The Legality of Ranked Choice Voting

For a number of reasons, Jared Golden (D-ME) made national news when he was elected to represent Maine’s second congressional district (CD-2). First, CD-2 is roughly ten points more conservative than the nation as a whole and voted for former President Trump twice. Second, his victory meant the Democratic party would occupy all of New England’s House seats. Third, his election was the first time that CD-2 failed to elect an incumbent running for re-election in over 100 years. Finally, through the mechanics of Maine’s Rank-Choice Voting (RCV) system, Golden won despite initially having 2000 votes fewer than incumbent Bruce Poliquin. Poliquin filed a slew of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of RCV, but Golden was ultimately seated.

As more jurisdictions begin to consider implementing RCV, both state and federal courts will have to determine the legal contours of RCV. This blog post will briefly describe the history and mechanics of RCV before surveying the serious challenges RCV has faced and will continue to face at both the state and federal level.

What is RCV and How Did it End Up in Maine?

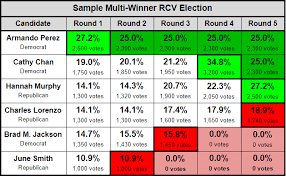

RCV is a voting system that allows voters to pick a preferred order of candidates for any given position. If one candidate is the first choice of more than 50% of the voters, they are the winner of the election. However, if no candidate successfully secures 50% of first-choice ballots, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Officials then conduct a new round of counting, redistributing votes for the eliminated candidate(s) based on each effected ballot’s second choice. The process repeats itself until one candidate has at least 50% of the vote.

Proponents of RCV claim that it improves voter turnout, minimizes negative campaigning, and increases faith in elections. It also prevents candidates from winning elections who are actively disliked by the majority of voters. With states often being the laboratories for legislative policy, Maine was an obvious choice for targeting passage. Maine has a long history of electing independent politicians or voting heavily for third party candidates. Between Independent Jim Longley’s victory in 1974 with only 39.7% of the vote and the enactment of RCV in 2016, only two governors have been elected with a majority of the vote.

Although Maine’s affinity for independent-minded politicians often results in politically moderate governors, Paul Lepage, a Tea Party favorite and self-proclaimed “Trump before Donald Trump became popular,” was elected in 2012 with 37% of the vote. With shocking disapproval numbers for the new governor, advocates pitched RCV as a way to preserve Maine’s unique history of voting for third-party candidates while also preventing unpopular figures from claiming the governorship. In 2016, voters passed an initiative implementing RCV for all elections.

Source of Constitutionality Concerns

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

In the five years since Maine voters passed RCV, opponents have levied a number of legal attacks against RCV. These attacks have typically followed two main theories: that the system violates the federal ‘one person one vote’ doctrine, or that it runs afoul of state constitutional language that implies the winner of an election need not have a majority of the vote.

One Person One Vote and Burdens on the Right to Vote

Article 1 Section 4 of the Constitution grants states broad discretion to choose “[t]he Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for [federal] Senators and Representatives”. Having a novel method of electing officials is not per se unconstitutional, so Poliquin’s lawsuit claimed that RCV violates the federal right to vote. He argued that voters whose initial preferences are eliminated get to vote more than once – once in the initial round, and again in each subsequent round where their second, third, or even fourth preference is counted. In Baber v. Dunlap (D. Me. 2018), Judge Lance E. Walker was not sympathetic. Judge Walker found that those who voted for Poliquin as their first choice had their votes counted just as much as those who voted for disqualified candidates and whose votes were distributed to second choices. Ultimately, he found that the process did not dilute or make irrelevant the votes listing Poliquin or Golden as a first choice.

Poliquin also argued that the Constitution requires the winners of federal offices to be determined by the plurality of the votes. Walker, a Trump appointee, found that Article I of the Constitution does not require states to declare winners based on the winner of the plurality vote: “There is no textual support for this argument and a great deal of historical support to undermine it.” For example, Judge Walker noted that several states require majority votes for elections through the use of run offs, yet these schemes have never been closely scrutinized under Article I. With respect to the plain text, Walker was equally unequivocal in his conclusion: “The framers knew how to distinguish between plurality and majority voting, and did so in other contexts in the Constitution, which leads to the sensible conclusion that they purposefully did not do so in Article I, section 2.”

Other jurisdictions have agreed RCV does not violate the Constitution. The 9th Circuit, ruling on San Francisco’s RCV scheme, stated “the City’s restricted [RCV] system is not analogous to limitations on voting in successive elections, because in San Francisco’s system, no voter is denied an opportunity to cast a ballot at the same time and with the same degree of choice among candidates available to other voters.” Thus, the weight of legal authority indicates that the Constitution does not prohibit states from implementing RCV.

State Constitutionality

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Upon Maine’s enactment of RCV, the Maine senate asked the Maine Supreme Court for an advisory opinion on RCV’s constitutionality. Specifically, the Senate President was concerned about the state constitution’s language requiring the winners of state positions to be determined by a “plurality of all the votes.” In their opinion, the Court recognized that although citizen-enacted laws enjoy a “heavy presumption” of constitutionality, “the language of the Maine Constitution . . . is clear.” The Court found clarity particularly in light of the history of the Constitution’s text – which was changed to the current language after a series of run-off elections caused confusion, anger, and a violent confrontation on the steps of the state house in 1879. Out of respect for this history, the Justices believed they had no choice but to avoid any construction that failed to seat any state office candidate winning the plurality of the vote. Thus, even though RCV can be used for federal elections and all primaries in Maine, it may not be utilized in the general elections for state positions.

Conclusion

Following the Maine Supreme Court’s advisory opinion, the Maine legislature has tried to amend the state constitution to allow for RCV for state general election. Even if such efforts are successful in Maine, RCV faces challenges elsewhere. The Supreme Court of Alaska, the only other state with RCV, is heard a case on RCV’s constitutionality in January 2022. Meanwhile, voters in Massachusetts turned down RCV at the ballot box. Thus, RCV faces seriously political and legal hurdles to gaining widespread implementation.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.

Spencer Shagoury anticipates graduating from Boston University School of Law in May 2022.