The Hickory Nut Adventures

Current student Neema Syovata describes the research process for her Introduction to Gastronomy final project.

THE HICKORY NUT ADVENTURES

This all began with a simple question – why aren’t there more opportunities to experience Native American food? And so, for my introduction to gastronomy final project, I opted to create a menu of contemporary Native American cuisine. My research would require me to understand what was happening with Indigenous foodways pre and post contact.

The Institute of American Indian Studies in Washington, CT has a research department complete with an extensive library. On my first visit, I explained my project and was delighted to find several shelves containing culinary materials. Furthermore, everyone I encountered there was extremely helpful in offering their perspective or pointing me towards a resource that would be useful. Should you ever run into the research director Lucianne Lavin, you are in for a treat! She is captivating and an archeological authority. I quite literally conversed with her for 3 HOURS… All I can say, is that it was time well spent because it provided me with a good historical background on Native Americans.

In my research, I read about hickory nuts, and wondered where I might find some and why they were not commercially available. By the time I was discovering this information, we were late in the season for picking hickory nuts. In a rather serendipitous moment, I discovered that my neighbor had hickory trees, shagbarks to be specific (which are the ones you want to eat). I was beside myself with joy but it was short-lived. You see the reason that hickory nuts don’t exist commercially is because they are labor intensive. LABOR INTENSIVE (that is definitely me shouting)!

I spent a whole day engaged in labor in what would have been a communal activity in Indigenous communities. Neema party of one vs the hickory nuts. The first step was shelling the nuts from their green exterior, that took a “minute.” Then came the sorting and the third step was a rather ingenious one (not on my part). Native Americans would soak the nuts for two reasons, the first to be rid of all the hickory nuts that rose to the top (these were no good, I tested this theory and found some critter living inside one, gag), and the second was to soften the nuts to make it easier to crack them. I did not do the long soak because I put them in the oven to dry them first, and then roast them. What followed was a therapeutic session with a mallet and a kitchen towel which resulted in a handful of nuts, or said another way enough for 2 servings. (Click link to see the process) I went to sleep off my disappointment.

The next day, I woke up thinking of the many ways I could use hickory nuts and perhaps if I could find a better way to crack the nuts so they could maintain their shape – maybe next season (late summer, early autumn I’m told). I then used the “handful” of hickory nuts to create a cream sauce to go with salmon, topped with a scoop of mashed potatoes, garnished with fried sage and cremini crisps. All are ingredients that indigenous people would have eaten, but with a modern twist.

A Day in Back Bay

This guest post comes from current student and president of the Gastronomy Student Association Payal Parikh. Are you curious about what Gastronomy students like to do in their day off? Looking for Gastronaut-approved activities in Boston? Read on!

A few weeks ago, fellow Gastronauts, Sarah Critchley, Sarah Hartwig, Neema Syovata, and I set out on a day of fun in Boston. As new-ish Bostonians we thought it would be nice to explore our town. If you ever need a fun, yet educational day of fun in Boston, here is your path, feel free to mix and match as you may see fit.

We started out the day with bagels from the new and popular Medford spot, Goldilox Bagels. The bagels are definitely in the running for best bagels in the area. We enjoyed them on the steps of the Museum of Fine Art, or the “MFA,” as the locals call it. Boston University students get in for free so it was nice to go in and see as much as we wanted without the pressure of seeing the whole museum in a day, and one could easily spend the whole day there if given the opportunity.

We started with the new exhibit about Ancient Nubia and played a fun game to see who could find the first piece of “gastronomy” related art, there was a toss-up between an ancient dining room set and a watermelon necklace, but in the end, we decided no winner was to be had and continued the search. We then wandered over to the Women and Art exhibit where we were greeted with a stumper of a question – could we name five women artists…it took a bit but the collective group was able to do it! We were all a little embarrassed with the time it took to do so. It was in this exhibit that we came across a wonderful painting of cabbages, that was the clear gastronomical winner!

It was at that point we decided it was time for lunch, we walked from the Fenway/Kenmore section over to Back Bay with our eyes on Saltie Girl. The seafood restaurant known for its large selection of tinned fish was at an hour wait for our party so we put our name in and decided to move on. Sticking with the newly decided theme, we walked over to The Salty Pig, which we were able to sit at right away. We shared some pizza and salads while taking in the neighborhood sites, as it is situated on the corner of a little shopping plaza. During this time, we also received a call back from Saltie Girl saying our table was ready. Even though half the group had to leave to go back to their regularly scheduled day, Sarah C and I soldiered on and decided to have a second lunch. Walking through Back Bay was very enjoyable at that time of day and we soon arrived back at the bar at Saltie Girl. We ordered a couple of small, delicious plates and I also had a daytime glass of wine (it was a mini-vacation after all). The wine was good and reasonably priced but the real excitement came from the glass it was served in, a small tumbler, which was out of character for a $$$ restaurant, instead of a seafood shack.

After closing out, Sarah had to head to work and I was on my own for an hour. I walked over to the Boston Public Library to check it out as I had never successfully been inside of it. It was as beautiful as all the pictures I had seen. It was surprisingly busy with tourists taking pictures instead of people looking for reading material. I had an enjoyable time perusing the shelves and walking through the courtyard in the slightly chilly October day.

For the evening, fellow Gastronaut Kate Cherven met up with me at Eataly for some Italian food perusing. After a riveting discussion of canned truffles and a self-directed dried fruit tasting with an employee, we sat down for some much-needed espresso and planned our next move. Kate’s husband Stefan met up with us and we went over to a nearby bar that had been on a dive bar list of the area. The original Bukowski’s Tavern, inspired by Charles himself, where they don’t serve Bud Light and the chalkboard is full of funny quotes from Yelp! reviews. After finding out we missed trivia, we hung around for a bit, had some beverages, and snacks and decided more future visits were in order. We ended the night at a little Vietnamese place nearby, the name was forgettable but the soup was good and we all made it home before the rain came down. It was a wonderful Back Bay day indeed.

Recreating Pound Cake from Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery

This guest post is part of a series written by students from Karen Metheny's Cookbooks and History course. Jie Liu shares her thoughts on recreating this historical recipe for pound cake, and includes a video of her process.

