Cookbooks & History: A Beef-Steak Pie

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Christina Grace Setio.

Historical Recipe Recreation: 1840 Beefsteak Pie

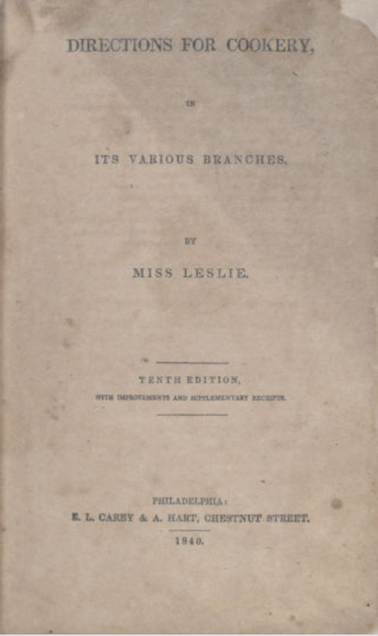

In the MET ML 630 Cookbooks and History class, we attempted to recreate a single or multiple historical recipes that are at least over a hundred years old. This project allowed for a hands-on historical analysis on the cooking production and consumption of that particular period of time. I chose an 1840 beefsteak pie recipe from a cookbook titled Direction for Cookery, in its Various Branches authored by Ms. Eliza Leslie. I accessed the digital version of the 10th edition copy where it was originally published in Philadelphia by E.L. Carey & A. Hart. Ms. Leslie was a decorated author of her time, and I find her writing style to be rather detailed and organized for an 1800 domestic cookbook. In the preface of her cookbook she has clearly stated her objective of providing American housewives with recipes adapted to the local produce and economy. She has also included measurement conversions and butchery diagram charts to aid even the most inexperienced cook.

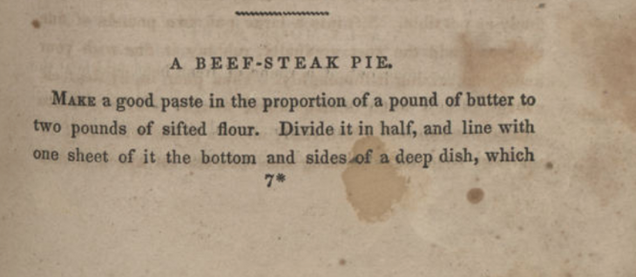

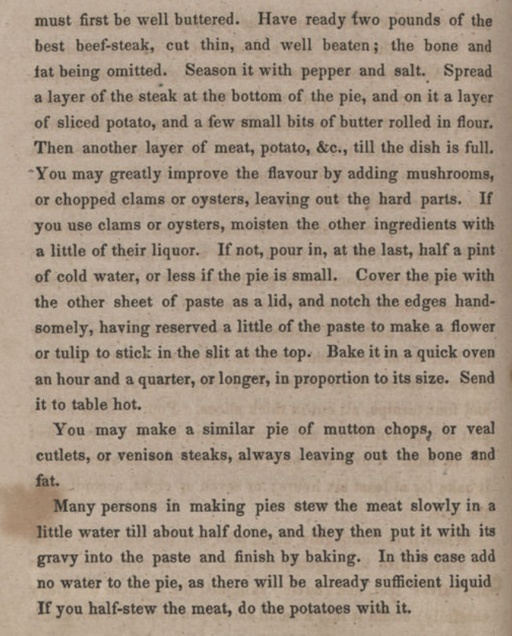

I have always been intrigued by the built and flavor composition of old fashioned American pies. Although I wanted to choose something palatable enough for modern taste buds, I also wanted to be surprised by the outcome of this recipe recreation project. Because of the current pandemic, I had to keep in mind the accessibility of procuring the ingredients within potential recipes. When I found the beefsteak pie recipe (1840, 77), I was immediately intrigued by the idea of fusing the flavor of beef and oysters in a pie.

The first challenge arose in determining the exact ingredient variety that was available or commonly used in 1840 America. As an example, the recipe for making the pie crust simply states “Make a good paste [pastry] in the proportion of a pound of butter to two pounds of sifted flour” (1840, 77). For a modern housewife, one might have endless choice of what that flour may be: bleached pastry flour, whole wheat flour, all-purpose flour, or even gluten-free flour. However in 1840, half of those flour may not even have existed or been available to the general public. Historically, whole wheat kernels must be ground using a millstone to obtain wheat flour (Campbell 2007). Since the bran, endosperm, and germ of the kernels are all ground up together, it would most resemble what we today know as whole wheat flour. Refined white flour was only available after the invention of roller mills in 1870s, thus for this recipe refined flours will not give us an accurate flavor and character. Measurement could equally be a common issue when attempting an older recipe, as old cookbooks may use different terms and also standardization was common only after the 1900s. This savory beefsteak recipe was no different, I had no exact amount to follow with some of the ingredients within the pie. Finally the materials available in an 1840 kitchen vary greatly to what we find in a 2020 kitchen. It was extremely challenging to escape the convenience of relying on industrialized produce like plastic cling wrap, a meat pounder, or a pastry brush.

