Spring 2023 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy

Spring 2023 lectures will be presented either in-person or via webinar format, no hybrid events this term. Registration is free and open to the public – please follow the link for each program to register.

Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafes, and Coffeehouses with Alex Ketchum

Since 2018, Dr. Alex Ketchum has been the Faculty Lecturer of the Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies of McGill University. She is the Director of the Just Feminist Tech and Scholarship Lab and the organizer of Disrupting Disruptions: The Feminist and Accessible Publishing, Communications, and Tech Speaker and Workshop Series. Her work integrates food, environmental, technological, and gender history. Ketchum's first peer-reviewed book, Engage in Public Scholarship!: A Guidebook on Feminist and Accessible Communication (Concordia University Press, 2022), examines the power dynamics that impact who gets to create certain kinds of academic work and for whom these outputs are accessible. Coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of the trailblazing restaurant Mother Courage of New York City, Ketchum's second book, Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafes, and Coffeehouses (2022), is the first history of the more than 230 feminist and lesbian-feminist restaurants, cafes, and coffeehouses that existed in the United States from 1972 to the present.

Ketchum's interest in past imaginings of utopia through business creation and the implementation of communications technologies has guided her new research and third book project on historically contextualizing the relationship between feminist ethics and AI. You can find out more about her other writings, podcasts, zines, exhibitions, and more at alexketchum.ca.

Date & Time:

Tuesday, February 28, 2023, 6 pm EST

Location: Demo Kitchen

Groce Pépin Culinary Innovation Lab

808 Commonwealth Ave. Room 124

Watch the recording of Ingredients for Revolution here:

How the Other Half Eats: The Untold Story of Food and Inequality in America with Priya Fielding-Singh

An “illuminating” (New York Times) and “deeply empathetic” (Publishers Weekly, starred review) “must-read” (Marion Nestle) that “weaves lyrical storytelling and fascinating research into a compelling narrative” (Chronicle Review) to examine nutrition inequities in America, illuminating exactly how inequality starts on the dinner plate.

Inequality in America manifests in many ways, but perhaps nowhere more than in how we eat. From her years of field research, sociologist and ethnographer Priya Fielding-Singh brings us into the kitchens of dozens of families to explore how—and why—we eat the way we do. By diving into the nuances of these families’ lives, Fielding-Singh lays bare the limits of efforts narrowly focused on improving families’ food access. Instead, she reveals how being rich or poor in America impacts something even more fundamental than the food families can afford: these experiences impact the very meaning of food itself.

Packed with lyrical storytelling and groundbreaking research, as well as Fielding-Singh’s personal experiences with food as a biracial, South Asian American woman, How the Other Half Eats illuminates exactly how inequality starts on the dinner plate. Once you’ve taken a seat at tables across America, you’ll never think about class, food, and public health the same way again.

Dr. Fielding-Singh is a sociologist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Consumer Studies at the University of Utah.

Date & Time:

Friday March 24, 2023, 12pm (noon) EDT

Location: Virtual- via Zoom

(link will be sent to ticketed attendees one day prior to the lecture)

Please visit our Eventbrite page here for tickets and event information.

Grain and Fire: A History of Baking in the American South with Rebecca Sharpless

While a luscious layer cake may exemplify the towering glory of southern baking, like everything about the American South, baking is far more complicated than it seems. Rebecca Sharpless here weaves a brilliant chronicle, vast in perspective and entertaining in detail, revealing how three global food traditions—Indigenous American, European, and African—collided with and merged in the economies, cultures, and foodways of the South to create what we know as the southern baking tradition.

Recognizing that sentiments around southern baking run deep, Sharpless takes delight in deflating stereotypes as she delves into the surprising realities underlying the creation and consumption of baked goods. People who controlled the food supply in the South used baking to reinforce their power and make social distinctions. Who used white cornmeal and who used yellow, who put sugar in their cornbread and who did not had traditional meanings for southerners, as did the proportions of flour, fat, and liquid in biscuits. By the twentieth century, however, the popularity of convenience foods and mixes exploded in the region, as it did nationwide. Still, while some regional distinctions have waned, baking in the South continues to be a remarkable, and remarkably tasty, source of identity and entrepreneurship.

Dr. Sharpless is a professor of history at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, TX.

Date & Time:

Thursday, April 13, 2023, 6 pm EDT

Location:

School of Hospitality Administration- Room 110

928 Commonwealth Avenue Boston, MA 02215

(in-person only)

Please visit our Eventbrite page here for tickets and event information.

We kindly thank the Jacques Pépin Foundation for sponsorship of this lecture series.

New Students for Spring 2023, part 2

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Karina English was born to immigrant parents from Panama and El Salvador, and it was these multicultural and multiracial roots that introduced her to many flavors at a young age. She developed a love for food while watching her parents cook meals that spanned across continents. She gained her basic cooking skills in high school while working in several restaurants. She continued honing her skills as she attended Culinary School in Vail, Colorado, under the instruction of some of the nation’s top chefs. During culinary school, she answered the call to serve her nation in the United States Air Force, supporting important missions such as Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. During her service, she traveled the world tasting new flavors, learning new skills, and working in diverse environments further expanding her knowledge of food.

Karina English was born to immigrant parents from Panama and El Salvador, and it was these multicultural and multiracial roots that introduced her to many flavors at a young age. She developed a love for food while watching her parents cook meals that spanned across continents. She gained her basic cooking skills in high school while working in several restaurants. She continued honing her skills as she attended Culinary School in Vail, Colorado, under the instruction of some of the nation’s top chefs. During culinary school, she answered the call to serve her nation in the United States Air Force, supporting important missions such as Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. During her service, she traveled the world tasting new flavors, learning new skills, and working in diverse environments further expanding her knowledge of food.

After leaving the Air Force, Karina earned her BA in Small Business Management and Entrepreneurship. She then ventured into different fields such as urban farming, fashion design, and administration all while raising her large family. When COVID hit and the schools transitioned to online learning, she and her husband decided to homeschool their 5 children. During this time, she began teaching her children cooking skills, the importance of food, and food origins. There was no curriculum to follow, therefore she created her own. She felt that this information was essential for every child to learn so she decided to write a curriculum that would be available to everyone.

When not researching recipes and food origins, you will find Karina traveling around Arizona with her family, at a local farmers market, or car shows. She can’t wait to take a deeper dive into the study of food and learn from some great industry professionals.

♦♦♦♦♦

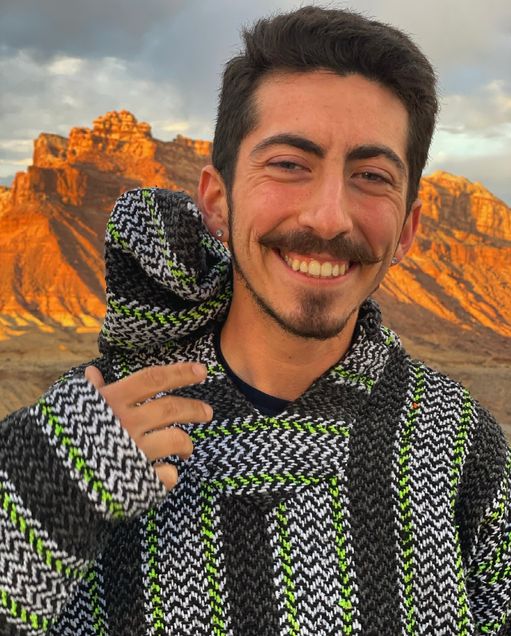

Alexander Milles (He/Him/They/Them) was taught by his mother that the best thing in life is good food paired with great company and laughter. He started Boifood, a food and travel blog in 2016, which led to work trips to Anaheim to attend Natural Products Expo West, and Seattle to attend Anthony's Oyster Festival, this last year. He currently lives in Boise, Idaho. In his free time he runs The Table Rock Podcast all about the local Treasure Valley food scene and Knead to Know Book Club which puts food at the center. He is a huge food insecurity advocate. Alex has been featured in local publications such as NPR's Idaho Matters and KTVB's Idaho Today. Alex has a B.S. in Advertising from the University of Idaho. He also has family in Springfield, Massachusetts. Fun fact, he's originally from Hawaii.