Recreating a Historical Recipe: American Cookery – Pound Cake

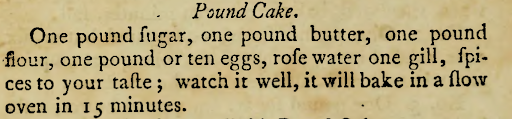

In the Cookbooks and History class, we’ve analyzed many old cookbooks. One of the old cookbooks that I am really interested in is American Cookery from Amelia Simmons, the first American cookbook, which was published in 1796. This book became the first choice for me to choose the recipe to do my “Recreating a Historical Recipe” assignment. Fortunately, Simmons’s recipes are based on very simple ingredients, nothing too exotic. But most of Simmons’s recipes are lack of detailed procedures. Pound Cake is one of the shortest recipes in the book. As you can see in the recipe, it only calls for sugar, butter, flour, eggs, rose water and spices. The pound cake was favored in old time because its ingredients are so simple to remember. The original pound cake, without other ingredient, only contained one pound each of butter, sugar, eggs and flour. But in Simmons’s recipe, she adds rose water and spices to enrich the flavor of the cake.

In American Cookery, the majority of the sweet recipes used rose water, but I’ve never had a bottle of rose water in my kitchen. So, I went to one of the biggest supermarkets near my house and asked two market mangers to help me find rose water. They were both surprised that I was looking for rose water for baking purposes. One of the mangers said, “I’ve never heard of that—using rose water in baking.” It seems rose water is no longer a common ingredient in the American kitchen. Finally, I decided to use vanilla extract instead of rose water. Besides, in Simmons’s pound cake recipe, she doesn’t mention what kind of spice should be used. In my testing, I used allspice, which combines the flavor of cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves, as a substitution. Additionally, I chose all-purpose flour rather than cake flour, a finely milled flour with a low protein content, which is more commonly used in cakes in modern time.

Due to its large portion, I reduced the recipe by half. To begin with, I measured half pound of sugar, half pound of butter, five eggs, a teaspoon of vanilla extract, and a teaspoon of allspice. Although, it seems that you only need to mix everything together, I still have no idea of how to do it. Based on my previous baking experience, I first cut the butter into small cubes and mixed them well with sugar. When I got a relatively smooth mixture, I added eggs one by one until the paste was creamy. I have to admit that it is laborious work, even I reduced the recipe by half. That’s why I used my modern KitchenAid Stand Mixer, rather than mixing by hand. I put the vanilla extract in before adding the dry ingredients, a mixture of flour and allspice, into the paste. After the last step of blending, I got a bowl of thick and dense batter.

Before I put the batter into the oven, I wondered if I would get a perfect result. In Simmons’s recipe, she writes “watch it well, it will bake in a slow oven in 15 minutes.” First of all, she doesn’t mention which pan would be suitable. Moreover, I don’t know what the correct temperature is for a “slow oven.” Third, I’m pretty sure that the “15 minutes” baking time is absolutely impossible. Therefore, I transferred the batter into an aluminum foil loaf pan, a 2-pound standard size bread tin, and put it into a 350°F preheated oven. In the first 30 minutes, the cake barely puffed up and its color was pale white. After the next 30 minutes, the cake developed an even, nice golden color. To make sure the cake was done, I inserted a thin bamboo skewer into the center of the cake, and it came out clean. Then I checked the cake with a digital thermometer which showed the inner temperature was 200°F.

Fortunately, the result was far beyond my expectation. The cake not only looked appealing but was delicious to taste. The cake has a soft, buttery crumb that’s nearly perfect, and the cake was not too dense. While recreating this old pound cake, I was surprised by the generous usage of rose water in the recipe. Simmons’s pound cake calls for one gill of rose water, which equals to 24 teaspoons. Then, I’m so thankful for the modern kitchen equipment for helping me save my time and energy. I highly admire the housewives and the cooks, who used to work in the kitchen, and could only rely on heavy manual work and skilled technique in the past. The cake produced by this recipe notes the vague use of spices and plenty of rose water, but it still turned out well in the modern kitchen. The spicy taste and dense texture evoke a sense of an old, busy American kitchen. The recipe is centuries old, but the pleasure of eating is timeless.

Reference:

Simmons, Amelia. 1796. American Cookery. Hartford: Hudson & Goodwin.

Pound Cake. Date of Access. 14th Nov. 2019. http://www.poundcake.net/

Juliet Corson’s Boiled Rice-Dumplings

This guest post is part of a continuing series written by students from Karen Metheny's Cookbooks and History course. Ilana Hardesty details the challenge of making a historical recipe for boiled rice dumplings in a modern kitchen.

19th Century Cooking in a 21st Century Kitchen

Let’s be honest: there’s only so far I can go in simulating 19th century cookery. I have a 21st century kitchen (literally; it was gutted and renovated, painfully, in 2017). I live in a city, so I can’t build myself a wood-burning fireplace in which I can set things to the fire; I’ve got a Bosch dual-fuel range. I won’t be terribly successful with “pounding” my spices, as I don’t own a mortar and pestle, and can’t at the moment justify purchasing one for the purpose.

On the other hand, in terms of other responsibilities, I’m pretty well equipped. At the moment I’m nursing a husband with pneumonia, and fighting illness myself. I’m doing laundry (granted, in my modern washer and dryer), cleaning, trying to keep ahead of the falling leaves in the yard, and thinking about the 15 people due at my house for Thanksgiving in a couple of weeks. Perhaps I should be making items from the ‘caring for invalids’ chapters so often found in historical cookbooks. I could use a strong cup of beef tea right about now.

