Course Spotlight: Culture and Cuisine of the African Diaspora

An invitation from Corinne DaCosta, Professor for Culture and Cuisine of the African Diaspora:

Hello,

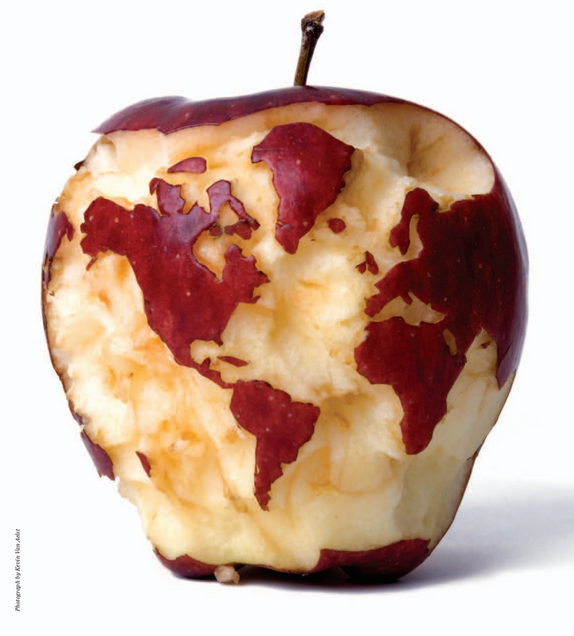

As I think about the world today, yesterday, and the tomorrows that are in the future; the cycles, connections, and continuances are what captivate my attention. Our mental muscles are searching for and connecting the dots that were left by our foremothers, forefathers, and ancestors. The dots are us and are within us, and shape our world. Understanding your place on the planet begins for a lot of people in the kitchen or on their plate. Culture, society, unwritten, unspoken rules, and laws often say ‘you’ are ‘this’ so ‘you’ eat ‘that’. As it is our brains attempt to connect and understand. We should not feel bad for this type of thinking or rationale, but we must challenge ourselves to look beyond, look deeper at how these classifications happen, and reframe them if need be. Food, its culture, and personal identity are intrinsically linked for many reasons, but one that is rather simple is that the act of eating is a bond with self. An experience that involves the earth, ‘self’, and at times everyone all across the globe.

Eating is an intimate relationship between tangible and tactile that is transformed into embodied energy. As far as diaspora connections one that is personal to me is the link between the drink of the south, Sweet Tea, and the fermented beverage that is all the rage, Kombucha. As someone who was raised with southern sensibilities, my after-school snacks were often accompanied by a glass of sweet tea, made by my great-grandmother. She would make weekly batches to never run out and quench the thirst of my rather large extended family. To make kombucha one must first make sweet tea, then add patience, a SCOBY, and some time. I often ponder on how this serves as an allegory for the African diaspora. How something was coveted, then fermented with numerous experiences, innovations, global explorations, and institutions to be changed into something different but beautiful, a little funky, but ‘good’. I am most familiar with the ‘black’ American or African American diasporic reality, but from my research, this seems to apply to other facets of the vast global community that is the African diaspora. My mother and I now brew kombucha, and we begin at the stove as my great-grandmother would with tea bags and sugar. The versatility of Kombucha reflects the diaspora as well, there are many flavors, colors, and tastes that serve everyone who would like a glass. If you are parched and would like a refreshing perspective on the cuisine and culture of the African diaspora, then perhaps this course is one that you will enjoy and I invite you to take it with a few grains of salt and a glass of Sweet Tea or Kombucha.

accompanied by a glass of sweet tea, made by my great-grandmother. She would make weekly batches to never run out and quench the thirst of my rather large extended family. To make kombucha one must first make sweet tea, then add patience, a SCOBY, and some time. I often ponder on how this serves as an allegory for the African diaspora. How something was coveted, then fermented with numerous experiences, innovations, global explorations, and institutions to be changed into something different but beautiful, a little funky, but ‘good’. I am most familiar with the ‘black’ American or African American diasporic reality, but from my research, this seems to apply to other facets of the vast global community that is the African diaspora. My mother and I now brew kombucha, and we begin at the stove as my great-grandmother would with tea bags and sugar. The versatility of Kombucha reflects the diaspora as well, there are many flavors, colors, and tastes that serve everyone who would like a glass. If you are parched and would like a refreshing perspective on the cuisine and culture of the African diaspora, then perhaps this course is one that you will enjoy and I invite you to take it with a few grains of salt and a glass of Sweet Tea or Kombucha.

Stay Sharp,

Corrine DaCosta

Professor for Culture and Cuisine of the African Diaspora

Culture and Cuisine of the African Diaspora (MET ML 629) is a 14-week online course, beginning on January 25. This 4-credit course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Registration information can be found here.

| Course Description: The foodways of the people displaced from the African continent are interwoven with many societies, cultures, and cuisines across the globe. In this course, we will study five geographic regions of Africa; north, central, east, west and south. The list of the countries that encompass each region will follow. Cookbooks, maps, songs, poems, and even some folklore will be used as texts to analyze and add context to the history of the people of the diaspora. This course will have real, and courageous, and respectful conversations including race and power and how those two elements are embedded into the food systems in North America, Central America, South America, the Caribbean and Europe. We will trace ingredients that came with the enslaved people and track their integration into cuisines and cultures (agriculture, pop culture, aquaculture etc.) as a collective group and then independently as a capstone course project. |

Cookbooks & History: Lemon Faludhaj

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to bring in to class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the final essay in this series, written by Salma Serry.

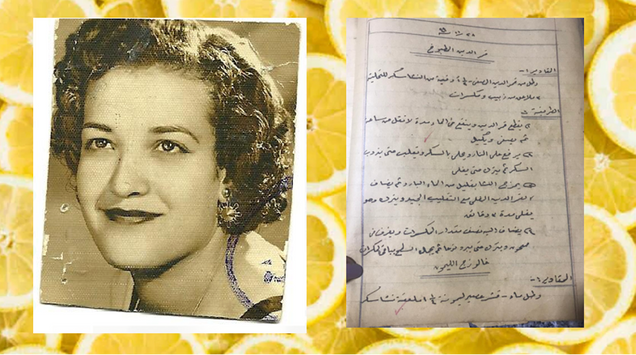

She was always the first one to wake up in the house. I would get up around 7’oclock in the morning -despite it being the summer holiday- and I would find teita Samira (teita: grandma) sitting in her bright little sewing room singing along with her little portable radio. She had a beautiful voice and she loved singing while doing chores in the house. After flipping through some German Burda fashion magazine for patterns or rummaging through her cookie-tin that turned into a sewing box, she would head to the kitchen to make breakfast and start with her lunch preparations. The kitchen was her empire. That was where she would spend hours tirelessly putting together wonderful creations for every day meals, big weekend family lunches and glorious birthday table spreads, the likes of which were- and still are- hard to find in bakery shops.