The first challenge arose in determining the exact ingredient variety that was available or commonly used in 1840 America. As an example, the recipe for making the pie crust simply states “Make a good paste [pastry] in the proportion of a pound of butter to two pounds of sifted flour” (1840, 77). For a modern housewife, one might have endless choice of what that flour may be: bleached pastry flour, whole wheat flour, all-purpose flour, or even gluten-free flour. However in 1840, half of those flour may not even have existed or been available to the general public. Historically, whole wheat kernels must be ground using a millstone to obtain wheat flour (Campbell 2007). Since the bran, endosperm, and germ of the kernels are all ground up together, it would most resemble what we today know as whole wheat flour. Refined white flour was only available after the invention of roller mills in 1870s, thus for this recipe refined flours will not give us an accurate flavor and character. Measurement could equally be a common issue when attempting an older recipe, as old cookbooks may use different terms and also standardization was common only after the 1900s. This savory beefsteak recipe was no different, I had no exact amount to follow with some of the ingredients within the pie. Finally the materials available in an 1840 kitchen vary greatly to what we find in a 2020 kitchen. It was extremely challenging to escape the convenience of relying on industrialized produce like plastic cling wrap, a meat pounder, or a pastry brush.

The beefsteak pie turned out better than expected; although not visually as appealing as I had hoped, the oysters gave it more character. The idea of recreating a historical recipe seems intimidating at first, however it proves to be an exciting way to learn about the past. Not only are we are able to visualize how food may have been produced, engaging all of our senses allows for a fully submersive experience. Next project, Mrs. Seely’s Colonial Codfish Pie!

The beefsteak pie turned out better than expected; although not visually as appealing as I had hoped, the oysters gave it more character. The idea of recreating a historical recipe seems intimidating at first, however it proves to be an exciting way to learn about the past. Not only are we are able to visualize how food may have been produced, engaging all of our senses allows for a fully submersive experience. Next project, Mrs. Seely’s Colonial Codfish Pie!

Bibliography

Campbell, Grant M. 2007. “Roller Milling of Wheat.” Handbook of Powder Technology 12: 383-419. Date of access, November 10, 2020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167378507120108

Leslie, Eliza. 1840. Direction for Cookery, in its Various Branches. 10th ed. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart. Date of access, November 5, 2020. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/20#page/82/mode/2up

Cookbooks & History: Dutch Chocolate Cake

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Adrian Bresler.

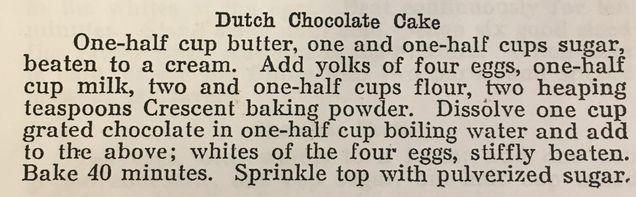

We were asked to recreate an historical recipe that was over 100 years old for our Cookbooks and History class assignment; I soon discovered that the alternatives were endless. But the Dutch Chocolate Cake recipe in “The Neighborhood Cookbook” seemed to be the right choice for me. With over 42 cake recipes (14 were variations of chocolate cake), this community cookbook, compiled and issued by The Council of Jewish Women of Portland Oregon in 1914 to fundraise for their organization, was filled with recipes written by women whose concise directions communicated to me their expertise and confidence. How could I go wrong with my choice? Their first edition, printed in 1912, sold out in ten months. And since my last attempt at baking a chocolate cake ended in a lumpy mess, now was the opportunity for redemption using a recipe written long ago by women who really knew how to cook.

We were asked to recreate an historical recipe that was over 100 years old for our Cookbooks and History class assignment; I soon discovered that the alternatives were endless. But the Dutch Chocolate Cake recipe in “The Neighborhood Cookbook” seemed to be the right choice for me. With over 42 cake recipes (14 were variations of chocolate cake), this community cookbook, compiled and issued by The Council of Jewish Women of Portland Oregon in 1914 to fundraise for their organization, was filled with recipes written by women whose concise directions communicated to me their expertise and confidence. How could I go wrong with my choice? Their first edition, printed in 1912, sold out in ten months. And since my last attempt at baking a chocolate cake ended in a lumpy mess, now was the opportunity for redemption using a recipe written long ago by women who really knew how to cook.

The Cake section of the cookbook began with a set of general instructions. Here, the editor reminded readers to measure carefully, to use an earthen dish and a wooden spoon, to never remove a cake from the oven until it is done, and to use a clean broom straw to test the cake. (Lacking a clean broom straw, I substituted a wooden toothpick).

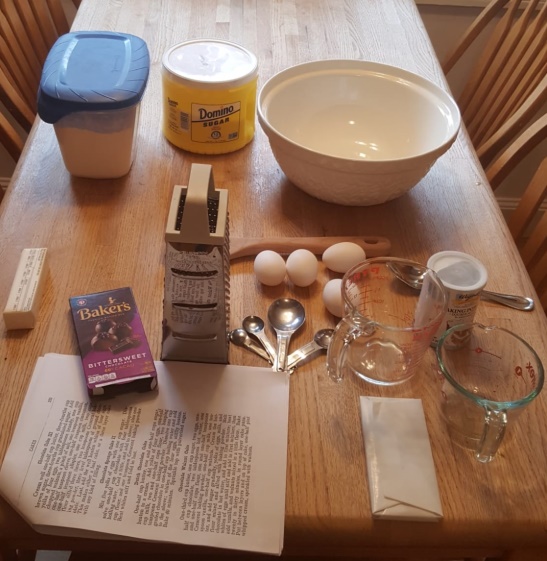

With the introduction over, I was ready to begin to bake. The recipe I chose consisted of a mere five sentences from start to finish, including a list of ingredients embedded in the short paragraph. The brevity of the directions gave the appearance of simplicity, a notion that was quickly dispelled when the baking began.