Alexander Milles (He/Him/They/Them) was taught by his mother that the best thing in life is good food paired with great company and laughter. He started Boifood, a food and travel blog in 2016, which led to work trips to Anaheim to attend Natural Products Expo West, and Seattle to attend Anthony's Oyster Festival, this last year. He currently lives in Boise, Idaho. In his free time he runs The Table Rock Podcast all about the local Treasure Valley food scene and Knead to Know Book Club which puts food at the center. He is a huge food insecurity advocate. Alex has been featured in local publications such as NPR's Idaho Matters and KTVB's Idaho Today. Alex has a B.S. in Advertising from the University of Idaho. He also has family in Springfield, Massachusetts. Fun fact, he's originally from Hawaii.

♦♦♦♦♦

Noel Motsinger was born in Minnesota and was never a big fan of food. She did spend hours at the dinner table as a young child, but it was usually in protest over having to finish her creamed corn or baked beans. She has no charming stories of learning to cook at someone’s knee. Her mom served solid Midwestern favorites like sloppy joes, meatloaf, spaghetti sauce loaded with mushrooms, and that special Minnesota peculiarity called “hot dish.” Noel didn’t like any of those things.

Noel Motsinger was born in Minnesota and was never a big fan of food. She did spend hours at the dinner table as a young child, but it was usually in protest over having to finish her creamed corn or baked beans. She has no charming stories of learning to cook at someone’s knee. Her mom served solid Midwestern favorites like sloppy joes, meatloaf, spaghetti sauce loaded with mushrooms, and that special Minnesota peculiarity called “hot dish.” Noel didn’t like any of those things.

At some point she changed from being a child indifferent for food to an adult who learned how to feed herself, learned to do it well, and realized she enjoyed it. She spends most of her free time reading cookbooks, especially vintage ones, and collecting odd volumes during her travels with her archaeologist husband.

Noel earned her bachelor’s degree in Hospitality Administration from Florida State. Her career history includes time in the hospitality industry, Title IV student financial aid regulatory compliance, and cultural resource management.

Noel is looking forward to being part of this community and, having spent the last 14 years working with anthropologists, exploring the interface between people and food and culture as one of the most interesting aspects of life.

♦♦♦♦♦

Natalie Rivera Rivera, born and raised in Puerto Rico, has always been a curious and passionate person. Ever since she could remember, she has been interested in the concept of food and how it gathers people together. Being part of a big family, with almost 140 relatives, where every activity or reunion is focused around food gave her a unique perspective towards it. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until she went to university that the idea of understanding other countries by the way they communicate and interact with others sparked a curiosity in her. As a result, she obtained a bachelor’s degree at the University of Puerto Rico: Rio Piedras Campus in marketing and foreign languages: French and Italian. After that chapter, her passionate side led her to study baking and pastry arts at the Culinary Institute of America and a study abroad program in Puglia, Italy, where the concepts of food and culture collided, opening a whole new point of view to understanding history through food. In search of her cultural identity, the interwoven concepts of culture, language, and food became the inspiration for her learning and preserving Puerto Rico’s food history and representing it through bread and pastries.

Natalie Rivera Rivera, born and raised in Puerto Rico, has always been a curious and passionate person. Ever since she could remember, she has been interested in the concept of food and how it gathers people together. Being part of a big family, with almost 140 relatives, where every activity or reunion is focused around food gave her a unique perspective towards it. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until she went to university that the idea of understanding other countries by the way they communicate and interact with others sparked a curiosity in her. As a result, she obtained a bachelor’s degree at the University of Puerto Rico: Rio Piedras Campus in marketing and foreign languages: French and Italian. After that chapter, her passionate side led her to study baking and pastry arts at the Culinary Institute of America and a study abroad program in Puglia, Italy, where the concepts of food and culture collided, opening a whole new point of view to understanding history through food. In search of her cultural identity, the interwoven concepts of culture, language, and food became the inspiration for her learning and preserving Puerto Rico’s food history and representing it through bread and pastries.

Welcome New Students – Spring 2023

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Jadel Myra Biteng (She/They)- Jadel has always been surrounded by food and the love of food for as long as she can remember. Having been raised by her grandmother, who was a farmer and a cook, Jadel naturally grew up to become interested in the world of food herself.

Jadel Myra Biteng (She/They)- Jadel has always been surrounded by food and the love of food for as long as she can remember. Having been raised by her grandmother, who was a farmer and a cook, Jadel naturally grew up to become interested in the world of food herself.

After working in numerous restaurants/bakeries, she saw firsthand how COVID affected the restaurant industry. Spending the better half of the pandemic making food for the community, packing, delivering fresh groceries for homebound Asian elders and baking goods for free food fridges in NYC. Jadel really believes that food heals and everyone should have access to nutritious food. The system itself is broken but how we fix it and/or make it better is one of her main focuses.

Jadel is now seeking to gain the knowledge and background to be able to share more about this industry she called home for over 15 years. She hopes to gain strong connections and concrete opportunities with like-minded folks. To tackle meaningful issues that will ultimately lead her to a position where she can help push the industry that always made room for people like her to push forward.

Jadel currently works as baker, where they use freshly milled, traceable and locally sourced grains and flours. Jadel can always be found either reading up on her favorite food history magazine, Eaten, or cooking new recipes, eating with friends, and drinking a good glass of wine.

♦♦♦♦♦

Chef Robert Danhi has dedicated the past three decades researching, codifying, preserving, and sharing the cultures of Southeast Asia. Robert worked his way up from dishwasher to executive chef in restaurants and attended the Culinary Institute of America. Teaching culinary arts became his passion including a Chef Instructor at the CIA and Director of Education at the Southern California School of Culinary Arts. Chef next evolved into an R&D chef, industry thought leader, conference speaker and full-time consultant since 2005.

Chef Robert Danhi has dedicated the past three decades researching, codifying, preserving, and sharing the cultures of Southeast Asia. Robert worked his way up from dishwasher to executive chef in restaurants and attended the Culinary Institute of America. Teaching culinary arts became his passion including a Chef Instructor at the CIA and Director of Education at the Southern California School of Culinary Arts. Chef next evolved into an R&D chef, industry thought leader, conference speaker and full-time consultant since 2005.

This curator of cultures is a James Beard award winning publisher, author and photographer for Southeast Asian Flavors-Adventures in Cooking the Foods of Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia & Singapore. His most recent book Easy Thai Cooking showcases simple recipes that result in the genuine flavors of Thailand.

Robert continued to share his passion and knowledge as the host of the 26-episode docuseries, Taste of Vietnam leads the global audience through 19 provinces of the vibrant lives of farmers, artisans, cooks, chefs, and street food vendors. The Vietnamese community then welcomed chef to be a main judge for all episodes of Season 1 of Top Chef Vietnam.

His latest project beginning in 2015 was founding and building Flavor360, a mobile app and interactive database for capturing structured multimedia culinary heritage research data. Robert’s next chapter includes joining the gastronomy program at Boston university and rebuilding Flavor360 as an open-sourced platform to connect support a global community of food studies researchers, journalists, culinarians, and students

When not exploring food cultures around the globe Robert splits his time between Los Angeles and his home in Melaka with his Malaysian born wife and best friend.

♦♦♦♦♦

For over fifteen years, Crystal Black-Davis has had the privilege to work as both an executive and an entrepreneur within various sectors of the food industry. Crystal’s fascination with gastronomy began as a child, in 1980s Indianapolis, after eagerly flipping through the pages of Food & Wine Magazine every month. Her father received the magazine as a free subscription for being an American Express cardholder but had little interest in the publication. Upon overhearing him mention to her mother that he planned to cancel the subscription, Crystal begged him not to. Surprised to learn that someone in the house was actually reading and enjoying the magazine, he decided to maintain the subscription. Crystal has been obsessed with food, specifically global cuisine, ever since.

