Course Spotlight- Reading and Writing the Food Memoir

MET ML615, Reading and Writing the Food Memoir will be taught this spring by Dr. Megan Elias and will meet Wednesdays from 6 to 8:45 PM

What is your food story? If we are what we eat, what foods made you who you are? Was it fruit from a country you no longer live in or a soup your best friend made when you visited him last week? Did it pour out of a box? Get toasted over open flames? Simmer for a day? And how do you explain its role in your life? Food can be a great connecting theme for a complicated story.

In this course we will ask what makes a food memoir different from other kinds of personal writing and we will work on our own unique food memoirs. Food memoir can take lots of forms, including visual narrative, comics, film, podcast, poetry, walking tour, and creative non-fiction. We will study some examples to learn about the form and workshop our memoirs while we write them. We will also spend some time in the kitchen together cooking from our projects to find out what we can learn by engaging with the material of food itself.

I come to this class with eight years of experience teaching Food Studies at BU and an active research agenda in food history. My recent scholarship focuses on stories about food. I have read a lot of food memoirs but have never written my own and am excited to try it out in community with the class.

Some of the works we will be sampling are:

Thomas Pecore Weso, Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir

Kwame Onwuachi, Notes from a Young Black Chef

Von Diaz, Coconuts and Collards

Yeon-sik Hong, Umma’s Table

Nigel Slater, Toast (movie version)

You will also have an opportunity to suggest material for us to discuss in class.

Course Spotlight – Debating Diet

“Those in closest proximity to structural ‘power’ shape our food, body, and health beliefs.” - Patrilie Hernandez, Founder of Embody Lib.

Fat studies meets food studies in a recently revised course. MET ML613 - Debating Diet, will be taught online in Spring 2025 by Catie Duckworth.

Course Description: “Diet” hails from the Greek word “diaita” meaning “way of life.” The English word, originally used to describe the food and beverages people regularly consumed, eventually came to be used to categorize a restrictive way of eating, specifically with the goal of weight loss. Evidence of diet culture can be found in nearly every aspect of Western society, from media to nutrition advice. This course will bring together the fields of fat studies and food studies by exploring different meanings of the word diet and in the process dissecting the socio-political influence of diet culture on our food systems, eating habits, and moral associations with food. The course materials will trace the history of anti-fatness from its root in anti-blackness to infiltrating the modern Western healthcare system. Students will have the opportunity to expand their understanding of nourishment through additional functions of food (joy, pleasure, comfort, community, etc.).

My (Catie’s) research focus sits at the intersection of food studies and fat liberation. I am a trained culinarian, a graduate of the Gastronomy program, and a fat liberationist. My most recent energies have been devoted to developing this course and my volunteer work with Bigger Bodies Boston, a fat liberation collective. It is not only my work but my lived experience as a fat woman that have shaped my understanding of this subject. And I admit with still more to learn, as my positions as a white, educated, cis-gendered person allow me certain privileges denied to more marginalized identities within the fat community.

It is with acknowledgement of my relative privilege that I aim to bring an inclusive fat studies lens into the food studies discipline, inviting guest speakers to expand beyond my own expertise. Readings will include foundational texts like Sabrina Strings' Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Julie Guthman's Weighing In. Some weeks will include more hands-on activities, such as reviewing cookbooks in search of morally coded messages.

Through the texts, class activities, and guest lectures, this course will address the following questions:

- Who benefits from diet culture? Who is harmed?

- Why do we label foods as "good" or "bad"?

- What does "good food" and "bad food" even mean?

- What are the goals of fat liberation/body liberation?

- In what ways do these goals conflict with the dominant narratives on food justice?

- What if optimal individual health is not everyone's goal?

- How can we decolonize "nutrition" and "wellness"?

- What different moral values can we decode in language around food/eating?

- And many more that we will discover along the way!