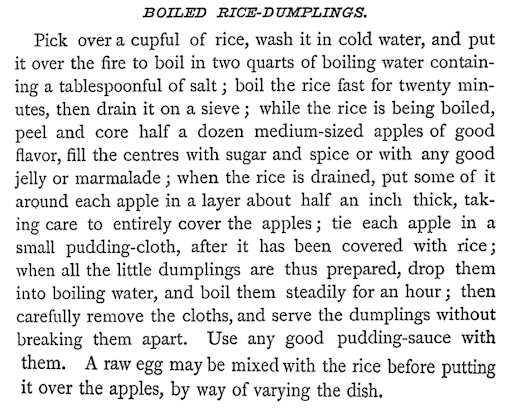

Instead, I’m trying Juliet Corson’s “Boiled Rice-Dumplings” (Corson 1885, 463-464). I wanted to make a boiled pudding, thinking that would be a better simulation than something in my electric oven. And these dumplings seemed a bit out of the ordinary. Essentially, they’re baked apples, except boiled, and with a rice “crust” rather than pastry (sort of an early, sweet, boiled arancini?). I wanted to stay away from a pastry because I’m terrible at making pastry even in 2019. I would surely fail an 1885 puff “paste!”

The recipe calls for six apples to be cored and peeled, and flavored by adding “sugar and spices” or “any good jelly or marmalade” into the tunnel left by the core. The apples are then wrapped in a layer of cooked rice, tied up in a “pudding-cloth,” and boiled for an hour.

Trial 1 (Monday)

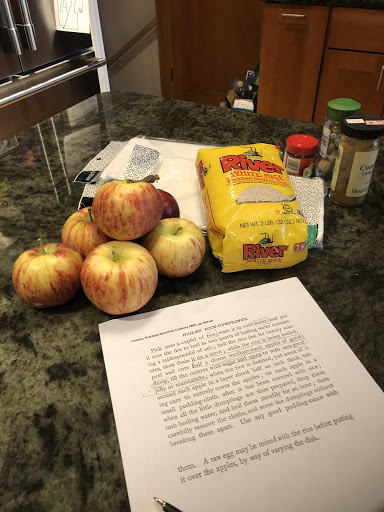

I assembled my ingredients, all purchased at the Watertown Stop & Shop. I did not need to pick over or wash my River® Rice, of course. Without a grain length specified, I went with medium grain rather than long grain (figuring medium grain would stick together better). The apples are locally grown. They are Cortlands – the smallest I could find; do they give apples growth hormones these days? – as a substitute for Pippins. I used cheesecloth as an approximation of “pudding-cloth.” I suspect I’d have been better off sourcing muslin or sacrificing one of my kitchen towels to the cause. In this round, I went with the “sugar and spices” option, and mixed up a bowl of white granulated sugar with pre-ground nutmeg and cloves (none of the recipes I looked at for any puddings called for cinnamon, but many called for nutmeg and cloves).

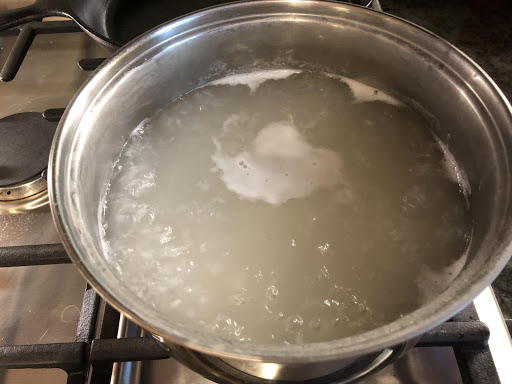

I set the rice to “boil fast for twenty minutes,” then drained it “on a sieve” (well, through a sieve, actually).

As that was happening I peeled and cored the apples. Did I take refuge in my OXO peeler and corer? Yes I did!!

Then came the tricky part, where I was instructed to cover each apple with a half-inch thick layer of the cooked rice, somehow AFTER I’d filled the core with sugar! Now I think of it, perhaps I was meant to have left the bottom of the apple intact. Instead, I devised an assembly that appeared would work, until it didn’t. I spread a layer of rice on my cheesecloth, wide enough in diameter, I figured, to be pulled up around the apple when I cinched the cloth. Then I put the apple in the center of the rice, spooned in the sugar mixture, topped with more rice, and pulled together the corners of the cloth, to tie them tight around the rice-covered apple.

Unfortunately, I ended up with only enough rice to make four, not six, apples. Did I use too much rice on each apple? It didn’t seem that way. Are today’s “small” apples even too big for the recipe (which actually calls for medium apples)?

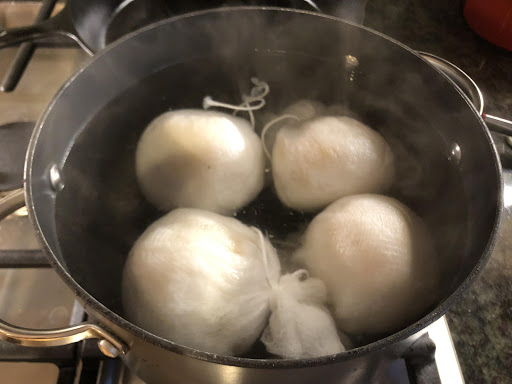

Here they are, just after being put into the pot of boiling water. They float!

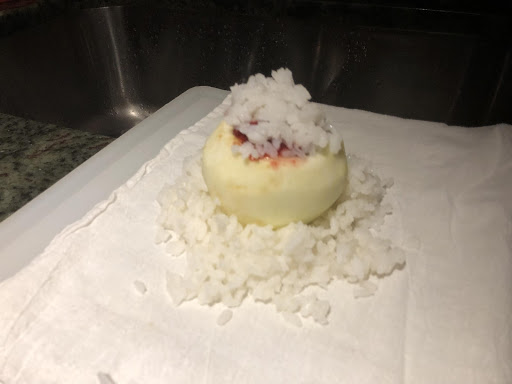

There was no indication of what to do when they came out of the boiling water, so I set them on a rack to drain for a few minutes, and then gingerly opened one packet.

There was no indication of what to do when they came out of the boiling water, so I set them on a rack to drain for a few minutes, and then gingerly opened one packet.

Amazingly, they held together!

And the verdict? They’re odd. Not inedible, but not delicious. Perhaps I was expecting/wanting something much more sweet and dessert-like. The rice got more gluey, and so held together. And, while I haven’t investigated the science, I suspect the pectin in the apple helped it keep its shape during cooking as well, as happens with a regular baked apple. The texture is almost doughy, and the apple sort of melds with the rice.

Next time, I may try (and I know I’m changing too many variables):

- Corson suggests adding an egg to the rice as a variant. This would also, I think, help the rice adhere to the apple and hold together. I might consider this.

