Anthropology of Food: A Selection of Final Projects

Food Mapping: Revealing the Unseen

Written by Sarit Sadras Rubenstein for Anthropology of Food

“Food mapping is an image-based approach to research that pays attention to the way people relate to food in the interaction of senses, emotions, and environments” (Marte 2007).

Food mapping is an interesting assignment students take during “Anthropology of Food” class. Food Mapping is a tool, that even though it is relatively simple to apply, reveals many interesting things, much of which would not be revealed otherwise.

For my mapping assignment place I chose a local Target store, one that I know pretty well. That specific store has a Target-cafe corner with two vendors: Starbucks and Pizza Hut. Every time I bought coffee at Starbucks I always wondered if and when people buy at the Pizza Hut place. It always seemed empty… That is why when we had the chance to observe a place and map it, I chose to observe this specific cafe corner. In my observation I was hoping to learn more about how people interact at this specific cafe corner, in relation to the two vendors, the environment and to other people in general.

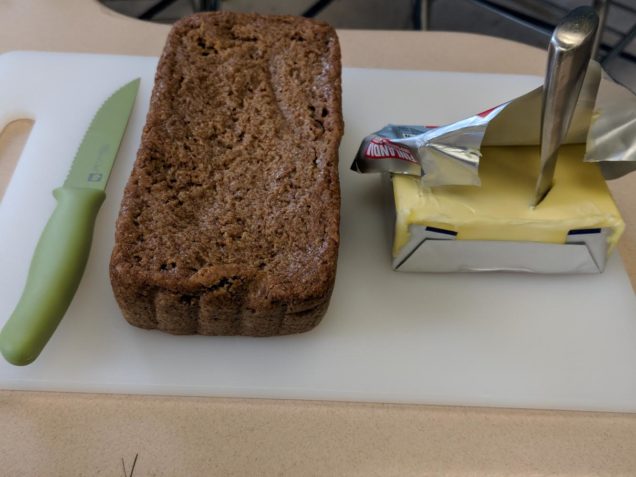

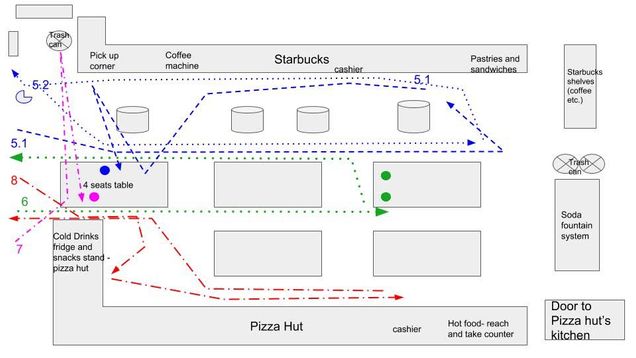

It is good to start with a description of the area being mapped. Examples of such description can include where each vendor is located, how many sitting tables are there, what colors are being used as decorations, and anything that can help the researcher get familiar with the space. In my specific observation the cafe shop is located at the edge of the store, as with most of Target’s cafes, where one can walk in and go straight to the cafe without walking through the aisles. Facing the cafe space, Starbucks is placed on the left side and Pizza Hut on the right (see a map and pictures attached). Overall I would argue the environment is not as inviting as it could have been. The tables and chairs are made of metal, giving a ’cold’ and unpleasant look and feeling. It seems as it matches the decor of the Pizza Hut spot more than it fits the Starbucks one.

For the process of the observing, I arrived at the cafe around 10:45 am. I chose the table that is furthest away from the entry, which gave me a great view of the whole cafe space. I started to map the cafe area, making three copies so I would have extra copies in case I needed it. By the time I finished, it was almost 11:15, the tables were available and no people at either the coffee or the pizza lines. That didn’t last too long though, since at that very minute new customers started to show up, so I started my observation. All the people interactions I observed that morning were detailed by the order they arrived to the cafe, and were drawn on the maps I have created, as you can see at the example attached.