For over fifteen years, Crystal Black-Davis has had the privilege to work as both an executive and an entrepreneur within various sectors of the food industry. Crystal’s fascination with gastronomy began as a child, in 1980s Indianapolis, after eagerly flipping through the pages of Food & Wine Magazine every month. Her father received the magazine as a free subscription for being an American Express cardholder but had little interest in the publication. Upon overhearing him mention to her mother that he planned to cancel the subscription, Crystal begged him not to. Surprised to learn that someone in the house was actually reading and enjoying the magazine, he decided to maintain the subscription. Crystal has been obsessed with food, specifically global cuisine, ever since.

Crystal is the former EVP (US) for the Italian-based CPG brand, Loacker, the global category leader in wafer confections. She currently owns Savvy Food consulting, advising early-stage and import CPG brands on market readiness, and consulting commodities importers on new market opportunities. Crystal has recently partnered with web3 venture studio, ZK Ladder, to explore how technology can disrupt broken food systems.

Crystal has been featured in notable media outlets such as Fast Company, Food Navigator, ABC7 New York, and Candy Industry Magazine for her industry insights and expertise. Crystal is an avid supporter of the UN World Food Programme, No Kid Hungry, Food Bank for New York City, and MoFAD (Museum of Food and Drink). Crystal is a mainstay at key food events such as the James Beard Awards (chef and media), Smithsonian Julia Child Award, Natural Products Expos (West and East), Fancy Food Show (Winter and Summer), SIAL (Paris), and ISM (Cologne).

Crystal has received numerous honors and awards from organizations including the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce and Path to Purchase Institute.

Fun fact, the best meal that Crystal has ever eaten was speck dumpling soup and radicchio ravioli at Patscheider Hof in Renon, Italy (Italian Alps).

♦♦♦♦♦

John Curran is a life-long resident of the Greater Boston area. While John’s professional career is not food related, he spends most of his free time cooking for his family and learning, formally and informally, about food. He has completed many adult education programs, including classes in classic European cooking and baking, the cuisine of China, American regional cooking, whole-hog butchery, and cheese production. Most recently, John earned his certificate in Culinary Arts from Bunker Hill Community College. This year-long program consisted of classroom lectures on topics such as sanitation, menu planning, and food purchasing, as well as significant hands-on kitchen instruction in baking and cooking.

John Curran is a life-long resident of the Greater Boston area. While John’s professional career is not food related, he spends most of his free time cooking for his family and learning, formally and informally, about food. He has completed many adult education programs, including classes in classic European cooking and baking, the cuisine of China, American regional cooking, whole-hog butchery, and cheese production. Most recently, John earned his certificate in Culinary Arts from Bunker Hill Community College. This year-long program consisted of classroom lectures on topics such as sanitation, menu planning, and food purchasing, as well as significant hands-on kitchen instruction in baking and cooking.

John is excited to learn from the distinguished faculty and his fellow students in the Gastronomy program at Boston University. His goal is to wed this knowledge with his thirty years of advocacy experience as a trial attorney, to positively influence Federal, State, and local food policy and legislation. He is particularly interested in the laws regarding agricultural land use, sustainability, and the distribution of healthy foods, and how legislation can be drafted, or modified, to better serve the public, generally, and those in food insecure communities, specifically.

John has been married to his college sweetheart, Maria, for thirty-one years. They are especially proud of their three children who have gone on to careers as a teacher, an eye doctor, and a soon-to-be lawyer. On weekends, you can usually find John, undeterred by the New England weather, in the backyard at his kamado grill.

♦♦♦♦♦

As an incoming Gastronomy master’s student, Hilary Landa is interested in exploring the role that food systems play in environmental, socioeconomic, and health issues and examining how food products/experiences affect how communities connect, build local economies, and solve problems.

As an incoming Gastronomy master’s student, Hilary Landa is interested in exploring the role that food systems play in environmental, socioeconomic, and health issues and examining how food products/experiences affect how communities connect, build local economies, and solve problems.

Thus far in her academic and professional career, she has focused on how communications and media can be leveraged to shift cultural norms and drive social change. Currently a Campaign Director at The Ad Council, she has managed fifteen national, integrated public service advertising campaigns concerning social issues like immigrant inclusion, recycling, and emergency preparedness.

While each issue she has worked on is important, the one that sparked her deep interest in food issues was Save The Food, a campaign in partnership with the Natural Resources Defense Council meant to increase Americans’ awareness of the impacts of wasted food and empower them to waste less in their own homes. Through working on Save The Food, she learned how food can be a mechanism to bridge divides and engage people around increasingly urgent issues like climate change, migration, and social cohesion. Additionally, working on this issue completely transformed her relationship with food and inspired her to become an avid cook and baker.

She can’t wait to build upon this foundation of knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of all aspects of the food field alongside other food enthusiasts in the Gastronomy program.

Hilary is a Californian at heart, but currently lives in Washington D.C. with her partner and cat. She has a B.A. in Public Policy from Duke University.

♦♦♦♦♦

Erik Lucas grew up on Long Island surrounded by food and people who loved to eat. Shortly after getting his BA in Theatre Arts at Fordham University at Lincoln Center, he attended culinary school at The Natural Gourmet Institute in NYC. That led to over 15 years working in food and beverage as a cook, chef, manager, event planner, and culinary director. He is excited to continue to explore interests in the intersection of food and culture, local food systems, food justice, and how we share our stories and histories through food. When not trying out a new recipe in his home kitchen, he loves exploring new areas and sampling the regional cuisine or popular local spots. Erik currently resides in Ithaca, NY and he greatly enjoys the local bounty of the Finger Lakes region. He lives with his wife, two children, cats, and a dog. When not cooking or eating he enjoys reading, film, and being out in nature.

Erik Lucas grew up on Long Island surrounded by food and people who loved to eat. Shortly after getting his BA in Theatre Arts at Fordham University at Lincoln Center, he attended culinary school at The Natural Gourmet Institute in NYC. That led to over 15 years working in food and beverage as a cook, chef, manager, event planner, and culinary director. He is excited to continue to explore interests in the intersection of food and culture, local food systems, food justice, and how we share our stories and histories through food. When not trying out a new recipe in his home kitchen, he loves exploring new areas and sampling the regional cuisine or popular local spots. Erik currently resides in Ithaca, NY and he greatly enjoys the local bounty of the Finger Lakes region. He lives with his wife, two children, cats, and a dog. When not cooking or eating he enjoys reading, film, and being out in nature.

♦♦♦♦♦

William Purdy (he/him) was raised in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Growing up he never showed much interest in food. In fact, his love of food wouldn’t show until he was about 23 years old. During his undergraduate career, he majored in health studies and discovered a passion for nutrition, learning as much as he possibly could. Eventually, this led to cooking and baking more, as well as helping friends and family make healthier food choices. He began baking bread and cooking all the time, trying new recipes and even attempting to make his own. Now, he cooks nearly every day for him and his partner. He loves trying new things in the kitchen. Recently discovering a fondness for making hot sauce, one his favorite condiments. His favorite foods to make include bread, pasta, and anything spicy. He spent a couple years working as a barista and discovered a whole new world of coffee. He loves going to new coffee shops and making coffee at home. When he is not cooking, you can find him reading, watching movies, or playing board games with friends and family. His love of film is just as strong as his love of movies. His favorite film is Pan’s Labyrinth.

William Purdy (he/him) was raised in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Growing up he never showed much interest in food. In fact, his love of food wouldn’t show until he was about 23 years old. During his undergraduate career, he majored in health studies and discovered a passion for nutrition, learning as much as he possibly could. Eventually, this led to cooking and baking more, as well as helping friends and family make healthier food choices. He began baking bread and cooking all the time, trying new recipes and even attempting to make his own. Now, he cooks nearly every day for him and his partner. He loves trying new things in the kitchen. Recently discovering a fondness for making hot sauce, one his favorite condiments. His favorite foods to make include bread, pasta, and anything spicy. He spent a couple years working as a barista and discovered a whole new world of coffee. He loves going to new coffee shops and making coffee at home. When he is not cooking, you can find him reading, watching movies, or playing board games with friends and family. His love of film is just as strong as his love of movies. His favorite film is Pan’s Labyrinth.