A few weeks ago, I called my mother in Dubai to ask her about some cookbooks that teita had given to my aunt before she passed away, and to my surprise, she remembered recently finding an old notebook which teita had given her when she first got married, about thirty years ago. She wrote the notebook herself when she was just about twelve years old in 1949 in school as part of her home economics subject. It was fascinating to know of its existence, having spent years searching around Cairo for old recipe collections and begging owners to let me take a look at them or borrow them for my research. Little did I know, I had one by my very own grandmother lying around in the house I grew up in.

Forty-seven recipes. Every recipe is dated. Her handwriting is so neat and meticulous, one would never guess it’s by a twelve-year-old. Unfortunately, the notebook has lost its cover, so the first and last pages are barely hanging in place, with many tears and a lot of little splatter-stains that have turned a homogenous brown over the years. The insides are intact and in good condition. Almost all recipes are marked with a red check and, in some places, they read “well-done” and “your efforts are appreciated.” I suppose these comments must have been written by her teacher.

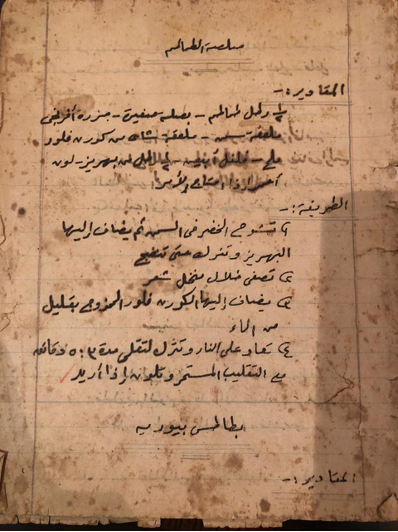

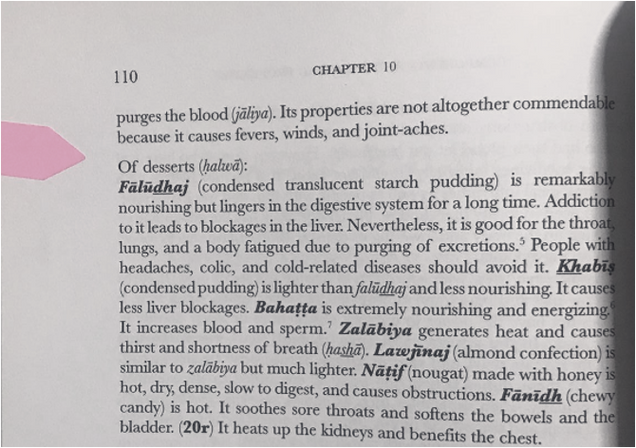

As I flipped through the delicate pages and the recipes that vary from French Baton Salé (localized with a sprinkle of cumin seeds) to traditional Eid Kah’k cookies, I stopped at a rather peculiar recipe title: Lemon Faludhaj (Faludhaj: starch-based pudding). You see, I have never seen it any of the modern or contemporary cookbooks of Egypt nor have I heard any Egyptian speak of it. My own limited knowledge of it is from two sources, each a thousand years apart from the other. The first is my experience having grown up in Dubai where Indian-style cafeterias sell a street dessert named Faloodeh/Falooda made up of thin starch noodles swimming in a semi-frozen syrup- and sometimes icecream- topped with fruits and nuts. I later came to know that it is widely popular in Iran, India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. But my knowledge of it remained limited within these geographies until I found it in a 10th century medieval cookbook from Baghdad!

In fact, the 900-something-page book, which today is translated into English by Nawal Nasrallah, features an entire chapter dedicated to only faludhajs: Faludhaj for the Caliphs, Faludhaj for the Princes, Chewy Faludhaj, Thick Faludhaj and the list goes on. In her notes, Nasrallah explains how, etymologically, the word is derived from the Persian paluda, which means among other things “strained,” translucent, and of a jelly-like consistency. She notes that the chewy type of faludhaj is very close to today’s “Turkish delight” which we call in Arabic Rahat Al Hulkum (Arabic for throat’s comfort), and which I believe has been translated into Turkish to to “lokum” (note the phonetic similarities between hulkum, meaning throat in Arabic and Turkish name for the dessert,“lokum”).

The same book generously provides medicinal advice and food characteristics based on the humoral system (see Galen’s humoral theory). According to the book, Faludhaj has characteristics that are especially “good for the throat,” lungs, and fatigued bodies. And interestingly, my aunt tells me that teita used to make faludhaj whenever any of her children had a sore throat. She distinctly recalls a time when she was about 8 years old and had her tonsils removed when teita made her some in strawberry flavor. How can a piece of knowledge travel through a thousand years? And perhaps more interesting, how does it die out within two generations (between my grandmother and my rather clueless self) in a span of 50 years after having survived more than a thousand years? Almost no one I know in Egypt recognizes the recipe anymore.

In any case, I went ahead to try out teita’s recipe below which was incredibly quick to prepare with minimal ingredients, but for some reason it did not specify whether a tablespoon or teaspoon is needed for the amount of cornstarch. The unit used for measuring water is a pound (that was before Egypt changed to metric system later in the 70s)- which equates to almost two cups of water. I started out with one teaspoon and ended up having to use 4.5 tablespoons to get to a thick pudding consistency. Maybe they had a stronger type of cornstarch? In comparison to the 10th-century recipe, the starch used is wheat-based, it calls for sesame oil as well as honey instead of sugar in addition to infusing saffron for coloring and perfuming.

Lemon Faludhaj

Ingredients:

2 cups of water

Juice of 1 lemon and its zest

1.25 spoon of cornstarch (I ended up having to use 4.5 tbsp)

Sugar (recipe doesn’t specify amount but I used 5 tbsp)

Instructions:

Melt cornstarch in cold water.

Rub the sugar into the lemon juice.

Add the sugar and lemon juice mix into the water along with the zest and bring to a gentle simmer.

Add the cornstarch mix and stir well continuously under low heat until the starch is cooked.

Pour into bowls and garnish with nuts if desired.

After leaving it to sit overnight in the fridge, I tried it the next day and it had a good pudding consistency. It was really rather refreshing - good to pair after heavy dinners perhaps or as a summer snack. If I were to make a few tweaks, I would only use half the amount of zest as it was a little overpowering and slightly bitter, and I would also experiment with it again replacing sugar with honey and adding a little sesame oil or some fat as the medieval recipe calls for – something a colleague also pointed out that could enhance the thickening process (thank you Sarit!).

All in all, it was a fascinating experience. A reliving of the past. A reenactment of imagined histories. It made me think of my grandmother as a little girl in school perhaps learning to cook with starch for the first time. It made me think of my aunt finding cooling comfort in its soft and gentle texture after her tonsil operation, a medieval maid preparing it for a sick little prince, and an Abbasid caliph enjoying its saffron-perfumed silkiness in his palace garden after a hearty lunch. All these people and places connected with this creation that carries a name of a dish with variations still popular in the Arab Gulf, India, Turkey, and Iran. And I have my late teita, Samira, to thank for extending this link to me.

