Course Spotlight: Archaeology of Food

Our summer term course, MET ML 611, Archaeology of Food, with Dr. Karen Metheny, introduces students to the archaeological study of food and foodways in prehistoric and historic-period cultures, with a specific focus on how food was obtained, processed, consumed, and preserved in past times, and the impact of diet upon past human populations in terms of disease and mortality. Students will learn how archaeologists use a wide range of artifacts, plant remains, human skeletal evidence, animal remains, and other data to recover information about food use and food technology over time to reconstruct past foodways practices. This introduction will be followed by a survey of the archaeological evidence of foodways from the earliest modern humans to the first farmers to more recent historical periods. Key topics will include the domestication of plants and animals, feasting, the role of households in food production, and the archaeological evidence for gender and status in cooking, preparation areas, serving vessels, and consumption. The course highlights specific foodstuffs, staples, and beverages, such as cacao and chocolate, maize, wheat, barley, beer, wine, sugar, and tea in order to show not only the range of evidence that can be brought to bear, but also how the reconstruction of foodways can reveal critical information about past cultural practice, social structure, identities, and meaning across time and space.

We will hear from experts on the origin of beer and bread, and then debate the question of which came first. Students will select a specific food or beverage to study during the semester and will engage in weekly projects to investigate how that food or beverage was prepared and served during a daily meal or in ritual context, what tools and cooking techniques were used, what ingredients were needed, who would have prepared and/or consumed this food, and its social and cultural significance. Finally, students will research and prepare a food or duplicate a food technology.

MET ML 611, Archaeology of Food meets on Tuesday and Thursday evenings from 5:30 to 9 pm, EST, from May 25 to July 1, 2021.

This class will be offered in fully remote format. Non-degree seeking students will find registration instructions here.

Offally Nice:

Reducing Meat Waste by Learning to Love Organs and Accepting Other Cultures

Students in MET ML 626, Food Waste: Scope, Scale, & Signals for Sustainable Change, are contributing posts this month. Today's is from Gastronomy student Samantha Maxwell.

The often-cited Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3 aims to reduce global food waste by 50 percent by 2030. However, according to all metrics, the world is woefully behind schedule when it comes to meeting this goal.

Perhaps the most egregious of our food waste sins is the wasting of meat products. That’s because when we waste meat, we’re not just wasting the flesh of the animal itself—we’re also wasting the huge number of resources that went into raising and housing that animal and preparing it for slaughter. If we feel guilty about throwing out that shriveled cucumber in the back of our fridge, we should be concerned about pitching out that half-eaten package of ground turkey even more.

But some meat waste happens not because we forget to cook the pork that gets lost in the back of our fridge. Instead, it happens before the food even reaches our homes. Particularly in the U.S., offal meats, organs including tripe, liver, and kidney, are unpopular cuts of meat. Instead, we’d rather opt for the chicken breast and legs instead of the liver. Wondering what happens to those organ meats? They often go to waste completely, since grocery stores know that there is limited demand for them. In fact, can you remember the last time you saw kidneys sold at your local chain supermarket?

Our disdain of organ meats is largely cultural, though. During WWII, when rationing was viewed as an important part of the war effort, organ meats were mainstream and considered enjoyable. A cookbook from this era entitled What Do We Eat Now? provides several offal recipes that are framed as neither exotic or undesirable: They were just normal cuts of meat. But as Americans got wealthier and had more access to more “desirable” cuts of meat, offal fell out of fashion. That’s a shame considering the nutritional content of many types of offal. Liver, for example, is an excellent source of iron, a mineral that many are deficient in.

Other cultures, though, continue to embrace offal and even treat it as a delicacy. The French make pate, which is considered a luxury food item by many. Many in east Asian countries eat tendon, which has a lovely soft, chewy texture when cooked in broth or marinated with flavorful fats. And in places like Spain and Panama, pig’s ears and trotters are considered a delicious appetizer, full of flavor and interesting textures.

The younger generations alive today are crossing cultural barriers like none before them. It’s easier than ever to connect with people on opposite sides of the world, and the relatively low prices of plane travel these days make international travel an option to more and more people across the world. As people in the United States and the rest of the non-offal-eating world gain greater access to parts of the planet where people do eat offal, we should start to question our own food habits. Why wouldn’t we adopt the practice of eating offal, especially when other cultures make it taste so good? International food is gaining more widespread acceptance in the U.S., which makes this a prime time for chefs and food influencers to make a push to make offal delicious again.

According to a 2019 study from Germany, choosing offal instead of more “conventional” meat just one or two times a week could “reduce livestock emissions by as much as 14 percent.” This sort of change doesn’t require people to give anything up to make a change—instead, it simply encourages them to try something new. And since people don’t like to feel like they’re being restricted, the idea of adding something into their diet is likely to seem more appealing than taking something out.

Of course, while reaching the goal of reducing food waste by 50 percent by 2030 is going to require a lot of changes to policy, we must also encourage individuals to change their habits. This doesn’t always have to be an unpleasant experience. When we can get eaters to expand their culinary horizons by eating offal, we’re not just reducing food waste—we’re also encouraging more cultural acceptance between different ethnic groups and nationalities. If we can do both at the same time and make it delicious in the process, why wouldn’t we?

Accelerating Food Waste Reduction

Boston University Metropolitan College (MET) and the Gastronomy and Food Studies Program invite you to a special event, Accelerating Food Waste Reduction.

It is hard to believe that in our modern and increasingly connected world, billions of pounds of food are lost or wasted annually, depriving needed nutrition to hundreds of millions of global citizens while accelerating pollution, biodiversity loss and climate change.

At the same time, Covid-19 has exposed the fragility of the global food system, initially leading to an increase in food loss and waste, while the linkage between food waste, biodiversity loss, and the potential for pandemics clearly signals the need to change our wasteful ways and create a regenerative food system.

The prior decade saw the emergence of a global food waste movement with considerable emphasis on awareness-raising, education, and budding innovation efforts, and while we entered the current decade with emphasis on moving from awareness to action at scale, we have much work to do to achieve broad-based transformational change. The pressing question remains:

How can we ignite efforts to truly make this a pivotal decade of action for global food waste reduction?

