Welcome New Gastronomy and Food Studies Students for Fall 2020

We look forward to welcoming a wonderful new group of students in our fall 2021 classes, and hope you will enjoy getting to know a few of them here.

In the 1970s, people didn’t eat cardamom ice cream, at least not in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Gretchen Kurtz grew up. But one night, staying up past bedtime to ring in the New Year with her parents, Gretchen tried it, and realized there was a world of flavor she’d never heard of. Since then, she’s spent her life learning about foods, cooking techniques and recipes, and is especially drawn to what they say about the people and culture that produced them.

In the 1970s, people didn’t eat cardamom ice cream, at least not in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Gretchen Kurtz grew up. But one night, staying up past bedtime to ring in the New Year with her parents, Gretchen tried it, and realized there was a world of flavor she’d never heard of. Since then, she’s spent her life learning about foods, cooking techniques and recipes, and is especially drawn to what they say about the people and culture that produced them.

After graduating Princeton with a degree in comparative literature, Gretchen worked for several years in Paris, London and New York, where she spent weekends mapping out and visiting the cities’ best bakeries, tea salons and bistros. If the internet had been a thing back then, she would’ve surely started a blog about her experiences. Later she transitioned to food writing, first as an editor/writer at magazines and newspapers in New York City and Denver, including the New York Times and the Denver Post, and ultimately eating her way to a job as restaurant critic for Westword, an alt-weekly in Denver. After seven years in the role, Gretchen decided it was time to have different conversations about food than “what’s the best restaurant?” and happily discovered BU’s gastronomy program.

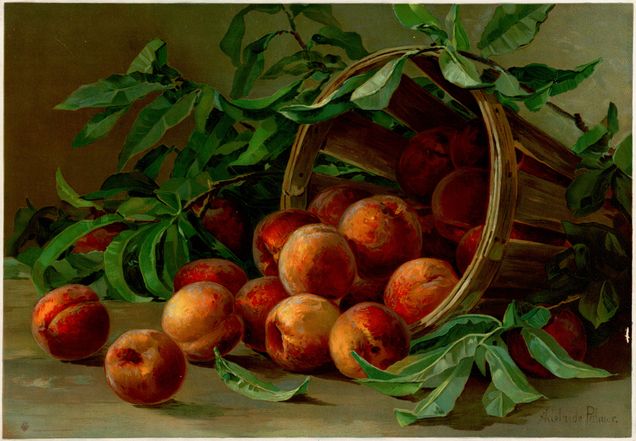

Though restaurants have been her niche, Gretchen never lost the thrill of home cooking, and loves nothing more than going to a farmers market, picking out peaches, tomatoes, squash and basil, and heading straight into the kitchen. To her, one silver lining of this pandemic has been the time to teach her three normally-busy teenagers how to braise, macerate, and make stock.

Julian Plovnick is a local guy hailing all the way from the distant streets of Brookline, MA. His obsession with food began when he was gifted his first knife set for his bar mitzvah (which he still uses to this day) along with a copy of Good Housekeeping's Children's Cookbook. Having noticed that he spent more time in the kitchen than on the dance floor, the caterer of the party offered Julian the opportunity to help her out with future events as a server and kitchen assistant. Thus, Julian's culinary journey began.

Julian Plovnick is a local guy hailing all the way from the distant streets of Brookline, MA. His obsession with food began when he was gifted his first knife set for his bar mitzvah (which he still uses to this day) along with a copy of Good Housekeeping's Children's Cookbook. Having noticed that he spent more time in the kitchen than on the dance floor, the caterer of the party offered Julian the opportunity to help her out with future events as a server and kitchen assistant. Thus, Julian's culinary journey began.

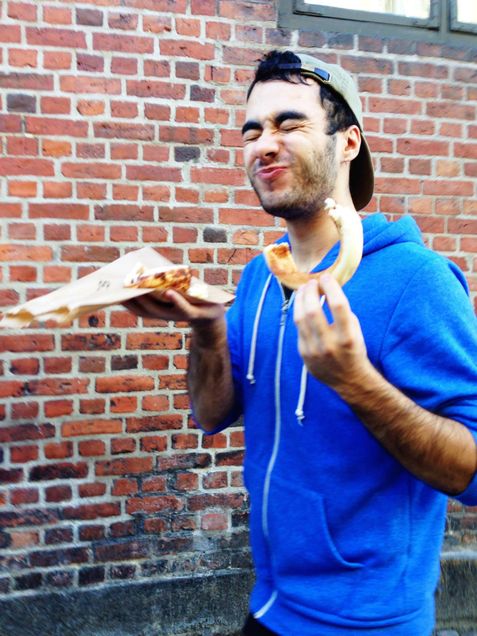

Fast-forward a couple years, and Julian received his English degree at Vassar College in New York's Hudson Valley (conveniently located 20 minutes away from the Culinary Institute of America). After graduating, he combined his love of food with his editorial talents at a variety of food-focused companies such as Clover Food Labs, culture: the word on cheese, and ezCater, where he's spent the last 4 years. Julian's ecstatic to continue along on his culinary journey within BU's Gastronomy Program, where he plans on furthering his skillset in food writing, recipe development, and business operations.

Marie-Louise Friedland was born and raised in her family’s French restaurant in San Antonio, Texas and from her time there as a child, she has had a passion for the Food & Beverage industry. She started with waiting tables in high school and branched out to try everything from being a cheesemonger to working in catering to becoming a Certified Sommelier as a way to fuel her passion.