Once the observation is done, the interesting part starts: analyzing the data and see what can we learn from that exercise. Some conclusions from my observation were quite surprising. For example, the vast majority of the customers were women, unaccompanied. During my observation I noticed only three men, out of which only one actually bought a drink at Starbucks. All the other customers were women. This is a very interesting observation. It is worth investing more time and other observations during other days and times of the day. If this is a repeating phenomenon it can be used as a great marketing tool to the cafe and Starbucks.

Another interesting conclusion I noticed was regarding the shopping carts. I can definitely argue that there is a shopping cart parking problem while buying at the cafe. There is no organized and defined place to park shopping carts while waiting. This situation results in people blocking the line (mostly the line for Starbucks) or placing their carts in other people's way. I think it is worth investing more time and think of a creative idea to reorganize the space in order to improve this issue. These are just two single examples out of few conclusions this observation taught me

about that specific environment and the people who attend it.

One of my findings was regarding the number of tables and sitting spots at the cafe. It seems as if the number of tables is suitable for the amount of customers who choose to sit down at the cafe. That said, this note needs to be observed again, especially during times when families shop with there kids and might need more space to sit down and have a short snack break. In such times there may be shortage in tables or chairs. Also, there is a point to argue what would be the outcome if the cafe looked a little more inviting? Would this lead to people hanging out more? In a such a scenario, would the number of tables and chair suffice the location or would it need to be adjusted?

Obviously some of the questions that arise from this exercise are very interesting but still theoretical. To answer such questions, more research and observations needs to be done. Such research will probably take us outside of the academic world, since it will have to take into account the goals and objectives the organization, Target in this case, defines for itself.

As Marte (2007) claims, food maps are useful not only for food studies, but also for other kinds of research. I can surely see how food maps can come handy for such organizations as a marketing tool and a strategic tool. I wonder if and to what extent big organizations, such as Target, use such tools, as food mapping, to learn and streamline their customers’ experience.

References:

Marte, Lidia. 2007. Foodmaps: Tracing Boundaries of “Home” Through Food Relations. Food & Foodways 15(3-4): 261-289.

What is America Food?

Written by Olga Rizhevsky for MET ML 641, Anthropology of Food

When discussing ‘American Food’, it seems one of two main schools of thought is prevalent: either the clear understanding that burgers, pizza, and apple pie are emblematic of the country; or that we live in a nation with mixed cuisine from all over the world, and we create our own by borrowing from abroad. Extremists might argue there is no such thing as American food all together. Why did our cuisine become to hard to define, and is that a problem? A brief consideration of a few topics below further explores this inquiry.

The Great American Menu, Ranking Regional Foods Across the U.S.

For one, America as a country has long cultivated staple crops such as corn, soybeans, and cotton- plus a whole ton of cattle. Consolidation via industrialization of farming land and operations has increased the popularity of these foods, often at the expense of non-monoculture crops cultivated on small family farms; the biggest support of this phenomena has been through formal government subsidies. However, how often do you actually see someone consuming plain corn (whose authenticity is infact Mexican) or soybeans, perhaps in the form of tofu? The reality is that corn and soy are often ingredients in other foods, typically ones that have been processed, artificially sweetened, and would be considered ‘junk food’ by most. We are beginning to see label-conscious consumers strive to better understand what’s in their food, and many are going beyond to be educated on its origins.

