No Two Markets are the Same

Students Karen Metheny's summer course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts. This example of participant observation comes from Gastronomy student Kate Cherven.

On Saturday, June 1st, I went to the Boston Public Market and Haymarket to conduct participant observation for two hours from 8:30 am until 10:30 am. These two locations are called “markets,” which are understood to be public spaces where people gather to sell and purchase goods, such as foodstuffs and other commodities. Yet, even though these two locations are called markets, their characteristics are very different from one another.

The Boston Public Market is an indoor food hall that provides specific branded stalls for different vendors to sell their products. Most of the products for sale in the Boston Public Market are: food prepared to eat right away, prepared food that can be taken to another location to be eaten, food to take home and prepare, as well as non-edible goods such as soap and yarn. The Boston Public Market is open year round and is available everyday from 7am until 8pm (Boston Public Market 2019). Haymarket is an outdoor market that is year round and is open Fridays and Saturdays from around 4am until 7pm (Market Tips 2019). The Haymarket stalls sell products that are mostly vegetables and produce, with some stalls selling seafood.

Thinking on Ray Oldenburg’s term “third place,” I wonder if Haymarket or the Boston Public Market can be considered “third places” (Lin 2012, 120). Oldenburg defines “third places” as locations that are “free or inexpensive, usually having food and drink, and being highly accessible for mixing and mingling in a comfortable atmosphere” (Lin 2012, 120). Haymarket fits this description in a few ways, because it is a space that is inexpensive and it is accessible for mixing and mingling, yet food and drink are not available on site for people to sit and share while socializing.

By comparing the social supportive resources outlined in Lin’s 2012 article, "Starbucks as the Third Place: Glimpses into Taiwan's Consumer Culture and Lifestyles," I claim that customers at Haymarket don’t receive these resources, therefore I don’t believe Haymarket would be considered a “third place” by Oldenburg’s description (Lin 2012, 120). Haymarket does not possess a pleasing and decorative space, a clean space, comfortable seating, nor cozy surroundings (2012, 122). Haymarket does possess a reputation as a historical and cultural site in Boston and is a tourist attraction (Experience 2019).

Yet, while Haymarket provides a space for social interactions, it does not create a space for people to sit and gather and build communal social relations. Anderson states in the book, Everyone Eats: Understanding Food and Culture, Second Edition, “People almost always eat as a social act” (2014, 138); therefore if Haymarket doesn’t provide a space for this social act, I don’t consider it a “third place.”

Boston Public Market seems to be a better match for “third place.” The Boston Public Market has a pleasing and decorative space, is clean, provides comfortable seating, enjoyable music, a prestigious reputation, and provides high quality products (Boston Public Market 2019). While I walked around, I noticed that the Boston Public Market has numerous gathering locations made from large communal tables, or standing tables where people are able to gather and consume their purchased products. Yet, the Boston Public Market doesn’t seem to fit the “third place” definition of being either free or inexpensive, with the majority of their products for sale being more than $5 USD. Yet, it is possible for a person to come into the Boston Public Market to sit and not buy anything, therefore it can be used as a free gathering space.

I found it interesting to observe two food spaces in Boston that are called “markets” yet are drastically different from one another. Haymarket is an outdoor space that provides raw food products for individuals to purchase and take home with them to prepare, while the Boston Public Market is an indoor space that provides mainly prepared meals for people to sit and enjoy within the space or take with them to other locations. When using Ray Oldenburg’s concept of a “third place,” I was able to understand how customers receive social supportive resources from food spaces and concluded that while the Boston Public Market would be considered a “third place,” I believe Haymarket would not. I’m not sure if there is a “fourth place” in which Haymarket would fit, but I find it interesting to conclude that even though these two food spaces are called “markets,” their social supportive resources are drastically different from one another.

Work Cited:

Anderson, E. N. 2014. Everyone Eats: Understanding Food and Culture, Second Edition. New York University Press, New York.

Boston Public Market. n.d.. Retrieved June 5, 2019. https://bostonpublicmarket.org/

Experience. n.d.. Retrieved June 6, 2019. http://www.haymarketboston.org/market-tips

Lin, En-Ying. 2012. Starbucks as the Third Place: Glimpses into Taiwan's Consumer Culture and Lifestyles. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 24 (1-2), 119-128.

Market Tips. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2019. http://www.haymarketboston.org/market-tips

Food Mapping at H-Mart

Students Karen Metheny's summer course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts. This food mapping example comes from Gastronomy student Jie Liu.

Food mapping is a tool that can be used to figure out where people buy and eat food, what their preferences are, and how they behave in a food system. In this entry on food mapping, you will clearly see how people move through the space and what connections people create through food. I will connect my observations to three different aspects of food mapping to see what we can learn from this practice.

I chose H Mart, a popular Asian supermarket chain in America, as the site of my mapping observation. This specific supermarket has a small food court with three vendors: Paris Baguette Café, Go Go Curry, and Sapporo Ramen. It is a very good place to have a meal and a cup of coffee, and then buy some groceries, all at one stop. Besides the supermarket, Paris Baguette Café is another reason that I come here very frequently. This international and premium bakery-café brand was founded in 1998. It serves a variety of treats—not only breads, pastries, and cakes, but chef-inspired sandwiches and salads, and different kinds of drinks. I chose to observe the food court, especially paying attention to Paris Baguette Café. I was hoping to get more information about how people interact within this area, and in relation to the environment.

