SOX Act by expanding whistleblower protection to beyond public companies and by increasing monetary incentives to report perpetration of fraud to government agencies.

Nonetheless, the Dodd-Frank Act is not without loopholes. Among others, the statute does not expressly provide for individual liability nor defines the term “employer.” This leaves open an interpretation strongly suggesting inapplicability of the anti-retaliation provisions to individuals. It also leaves open the definition of “covered employee” who may be entitled to whistleblower protection, which makes room for arguments for varying interpretations and perhaps more litigation. Furthermore, the statute is silent regarding the enforceability of non-disclosure agreements that restrict the employees from disclosing confidential information or present employees with a waiver of their protected rights under whistleblower legislation. In practice, some companies have internally disciplined whistleblowers for communications with the government.

Latest Statistics

In practice, during the last decade, whistleblowing cases received have increased in significant numbers. In 2005, cases filed by complainants under various agencies and statutes including the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (“OSHA”), Sarbanes Oxley Act (“SOX”), and the Surface Transportation Assistance Act (“STAA”) totaled 1934; by 2015, this number climbed to 3288. What is notable is that amongst the dramatic increase of complaints, the rates of positive outcomes have stayed relatively steady. Out of the total number of cases received in 2005, 20 percent counted for positive outcomes for complainants while 66 percent of cases were dismissed. In 2015, the positive outcome for complainants amounted 25 percent of all cases and 50 percent of total cases received were dismissed. It is also notable that despite a significant increase in the total number of cases received, the number of cases given merit have stayed roughly the same. Out of 1902 cases in 2005, 41 cases were given merit. However, in 2015, out of 3337 cases, only 45 cases were given merit. Most of the positively regarded outcomes were settled. Thus, generally, in enforcing the 22 whistleblower statutes, OSHA dismissed a fair number of cases received and a very small percentage of the claims have been given merit. It is apparent that in spite of the increased frequency of whistleblowing, complainants are still predominantly viewed as mere disgruntled employees that dispose their loyalty rather than those internally convicted to adhere to their personal ethical standards.

New Legislation

On February 25, 2016 Representative Cummings and Senator Baldwin submitted H.R. 4619 and S.2591 also known as Whistleblower Augmented Reward and Non-Retaliation (WARN) Act in order to “to provide heightened protections for those who blow the whistle on suspected financial misconduct.” The sponsors of the bill said in a press release that the legislation is “to combat retaliation against whistleblowers and to close loopholes in the DoddFrank Act relied upon by Wall Street giants.” The new statute will increase whistleblower protection by expanding whistleblower protections and providing additional legal procedures for such protections. The bill attempts to do this by prohibiting employers from “forcing whistleblowers to waive their rights or disclose their communications with the government; safeguard whistleblowers from retaliation if they refuse to participate in activities they believe to be in violation of the law”; harmonize whistleblower awards under the Dodd-Frank Act with other relevant statutes so that whistleblowers are “eligible to receive between 10 percent and 30 percent of penalties and recoveries”; apply additional “procedures, evidentiary standards, and burdens of proof” allowing whistleblower to show that their actions led to unfavorable personnel actions.

The WARN Act is endorsed by Americans for Financial Reform, the AFL-CIO and the Communication Workers of America, and other organizations. So far, there has been no notably strong opposition to the bill since it has been referred to the Subcommittee on Commodity Exchanges, Energy, and Credit. Although the bill proposes some changes that are rather drastic and thus proponents of the bill expect some opposition that may find the bill extremely employee-friendly, they believe this to be “good legislation” that will improve whistleblower protection.