Second, an emerging ‘foodie’ movement, particularly in urban areas including Boston, has lent itself to an overwhelming focus on foods that are interesting and picturesque- an attitude of discovery implying sophistication. To each their own with the definition of a foodie, but given its apparent over-use, it begs the question as to whether or not everyone is a foodie (in other words, a lover and/or consumer of food?). On this topic, in a 2014 NYT article, Mark Bittman challenges the term by advocating that it should pivot more toward those who are conscious in their food consumption, rather than just find joy in it; “it might be useful to sketch out what “caring about good food” means, and to try to move “foodie” to a place where it refers to someone who gets beyond fun to pay attention to how food is produced and the impact it has.”[i]

Third, the politics of food in the US leave consumers with much to ponder, which is constantly changing. A generally confusing climate in regard to policy, nutrition, and environmental implications is ever-growing. We are consumers and producers of foods that are internationally traded, at times when NAFTA and immigration-reform are heavily under scrutiny. We shift from loathing carbs, to fat, to sugar, at a time when obesity rates are on the rise. Perhaps conflicts within one’s ‘food identity’, compromising self-expression, are an extension of broader confusion regarding what is authentic American food.

Despite lack of consensus, building awareness regarding ‘what is American food’ is in itself enlightening. Consider the eateries that surround BU (Chinese, Thai, Indian) in the proximity of quintessential Fenway Park—or Quincy Market across the street from the North End. Also consider the cravings you have when seeking ‘ethnic’ food (perhaps another ambiguous term to define). Living in a nation so populated by immigrant traditions and influences, it surely is a challenge to identify with a single defining cuisine.

[i] Mark Bittman, “Rethinking the Word ‘Foodie’.” June 24, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/25/opinion/mark-bittman-rethinking-the-word-foodie.html

UNESCO: Protecting Cultural Heritages Worldwide

Written by Sarah Faith

If you’ve ever been to France, then you know that a baguette from a boulangerie in Paris, Lyon, or Provence has an air of je ne sais quoi about it. More than four hundred years of practice - and a revolution - have gone into the making of the iconic French baguette. It is a staple food, a part of daily French life - morning, midday and in the evening. A veritable symbol of the country.

The traditional baguette is protected under a 1993 French law. To truly be considered a “traditional French baguette,” the bread must be made on the premises from which it is sold, it must be made with four ingredients only (wheat flour, water, yeast and salt), it cannot be frozen at any stage, and it cannot contain additives or preservatives. Making a traditional baguette requires more than the ability to follow a recipe. It requires practiced skill.

However, times are changing. Many French are no longer eating baguette three times a day as eating patterns change. Fewer bakeries are making baguettes in the traditional manner, often relying on frozen bread in an effort to cut costs.

Now, in an effort to protect the quality of and skill that goes into the making of the baguette, President Emmanuel Macron is supporting a bid by the National Confederation of French Bakers. Their goal is protection of the baguette as a “world treasure” by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Established in 2008, the UNESCO Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage include oral traditions, social practices, performing arts, festive events, rituals, knowledge/practices concerning nature, and knowledge/skills to produce traditional crafts that are recognized by communities around the world as being representative of their cultural heritage. The items on the lists are passed down from generation to generation. They provide a sense of identity and community.

UNESCO has inscribed heritages from around the world, including Uilleann piping (Ireland), the Tahteeb stick game (Egypt), and the Yama, Hoko, and Yatai float festivals (Japan). These heritages help to nourish both cultural diversity and human creativity and, according to UNESCO, “can help to meet many contemporary challenges of sustainable development such as social cohesion, education, food security, health and sustainable management of natural resources.” In granting the list designation, UNESCO aims to ensure that intangible cultural heritages worldwide are better protected and awareness of them promoted.

As of this writing, there are 470 items corresponding to 117 countries on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage lists. And food plays a role, with a number of cultural foods, cuisines and practices represented. Curious to learn more, I dug a little deeper. Below you’ll find a snapshot of my food-related findings - one from each of the ten years that the lists have been in existence.

2008: Indigenous festivity dedicated to the dead (Mexico)

2009: Oku-noto no Aenokoto (Japan)

2010: Gastronomic meal of the French

2011: Ceremonial Keşkek tradition (Turkey)

2012: Cherry festival in Sefrou (Morocco)

2013: Kimjang, making and sharing kimchi in the Republic of Korea

2015: Arabic coffee, a symbol of generosity (United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar)

2016: Beer Culture in Belgium

2017: The Art of Neapolitan ‘Pizzaiuolo’ (Italy)

As for whether the French baguette will be given the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage designation, we will have to wait and see. After the National Confederation of French Bakers submits its nomination, they must then wait for the annual meeting of the Committee for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. During this meeting, the Committee will evaluate this and other nominations and decide whether or not to inscribe the French baguette to the lists for safeguarding.