Course Spotlight- Culture and Cuisine: New England

MET ML 638, Culture and Cuisine: New England will be taught this Spring 2025 on Wednesday from 6:00-8:45 p.m. by Dr. Karen Metheny

MET ML 638, Culture and Cuisine: New England will be taught this Spring 2025 on Wednesday from 6:00-8:45 p.m. by Dr. Karen Metheny

C ourse Description: How are the foodways of New England’s inhabitants, past and present, intertwined with the history and culture of this region? In this course, students will have the opportunity to examine the cultural uses and meanings of foods and foodways in New England using historical, archaeological, oral, and material evidence. We will focus on key cultural, religious and political movements that have affected foodways in the region, as well as the movement of people. The course begins with an examination of Native American food traditions and practices in the pre-contact period. We will also consider how foodways mirrored the clash of cultures during an extended period of contact and settlement by Europeans.

ourse Description: How are the foodways of New England’s inhabitants, past and present, intertwined with the history and culture of this region? In this course, students will have the opportunity to examine the cultural uses and meanings of foods and foodways in New England using historical, archaeological, oral, and material evidence. We will focus on key cultural, religious and political movements that have affected foodways in the region, as well as the movement of people. The course begins with an examination of Native American food traditions and practices in the pre-contact period. We will also consider how foodways mirrored the clash of cultures during an extended period of contact and settlement by Europeans.

How did the Pilgrim settlers respond to a new environment and to new foods in the New World? How did perceptions of their own Englishness change? Old-fashioned Yankee fare is considered emblematic of traditional New England by many writers, and we will consider why this perception exists and when it developed. But New England foodways have also been greatly influenced by immigrant groups in the 19th and 20th centuries. Students will therefore look closely at the food preferences, traditions, and subsistence practices of the Irish, Italian, and Portuguese immigrant communities in New England. We will also look at two cultural phenomena in 20th-century New England—roadside diners and tea houses—to understand the changes wrought by the introduction of the automobile and the interstate highway system, as well as the larger impact of industrialization and commercialization of foods.

Students will travel to Old Sturbridge Village to prepare and enjoy a 19th-century hearth-cooked meal and tour the museum. Other trips to be determined.

Course Spotlight- “Cook Like a Pro”

We are thrilled to add our revamped course, “Cook Like a Pro” to our curriculum next semester: The hands-on, pared-down version of our culinary certificate program, designed for beginners and aspiring cooks alike. In this class you’ll be guided through the fundamentals of meal preparation, ingredient selection, and proper seasoning. You’ll learn how to master essential techniques, from handling a knife like a pro to chopping and sautéing to baking and plating, all while developing good kitchen practices and habits.

Classes take place in our state-of-the-art kitchen and are taught by the same team of highly acclaimed chefs who teach in our professional culinary program, including Jody Adams, Barry Maiden and Michael Leviton (instructors subject to change). While completion of this course does not result in a certificate, it offers a scaled-down version of our professional culinary program. The course covers all the basic core skills with a focus on key recipes and techniques.

For more about the course, we got the inside scoop from Chef Chris Douglass, Lead Instructor of BU’s Culinary Arts program.

- Why offer this course when we already offer a certificate program?

“Our certificate program, while amazing, is a big commitment. But cooking is an essential and basic skill, one you can employ your entire life. This course is meant to give you the tools to confidently navigate the kitchen and professional techniques without that commitment of our more intense program. Another key aspect of this course is access to some of the most respected chefs in the industry, so whether you have zero cooking experience or are interested in building knowledge, you have a fantastic opportunity to work with professionals and receive real feedback.”

- What type of student is this course really for?

This class is truly for anyone. We designed the curriculum to accommodate varying skill levels, from someone who doesn’t know how to boil water to someone who wants to refine their technique and palate.

- What should students expect a typical class period to look like?

“Students can expect to build on fundamentals at the beginning of the course, before moving onto more advanced material. They will prepare 2-4 recipes each week with a focus on technique and exploration of flavors. From basic knife skills and application of heat, all the way to honing techniques, students will learn how to cook with staples like eggs, vegetables, meat and fish.”

- What will students take away from this course?

“Students will leave with more confidence to tackle recipes on their own without hesitation. What could be better than that?”