Bibliography

Attia, Samira. 1948-1949. Personal Home Economics School Notebook. Cairo.

Works cited

Ibn, Sayyār -W.-M. N, Nawal Nasrallah, Kaj Öhrnberg, and Saḥbān Murūwah. 2007. Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens: Ibn Sayyār Al-Warrāq's Tenth-Century Baghdadi Cookbook. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill NV.

Cookbooks & History: Stewed Pumpkin

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Kris Kaktins.

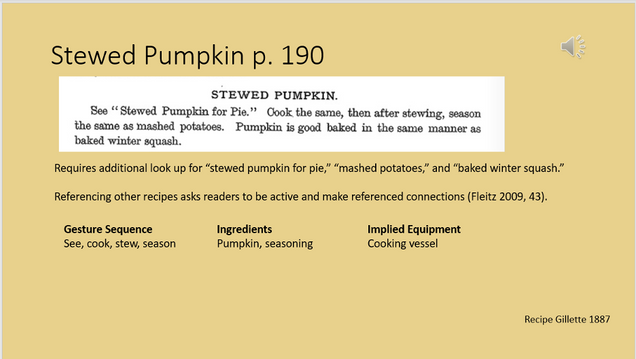

Pumpkins are a fruit native to North America (OED Online 2020; Terrell 2017). In looking for a historical recipe to recreate, I searched for pumpkin recipes since I had three sugar pumpkins that had been harvested from my garden this summer. It could be that recipes including pumpkin were not listed under the fruit, however, I perused over 20 cookbooks on the Feeding America website (https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa) looking for “pumpkin” in indices before finally finding some options. Most references were for pumpkin pie of which I am not a fan. Maria Parloa’s 1883 Miss Parloa's New Cookbook: A Guide to Marketing and Cooking held a recipe for pumpkin soup. This seemed promising, however the final instructions required three slices of stale bread. This would mean baking a loaf of bread and allowing some slices to stale. I did not have time for this. F.L. Gillette’s 1887 White House Cook Book: A Selection of Choice Recipes Original and Selected, During a Period of Forty Years' Practical Housekeeping had three pumpkin pie recipes, but also one for “stewed pumpkin” (Gillette 1887, 190). I had my recipe.

Mrs. Fanny Lemira Gillette published her cookbook in 1887 at 60 years old “at the urgent request of friends and relatives” (Michigan State University 2020). Dedicated to “the wives of our presidents” for no apparent reason other than perhaps marketing, she defines her audience as housekeepers and assures readers that she has “40 years of practical housekeeping” and the recipes have been vetted: “after trying and testing a recipe, and finding it invariably a success, and also one of the best of its kind, to copy it in a book… (Gillette 1887).” Her recipes are arranged in the “single-paragraph narrative structure of early print recipes” (Fleitz 2009, 59). Gesture sequences, or cooking instructions, are simple and authoritative. These are much harder to follow than the multimodal formats of today that separate out ingredients and measurements from the instruction. Her wording does not freely evoke the senses and does not readily encourage the reader to reconstruct herself as the coauthor. The layout has nominal margins and does not allow for the reader to add her own notes and share ownership of the recipes.

As soon as I begin the recipe, I am ordered to refer to other recipes and must look up “stewed pumpkin for pie,” “mashed potatoes,” and “baked winter squash.” Fleitz notes that referencing other recipes asks readers to be active and make referenced connections (Fleitz 2009, 43). I do not feel that I am making active, reference connections, however. I merely feel annoyance at having to scroll back and forth through the online scan of the book. Finally, I copy and paste each recipe I need and print them out onto one piece of paper. Now, I am actually ready to start.

Most recipes have scant cooking or baking times and no temperature, and narrative is used for quantities. There is little standardized measurement in the recipe I have picked, although the back of the book has a measures and weights section. The recipe for “Stewed Pumpkin for Pumpkin Pie” (Gillette 1887, 298) calls for a deep-colored pumpkin. Apparently, there was implied knowledge during that time about size and type of pumpkin. I am asked to pare the pumpkins. As I woefully assess my knife skills and the amount of pumpkin I am losing, I miss my vegetable peeler. Further instructions call for cutting into imprecise sizes such as “thick slices” and “small pieces.” I am instructed to use “very little water” in the pot where I put my prepared pumpkin pieces. When referencing the mashed potato recipe (Gillette 1887, 170) for seasoning, I am struck by the beginning of the first sentence “Take the quantity needed (of potatoes).” Surely, the seasoning amounts would differ if one were making mashed potatoes for four or for 10, but there is no mention of altering the seasoning amounts. Then there is the question of what counts as “seasoning.” Normally, I would think of spices. But it seems more effort to direct someone to a whole new recipe just for salt and pepper. Therefore, I reason that she is including butter and milk as seasoning as well. I need “butter the size of an egg,” a “good pinch of salt,” and “dots of pepper…as large as half a dime.” There is actually a measurement provided for the milk. My assumption is that whole milk would have been used, however, only having 1% milk, I measure out half a cup of that. I also use unsalted butters since it does not specify. There is a little ambiguity in the recipe, however I interpret the overall instruction as stopping the pie filling recipe prior to the colander step and then moving on to “season the same as mashed potatoes,” therefore, I decide that they should be served hot.

After preparing everything, I head outside to put my pot on a firepit. We only have an electric stovetop, so the firepit is my attempt at using a flame I need to tend to. A little more than an hour in, I decide to put a lid on the pot because the cooking is going very slowly. It simmers away for nearly an hour, until during one of my pot checks I am alarmed to see it severely discolored from soot. I scurry the pot inside and place it on my inauthentic electric stove pot. An hour later, I consider the pumpkin cooked per the instructions. From the start of prep and lighting the fire to having a final product, I have spent almost five hours. I was warned. The recipe mentions cooking the pumpkin “a long time, at least half a day” while “stirring often.” The expectation of the time was that the women will be at the stove all day cooking.

The baked pumpkin recipe (Gillette 1887, 188) turns out to be much easier and faster. I merely need to cut the pumpkin in half and scoop out the seeds. There is no paring or chopping. I cheat and put parchment paper between the baking sheet and the pumpkins. The only ambiguity is that I need to bake in a “moderately hot oven” for about an hour. I decided to cook at 400 degrees Fahrenheit. This recipe calls for no seasoning and ends up as plain mashed pumpkin.

The baked pumpkin recipe (Gillette 1887, 188) turns out to be much easier and faster. I merely need to cut the pumpkin in half and scoop out the seeds. There is no paring or chopping. I cheat and put parchment paper between the baking sheet and the pumpkins. The only ambiguity is that I need to bake in a “moderately hot oven” for about an hour. I decided to cook at 400 degrees Fahrenheit. This recipe calls for no seasoning and ends up as plain mashed pumpkin.