- She also says to “use any good pudding-sauce with them.” She has a variety of sauces in her Puddings chapter, any one of which would make the dumplings taste better. I will plan on making a sauce.

- Try to spread the rice a bit thinner

- Use something a bit less open-weave than the cheesecloth I have

- Try a jelly or marmalade instead of the sugar and spices

Trial 2 (Wednesday)

The cooking gods are evidently after verisimilitude. This morning, the coldest day since last winter, the furnace blew. So, no heat and a pneumonia-sufferer to keep warm. And also cooking to do.

This round was easier, since I’d done it once, but no less fiddly. Who had the time to surround these apples in rice and wrap them in muslin?? I made the recipe as written, and did not add the suggested egg. I used smaller apples, so managed to get five made this time around. Still not the six the recipe says I’ll get, but closer. Also, after perusing modern recipes for baked apples, I did not use the apple corer this time. Instead, I used a paring knife to cut around the stem end, then used a small spoon to scrape out the core and seeds, while leaving the bottom of the apple intact.

I cut up a cotton kitchen towel to use instead of cheesecloth, and that was easier to manipulate. I developed a process where I just mounded rice around the apple, and manipulated it into place as I pulled up the cloth around the apple. This time I tried a jelly – a homemade cranberry-apple sauce made with the leftover apples from Monday, sweetened with a bit of sugar and flavored with spiced boiled cider. I will not manage a pudding-sauce, though I know a good sauce makes anything taste better.

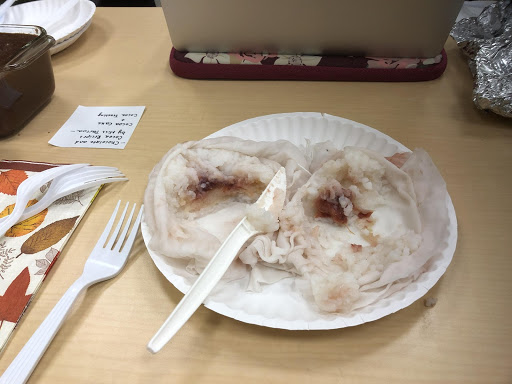

These were not, somehow, as aesthetically pleasing (perhaps the color of the cranberry sauce was to, um, visceral?). Also, the apples disintegrated a bit more this time. Though they apples were picked from the same bin, perhaps some other varieties ended up in the mix, and these did not hold their shape as well.

The verdict this time, from the class, was positive! We all agreed that this is not necessarily a dessert, but might be a nice sweet accompaniment to, for example, a roast pork dish, with a fruit-based sauce. There is work to be done in getting them out of their pudding-cloths intact, but it may be that the problems I had with that were because they had been cooled and then reheated. Perhaps the rice had a chance to fuse to the cloth more than if I’d served them straight from the boiling pot.

Overall, this was a fascinating experience. I was hyper-aware of the conveniences that I have that Juliet Corson and her readers did not. But I was also hyper-aware of the cooking knowledge I have, and of my ability to infer and adapt with very little recipe detail. I look forward to taking on this challenge again with other recipes, for myself!

Works Cited

Corson, Juliet. 1885. Practical American Cookery and Household Management. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

Cocoa Cake from Chocolate and Cocoa Recipes by Miss Parloa and Home Made Candy Recipes by Mrs. Janet McKenzie Hill

This guest post is part of a continuing series written by students from Karen Metheny's Cookbooks and History course. Mara Sassoon shares her experience with recreating a historical recipe for cocoa cake.

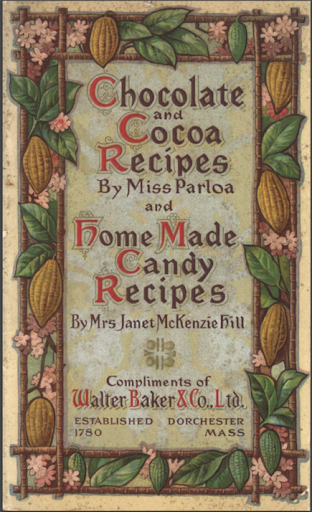

When it came to deciding on a historical recipe I wanted to recreate, I knew I wanted to make something chocolatey. What better source for such a recipe than the 1909 cookbook Chocolate and Cocoa Recipes by Miss Parloa and Home Made Candy Recipes by Mrs. Janet McKenzie Hill? The book features recipes from Maria Parloa and Janet McKenzie Hill that utilize Walter Baker & Co. chocolate products.

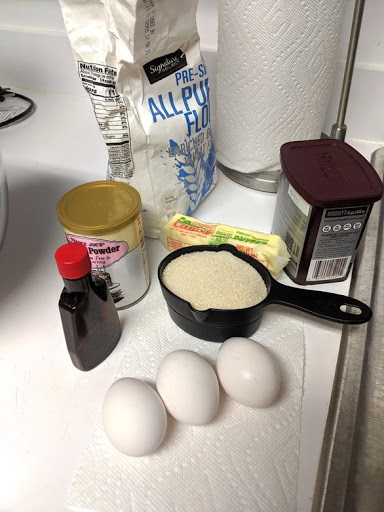

I decided I wanted to make a cake and settled on Parloa’s recipe for Cocoa Cake (1909, 25) because I already had the ingredients the recipe calls for on hand.

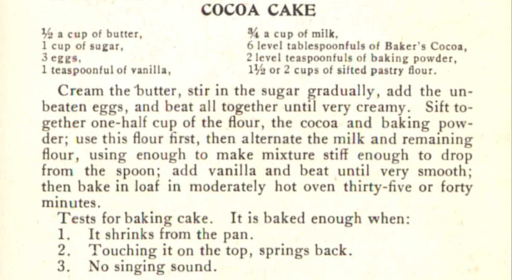

Here is the recipe:

Though Baker’s brand chocolate still exists (the company is today owned by Mondelez International), Baker’s brand cocoa is no longer produced. I wound up using Hershey’s brand cocoa. I also didn’t have pastry or cake flour on hand, so I used all-purpose flour. The recipe was fairly straight forward. I started with very soft, unsalted Cabot butter, creamed it, mixed in the cup of sugar, then added all three eggs at once and beat those in. Typically, the more modern chocolate cake recipes I’ve made call for less eggs and often specify adding the eggs one at a time.

