Declining Industrial Disruption

By James Bessen, Erich Denk, Joowon Kim, Cesare Righi

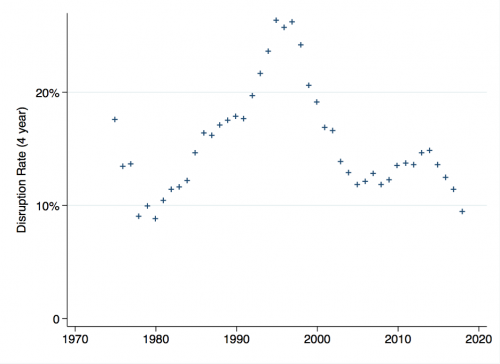

Joseph Schumpeter argued that “creative destruction” was key to spurring economic progress—small and innovative businesses disrupt industry leaders by bringing new and better and less expensive products. Economic dynamism and competition between firms drives growth and productivity, with new leaders displacing older firms and pushing the economy forward. However, recent research by TPRI shows industries are increasingly less dynamic in this regard than they once were, evidenced by decreased turnover among the largest firms. Figure 1 shows the likelihood that a firm in the top four leaders of its industry (ranked by sales) will no longer be a leader four years later. Since 2000, a firm that reaches the top of their industry is increasingly more likely to maintain their dominance, potentially creating imbalances in market power, high barriers to entry, and slower growth. These outcomes have implications for maintaining a competitive economy. Identifying and evaluating potential causes of declining disruption is crucial for policymakers concerned with competition and economic dynamism.

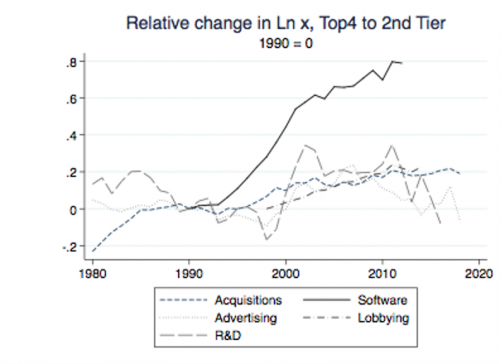

TPRI’s research investigates potential explanations for these declining hazard rates. Stories of increased mergers and acquisitions, changes to economies of scale, research and development investment, and lobbying activity all could contribute to increased persistence in an industry. Analysis shows the gaps between top firms and second tier firms on these metrics have not changed contemporaneously with declining hazard rates. Rather, leading firms’ relative investments in intangible capital has exploded. Perhaps large firms receive a greater return to intangible investments relative to their competitors. The gap in proprietary software investment is particularly large, potentially contributing to decreased displacement hazard.

Why would software investment influence Schumpeterian competition? Some examples show the effects that in-house software and IT investments can have. Amazon and Wal-Mart, for example, invest heavily in IT to improve their inventory management and reduce product delivery times. Large manufacturers invest in CAD/CAM tailored specifically to their manufacturing needs. Google and Facebook invest in algorithms to better target consumers and leverage the huge amount of data available to them, while financial companies can likewise develop software to better serve their existing customers and target new ones. Each of these companies can then use their proprietary IT developments to tailor their products and services, differentiating themselves from competitors in new ways.

Another line of research explores the relationship between markups and concentration, both of which have grown since the 1980s. TPRI’s paper suggests, perhaps counterintuitively, that markups are in fact associated with greater industrial dynamism as measured by hazard rates. Markups likely measure static price competition better than the dynamic technological competition relevant to Schumpeterian competition.

While hypotheses of “killer acquisitions”, lax-antitrust enforcement, or increased economies of scale are compelling in some cases, the overall evidence is most consistent with the role of proprietary software investment as the cause for declining industrial dynamism. Enabled by new technology, leading firms made large investments in managing complexity to improve the quality of their products and services,

differentiating themselves from rivals and creating a “natural oligopoly.” These investments can account for most of the decline in hazard rates and it appears that the relationship is causal.

New technologies are certainly still disruptive in a broad sense. For example, the entire newspaper industry is being disrupted. But Schumpeterian disruption of leading firms has waned. Now, it seems, information technology allows dominant firms to suppress their own “creative destruction,” decreasing disruption in this particular dimension. Whether this phenomenon is, on balance, a positive for society is unclear. Dominant firms may improve user experiences and product quality but may do so to the point of “business stealing.” It remains to be seen how today’s productivity benefits may diffuse across the economy or what challenges future innovators will face. Clearly, these dynamics do not represent conventional antitrust problems and do not call for typical antitrust policy responses. This research provides methods to measure changes in displacement hazards which will be helpful for researchers and policymakers alike.

Click here for the full version of the paper.