Both recipes, even the one that is seasoned, are bland for my family’s taste buds. I season the stewed pumpkin further, and to the baked pumpkin I add vanilla and sugar so that my family will eat them. The stewed pumpkin has less moisture and darker color, however both products are similar and were I to cook my own pumpkin again, I would surely use the baked method. I conclude my experiment appreciative of the material culture available to me and for the fact that I can choose to spend half a day cooking rather than being expected to do so,

Bibliography

Fleitz, Elizabeth J. 2009. The Multimodal Kitchen: Cookbooks as Women's Rhetorical Practice. Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate College, Bowling Green State University.

Gillette, F. L. 1887. White House Cook Book A Selection of Choice Recipes Original and Selected, during a period of Forty Years’ Practical Housekeeping. Chicago: R. S. Peale & Company.

Michigan State University Libraries. 2020. Gillette, F. L (Fanny Lemira), 1828-1926. Date of access November 12, 2020. https://d.lib.msu.edu/content/biographies?author_name=Gillette%2C+F.+L+%28Fanny+Lemira%29%2C+1828-1926

OED Online. 2020. "pumpkin, n.“ Oxford University Press. Date of access November 13, 2020. https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/view/Entry/154536?redirectedFrom=pumpkin

Parloa, Maria. 1883. Miss Parloa's New Cookbook: A Guide to Marketing and Cooking. New York: C.T. Dillingham.

Shanahan, Madeline. 2015. Manuscript Recipe Books as Archaeological Objects: Text and Food in the Early Modern World. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Terrell, Ellen. 2017. A Brief History of Pumpkin Pie in America. Library of Congress. Date of access November 12, 2020. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2017/11/a-brief-history-of-pumpkin-pie-in-america/

Food & The Senses: Conducting sensory labs during a pandemic

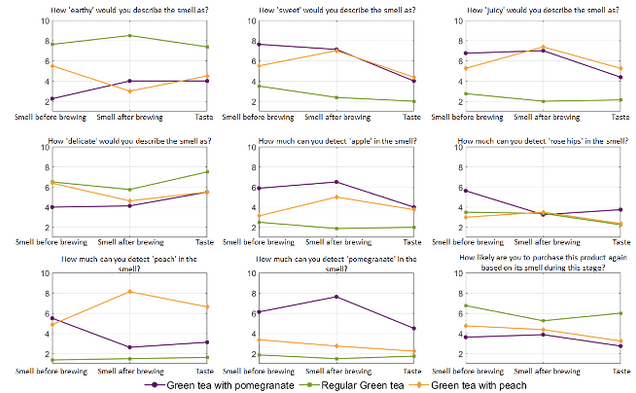

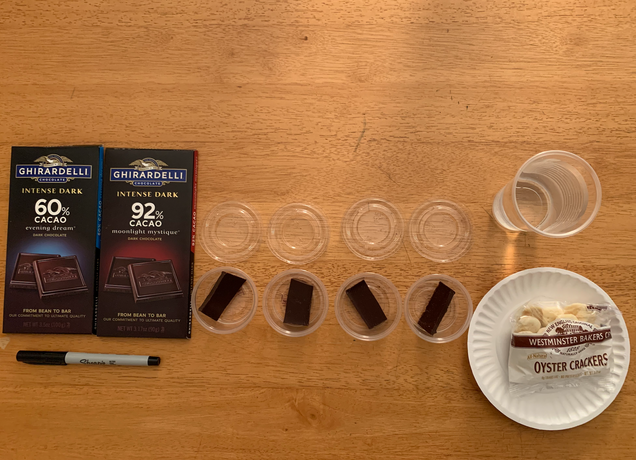

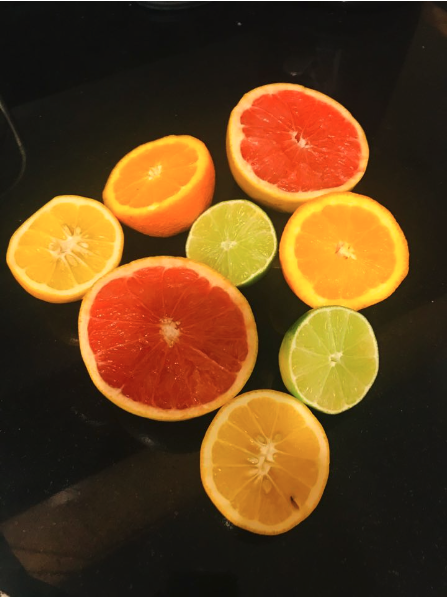

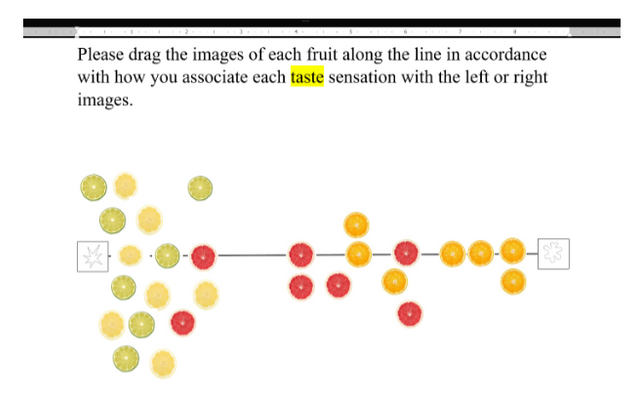

During the Fall 2020 semester, students in ML 715 Food and the Senses were tasked with conducting sensory labs during the Covid-19 pandemic. Equipped with a kit of basic supplies, students intelligently and creatively developed sensory experiments their classmates could take part in from their homes as we gathered virtually. Using qualitative and quantitative approaches, students successfully accounted for and took advantage of the in-home setting and virtual interaction mode in their research on sensory experience.

Sound Lab

Taste and Flavor Lab

Sight Lab

Touch Lab

Kate Zheng and Ester Martin

Can we touch and feel delicious without tasting? This lab explored touch as part of the multi-sensory experience of flavor and its connection to emotion. The feel of steak gives us information on how well cooked it is. How does the touch modality also influence our overall perception of flavor? How does touch influence enjoyment and disgust?

Cookbooks & History: A Beef-Steak Pie

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Christina Grace Setio.