The recipe got a little bit vaguer from there: “Sift together one-half cup of the flour, the cocoa and baking powder; use this flour first, then alternate the milk and remaining flour, using enough to make the mixture stiff enough to drop from the spoon.” All in all, the recipe calls for 1 ½ to 2 cups of sifted flour. I wound up using 1 ½ cups. I whisked together the half cup of flour, cocoa powder, and baking powder in a separate bowl, then sifted that into the butter/sugar/egg mixture. I decided to interpret “alternate the milk and remaining flour” as pour some milk, mix, sift in some flour, mix, add more milk, mix, add more flour, etc. As mentioned, 1 ½ cups of flour seemed like enough—the batter was very thick.

After mixing in vanilla extract, I scraped the batter into a glass loaf pan that I had greased even though the recipe did not say to grease the pan. I think the cake would have stuck to the baking dish had I not done so. The recipe called for baking the cake in a “moderately hot” oven, which I interpreted to mean 350 degrees, for 35 to 40 minutes. I was excited that I found a historic recipe that specified baking time, however, when I pulled the cake out of the oven at the 35-minute mark, it was slightly soupy in the very middle. I baked the cake for another 10 minutes, but when I stuck a toothpick in the center to test its doneness, there was still a lot of batter on it. I put the cake back in the oven for another 15 minutes, conducted the toothpick test again, and concluded it was baked through.

Parloa actually included three tips for determining if a cake is done with this recipe: “1. It shrinks from the pan; 2. Touching it on top, springs back; 3. No singing sound.” After baking the cake those last 15 minutes, I determined the cake fit the criteria for tips #1 and #2. As for step #3, my cake never sang to me throughout the baking process, but that would have been a welcome surprise!

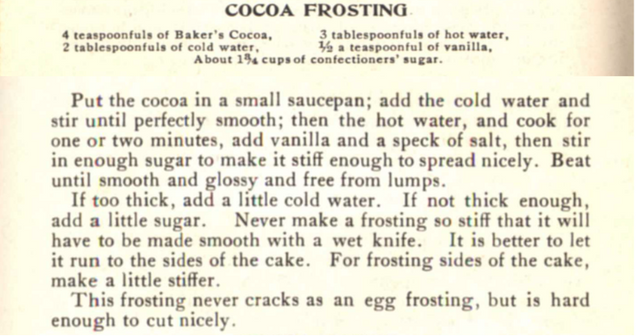

After baking the cake, I thought, “Why stop there?” I decided I’d make Parloa’s recipe for Cocoa Frosting (1909, 24) to top the Cocoa Cake.

Again, I used Hershey’s cocoa powder instead of Baker’s. This is a very simple frosting recipe, calling for only cocoa, hot and cold water, vanilla, confectioners’ sugar, and salt. I mixed the cocoa and cold water in a saucepan, then added the hot water. The recipe got confusing when it said “cook for one to two minutes.” I decided I’d cook the mixture on medium heat, adding in the vanilla, salt, and sugar as it was cooking.

This was an extremely thin mixture, so I turned the stove temperature down to low and heeded the recipe’s advice: “If not thick enough, add a little sugar.” I wound up having to add more than “a little” more sugar—about another cupful—until I thought it seemed somewhat thicker. I poured the frosting into a glass Pyrex container and refrigerated it overnight; the refrigeration helped it get a little thicker, too.

I poured it on the cake next day, the same day I was to bring the cake into class. After sitting at room temperature all day, the frosting thinned again by the time it came to present the cake in class. But, since it seeped in throughout the day, I think it actually added a little necessary moisture to the cake, which was a little drier and denser than I was expecting (possibly from using all-purpose flour). Perhaps if I had followed Parloa’s recipe to a T, it might have been a bit lighter and fluffier. Nonetheless, the cake turned out quite tasty.

Works Cited: Hill, Janet McKenzie, and Maria Parloa. 1909. Chocolate and Cocoa Recipes by Miss Parloa and Home Made Candy Recipes by Mrs. Janet McKenzie Hill. Dorchester: Walter Baker & Co., Ltd.

A Taste of the Past: Real Shrewsbury Cakes

Students from Karen Metheny's Cookbooks and History course are contributing guest blog posts about their assignment to recreate a historical recipe. The first of this series comes from Kaya Williams.

A Taste of the Past: Real Shrewsbury Cakes

Consider this a recipe for adaptability: Take one 19th-century recipe and combine with 21st-century technology. Sprinkle in a nearly-forgotten deadline and a pinch of last-minute grocery shopping (be careful not to overseason with hustle). Place in a tiny and sparsely-stocked kitchen for one to two hours and bake until cooked through.

It was a baking experience unlike any other I had encountered: a centuries-old recipe modified for the present day, with challenges and delights alike spilling out of the bowl. In the process of baking “Real Shrewsbury Cakes” from Priscilla Homespun’s The Universal Receipt Book (1818), I became hyper-aware of the ways in which my modern kitchen could compromise the integrity of the historical recipe.

As soon as I began preparing the cookies, I realized just how historically inaccurate my kitchen could be, with anachronisms baked into this five-ingredient recipe.

I deliberately selected a recipe whose ingredients would not be impossible to find, avoiding entries that featured rosewater, pearlash, or lively emptings. But as I ticked off the items on my shopping list, I began to realize that even though the ingredients were the same in name, they may not have been manufactured by the same process. The all-purpose flour I used was likely machine-ground, giving it a finer texture than flour produced in an older mill.

Likewise, the butter I used was mass-produced and kept rather firm in refrigerated transport, making it more difficult to combine with dry ingredients than would have been the case with home-churned or locally-made butter. The “powdered loaf sugar” that I used — sold in plastic packaging at Whole Foods — is also a far cry from that which may have been available at the time the recipe was created; I imagine that my store-bought, pre-ground cinnamon from Trader Joe’s is not what the cookbook’s author had in mind when she called for “a dram of beaten cinnamon.” Without close proximity to a chicken farm, the eggs I used weren’t nearly as fresh as they may have been for a home cook in the 19th century who may have owned their own chickens.