♦♦♦♦♦

Growing up primarily in a single-parent household, Lucas Quintero (he/him, they/them) would often help their mother prepare dinner for their family. This gave Lucas a foundational knowledge of foods and cooking. Coupled with some home-economics classes in middle school and frequent viewings of Disney Pixar’s Ratatouille, Lucas would only become more fascinated with the art and preparation of foods.

Growing up primarily in a single-parent household, Lucas Quintero (he/him, they/them) would often help their mother prepare dinner for their family. This gave Lucas a foundational knowledge of foods and cooking. Coupled with some home-economics classes in middle school and frequent viewings of Disney Pixar’s Ratatouille, Lucas would only become more fascinated with the art and preparation of foods.

Lucas currently resides in Boston and has been a MA native their whole life. They were raised on the South Shore of Massachusetts and received their B.A. in Psychology from Framingham State University.

After some ventures in various fields such as healthcare and non-profit work, Lucas eventually found himself as an Administrative Coordinator BU’s Residential Life Department in August of 2022. It was here that Lucas learned about BU’s Master’s Program in Gastronomy and (with the encouragement of their friends, family, and work colleagues) decided to apply.

With a master’s degree in Gastronomy, Lucas hopes to take what has always been a passive interest of mind and act upon it. They wish to adopt a career that grants them the ability to unite people in a meaningful (and fun!) way using food.

In their off time, you can typically find Lucas exploring nature trails, analyzing films and TV shows, or dancing their heart out wherever there is music playing. They love to appreciate the little pockets of sunshine that life has to offer, whether it be a beautiful sunset or a delicious cup of coffee in the morning. Lucas is a firm believer that there is always reason to make oneself smile. Lucas is beyond excited to expand their involvement at BU and cannot wait to see what this new experience will bring!

♦♦♦♦♦

Jessica Schumann was born and raised in Guatemala City, Guatemala. From a young age her goal was to be an entrepreneur like her parents. She moved to the USA to attend grad school. She holds an MBA from Suffolk University and a MS in Marketing from Boston University MET. She started a few small ventures throughout the years, but she didn’t find her true passion until two years ago. She started baking bread and desserts for friends and family while she stayed at home without being able to work. One year later her new food business was established when she joined Hope & Main, the first food business incubator in Rhode Island. The business, Mariela’s Sweets, is named after her 5-year-old daughter, and it is currently dedicated to creating beautiful French macarons.

Jessica Schumann was born and raised in Guatemala City, Guatemala. From a young age her goal was to be an entrepreneur like her parents. She moved to the USA to attend grad school. She holds an MBA from Suffolk University and a MS in Marketing from Boston University MET. She started a few small ventures throughout the years, but she didn’t find her true passion until two years ago. She started baking bread and desserts for friends and family while she stayed at home without being able to work. One year later her new food business was established when she joined Hope & Main, the first food business incubator in Rhode Island. The business, Mariela’s Sweets, is named after her 5-year-old daughter, and it is currently dedicated to creating beautiful French macarons.

The past year and a half Jessica has been part of many local markets that allowed her to connect to her customers and to grow her business. She is now in the process of building her own commercial kitchen to expand production capacity and product line.

Jessica has realized the roadblocks and challenges that many entrepreneurs face, particularly women owned business and Latin businesses. Her goal is to continue building her business and with her experience help her community. She wants to be part of the change that will open doors to underserved communities, like the Hispanic community.

Jessica is new to the food industry; she wants to dive in fully and being part of the Gastronomy program at BU is the perfect next step to accomplish her personal and business goals.

♦♦♦♦♦

Tiffany Taylor has been waiting for the gastronomy program to start an online master’s degree since she graduated with her communication bachelor's degree in 2016.

Tiffany Taylor has been waiting for the gastronomy program to start an online master’s degree since she graduated with her communication bachelor's degree in 2016.

Living right outside the big city of Fort Worth, she teaches all levels of culinary arts and food science at Rio Vista High School. Her goal is to give them an education that transcends their smaller boundaries. From winning grand champion at the Texas High School BBQ Cookers Association and through transforming their kitchen with the Rachael Ray foundation's Grow grant. After building a coffee shop, and growing their catering business, they are currently working on putting up a greenhouse and providing a quality lunchroom experience.

When not at work, she enjoys listening to her church's band and working on her 1950s farmhouse or traveling with her husband and their two teenage daughters. Upon graduation, she hopes to become a professor, help write culinary textbooks and curriculum.

♦♦♦♦♦

Bruce Arlen Wasserman began his relationship with food as a teenager when he took it upon himself cook all his own food, motivated by the whole food movement. Then, 20 years ago, he created a personally driven, hands-on course in cooking, challenged by his reading of a cookbook by British Chef Nigel Slater. For one year he cooked entirely from scratch until his relationship with the raw base that builds out recipes was more like a conversation. Later, he found and devoured books by chefs like Julia Child, Thomas Keller, Emeril Lagasse, John Besh, Emily Luchetti, Yotam Ottolenghi, Michel Roux and Tyler Florence. He and his wife have traveled to France, Italy, England, Scotland, Puerto Rico and Israel, finding local food ranging from street vendors and patisserie to a 3-star Michelin restaurant. He has cherished buying local ingredients and creating unique dishes with them in his travels. Bruce visited a chef’s supply in Paris and carefully packed his suitcase full with pans and assorted culinary tools and has collected cookbooks in French, Hebrew, Spanish and Italian.

Bruce Arlen Wasserman began his relationship with food as a teenager when he took it upon himself cook all his own food, motivated by the whole food movement. Then, 20 years ago, he created a personally driven, hands-on course in cooking, challenged by his reading of a cookbook by British Chef Nigel Slater. For one year he cooked entirely from scratch until his relationship with the raw base that builds out recipes was more like a conversation. Later, he found and devoured books by chefs like Julia Child, Thomas Keller, Emeril Lagasse, John Besh, Emily Luchetti, Yotam Ottolenghi, Michel Roux and Tyler Florence. He and his wife have traveled to France, Italy, England, Scotland, Puerto Rico and Israel, finding local food ranging from street vendors and patisserie to a 3-star Michelin restaurant. He has cherished buying local ingredients and creating unique dishes with them in his travels. Bruce visited a chef’s supply in Paris and carefully packed his suitcase full with pans and assorted culinary tools and has collected cookbooks in French, Hebrew, Spanish and Italian.

His interest in gastronomy reached a critical mass that brought him to the MA in Gastronomy degree program, which will allow him to take this pursuit to the next level. Bruce is excited to be a part of the program and looks forward to meeting his fellow students.

He has had a full career as a dentist, has an MFA in Writing and is a literary critic. His book, The Broken Night, was recently published by Finishing Line Press. Bruce is a potter and a musician and at one point, ranched in the vast spaces of northern Wyoming, where the aroma of wild sage on the breeze is something like a culinary garnish for everyday life.

Course Spotlight: Writing Cookbooks

Jessica Carbone (she/her/hers) will be teaching MET ML 610, Writing Cookbooks, in the spring 2023 semester.

Course Description:

Cookbooks are artful, researched, evocative, and often personal texts that take a tremendous amount of craft and vision to execute. They are also products that sit at the unusual intersection of literature and commerce, informing but also soliciting the buy-in of a broad, varied readership. How are cookbooks crafted, and what considerations should be taken to make a cookbook as powerful and successful as possible?

Here is a bit of Professor Carbone’s vision for the course:

This course is designed both for students who have long desired to write a cookbook, but also for people who wish to have a more critical, engaged conversation about the process of crafting and selling a cookbook into the broader culinary marketplace.

The class will toe that line between art and commerce, looking at examples of successful and pathbreaking cookbooks across culinary history (and across culinary audiences) and the opportunities to develop voice, argument, and aesthetic in the cookbook format, while also investigating such details of a successful proposal as recipe development and styling, researching comparable titles, and thinking about the potential sales and placement issues required for a cookbook to reach its target audience.