For more information about the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage lists visit https://ich.unesco.org/.

Sarah Faith is a student in the Gastronomy program and marketing and communications professional specializing in food and agricultural at CONE in Boston.

The Circus of the Senses: A Symposium on Food & the Humanities

Article and images by Ariana Gunderson

The Culinary Institute of America hosted the Circus of the Senses: A Symposium on Food & the Humanities this past Monday, a feast for both mind and tongue. The day-long symposium demonstrated the best of CIA’s Applied Food Studies program, combining traditional academic papers, collaborative discussion, and a surrealist banquet inspired by Salvador Dalí. Here I’ll share my experience and thoughts on the symposium.

Upon arrival at CIA’s immaculate campus, symposium attendees were served a light breakfast; I was quickly learning that at the Culinary Institute of America, food is the starting point. The conference got started with two sessions of roundtables, in which conference attendees signed up for small discussion groups. The leader or leaders of each roundtable presented some of their work or media to which the group would then respond in discussion. I attended and very much enjoyed “Tracing and Tasting Aromatic Images in Cinema,” a roundtable led by Dr. Sophia Siddique Harvey, of Vassar’s Film Department. Dr. Harvey shared a short film clip and her concept of an ‘aromatic image’ – when the audiovisual medium of film evokes the proximal senses. Our lively group discussion was shaped by the contributions of a food stylist, whose career is centered around the creation of such images, and academics from French, Philosophy, Creative Writing, and Food Studies departments. By starting the symposium with a discussion to which all attendees contribute, I felt invigorated and directly participatory in the rest of the day. Following a lunch break at any of CIA’s many student-staffed restaurants, the afternoon consisted of two traditional academic panels. All presentations covered food and the senses (very relevant to the BU community!) but from a wide range of disciplines. Chef Jonathan Zearfoss presented on Patterns in Tasting Menu Design, Dr. Yael Raviv of NYU spoke about food as a medium in avant-garde art, and Dr. Greg de S. Maurice gave a talk on multisensory taste and national identity in Japan.

Following a lunch break at any of CIA’s many student-staffed restaurants, the afternoon consisted of two traditional academic panels. All presentations covered food and the senses (very relevant to the BU community!) but from a wide range of disciplines. Chef Jonathan Zearfoss presented on Patterns in Tasting Menu Design, Dr. Yael Raviv of NYU spoke about food as a medium in avant-garde art, and Dr. Greg de S. Maurice gave a talk on multisensory taste and national identity in Japan.

My favorite paper was presented by Dr. Andrew Donnelly of Loyola University’s history department, “Re-experiencing Rome: The “Next” Apicius.” Dr. Donnelly spoke with humor and rich historical background on the ancient Roman diet and its reincarnation at a Chicago tasting menu, describing how in just one dinner his academic understanding of Roman history had been made sensorially experiential. Ted Russin, the acting Dean of the School of Culinary Science & Nutrition at CIA and flavor scientist, gave punchy closing remarks in which he presented on the interconnectedness of sensorial experience in eating.

Attendees were able to immediately put Dean Russin’s presentation into practice in the final event of the symposium: the Circus of Taste, a banquet inspired by the surrealist work of Salvador Dalí and brought to vivid life by the students and faculty of the CIA. We kicked off the feast with 59 minutes of cocktails – guests swizzled their own signature cocktail of snow, ginger, shiso, and fresno chili and nibbled on passed hors d’oeuvres as a large clock ticked away the minutes and swirling lights brought plastic lobsters in and out of focus. As I stood at a table with a centerpiece of apples in a basket (each apple bearing a fake Dalí mustache), I accepted round after round of such surreal delicacies as deviled quail egg, rosé gelée with caviar, savory cheesecake with strawberry pearl boba, and spicy avocado mousse on puff pastry. Once the 59 minutes (exactly) had passed, we moved into the dining hall, spritzed with a Dalí perfume as we did so.