Join us on April 13th:

Join our webinar for a discussion with a panel of global experts as we build on the food waste reduction successes of the past decade with a “go-forward” view toward accelerating progress in the current “decade of action” anchored by a goal of halving global food waste by 2030. In this conversational session we will review progress on food waste reduction to date, assess key successes, initiatives, and linkages to leverage now, identify remaining barriers to change, and focus on how to advance food waste reduction in a more transformational manner within a more systemic frame.

Please register for the webinar here.

Panelists

Tristram Stuart is an international award-winning author, speaker, campaigner and expert on the environmental and social impacts of food . His books have been described as "a genuinely revelatory contribution to the history of human ideas” (The Times) and his TED talk has been watched over a million times. The environmental campaigning organisation he founded, Feedback, has spread its work into dozens of countries worldwide. He is also the founder of Toast Ale, which upcycles millions of slices of unsold bread into award-winning craft beer and donates its profits to charity.

Tristram Stuart is an international award-winning author, speaker, campaigner and expert on the environmental and social impacts of food . His books have been described as "a genuinely revelatory contribution to the history of human ideas” (The Times) and his TED talk has been watched over a million times. The environmental campaigning organisation he founded, Feedback, has spread its work into dozens of countries worldwide. He is also the founder of Toast Ale, which upcycles millions of slices of unsold bread into award-winning craft beer and donates its profits to charity.

Dana Gunders serves as ReFED’s Executive Director. Dana is a national expert on food waste and one of the first to bring to light just how much food is lost throughout the food system. For almost a decade, she was a Senior Scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). She then launched Next Course, LLC to strategically advise on the topic. Some of her career highlights include authoring the landmark Wasted report and Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook, launching the Save the Food campaign with the Ad Council, testifying in Congress, consulting to Google, appearing on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, and being a founding Board Member of ReFED.

Dana Gunders serves as ReFED’s Executive Director. Dana is a national expert on food waste and one of the first to bring to light just how much food is lost throughout the food system. For almost a decade, she was a Senior Scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). She then launched Next Course, LLC to strategically advise on the topic. Some of her career highlights include authoring the landmark Wasted report and Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook, launching the Save the Food campaign with the Ad Council, testifying in Congress, consulting to Google, appearing on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, and being a founding Board Member of ReFED.

Jonathan Deutsch, Ph.D., CHE, CRC is Professor in the Department of Food and Hospitality Management in the College of Nursing and Health Professions at Drexel University and Director of the Drexel Food Lab. He is the President of the Upcycled Food Foundation and previously was the inaugural James Beard Foundation Impact Fellow, leading a national curriculum effort on food waste reduction for chefs and culinary educators. He directs the Drexel Food Lab, a culinary innovation and food product research and development lab focused on solving real world food system problems in the areas of sustainability, health promotion, and inclusive dining. He is the author or editor of eight books including Barbecue: A Global History (with Megan Elias), and Gastropolis: Food and Culture in New York City (with Annie Hauck-Lawson) and numerous articles in journals of food studies, public health and hospitality education.

Jonathan Deutsch, Ph.D., CHE, CRC is Professor in the Department of Food and Hospitality Management in the College of Nursing and Health Professions at Drexel University and Director of the Drexel Food Lab. He is the President of the Upcycled Food Foundation and previously was the inaugural James Beard Foundation Impact Fellow, leading a national curriculum effort on food waste reduction for chefs and culinary educators. He directs the Drexel Food Lab, a culinary innovation and food product research and development lab focused on solving real world food system problems in the areas of sustainability, health promotion, and inclusive dining. He is the author or editor of eight books including Barbecue: A Global History (with Megan Elias), and Gastropolis: Food and Culture in New York City (with Annie Hauck-Lawson) and numerous articles in journals of food studies, public health and hospitality education.

Andrew Shakman is a food waste prevention advocate and the CEO of Leanpath, a technology solutions provider for the foodservice industry based in Portland, Oregon. In 2004, Leanpath invented the world’s first automated food waste tracking technology and today provides a complete food waste prevention platform including data collection hardware tools, cloud-based waste analytics and behavior change coaching. Leanpath technology is installed in more than 40 countries with clients including Sodexo, Google, and Aramark. Since 2014 alone, Leanpath has empowered culinary teams to prevent more than 63 million pounds of food from being wasted. Andrew is a member of ReFED’s Advisory Council and serves on the Board of Directors for Every Woman Treaty.

Andrew Shakman is a food waste prevention advocate and the CEO of Leanpath, a technology solutions provider for the foodservice industry based in Portland, Oregon. In 2004, Leanpath invented the world’s first automated food waste tracking technology and today provides a complete food waste prevention platform including data collection hardware tools, cloud-based waste analytics and behavior change coaching. Leanpath technology is installed in more than 40 countries with clients including Sodexo, Google, and Aramark. Since 2014 alone, Leanpath has empowered culinary teams to prevent more than 63 million pounds of food from being wasted. Andrew is a member of ReFED’s Advisory Council and serves on the Board of Directors for Every Woman Treaty.

The Fish-Case Fiasco: A Food Waste Story

Students in MET ML 626, Food Waste: Scope, Scale, & Signals for Sustainable Change, are contributing posts this month. Today's is from Gastronomy student Sabina Michelle Säfsten Routon.

It was an issue of convenience. Or, rather, one of inconvenience — wrapping that much fish just to store it for “some guy” to come pick it up later would cost 20 minutes of employee time twice a week, and that just didn’t make sense for the department. “Those minutes add up,” explained the Meat & Seafood manager, annoyed. I obviously didn’t understand the importance of the bottom line.

So, I watched them throw it away. It was “only” about $400-worth of fish, retail — $300 on a good winter sales week, $250 in the summer. In the trash bin, every Tuesday and Thursday evening at 9. No discounted food sales allowed to store patrons — and donating it, as previously explained, “didn’t make sense.”

I’m not sure how much fish mongers made per hour in Utah in 2013, but it must have been a pretty penny if 40 minutes of time wasn’t worth an $800-per-week tax write-off, or even a few hundred dollars in discounted sales. After briefly considering a career change, I instead decided to persuade them to change this wasteful behavior.