Historical Recipe Recreation: 1840 Beefsteak Pie

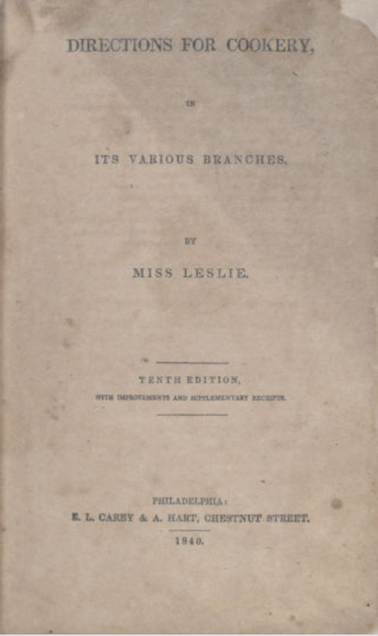

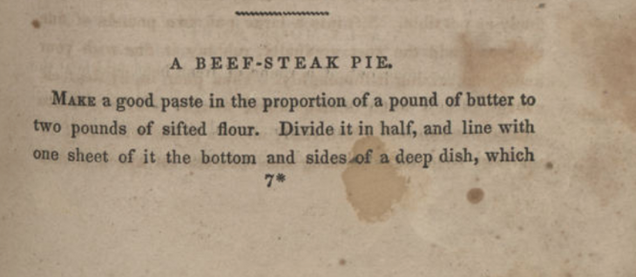

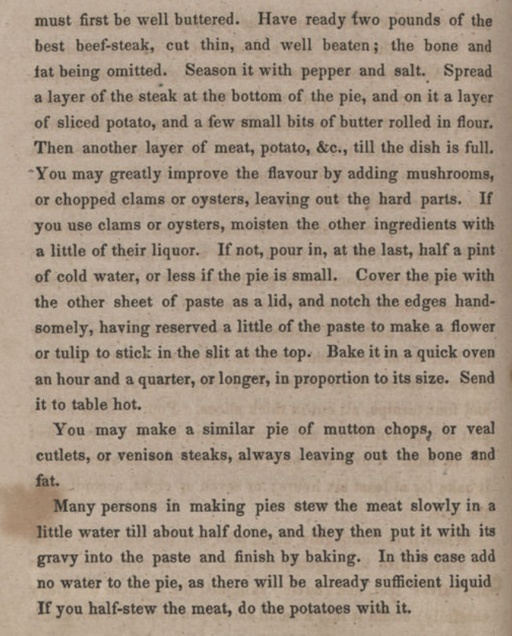

In the MET ML 630 Cookbooks and History class, we attempted to recreate a single or multiple historical recipes that are at least over a hundred years old. This project allowed for a hands-on historical analysis on the cooking production and consumption of that particular period of time. I chose an 1840 beefsteak pie recipe from a cookbook titled Direction for Cookery, in its Various Branches authored by Ms. Eliza Leslie. I accessed the digital version of the 10th edition copy where it was originally published in Philadelphia by E.L. Carey & A. Hart. Ms. Leslie was a decorated author of her time, and I find her writing style to be rather detailed and organized for an 1800 domestic cookbook. In the preface of her cookbook she has clearly stated her objective of providing American housewives with recipes adapted to the local produce and economy. She has also included measurement conversions and butchery diagram charts to aid even the most inexperienced cook.

I have always been intrigued by the built and flavor composition of old fashioned American pies. Although I wanted to choose something palatable enough for modern taste buds, I also wanted to be surprised by the outcome of this recipe recreation project. Because of the current pandemic, I had to keep in mind the accessibility of procuring the ingredients within potential recipes. When I found the beefsteak pie recipe (1840, 77), I was immediately intrigued by the idea of fusing the flavor of beef and oysters in a pie.

The first challenge arose in determining the exact ingredient variety that was available or commonly used in 1840 America. As an example, the recipe for making the pie crust simply states “Make a good paste [pastry] in the proportion of a pound of butter to two pounds of sifted flour” (1840, 77). For a modern housewife, one might have endless choice of what that flour may be: bleached pastry flour, whole wheat flour, all-purpose flour, or even gluten-free flour. However in 1840, half of those flour may not even have existed or been available to the general public. Historically, whole wheat kernels must be ground using a millstone to obtain wheat flour (Campbell 2007). Since the bran, endosperm, and germ of the kernels are all ground up together, it would most resemble what we today know as whole wheat flour. Refined white flour was only available after the invention of roller mills in 1870s, thus for this recipe refined flours will not give us an accurate flavor and character. Measurement could equally be a common issue when attempting an older recipe, as old cookbooks may use different terms and also standardization was common only after the 1900s. This savory beefsteak recipe was no different, I had no exact amount to follow with some of the ingredients within the pie. Finally the materials available in an 1840 kitchen vary greatly to what we find in a 2020 kitchen. It was extremely challenging to escape the convenience of relying on industrialized produce like plastic cling wrap, a meat pounder, or a pastry brush.

The first challenge arose in determining the exact ingredient variety that was available or commonly used in 1840 America. As an example, the recipe for making the pie crust simply states “Make a good paste [pastry] in the proportion of a pound of butter to two pounds of sifted flour” (1840, 77). For a modern housewife, one might have endless choice of what that flour may be: bleached pastry flour, whole wheat flour, all-purpose flour, or even gluten-free flour. However in 1840, half of those flour may not even have existed or been available to the general public. Historically, whole wheat kernels must be ground using a millstone to obtain wheat flour (Campbell 2007). Since the bran, endosperm, and germ of the kernels are all ground up together, it would most resemble what we today know as whole wheat flour. Refined white flour was only available after the invention of roller mills in 1870s, thus for this recipe refined flours will not give us an accurate flavor and character. Measurement could equally be a common issue when attempting an older recipe, as old cookbooks may use different terms and also standardization was common only after the 1900s. This savory beefsteak recipe was no different, I had no exact amount to follow with some of the ingredients within the pie. Finally the materials available in an 1840 kitchen vary greatly to what we find in a 2020 kitchen. It was extremely challenging to escape the convenience of relying on industrialized produce like plastic cling wrap, a meat pounder, or a pastry brush.

The beefsteak pie turned out better than expected; although not visually as appealing as I had hoped, the oysters gave it more character. The idea of recreating a historical recipe seems intimidating at first, however it proves to be an exciting way to learn about the past. Not only are we are able to visualize how food may have been produced, engaging all of our senses allows for a fully submersive experience. Next project, Mrs. Seely’s Colonial Codfish Pie!

The beefsteak pie turned out better than expected; although not visually as appealing as I had hoped, the oysters gave it more character. The idea of recreating a historical recipe seems intimidating at first, however it proves to be an exciting way to learn about the past. Not only are we are able to visualize how food may have been produced, engaging all of our senses allows for a fully submersive experience. Next project, Mrs. Seely’s Colonial Codfish Pie!

Bibliography

Campbell, Grant M. 2007. “Roller Milling of Wheat.” Handbook of Powder Technology 12: 383-419. Date of access, November 10, 2020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167378507120108

Leslie, Eliza. 1840. Direction for Cookery, in its Various Branches. 10th ed. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart. Date of access, November 5, 2020. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/20#page/82/mode/2up

Cookbooks & History: Dutch Chocolate Cake

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Adrian Bresler.