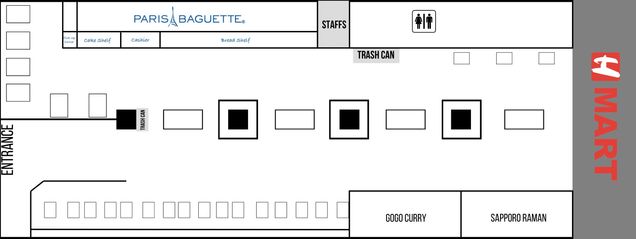

H Mart is located at 581 Massachusetts Avenue and is just steps from the Central Red line which is a very easy destination for costumers. Beside the large logo of H Mart in front of the main entrance, people also can see the signs for three vendors, but especially Paris Baguette Café. The Cambridge H Mart food court area is clean, sleek, and well organized. The appealing inner decoration, the clean environment, and the exotic food extend the role of H Mart beyond its function as a supermarket to a destination for dining and a place to relax. There is a modern and organized bakery-café store you can see first when you enter from the main gate. As you can see from the map (Figure 1), in the upper left corner, there are six tables with leather sofas belong to the café. All six tables seat four. In the center of this space, there are four main pillars. There are at least 50 seats available along the pillars. The bottom area in the map shows there are two other stalls: Go Go Curry and Sapporo Ramen. Moreover, there are around 30 seats beside these food stalls. All these tables and chairs use the same white color and unified material, which makes the environment bright and tidy.

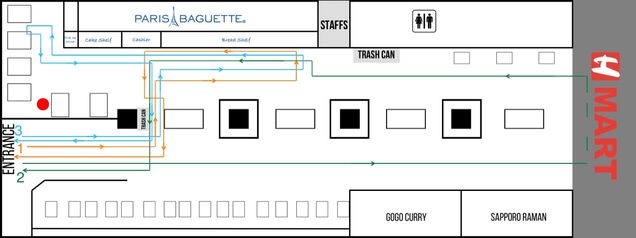

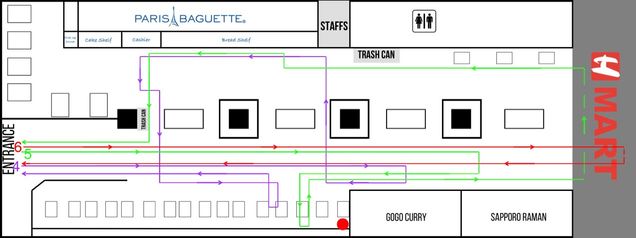

I arrived at the food court at 10:30 am on Thursday morning. I decided to observe the space for at least 2 hours. I chose this time range because it was not lunch time during the first hour from 10:30 to 11:30. And more people would come here for lunch in the second hour from 11:30 to 12:30. In the first hour, I chose the table that is not far from Paris Baguette Café cashier which is the red dot shown in Figure 2. This spot was close to the entry, and also gave me a great view of the whole café. One hour later, I changed my seat to the red dot in Figure 3, so that I could observe more clearly the people who came to have lunch.

The first interesting finding in my data is the vast majority of the customers at Paris Baguette Café were women, unaccompanied or only with their kids. There were very few male customers at the café. Even during the lunch time, the most people who went to Paris Baguette Café to buy a drink or a dessert were women as well. How do we explain this? Scholars like Bentley (1998) suggest that we look closely at gender in foodscapes. Bentley argues that red meat is associated with masculine virility, while sugar has been identified with femininity by other scholars (e.g., Avakian and Haber 2005). According to Farnham (2014), in Brtitain “men are more likely to visit a coffee shop on a daily basis, whereas women are more likely to visit 2-3 times a week. Women tend to stay longer once they get there though and they are more likely to use a coffee shop for socializing as well. Women are also more adventurous than men in the new drinks they are willing to try.” This phenomenon is worth exploring at Paris Baguette Café at different time periods and on different days.

According to my observation, I found that most people who come to Paris Baguette Café would like to spend a little time in front of the bread display cabinet, even if some of them didn’t buy anything. As Huddleston and Minahan (2011, 108) observe, “Creative and attractive merchandise displays draw customers in.” However, unlike most coffee shops today, Paris Baguette Café in the H Mart doesn’t have power sockets and WIFI. Although the café offers a very comfortable dining area for its guests, there would be more customers if they provided this supplementary service.

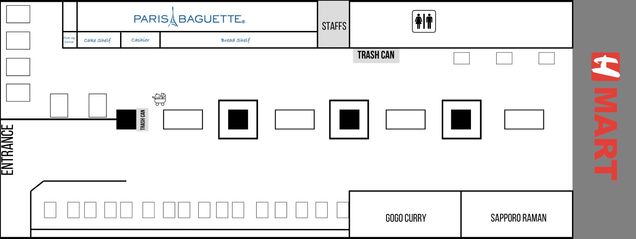

Another interesting conclusion I noticed involved the pattern of foot traffic. As you can see from the map, people always chose the narrow path opposite the cashier as an exit, regardless of which direction they came from. Nevertheless, if someone used the table between the first two pillars which are close to the main entrance, especially a mother with a stroller, that narrow path would be blocked (Figure 4). Meanwhile, with the increasing number of customers at the peak time, the two main pathways on both sides of the middle seating area became very messy. There is no defined place to queue while customers are buying the food. The issue is worth exploring more to create a better idea to use the space.