To be clear, I don’t even like fish. The only seafood I like is salmon (likely on account of being allergic to much of the rest of it). I was taking care of my mother at the time and receiving help from the community to pay for most of the grocery bill, so I certainly couldn’t afford to buy the fish. My self-righteous indignation was growing steadily, fueled by passive-aggressive jabs about wasted food.

Then, one day in April, it was too much to handle. We ended Thursday with over ten pounds of fresh halibut fillet. Caught on Tuesday, delivered Wednesday morning. The next shipment of fish was due to arrive Friday morning, so this leftover halibut was destined for the trash. Something inside me couldn’t handle that — so I bargained.

“What if I wrap it up for you? Will you not throw it away?” I asked Jonathan*, the fishmonger. He laughed. “And what am I going to do with ten pounds of halibut fillet? I don’t even like halibut!” he responded. “Well,” I said, feeling bold, “what would it take?”

After a few minutes of haggling, he presented his final offer: If I wrapped the fish, cleaned the fish case (off-the-clock), and bought everything left in the case, I could have the fish for 90% off. I immediately agreed.

“Wait, what are YOU going to do with ten-plus pounds of halibut fillet??” he asked, incredulously. I told him not to worry about it. When the time came, I clocked out, put on a mask and gloves (I’m allergic to the shellfish), and scrubbed the fish case. I figured a job well-done could lead to future bargains, so I went all-out. Thirty minutes later, I wrapped up my fish and took $267 worth of halibut home, instead of the groceries I’d planned.

Mom was more than a bit surprised, but was enthusiastic when I explained what had happened. Turns out my mom loved fish, and so did many of her family in the area. We had some very happy friends that weekend, and Mom was thrilled to be able to help them out. I explained to Mom that I wanted to make this a regular thing, and we crunched some numbers. There was no way we could afford it. I hit on another idea: if we were careful with accounts and numbers, we could buy the fish and then sell what we didn’t need to select friends and neighbors at 50–75% off. That way they still got a bargain, and we got our fish for free.

I started calling around to some trusted friends and we made our network. The next time Jonathan didn’t want to clean the fish case, I was ready. It soon became a pretty regular thing. While I didn’t love fish, I was in culinary school and was able to arrange to take my fish and seafood class during that time. We “rescued” thousands of dollars’ worth of seafood in those 5 months.

While it turned into a huge benefit for my family, this “fish-case fiasco” never should have happened. There was a combination of many factors at play, some more obvious than others: cultural expectations, including instant gratification and impulse buying, rather than planning or ordering ahead, leading to a lack of a pre-sale structure for grocers; overabundance, resulting in too much fish being ordered, just to have a large fish case that looked “full” (a full case sells better); and variety, where people expect lots of different kinds of food/fish to be available at any time, leading to more being purchased overall by retailers. We have a generation of people out-of-touch with seasonality and geographical boundaries of cuisine, leading to massive amounts of fresh fish shipped express to the Utah desert, and a culture of convenience, where throwing fish away was preferrable to spending the extra minutes wrapping it up. There are more drivers, but these are a few.

Perhaps the biggest invisible culprit is that America has developed a culture of quality without educational backing: we want the best and the finest, but we don’t always know what that is, especially when it comes to food. Additionally, we want to eat luxuries as staples and sideline traditional staple foods. The world as a whole is leaning in this direction.

This can change. If we are to meet Target 12.3, it has to change. We may need to focus on adult behaviors in the short-term, but accurate education of coming generations is key for successfully rebalancing our planet. As the old adage goes, “Give a man a fish, he’ll eat for a day; teach a man to fish, he’ll eat for a while and then take shortcuts and ruin the system. Teach a man to love to fish, and he will find a way to keep fishing for a lifetime, teach his children sustainable practices, and become a functional part of the world’s ecosystem instead of destroying it for profit.”

And he might even stop overstocking the fish case.

Sabina Michelle Säfsten Routon

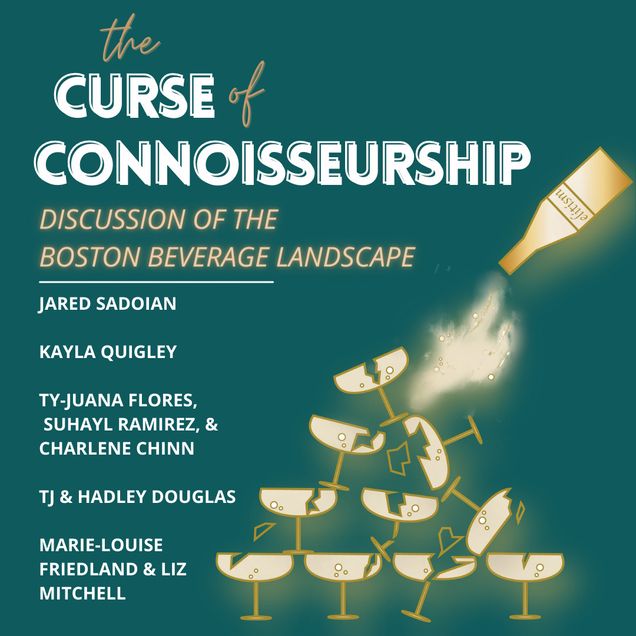

The Curse of Connoisseurship

Discussions of the Boston Beverage Landscape

With its focus on expensive luxury goods, gatekeeping, and arcane learning, the world of wine and spirits is largely exclusive. The elitism associated with these products contributes to class differentiation, with some groups gaining from the involvement while others become marginalized. The field of beverage studies offers a platform to consider these intricate and previously unexplored aspects of classmaking.

To explore the related pitfalls in today’s beverage industry, Gastronomy students Amy Johnson and Altamash Gaziyani have organized a conference, The Curse of Connoisseurship: Discussions of the Boston Beverage Landscape. The program is hosted and funded by the Boston University Office of Diversity & Inclusion as part of the 2020-2021 Learn More series focused on the theme of social class.

Structured as a series of six webinars to be held on Tuesday and Thursday evenings during the month of March, the conference will address who is othered and made invisible as a result of underrepresentation in the wine and spirits industry. Gastronomy students and alumni will host these conversations, bringing together industry professionals from across the Boston beverage scene to discuss the existing barriers present within this community.