---

Course details— Non-Credit Cost: $1,800, Meets: Mondays 6:00 - 8:45 pm, January 27 - April 28, 2025

Course Spotlight: Artisan Cheeses of the World

A course centered entirely around cheese? You aren't dreaming, it's real! Taught by Kimi Ceridon, Instructor for the Artisan Cheese Program at Boston University and owner of Live Love Cheese, this class provides an in-depth exploration of the styles and production of cheeses from local to far-reaching regions worldwide. The class is a blend of tastings, experiential classwork, discussion and lectures on cheese, the cheese industry, and cheesemaking. Successful completion of the course will result in a Certificate in Cheese Studies from Boston University.

With an emphasis on understanding the production of cheese, you'll learn about everything from culturing to affinage, and how variations in each process (and those in between) affect its organoleptic properties. You'll also use cheese as a case study in historical and cultural contexts to better understand the relationship and connections between people and food. As an experiential class with hands-on classwork and in-class tastings, each day of class will be exciting, challenging and different, from the cheeses of Southern France one day to a guest panel of cheese experts the next. And later in the semester, you'll take part in a full-day ethnographic tours of cheesemaking farms in New England. You'll visit farms in Vermont to meet with cheesemakers and staff, tour the farm dairy and cheesemaking facility, and observe the cheesemaking process.

Running again in Spring 2025, this course is open to both BU Gastronomy students and non-credit students. Learn more and register here.

We caught up with Kimi for a deeper look inside the program:

I initially entered the Gastronomy program because I was interested in local food systems. While earning my MLA, I took the Artisan Cheese Program, and I was immediately excited about how artisanal cheese was. This product encompasses so much about local food systems, from ecology to small family farms to the circular economy to consumers connecting with local foods and makers. There's also the nerdy part of me that loved cheese. I have a master's degree in mechanical engineering from MIT. While I left the STEM field, I still loved science and cheese is this awesome intersection between science and food. It takes science and craft to turn milk, enzymes, molds, cultures and salt into thousands of distinct varieties of cheese. Cheese is magical like that. And, of course, cheese is also super yummy.

In 2024, Kimi Ceridon, the founder of Life Love Cheese, made Culture Magazine's Hot List of Cheese Professionals for her work educating people about the magic of cheese. Kimi received her MSME from MIT in 2001. She spent over a decade in tech before saying "Goodbye" to the cubicle and starting culinary school. She has an MLA in Gastronomy and an Artisan Cheese Certificate from BU. She's also trained in cheesemaking at Sterling College alongside Jasper Hill. Now, she is an artisan cheese instructor at BU. Her company, Life Love Cheese, focuses on highlighting American cheese makers and artisans with a special emphasis on the Northeast. Look for her new store opening in Wakefield this Winter.

In 2024, Kimi Ceridon, the founder of Life Love Cheese, made Culture Magazine's Hot List of Cheese Professionals for her work educating people about the magic of cheese. Kimi received her MSME from MIT in 2001. She spent over a decade in tech before saying "Goodbye" to the cubicle and starting culinary school. She has an MLA in Gastronomy and an Artisan Cheese Certificate from BU. She's also trained in cheesemaking at Sterling College alongside Jasper Hill. Now, she is an artisan cheese instructor at BU. Her company, Life Love Cheese, focuses on highlighting American cheese makers and artisans with a special emphasis on the Northeast. Look for her new store opening in Wakefield this Winter.

Graduate Spotlight: Lucy Almirudis

We recently caught up with Lucy Almirudis (@lucialmirudis), a graduate of Boston University’s Certificate Program in Wine Studies and a member of the 2022 "Urban Grape Wine Studies Award for Students of Color" cohort. Learn more about her story below.

I was born and raised in Sonora, Mexico where I studied architecture and worked as an architect for a couple of years. Seeking a life change, I decided to spend the summer of 2014 in Boston. That's when I met my husband—and it turned into the longest summer of my life. I lived in Boston for a decade and during that time I worked in the restaurant industry, building a career in fine dining and event planning. That’s when I fell in love with wine; realizing that wine made every special occasion even more memorable and that people are willing to invest a lot in a good bottle.

I found out about "The Urban Grape Wine Studies Award for Students of Color" through my best friend and decided to give it a shot to build a career in the wine world.

