Cookbooks & History: Stewed Pumpkin

Students in Cookbooks and History (MET ML 630), directed by Dr. Karen Metheny, researched and recreated a historical recipe to share with the class. They were instructed to note the challenges they faced, as well as define why they selected their recipe and why it appealed to them. Here is the next essay in this series, written by Kris Kaktins.

Pumpkins are a fruit native to North America (OED Online 2020; Terrell 2017). In looking for a historical recipe to recreate, I searched for pumpkin recipes since I had three sugar pumpkins that had been harvested from my garden this summer. It could be that recipes including pumpkin were not listed under the fruit, however, I perused over 20 cookbooks on the Feeding America website (https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa) looking for “pumpkin” in indices before finally finding some options. Most references were for pumpkin pie of which I am not a fan. Maria Parloa’s 1883 Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook: A Guide to Marketing and Cooking held a recipe for pumpkin soup. This seemed promising, however the final instructions required three slices of stale bread. This would mean baking a loaf of bread and allowing some slices to stale. I did not have time for this. F.L. Gillette’s 1887 White House Cook Book: A Selection of Choice Recipes Original and Selected, During a Period of Forty Years’ Practical Housekeeping had three pumpkin pie recipes, but also one for “stewed pumpkin” (Gillette 1887, 190). I had my recipe.

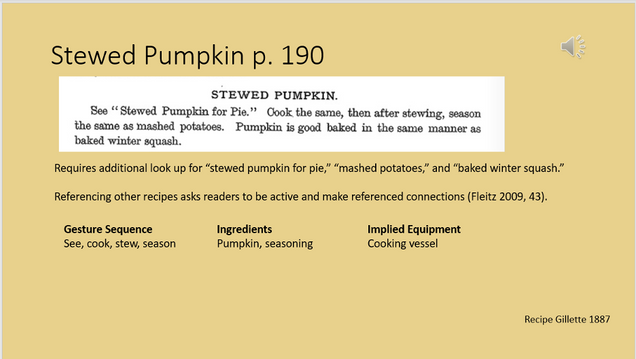

Mrs. Fanny Lemira Gillette published her cookbook in 1887 at 60 years old “at the urgent request of friends and relatives” (Michigan State University 2020). Dedicated to “the wives of our presidents” for no apparent reason other than perhaps marketing, she defines her audience as housekeepers and assures readers that she has “40 years of practical housekeeping” and the recipes have been vetted: “after trying and testing a recipe, and finding it invariably a success, and also one of the best of its kind, to copy it in a book… (Gillette 1887).” Her recipes are arranged in the “single-paragraph narrative structure of early print recipes” (Fleitz 2009, 59). Gesture sequences, or cooking instructions, are simple and authoritative. These are much harder to follow than the multimodal formats of today that separate out ingredients and measurements from the instruction. Her wording does not freely evoke the senses and does not readily encourage the reader to reconstruct herself as the coauthor. The layout has nominal margins and does not allow for the reader to add her own notes and share ownership of the recipes.

As soon as I begin the recipe, I am ordered to refer to other recipes and must look up “stewed pumpkin for pie,” “mashed potatoes,” and “baked winter squash.” Fleitz notes that referencing other recipes asks readers to be active and make referenced connections (Fleitz 2009, 43). I do not feel that I am making active, reference connections, however. I merely feel annoyance at having to scroll back and forth through the online scan of the book. Finally, I copy and paste each recipe I need and print them out onto one piece of paper. Now, I am actually ready to start.