Once again, the dining hall was sensorially overwhelming. This feast was a celebration of Dalí’s work and especially the cookbook he wrote to memorialize the lavish dinner parties he hosted with his wife, Gala. Recreations of Dalí’s artwork filled each corner of the room, and Un Chien Andalou played on three walls. Each seat had a placemat of a different material: tin foil, fur, bubble wrap, sandpaper. Spread down the winding table were musical instruments; guests were instructed to play different instruments when they experienced different tastes. Crawfish in consommé, the first course, was the most impactful for my sensory experience. Dalí’s love for crawfish resulted in several recipes boasting the crustacean in his cookbook, Les Diner de Gala, including a memorable Tower of Crawfish.

In our first course bowls, a whole crawfish swam in soup, to be cracked by the diner. This was my first time eating a crustacean, and the sensorial impact of cracking open the exo-skeleton was quite powerful. Roquefort Pasta and Hanging Beef (accompanied by paired wines) followed, and the atmosphere in the room rose to a festive pitch as guests donned food fascinators and shook the noisemakers. My tablemate remarked, “it’s like a really weird wedding,” in which the couple we were celebrating was Gala and Salvador. The final course, a dessert, was called BEETING Heart – a beet mousse, molded into a heart-shaped beet drawn from the earth (represented by crushed cookies and chocolate sorbet). Walking the halls of the CIA, I had seen the students preparing various parts of these dishes, and I was blown away by the impression they left in the context of the banquet. The final touch on the evening was the after-dinner coffee – delivered via espresso bubbles.

This symposium brought together what excites me most about the field of Food Studies. The range of activities throughout the day demonstrate the multiple forms food scholarship can take: collaborative discussion, panel presentations, and creating and consuming food itself. The community of rigorously interdisciplinary food scholars represents the breadth and richness of food studies. I anxiously await the next symposium hosted by the masterful team at the Culinary Institute of America.

Course Spotlight: Food & Visual Culture

Images, whether still or moving, are all around us and have become an increasing part of the modern landscape. The result of this proliferation of visual culture is that our understanding of the world is progressively mediated by images. So, not only have the products of visual media become more and more a part of our lives, but vision and seeing have become even more important to how we know and understand the world. But the visual does more than simply present the world to us, it can shape how we understand and relate to that world. Studying media, therefore, is a way for us to study ourselves and better understand our culture, our social and political values and our ideologies.

Within the past decade there has been a notable growth in food-related cultural activity on TV, in films, books and digital media (Twitter, websites, blogs, video games, etc.). Food has become, both figuratively and quite literally, more visible in our lives. But what is behind this increased focus on food? And, how has it affected people’s expectations around how food is produced and eaten? What affect, if any, has it had on the way we eat and cook?

Within the past decade there has been a notable growth in food-related cultural activity on TV, in films, books and digital media (Twitter, websites, blogs, video games, etc.). Food has become, both figuratively and quite literally, more visible in our lives. But what is behind this increased focus on food? And, how has it affected people’s expectations around how food is produced and eaten? What affect, if any, has it had on the way we eat and cook?

The goal of this course is to examine depictions of food and cooking within visual culture and to analyze the ways in which they reflect and shape our understanding of the meaning of food. To this end, we will explore how food and cooking are depicted as expressions of culture, politics and group or personal identity via a multitude of visual materials, including, but not limited to: TV programs, magazines, cook books, food packaging, advertising, photography, online and digital media, and works of art.

A good portion of class time will be given to discussing the readings in combination with participatory, in-depth analysis of the visual material. The class will also take a field trip to a food photography studio as well as a culinary tour of Boston's Chinatown.