- At the Urban Grape store to learn about retail

- With MS Walker to learn about importing and distribution

- At Row 34 to learn about the restaurant industry

- At Jackson Family Wines to learn about viticulture, sustainable farming, wine making, branding, marketing, production, direct to consumer, sales and more

Going through the program has been one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences I’ve been through. Because I was working in the restaurant industry and handling wine so closely every day at work; it meant having more very useful knowledge while going through what sounded like a very dynamic experience. I would’ve never imagined my life would end up taking such a drastic turn. I've met so many amazing people, I've learned so much about the wine industry and—the best part—got an opportunity to combine both of my careers: wine and architecture.

My last internship at Jackson Family Wines in California, where I spent time with their Real Estate Department, was particularly formative. It felt truly full circle seeing everything I had been studying and reading about during class in person. I finally got to see the grapes in person, taste them (the Chening Blanc grape is incredibly delicious), witness the wine being made and visit wineries I had only heard of. It was really special!

At the beginning of 2024, I got a job offer that moved me, my husband and our cats to California. I am currently working as an Assistant Project Manager as part of the Jackson Family Wines design team. While interviewing to be part of the Urban Grape Wine Studies Award someone said to me “Would you like to go back to work as an architect? The wine industry touches almost every other industry, your job could be designing wineries and tasting rooms” and I thought to myself “Does a position like that even exist?”

A year and a half later here I am, working with a team that focuses precisely on that, designing wine tasting rooms and guest houses. I would’ve never imagined that through a wine program I would go back to architecture, but I absolutely love it!

I couldn’t be more thankful for having the opportunity to be a part of this program and for my husband’s support through all of it. Thank you Urban Grape and Boston University!

To learn more about "The Urban Grape Wine Studies Award for Students of Color" and how to apply, please visit this resource.

Student Work Wednesday- Featuring Emily Shawn

This week we’re highlighting the work of Gastronomy graduate, Emily Shawn. Last spring, Emily completed a project about food innovation at Fenway Park for the Food Waste course taught by Steve Finn here at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

Exploring Food Innovation and Food Waste Reduction at Fenway Park

Swing, battah, swing! The sounds of Fenway Park resonated, practically surrounding me as I made my way through Lansdown Street. The unmistakable scents of baseball food – Fenway Franks, giant salted pretzels, popcorn, cracker Jacks – wafted over me, along with something fresh and summery on the mid-summer breeze. A baseball game at Fenway Park is a full heart-of-Boston sensory experience, from the thrill of flying baseballs, the fascinating people-watching, and the unforgettable culinary experience. When my Food Waste: Scope, Scale and Signals for Sustainable Change class visited the park in late June, we were lucky to have great weather and even catch a glimpse of a rainbow up above the Green Monstah.

I have to admit I was not expecting our tour of Fenway to include a beautiful garden, fresh veggies, and the best carrot I’ve ever eaten. After leading our class through the multiple kitchens within Fenway, through the glorious MGM concert hall, up above the Green Monstah and through the VIP kitchens, Senior Executive Chef Ron Abell directed our group up to a rooftop garden with lush flower beds and an equally stunning view of Boston.

The sight took my breath away, as did inhaling the refreshing earthy-floral scent so unexpectedly delightful in a decidedly urban city block.

“Who knows what these are?” Ron asked, pointing to several plants. Our class identified the herbs – lavender, basil, chives – and then stepped across a gate to enter the rooftop garden.

Fenway Farms, an urban rooftop garden grown in milk crates, provides fresh organic home-grown vegetables for thousands of baseball fans through the season. The use of rooftop space for growing plants provides an excellent atmosphere for vegetation to grow right next to the kitchen, in full sunshine and up far too high for any ground animals to reach.

“Let’s test your knowledge,” Ron offered, pointing at each plant to see who in our class could name the vegetables and pollinator flowers. Kale, lettuce, sugar snap peas, eggplant, tomatoes, nasturtiums, carrots – row upon row upon row of plants, all thriving and diligently cared for. The garden felt, in a way, magical.