Marie-Louise Friedland was born and raised in her family’s French restaurant in San Antonio, Texas and from her time there as a child, she has had a passion for the Food & Beverage industry. She started with waiting tables in high school and branched out to try everything from being a cheesemonger to working in catering to becoming a Certified Sommelier as a way to fuel her passion.

It was while working as a captain and Sommelier in Austin that she knew she wanted to travel as much as possible to learn about wine so she packed up everything and headed to San Francisco. It was there that she worked as a Manager and Wine Director, pushing her to immensely grow her palate. These positions allowed her to travel to famous wine regions but also allowed her to develop management and team building skills.

Following the desire to keep growing within the industry she moved back to Texas and explored more of the management side of restaurants. It was seeing the industry from this vantage point that pushed Marie-Louise to apply to a program that can equip her with the necessary education to help progress the industry forward. She is excited to join Boston University’s Master’s in Gastronomy program because she knows graduate school will give her the well-rounded understanding of all issues pertaining to the Food & Beverage world outside of restaurants. When she isn’t studying she is probably playing with her cat Billy, cooking something with her husband, record shopping or reading some Stephen King.

Haley Ornitz was born and raised in the Northeast surrounded by many creative family members, who inspired her to develop a passion for the arts and working with her hands at a young age. She studied Art/Art History at Bucknell University and has worked at non-profit and for-profit arts organizations in New York City and Boston for the past 10 years. Throughout her life, Haley has channeled her energy into many tactile crafts, including painting, calligraphy, pottery, knitting, and cooking, her favorite form of creative expression. She is excited to build upon her passion for food by pursuing her MLA in Gastronomy, a topic she became interested in for many of the same reasons she was drawn to Art History as an undergraduate. Similarly to studying society through a painting or an art movement, she loves learning about culture, history and political economies through the lens of a particular dish, type of regional cuisine or aspect of the food system. In addition to her studies, she is looking forward to exploring how she can apply her experience in the arts to a creative and meaningful career in the food industry. In her free time, Haley loves cooking and eating with family and friends, reading cookbooks cover to cover, and spending time outside with her husband and dog, Ranger.

Haley Ornitz was born and raised in the Northeast surrounded by many creative family members, who inspired her to develop a passion for the arts and working with her hands at a young age. She studied Art/Art History at Bucknell University and has worked at non-profit and for-profit arts organizations in New York City and Boston for the past 10 years. Throughout her life, Haley has channeled her energy into many tactile crafts, including painting, calligraphy, pottery, knitting, and cooking, her favorite form of creative expression. She is excited to build upon her passion for food by pursuing her MLA in Gastronomy, a topic she became interested in for many of the same reasons she was drawn to Art History as an undergraduate. Similarly to studying society through a painting or an art movement, she loves learning about culture, history and political economies through the lens of a particular dish, type of regional cuisine or aspect of the food system. In addition to her studies, she is looking forward to exploring how she can apply her experience in the arts to a creative and meaningful career in the food industry. In her free time, Haley loves cooking and eating with family and friends, reading cookbooks cover to cover, and spending time outside with her husband and dog, Ranger.

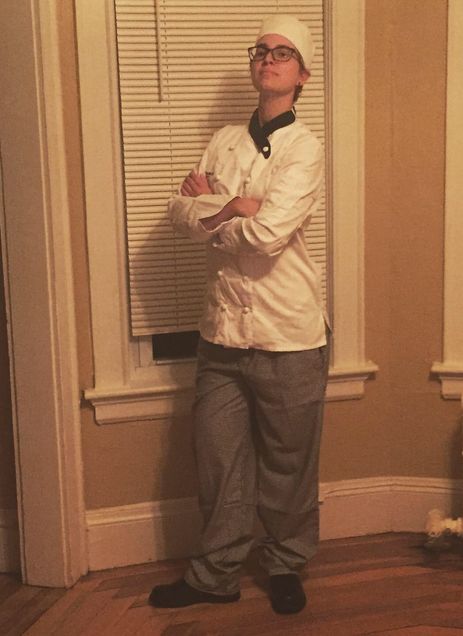

Bella Brookes first developed an interest in food preparation at the age of two, when she learned that messes were okay if it was because you were covering a cake in chocolate frosting and sprinkles. Originally from central Florida, she spent her formative years in Boulder, Colorado. Her formal interest in food was piqued when she spent four years getting a bachelor's in Cognitive Science in L.A. and was fully immersed in an international food culture. So much was the interest in food that she decided to completely turn her life around and spent one year at Johnson & Wales University's Pastry program in Rhode Island.

Bella Brookes first developed an interest in food preparation at the age of two, when she learned that messes were okay if it was because you were covering a cake in chocolate frosting and sprinkles. Originally from central Florida, she spent her formative years in Boulder, Colorado. Her formal interest in food was piqued when she spent four years getting a bachelor's in Cognitive Science in L.A. and was fully immersed in an international food culture. So much was the interest in food that she decided to completely turn her life around and spent one year at Johnson & Wales University's Pastry program in Rhode Island.

Bella took several jobs in bakeries in different locations before deciding to pursue the academic aspects of food and culture. She thinks her professional training will provide a practical background for studying the interactions between food and culture. Her current goal is to work in a publishing environment that focuses on food history and the evolution of food from straightforward sustenance into the nuanced and prominently social culture it is today.