Though my ingredients were lacking in historical veracity, the confines of my modern kitchen may have been the greatest influence on the recipe’s temporal accuracy. Nearly every tool I use for preparation was made of plastic or silicone — materials not invented nor used commercially until nearly a century later (Science History Institute, n.d.; SIMTEC 2016). My stove and oven are fueled by electricity, not gas or a wood-burning flame. And it was near-impossible not to glance at the digital clock on my microwave to keep track of time — a privilege in which no 19th-century cook could indulge. But my greatest historical inaccuracy was also the one thing preventing my recipe from disaster: lacking a kitchen scale, I used Google to find conversions from weight to cup and tablespoon measurements. It’s a tool no 19th-century (and very few 20th-century) chefs could use to ensure that their recipes would succeed, but if I was going to present the finished product to others, I knew I couldn’t eyeball the measurements and still produce something edible.

Nevertheless, some techniques were maintained if for nothing else than a lack of equipment, like hand-mixing dough (I do not own an electric mixer). Instructions to cut the dough using a wine glass were easy enough to follow, and though I didn’t have a rolling pin, a drinking glass sufficed to flatten the dough. Likewise, the parchment paper I purchased was unbleached and sold in cardboard packaging — not too far off from the quality and consistency of paper available in the 1800s.

I also incorporated some of my own baking knowledge to ensure baking success; rather than combining all ingredients at once, I first cut the butter into the flour as I would a pie crust to avoid a sloppy, sloshy mess, and I knew that a 350-degree oven would be standard enough that it would bake the cakes through without burning them. (Whether or not it was actually a “quick” oven, I wasn’t entirely sure.) When instructions called for the dough to be rolled “out thin enough for an ounce weight of the paste to make a cake as large as the top of a breakfast cup or basin” or rolled out somewhat thicker to be as large as the top of a wine glass (Homespun 1818: 20), I reverse-engineered the measurement by first balling an ounce of dough and flattening it to fit the space, then using that as a point of reference for rolling out the rest of the dough.

The greatest challenge wasn’t time or equipment but physical space: though the recipe’s ingredients weren’t outrageously proportioned, my kitchen is so small that I could not roll out all the dough at once. (Even rolling out half the dough at one time at the designated thickness began to spill over the edge of the counter). I also had to bake the dough in batches of eight on half-size baking sheet, as my oven is too small to fit a full-size sheet.

Even so, the final product — two dozen pale, shortcake-like cookies — was a success by most metrics. Though I personally prefer a moister cookie (and thus found these “Real Shrewsbury Cakes” rather dry), several tasters with an affinity for shortcake found them tasty. It’s unlikely that I’ll return to this recipe again, but the relative ease of producing the recipe made me eager to explore the possibilities that await in the world of historical cookbooks. Perhaps the best treats aren’t the newest but the ones proven tried and true by time itself.

Bibliography

Homespun, Priscilla. 1818. The Universal Receipt Book. Philadelphia: Isaac Riley.

Science History Institute. n.d. “The History and Future of Plastics.” Accessed November 18,

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/the-history-and-future-of-plastics.

SIMTEC. 2016. “The History of the Silicone Elastomer.”Accessed November 18, 2018.

https://www.simtec-silicone.com/the-history-of-the-silicone-elastomer/.

Spring 2020 Course Highlight: ML720 U.S. Food Policy and Cultural Politics

This post was written by current student Sarah Critchley.

The time has come to start thinking about spring courses! While it's tough to choose with so many excellent options, may I present a case for taking ML720 U.S. Food Policy and Cultural Politics?

When I took U.S. Food Policy with Dr. Ellen Messer in the Spring semester of 2018, current politics provided a relevant framing for the class. The new Farm Bill, expected to come out every five years, was crawling through our systems of government as our class moved towards the end of the semester; learning about the issues in the bill that the Congress and Senate were debating in real time added weight to the urgency of learning about the way our food system is structured in the United States and how it got to be the complicated structure that it is today. As a person who tries her best to be politically active and aware, learning more about SNAP, WIC, and other programs covered in the Farm Bill at the moment they were in the news for having their funds cut improved my ability to be an informed citizen.

The course covers the gamut of food systems, food chains, and how governmental and non-governmental institutions control the way food is grown and dispersed. Dr. Messer has had a long and esteemed career studying food from an anthropological perspective, and she shared her extensive knowledge as well as the connections she has made over the years with guest lecturers. Representatives from Indigo Ag came to speak to us about the ways that tech companies are trying to create solutions for climate change-driven problems in farming, and Tristan Noyes from the Maine Grain Alliance came to speak to us about organic farming and revitalizing local grain economies in the Northeast. The assignments were diverse in their approach to learning; our projects included studying one commodity from every stop on its way to the consumer (I am an eggspert on eggs now, ask me anything), discussion of documentaries like King Corn, and researching local food policies in the state or region of our choice.