A typical class will involve a blend of workshopping materials for each student's cookbook proposal, a discussion of readings and assigned tasks, and guest lectures from experts in the cookbook field, including leading culinary book agents, trained recipe developers and testers, and experienced food photographers and stylists. (We may even take over the kitchen a few times to test—and taste--each other's recipes!) By the end of the semester, students will have a complete draft of a cookbook proposal (with recipes and photographs) in hand to develop and potentially pitch to future outlets.

Whether or not you intend to become a cookbook author someday, this class should deepen your understanding of the genre and the multifaceted work it entails.

MET ML 610 Writing Cookbooks will meet in-person Tuesdays 6:00-8:45 pm for the Spring 2023 semester.

The course is open to graduate students and upper-level undergraduates who may register via the Student Link. Non-degree seeking students can find registration information here.

Course Spotlight: Food & Art

Carmel Beer and Michal Evyatar will be co-teaching MET ML 672 Food and Art for the Spring 2023 semester.

Course Description:

Many rituals in diverse parts of the globe were created to gather people around food and eating. For example, the "Sagra" in Italy to celebrate the local seasonal yield, the Bougoule festival that celebrates the first vintage and the Jewish Passover Seder feast, to commemorate the people of Israel's journey in the desert. Food and Art is a course that explores the ingredients of food and eating "experiences'' and channels it through the five senses. In this class we will unpack personal and communal experiences through food and eating and their environments, thereby invoking both past and present. By creating immersive experiences, we aspire to deconstruct the mechanism of eating and to expose the patterns and norms involved. The course will culminate with a communal event, wherein the students will present their research outcomes and insights as installations.

The course will begin as Professor Beer and Professor Evyatar introduce the students to their own work with Mela studio where they create multi-sensory events with installations and performances that blend the culinary, performance, and visual arts.

Students will be taught to create art that is not only visible but able to touch all the senses. The five senses will be explored individually, with a few classes spent on each.

Here are a few examples of how the class will dive in:

- Sight- examine food represented in art, consider translation from a work of art to a dish, interpret paintings and translate that to something that can be consumed

- Touch- design eating tools that create a choreography with the body and the eater, consider how eating postures, textures, and temperatures impact experience

- Smell- make a smell diary as a part of a journey to focus more on this sense and develop a smell vocabulary

- Taste- view taste as a cultural detector and learn about cultures through their food with a specific focus on Israel

- Hearing- explore sound in performance pieces, hear music inspired by food, see how food varies when we hear different sounds

Class format will combine theoretical and hand-on learning as students participate, learn from each other, and get feedback in order to shape their own interpretations of the material.

The course will culminate in a public event where students will feature their own performance or installation that combines elements learned throughout the term.

There is no specific background required for the course although a fascination with food and art is recommended. Because it will be very art driven it will suit those who have a connection to visual or performance art. Students will learn to consider food as a symbol for culture, not focus on technique, restaurants, or specific dishes.

As Professor Beer put it, “The food we use exists in the art world.”

MET ML 672 Food and Art will meet in-person Tuesdays 6:00-8:45 pm for the Spring 2023 semester.

The course is open to graduate students and upper-level undergraduates who may register via the Student Link.

Non-degree seeking students can find registration information here.

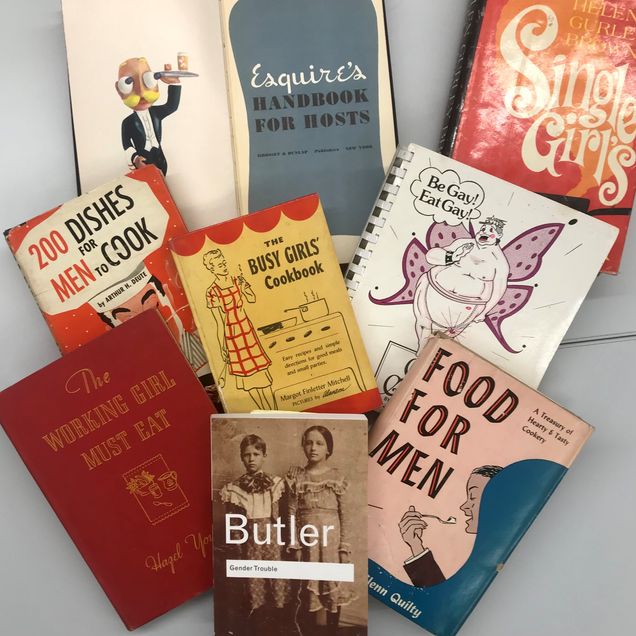

Course Spotlight: Food and Gender

Dr. Megan Elias will be teaching MET ML 706, Food and Gender, in the spring 2023 semester. Here is a preview of her plans for the class:

I am really excited to be teaching Food and Gender again after two years. It is my favorite class because every time I teach it I get to re-think some of our most basic assumptions about food and who we are. I see everything around me differently and students have told me that the same thing happens to them. We take an intersectional approach, so our conversations reach far into questions of identity and power.

Students assign half of our readings/viewings/activities and I have found myself watching Tamil sit coms, reading poetry about fermentation, and acting out an old family recipe, to name just a few of the student-designed assignments. We have wide ranging, challenging conversations in this class and the student projects always reflect that. I would say that of the classes I teach, it engages most with popular culture and media of the moment.

We will be reading some amazing classics, like Psyche Williams Forson’s Building Houses out of Chicken Legs, and some thrilling new work, like Diners, Dudes and Diets, by Gastronomy graduate Emily Contois, and Nurturing Masculinities, by Nefissa Naguib about food and masculinity in the Arab world. And, of course, at the end of the semester we’ll have one thought-provoking and probably also delicious thematic potluck to bring everything we have learned to the table and onto our plates.

MET ML 706, Food and Gender, will meet on Thursday evenings in the spring 2023 semester, starting on January 19. The course is open to graduate students and upper-level undergraduates. Non-degree seeking students can find registration information here.

Course Spotlight: Culinary Tourism

The Gastronomy program is thrilled to have Alicia Kennedy teaching MET ML 692 E1, Culinary Tourism for the Spring 2023 term.

This new 4-credit course is in hybrid format, combining online content with a week of in-person excursions and activities in Puerto Rico during BU’s spring break (March 5-11, 2023).

Course Description:

'Culinary Tourism', sometimes called 'Food Tourism' or 'Gastronomy Tourism' encompasses the active engagement with food and beverage experiences within a given culture or society, reflecting a sense of place, heritage, or tradition. Most often associated with international travel focusing on food, drink and tourist economies, examples of culinary tourism are increasingly found even domestically, in one's own home city or town. The idea of exploring a place for culinary purposes (eating, drinking, cooking, learning about local and regional foods) has a long history, however today the travel industry is showing record numbers with no signs of slowing. Nearly 50% of international travelers cite food and drink as the primary purpose of their journeys and the field has never offered so many options and of food and drink experiences to choose from.

From 'gourmet' chef-led tours and ultra-local street food crawls to home cooking classes, agricultural visits, and everything in between, this course will consider both the theoretical and practical aspects of culinary tourism in the 21st century. It will focus on questions around identity (food as expression), authenticity ('going to the source'), commoditization ('who gets to cook/eat what and why?') and the role of food and travel media, as well as travel industry issues such as over-tourism, environmental impact and cultural appropriation.

On top of learning the history and concepts behind culinary tourism's development, students will be taught a practical approach, looking at how the industry itself functions -- how are food and drink tours/experiences put together? Who are the industry stakeholders? What are the trends and forces driving the growing interest and what affect can this have -- both good and bad -- on local economies and cuisines?

In addition to hearing from guest speakers who are currently working in media, the class will have a workshop feel as students spend time reading, writing, and discussing work with one another. Featured here , the literature throughout the course will present a variety of valuable food studies perspectives intended to drive the conversation that the trip will then reinforce.

Students will be responsible for making and paying for their own travel and accommodation arrangements. The cost of excursions and activities are included in tuition - there is no additional fee for this course.

A course information meeting was held on 11/1/22, here you will find a link to the recording .

This class is web-reg restricted, meaning students cannot register for it via the Student Link.

If you would like to request registration please complete this form.