Jen Wood is from Worcester, Massachusetts where she has been a licensed massage therapist and small business owner for over 16 years. She received her B.A. in Anthropology, with a concentration in Environmental Sustainability, May 2020 from Southern New Hampshire University. Her passion for food history and culture came out of her early college years as an anthropology student at New Mexico State University in the early 1990s, after reading anthropologist Marvin Harris’s work on cultural food customs and taboos. While cooking and baking have been an interest since childhood, the plan to study food and anthropology became clear thanks, in part, to nutritional anthropologist Deborah Duchon and chef Anthony Bourdain.

Jen Wood is from Worcester, Massachusetts where she has been a licensed massage therapist and small business owner for over 16 years. She received her B.A. in Anthropology, with a concentration in Environmental Sustainability, May 2020 from Southern New Hampshire University. Her passion for food history and culture came out of her early college years as an anthropology student at New Mexico State University in the early 1990s, after reading anthropologist Marvin Harris’s work on cultural food customs and taboos. While cooking and baking have been an interest since childhood, the plan to study food and anthropology became clear thanks, in part, to nutritional anthropologist Deborah Duchon and chef Anthony Bourdain.

As an undergrad, Jen researched and wrote on the history of the noodle along the ancient Silk Road, the influence of breakfast cereal on pop culture, the problem and solutions of world-wide food waste, and focused her capstone on food insecurity in the world of Ethiopian khat farmers. As a massage therapist, she speaks to clients about their food choices as an approach to physical and mental healing. Jen’s downtown Worcester massage office is decorated with beautiful photos of food from around the world.

Jen is excited to begin a new education and career path with an open mind to what awaits her in the food studies realm. She brings along her husband, dog, cat and four hens on this life changing adventure. Jen loves hosting friends and family for feasts, especially if she grew the ingredients. Founded with her husband Chris, Woodstello Urban Farm was created as a fun Facebook page in spring of 2020, to connect with loved ones during the Covid-19 pandemic, with hopes to grow from a backyard garden into a small working farm, homesteading life, and recipe blog.

Food Justice and Prison Abolition

Gastronomy student Danielle Jacques calls on the community to sign this petition, written by BU Students Against Mass Incarceration, demanding that the university cuts ties with Aramark, one of the largest food service contractors in the country which services state and federal prisons as well as BU dining halls.

By Danielle Jacques

At first glance, the two topics in the title of this post may appear to have little to do with one another. Those of us who study the world through food may contend that the issue of food and prisons is peripheral rather than central to our discipline. On the contrary, we believe that our research has historically ignored the integral role of the carceral state in our food system, and that any world where the values of food justice are to succeed on a societal scale is necessarily a world without prisons.

The US prison system is hardly a few steps removed from its roots in slavery. In the wake of the Civil War, the convict lease system filled southern plantations with the free labor of formerly enslaved African American men. Though the program officially ended in 1910, both states and private companies continue to profit off the labor of incarcerated men and women, who are disproportionately black and brown. The recent wave of anti-immigration policies, which have increased hostility towards undocumented farmworkers, has also increased use of prison labor in agriculture throughout the US. As Reese and Carr point out in their recent Civil Eats piece, a just food system requires abolishing the “plantation-paradigm” that was built into our agricultural economy hundreds of years ago.

Research that unpacks the ills of industrial agriculture in the US often does not sufficiently acknowledge that our food system rationalizes incarcerated individuals as subhuman, and therefore disposable. But incarcerated people are not simply units of labor, producing the food that feeds this country for free. As human beings, they must also eat. And somehow, state and federal prisons with collective budgets of over $8.5 billion per year get away with feeding a population of 2.3 million incarcerated people for less than $2, per person, per day.

This is where Aramark comes into the picture. In Prison Food in America, Camplin details the business of feeding prisoners. Private contractors like Aramark have become popular in both federal and state prisons, with prison populations at as much as 137% capacity, because they promise to cut down both work and budgets for administrators. Since contracts are negotiated in advance, Aramark profits more by cutting food costs to the absolute bare minimum. And since there are no official food safety or nutritional protocols in prisons, there is no accountability.

We hear about the foods that people suffer through in prison anecdotally. Accusations of maggots, mice, and feces in Aramark’s meals have made headlines in recent years. “There's no imagining the cartoonish dishes that landed in front of us, like bologna soup” writes Stephen Katz. Camplin highlights an instance where portion sizes were reduced from two pieces of bread and a spoonful of vegetables to one piece of bread and half a spoonful. A woman who is five months pregnant eats plain, cold noodles for the fourth day in a row. Cafeterias run out of milk and soda is watered down. Even still, some prisons have reduced the number of meals per day from three to just two.

According to Al Gordon, who worked in an Aramark-run cafeteria while incarcerated, “you could eat six portions like the ones we served … and still be hungry. If we put more than the required portion on the tray the Aramark people would make us take it off. It wasn’t civilized. I lost 30 pounds. I would wake up at night and put toothpaste in my mouth to get rid of the hunger urge. The only way a person survived in there was to have money on the books to order from the canteen, but I didn’t have no money. It was especially bad for the diabetics, and there are a lot of diabetics behind bars.”

Given that environmental racism causes chronic diseases to disproportionately affect the same communities that are over-policed in this country, this example illustrates some of the layers of violence perpetrated against black Americans through food. Furthermore, according to Conley and de Waal, systematic food deprivation as a form of punishment, which has become the status quo in our prisons, qualifies as a “starvation crime.” Until Boston University cuts ties with Aramark, our tuition dollars will continue to fund these abuses.