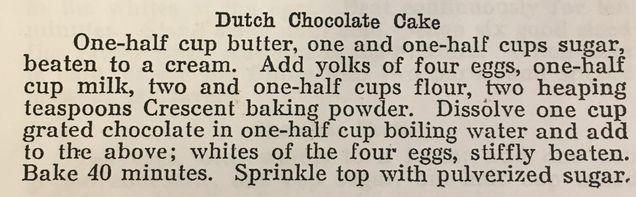

We were asked to recreate an historical recipe that was over 100 years old for our Cookbooks and History class assignment; I soon discovered that the alternatives were endless. But the Dutch Chocolate Cake recipe in “The Neighborhood Cookbook” seemed to be the right choice for me. With over 42 cake recipes (14 were variations of chocolate cake), this community cookbook, compiled and issued by The Council of Jewish Women of Portland Oregon in 1914 to fundraise for their organization, was filled with recipes written by women whose concise directions communicated to me their expertise and confidence. How could I go wrong with my choice? Their first edition, printed in 1912, sold out in ten months. And since my last attempt at baking a chocolate cake ended in a lumpy mess, now was the opportunity for redemption using a recipe written long ago by women who really knew how to cook.

We were asked to recreate an historical recipe that was over 100 years old for our Cookbooks and History class assignment; I soon discovered that the alternatives were endless. But the Dutch Chocolate Cake recipe in “The Neighborhood Cookbook” seemed to be the right choice for me. With over 42 cake recipes (14 were variations of chocolate cake), this community cookbook, compiled and issued by The Council of Jewish Women of Portland Oregon in 1914 to fundraise for their organization, was filled with recipes written by women whose concise directions communicated to me their expertise and confidence. How could I go wrong with my choice? Their first edition, printed in 1912, sold out in ten months. And since my last attempt at baking a chocolate cake ended in a lumpy mess, now was the opportunity for redemption using a recipe written long ago by women who really knew how to cook.

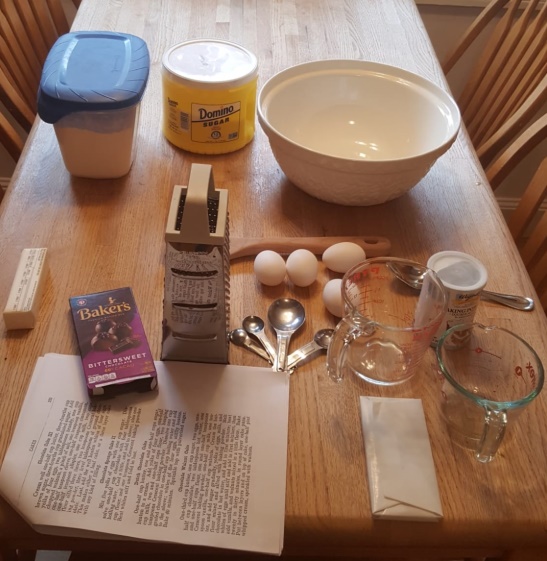

The Cake section of the cookbook began with a set of general instructions. Here, the editor reminded readers to measure carefully, to use an earthen dish and a wooden spoon, to never remove a cake from the oven until it is done, and to use a clean broom straw to test the cake. (Lacking a clean broom straw, I substituted a wooden toothpick).

With the introduction over, I was ready to begin to bake. The recipe I chose consisted of a mere five sentences from start to finish, including a list of ingredients embedded in the short paragraph. The brevity of the directions gave the appearance of simplicity, a notion that was quickly dispelled when the baking began.

Creaming the butter and sugar with a wooden spoon, rather than using my KitchenAid mixer, took more time and muscle energy but it worked. No problem so far. The addition of egg yolks, milk, flour, and baking powder was fairly simple, too. Interrupting the action to fill the tea kettle to boil water, instead of zapping the water in the microwave, was a distraction but not really a problem. However, grating the Baker’s chocolate squares triggered an unexpected complication. The friction from the scraping caused the chocolate shavings to go airborne when the particles became statically charged. Chocolate bits flew through the air and landed everywhere including into the bowl of egg whites, which according to sentence number three, still needed to be ‘stiffly beaten’. The sight of chocolate flecks floating in the egg whites caused me some grief but just then the tea kettle whistled, announcing that it was time to melt the remaining chocolate with the boiling water. Here, the brief instructions gave me only vague guidance; I hesitated a moment before pouring the boiling water into the chocolate, rather than adding the chocolate to the water. It melted. So far, so good.

Although electric hand mixers were invented in the late 1800s, they did not become available for home use until the 1920s. To beat the (already contaminated with chocolate shavings) egg whites into a stiff froth, I turned to my mother’s old manual egg beater. Compared to the way my grandmother whipped egg whites-- with a fork-- this seemed fairly easy. As the recipe gave no further instruction, I simply folded the egg whites, now a bowl of white fluff in spite of the floating chocolate, into the rest of the batter.

With no directions regarding the type or size of the baking pan, I selected an angel food cake pan that seemed large enough to accommodate the batter. I buttered the pan to prevent sticking since cooking spray was not available to the public until the 1960s.

Remembering to return to the Cake introduction for guidance regarding oven temperature, I found that Layer cake required a ‘quick fire’, Sponge cake a ‘slow fire’, and Loaf cake with butter a ‘moderate fire’. My electric oven generates no fire. I assumed I was making a loaf cake but I was mistaken. Setting the oven at 325 degrees, I followed the fourth sentence of the directions (“…bake 40 minutes…”).

Luckily for me the fifth and last line of the instructions told the readers to sprinkle pulverized sugar on top of the cake as a finishing touch. Using confectioners’ sugar, I covered up the burned spots. The cake was a bit dry and crumbly as a result of overbaking. And the chocolate flavor was muted—perhaps too many chocolate particles flew up into the air instead of into the cake.

But at least it did not turn out to be another lumpy mess. And my family liked it. I’ve made progress.

Therefore, I owe a debt of gratitude to the now defunct Council of Jewish Women of Portland. More importantly, their cookbook helped fund the organization’s mission, which was to help new immigrants, promote women’s suffrage, provide vocational classes, and support other social issues.

Works Cited:

Conagra. 2020. “When you pick up a pan, spray it with PAM.” Pam: Our Story. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://pam.conagrafoods.ca/our-story/

Council of Jewish Women of Portland, OR. 1914. The Neighborhood Cookbook. Portland, OR: Bushong & Co. https://n2t.net/ark:/85335/m5dh3z

Kitchen Tool Reviews. 2016. “What you didn’t know about your hand mixer.” Kitchen Tool Reviews. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://www.kitchentoolreviews.com/2016/08/01/what-you-didnt-know-about-your-hand-mixer/.

Moon, Deborah. 2015. “Portland NCJW Dissolves, but Legacy Lives on.” Oregon Jewish Life. May 27, 2015. https://orjewishlife.com/portland-ncjw-dissolves-but-legacy-lives-on/

Scholerman, Antonia. 2018. “Portland’s Neighborhood House and The National Council of Jewish Women.” The Oregon Women’s History Consortium. http://www.oregonwomenshistory.org/portlands-neighborhood-house-and-the-national-council-of-jewish-women-by-antonia-scholerman/

Cookbooks & History: Foods of the Foreign-Born, Eggs

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to bring in to class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the second essay in this series, written by Marie-Louise Friedland.