Unlike food observation, food mapping can be used as a tool to promote dialogue with retailers and policy makers. Food mapping could help bring positive change and effective strategy. As Wight and Killham note (2014, 314), “Food mapping is a new, participatory, interdisciplinary pedagogical approach to learning about our modern food systems. […] This experiential exercise encourages participants to look beyond their plates and think about the health, economic, and ecological impacts of food.” Moreover, food mapping can describe physical and economic relationships with food, and illustrate people's preferences and behaviors. The effort and meaning involved in producing meaningful food maps should never be underestimated.

References

Avakian, Arlene Voski, and Barbara Haber, eds. 2005. From Betty Crocker to Feminist Food Studies: Critical Perspectives on Women and Food. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Bentley, Amy. 1998. Eating for Victory: Food Rationing and the Politics of Domesticity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Farnham, Jacqui. 2014. Women and the Coffee Shop Revolution. Business Boomers. BBC Two. Date of access, June 07 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2QHz8CcHJV1wqxSjK77M4q7/women-and-the-coffee-shop-revolution

Huddleston, Patricia, and Stella Minaha. 2011. Consumer Behavior Women and Shopping. New York: Business Expert Press, LLC.

Wight, R. Alan, and Jennifer Killham. 2014. Food Mapping: A Psychogeographical Method for Raising Food Consciousness. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 38(2): 314-321.

Summer Course Spotlight: Culture and Cuisine of New England

Looking to add another course to your summer schedule, but unsure how to choose? You might consider Netta Davis's course, Culture and Cuisine of New England. Without fail, this course receives rave reviews from all who take it -- from students who have lived in the region for years to those who moved here just for school.

Fall 2019 Course Spotlight: Experiential Courses in Food and Wine

The following Fall 2019 courses are organized by the Programs in Food & Wine and are open to both degree-seeking students and as non-credit certificates.

MET ML 698 – Saturday Laboratory in the Culinary Arts: Cooking

8 Saturdays, 10am – 4pm, September 7 – October 26

This intensive, hands-on course will expose students to the essential skills and techniques that are the foundation of any culinary career. Students will engage in lectures and demonstrations and acquire applied experience in our spacious, state-of-the-art laboratory kitchen. From simple techniques to more difficult and complex preparations, students will develop valuable cooking skills, including:

- Foundations of cookery: stocks, soups, sauces, knife skills

- Production cookery: sautéing, roasting, frying, stewing, braising, simmering, poaching, grilling

- Bread and pastry: cakes, pastries, tarts, cookies, breads

- Sanitation, safety and the proper handling of food

This intensive, Saturdays-only course offers a condensed version of the full-time Certificate Program in Culinary Arts to students with weekend availability.

MET ML 700 - Certificate Program in the Culinary Arts: An Intensive, Hands-On Cooking Course (Multiple Instructors)

Mondays –Thursdays, 10am-6pm, September 5 to December 12

In the spring of 1989 Boston University held the first class in the Certificate Program in the Culinary Arts. Cofounded by Rebecca Alssid, Julia Child, and Jacques Pépin, this intensive, semester-long program was developed to expose student to classic French and American techniques, baking, and international cuisines, sustainability and many more subjects. The unique program merged the best aspects of traditional culinary arts study with the hands-on tutelage of a wide range of chefs—augmented by insight into the food industry as a whole. This model allows students to enter a wide variety of jobs related to food as well as continue their education in the Gastronomy Program. Merging the best aspects of the traditional culinary arts with hands-on instruction in BU’s state-of-the-art laboratory kitchen, the program provides insight into the food industry and prepares students for a variety of professional roles.

The only one of its kind in the country, Boston University’s full-time culinary arts program – entering its third decade – is taught entirely by working chefs and experts in the food industry.

Enrollment is limited to 12 students.

For more information, please call 617-353-9852 or visit www.bu.edu/foodandwine/culinary

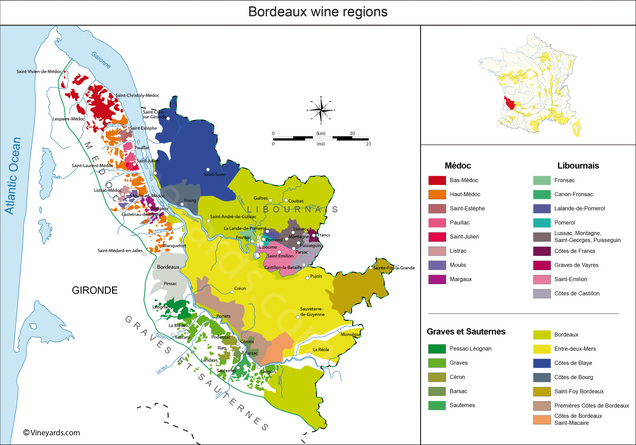

MET ML 651 - Level 1: Fundamentals of Wine – An Introduction (Bill Nesto, Ara Sarkissian)