But Aramark is only one piece of the ever-expanding prison-industrial complex, which, in the face of opposition, has adapted at every turn to meet the demands of its administrators and stakeholders. In 2018, for example, NPR broke the story of an Alabama county sheriff legally syphoning off $750,000 from his county’s prison food funds to buy a beach house. The “keep and retain” law, which dates back to the 1930’s, effectively incentivized cutting the costs of feeding prisoners by freeing up any savings from the food budget for the sheriff’s personal use. Outrage ensued, and in 2019 the law was changed, prohibiting sheriff’s from keeping the leftover money for themselves. But earlier this year, two counties in Alabama succeeded in amending their local constitutions in order to reinstate the law.

There is no question that every link in the prison-industrial food chain is, by design, exploitative and inhumane. A business model that incentivizes starving people for profit cannot be reformed. It must be abolished. For this reason, fighting for food justice means demanding nothing short of prison abolition. But as Reese and Carr point out, “as a terrain of struggle, abolition is as much about building the institutions, relationships, and worlds we want to live in as it is about dismantling those we reject.” It takes bravery and imagination to create a world that has never existed, but this is precisely the urgent and necessary work that must be done.

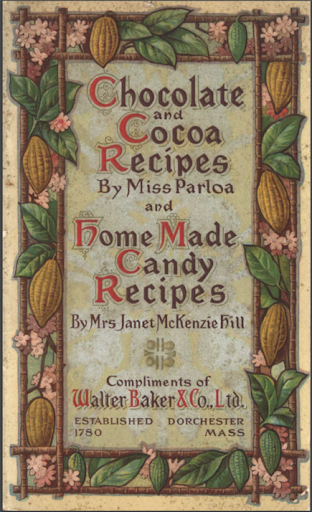

Course Spotlight: Cookbooks and History

What can cookbooks and recipes tell us about an individual? A community? A culture? What does the language of the recipe say about systems of knowledge and ways of thinking about the world? The movement of ingredients and food technology? The transmission of cooking knowledge? Does the analysis of historical cookbooks have contemporary applications?

In the “Cookbooks and History” course, Dr. Karen Metheny will help students consider these questions through a survey of historical cooking texts and in-class exercises. Students will examine cookbooks as a source of culinary history and a window into the changing material culture, practices, spaces, and relationships associated with food preparation and consumption. In addition, students will examine cookbooks and recipes as social documents that reveal the presence of social and economic hierarchies, networks and alliances, and political, economic, and religious structures. They will also examine these documents as cultural texts that reveal the construction of ethnic, gendered, and other identities. Students will study and analyze a selection of cookbooks from different historical periods and geographic regions leading to a final project and paper.

This class will meet on Monday evenings, from 6 to 8:45 PM, starting September 14th. The course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Please contact gastrmla@bu.edu for more information.

Food & Visual Culture: Student Photography

Gastronomy students in the Summer Session course, Food & Visual Culture, had the pleasure of taking a virtual field trip to food photographer, Nina Gallant's studio. Nina explained the contemporary food photography workflow process, and students were able to witness and engage in a client-driven project.

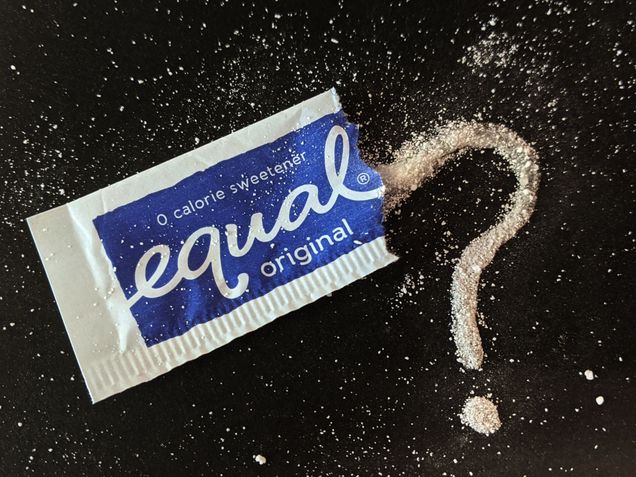

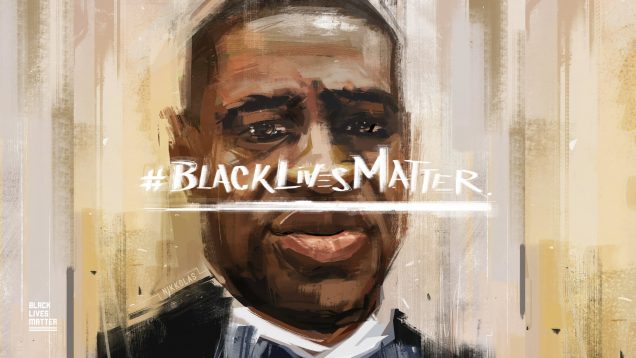

Nina then gave the students a challenge: "Create a message using food. Use this time and space to bring focus to a word or words that respond to the crazy world we are currently living in. You can spell a word or phrase, or simply create a still life using food and non-food items to express your idea, emotion, memory, daydream, or message. Use this assignment as a time and space to create a response to the zeitgeist we are participating in. Consider this photo an album cover for your life right now."

Here are some of the beautiful and thought-provoking images the students styled and photographed:

Since being quarantined, I have developed a deeper relationship with the concept of home. I wanted to create an image that reflected the mood and atmosphere I try to foster in my home. Inspired by 17th century Dutch still life paintings, home, to me, is a little bit moody and a place to reflect, recharge and appreciate small details like late afternoon light coming through the window or brown speckles on a ripe pear.