As our class wandered through the garden in a sort of awe, Ron explained to us that he believes in cooking and eating seasonally. You can’t make butternut squash taste good in early May – it’s not right. And what better way to eat in tune with the seasons than a fresh vegetable garden, right here above the baseball field?

The garden was, in fact, practically the opposite of what I would have expected baseball food to be.

“A lot of this goes up to the VIP boxes,” Ron explained, twirling a freshly picked carrot in his hands. He explained that the box seats offer guests meals including fruit trays and wholesome salads all grown right here.

“Try this,” Ron then said, breaking off the carrot top and handing it to me. I frowned – don’t carrot tops usually go in the garbage? However curiosity got the best of me so I took a bite. It was crunchy, almost peppery, like a cross between lettuce and cilantro – surprisingly tasty!

As we chomped on the carrot and the carrot tops, Ron explained how he made sure the staff in his kitchens knew how to use vegetables, how to pick them, how to properly cook them, and how to slice and prepare them so as to minimize food waste in any fashion. His passion for food – good, seasonal, delicious, expertly-prepared food—was evident and drew us in as he talked about how the garden served the kitchens, staff, and guests of Fenway Park.

We discussed the many unique challenges of reducing food waste in stadium settings, to which Ron and his team are well-attuned, including the challenge of reducing waste in the luxury suites – which has parallels to other settings (ex. cruise ships, casinos) where consumers are paying up for a high-end experience with an expectation of abundant food. Indeed, Ron explained that a large percentage of food waste at Fenway involves produce, as patrons often bypass salads and fruit trays for more traditional ballpark fare.

Our class collectively shuddered: standing here in this beautiful garden, nibbling a carrot fresh from the earth, it was such a shame to think of any of these plants going to waste rather than nourishing people.

Ron’s dedication to the rooftop garden and ensuring the plants are used effectively in the kitchen really brings home how evident it is that as consumers (in all venues) we need to do better -- to ensure that we properly value our food resources so that all of the effort put into growing, distributing and preparing nutritious food for us is not also lost with discarded food.

At the same time, standing in the garden myself where I could see, smell, hear and taste the fresh veggies while also enjoying a fabulous view of the city of Boston really highlights the importance and benefits of urban garden access. When one is able to name every plant in a garden – our class came close but Ron Abell knew them all – the food feels even more important, meaningful, and (dare I say) delicious.

We are grateful for the tour and discussion and Ron’s dedication to his craft, which includes minimizing the waste of food in a unique and challenging environment.

---

A lesson I took into the future from eating leafy carrot tops is to find more uses for foods that surprise me. If you’re looking to keep your carrot tops out of the trashcan, try out this carrot top pesto recipe here: https://minimalistbaker.com/the-best-carrot-top-pesto/

You can also learn more about the Fenway Farms rooftop garden here: https://www.mlb.com/redsox/ballpark/green-initiatives/fenway-farms

Student Work Wednesday- Featuring Sarah Thompson

This week we’re highlighting the work of Gastronomy graduate, Sarah Thompson. Sarah completed a project in which she recreated a historical recipe for the Cookbooks and History course taught by Karen Metheny here at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

The Nameless Cake

The Nameless Cake—I feel kind of bad for this cake because in Malinda Russell’s 1866 A Domestic Cook Book, this recipe is placed among so many other named cake recipes but I think this one has just as much to offer! To show this cake the love and attention it deserves, I decided to try my hand at making the recipe. While the ingredient list was ever so simple, that’s pretty much the extent of the recipe: an ingredient list. There was no mention of temperature at which the baking should happen, nor was there a time given for how long the cake should be in the oven. There was no mention of any type of pan that is suggested to use. It is clear that Malinda Russell assumes her readers have baked many cakes in their day and they can infer the instruction portion. Another challenge was equating a “teacupful” to something I had in my kitchen arsenal. I decided I would use ½- ¾ of a coffee mug and call that a teacupful. It seemed to work, but I know the result could have been a little different had I been more accurate with my decision-making.