Please direct any further questions to Barbara Rotger (brotger@bu.edu)

Welcome new students for fall 2022, part 3

We are welcoming a bumper crop of new Gastronomy and Food Studies students for the fall semester. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Hailey DeLorey (She/Her/Hers) has always known that her passion was food. Whether it was cooking, baking, trying new restaurants, or enjoying the company of others around food, she always found the kitchen to be her happy place. Starting out as a home chef and moving into catering in college set her up to attend George Mason University where she graduated in May 2022 with a BS in Community Health specializing in Nutrition. While attending GMU, Hailey was able to explore the issues around food insecurity and how food interacts with one’s health and happiness from both a medical and cultural point of view. She hopes to further this interest at BU’s Gastronomy program by exploring more of the ways different food cultures influence people and bridge her degree in healthcare with a greater culinary knowledge.

Hailey DeLorey (She/Her/Hers) has always known that her passion was food. Whether it was cooking, baking, trying new restaurants, or enjoying the company of others around food, she always found the kitchen to be her happy place. Starting out as a home chef and moving into catering in college set her up to attend George Mason University where she graduated in May 2022 with a BS in Community Health specializing in Nutrition. While attending GMU, Hailey was able to explore the issues around food insecurity and how food interacts with one’s health and happiness from both a medical and cultural point of view. She hopes to further this interest at BU’s Gastronomy program by exploring more of the ways different food cultures influence people and bridge her degree in healthcare with a greater culinary knowledge.

Hailey currently works in food acquisition at the Greater Boston Food Bank. She recently moved to Boston where she lives with many, many roommates and is always looking for a new restaurant recommendation.

Naleen Camara (she/her) will never turn down a little treat.

In her youth, Naleen would spend summers growing tomatoes in her backyard with her father and taking trips to the wholesale warehouse to buy food in bulk for her family’s market. She’d sit knee to knee with her sisters and mother pounding, draining and mixing together ginger root to create the perfect, spicy drink for her mother’s friends at work. She’d even test out the different plants in her front yard to see which were edible (spoiler: none of them were.)

Outside of her interest in growing, making and eating food, Naleen is deeply interested in advocating for an individual’s right to a meal. After taking a food writing class during her last semester of undergrad, she began to investigate the question who gets to eat in America? The course challenged Naleen and her classmates to understand accessibility to something that should be an inherent right for everyone in the world. She also began learning about how food interacts with social constructs, analyzing how food culture intertwines with race, sex, gender, class and religion.

When Naleen doesn't have food on the mind, she’s typically listening to a podcast, going on a walk or painting.

A Wisconsin native with a B.S. in Horticulture from the University of Nebraska- Lincoln, Christine Barta now resides in central Texas with her partner, Frank, and their 13-year-old Maltese, Oscar. She is currently the Market Garden & Retail Manager at World Hunger Relief, Inc in Waco, TX.

A Wisconsin native with a B.S. in Horticulture from the University of Nebraska- Lincoln, Christine Barta now resides in central Texas with her partner, Frank, and their 13-year-old Maltese, Oscar. She is currently the Market Garden & Retail Manager at World Hunger Relief, Inc in Waco, TX.

Having grown up in the Midwest, Christine learned pretty early on that sitting around the table was one of her favorite pastimes. The conversation never dwindled until the spread did, and even then, Midwestern goodbyes take about 200% longer than anywhere else. Gardening with her mom, hunting and fishing with her dad, and going out to eat with her sister (and sister’s friends) taught Christine a lot about what makes a good meal: the company.

While her interest specifically in Gastronomy is a bit newer, Christine can often be found reading food literature (she is currently on a Ruth Reichl kick), playing laid-back video games, or spending time with her friends and partner. She hopes that this program will allow her to not only expand her palate and knowledge, but to also become more aware on the sociocultural impact of food globally.

Sharmila Bhide is a foodtech entrepreneur; An experimental cook; An amateur food scientist; A Michelin star frequenter; a hole-in-the-waller.

Sharmila Bhide is a foodtech entrepreneur; An experimental cook; An amateur food scientist; A Michelin star frequenter; a hole-in-the-waller.

This is how she introduces herself on her Instagram handle aptly named glutonix.

She is a CPA and an MBA from Yale and has spent the last 25 years working with numbers and finances and business. While the head was busy doing number crunching, the heart was always immersed in all aspects of food - cooking, eating, reviewing and researching.

She decided to marry her love for food and training in business to launch a successful foodtech startup. However when COVID hit, it slowed down the business and he started exploring studying in food. She has done an online course at Harvard on Science of cooking and enjoyed the class so much that she decided to go back to school to learn and research all aspects of food - history, science, anthropology, evolution etc.

She is extremely excited to begin her course at BU and be immersed fully into anything and everything about food😀

Cooking and food has been an important part of Michael Fleming’s life from an early age. Being raised in a large family in Staten Island, NY, cooking for the masses was a weekly adventure. He has vivid memories of plating antipasto with one grandmother and watching Julia Child with another. His fondest moments growing up revolved around the table. During high school, Michael started preparing meals for family and friends and experimenting with new foods and flavors. During college, Michael realized his other passion. While working on his Associates Degree in Culinary Arts, Michael started working with children during an after school program. He transferred to Georgian Court University where he earned a Bachelor’s in Humanities with a dual certification in Elementary and Special Education. He continued and received his Master’s in Educational Leadership. For the past ten years Michael has been teaching special education at Aldrich School in Howell, New Jersey. He has maintained a plethora of food related part time jobs including working at a spice shop, a key holder at Sur La Table, a brunch chef at a boutique hotel, and a caterer.

Cooking and food has been an important part of Michael Fleming’s life from an early age. Being raised in a large family in Staten Island, NY, cooking for the masses was a weekly adventure. He has vivid memories of plating antipasto with one grandmother and watching Julia Child with another. His fondest moments growing up revolved around the table. During high school, Michael started preparing meals for family and friends and experimenting with new foods and flavors. During college, Michael realized his other passion. While working on his Associates Degree in Culinary Arts, Michael started working with children during an after school program. He transferred to Georgian Court University where he earned a Bachelor’s in Humanities with a dual certification in Elementary and Special Education. He continued and received his Master’s in Educational Leadership. For the past ten years Michael has been teaching special education at Aldrich School in Howell, New Jersey. He has maintained a plethora of food related part time jobs including working at a spice shop, a key holder at Sur La Table, a brunch chef at a boutique hotel, and a caterer.

An avid traveler, Michael enjoys experiencing the world through cuisine. Having visited over 30 countries, Michael has taken a cooking class or food tour in nearly all of them. He finds pleasure in bringing new ingredients, techniques, and recipes home and trying them out on family and friends. During the pandemic, Michael became really interested in cooking, recipe development, and food history. He scoured cookbooks and prepared a new recipe nightly for his two roommates, teaching both how to cook (and wash the dishes!) Currently, Michael is beginning his eleventh year teaching language and learning disabled students and working part time for a cinema start-up called Cinema Lab at his local cinema. Michael resides in Bradley Beach, New Jersey.

Born and raised in Atlanta, GA, Amy Phuong grew up watching Yan Can Cook on PBS while doing her homework as her parents worked late. She developed a love of food getting homecooked meals every day from her mom and going grocery shopping as a typical weekend activity. Her first memory of when she realized her food was culturally different was one day, in grade school, Amy came home to ask her mom to get a McDonald’s hamburger like all the other kids. On modest means, her mom told Amy she would send her a homecooked hamburger as her school lunch that week. Amy was excited about getting a hamburger for lunch – only to find a cold, fried pork chop sandwiched between two slices of white bread as her ‘hamburger’. She didn’t have the heart to explain to her mom that wasn’t what she wanted.

Born and raised in Atlanta, GA, Amy Phuong grew up watching Yan Can Cook on PBS while doing her homework as her parents worked late. She developed a love of food getting homecooked meals every day from her mom and going grocery shopping as a typical weekend activity. Her first memory of when she realized her food was culturally different was one day, in grade school, Amy came home to ask her mom to get a McDonald’s hamburger like all the other kids. On modest means, her mom told Amy she would send her a homecooked hamburger as her school lunch that week. Amy was excited about getting a hamburger for lunch – only to find a cold, fried pork chop sandwiched between two slices of white bread as her ‘hamburger’. She didn’t have the heart to explain to her mom that wasn’t what she wanted.