Conference sessions will foster conversations about the language, rhetoric, spaces, and events used to discuss, share, and sell wine and spirits. This virtual conference is broken down into six different discussions which are free and open to the public. Please register here to join in the conversation.

Tuesday March 2, 6 pm: Crafting the Back Bar: Capitalism vs. Classism, with Jared Sadoian, General Manager, Craigie on Main

Thursday, March 4, 6 pm: One Foot in the Saloon: Recreating Classist Spaces, with Kayla Quigley, local representative of Flor de Cana, a fair trade certified, natural rum company.

Tuesday, March 9, 6 pm: Creating Hospitality Through Diversity, with TJ & Hadley Douglas, owners of the award-winning wine shop Urban Grape, in Boston’s South End.

Thursday, March 11, 6 pm: We Deserve, with Ty-Juana Flores, Creator/Founder, Suhayl Ramirez, Industry Attaché, and Charlene Chinn, Business Strategist, TFLUXÈ. The TFLUXÈ mission is to diversify, disrupt, and demystify the landscape of the wine industry one sip at a time through curated virtual events for a growing community of BIPOC consumers.

Tuesday, March 16, 6 pm: Reckoning with Power Dynamics in the Wine World, with Marie-Louise Friedland (Sommelier & Graduate Student) & Liz Mitchell (Advanced Sommelier, CMS)

Thursday, March 18, 6 pm, conference De-Brief Session: Let’s Discuss: Inclusivity in the Beverage Industry

Conference Registration link: https://bostonu.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJcrd-itpj0rHdbSpyOOrUvjB_6JhsAfr6Uz

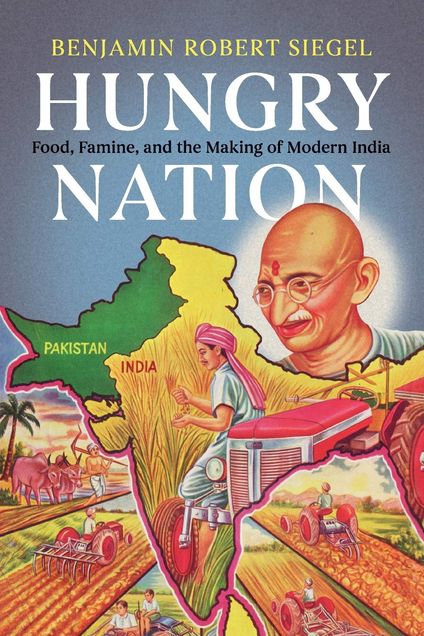

Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India

Professor Benjamin Siegel will speak in our Spring 2021 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy on his book Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India.

| Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India |

| Friday, March 26 at 12 pm, EST. |

| Online program: please register here to receive a link to the webinar. |

Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India is an ambitious and engaging new account of independent India's struggle to overcome famine and malnutrition in the twentieth century traces Indian nation-building through the voices of politicians, planners, and citizens. Siegel explains the historical origins of contemporary India's hunger and malnutrition epidemic, showing how food and sustenance moved to the center of nationalist thought in the final years of colonial rule. Independent India's politicians made promises of sustenance and then qualified them by asking citizens to share the burden of feeding a new and hungry state. Foregrounding debates over land, markets, and new technologies, Hungry Nation interrogates how citizens and politicians contested the meanings of nation-building and citizenship through food, and how these contestations receded in the wake of the Green Revolution. Drawing upon meticulous archival research, this is the story of how Indians challenged meanings of welfare and citizenship across class, caste, region, and gender in a new nation-state.

Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India is an ambitious and engaging new account of independent India's struggle to overcome famine and malnutrition in the twentieth century traces Indian nation-building through the voices of politicians, planners, and citizens. Siegel explains the historical origins of contemporary India's hunger and malnutrition epidemic, showing how food and sustenance moved to the center of nationalist thought in the final years of colonial rule. Independent India's politicians made promises of sustenance and then qualified them by asking citizens to share the burden of feeding a new and hungry state. Foregrounding debates over land, markets, and new technologies, Hungry Nation interrogates how citizens and politicians contested the meanings of nation-building and citizenship through food, and how these contestations receded in the wake of the Green Revolution. Drawing upon meticulous archival research, this is the story of how Indians challenged meanings of welfare and citizenship across class, caste, region, and gender in a new nation-state.

Benjamin Siegel is Assistant Professor of History at Boston University. His transnational archival work places South Asia at the center of global economic, environmental, and bodily transformations. Professor Siegel's work has been published in the Caravan, the Christian Science Monitor, Contemporary South Asia, Humanity, the International History Review, the Marginalia Review of Books, Modern Asian Studies, the World Policy Journal, VICE, and other journals and edited volumes. He received his B.A. from Yale University and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University, where his dissertation won the 2014 Sardar Patel Award given by the Center for India and South Asia at UCLA, honoring "the best doctoral dissertation on any aspect of modern India."

We thank the Jacques Pépin Foundation for sponsorship of this lecture series.

Diners, Dudes & Diets: How Gender & Power Collide in Food Media & Culture

The Gastronomy Program is pleased to announce that the first program in the Spring 2021 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy will feature Gastronomy Program alumna Emily J. H. Contois (MLA 2013), speaking on her recently published book, Diners, Dudes & Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture.

| Diners, Dudes & Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture |

| Friday, February 19 at 12 pm, EST. |

| Online program: please register here to receive a link to the webinar. |

The phrase "dude food" likely brings to mind a range of images: burgers stacked impossibly high with an assortment of toppings that were themselves once considered a meal; crazed sports fans demolishing plates of radioactively hot wings; barbecued or bacon-wrapped . . . anything. But there is much more to the phenomenon of dude food than what's on the plate. This provocative book begins with the dude himself—a man who retains a degree of masculine privilege but doesn't meet traditional standards of economic and social success or manly self-control. In the Great Recession's aftermath, dude masculinity collided with food producers and marketers desperate to find new customers. The result was a wave of new diet sodas and yogurts marketed with dude-friendly stereotypes, a transformation of food media, and weight loss programs just for guys.