Creaming the butter and sugar with a wooden spoon, rather than using my KitchenAid mixer, took more time and muscle energy but it worked. No problem so far. The addition of egg yolks, milk, flour, and baking powder was fairly simple, too. Interrupting the action to fill the tea kettle to boil water, instead of zapping the water in the microwave, was a distraction but not really a problem. However, grating the Baker’s chocolate squares triggered an unexpected complication. The friction from the scraping caused the chocolate shavings to go airborne when the particles became statically charged. Chocolate bits flew through the air and landed everywhere including into the bowl of egg whites, which according to sentence number three, still needed to be ‘stiffly beaten’. The sight of chocolate flecks floating in the egg whites caused me some grief but just then the tea kettle whistled, announcing that it was time to melt the remaining chocolate with the boiling water. Here, the brief instructions gave me only vague guidance; I hesitated a moment before pouring the boiling water into the chocolate, rather than adding the chocolate to the water. It melted. So far, so good.

Although electric hand mixers were invented in the late 1800s, they did not become available for home use until the 1920s. To beat the (already contaminated with chocolate shavings) egg whites into a stiff froth, I turned to my mother’s old manual egg beater. Compared to the way my grandmother whipped egg whites-- with a fork-- this seemed fairly easy. As the recipe gave no further instruction, I simply folded the egg whites, now a bowl of white fluff in spite of the floating chocolate, into the rest of the batter.

With no directions regarding the type or size of the baking pan, I selected an angel food cake pan that seemed large enough to accommodate the batter. I buttered the pan to prevent sticking since cooking spray was not available to the public until the 1960s.

Remembering to return to the Cake introduction for guidance regarding oven temperature, I found that Layer cake required a ‘quick fire’, Sponge cake a ‘slow fire’, and Loaf cake with butter a ‘moderate fire’. My electric oven generates no fire. I assumed I was making a loaf cake but I was mistaken. Setting the oven at 325 degrees, I followed the fourth sentence of the directions (“…bake 40 minutes…”).

Luckily for me the fifth and last line of the instructions told the readers to sprinkle pulverized sugar on top of the cake as a finishing touch. Using confectioners’ sugar, I covered up the burned spots. The cake was a bit dry and crumbly as a result of overbaking. And the chocolate flavor was muted—perhaps too many chocolate particles flew up into the air instead of into the cake.

But at least it did not turn out to be another lumpy mess. And my family liked it. I’ve made progress.

Therefore, I owe a debt of gratitude to the now defunct Council of Jewish Women of Portland. More importantly, their cookbook helped fund the organization’s mission, which was to help new immigrants, promote women’s suffrage, provide vocational classes, and support other social issues.

Works Cited:

Conagra. 2020. “When you pick up a pan, spray it with PAM.” Pam: Our Story. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://pam.conagrafoods.ca/our-story/

Council of Jewish Women of Portland, OR. 1914. The Neighborhood Cookbook. Portland, OR: Bushong & Co. https://n2t.net/ark:/85335/m5dh3z

Kitchen Tool Reviews. 2016. “What you didn’t know about your hand mixer.” Kitchen Tool Reviews. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.kitchentoolreviews.com/2016/08/01/what-you-didnt-know-about-your-hand-mixer/.

Moon, Deborah. 2015. “Portland NCJW Dissolves, but Legacy Lives on.” Oregon Jewish Life. May 27, 2015. https://orjewishlife.com/portland-ncjw-dissolves-but-legacy-lives-on/

Scholerman, Antonia. 2018. “Portland’s Neighborhood House and The National Council of Jewish Women.” The Oregon Women’s History Consortium. http://www.oregonwomenshistory.org/portlands-neighborhood-house-and-the-national-council-of-jewish-women-by-antonia-scholerman/

Cookbooks & History: Foods of the Foreign-Born, Eggs

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to bring in to class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the second essay in this series, written by Marie-Louise Friedland.

Foods of the Foreign-Born But Make It Bland

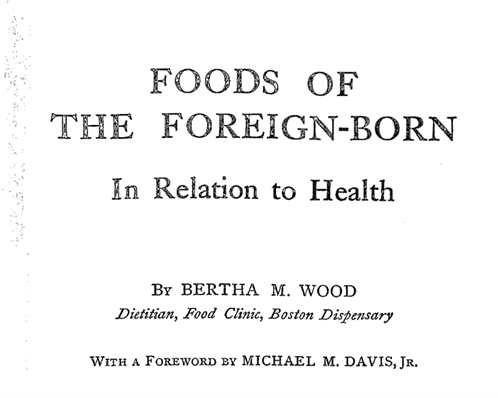

When I saw that we had to recreate a recipe from pre-1930s, my brain was swimming. I could not decide on whether I should focus on an ingredient, a time period, a cooking technique, or a specific cookbook. It was after a topic of discussion for the class that I had my epiphany. I was drawn to what recipes represent, specifically what the subtext is behind prescriptive cookbooks and the recipes within. The cookbook Foods of the Foreign Born by Bertha M. Wood was the cookbook that I was determined to cook a recipe from because I wanted to understand the mindset behind the cookbook.