From Geologist to Full-time Mom to Personal Chef, Jessica Wilson is an avid believer in the mantra “Never Stop Learning”. She loved her 14 years as a Geologist in the Energy Industry where she was able to work collaboratively with multi-functional teams both domestically and internationally in addressing challenging, time-sensitive scientific and operational problems, as well as personal topics with fellow geologists via management and staffing and development. However, while there, she began to realize just how many people, often with dual career families, work hard every day only to come home in the evening exhausted and unable to find the time to cook. Jessica truly believes in the health and wellness benefits that a good, clean, home-cooked meal provides, and that, coupled with her frustration at not being able to indulge in her passion for cooking as much as she would have liked, led her to make the decision to pivot onto a new culinary path. After earning a Diploma in Culinary Arts, she worked as a personal chef, serving seniors in her community. She is also a certified Culinary Coach via the CHEF (Culinary Health Education Fundamentals) training program offered by the Institute of Lifestyle Medicine. Throughout her life, Jessica has been grateful for her ability to enjoy a deep-rooted connection to the land as she continues to work with her father and their farmer-business partners to continue their 100+ year family legacy of farming corn and soybeans in Cumberland County Illinois. Jessica currently lives in Texas and misses the East Coast. For fun, she enjoys reading, cooking, practicing food photography, teaching her sons to cook and eating the cupcakes her son Patrick loves to make. She is also always up for a glass of cabernet sauvignon and dark chocolate.

From Geologist to Full-time Mom to Personal Chef, Jessica Wilson is an avid believer in the mantra “Never Stop Learning”. She loved her 14 years as a Geologist in the Energy Industry where she was able to work collaboratively with multi-functional teams both domestically and internationally in addressing challenging, time-sensitive scientific and operational problems, as well as personal topics with fellow geologists via management and staffing and development. However, while there, she began to realize just how many people, often with dual career families, work hard every day only to come home in the evening exhausted and unable to find the time to cook. Jessica truly believes in the health and wellness benefits that a good, clean, home-cooked meal provides, and that, coupled with her frustration at not being able to indulge in her passion for cooking as much as she would have liked, led her to make the decision to pivot onto a new culinary path. After earning a Diploma in Culinary Arts, she worked as a personal chef, serving seniors in her community. She is also a certified Culinary Coach via the CHEF (Culinary Health Education Fundamentals) training program offered by the Institute of Lifestyle Medicine. Throughout her life, Jessica has been grateful for her ability to enjoy a deep-rooted connection to the land as she continues to work with her father and their farmer-business partners to continue their 100+ year family legacy of farming corn and soybeans in Cumberland County Illinois. Jessica currently lives in Texas and misses the East Coast. For fun, she enjoys reading, cooking, practicing food photography, teaching her sons to cook and eating the cupcakes her son Patrick loves to make. She is also always up for a glass of cabernet sauvignon and dark chocolate.

Fall 2022 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy

Fall 2022 lectures will be presented both in-person and via webinar format. Registration is free and open to the public – please follow the link for each program to register.

SEPTEMBER

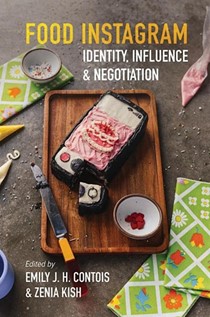

Food Instagram: Identity, Influence, and Negotiation

with Emily Contois, KC Hysmith, and Zenia Kish

Zoom Webinar: participants will be sent link one day prior to the lecture.

Image by image and hashtag by hashtag, Instagram has redefined the ways we relate to food. Emily J. H. Contois and Zenia Kish edit contributions that explore the massively popular social media platform as a space for self-identification, influence, transformation, and resistance. Artists and journalists join a wide range of scholars to look at food’s connection to Instagram from vantage points as diverse as Hong Kong’s camera-centric foodie culture, the platform’s long history with feminist eateries, and the photography of Australia’s livestock producers. What emerges is a portrait of an arena where people do more than build identities and influence. Users negotiate cultural, social, and economic practices in a place that, for all its democratic potential, reinforces entrenched dynamics of power.

Interdisciplinary in approach and transnational in scope, Food Instagram offers general readers and experts alike new perspectives on an important social media space and its impact on a fundamental area of our lives.

Emily J.H. Contois is Assistant Professor of Media Studies, University of Tulsa

KC Hysmith is a PhD Candidate in American Studies at the University of North Carolina

Zenia Kish is Assistant Professor Media Studies, University of Tulsa

*Save 30% on Food Instagram by ordering from University of Illinois Press with code S22UIP

Fri, September 23, 2022

12:00 PM – 1:00 PM EDT

OCTOBER

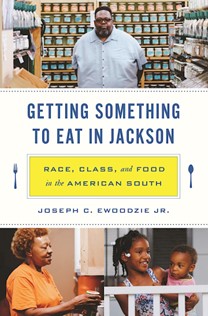

Getting Something to Eat in Jackson

with Joseph C. Ewoodzie Jr.

In person plus Zoom webinar: webinar participants will be sent link one day prior to the lecture.

Getting Something to Eat in Jackson uses food—what people eat and how—to explore the interaction of race and class in the lives of African Americans in the contemporary urban South. Joseph Ewoodzie Jr. examines how “foodways”—food availability, choice, and consumption—vary greatly between classes of African Americans in Jackson, Mississippi, and how this reflects and shapes their very different experiences of a shared racial identity.

Ewoodzie spent more than a year following a group of socioeconomically diverse African Americans—from upper-middle-class patrons of the city’s fine-dining restaurants to men experiencing homelessness who must organize their days around the schedules of soup kitchens. Ewoodzie goes food shopping, cooks, and eats with a young mother living in poverty and a grandmother working two jobs. He works in a Black-owned BBQ restaurant, and he meets a man who decides to become a vegan for health reasons but who must drive across town to get tofu and quinoa. Ewoodzie also learns about how soul food is changing and why it is no longer a staple survival food. Throughout, he shows how food choices influence, and are influenced by, the racial and class identities of Black Jacksonians.

By tracing these contemporary African American foodways, Getting Something to Eat in Jackson offers new insights into the lives of Black Southerners and helps challenge the persistent homogenization of blackness in American life.

Joseph C. Ewoodzie Jr. is associate professor of sociology at Davidson College. He is the author of Break Beats in the Bronx: Rediscovering Hip-Hop’s Early Years. He lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. Twitter @piko_e

Thu, October 13, 2022

6:00 PM – 7:00 PM EDT

Location:

Boston University College of Arts and Science, Room 211

685 - 725 Commonwealth Avenue

Boston, MA 02215

____________________________

Feeding Fascism: The Politics of Women's Food Work

with Diana Garvin

In person plus Zoom webinar: webinar participants will be sent link one day prior to the lecture.

Feeding Fascism explores how women negotiated the politics of Italy’s Fascist regime in their daily lives and how they fed their families through agricultural and industrial labor. The book looks at women’s experiences of Fascism by examining the material world in which they lived in relation to their thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Over the past decade, Diana Garvin has conducted extensive research in Italian museums, libraries, and archives. Feeding Fascism includes illustrations of rare cookbooks, kitchen utensils, cafeteria plans, and culinary propaganda to connect women’s political beliefs with the places that they lived and worked and the objects that they owned and borrowed. Garvin draws on first-hand accounts, such as diaries, work songs, and drawings, that demonstrate how women and the Fascist state vied for control over national diet across many manifestations – cooking, feeding, and eating – to assert and negotiate their authority. Revealing the national stakes of daily choices, and the fine line between resistance and consent, Feeding Fascism attests to the power of food.

Diana Garvin is Assistant Professor of Italian with a focus on Mediterranean Studies at the University of Oregon.