The phrase "dude food" likely brings to mind a range of images: burgers stacked impossibly high with an assortment of toppings that were themselves once considered a meal; crazed sports fans demolishing plates of radioactively hot wings; barbecued or bacon-wrapped . . . anything. But there is much more to the phenomenon of dude food than what's on the plate. This provocative book begins with the dude himself—a man who retains a degree of masculine privilege but doesn't meet traditional standards of economic and social success or manly self-control. In the Great Recession's aftermath, dude masculinity collided with food producers and marketers desperate to find new customers. The result was a wave of new diet sodas and yogurts marketed with dude-friendly stereotypes, a transformation of food media, and weight loss programs just for guys.

In a work brimming with fresh insights about contemporary American food media and culture, Contois shows how the gendered world of food production and consumption has influenced the way we eat and how food itself is central to the contest over our identities.

Emily J.H. Contois is an Assistant Professor of Media Studies at The University of Tulsa. Her research and writing span the breadth of food, health, and identity in popular culture and media. She has appeared on CBS This Morning, BBC Ideas, and Ugly Delicious with David Chang on Netflix. She earned her PhD in American studies at Brown University and holds master's degrees in public health from UC Berkeley and gastronomy from Boston University. She lives in Tulsa with her husband and their rescue pup, Raven.

Note: anyone interested in purchasing a copy of Diners, Dudes & Diets from UNC Press can get a 40% discount using code 01DAH40.

We thank the Jacques Pépin Foundation for sponsorship of this lecture series.

New Gastronomy and Food Studies Students, Spring 2021 part 3

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Josephine Accarrino grew up loving the pleasures of the table. Food, alongside its traditions, always played a starring role in all her family get-togethers.  Her family’s old-world traditions contrasted with friends’ traditions and stories were often traded over the different ways food was celebrated in family gatherings. In Toronto, where Jo was born and bred, a car drive of 20 minutes in any direction allows access to food from myriad cultures. In Josephine’s life, food always served as a window into culture and society.

Her family’s old-world traditions contrasted with friends’ traditions and stories were often traded over the different ways food was celebrated in family gatherings. In Toronto, where Jo was born and bred, a car drive of 20 minutes in any direction allows access to food from myriad cultures. In Josephine’s life, food always served as a window into culture and society.

For the first years of her working adult life, Josephine taught grades 4 – 10 after obtaining her BSc from University of Toronto and her B.Ed from the University of Western Ontario. After her first child, she transitioned, with the help of a MSc from Drexel University, to a career in clinical research, where she successfully grew and managed a boutique research firm, and evened up the family with a second child. Lucky enough to have wound down the company just before the pandemic hit, Covid restrictions gave Josephine time to reflect on what mattered most to her. Not surprisingly, she came back to food, people and culture. In truth, these three loves never really left – travelling the world for work and pleasure afforded Josephine the deep satisfaction of delving into different cultures through their relationship with food. Josephine will never be sure if she found the Certificate Program in Food Studies at Boston University Food or if it found her; either way, she is very excited to begin this next phase of her journey.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Hannah Billingsley spent her formative years riding horses and watching Martha Stewart. She  did a gap year between high school and college in Cape Town, South Africa before ending up in NYC, where she graduated from Columbia University in 2010 with a BA in African Studies.

did a gap year between high school and college in Cape Town, South Africa before ending up in NYC, where she graduated from Columbia University in 2010 with a BA in African Studies.

A love of contemporary photography has led her down a winding career path, and she returned to her beloved Cape Town to live and work from 2013 to 2019. A few years in the art world eventually led to work in academic publishing at Pearson South Africa, which she continues today as a freelance editor, in addition to her work as a copywriter. A life-long love of pie and baking saw her introduce American-style fruit pies to Cape Town via her pie stand at one of the city's weekly food markets. She also has spent the past couple of years learning French and was able to live in France for three months in 2019, an opportunity which allowed her to start thinking seriously about studying food.

Discovering the writings of Wendell Berry, Jean Vitaux, Robin Wall Kimmerer and Clarissa Dickson Wright over the past three years has been a significant experience to say the least and intensified her belief that many of the world's problems relate to issues around food and farming. Through the certificate course at BU, she hopes to find her 'purpose' within food studies, while learning more about her particular interests in regenerative farming, proper animal husbandry, home economics and the possibility of food to function as a diplomatic tool.

As a Chinese American, food has always been a pillar to Catherine Blewer's identity. She finds nothing more comforting than a bowl  of congee. While she is biased toward Chinese food she also greatly enjoys exploring other types of cuisine. She often craves seafood and looks forward to living in Boston where she will be much closer to the Wellfleet oyster.

of congee. While she is biased toward Chinese food she also greatly enjoys exploring other types of cuisine. She often craves seafood and looks forward to living in Boston where she will be much closer to the Wellfleet oyster.

Catherine graduated from Union College majoring in Visual Arts. She also received a Certificate in Cooking from the New England Culinary Institute and has worked on the line at a couple of restaurants. She now works for a small Virtual Events company that teaches Sushi Rolling and Bubble Tea helping build out their quality assurance department and hone their creative brand.

Catherine hopes to learn as much as she can while studying at BU and further orient her career into the food world. In particular, she hopes she can apply what she learns to help the small business she works for as well as helping the restaurant community recover after the pandemic.

Beyond food Catherine really enjoys true crime, photography and a good book. She currently lives in New York where she is from with two roommates and many plants.

Sabina Michelle Routon is a polymath who doesn’t actually enjoy math all that much. She does enjoy learning languages, writing,  drumming, learning about finance, making jam, telling stories, conducting choirs, and completing the first half of any given crochet project. Because she enjoys these things, she chose not to major in any of them and instead got her B.S. degree in Family Studies, emphasizing human sexuality and family systems, from Brigham Young University. She minored in Linguistics and spun cymbals in the marching band, taking various classes in theater-makeup, rhetoric, and Russian literature so she would have something to talk about at parties.

drumming, learning about finance, making jam, telling stories, conducting choirs, and completing the first half of any given crochet project. Because she enjoys these things, she chose not to major in any of them and instead got her B.S. degree in Family Studies, emphasizing human sexuality and family systems, from Brigham Young University. She minored in Linguistics and spun cymbals in the marching band, taking various classes in theater-makeup, rhetoric, and Russian literature so she would have something to talk about at parties.