Prerequisite: none, 2-credit course

Mondays, 6-9pm, September 9 – November 9

Suitable for students without previous knowledge of wine, this introductory survey explores the world of wine through lectures, tastings, and assigned readings. By the end of Level 1, students will be able to:

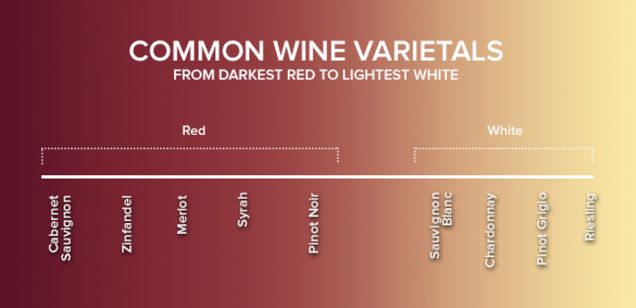

- Exhibit fundamental knowledge of the principal categories of wine, including major grape varieties, wine styles, and regions

- Correctly taste and classify wine attributes

- Understand general principles of food and wine pairing

- Comprehend the process of grape growing and winemaking

MET ML 652 - Level 2: A Comprehensive Survey of Wine (Bill Nesto, Beth Ann Dahan)

Prerequisite: none, but Level 1 recommended

Tuesdays, 6-9pm, September 3 – December 10

This intensive survey is designed for the avid consumer and serious student of wine. Offering detailed knowledge of wine through tastings, lectures, and assigned readings, the course is also useful for those who wish to enter the wine trade, or those in the industry who want to hone their knowledge. By the end of Level 2, students will be able to:

- Exhibit detailed knowledge of wine regions, grape varieties, and styles

- Demonstrate refined tasting ability

- Understand inherent characteristics of wine

MET ML 653 - Level 3: Mastering Wine – Skill Development (Bill Nesto, Beth Ann Dahan)

Prerequisite: a passing grade in Level 2

Wednesdays, 6-9pm, September 4 – December 11

This interactive and dynamic course is the first step in the mastery of the world wine industry. Intensive independent research, group presentations, and wine tastings enable students to gain advanced knowledge of wine production distribution, and consumption. By the end of Level 3, students will be able to:

- Identify wines accurately in blind tastings, including grape varieties and regions

- Appreciate the structure of the wine business at the local, national, and international levels

- Fully understand wine grape growing, vinification, maturation, bottling, and quality control

- Comprehend the theoretical interaction and synergy between wine and food pairing

MET ML 654 - Level 4: The Wine Trade – Global, National, and Local Perspectives (Bill Nesto, Beth Ann Dahan)

Prerequisite: a passing grade in Level 3

Thursdays, 6-9pm, September 5 – December 12

Students continue to develop mastery of the global wine industry through in-depth discussions and forums, research of current issues in the wine industry, interaction with experts in the field, and by tasting wines of exceptional quality. By the end of Level 4, students will be able to:

- Use their wine tasting skills to deconstruct and understand wine quality and origins

- Refine their wine vocabulary and comprehensive observations

- Effectively communicate about wine

- Speak and write confidently about current issues in the wine industry

MET ML 650 - Beer and Spirits (Sandy Block)

Thursdays, 6-9pm, September 5 – October 24

This class will cover the history, production, techniques, and classifications of all the major beer and spirits categories. Together with Master of Wine Sandy Block, VP of Beverage at Legal Sea Foods, students will taste and become thoroughly familiarized with the differences among beers and spirits, learn about the ingredients that create these classic beverages, and discuss trends in the beer and spirit industries in the United States and worldwide. This survey course is ideal for people who have an interest in beer and spirits, but would like to have a greater in-depth understanding of the richness and diversity comprising these categories.

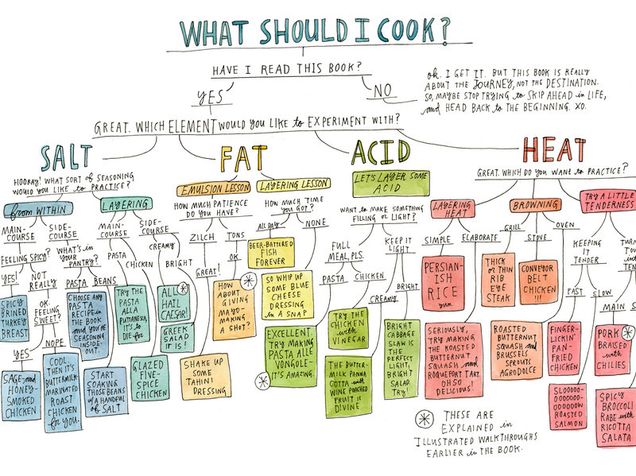

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat added to BU Gastronomy Core Courses

The Gastronomy Program has made exciting changes to the requirements for its MLA degree in Gastronomy. Of the 40 credits required to graduate with the Master’s of Liberal Arts degree, 16 have always been set aside as required classes. Whereas previously Gastronomy students were forced to take 4 specific courses to graduate (Introduction to Gastronomy, Food and the Senses, Food History, and Anthropology of Food), now students will have more flexibility in their requirements.