As stated before, the cookbook falls under the prescriptive type of cookbook in that it acts as a prescription for how to cook to take care of one’s health. In Foods of the Foreign Born, Wood takes it to another level by recommending how to change the foods of different groups of immigrants to a “healthier” version. What I read in this is that the Americanization of immigrant cuisine is the proper way to assimilate into American society and not only will it better one’s health, but it will better one’s chances of becoming more American. As I dive more into the history of American foodways, I’ve slowly become less and less shocked by how desperately Americans wanted to “other” immigrants, but this cookbook stopped me in my tracks.

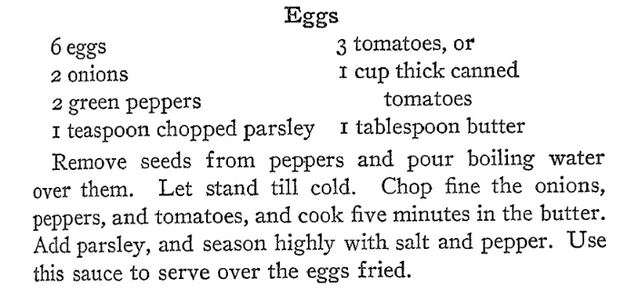

I decided to recreate a recipe called “Eggs” from the Mexican section of the cookbook. I made this decision because growing up in San Antonio, Texas I was in constant contact with Americanized Mexican food and authentic Mexican food. Those two styles were in perpetual struggle for authenticity but offered a great view of the immigrant cuisine’s treatment in the United States. Just by looking over the recipe, two things immediately jumped out at me. First, the ingredients seemed relatively bland. Second, there was no mention of any cooking utensils or materials.

I decided to recreate a recipe called “Eggs” from the Mexican section of the cookbook. I made this decision because growing up in San Antonio, Texas I was in constant contact with Americanized Mexican food and authentic Mexican food. Those two styles were in perpetual struggle for authenticity but offered a great view of the immigrant cuisine’s treatment in the United States. Just by looking over the recipe, two things immediately jumped out at me. First, the ingredients seemed relatively bland. Second, there was no mention of any cooking utensils or materials.

I gathered the ingredients at the grocery store and then started to think through the materials. I knew that the cookbook’s audience was a medical staff or a large hospital because the cookbook discusses diseases that would need medical attention if they went untreated. That fact allowed me to pick very sturdy and affordable cooking materials that would most likely be used by a staff. I decided to use all wooden utensils, a cast iron pan and ceramic bowl and serving dish. Once that was sorted the next mystery I had to solve was how to cook everything. I decided on doing it over fire to mimic a gas stove which is most likely what these medical establishments had for cooking. I used our grill that had a moveable grate so I could control the heat level under the cast iron. The recipe itself was pretty simple to recreate because everything went into the pot and as cooked down and then poured on top of six fried eggs.

I am not a master chef so it was quite easy for me to stay true to the recipe. There is always a gut instinct to stray from the recipe to make it edible, but I really wanted to get into the frame of mind of the author. I thought it was important to cook the recipe the way Wood prescribed it to be cooked because I wanted to taste it the way she intended it. This would allow me to fully understand the Americanization of a Mexican dish that was supposedly healthier than the original dish. There were a few improvisations I made that impacted the end result. I cooked it 5 minutes longer than it said to do so because I don’t think I chopped the vegetables fine enough to have them quickly cook down into a sauce. I also added a pinch more parsley in the hopes that it would add a little bit more flavor. There were also no instructions on how to fry the six eggs so I did fry them in about a tablespoon of butter in the same cast iron pan that I used to cook the vegetables in.

Once the cooking was done, I had my husband and stepfather try it and both said it was bland. My husband who is a chef and grew up in Mexico was not impressed. My stepfather added lots of hot sauce and had two helpings of it so it’s safe to say that he enjoyed it after he added his own flavor to it. The fact that the result was a plate of bland, sauteed vegetables over fried eggs was not a surprise to me considering that the recipe was intended to be healthy and help reverse some diet-related illnesses. My gut was telling me to add flavor or treat the recipe like migas to make it more enjoyable, but I knew that the whole point was to Americanize an immigrant dish under the guise of making it healthier.

The recreation of this historical recipe provided me with an incredible insight into the style of prescriptive cookbooks. The distaste for immigrant cuisine is evident in Foods of the Foreign Born although it uses the concept of healthy cuisine as a remedy for diet-related ailments to hide behind. Next time I am going to make migas.

Bibliography

Wood, Bertha M., Foods of the Foreign-Born: In Relation to Health. 1922.

Boston, MA: Whitcomb & Barrows.

Recipe appears on page 11.

Cookbooks & History: 1836 Rich Rice Pudding

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the first essay in this series, written by Sarit Sadras Rubinstein.

1836 Rich Rice Pudding

There is nothing like a comforting rice pudding. Whether served warm or cold, the few simple ingredients and the flavors they yield make it a great dessert. And with the fact that it is also filling, you get a winning dish.