Sabina received her culinary education through the then-pioneering online program from Escoffier School of Culinary Arts; she has since earned a certificate in entrepreneurship from LDS Business College and an industry certification as a professional resume writer and career coach. She taught scores of community cooking and gardening classes in Provo, Utah, and spent many years as a caterer, recipe developer, and artisan baker. Over the years, she discovered an interest in bean-to-bar chocolate, a love for learning the use and history of spices and herbs, and an unexpectedly deep-rooted excitement about apples.

Though these interests seem disparate to some, Sabina looks forward to bringing the best of them to bear through her gastronomy studies at BU and beyond. She is passionate about community self-reliance, sustainability and hunger-relief efforts. Of all of her professional and academic interests, her deepest fulfillment comes through building systems to help individuals and communities thrive.

She looks forward to working with others to strengthen food systems around the globe, particularly in the wake of Covid-19 and other recent disasters.

Sarah Lindsey hasn’t been in school for a while. Last time she was, she was earning her BFA in theater from NYU. It was the 90’s and  the city was filled with possibilities and brunch. Five years later, with the possibilities starting to seem less likely to pay off, she took a hospitality job in the USVI. Before she knew what was happening, she was applying for a job as a chef on a charter sailing yacht. In the interview, the boat owner asked where she had worked as a chef before. She replied, “I haven’t, but I lived in NYC for 10 years and ate in a lot of restaurants, so I know how food should look and taste.”

the city was filled with possibilities and brunch. Five years later, with the possibilities starting to seem less likely to pay off, she took a hospitality job in the USVI. Before she knew what was happening, she was applying for a job as a chef on a charter sailing yacht. In the interview, the boat owner asked where she had worked as a chef before. She replied, “I haven’t, but I lived in NYC for 10 years and ate in a lot of restaurants, so I know how food should look and taste.”

Somehow that bit of bravado paid off. She got the job and realized she loved not just eating food, but cooking it. She moved on to a second yacht job, then back to land where she kept cooking and developing recipes and menus, working for a small, family run business. It seemed the next step should be starting her own small, family run business - an investment to take her through the next stage of life while raising her daughter. Turns out you need more than bravado and good food to run a restaurant these days. Without coproprate backers, or (frankly) business know-how, the restaurant came to an untimely end, leaving Sarah to rethink that next stage of life.

Sarah joins the Gastronomy program remotely from Austin, TX. Beginning with the Food Studies Certificate, she hopes to explore the field of food writing for the media. Fascinated by the effects of culture and history on perceptions of food and health, she’s looking forward to digging into ideas, learning new skills and drawing connections that help us understand the whys of our complicated relationships to food.

New Gastronomy and Food Studies Students, Spring 2021 — part 2

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Clarissa Rosinski is from sunny Riverside, California where many of her fondest family memories were related to  food. She spent a lot of time as a child in the kitchen with her great grandmother preparing fresh tortillas, refried beans, and sopas. It was with her nana that she spent time baking loaves of bread, cakes, cookies, and pies. The ideas of food, family, and culture have been interwoven ever since.

food. She spent a lot of time as a child in the kitchen with her great grandmother preparing fresh tortillas, refried beans, and sopas. It was with her nana that she spent time baking loaves of bread, cakes, cookies, and pies. The ideas of food, family, and culture have been interwoven ever since.

Clarissa left home at 19 years old to enlist into the United States Air Force. She joined with two goals in mind; see the world, and graduate college. She has done just that. Eighteen and a half years later and she has been stationed in 7 countries, visited over 32 more, and enjoyed the experiences of countless cities. Her job in the military is Services, which mainly focuses on Foodservice and lodging hospitality. Interestingly, this led her to complete her B.S. in Hotel and Restaurant Management from Northern Arizona University.

Her passion for food has always been there, but it wouldn’t be until she was in her 20s that she started to realize the truth: Food may be sustenance, but it also brings you memories and experiences with others. It’s a language of its own, but also an art. Not everyone gets it. Clarissa did not see this immediately, but she has finally realized her truth. Food is nature, it’s beauty, its art.

As Clarissa nears the end of her Military career, she looks forward to what lies ahead. She is excited to be pursuing the Food Studies Certificate and plans to continue with the full Gastronomy program at Boston University. The opportunity to continue learning about food and what inspiring notions come forth drives her to learn more.

Kelsea Knowles joins the BU Gastronomy program from Toronto as an online student. She is  currently a professional in the hospitality sector in a director level role working as the Chief of Staff and Executive Assistant to a celebrity chef.

currently a professional in the hospitality sector in a director level role working as the Chief of Staff and Executive Assistant to a celebrity chef.

She’s worked in hospitality since she was 15 years old and loves all things food from food media to eating to cooking to food waste & security. Her original plan was to work in the Visual arts sector and she has a Bachelor of Fine Arts from OCAD University. Pursuing a career in the Arts didn't offer her the same high energy, physical stimulation, and social element that hospitality did so she returned to restaurants.

After 10 years working for celebrity Chef Susur Lee, Kelsea is interested in a career shift but not yet sure in which direction. She’s hoping to expand her knowledge of food & food culture in this graduate certificate with the possibility of expanding into a Master’s degree. Once the graduate certificate is completed, she plans on complimenting her education in Food Studies with a hands-on culinary education. She’s been offered a position at Ecole Ducasse (Chef Alain Ducasse) Paris for an intensive 6 month but due to COVID-19, has been forced to defer.

Having spent the last year in and out of work due to COVID-19, Kelsea has spent a lot of time cooking and experimenting in her own kitchen and exploring the ways in which we nourish ourselves physically, spiritually & mentally all while exploring her own mixed-race identity. While her exact focus is not yet decided, her areas of interest are writing, media, gender & race studies and how they all intersect within the food world. Her current project is working on publishing a cookbook in 2023.

Kelsea is most excited about returning to an environment ripe with learning and sharing experiences with like-minded individuals.

A West Coast native, Diana Martin lives in San Francisco and comes from a career in education non-profit. Growing  up in Portland, Oregon, she made her way to Los Angeles for undergrad where she crashed head first into the awe-inspiring deliciousness that is California produce. Dining all over L.A., a love of taco trucks and avocados grew deep where it has only continued to flourish in the Bay Area.

up in Portland, Oregon, she made her way to Los Angeles for undergrad where she crashed head first into the awe-inspiring deliciousness that is California produce. Dining all over L.A., a love of taco trucks and avocados grew deep where it has only continued to flourish in the Bay Area.