Anonymous woman: Quarantine Cooking

This photo attempts to represent the stress, anxiety, loneliness, and unpaid labor many people, especially female identifying individuals, have been burdened with during COVID-19 quarantine.

Pictured inside the pot, a photo of an unnamed protestor by John Minchillo/AP Photo.

This photo derives from less of a concrete idea, and more of a sensation. The pairing of coconut milk and chilis has marked my quarantine cooking endeavors, and one night as I listened to stories of the Black Lives Matter protests around the world, my face began to burn. I had touched it with the same hand I used to drop chilis into a pot of coconut milk and fish. In response, I thought of the countless images of protestors getting tear-gassed around the country, and how their eyes, throats, and skin burned as fellow protestors tried to soothe their pain, pouring milk and frothy sodium bicarbonate mixtures down their faces. In response to the tear-gassing of protestors (peaceful or otherwise) and the recent spotlight on the US’ oldest pandemic (white supremacy), I created this photo to explore the ideas of discomfort, control, white privilege, and as many of classmates pointed out, horror. I don’t think I’ll ever settle on one ‘meaning’ for it; with each time I view this image, its message changes, evoking all kinds of discomfort on a personal and societal level.

In response to the recent protests and uprisings against systemic racism and state sanctioned violence, an excuse that I have heard a lot lately is, “It’s only a few bad apples.” However, most people fail to finish this well known phrase: “A few bad apples ruin the whole bunch.” When composing this image, I didn’t have any bad apples on hand, but I used what was available to me. I chose the style of a still life oil painting to bring attention to the way that our society’s values, and what we deem beautiful.

The Perfectly Neglected Carrot

What are the criteria for the fruits and vegetables you buy at the store? Perhaps the unblemished tomato, round firm oranges, or perfectly straight carrot? Unconsciously, many people pick up those that are aesthetically pleasing, yet 40% of it will be left uneaten. In light of the current food insecurities and ongoing fight towards preventing food waste, are you neglecting your food at home?

This photograph utilizes food items to spell a word in order to create double meanings; highlighting the characteristics of the food being photographed as well as societal events. The word, “Rise,” written into the flour, encourages transformation. Rising is not just what bread does, it is also a call to rise up against racist systems and industries to make them more just, diverse, and inclusive.

Course Spotlight: Race, Ethnicity and Food

Dr. Megan Elias will be teaching Special Topics in Gastronomy: Race, Ethnicity and Food during the Fall 2020 semester. This 4-credit course will examine how constructions and experiences of race and ethnicity shape and are shaped by foodways. Both positive and negative definitions of racial and ethnic identities delimit access to and use of different foodstuffs and preparations. In this class we explore these processes, focusing particularly on North America. We will read widely in the literature, paying close attention to intersectional scholarship to understand how limitations related to race, ethnicity, class, religion, gender and sexuality reinforce each other and are also challenged and resisted together. Students will be responsible for participating in and sometimes leading discussion, completing regular writing assignments and designing and completing a semester-long research project.

This class will meet on Wednesday evenings, from 6 to 8:45 PM, starting on September 2nd. The course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Please contact gastrmla@bu.edu for more information.

Course Spotlight: U.S. Food Policy and Cultural Politics

In response to the food-system challenges of pandemic and structural violence, Dr. Ellen Messer has been revising MET ML 721, "US Food Policy and Cultural Politics" to integrate themes from our cutting edge conversations. New formats and materials include integration of new readings and Zoom recordings on food-security issues associated with pandemic and racial disparities, new films and videos associated with struggles for land and food rights in different US locations, podcasts featuring the voices of new community leaders of color, and strengthened sections on gardening and labor issues.

We invite you to read the updated course description:

This course overviews the forces shaping U.S. food and nutrition policies, diets, and cultural politics in the twenty-first century. Special emphases in 2020 include critical responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and nation-wide demands for an end to all forms of racial and ethnic violence and injustice. Course resources and discussions cover the history of U.S. domestic food policy, the Farm Bill, “self-reliance” versus “comparative advantage,” and "sustainability/resilience" versus “efficiency,” and rights-based vs needs-based approaches as drivers of American agricultural, dietary, and food-regulatory policies. All topics and sessions integrate consideration of the multiple ways nutrition policies intersect with health disparities associated with systemic racism, inequalities, and violence. Using Greater Boston as a reference case in point, these discussions critically examine how 2020 nutrition-policy efforts by civil society and government align goals and actions to move forward from hunger to health, and use an “equity lens” to link short-term thinking with longer term outcomes. Concluding sessions probe responses to the question, “Is there a human right to food in the United States?”-- what additional actions are required?

"Food systems," "food chains," and "dietary structure" provide major analytical frameworks for tracing how food moves from farm to table, and the role of local through national government and private for-profit and non-profit non-government institutions in managing these food flows. Within each and considering the food system as a whole, course materials and discussions examine structural violence and persistent inequalities, and the ways policy, practice, and performance mitigate or exacerbate nutritional differences and enlarge or restrict the many voices of those impacted.