A good portion of class time will be given to discussing the readings in combination with participatory, in-depth analysis of the visual material. The class will also take a field trip to a food photography studio as well as a culinary tour of Boston's Chinatown.

MET ML 671, Food and Visual Culture, will be offered during Summer Term 1 (May 22 to June 29, 2018) and will meet on Mondays and Wednesdays from 5:30 to 9:00 PM. Registration information can be found here.

Celebrate Pi(e) Day with Boston Cream Pie!

On Wednesday, March 14, the Public Library of Brookline at Coolidge Corner will be hosting an event in celebration of Pi(e) Day, highlighting none other than New England’s Boston Cream Pie!

Join Justine, Adrian, and Mashfiq, three BU Gastronomy students, from 4:30-6:00 p.m. at 31 Pleasant Street in Brookline as they talk about the history and origin of this famous New England dessert and walk us through how it has changed and evolved through the decades. Come prepared to sample a few from local eateries! See below for more details.

Pi Day Celebration

A Brookline Eats! series event

Boston Cream Pie. Massachusetts’s state dessert. Not a pie at all, in fact, but two light-as-air sponge cake layers sandwiching a rich and delicate pastry cream, and topped with a thin glaze of chocolate. When made properly, the dessert seems to defy all laws of gravity.

As the story goes, the simultaneously simple and decadent cake was invented by a chef from Parker House Restaurant in Boston, Massachusetts in preparation for the restaurant’s 1856 grand opening. True of nearly every food-related origin story, there is much debate surrounding the question: where did the Boston Cream Pie come from? No matter which story you believe, it is hard to argue the Boston Cream Pie’s position as a quintessential New England dessert. Over the years, it has inspired a seemingly endless number of variations from donuts to an ice cream flavor to a local spin on beer. It’s easy to see that the Boston Cream Pie has come a long way since its debut.

Food and the Senses: Taste and Flavor Podcast

Image courtesy of maximumyield.com.

Frank Carrieri and Morgan Mannino were tasked with presenting on the topic of taste and flavor for Professor Metheny's Food and the Senses course. Instead of doing a video presentation, the two decided to create a podcast. This format allowed them to incorporate sound bites from interviews as well as have a conversational approach to the subject matter.

The casual conversation and interviews helped them convey the complex ideas in a simplified form that others could easily digest, one of their goals for the project. They also used this approach to get others to think about how they experience flavor and taste when they eat and cook.

Works Cited

Birnbaum, Molly. February 14, 2018. Interview by Morgan Mannino. Personal Interview. Boston, MA

Johnson, Carolyn. February 17, 2018. Interview by Frank Carrieri. Personal Interview. Boston, MA

McQuaid, John. 2015. Tasty: The Art and Science of What We Eat. chs 1-4 . New York: Scribner.

Shepherd, Gordon M. 2012. Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters. Intro, chs 1-4, 13. New York: Columbia University Press.

Being Boston’s Brunch Guide

Written by Alex DiSchino. Photos by @BostonBrunchGuide.

As anyone with an Instagram can tell you, there are A LOT of people posting about food. Any Joe or Jane with a camera phone can easily fancy themselves an amateur food critic slash photojournalist slash influencer and reach their friends iPhones with just a few taps of a touchscreen... but there are a surprisingly few amount of people who get any REAL traction...rising above the ranks to become elevated to the status of influencers.

So while restaurateurs everywhere are constantly being pushed to step up their game so every plate that leaves the kitchen is perfectly cooked for every diner, they are also presented with a new challenge: make sure that each plate is camera ready! After all, it’s destined to be immortalized on the internet as Instagrammers across America aim to make their followers salivate.

With that said, the Cambridge Dictionary defines an influencer as "someone who affects or changes the way that other people behave, for example through their use of social media."