The vast majority of her professional life has been with Reading Partners, but Diana has dabbled in the frozen dessert industry with titles such as "scooper", "trainee" and "gelato/barista extraordinaire." She still loves ice cream and is an avid sampler (within reason) even after giving out countless samples to eager customers.

Food takes up the majority of Diana's brain space outside of, and also during work. She loves to try new recipes and create something new from whatever leftovers linger in the fridge. Diana considers herself a darn good amateur sourdough bread baker and can't help but to find new ways to incorporate sourdough starter because it hurts her heart to compost it all.

Diana is passionate about community, laughter, staying active, sustainable practices and eating well. The Gastronomy program is an opportunity for a total career shift and Diana is eager to make connections, learn, eat, learn more, and see where this journey leads!

Mackenzie Lombardi is from central Pennsylvania, born and raised. Wanting a bigger experience than her small  town, she attended The Pennsylvania State University and graduated with a degree in Nutritional Sciences. She then came up to Boston to complete her dietetic internship at Simmons University.

town, she attended The Pennsylvania State University and graduated with a degree in Nutritional Sciences. She then came up to Boston to complete her dietetic internship at Simmons University.

During her internship she saw how individual’s food preferences were influenced by more than just taste or nutritional need. This led her to become more interested in food studies and how food choices are influenced by one’s gender, cultural background, and perceived moral value. After completing her internship, this once suburban girl decided to stay in Boston for its rich history and vast opportunities. Living in Boston has introduced her to food cuisines that she never had the chance to try back in PA, where it was either her dad’s Italian cooking or restaurants serving the typical American Cuisine. (She is happy to report that central PA has diversified their food cuisines since the early 2000’s!)

She recently became a Registered Dietitian and realized that the dietetics world wasn’t fulfilling her true interests. Enter, BU’s Gastronomy program! She is excited to examine women’s role in the kitchen and how women perceive their identify through the food they eat. Mackenzie can be found wandering grocery store isles, watching movies, or hiking in her free time.

Originally from the fertile soil of Fresno, CA, Shant Farsakian was steered towards his love of food by  his green-thumbed Armenian family. He spent much of his youth pulling fresh fruits and veggies from their backyards, often eating them straight off the trees or vines. These close, special relationships with food and flavor forged a passion that he has since been exploring with gusto.

his green-thumbed Armenian family. He spent much of his youth pulling fresh fruits and veggies from their backyards, often eating them straight off the trees or vines. These close, special relationships with food and flavor forged a passion that he has since been exploring with gusto.

While completing his B.A. in Psychology at California State University, Northridge in 2012, Shant began brewing beer with his roommate in their apartment. He fell in love with the entire process (and product) and thus began a career in craft beer, eventually moving south to San Diego to be at the heart of the movement. There he spent 4 years learning as much as he could about the sudsy amber stuff, from the recipes and flavors to the histories and cultures. With the

latter becoming his focus, Shant became a student of the culture of cuisine. He moved quickly from just beer to all foods and beverages, using his time not working in the industry to travel and taste.

A move to Denver, and a pandemic later, and Shant has decided to bolster his self-education with a formal one in BU’s Gastronomy Program. Here he plans to polish his food writing and researching skills to help him preserve not only the food and culture of his Armenian ancestry, but that of any group whose people face the threat of racism and institutionalized genocide. He believes acceptance of all food as equal is the first step to accepting all people as such.

Leading up to this moment Abby Kohn has spent nearly a decade refining her skills as a Pastry Chef at  three out of five of Manhattan’s Michelin 3-star establishments. Presently she is the Pastry Sous Chef at Thomas Keller’s Per Se. It was the demand for details, inspiring ingredients, and opportunities for collaboration that first drew Abby to the culinary world, and second made a home for her within the Thomas Keller Restaurant Group family. Much of her individual success is measured by a spirit of peer mentorship inherent within the TKRG family. At this point in her career, Abby is ready to expand her understanding of food beyond the kitchen and into the world.

three out of five of Manhattan’s Michelin 3-star establishments. Presently she is the Pastry Sous Chef at Thomas Keller’s Per Se. It was the demand for details, inspiring ingredients, and opportunities for collaboration that first drew Abby to the culinary world, and second made a home for her within the Thomas Keller Restaurant Group family. Much of her individual success is measured by a spirit of peer mentorship inherent within the TKRG family. At this point in her career, Abby is ready to expand her understanding of food beyond the kitchen and into the world.

She intends to achieve this by obtaining her MLA in Gastronomy. It is her hope that through a combination of skill, experience, and learning she can open her mind to thinking about food from another perspective. In spite of the fact that the synthesis of ideas remains open-ended. Abby is determined that she will be able to find and make connections in her learning that will ultimately create a meaningful contribution to the culinary world.

Amber Sampson is an artistic, creative, passionate, activist, public speaker, researcher and chef who  loves exploring the world through food. Always hungry, her cravings for food research started as rumblings in her youth when she became incredibly sick with a brain tumor. From her hospital bed, the escapism and beauty of food and travel TV gave her the courage to fight her illness and win. As a healthy adult, Sampson’s TV idols of Julia Child and Jacques Pépin became career heroes.

loves exploring the world through food. Always hungry, her cravings for food research started as rumblings in her youth when she became incredibly sick with a brain tumor. From her hospital bed, the escapism and beauty of food and travel TV gave her the courage to fight her illness and win. As a healthy adult, Sampson’s TV idols of Julia Child and Jacques Pépin became career heroes.

Currently, Sampson holds a degree in Cultural Anthropology and a second degree in Food Systems Sustainability. She is a trained professional Chef, with a degree in Culinary Arts and Nutrition. Using food as a universal language, her research focuses on the relationship between food and culture. Specifically, Sampson enjoys studying the anthropological relationship between food and culture in ancient times. Her work brings present day relevance to ancient meals, people and customs, giving others a taste and connection to our delicious past, revealing a more sustainable and understanding future. You can find Sampson in the warm Southwestern desert of Arizona, teaching culinary, foraging, cooking, researching, gardening, and exploring our tasty past.