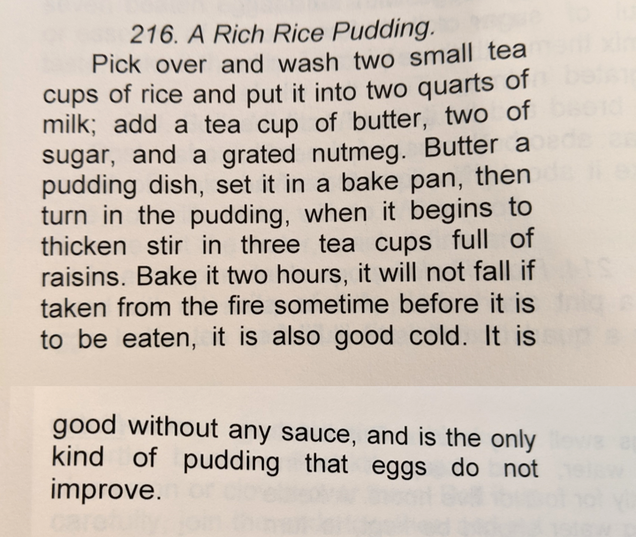

It was raining outside when I searched for a recipe to recreate for this project for the Cookbooks and History class. Since I already had a copy of the book The New England Cookbook (1836), I decided to look through the recipes and see if I liked one. Even though it may have been tempting to try a recipe such as the “pressed head” (cooking a pig’s head), I thought it would be best for everyone's sake if I chose a less exotic recipe. So when I suddenly noticed the recipe for “a rich rice pudding,” I knew this was it. It was a perfect match for the day’s weather.

Even though rice pudding is supposedly not too complicated to make, there are so many versions of it, meaning each recipe can yield very different results -- starting with the cooking process, the texture, sweetness, and even the overall look of the dish. I was curious to see how they made it during the 1800s and what it would taste like.

The recipe was quite short in length, but once reading it there were a few questions that popped up for me even before making anything. Some of them were regarding the ingredients. For example, what kind of rice were they using back in the 1800s? There are so many kinds of rice I can choose from (some are long-grain, medium-grain, white, brown). I decided to go with medium-grain rice since this is the one I usually use for rice pudding.

Some questions were about measuring. For example, there was no specific amount for how much nutmeg to add. Another example is the measuring tools and dishes that were used. What was a teacup measurement? What was a pudding dish? Unfortunately, I had no idea what those were back then and what are their equivalents in today’s time.

The biggest question, however, was about the cooking and the baking process. There was not enough information given in the recipe about the first step of the cooking. I just assumed they would like me to cook the pudding on the stove (or the fire back in the 1800s) until it thickened. Then, there was no information at all about the baking process, besides the overall baking time of two hours. There was not even a general idea of what heat (high or low) to use, which I had to guess again, and decided on 350F.

Once I figured out the ingredients, the amounts, and answered some of the questions (by making educated guesses), I could start making the recipe. The first few steps were not that complicated. I simply added the ingredients except for the raisins to the saucepan. But then, the recipe stated that the mixture needed to thicken. I assumed they meant this should happen while it was on the stove, so this is what I did. I kept it on medium heat until the rice was partly cooked. At this point, it felt like the pudding had slightly thickened. It is then when I added the raisins as the recipe stated, transferred the pudding to a buttered dish, and put it in the oven. The recipe is also quite large, so I ended up with two dishes of rice pudding.

As mentioned above, no instructions were given about the baking besides the total baking time. However, whereas the recipe said two hours at 350F, it took only 50 minutes until the pudding was completely cooked. Once done, the pudding was golden and brown on top, and all the liquid (milk) was absorbed in the rice. It smelled really good. The rice was soft, and the pudding was very sweet, even too sweet to my family’s taste (and we love sugar in our house). That said, I would say this recipe overall was a success. It might scream for adding cinnamon and vanilla (and cutting off some sugar), but I was quite impressed by how good it was, considering it is an 1836 recipe.

As previously mentioned, the recipe yielded two dishes of rice pudding, and also had some little extra in the saucepan. I decided to experiment with the leftovers in the saucepan, and while the two dishes of pudding were baking in the oven, I continued to cook the leftovers on the stove, as this is my regular cooking method for rice pudding. The texture became more like a porridge (and not solid, as in the baked version), and again very sweet. Once again, a successful result.

Overall this was a very interesting assignment. Going through the procedure of actually cooking the recipe teaches you a lot about the process of cooking, the available ingredients, and kitchen tools, and it raises questions that might have been missed by just reading the recipe. Rice pudding was always a favorite of mine. It always makes me smile and brings me back home, to my mom’s recipe, and my grandma’s recipe. Even though I would declare the 1836 recipe as a successful one, I will stick with my mom’s recipe for rice pudding. But whatever recipe you may choose, I guess one cannot really go wrong with a mixture of butter, milk, and sugar, right?

Bibliography

Kellscraft Studio. 2011. The New England Cook Book: A Young Housekeeper’s Guide. Originally published in 1836. Canaan, Maine.