I had the pleasure of spending a behind the scenes day with local Boston food instagrammer @BostonBrunchGuide to learn a little more about she gets people off the couch and into restaurants through the magic of social media. And while the day started as an ordinary Q&A over coffee, what came next really surprised me….

First, let’s meet Danielle:

@BostonBrunchGuide has seen amazing growth - Danielle was telling me that she’s grown from a little over 3000 to almost 9000 followers in the past 12 months, earning about 15 new followers a day on average.

Q: Tell me about yourself: Where you from, what brought you to Boston and what do you do when you're not eating brunch?

A: I’m originally from Connecticut but have lived in Boston for almost 10 years. I moved here to attend Northeastern University and ended up staying after graduation. While I wish I could survive off brunching alone, I actually work full time in finance.

Q: So when did you start @BostonBrunchGuide?

A: Fall or winter of 2014, but it wasn't until the past year that I really became serious about it.

Q: What made you want to start a food instagram?

A: I wanted to start some sort of blog, I tried a couple other topics but when I started talking about food it stuck. Food is such a big part of my everyday, so it just came naturally.

Q: So why brunch?

A: It is hands down the best meal of the week. There are no rules. It allows chefs to be creative with menus and it's the perfect time to catch up with friends. Who doesn’t want to go to brunch??

Q: What’s your favorite brunch item?

A: Eggs Benny. There are so many expressions. I am also a big fan of the new “table cake” trend which lets you get a bit of sweetness into the meal without committing fully.

Q: Umm...table cake?

A: Yep, like a super decadent pancake or waffle to share. For example, Lincoln Tavern in Southie serves a Fruity Pebbles Pancake. It’s not great for a full meal, but perfect to share.

Q: Awesome! Ok, now a harder question. Is there an expectation that your posts will be positive when a restaurant invites you to dine?

A: When I am invited into a restaurant, the expectation is definitely that I will post a photo of my experience-- but I always note that I will only post if I truly like what I’ve tried. If I don’t like it, I won’t post it. I choose to focus on highlighting the positive experiences I’ve had. I’m not a food critic. With all the sponsored content on social media these days people don’t know what is real and that’s a big issue. If I post it, I truly liked it. If a restaurant has a problem with that, I’ll say thanks for the offer turn down the invite. Luckily, not many have.

Q: I can get behind that. Okay, a few more questions. What do you feel the most challenging aspect of starting @BostonBrunchGuide was?

A: The number one thing for me was patience. Some weeks can be really frustrating, when you’re producing content and getting less engagement than you thought you would. There are so many new instagram accounts just getting started out there that ask “How do you get invited to these events?” or “How do you get free food?” There is an oversaturation of Boston food instagrams out there -- and if you’re only in it for the free food, it is going to be hard, frustrating, and you probably won’t find much success. You have to be patient and build an audience that believes in what you're doing and saying, and you have to be honest about it. Don’t get me wrong, the perks are amazing and I truly feel so lucky to be doing this, but it isn’t why I started BBG.

Q: And now that you have that audience, I noticed you recently launched a website and a blog, what sparked the expansion?

A: Instagram is such a visual platform. I was posting a lot and getting a lot of questions that I wanted to answer. “I’m coming in town for the weekend, where should I get brunch?” was a popular one. I wanted a place where I could engage with people away from Instagram and provide more content. After all, Instagram could go away any day with the way trends in social media work.

Q: Smart move. Okay, so last question - what are your goals for this year coming off a year of really great growth?

A: I’ve really had to start thinking about this hobby a lot more like a business. The more I’m engaging directly with restaurants rather than just going in and dining myself, the more I feel that I need a real brand, logo, etc. I also really want to expand the website to have a real “Brunch Guide.”

Q: Really great. I’m sure all of your followers will be excited for that. So where are you off to after this?

A: I was actually invited to Towne for brunch along with another instagrammer (Joey from @the_roamingfoodie)…wanna tag along?

I had no idea what I was in for!