New Gastronomy and Food Studies Students, Spring 2021

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful group of new students into our programs this spring. Enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

Like any good story, it started with a love of bagels. It might have been the New York in her blood, but Emily Bowers  left the city circa. 1997 and was raised in the land down under where everything is too large and trying to kill you. Florida.

left the city circa. 1997 and was raised in the land down under where everything is too large and trying to kill you. Florida.

Earning a BBA from Belmont University in Music Business and Audio Engineering, Emily found herself in Nashville with nary a job in sight. Then, her love of bagels proved useful as she began her restaurant career at the newly opened bagel shop across from the university. From there she went on to manage restaurants until the love of bagels could sustain her no more. Exhausted, Emily returned home to Florida just in the nick of time.

COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement exploded and Emily was left debating how she could best contribute to the education and reparations towards the Black and Indigenous communities in the United States. Books were ordered and read, but still she was indecisive. Then, one fateful night, she was watching Ancient Aliens with her dad (his choice, but no one was complaining) and the narrator began discussing the culture of the Maya. She paid closer attention because her favorite newly purchased book discussed the food systems of the Aztec, Inca, and Maya and she was enthralled. That’s when the question hit her: is there somewhere she could study food systems and their intersection with culture and sovereignty? And here we are. When not eating bagels, Emily can be found with her black cat Kylo Ren watching the Great British Bake Off, playing Pokémon on her Switch, or hiking local trails.

It’s the Winter of 2016, and Michael Karsh wakes from a restless sleep on the floor of a rental van barreling down the  I-95 in the wee morning hours. The van pulls into a rest stop for yet another Dunkin’ Donuts breakfast as Michael wearily begins another day on his band’s first tour.

I-95 in the wee morning hours. The van pulls into a rest stop for yet another Dunkin’ Donuts breakfast as Michael wearily begins another day on his band’s first tour.

While unremarkable at first glance, this prophetic vignette illustrates the birth of Michael’s passion for food.

Originally from Los Angeles, CA, Michael studied Music at Brown University with the intention of entering the music business. Landing a music management/publishing job in New York after college, Michael seemed to be achieving his goals; however, his creative pursuits beckoned, and he quit his job after a year to become a professional musician and hit the road with his band.

The intensive demands of professional touring forced Michael to reckon with his love of food and the cornucopia of unhealthy options on the road. The rigors of the road demanded he answer a seemingly simple question: “What is healthy food?” Michael gradually adopted a plant-based diet, and before long, completely transformed and improved his lifestyle, health and well-being, as well as his performance level. Fascinated and motivated by his personal transformation, he immersed himself in research on human biology, dietary interventions and biomarker data to explore the relationship between diet and health. Before long, his coping strategy for a physically demanding career had blossomed into one of his greatest passions.

While Michael continues to pursue music full-time in Brooklyn, NY, he hopes to synthesize his own experiences in health and wellness with BU’s Food Studies curriculum to address some of the most critical global challenges surrounding food sustainability, climate change and public health.

José Lopez Ganem is an emerging thinker on cacao and chocolate conducting interdisciplinary research drawing on the fields of history, government, management, religion, and trade. Most  recently, he developed several projects for the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute (FCCI), where in 2019/20 he was the first FCCI Latin American Cultural Exchange Fellow, representing his native Mexico. He is also a continuing instructor for FCCI Cacao Academy, an online platform developed by FCCI. He has presented his work at several scholarly forums such as Harvard University, the Culinary Institute of America, Illinois State University, the European Business School Paris, among others. His professional experience also includes an engaged period in the food industry in New York City, briefly interning at the top-rated Eleven Madison Park restaurant and at the extinct FIKA Chocolate Lab.

recently, he developed several projects for the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute (FCCI), where in 2019/20 he was the first FCCI Latin American Cultural Exchange Fellow, representing his native Mexico. He is also a continuing instructor for FCCI Cacao Academy, an online platform developed by FCCI. He has presented his work at several scholarly forums such as Harvard University, the Culinary Institute of America, Illinois State University, the European Business School Paris, among others. His professional experience also includes an engaged period in the food industry in New York City, briefly interning at the top-rated Eleven Madison Park restaurant and at the extinct FIKA Chocolate Lab.

He graduated magna cum laude from the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in 2018 with a B.B.A. in Food Business Management, accompanied by a concentration in Advance Wine Studies. During his permanence at CIA, he completed various educational and trade certifications at the Wine and Spirits Education Trust (WSET) and the Society of Wine Educators (SWE). He was awarded in 2017 with Kopf Scholarship for Wine Studies, given by Kobrand Corporation to a selected group of graduating students of Boston University, Cornell University, Johnson & Wales University, and the CIA. In 2017/18 he endured and successfully completed training in Japanese Cuisine and Culture sponsored by the Suntory Corporation and the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery (MAFF) of Japan.

In his spare time, José continues to collaborate as a non-resident research fellow at FCCI and Harvard University, both under the guidance of Dr. Carla D. Martin. You can find him behind a non-fiction book or a printed British newspaper, all while enjoying over-steeped high quality black tea.

Born in the Midwest and raised in the South, Samantha Maxwell was forced to learn how to cook when she started  exploring veganism in college. It didn’t stick, but it opened her up to a whole new world of ingredients that she had never encountered until that point.

exploring veganism in college. It didn’t stick, but it opened her up to a whole new world of ingredients that she had never encountered until that point.

After graduating with a BA in English literature, she began a freelance writing career, which provided her enough freedom to travel. This led her to a love of both quiet solo breakfasts and raucous group dinners with generous strangers. When she realized that most of her travel plans revolved around specific restaurants or dishes, she knew that she wanted to make food her focus.

Now working in food media as a writer and editor, Samantha is excited to take her interest in food to a deeper level to explore not just new flavors but also the cultures they come from and the social and political realities that undergird them. She’s interested in learning about how food connects different cultures and how we can use food to foster greater understanding and compassion for those who may live — and eat — differently than we do.

When she’s not writing or attempting a new recipe, Samantha enjoys hiking, exploring cities, doing yoga, reading, and people watching at coffee shops. She’s new to Boston and welcomes restaurant, bookstore, and plant shop recommendations.