Foods of the Foreign-Born But Make It Bland

When I saw that we had to recreate a recipe from pre-1930s, my brain was swimming. I could not decide on whether I should focus on an ingredient, a time period, a cooking technique, or a specific cookbook. It was after a topic of discussion for the class that I had my epiphany. I was drawn to what recipes represent, specifically what the subtext is behind prescriptive cookbooks and the recipes within. The cookbook Foods of the Foreign Born by Bertha M. Wood was the cookbook that I was determined to cook a recipe from because I wanted to understand the mindset behind the cookbook.

As stated before, the cookbook falls under the prescriptive type of cookbook in that it acts as a prescription for how to cook to take care of one’s health. In Foods of the Foreign Born, Wood takes it to another level by recommending how to change the foods of different groups of immigrants to a “healthier” version. What I read in this is that the Americanization of immigrant cuisine is the proper way to assimilate into American society and not only will it better one’s health, but it will better one’s chances of becoming more American. As I dive more into the history of American foodways, I’ve slowly become less and less shocked by how desperately Americans wanted to “other” immigrants, but this cookbook stopped me in my tracks.

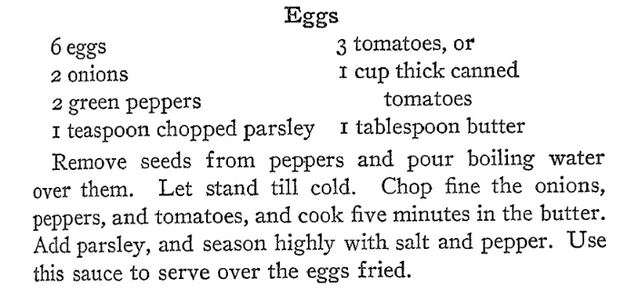

I decided to recreate a recipe called “Eggs” from the Mexican section of the cookbook. I made this decision because growing up in San Antonio, Texas I was in constant contact with Americanized Mexican food and authentic Mexican food. Those two styles were in perpetual struggle for authenticity but offered a great view of the immigrant cuisine’s treatment in the United States. Just by looking over the recipe, two things immediately jumped out at me. First, the ingredients seemed relatively bland. Second, there was no mention of any cooking utensils or materials.

I decided to recreate a recipe called “Eggs” from the Mexican section of the cookbook. I made this decision because growing up in San Antonio, Texas I was in constant contact with Americanized Mexican food and authentic Mexican food. Those two styles were in perpetual struggle for authenticity but offered a great view of the immigrant cuisine’s treatment in the United States. Just by looking over the recipe, two things immediately jumped out at me. First, the ingredients seemed relatively bland. Second, there was no mention of any cooking utensils or materials.

I gathered the ingredients at the grocery store and then started to think through the materials. I knew that the cookbook’s audience was a medical staff or a large hospital because the cookbook discusses diseases that would need medical attention if they went untreated. That fact allowed me to pick very sturdy and affordable cooking materials that would most likely be used by a staff. I decided to use all wooden utensils, a cast iron pan and ceramic bowl and serving dish. Once that was sorted the next mystery I had to solve was how to cook everything. I decided on doing it over fire to mimic a gas stove which is most likely what these medical establishments had for cooking. I used our grill that had a moveable grate so I could control the heat level under the cast iron. The recipe itself was pretty simple to recreate because everything went into the pot and as cooked down and then poured on top of six fried eggs.

I am not a master chef so it was quite easy for me to stay true to the recipe. There is always a gut instinct to stray from the recipe to make it edible, but I really wanted to get into the frame of mind of the author. I thought it was important to cook the recipe the way Wood prescribed it to be cooked because I wanted to taste it the way she intended it. This would allow me to fully understand the Americanization of a Mexican dish that was supposedly healthier than the original dish. There were a few improvisations I made that impacted the end result. I cooked it 5 minutes longer than it said to do so because I don’t think I chopped the vegetables fine enough to have them quickly cook down into a sauce. I also added a pinch more parsley in the hopes that it would add a little bit more flavor. There were also no instructions on how to fry the six eggs so I did fry them in about a tablespoon of butter in the same cast iron pan that I used to cook the vegetables in.

Once the cooking was done, I had my husband and stepfather try it and both said it was bland. My husband who is a chef and grew up in Mexico was not impressed. My stepfather added lots of hot sauce and had two helpings of it so it’s safe to say that he enjoyed it after he added his own flavor to it. The fact that the result was a plate of bland, sauteed vegetables over fried eggs was not a surprise to me considering that the recipe was intended to be healthy and help reverse some diet-related illnesses. My gut was telling me to add flavor or treat the recipe like migas to make it more enjoyable, but I knew that the whole point was to Americanize an immigrant dish under the guise of making it healthier.

The recreation of this historical recipe provided me with an incredible insight into the style of prescriptive cookbooks. The distaste for immigrant cuisine is evident in Foods of the Foreign Born although it uses the concept of healthy cuisine as a remedy for diet-related ailments to hide behind. Next time I am going to make migas.

Bibliography

Wood, Bertha M., Foods of the Foreign-Born: In Relation to Health. 1922.

Boston, MA: Whitcomb & Barrows.

Recipe appears on page 11.

Cookbooks & History: 1836 Rich Rice Pudding

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the first essay in this series, written by Sarit Sadras Rubinstein.

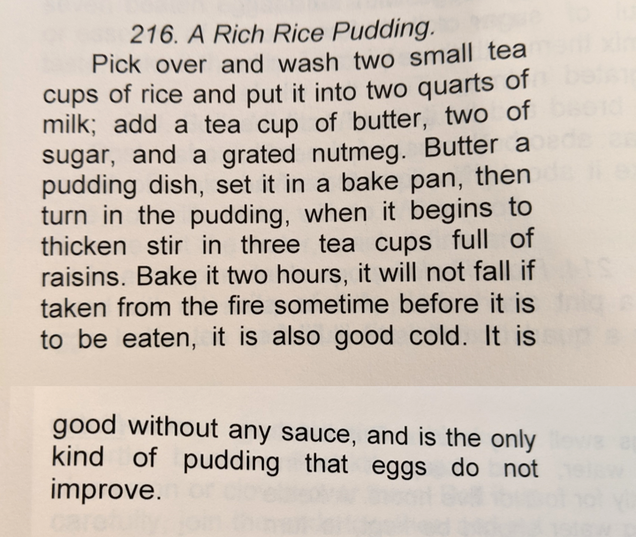

1836 Rich Rice Pudding

There is nothing like a comforting rice pudding. Whether served warm or cold, the few simple ingredients and the flavors they yield make it a great dessert. And with the fact that it is also filling, you get a winning dish.