Wed, October 26, 2022

6:00 PM – 7:00 PM EDT

Location:

Groce Pépin Culinary Innovation Laboratory

808 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 124

Boston, MA 02215

NOVEMBER

Food in Memory and Imagination: Space, Place, and Taste

with Beth Forrest and Greg de St. Maurice

In person plus Zoom webinar: webinar participants will be sent link one day prior to the lecture.

Editors Beth M. Forrest, Professor of Liberal Arts at the Culinary Institute of America, and Greg de St. Maurice, Assistant Professor at Keio University, Japan will discuss the recently published volume Food in Memory and Imagination: Space, Place and, Taste.

How do we engage with food through memory and imagination? This expansive volume spans time and space to illustrate how, through food, people have engaged with the past, the future, and their alternative presents.

Beth M. Forrest and Greg de St. Maurice have brought together first-class contributions, from both established and up-and-coming scholars, to consider how imagination and memory intertwine and sometimes diverge. Chapters draw on cases around the world-including Iran, Italy, Japan, Kenya, and the US-and include topics such as national identity, food insecurity, and the phenomenon of knowledge. Contributions represent a range of disciplines, including anthropology, history, philosophy, psychology, and sociology. This volume is a veritable feast for the contemporary food studies scholar.

Fri, November 18, 2022

12:00 PM – 1:00 PM EST

Location:

Groce Pépin Culinary Innovation Laboratory

Boston University Gastronomy Program

808 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 124

Boston, MA 02215

We thank the Jacques Pépin Foundation for sponsorship of this lecture series.

Welcome new students for fall 2022, part 2

We are welcoming a bumper crop of new Gastronomy and Food Studies students for the fall semester. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Tracey Torres (she/her) grew up with a great appreciation for food. She was born and raised in the south suburbs of Chicago. As a child of Filipino immigrants, she was lucky to grow up eating home-cooked dishes almost every night. As years went on, a new dish would be added to the table like pasta with fresh tomatoes and basil after a neighbor brought it to a family party. The basil then would find itself in a Thai-inspired stir fry because her mom wanted to replicate their favorite takeout place. Tracey would continue to learn about food through dinner time with her family and by watching numerous episodes of Two Fat Lady’s, Yan Can Cook and of course, Jacques & Julia: Cooking at Home on PBS. Her interest in food followed her to the University of Iowa. However, she found herself spending more time in the public library reading cookbooks instead of attending class. She then transferred to Kendall College and graduated with a B.A. in Culinary Arts. During her undergrad, Tracey worked in many areas of the food world. She spent summers working at the farmers’ market, catered some wild gigs, and flipped burgers on the lake at a yacht club. However, the path she would take after graduation was cooking in Michelin-starred restaurants in Chicago and New York City.

Tracey Torres (she/her) grew up with a great appreciation for food. She was born and raised in the south suburbs of Chicago. As a child of Filipino immigrants, she was lucky to grow up eating home-cooked dishes almost every night. As years went on, a new dish would be added to the table like pasta with fresh tomatoes and basil after a neighbor brought it to a family party. The basil then would find itself in a Thai-inspired stir fry because her mom wanted to replicate their favorite takeout place. Tracey would continue to learn about food through dinner time with her family and by watching numerous episodes of Two Fat Lady’s, Yan Can Cook and of course, Jacques & Julia: Cooking at Home on PBS. Her interest in food followed her to the University of Iowa. However, she found herself spending more time in the public library reading cookbooks instead of attending class. She then transferred to Kendall College and graduated with a B.A. in Culinary Arts. During her undergrad, Tracey worked in many areas of the food world. She spent summers working at the farmers’ market, catered some wild gigs, and flipped burgers on the lake at a yacht club. However, the path she would take after graduation was cooking in Michelin-starred restaurants in Chicago and New York City.

After spending 12 years in professional kitchens, Tracey decided to pivot to the corporate world after having her son. Restaurant life with a young child was as hard as it may seem. She is currently working as a Culinary Specialist at a large CPG company, enjoying the product innovation process while also sneaking in some recipe development. She is so excited to join the BU Gastronomy community and continue learning and growing in the Culinary world.

Alison Barricklow ’s primary love language has always been food. She learned to love cooking, baking, and the joy of sharing a meal with others when she was a child, and her passion ultimately led her to a career in the hospitality industry. She began working in restaurant kitchens when she was a teenager, and moved on to roles in catering, meeting and event management, and food and wine travel as her career progressed. Her most recent position was as a Tour and Travel Director for an international wine distributor where she planned and managed small group food and wine tours in Europe.

Alison Barricklow ’s primary love language has always been food. She learned to love cooking, baking, and the joy of sharing a meal with others when she was a child, and her passion ultimately led her to a career in the hospitality industry. She began working in restaurant kitchens when she was a teenager, and moved on to roles in catering, meeting and event management, and food and wine travel as her career progressed. Her most recent position was as a Tour and Travel Director for an international wine distributor where she planned and managed small group food and wine tours in Europe.

Alison attended Wheaton College in Norton, MA in the mid 80’s, but had to leave before graduating. She was finally able to take a career break in 2019 to complete her degree and graduated Southern New Hampshire University in March 2020, just as the pandemic lockdown began. Unfortunately, she has been unable to move forward in her career since then, which is why she decided on the Gastronomy program. She has ideas for a culinary travel business but wants to stay open for now to see where this experience could potentially lead her.

When Alison and her husband became empty nesters, they relocated to Los Angeles from New Hampshire, so she is participating as an online student. She loves the California weather most of the year, but misses fall in New England, especially when it comes to apple picking, fresh apple cider, and hot apple cider donuts! She hopes to attend class in person one fall term so she can satisfy her food cravings.

In her free time, Alison loves to travel, explore food markets, go wine tasting, take food tours, visit museums, hike, read, take way too many photos, and spend time with her husband and children.

Isabella Pedroli Giordano was born and raised in Los Angeles, California and spent fifteen years cooking professionally. A self-proclaimed Italophile, she honed her craft in Italian kitchens in California, the Republic of San Marino, and Italy. She apprenticed in San Marino, Le Marche and Emilia-Romagna during various points of her career. A perpetual student, she returned to community college in 2017, eventually transferring to the University of California, Davis. There, she majored in Spanish and minored in Italian. Ultimately, her goal is to bridge her culinary knowledge with literature and language, to comprehend the nuances of the origin and history of food. In understanding how and why food or a dish are part of a specific culture, Isabella hopes to better communicate and tell stories about a given culture. She also believes that good food should be accessible to all, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Through the pursuit of formal education, Isabella would like to reach a broader audience in her future career. She envisions teaching at the community college level or in a community-based setting, working towards making wholesome and home-cooked food accessible and manageable for underserved communities. She would like to use her knowledge of Spanish to reach Spanish-speaking communities and people of color.

Isabella Pedroli Giordano was born and raised in Los Angeles, California and spent fifteen years cooking professionally. A self-proclaimed Italophile, she honed her craft in Italian kitchens in California, the Republic of San Marino, and Italy. She apprenticed in San Marino, Le Marche and Emilia-Romagna during various points of her career. A perpetual student, she returned to community college in 2017, eventually transferring to the University of California, Davis. There, she majored in Spanish and minored in Italian. Ultimately, her goal is to bridge her culinary knowledge with literature and language, to comprehend the nuances of the origin and history of food. In understanding how and why food or a dish are part of a specific culture, Isabella hopes to better communicate and tell stories about a given culture. She also believes that good food should be accessible to all, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Through the pursuit of formal education, Isabella would like to reach a broader audience in her future career. She envisions teaching at the community college level or in a community-based setting, working towards making wholesome and home-cooked food accessible and manageable for underserved communities. She would like to use her knowledge of Spanish to reach Spanish-speaking communities and people of color.

Isabella currently resides in Urbana, Illinois with her partner, Brian, who is a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Isabel Marie Barbosa, whose pronouns are she/they, has always recognized food as a connective component of the human experience. Growing up in Southern California, they regularly threw elaborate dinner parties, cooking for and with friends, and were known to show up to school with sweets to share. Over the years, they have observed the way food, and our relation to it, has been a tool to connect with, or distance ourselves from, community.