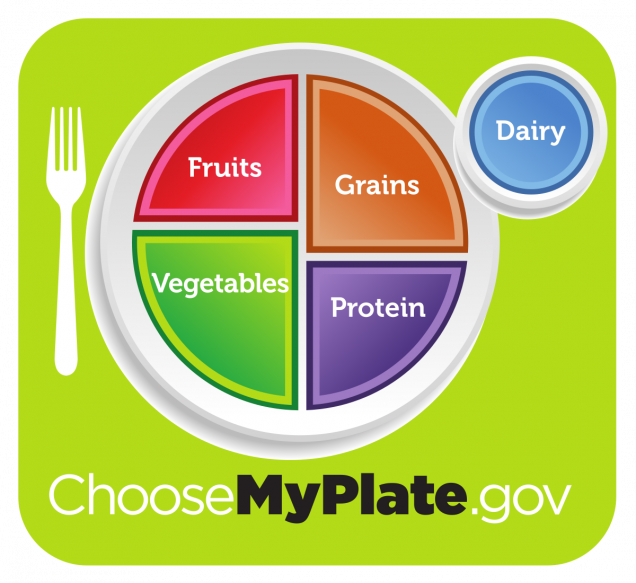

I don’t know if I will go into food policy after I graduate the program, but I deeply appreciate the knowledge that this course gave me and how relevant it is to the rest of my coursework in the Gastronomy program. When we studied Julie Guthman’s Weighing In, I made connections to the kinds of arguments that nutrition-focused policy venerates as the way forward to healthy Americans. In reading Alkon and Agyeman’s Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability, I was able to engage with ideas of social justice within sustainable food practices through different angles after learning about the policies in place to control large and small-scale farmers. When we read Hayes-Conroy’s piece "Feeling Slow Food: Visceral Fieldwork and Empathetic Research Relations in the Alternative Food Movement" investigating research methods in the Slow Food movement for the Food and the Senses course, I felt I had a good understanding of the mission and the people she was examining. In the Sociology of Taste course I am taking this semester, it’s been helpful to understand U.S. food policy in studying how our tastes are created, and how governmental policies play into what farmers grow and what foods become more valued than others. Specifically taking a class on U.S. food policy instead of trying to merely absorb it as I navigate the Gastronomy program gave me a foundation of knowledge to use in the rest of my courses as I seek to critique, question, and understand the history and the status quo of food in our society.

The Food Podcast Colloquium

Please join us for this special event!

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

6 pm to 8 pm

Center for Integrated Life Sciences and Engineering (CILSE), room 106B

610 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston MA

Panelist include

- Cynthia Graber - Gastropod

- Sara Joyner and Kaitlin Keleher - Proof, from America's Test Kitchen

- John Rudolph - Feet in 2 Worlds

Moderated by Kathy Gunst, Resident Chef for NPR’s Here and Now and author of the upcoming book Rage Baking—The Transformative Power of Flour, Fury and Women’s Voices.

Please register for a free ticket at our Eventbrite site.

Refreshments will be served.

This event is organized by the Boston University Gastronomy Program, and supported by a grant from the Association for the Study of Food in Society (ASFS).

Ice Cream, History, and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: A Halloween Post

This post was written by current student Hannah Spiegelman. Read more of her work here.

Happy Halloween season, fellow gastronauts! Many assume that Halloween’s food connections start at candy and end at pumpkins, but I like to dispel that belief. This season, I created a handful of spooky-themed ice cream flavors inspired by history and literature. If you aren’t familiar with my work, I have an ice cream concept called A Sweet History (@asweethistory) where I create ice cream/sorbets/and other frozen-focused desserts whose backstories reside in history, art, etc. I also do local small commissions from time to time (if you are interested email me at asweethistory@gmail.com)! Enjoy my favorite from my Halloween series below and let me know what frightening flavors I should make next year!

Mary’s Monster: Swiss Chocolate Charcoal Poppyseed Ice Cream with Cherry Curd topped with Candied Fennel Stalk

The year is 1618, also known as the year without a summer. The year prior, Mount Tambora (in modern-day Indonesia) erupted, setting off climate abnormalities throughout the northern hemisphere. In Switzerland, it was a rainy and cold summer. Low temperatures caused a dam to freeze. But this didn’t stop Mary Wollstonecraft Goodwin, her soon-to-be husband Percy Shelley, and her step-sister Claire Clairmount from joining Lord Byron, the renowned poet, at a rented villa on lake Geneva.

Mary, daughter of feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, had met the already married poet Percy when she was 16 years old. He and his wife were estranged, so he spent much of his time with the young aspiring writer. Mary fell deeply in love and by the time they summered in Switzerland, she had supposedly lost her virginity in a graveyard; had a premature baby, who died; watched Percy have an affair with Claire; and struggled financially since her father did not approve of Percy despite his beliefs of free love.

The trio arrived in Switzerland in May 1816, but soon realized they had to spend the majority of their time inside due to the weather. A possible liquid opium-driven orgy led the group, which now included Lord Byron’s personal physician, to recite German ghost stories. Then, one night, Byron had the idea for everyone to create their own ghost story to share. Mary did not want to disappoint her companions and she passed for many nights following. After an evening discussion of galvanism, she dreamt of what would become her most famous work. And what was meant to be a short story turned into the novel, “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus.”

The inspiration for the name Frankenstein most likely came from the Frankenstein castle in Darmstadt, Germany, where centuries before an alchemist claimed to create an “elixir of life.” Frankenstein literally translates to stone of the Franks, a Germanic group. Mary’s subtitle alludes to one of the book’s main themes: bringing something new into the world only to be afraid of it. In mythology Prometheus brought fire to humans hidden in a fennel stalk. In Mary’s novel, Dr. Frankenstein reanimates pieced-together body parts into a human form, but doesn’t know how to control his own creation.

Since 19th century society worried about controlling women, Mary’s name wasn’t on the first edition of “Frankenstein,” published when Mary was only 18 years old. Five years later, the second edition, published in two parts, gave her full credit. And on Halloween of 1831, a “popular” edition was published, in which Mary revised to be less controversial. This edition is what we all read today, veiling the political and social discourse Mary embedded into her works. Without her consent, her work began to be adapted by theaters, and pop-culture today proves the story has been blown-out and distorted.

Despite the deaths of many close to her including Percy the years following the publication of “Frankenstein,” Mary continued to write novels, essays, biographies, book reviews, and articles. While Mary worked to publish her late husband’s works, elevating him within the literary cannon, her own career was seen as a hobby, causing her to struggle financially. Since her acclaimed first novel was originally published anonymously and began with a forward by Percy, critics believed that he was the writer for surely an eighteen year old could not write such prose. To these readers’ chagrin, a late night dream on a frigid summer night sparked one of the greatest gothic novels written by the foremother of science fiction.

Summer at Rare Book School

Written by current Gastronomy student Laura Kitchings.

As an Archivist who is a current Master’s Candidate in the Gastronomy program, I am always trying to find ways to incorporate my professional training into my study of food. This summer I was fortunate to attend the 30-hour, 5-day workshop “The History of the Book in America: A Survey from Colonial to Modern” at Rare Book School (RBS) at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. Rare Book School is an organization that provides educational opportunities to study the history, care, and use of written, printed, and digital materials. The course was co-taught by Scott E. Casper and Jeffrey D. Groves who have published extensively on the History of the Book in America both separately and as a team. Our twelve-person class included antiquarian booksellers, librarians, archivists, and graduate students. I attended the class as part of my thesis research, focusing on cookbooks in the 1890’s. My goal in attending the program was to place the cookbooks of the 1890’s in the larger book history of the United States. While I had studies Special Collection Library management as part of my Master’s in Library Science at Simmons College (now Simmons University) I had never taken a course in the History of the Book.