“Students will be asked to complete one course each that satisfies the criteria of Salt, Fat, Acid, and Heat,” explained Gastronomy Program Director, Dr. Megan Elias. Similar to the new BU HUB requirements for undergraduates, this new structure ensures students enroll in a broad range of classes, but that they select individual courses according to their personal goals. “These new requirements really get at the heart of a Liberal Arts course of study,” Elias said, “and place the Gastronomy program as a whole at the center of a new trend in the American foodscape.”

Students looking to graduate soon may be wondering which courses satisfy each category. “Figuring out which courses counted as which category was part of the fun of building this new system,” said Gastronomy Program Manager Barbara Rotger. “The course Food and Gender fits in the category of Acid, because learning about the role of the patriarchy in the food system will leave a sour taste in anyone’s mouth.”

To complete the Fat requirement, students can choose between our Saturday Baking Culinary Lab (plenty of butter there) or Debating Diet. Fun Gastronomy fact: the original proposed title for the Debating Diet course was “The Big Fat Fat Controversy.”

Courses which satisfy the Salt requirement all encourage students to engage directly with the mineral, including Science of Food and Cooking, with a full unit on NaCl, and the Wild and Foraged class, wherein students boil seawater for hours to harvest their own salt. Rumor has it Mark Kurlansky will even join the BU Faculty to teach a Salt class in 2020.

“All summer courses will satisfy the Heat requirement, naturally” explained Dr. Elias, “as will all courses that take place in a kitchen. You know what they say, if you can’t stand the Heat, you won’t graduate with an MLA.”

April Fool's from your friends at BU Gastronomy!!

Summer 2019 Courses

2019 Summer Session 1 Gastronomy Classes (May 21 through June 28)

MET ML 641 - Anthropology of Food (Karen Metheny)

Mon./Wed. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 1 (May 22-June 26)

What can food tell us about human culture and social organization? Food offers us many opportunities to explore the ways in which humans go about their daily lives, from breaking bread at the family table to haggling over the price of meat at the market to worrying about having enough to eat. In this course we consider how the anthropology of food has developed as a subfield of cultural anthropology.

Read the course spotlight here.

MET ML 673 - Survey of Food and Film (Potter Palmer)

Mon./Wed. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 1 (May 22-June 26)

We can all take pleasure in eating good food, but what about watching other people eat or cook food? This course surveys the history of food in film. It pays particular attention to how food and foodways are depicted as expressions of culture, politics, and group or personal identity.

MET ML 714 - Urban Agriculture (Zachary Nowack)

Tues./Thurs. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 1 (May 21-June 27)

What do gardens in cities do for people? Urban agriculture is a catch-all term that covers community gardens, vegetable plots at prisons, didactically-minded gardens in schoolyards, gardens planted illegally on vacant lots, high-tech hydroponic companies, and farmers’ markets. Students will develop knowledge about how these different spaces differ across variables like legality, goals, and actors.

Check out the class site here.

MET ML 651 - Fundamentals of Wine (Bill Nesto)

Tues./Thurs. 6-9 pm, Summer 1 (May 21-June 18)

Suitable for students without previous knowledge of wine, this introductory survey explores the world of wine through lectures, tastings, and assigned readings. By the end of the course, students will be able to exhibit fundamental knowledge of the principal categories of wine, including major grape varieties, wine styles, and regions; correctly taste and classify wine attributes; understand general principles of food and wine pairing; and comprehend the process of grape growing and winemaking.

2019 Summer Session 2 Gastronomy Classes (July 1 through August 9)

MET ML 638 - Culture and Cuisine: New England (Netta Davis)

Tues./Thurs. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 2 (July 2-August 8)

How are the foodways of New England's inhabitants, past and present, intertwined with the history and culture of this region? In this course, students have the opportunity to examine the cultural uses and meanings of foods and foodways in New England using historical, archaeological, oral, and material evidence.

MET ML 713 - Agricultural History (Gabriella Petrick)

Mon./Wed. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 2 (July 1-August 7)

This course surveys the history of American agriculture from the colonial era to the present. It examines how farmers understood markets, made crop choices, adopted new technologies, developed political identities, and sought government assistance. Emphasis is on the environmental, ideological, and institutional impact of farm modernization and industrialization.

MET ML 702 - Grapevine Varieties and their Varietal Wine (Bill Nesto)

Tues./Thurs. 5:30-9 pm, Summer 2 (July 2-August 8)

This survey course provides advanced wine students with a thorough knowledge of the wine world's principal grape vine varieties and their respective varietal wines. Students will learn about their history and their role in the market.

Prereq: a passing grade or higher in Level 2, or a grade of B- or higher in MET ML 652

More new students for spring 2019

Enjoy getting to know some of the new students who will be joining the Gastronomy Program in January.

Enjoy getting to know some of the new students who will be joining the Gastronomy Program in January.

A native of Claremont, CA (Los Angeles), Michelle-Marie Gilkeson lived in Chicago for two years while earning a Master’s in Women’s and Gender Studies at Roosevelt University. After returning to Los Angeles in 2011, she became a member of the IMRU Radio Collective, a group that has produced an LGBTQ radio show on KPFK-fm since 1974. Along with producing stories for air, she was the show director. A lifelong dancer, she was a member of Dorn Dance Company for five years, performing throughout southern California and eventually becoming the company’s Managing Director. In 2017, she and her husband left LA and traveled throughout Europe and Southeast Asia for ten months. While abroad, Michelle-Marie worked on creative writing projects and began her education in the field of Nutrition, studying remotely under Andrea Nakayama of the Functional Nutrition Alliance. She brings together her love of food and cooking, her nutrition philosophy, and her commitment to social justice to launch Dynamic Pantry, a resource for nutrition counseling and cooking workshops that keeps pleasure and connection central to discussions of health. She is thrilled to be a part of the Gastronaut community and to broaden her knowledge and skills.