Course Spotlight: Food Waste

Steven Finn will be teaching MET ML626 A1, Addressing Food Waste for a Sustainable Food System, during the Spring 2021 semester. Steven Finn is Vice President for Food Waste Prevention at Leanpath, Inc. and Co-founder and Managing Director for ResponsEcology, Inc.

Food waste is a hot topic but not a new one. Some wasted food is the sign of a healthy system—if there were exactly enough calories produced to meet each of our needs, there would be mass starvation, riots, and hoarding as we all scrambled to get our share. But by some estimates, food loss and waste account for nearly 40% of the food produced. How much wasted food is too much? At the same time this food is wasted, food insecurity is everywhere, even on BU’s campus. Is all wasted food “trash?” Need it be? Why is food wasted and where along the supply chain is it wasted? What are the ethics of donating surplus food/waste/trash of those who have too much to those who don’t have enough? This hybrid course explores the history, culture, rhetoric, and practicalities of wasted food, from farm, through fork, to gut (is overeating a form of food waste? What about wasting micronutrients by converting them to ultraprocessed foods?). Each week includes readings, discussion, application activity, and a guest lecture from a food system practitioner. Students will work together to develop practical solutions in a final project.

This 4-credit course will take place on Thursdays from 6:00 to 8:45 PM. The course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Please contact gastrmla@bu.edu for more information.

Course Spotlight: Sociology of Taste

Are you still looking to complete your Spring 2021 schedule? Connor Fitzmaurice will be teaching Sociology of Taste (MET ML 716 A1) on Thursday evenings.

Taste has an undeniable personal immediacy: producing visceral feelings ranging from delight to disgust. As a result, in our everyday lives we tend to think about taste as purely a matter of individual preference. However, for sociologists, our tastes are not only socially meaningful, they are also socially determined, organized, and constructed. This course will introduce students to the variety of questions sociologists have asked about taste. What is a need? Where do preferences come from? What social functions might our tastes serve? Major theoretical perspectives for answering these questions will be considered, examining the influence of societal institutions, status seeking behaviors, internalized dispositions, and systems of meaning on not only what we enjoy–but what we find most revolting.

If this course sounds interesting to you, please find registration information below.

MET ML 716 A1, Sociology of Taste, will meet on Thursday evenings from 6 to 8:45 PM, beginning on January 28th. Registration information can be found here.

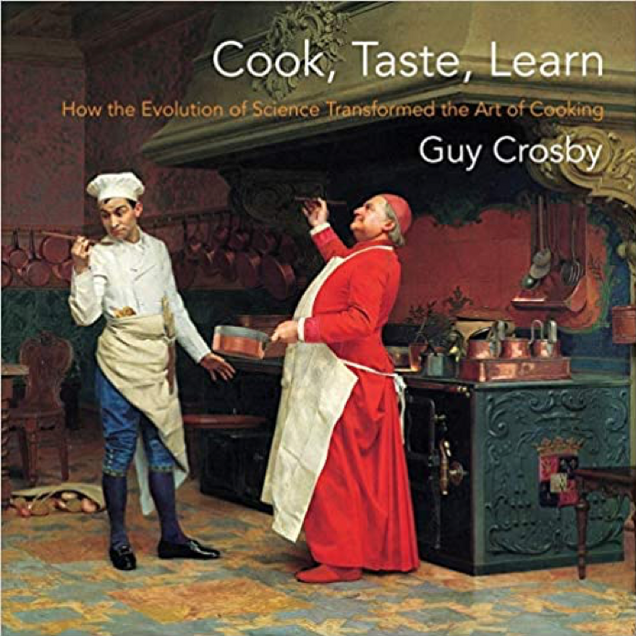

Pépin Lecture Series, Cook, Taste, Learn: How the Evolution of Science Transformed the Art of Cooking

Friday, December 4 at 12PM, register here.

Our final Pepin Lecture for the semester will feature a presentation by Guy Crosby and a cooking demonstration with Val Ryan.

Cooking food is one of the activities that makes humanity unique. It’s not just about what tastes good: advances in cooking technology have been a constant part of our progress, from the ability to control fire to the emergence of agriculture to modern science’s understanding of what happens at a molecular level when we apply heat to food. Mastering new ways of feeding ourselves has resulted in leaps in longevity and explosions in population―and the potential of cooking science is still largely untapped.

In Cook, Taste, Learn, the food scientist and best-selling author Guy Crosby offers a lively tour of the history and science behind the art of cooking, with a focus on achieving a healthy daily diet. He traces the evolution of cooking from its earliest origins, recounting the innovations that have unraveled the mysteries of health and taste. Crosby explains why both home cooks and professional chefs should learn how to apply cooking science, arguing that we can improve the nutritional quality and gastronomic delight of everyday eating. Science-driven changes in the way we cook can help reduce the risk of developing chronic diseases and enhance our quality of life. The book features accessible explanations of complex topics as well as a selection of recipes that illustrate scientific principles. Cook, Taste, Learn reveals the possibilities for transforming cooking from a craft into the perfect blend of art and science.

Guy Crosby is an adjunct associate professor at Harvard University, and formerly an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and Food Science at Framingham State University. Prior to his work as a professor he spent thirty years in the food industry at FMC Corporation and Opta Food Ingredients, Inc. He is the co-author of The Science of Good Cooking (2012) and Cook's Science (2016).