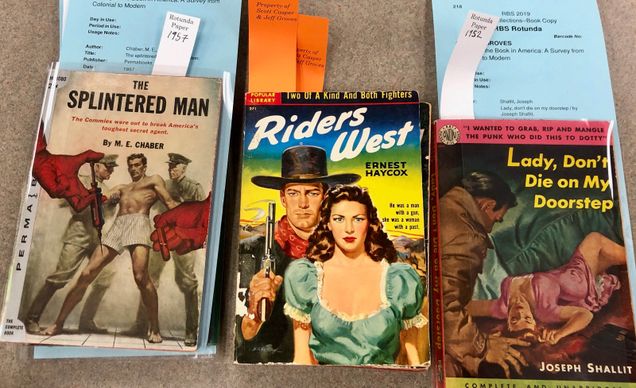

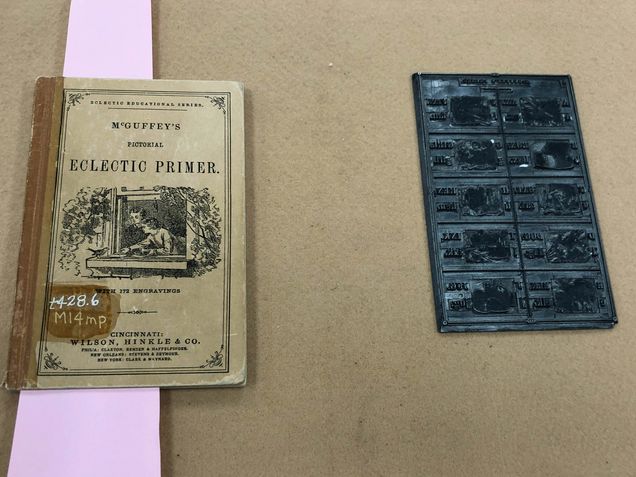

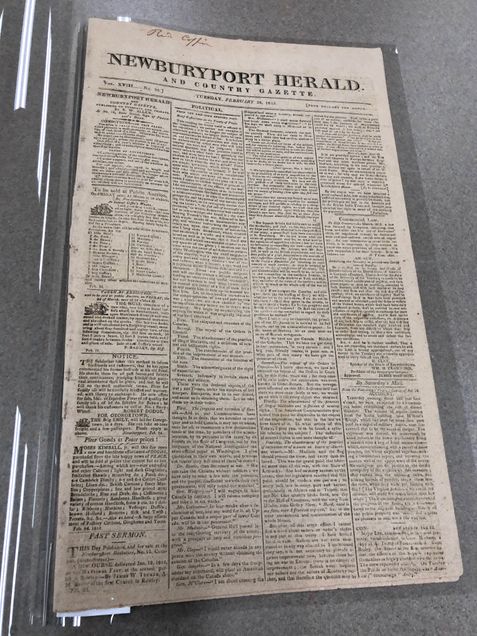

Each of the five days during the workshop was divided into four sessions. I expected each session to consist of a lecture around an aspect of book history. Instead, each day was a mix of lecture, and activities. The various activities, including as comparing educational texts, almanacs, newspapers, and paperback books from a variety of time periods. As you can see from the examples below, each activity involved working with materials held by RBS and active discussion with classmates.

These activities allowed me to consider possible comparison cookbook activities in a library setting.

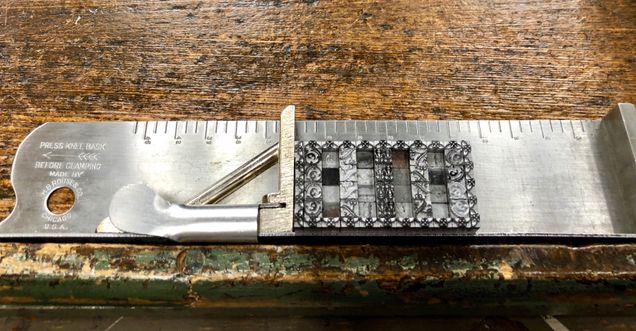

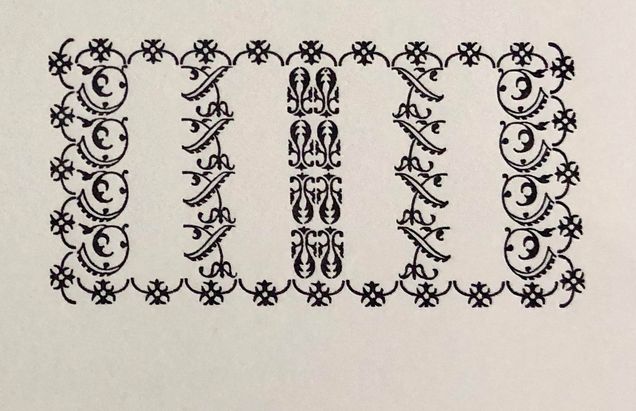

While our class was focused on Book History, we were also able to see what other courses were studying. One evening we were able to work with the Vandercook proof press that included the need to hand set type.

While our team struggled with placing the small metal pieces of type to prepare to actually print on the press, I found myself reflecting on how printing, like cooking, involves significant preparation and muscle memory. While I was frustrated in the movement while placing the type, I found myself thinking about the Saturdays I spent learning knife skills in MET ML 698 –Laboratory in the Culinary Arts: Cooking.

As with learning knife skills, I realized that if I had to regularly work with the small type, it would become Embodied knowledge.

On the last day, each member of the class presented on the future of the book. While my classmates focused on performative reading on social media and linked data, I focused on cookbooks. I was able to use work done as part of a team in MET ML 671- Food and Visual Culture. My presentation focused on how cookbooks now need to include significant visual elements such as photographs and illustrations, and how successful cookbook authors need to have a social media presence.

While it was an exhausting week, I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to attend the workshop and hope to find opportunities to teach with historic cookbooks in the future.