Most recipes have scant cooking or baking times and no temperature, and narrative is used for quantities. There is little standardized measurement in the recipe I have picked, although the back of the book has a measures and weights section. The recipe for “Stewed Pumpkin for Pumpkin Pie” (Gillette 1887, 298) calls for a deep-colored pumpkin. Apparently, there was implied knowledge during that time about size and type of pumpkin. I am asked to pare the pumpkins. As I woefully assess my knife skills and the amount of pumpkin I am losing, I miss my vegetable peeler. Further instructions call for cutting into imprecise sizes such as “thick slices” and “small pieces.” I am instructed to use “very little water” in the pot where I put my prepared pumpkin pieces. When referencing the mashed potato recipe (Gillette 1887, 170) for seasoning, I am struck by the beginning of the first sentence “Take the quantity needed (of potatoes).” Surely, the seasoning amounts would differ if one were making mashed potatoes for four or for 10, but there is no mention of altering the seasoning amounts. Then there is the question of what counts as “seasoning.” Normally, I would think of spices. But it seems more effort to direct someone to a whole new recipe just for salt and pepper. Therefore, I reason that she is including butter and milk as seasoning as well. I need “butter the size of an egg,” a “good pinch of salt,” and “dots of pepper…as large as half a dime.” There is actually a measurement provided for the milk. My assumption is that whole milk would have been used, however, only having 1% milk, I measure out half a cup of that. I also use unsalted butters since it does not specify. There is a little ambiguity in the recipe, however I interpret the overall instruction as stopping the pie filling recipe prior to the colander step and then moving on to “season the same as mashed potatoes,” therefore, I decide that they should be served hot.

After preparing everything, I head outside to put my pot on a firepit. We only have an electric stovetop, so the firepit is my attempt at using a flame I need to tend to. A little more than an hour in, I decide to put a lid on the pot because the cooking is going very slowly. It simmers away for nearly an hour, until during one of my pot checks I am alarmed to see it severely discolored from soot. I scurry the pot inside and place it on my inauthentic electric stove pot. An hour later, I consider the pumpkin cooked per the instructions. From the start of prep and lighting the fire to having a final product, I have spent almost five hours. I was warned. The recipe mentions cooking the pumpkin “a long time, at least half a day” while “stirring often.” The expectation of the time was that the women will be at the stove all day cooking.

The baked pumpkin recipe (Gillette 1887, 188) turns out to be much easier and faster. I merely need to cut the pumpkin in half and scoop out the seeds. There is no paring or chopping. I cheat and put parchment paper between the baking sheet and the pumpkins. The only ambiguity is that I need to bake in a “moderately hot oven” for about an hour. I decided to cook at 400 degrees Fahrenheit. This recipe calls for no seasoning and ends up as plain mashed pumpkin.

The baked pumpkin recipe (Gillette 1887, 188) turns out to be much easier and faster. I merely need to cut the pumpkin in half and scoop out the seeds. There is no paring or chopping. I cheat and put parchment paper between the baking sheet and the pumpkins. The only ambiguity is that I need to bake in a “moderately hot oven” for about an hour. I decided to cook at 400 degrees Fahrenheit. This recipe calls for no seasoning and ends up as plain mashed pumpkin.

Both recipes, even the one that is seasoned, are bland for my family’s taste buds. I season the stewed pumpkin further, and to the baked pumpkin I add vanilla and sugar so that my family will eat them. The stewed pumpkin has less moisture and darker color, however both products are similar and were I to cook my own pumpkin again, I would surely use the baked method. I conclude my experiment appreciative of the material culture available to me and for the fact that I can choose to spend half a day cooking rather than being expected to do so,

Bibliography

Fleitz, Elizabeth J. 2009. The Multimodal Kitchen: Cookbooks as Women’s Rhetorical Practice. Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate College, Bowling Green State University.

Gillette, F. L. 1887. White House Cook Book A Selection of Choice Recipes Original and Selected, during a period of Forty Years’ Practical Housekeeping. Chicago: R. S. Peale & Company.

Michigan State University Libraries. 2020. Gillette, F. L (Fanny Lemira), 1828-1926. Date of access November 12, 2020. https://d.lib.msu.edu/content/biographies?author_name=Gillette%2C+F.+L+%28Fanny+Lemira%29%2C+1828-1926

OED Online. 2020. “pumpkin, n.“ Oxford University Press. Date of access November 13, 2020. https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/view/Entry/154536?redirectedFrom=pumpkin

Parloa, Maria. 1883. Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook: A Guide to Marketing and Cooking. New York: C.T. Dillingham.

Shanahan, Madeline. 2015. Manuscript Recipe Books as Archaeological Objects: Text and Food in the Early Modern World. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Terrell, Ellen. 2017. A Brief History of Pumpkin Pie in America. Library of Congress. Date of access November 12, 2020. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2017/11/a-brief-history-of-pumpkin-pie-in-america/