Class projects throughout the term explore how the current context affects particular food categories and food value chains, and the ways institutions are developing new strategies and tactics to address recent challenges. Assigned readings about regional food-sheds will draw on Northeast and

New England case studies, but participants joining from a distance will be able to contribute comparative information and experiences from their home locations, where comparable multi-sectoral “food security” and “sustainable food systems” initiatives intersect with “globalization from below.” These policy discussions constructively analyze the multiple layers of regulations and policies, and civil-society organizations and networks, which shape U.S. food systems and food chains at federal, state, municipal, and community levels. They highlight the significance of policy, practice, and performance that influence the varying outcomes and impacts of federal programs at state and local levels.

Objectives:

- Learn the basic structures, operations, and functions of U.S. federal, state, and local food agencies; their connections to non-government food agencies; and the ways these organizations manage official and parallel (supplementary) food systems, more or less effectively, to ensure everyone in the U.S., without discrimination, has access to nutritionally adequate food.

- Engage the challenges of preventing overweight, obesity, and associated chronic disease in the US food and policy context, including challenges to de-link ethnic, racial, and economic disparities from adverse nutritional-health outcomes.

- Be able to use USDA and FDA web-based information platforms for commodity policy analysis and advocacy, and critique associated structural inequalities associated with farm and nutrition programs.

- Understand sustainable food systems models, methods, and materials, as these motivate food-policy councils’ analysis, strategies, and actions; and recent efforts to include more diverse community voices in these processes.

MET ML 721 A1, US Food Policy Cultural Politics will meet on Tuesday evenings, from 6 to 8:45 PM, starting on September 8th in on campus/Learn from Anywhere format. The course is open to graduate students and advanced undergraduates. Non-degree students may also register. Please contact gastrmla@bu.edu for more information.

Black Lives Matter

Dear Gastronomy community,

We write today in solidarity with George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, their families, and those protesting injustice and police brutality across the country who have been met with a brutal, militarized police force. It is with sadness and rage that we add to the growing list of victims David McAtee, a chef and owner of Yaya’s BBQ who was known as “a community pillar,” who “fed the police for free and didn’t charge them nothing,” who was shot and killed by police during protests in Louisville on Monday.

We have heard the calls to action, read the pleas for justice and reform, seen the links to donate and the numbers to call. Perhaps we have opened our wallets or shown up at rallies to demonstrate our support. Perhaps, given the context of an unprecedented global pandemic, we have not been able to do as much as we would like. Perhaps we simply do not know what to do, where to put our time, our resources, and our energy.

We write today to urge our fellow gastronauts to answer these calls, not just today or this week, but in everything that we do as food industry professionals, scholars, and activists.

Let us not forget that the US agricultural industry depends, and has always depended, on the exploitation of marginalized racial minorities. That the hospitality industry was first envisioned in the context of enslavement. That many of Boston’s famed food enterprises, like rum and baked beans, depended on the byproducts of sugar produced by enslaved laborers. That food access is a question of economic justice and housing justice; that food justice efforts must therefore reckon with the fact that racial wealth disparities (the net worth of white Bostonians is on average 31,000 times higher than that of Black Bostonians) are generational and institutional. That land ownership in this country is steeped in anti-Black racist policy, and that Black farmers continue to document discrimination at the local, state, and federal levels of government.

In short, majority white-led food policy, institutions, industries, and even activism, are all involved, directly or indirectly, historically and into the present, in racist systems that perpetrate violence against Black Americans. Those of us with racial privilege, who are over-represented at the highest echelons of our fields, must act, and our action must be ongoing.

As individuals we must:

Read and cite Black scholars, writers, and activists. Across specialties and platforms, we must amplify black voices. In food media and academia alike, we must push back against the dominant discourse that the white experience is the only experience, or the only experience that matters. We must hold ourselves accountable for doing this work every day.

Divest from the prison industrial complex. We must do the research at the personal and institutional level. Are our program funds, our retirement savings, or the investments of our friends and families growing due to the forced labor of disproportionately Black prisoners? Are we aware of all the companies (like Whole Foods) that depend on prison labor? Are we considering this when we “vote with our dollars?”

Restructure and redistribute wealth. This does not mean a one-time donation to a bail fund (still, please donate to a bail fund!). This means monthly payments to organizations who are doing the work to address racial injustice and violence (in its many forms) against Black Americans. This means using our skills, expertise, art, connections, and platform to raise money for these organizations (regardless of the news cycle). This means making the choice to dedicate our free labor to these causes. Please see this piece in Civil Eats for a list of organizations working towards food and land justice for Black Americans.

Vote in the interests of the most disenfranchised members of our community and country. This does not come down to a single election. This involves reading and listening to the voices, stories, experiences, and needs of the most marginalized, and then voting in their interests over our own.

Support black businesses. Please see this list of Black-owned restaurants in Boston, to begin with. All those anti-racist book recommendations? Buy them from Frugal Bookstore.

As a community we must:

Make an official statement that the Gastronomy program is 100% in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, shared on all social media platforms including the Gastronomy Facebook page, Instagram, blog, and email. We must join the list of over 100 Boston University organizations pledging their support of the Black Lives Matter movement by partnering with Boston University’s Black Student Union (UMOJA organization) in their fundraiser.

Compile and promote resources that support the Black community and challenge systemic racism in the food industry, including but not limited to books, podcasts, websites, businesses, etc. Encourage students to utilize these resources.

Require that students and faculty address, analyze, and challenge systems of racism in their coursework. Academia in general, and food studies in particular, is overwhelmingly white. It is our duty to:

-

Address and challenge the predominantly white demographic that this discipline consists of and caters to.

-

Actively reflect on and challenge ways that systems of racism shape representation, power, and authority in the realm of food.