We walked into Towne Stove and Spirits at 11 am on Saturday. They had just changed the brunch menu and had invited Danielle and Joey to come dine. The chef was so excited he decided to plan a little surprise. We were escorted upstairs into a private dining room and greeted by the Chef.

NOTE: Both Joey and Danielle noted that the following events never happen, so I guess I picked a great day to tag along.

Normally, Danielle sits at a table, orders her food, takes as many pictures as possible before it gets too cold. She scarfs it down hurriedly while editing a post and finishes just in time for the next dish. Today, she ate first...then was offered the whole menu.

What I originally expected to be a quick brunch became a truly remarkable afternoon. The head chef paraded new item after new item for the two to shoot and taste. My personal favorite was the waffles.

While the passive follower might be enamored by the fact that these two influencers got to try all this food for free “just for posting some pictures,” I got a chance to the see the real reason restaurants entertain from an outsider's perspective.

Over the 3 hour escapade, Danielle provided an invaluable resource to the restaurant - not only by taking pictures of delicious food, but also by brainstorming new marketing ideas, educating the chef and manager on their consumers, and making approximately 9000 potential Boston local new diners crave a big stack of chicken and waffles. I have to say that’s certainly not a bad deal for Towne and really reinforced why we should absolutely expect to see big things from influencer marketers and @BostonBrunchGuide in the future.

Eating Food, Talking Memory & Talking Food, Eating Memory: A Nostalgia Dinner Reflection

Written by Ariana Gunderson. All Photographs by Alexander Rogala.

The doorbell rings, announcing the first guest’s arrival. One by one, the five guests climb the steps, take off their coats, and meet a small group of strangers. One person lays out a casserole dish, one 6 cans of soda on the side table. A few pots are warmed on the stove. Once all the dishes are ready, we grab our plates, take a bit of everything, and sit down to start our Nostalgia Dinner.

Nostalgia Dinners, participatory research events studying food memory, began as part of my Introduction to Gastronomy: Theory and Methodology course, taught by Dr. Megan Elias. The Nostalgia Dinner Series has now grown into a collaborative research project, in which every guest shares their lived experience as data and becomes a co-investigator.

A Nostalgia Dinner takes place on one night in one apartment living room, but the food and conversation traverse time and place, spanning continents and decades. At these dinners, each guest brings a dish that evokes ‘nostalgia’ for them, sharing tastes and taste memories with the group. As we eat, we hear the stories behind the food and learn why each guest chose their dish for the dinner. We draw connections between the dishes and memories brought to this event, wrestle with concepts and definitions of nostalgia, and peel back the emotional layers of food memory.

Because every Nostalgia Dinner has a different menu and guest list, the discussion is never the same twice. At one February 2018 nostalgia dinner, lamb curry led to a discussion on coming to terms with the exploitation of gendered foodwork in one’s own family history, and ‘Mom’s Soup’ sparked talk on the renegotiation of family dinner when one moves back home in one’s twenties. Rice Krispies revealed the taste of a specific place (Boston Logan Airport, upon returning from a long journey) and Guaraná soda the taste of specific time in the past (early childhood spent in Brazil). A now-vegan guest’s mushroom version of her father’s beef stroganoff brought into stark relief the inaccessibility of the past. Her taste memories connect her to those dinners of middle school weekdays, but her age, changing diet, and life in a new city make clear how impossible it is to truly recreate a meal of the past. The next Nostalgia Dinner will cover different intellectual territory, shaped by its unique configuration of dishes and participants.

In studying food and memory, I try to choose methodologies that honor the knowledge and lived experience carried within each person. I believe this topic, tangibly relevant to everyone who has ever eaten (or not eaten) and remembered it, can be best explored collectively. In my Nostalgia Dinner Series, I learn from my guests about their experience with and memories of food, just as I hope this experience will encourage them to think about food and memory in new ways.

If you are interested in attending a Nostalgia Dinner this spring, please email Ariana at arianag@bu.edu.