I thought it was so interesting that this cake was at the bare bones level as far as cake ingredients go, including just: flour, sugar, eggs, butter, and milk. I kept thinking while I was making this, I feel like I need more, a splash of vanilla, or lemon zest or baking soda, or something. But it did turn out delicious in the end. It is not a cake I am used to by any means, and I would accredit that to the lack of ingredients. When I tasted it, it was very spongy and sort of soufflé-like, probably because there were 5 eggs in there. All-in-all I really enjoyed this sort of sleuth-like cooking. I feel like when I bake a modern recipe, I know I will always be surprised at what comes out of the oven, but following this recipe (or ingredient list more like it) I was really flying blind. It goes to show however how much baking has changed as a form of cooking and the way chefs, and recipe-developers chose to include or exclude. Malinda Russell, I think it is clear in this recipe, at least maybe felt less was more. So, I think it is appropriate to euphemize perhaps and give a name rather than be Nameless forever in history, so let’s call it the Less is More Cake.

References:

Russell, Malinda, A Domestic Cook Book (Paw Paw: T.O. Ward, 1866), 14.

Student Work Wednesday- Featuring Nicole Baker

This week we’re highlighting the work of Gastronomy student, Nicole Baker. Nicole completed a project in which she recreated a historical recipe for the Cookbooks and History course taught by Karen Metheny here at Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

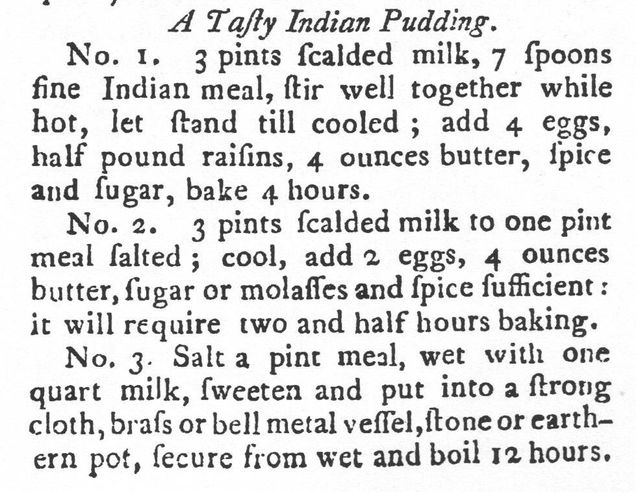

Sutton's Island's Corn Cake of 1889

How does one recreate a recipe from 1889 with little to no information beyond the ingredients? Well for one, we start with what we know, which is experience in food, baking, and cooking, thankfully! The Sutton Island Cookbook is a compilation of recipes collected by someone working in the Sutton Island kitchen from the years 1889-1897. This island is a part of the Cranberry Isles off the coast of Mt. Desert Island, which is modern day Acadia National Park.

The majority of these recipes, themselves, are clippings from what seems to be a multitude of sources, but there is the occasional handwritten recipe sprinkled throughout. The compiler even notes that this cookbook is also seen as a scrapbook. Perhaps these recipes were ones they admired to make, enjoyed themselves, or with which they accommodated guests for meals on the island.

For this recipe recreation in our Cookbooks and History class, I chose the “Corn Cake” recipe on page 73 of the book (Fig 1). Since the recipe only lists ingredients, there was a lot of room for trial and error. Because of the absence of directions, I felt this recipe would be quite a journey to embark on, and perhaps bring me more confidence in my baking skills. While there was plenty of room for interpretation and trial, I did want to get this recipe right on the first go, so as not to waste ingredients.

For the technical aspect of baking this cake, I remembered from my own experience that most cakes today are baked between 350°F and 400°F. As a result, I chose a temperature within this range. Further, as we learned in class, during this period wood burning ovens were most common for baking and cooking. Thinking of this, I imagined there be some fluctuation in temperature as well, not quite staying an even 375°F or 400°F, hence, I chose 380°F as the cooking temperature.

From here, I went ahead and put everything together in a practical order, which I drew from my baking experience once again to do so. I started by creaming the sugar and butter by hand (since electric mixers may not have been used at the time, especially on an island in the north of Maine). I then added the rest of the wet ingredients to this mixture before slowly adding in the dry ingredients—flour, corn meal, cream of tartar and baking soda—and then letting the batter sit for about ten minutes. Lastly, I added the batter to a greased springform baking pan.