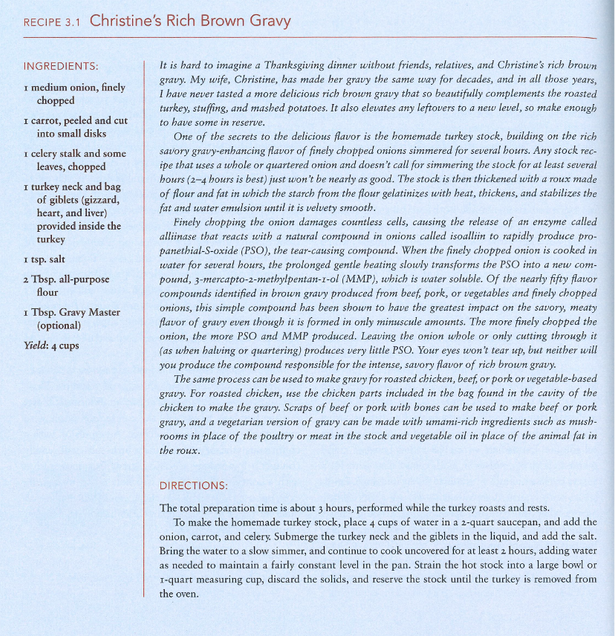

Christine's Rich Brown Gravy Recipe:

Pépin Lecture Series, Recipes and Remembrances of Fair Dillard

Friday, November 20 at 12 pm, register here

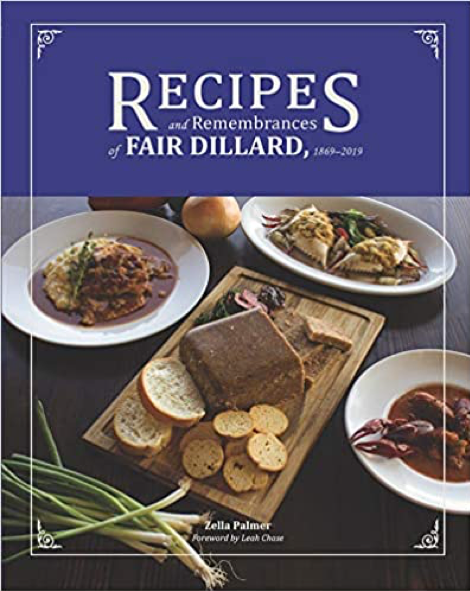

Our second Pepin Lecture for the semester will feature Zella Palmer, chair and director of the Dillard University Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture, speaking on her book Recipes and Remembrances of Fair Dillard. The book is a compilation of research and recipes related to Dillard University, one of New Orleans’s historically black colleges and universities, and one that is central to the history of the Civil Rights Movement, education, and the cultural identity of the city.

This cookbook shares over eighty years of international and indigenous New Orleans Creole recipes collected from the community, friends of the university, campus faculty, staff, and students, providing readers with a glimpse into the rich food culture of African-Americans in New Orleans. We were pleased to find that one of these recipes, Howard and Sue Bailey Thurman's "12th Night Wassail" reflects a connection between Boston University and Dillard University. In recognition of these ties, Dr. Katherine Kennedy, Director of Boston University's Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground, Dean Kenneth Elmore, Associate Provost and Dean of Student Life, and the staff of the Thurman Center recorded this video demonstration of the recipe:

12th Night Wassail

Ingredients:

- 1 Gallon Apple cider

- 2 4-inch sticks of cinnamon

- 1 quart of orange juice

- 4 tablespoons of whole cloves

- 1 quart of pineapple juice

- 4 tablespoons whole allspice

- 1 cup of lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon of mace

- 1 cup of lime juice

- 1 teaspoon of freshly ground nutmeg

- 1 pint of sugar

- 1 quart of canned spiced crabapples

Directions:

Mix all fruit juices and spices together, heat slowly and simmer for 15 minutes, being careful never to bring to a boil. Add bright red canned spiced crabapples and continue heating 5 minutes longer. Put an apple for each serving in individual punch cups or silver bowl. Drink as you assemble around the fire to watch the glowing embers from the “burning of the holiday green.”

“We have served some variant of this recipe on each occasion since the Twelfth Night celebration was established in our home twenty-five years ago. Traditionally there must be the balance in taste of five fruits and five spices. However, the real ‘magic’ for success in the formula comes at the moment when the hostess stirs into the mixture deep thoughts and wishes for the happiness and well-being of the community of friends with whom we are all united, in every crack and cranny of our world.”

Howard and Sue Bailey Thurman

Course Spotlight: Food and Public History

Got Food? Got History? Go Public.

Food and Public History, Spring 2021

In Food and Public History (4 cr), we will examine interpretive foodways programs from museums, living history museums, folklore/folklife programs, as well as culinary tourism offerings, "historical" food festivals, and food tours. Our goal is to compare different approaches to teaching the public about history or cultural heritage using food. How do we best engage the public? How do we demonstrate the relevance of food as both a historical subject and as a topic of interest today? Through different approaches to public history, can we connect our audience to issues that are so critical today—the future of food movements, for example, or the preservation and understanding of cultural difference? How can we successfully engage the public, whether through displays, tours, or interactive/sensorial experience?