It was raining outside when I searched for a recipe to recreate for this project for the Cookbooks and History class. Since I already had a copy of the book The New England Cookbook (1836), I decided to look through the recipes and see if I liked one. Even though it may have been tempting to try a recipe such as the “pressed head” (cooking a pig’s head), I thought it would be best for everyone's sake if I chose a less exotic recipe. So when I suddenly noticed the recipe for “a rich rice pudding,” I knew this was it. It was a perfect match for the day’s weather.

Even though rice pudding is supposedly not too complicated to make, there are so many versions of it, meaning each recipe can yield very different results -- starting with the cooking process, the texture, sweetness, and even the overall look of the dish. I was curious to see how they made it during the 1800s and what it would taste like.

The recipe was quite short in length, but once reading it there were a few questions that popped up for me even before making anything. Some of them were regarding the ingredients. For example, what kind of rice were they using back in the 1800s? There are so many kinds of rice I can choose from (some are long-grain, medium-grain, white, brown). I decided to go with medium-grain rice since this is the one I usually use for rice pudding.

Some questions were about measuring. For example, there was no specific amount for how much nutmeg to add. Another example is the measuring tools and dishes that were used. What was a teacup measurement? What was a pudding dish? Unfortunately, I had no idea what those were back then and what are their equivalents in today’s time.

The biggest question, however, was about the cooking and the baking process. There was not enough information given in the recipe about the first step of the cooking. I just assumed they would like me to cook the pudding on the stove (or the fire back in the 1800s) until it thickened. Then, there was no information at all about the baking process, besides the overall baking time of two hours. There was not even a general idea of what heat (high or low) to use, which I had to guess again, and decided on 350F.

Once I figured out the ingredients, the amounts, and answered some of the questions (by making educated guesses), I could start making the recipe. The first few steps were not that complicated. I simply added the ingredients except for the raisins to the saucepan. But then, the recipe stated that the mixture needed to thicken. I assumed they meant this should happen while it was on the stove, so this is what I did. I kept it on medium heat until the rice was partly cooked. At this point, it felt like the pudding had slightly thickened. It is then when I added the raisins as the recipe stated, transferred the pudding to a buttered dish, and put it in the oven. The recipe is also quite large, so I ended up with two dishes of rice pudding.

As mentioned above, no instructions were given about the baking besides the total baking time. However, whereas the recipe said two hours at 350F, it took only 50 minutes until the pudding was completely cooked. Once done, the pudding was golden and brown on top, and all the liquid (milk) was absorbed in the rice. It smelled really good. The rice was soft, and the pudding was very sweet, even too sweet to my family’s taste (and we love sugar in our house). That said, I would say this recipe overall was a success. It might scream for adding cinnamon and vanilla (and cutting off some sugar), but I was quite impressed by how good it was, considering it is an 1836 recipe.

As previously mentioned, the recipe yielded two dishes of rice pudding, and also had some little extra in the saucepan. I decided to experiment with the leftovers in the saucepan, and while the two dishes of pudding were baking in the oven, I continued to cook the leftovers on the stove, as this is my regular cooking method for rice pudding. The texture became more like a porridge (and not solid, as in the baked version), and again very sweet. Once again, a successful result.

Overall this was a very interesting assignment. Going through the procedure of actually cooking the recipe teaches you a lot about the process of cooking, the available ingredients, and kitchen tools, and it raises questions that might have been missed by just reading the recipe. Rice pudding was always a favorite of mine. It always makes me smile and brings me back home, to my mom’s recipe, and my grandma’s recipe. Even though I would declare the 1836 recipe as a successful one, I will stick with my mom’s recipe for rice pudding. But whatever recipe you may choose, I guess one cannot really go wrong with a mixture of butter, milk, and sugar, right?

Bibliography

Kellscraft Studio. 2011. The New England Cook Book: A Young Housekeeper’s Guide. Originally published in 1836. Canaan, Maine.

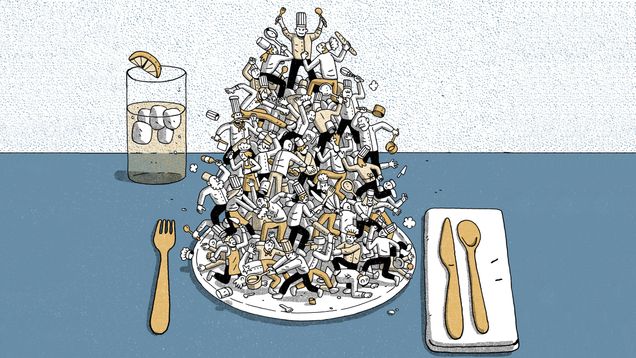

Course Spotlight: Food Waste

Steven Finn will be teaching MET ML626 A1, Addressing Food Waste for a Sustainable Food System, during the Spring 2021 semester. Steven Finn is Vice President for Food Waste Prevention at Leanpath, Inc. and Co-founder and Managing Director for ResponsEcology, Inc.

Food waste is a hot topic but not a new one. Some wasted food is the sign of a healthy system—if there were exactly enough calories produced to meet each of our needs, there would be mass starvation, riots, and hoarding as we all scrambled to get our share. But by some estimates, food loss and waste account for nearly 40% of the food produced. How much wasted food is too much? At the same time this food is wasted, food insecurity is everywhere, even on BU’s campus. Is all wasted food “trash?” Need it be? Why is food wasted and where along the supply chain is it wasted? What are the ethics of donating surplus food/waste/trash of those who have too much to those who don’t have enough? This hybrid course explores the history, culture, rhetoric, and practicalities of wasted food, from farm, through fork, to gut (is overeating a form of food waste? What about wasting micronutrients by converting them to ultraprocessed foods?). Each week includes readings, discussion, application activity, and a guest lecture from a food system practitioner. Students will work together to develop practical solutions in a final project.

This 4-credit course will take place on Thursdays from 6:00 to 8:45 PM. The course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Please contact gastrmla@bu.edu for more information.

Course Spotlight: Sociology of Taste

Are you still looking to complete your Spring 2021 schedule? Connor Fitzmaurice will be teaching Sociology of Taste (MET ML 716 A1) on Thursday evenings.

Taste has an undeniable personal immediacy: producing visceral feelings ranging from delight to disgust. As a result, in our everyday lives we tend to think about taste as purely a matter of individual preference. However, for sociologists, our tastes are not only socially meaningful, they are also socially determined, organized, and constructed. This course will introduce students to the variety of questions sociologists have asked about taste. What is a need? Where do preferences come from? What social functions might our tastes serve? Major theoretical perspectives for answering these questions will be considered, examining the influence of societal institutions, status seeking behaviors, internalized dispositions, and systems of meaning on not only what we enjoy–but what we find most revolting.

If this course sounds interesting to you, please find registration information below.

MET ML 716 A1, Sociology of Taste, will meet on Thursday evenings from 6 to 8:45 PM, beginning on January 28th. Registration information can be found here.