A native of Claremont, CA (Los Angeles), Michelle-Marie Gilkeson lived in Chicago for two years while earning a Master’s in Women’s and Gender Studies at Roosevelt University. After returning to Los Angeles in 2011, she became a member of the IMRU Radio Collective, a group that has produced an LGBTQ radio show on KPFK-fm since 1974. Along with producing stories for air, she was the show director. A lifelong dancer, she was a member of Dorn Dance Company for five years, performing throughout southern California and eventually becoming the company’s Managing Director. In 2017, she and her husband left LA and traveled throughout Europe and Southeast Asia for ten months. While abroad, Michelle-Marie worked on creative writing projects and began her education in the field of Nutrition, studying remotely under Andrea Nakayama of the Functional Nutrition Alliance. She brings together her love of food and cooking, her nutrition philosophy, and her commitment to social justice to launch Dynamic Pantry, a resource for nutrition counseling and cooking workshops that keeps pleasure and connection central to discussions of health. She is thrilled to be a part of the Gastronaut community and to broaden her knowledge and skills.

Courtney Hakanson is a digital marketing consultant specializing in the development and implementation of social media strategies. Over the course of her 10-year career built in New York, and now Boston, she has worked with an extensive roster of Fortune 500 clients across the hospitality, consumer packaged goods, culinary, and fashion sectors, including Marriott International, the Council of Fashion Designers of America, David Yurman, Ligne Roset, Pepperidge Farm, Mattel, Gallo Wines, and Michelin Guides.

Courtney Hakanson is a digital marketing consultant specializing in the development and implementation of social media strategies. Over the course of her 10-year career built in New York, and now Boston, she has worked with an extensive roster of Fortune 500 clients across the hospitality, consumer packaged goods, culinary, and fashion sectors, including Marriott International, the Council of Fashion Designers of America, David Yurman, Ligne Roset, Pepperidge Farm, Mattel, Gallo Wines, and Michelin Guides.

In addition to her job in marketing, Courtney is professionally trained in the culinary arts. In 2014, she briefly relocated to Paris to complete the Basic Patisserie intensive at Le Cordon Bleu, and subsequently continued her education at the Natural Gourmet Institute in New York City. Beyond her studies, she has gained valuable experience through part-time work in restaurants, and has served as a professional recipe tester for cookbook editors and authors.

Courtney loves all things gastronomic – possessing a deep appreciation for everything from fine dining to street food – and has been fortunate enough to experience a wide variety of culinary traditions throughout her lifetime. Courtney is eager to develop a better understanding of the role of food in shaping societies globally through culinary traditions, heritage, access and sourcing, and hopes to pursue a career in food policy while studying at Boston University.

Stacey Terlik is originally from Western Massachusetts. This area is where her curiosity in food first ignited as she spent time with her grandfather tending to his lush garden. Stacey saw how food could not only cultivate new growth, but build community. As a Political Science Major at St. Joseph’s University, Stacey was able to further pursue her interest in food by becoming involved in food justice issues and exploring the intersections of social, political, economic, and food issues.

Stacey Terlik is originally from Western Massachusetts. This area is where her curiosity in food first ignited as she spent time with her grandfather tending to his lush garden. Stacey saw how food could not only cultivate new growth, but build community. As a Political Science Major at St. Joseph’s University, Stacey was able to further pursue her interest in food by becoming involved in food justice issues and exploring the intersections of social, political, economic, and food issues.

Following graduation from St. Joseph’s, Stacey went on to participate in the Jesuit Volunteer Corp., where she coordinated a therapeutic horticulture program at an urban farm in St. Louis. Stacey’s time at the farm propelled her into her current role in community mental health, where she works with individuals to pursue their therapeutic recovery goals. The culmination of these experiences have made Stacey realize that her passion for community and justice is enriched when she incorporates her love for food and farming.

Stacey hopes that by pursuing her Master’s of Gastronomy at BU, she can continue to uncover how to work together with communities to combat food inequality, enact change, and grow hope. Stacey’s long term goal is to create an urban farm focusing on therapy and job training that feeds into a farm-to-table restaurant to promote community building through shared tables. She is confident that participation in this program will enable her to continue to build skills that will be essential in executing her vision.

Welcome New Students for Spring 2019

Enjoy getting to know some of the new students who will be joining the Gastronomy Program in January.