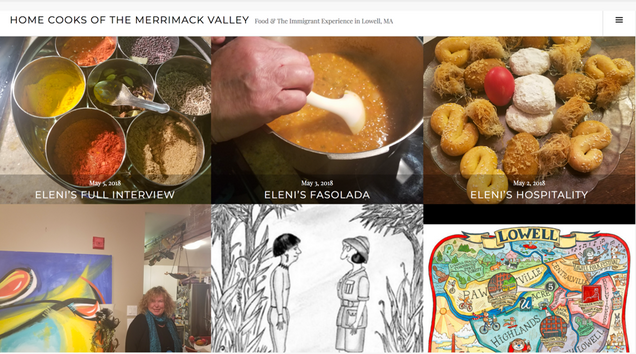

This is a project-based course involving experiential and hands-on learning opportunities. Student will continue to participate in a semester-long group project, entitled Home Cooks in the Merrimack Valley, in which students will interview domestic cooks from a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds and then incorporate those interviews into an online exhibit.

Hope you will join us!

For more information, contact kmetheny@bu.edu.

Dr. Karen Metheny, Senior Lecturer in the Gastronomy Program, will teach MET ML 623, Food and Public History, on Wednesday evenings in the Spring 2021 semester, beginning on January 27. Registration begins on November 21 and is open to degree candidates in the Gastronomy Program, as well as to non-degree students. Spring classes at Boston University are available to remote students in Boston University's "Learn from Anywhere" course mode.

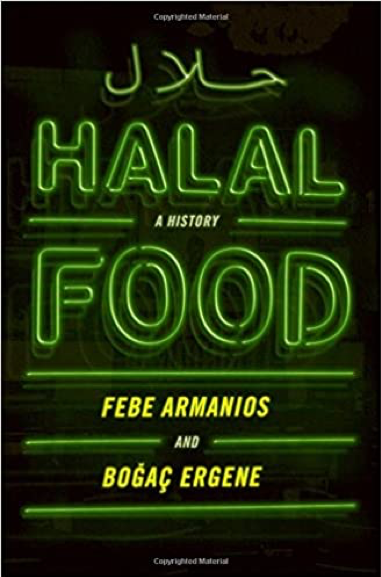

Pépin Lecture Series, Halal Food: A History

Friday, November 13, Noon to 1 PM

Speakers: Febe Armanios and Bogac Ergene

Food trucks announcing "halal" proliferate in many urban areas but how many non-Muslims know what this means, other than cheap lunch? Here Middle Eastern historians Febe Armanios and Bogac Ergene provide an accessible introduction to halal (permissible) food in the Islamic tradition, exploring what halal food means to Muslims and how its legal and cultural interpretations have changed in different geographies up to the present day.

Historically, Muslims used food to define their identities in relation to co-believers and non-Muslims. Food taboos are rooted in the Quran and prophetic customs, as well as writings from various periods and geographical settings. As in Judaism and among certain Christian sects, Islamic food traditions make distinctions between clean and impure, and dietary choices and food preparation reflect how believers think about broader issues. Traditionally, most halal interpretations focused on animal slaughter and the consumption of intoxicants. Muslims today, however, must also contend with an array of manufactured food products--yogurts, chocolates, cheeses, candies, and sodas--filled with unknown additives and fillers. To help consumers navigate the new halal marketplace, certifying agencies, government and non-government bodies, and global businesses vie to meet increased demands for food piety. At the same time, blogs, cookbooks, restaurants, and social media apps have proliferated, while animal rights and eco-conscious activists seek to recover halal's more wholesome and ethical inclinations.

Covering practices from the Middle East and North Africa to South Asia, Europe, and North America, this timely book is for anyone curious about the history of halal food and its place in the modern world.

Febe Armanios is Professor of History at Middlebury College and the author of Coptic Christianity in Ottoman Egypt (OUP, 2011).

Bogac Ergene is Professor of History at the University of Vermont. He is the author of Local Court, Provincial Society and Justice in the Ottoman Empire and co-author of The Economics of Ottoman Justice.

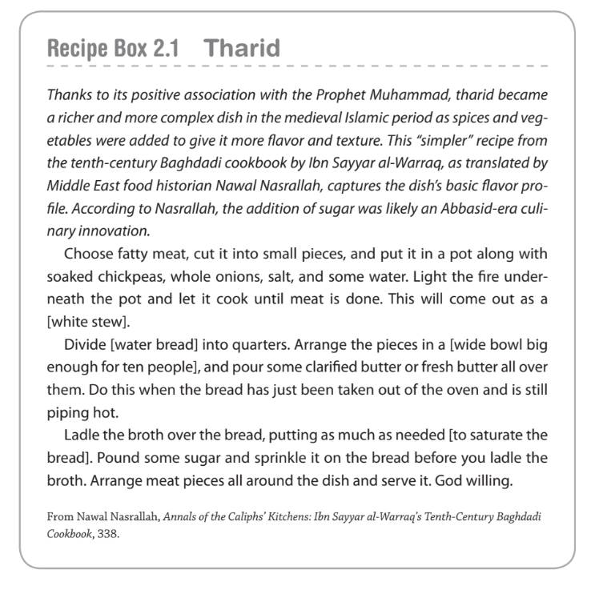

Recipe from the book

Still need to sign up for the event? Register here.