-

Acknowledge and analyze how race affects our positionality and privilege in the understanding of foodways in the classroom, in our work, and in any other platform in which we critically discuss food.

-

Integrate and uplift classwork, readings, speakers, and businesses from communities of color to help dismantle dominant white-centered discourse in academia.

The above are actions that we must all take, individually and collectively, to the degree that we are able, as often as we are able. But this list is not exhaustive. We ask students and faculty to respond with one action item, no matter how small, that they will be taking to address racism in their work and move towards a discourse of anti-racism in food studies.

In the words of Audre Lorde, “there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” We cannot remain silent on these issues and ignore the role of racial oppression in our industry. We who love studying and working with food must recognize the institutional, systematic racism embedded in the field and actively work to undo it.

This program’s solidarity is crucial during this time. Please do not choose silence. Stay connected, stay engaged, and stay safe.

Our best,

Elizabeth Weiler

Danielle Jacques

Elizabeth Weiler and Danielle Jacques are candidates for the MLA in Gastronomy

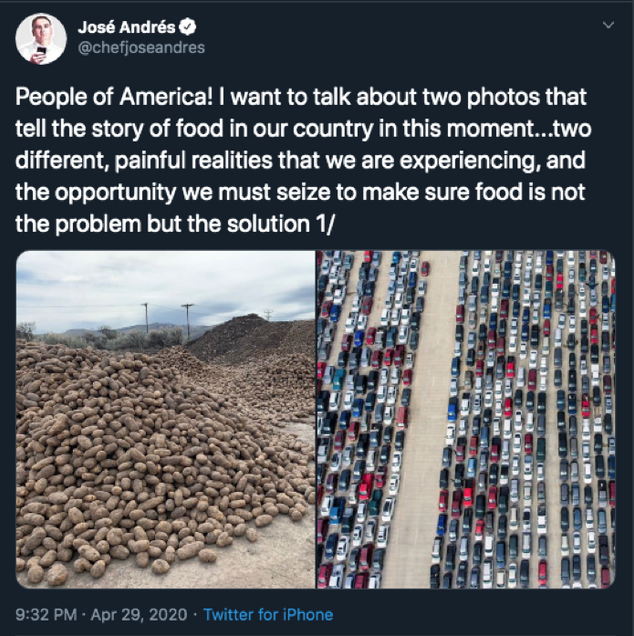

COVID-19 Impact on Global Supply Chains

Gastronomy student Carolyn Holt wrote today's post as part of her work in MET ML 641, Anthropology of Food.

It is hard to overestimate the impact that COVID-19 is having on global supply chains. Awareness of the supply chain effects may have begun with the runs on toilet paper, hand soap, and canned beans at local supermarkets, but more recent accounts of supply chain disruption communicate the scale. Vivid images from all over the country of dairy producers dumping milk and vegetables plowed back into the ground surprised people reading about increased demand at food banks, prompting indignant questions on social media. Many food banks and related food distributors have limited storage capacity for fresh produce (and fewer volunteers than ever), and farms have limited processing capabilities. As Chef José Andrés of World Central Kitchen (which specializes in disaster-response food production and distribution) pointed out on Twitter recently, “we have a food supply chain that we treat as invisible when it’s working...and only notice it when it’s not.”

What is now more obvious than ever is what scholars of famine have known for decades: there is food, and there is hunger; what’s missing is the distribution infrastructure (and political will) to connect producers with eaters. Some have argued that this moment illustrates the need for food sovereignty, and given the record sales of seedlings and seeds (and renewed interest in seed-saving) for home and community gardens it seems that many with access to land agree. But for small-scale farmers, adapting to the crisis has presented a series of challenges, and a steep learning curve.

Farmers who worked with restaurants are finding new ways to reach consumers, as some restaurants convert to grocery stores and some distributors and wholesalers pivot to home delivery. CSA shares have exploded in popularity, but most growth seems limited to farms that had CSA processing and packing capabilities before the pandemic. Some CSAs are arranged by farmers, others by coalitions, and while some are able to offer home delivery others deliver to CSA sites.

Farmers’ markets, which are (generally) better equipped than CSAs to accept federal nutrition benefits like SNAP and WIC, are subject to variable local and state regulation which has left some farmers scrambling. In efforts to negotiate social distancing guidelines, farmers’ markets have innovated: many are now “drive-thru” and some have developed online order and payment capacities to bundle purchases. This article from Boston Magazine outlines some of the options available to those in the city as of a few weeks ago.

I left Boston to shelter-at-home with family in New Hampshire after classes moved online, and a highlight of each week of social isolation has been picking up beautiful mushrooms, parsnips, and salad greens from Longview Farm’s one-at-a-time, self-service farmstand. In an effort to connect New Hampshirites to local farmers, the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension began developing the New Hampshire Farm Products Map, which went live a few weeks ago. The Map not only includes farm locations and crop listings, but employment opportunities and non-food items like compost, hay, and cut flowers. As spring finally comes to New Hampshire, I am looking forward to stopping by Owens Truck Farm and learning about other local producers. Other local resources include the New Hampshire Food Alliance and the Facebook pages of farmers markets.

In Everyone Eats, E. N. Anderson notes that historically, “shifts in foodways often come from ecological or economic changes,” (Anderson 2014, 109). I am hopeful that the attention to the failures of our global food systems prompted by COVID-19 will translate into renewed connection with and appreciation for local food systems and the people who create them. Whether the capacity- and community-building facilitated by innovative responses to global supply chain disruption has staying power remains to be seen.