Hannah Brantley is a trained chef, feminist scholar and former nutritionist. She grew up in the Midwest and moved to Boulder, Colorado where she obtained her Culinary Arts and Nutrition Consulting certifications. After working as a line cook, chocolatier and personal chef, she began a nutrition consulting business specializing in gut and brain health. She primarily worked with women with bacterial and yeast overgrowths who were also experiencing cognitive impairment such as anxiety and depression. Beyond individual nutrition consulting, she also ran fermentation and gut health workshops where participants learned how to support their microbiome and make fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut. After working for several years in professional kitchens and the wellness industry, she is now primarily interested in the socio-cultural and political aspects of food practices and theory. After observing the oppressive, gendered nature of foodways, she completed her BA in Philosophy at the University of Missouri Kansas City where she began researching food from a feminist-philosophical perspective. She is fascinated by the philosophical implications of the everyday and mundane and how these contribute to identity such as race, class and gender. Some of her specific interests include making ferments such as yogurt and sauerkraut, entomophagy, perfecting her chili oil recipe and searching for the best olive oil and chocolate. She lives in Portland, Maine.

Hannah Brantley is a trained chef, feminist scholar and former nutritionist. She grew up in the Midwest and moved to Boulder, Colorado where she obtained her Culinary Arts and Nutrition Consulting certifications. After working as a line cook, chocolatier and personal chef, she began a nutrition consulting business specializing in gut and brain health. She primarily worked with women with bacterial and yeast overgrowths who were also experiencing cognitive impairment such as anxiety and depression. Beyond individual nutrition consulting, she also ran fermentation and gut health workshops where participants learned how to support their microbiome and make fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut. After working for several years in professional kitchens and the wellness industry, she is now primarily interested in the socio-cultural and political aspects of food practices and theory. After observing the oppressive, gendered nature of foodways, she completed her BA in Philosophy at the University of Missouri Kansas City where she began researching food from a feminist-philosophical perspective. She is fascinated by the philosophical implications of the everyday and mundane and how these contribute to identity such as race, class and gender. Some of her specific interests include making ferments such as yogurt and sauerkraut, entomophagy, perfecting her chili oil recipe and searching for the best olive oil and chocolate. She lives in Portland, Maine.

Kate Cherven grew up in St. Pete Florida and her passion for food grew slowly over the years through personal interest. She has used food as a creative outlet, a way to learn about others and a glue to bring people together. Now she is trying to turn her interests into a career. She graduated from the University of Iowa with majors in anthropology and English creative writing, and then moved to Auckland, New Zealand. After five years in Auckland, she built a career in marketing and communications within the non-profit industries. While working she joined the Cheap Eats Blog team as a writer and a content creator for their blog and social media platforms. By working on the Cheap Eats blog, Kate realised she wanted to make her hobby into her career. She applied to the MLA in Gastronomy at BU and decided to move back to the US with her Kiwi partner Stefan. She has two passions: learning about cultures and understanding the relationship between people, food and the environment. Kate is looking forward to the program, getting to know Boston and eating heaps of delicious food along the way.

Kate Cherven grew up in St. Pete Florida and her passion for food grew slowly over the years through personal interest. She has used food as a creative outlet, a way to learn about others and a glue to bring people together. Now she is trying to turn her interests into a career. She graduated from the University of Iowa with majors in anthropology and English creative writing, and then moved to Auckland, New Zealand. After five years in Auckland, she built a career in marketing and communications within the non-profit industries. While working she joined the Cheap Eats Blog team as a writer and a content creator for their blog and social media platforms. By working on the Cheap Eats blog, Kate realised she wanted to make her hobby into her career. She applied to the MLA in Gastronomy at BU and decided to move back to the US with her Kiwi partner Stefan. She has two passions: learning about cultures and understanding the relationship between people, food and the environment. Kate is looking forward to the program, getting to know Boston and eating heaps of delicious food along the way.

Meghan Glass grew up in the suburbs of Maryland. After growing out of a picky eater phase, she eventually enjoyed exploring Chinese, Indian, Japanese and Thai food. She attended Boston University graduating with a B.A. in Anthropology and Gender Studies. Meghan then moved to Michigan for a job in health care survey design for a small company.

Meghan Glass grew up in the suburbs of Maryland. After growing out of a picky eater phase, she eventually enjoyed exploring Chinese, Indian, Japanese and Thai food. She attended Boston University graduating with a B.A. in Anthropology and Gender Studies. Meghan then moved to Michigan for a job in health care survey design for a small company.

The food scene in Ann Arbor expanded her horizons to include the cuisines and dishes of Cuba, Ethiopia, Korea and Yemen as well as develop a love for Zingerman’s Delicatessen. She hosted numerous dinner parties and joined a jamming and canning group. It was through these communal food experiences she recognized her desire to bring joy to people through her food. Meghan completed the Culinary Arts program in the fall of 2018 and decided to continue her food education through the Gastronomy Masters program. She hopes to work in a test kitchen environment, recipe development, or reviewing restaurants professionally.

In her free time, Meghan enjoys reading, going on cruises, exploring new recipes and restaurants, as well as judging crab cakes with her new husband.

Jie Liu was born and raised in Hefei, a city in the middle east of China. In 2012, after her postgraduate study in Economics at the University of Manchester, she went back to Beijing to work in a bank.

Jie Liu was born and raised in Hefei, a city in the middle east of China. In 2012, after her postgraduate study in Economics at the University of Manchester, she went back to Beijing to work in a bank.

Because she was away from home alone for a long time, Jie started to learn to cook. In 2015, She move to Boston with her husband. During the three years absent from work, she has more time to spend in the kitchen. She challenged herself different recipes every time and fell in love with baking. She found that she never miss the old days in the bank at all. She would like to do something more creative and something she is really interested in.