I baked the cake for about 35 minutes, starting with 15 minutes, checking it to find it still very raw, then continuing on with another twenty minutes. This time allowed for the cake to bake thoroughly, with the top coming out golden brown (Fig 2) and the bottom much darker, but not quite burnt. The edges were crispy and had some caramelization, but a little closer to burnt than the bottom reached. All in all, the cake had a good moisture level when consumed directly out of the oven and only dried out some overnight as tested by consuming another piece the following day.

The recipe proved to be successful thanks to my experience in baking and cooking. I am certain if I had not had this experience, reading through some of the other cake recipes in the book would have provided a good order of operations for mixing the ingredients, but I would have had to delve deeper into research for cooking temperatures and times.

One flaw I feel I made throughout this process was using a springform pan to back the cake. After a little research, I found that springform pans were first invented around 1919 by a German metal goods company known as Kaiser (Harte, 2023). With this information, it was definitely a historically inaccurate pan to use for this recipe, and something like a cast iron skillet would have been more accurate for the time. However, I didn’t think of this at the time.

All in all, the recipe turned out. I would call it good, and so might a few others that tried it, but some small improvements could make the cake more historically accurate if I tried this recipe, or another recipe from this book, again.

References:

Harte, Tom. (2023, Mar 27). A Harte Appetite: The Versatile Springform Pan. KRCU Public Radio. https://www.krcu.org/arts-culture/2023-03-27/a-harte-appetite-the-versatile-springform-pan. Accessed November 19, 2023.

Sutton Island (Maine) Cookbook, 1889-1897. B/S967. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/sch02223/catalog. Accessed November 19, 2023.

Student Work Wednesday- Featuring Celeste Femia

This week we're highlighting the work of Gastronomy student Celeste Femia. Celeste completed a project in which she recreated a historical recipe for the Cookbooks and History course taught by Karen Metheny here at Boston University's Metropolitan College.

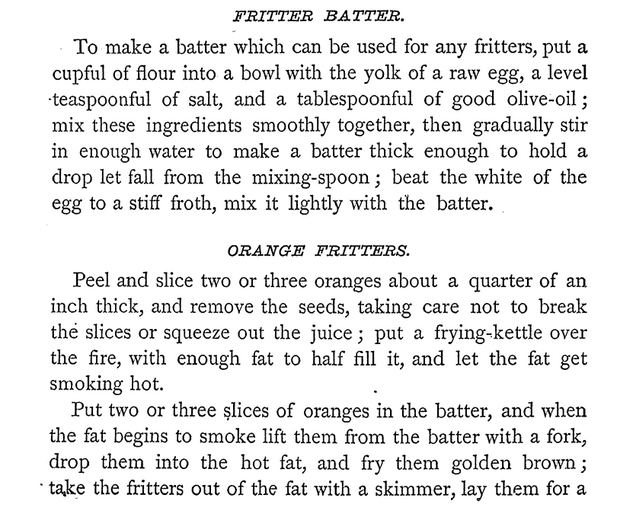

Recreating a 19th Century Orange Fritter

In my search to find a historical recipe for recreation, I stumbled upon a gem from the late 19th century, "Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery and Household Management" by Juliet Corson. Juliet Corson, an instructor, and superintendent at the New York Cooking School, collaborated with the Commissioner of Education to create this cookbook that went beyond regional boundaries. Published in 1885, this cookbook is a compilation of recipes contributed by locals from the Western and Southern regions of the United States.

Its diverse range of contributions piqued my interest, and I began combing through the recipes until one in particular, "Orange Fritters," caught my eye. The idea of slicing, battering, and deep-frying oranges was completely unfamiliar to me. I had never tasted an orange fritter before, so naturally, my curiosity got the better of me, and I was eager to discover both the visual appeal and flavor profile of this concoction.

Before diving straight into the recipe, I wanted to explore the origins of the fritter. A bit of online sleuthing unveiled that these delightful fried treats likely made their debut during the Roman Empire. In Italy, they are named not after their ingredients, but rather after the frying cooking method, known as "fritte." Additionally, early Italian cookbooks from the Middle Ages shed light on the distinctions between fritters fried in oil, ideal for religious days when animal products were forbidden, and those fried in lard, more suitable for everyday fare.