Jie is also a fan of documentaries about food. Her favorite is Once upon a Bite. Those documentaries reveal the connection between the food and cultures, so she is inspired to study the food as a subject. And in the future, she is looking forward to work in food media.

Stepping into the food world is a delicate decision for her. She believe the Gastronomy program can give her an opportunity to pursue her dream and eventually to make her passion into her profession.

Announcing the Spring 2019 Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy

Programs in the Pépin Lecture Series in Food Studies & Gastronomy are free and open to the public, but registration is requested. All lectures begin at 6 PM and will be held in room 313 of BU’s College of Arts and Science Building, 725 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA.

Building Nature’s Market: The Business and Politics of Natural Foods

Laura Miller, Associate Professor of Sociology, Brandeis University

Wednesday, March 6 at 6 PM, CAS 313

Building Nature’s Market shows how the meaning of natural foods was transformed as they changed from a culturally marginal, religiously inspired set of ideas and practices valorizing asceticism to a bohemian lifestyle to a mainstream consumer choice. Laura J. Miller argues that the key to understanding this transformation is to recognize the leadership of the natural foods industry. Rather than a simple tale of cooptation by market forces, Miller contends the participation of business interests encouraged the natural foods movement to be guided by a radical skepticism of established cultural authority. She challenges assumptions that private enterprise is always aligned with social elites, instead arguing that profit-minded entities can make common cause with and even lead citizens in advocating for broad-based social and cultural change.

The Physics of Food and Cooking

Professors Karl Ludwig and Rama Bansil, Boston University Physics Department

Tuesday, March 19, 2019, CAS 313

Professors Ludwig and Bansil teach The Physics of Food and Cooking at Boston University. The course explores physical science concepts of thermal / soft matter physics and molecular biophysics such as phase transitions and gelation, viscosity, elasticity illustrated via cooking. Class activities and labs demonstrate molecular gastronomy methods of sous-vide cooking, pressure cooking, making desserts, cheese, emulsions, foams, gels, and ice creams.

A Taste of Broadway: Food in Musical Theater

Jennifer Packard, MLA in Gastronomy, author of A Taste of Broadway: Food in Musical Theater

Thursday, April 4, 2019, CAS 313

Beyond being just fuel for the body, food carries symbolic importance used to define individuals, situations, and places, making it an ideal communication tool. In musical theater, food can be used as a shortcut to tell the audience more about a setting, character, or situation. Because everyone relates to eating, food can also be used to evoke empathy, amusement, or shock from the audience. In some cases, food is central to show’s plot. This book looks at popular musical theater shows to examine which foods are used, how they are used, why they are important, and how the food or usage relates to the broader world. Included are recipes for many of the foods that are significant in the shows discussed.

Feeding Europe under British Rationing: Relief Efforts for the Continent after the Second World War

Kelly Spring, Food Historian and Visiting Professor, University of Southern Maine

Thursday, April 18, CAS 313

This research examines the complexities of Britain’s post-war position through the lens of its food relief to Europe. Specifically, it investigates the relief efforts of the Council of British Societies for Relief Abroad, which worked with the British government, the UNRRA and voluntary societies to feed the women and children of Europe, particularly those living in Germany and Austria. It demonstrates that relief initiatives shifted overtime in the contexts of domestic considerations, British foreign policies and international relations. This research offers an important, new perspective on Britain’s shifting transatlantic relations and tensions with the United States and Europe in the early days of the Cold War.

Course Spotlight: Food and Public History

Got Food? Got History? Go Public.

Food and Public History (ML623), Spring 2019

In Food and Public History ( 4 cr), we will examine interpretive foodways programs from museums, living history museums, folklore/folklife programs, as well as culinary tourism offerings, "historical" food festivals, and food tours. Our goal is to compare different way to teach the public about history or cultural heritage using food, and teach the public about the history of food. How do we engage the public? How do we demonstrate the relevance of food as both a historical subject and as a topic of interest today? Through different approaches to public history, can we connect our audience to issues that are so critical today—the future of food movements, for example, or the preservation and understanding of cultural difference? How can we successfully engage the public, whether through displays, tours, or interactive/sensorial experience?

Students will have the opportunity to hear from several experts in historical interpretation, public history, and food history programs. We will be taking field trips to area museums and food history walking tours in Boston. These visits will serve as case studies, allowing students will examine the process of creating mission statements, interpretive goals, and entrepreneurial offerings, as well as different methods of communicating with the public. This is also a project-based course involving experiential learning and hands-on learning opportunities. Student projects will include creating proposals for food history tours in the North End and proposing a food-related exhibit. Finally, student will participate in a semester-long group project, entitled Home Cooks in the Merrimack Valley. The project will include several stages of work, including background research, drafting a project proposal, drafting a grant proposal, drafting a script and proposal for the Boston University Institutional Review Board (IRB), and fieldwork (interviewing home cooks from a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds), transcribing those interviews, and then creating or adding to an online exhibit.

Hope you will join us!

For more information, contact kmetheny@bu.edu.

MET ML 623, Food and Public History, will meet on Tuesday evenings from 6:00 to 8:45 PM, starting on January 22, 2019. You can register here.