The world of fritters is a mixed bag of flavors and textures. Savory options, from fritto misto featuring meat, seafood, and vegetables dipped in batter and crisped up in olive oil, to the aromatic Indian pakora. In Japan, the batter-frying technique, introduced by the Portuguese and Spanish in the late 16th century, gave rise to tempura, which has become an integral part of Japanese cuisine. Sweet variations of fritters, including the French beignet and its counterparts, have also found their way across the globe.

To recreate the historical orange fritter recipe, I first needed to gather the ingredients: flour, an egg, salt, olive oil, water, oranges, powdered sugar, and oil for frying. Fortunately, these ingredients are readily available in today's markets, and I was pleased to find that most were already stocked in my cupboards.

The cooking process began with careful preparation. I assembled the ingredients and began crafting the batter. Following the instructions, I noted the need to beat the egg white into a stiff froth. Channeling the spirit of traditional methods, I separated the yolk from the egg white and began vigorously whisking. After about 10 minutes of continuous, wrist-burning effort, my egg whites achieved their desired stiffness.

In another bowl, I mixed one cup of flour, a teaspoon of salt, and a tablespoon of olive oil. The next step called for "enough water to make a batter thick enough to hold a drop let fall from the mixing spoon." Interpreting this as something like a pancake batter, I measured approximately one cup of water, incorporating it gradually while mixing. To assess consistency, intermittent checks were conducted to evaluate how well the batter adhered to a spoon. It took the entire cup of water to achieve what appeared to be the correct texture. Finally, I folded in my stiff egg whites.

With the batter ready, I turned my attention to heating the oil. The recipe called for using a "frying-kettle over the fire, with enough fat to half fill it and let the fat get smoking hot." I opted for a deep stainless-steel saucepan with canola oil due to its smaller diameter but greater depth, ideal for frying in small batches. The recipe's instruction to heat the fat until it is “smoking hot” terrified me! The thought of submerging a batter-coated, liquid-filled fruit into sizzling oil seemed like a potential recipe for disaster, with either scalding oil splatters on my arms or quickly burnt fritters. So, I opted for a temperature more in line with what I might use for frying chicken. To ease into it, I conducted a test round with one orange slice.

My initial attempt revealed some errors: first, some of the batter got left behind on the fork, leaving a section of the orange without any coating, resulting in a hollow space where the orange juice seeped out. Additionally, the oil was not hot enough. Learning from this, I increased the heat and made sure to subsequently stab the orange with a fork, thoroughly coating the slice in batter, and then immersing it into the hot oil. This method proved much more effective; all sides of the orange were evenly coated, and the slices were frying up beautifully. Working in small batches of two at a time, I battered and fried the rest of my slices. Each orange slice was laid on paper towels to drain and then dusted with a generous layer of powdered sugar.

So, how did they taste? I will be honest, my orange was not the sweetest, and in hindsight, I wish I had sampled a slice first to gauge the flavor profile before diving into the frying process. A hint of bitterness lingered, likely a result of my less-than-sweet orange combined with the olive oil in the batter. Given that the batter itself lacked sugar, the fritter's sweetness relied heavily on the powdered sugar on top. Despite this, they turned out surprisingly good.

Reflecting on this experience, if I were to recreate these orange fritters again, I'd consider adding sugar, testing the orange beforehand to ensure optimal sweetness, and I would use lard for frying, as it might enhance the overall flavor profile and possibly result in a more delicious fritter.

References:

Corson, Juliet. 1885. Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery and Household Management.

New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/58.

Encyclopedia Britannica. 2021. Fritter. Date of access, November 15, 2023.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/fritter.

Montanari, Massimo. 2012. Let the Meatballs Rest: And Other Stories About Food and Culture.

Columbia University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bu/detail.action?docID=1028072.

Rachman, Anne-Marie. 2023. Corson, Juliet, 1842-1897. MSU Libraries Digital Repository.

Date of access, October 20, 2023. https://d.lib.msu.edu/msul:63.