Works Cited

Anderson, Eugene N. 2014. Everyone Eats: Understanding Food and Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Can wine be chewy? Understanding mouthfeel in our perceptions of taste

This post, by Gastronomy student Amy Johnson, is part of our series from students in MET ML619, the Science of Food and Cooking.

“So this one is a bit of a trust fall,” a blonde waitress explains to me. I sit idly, my curiosity intrigued. “It’s punchy, grippy, but definitely one of my favorites.” She carefully pours the liquid into the thin-framed wine glass directly in front of me.

As the waitress walks away, I hear snickers from my partner. “Grippy?” he asks with a cocked eyebrow. He watches me swirl the red inky liquid in its glass, take a sip, and nod approvingly — his eyebrow still raised in question.

This “trust fall” is actually a glass of Nebbiolo, a red wine native to the Piedmont area of Italy. It harbors some common taste descriptors such as rose and black cherry, coupled with leather, clay pot, and star anise. As my taste buds perceive these flavors, I attempt to determine the wine’s grippy-ness. It is, perhaps, a combination of ethyl phenol and vinyl guaiacol. These compounds are joined together with the molecules commonly found in an oak barrel fermentation, which contains lactones (or is that benzaldehyde?) and is thus digging into my taste receptors, drawing out its moisture. I second guess myself — I’m detecting octenol, not benzaldehyde!

It’s all quite dizzying, no? Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to welcome you to the world of wine. In this lesson, we’ll discuss the role of mouthfeel in our perception of taste. Follow along, and feel free to ask questions if you need to.

Before we begin, it's important to note the differences in mouthfeel versus taste. Though the act of perceiving mouthfeel is typically done in conjunction with taste, it is a separate sense. Wine experts often reference mouthfeel in blind tastings in order to distinguish a wine’s unique characteristics; it is not uncommon to hear the words chewy, fleshy, or grippy mentioned during a wine tasting among top sommeliers. As Wine Spectator’s glossary of terms explains, “Mouthfeel is influenced by wine components, as acidity can be sharp, alcohol can be hot, tannins can be rough and sugar can be thick or cloying.” This type of tactile vocabulary allows sommeliers to discern one wine from another. But confusion ensues for the novice drinker who attempts to understand that a liquidus substance, such as wine, can have textural elements.

However, when these descriptors are applied to more everyday products, the lines aren’t so blurred. The typical wine novice might be stumped at the difference between a wine with viscosity and a wine that’s astringent. Yet this same consumer may shamelessly dump creamer in their coffee while scuffing at the idea of drinking black coffee. Why? Because they enjoy the viscosity, or “weight,” of the added cream and dislike the bitterness associated with black coffee. Cream adds body to the caffeinated liquid, cutting through its otherwise tannic qualities. This is how we can perceive the mouthfeel of liquids, and ultimately identify perceptions of taste.

Another way of understanding mouthfeel in its relation to taste is to focus on the wine’s components. For most white wines, this is acidity, and for most red wines, this is tannins. Tannins are astringent compounds that grip at the sides of your mouth, drying out the taste receptors. Acidity is a bit more linear in its description, partly because we have all experienced the zing! of a fresh orange. Consumers can also identify acidity in different scales. For example, most consumers prefer the taste of fresh oranges, some might also prefer fresh grapefruit, and almost no one enjoys biting into a lemon. These varying levels of acidity can give wine its crispiness, another category of mouthfeel. In an article titled The Indescribable Texture of Wine, wine writer Eric Asimov notes, “Too much acidity and a wine can feel harsh and aggressive. Too little and it feels flabby and shapeless. During the making of a wine, the acidity can evolve from the crispness of malic acids in the direction of softer lactic acids. Interestingly, lactic acids often provide a creamy texture to a wine.”

Thus far, we have identified flavor, viscosity (weight), tannins, acidity, crispness, and even creaminess. But arguably the most important, and most difficult to comprehend, is the discussion of a wine’s astringency.

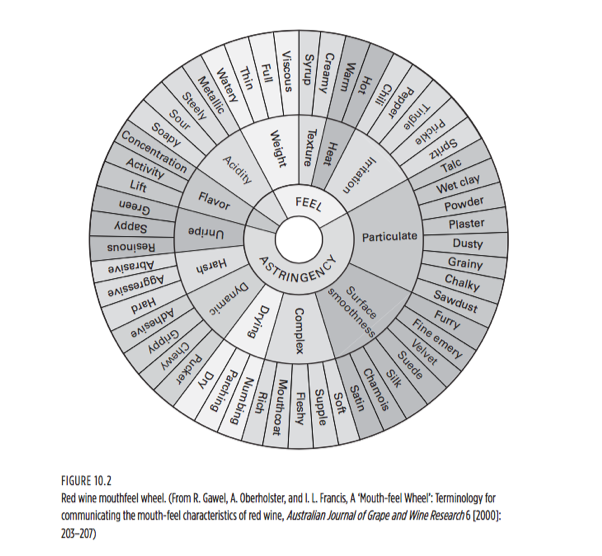

As noted in the red wine mouthfeel wheel developed by Gawel et al., astringent-like descriptors make up more than half of the terminology employed in wine tasting. Astringency is particularly important in the role of mouthfeel as rougher, drier tannins can lead to the perception of a wine’s viscosity.[1] These tannins coat the lubricating proteins in our saliva, forming little aggregates that make the saliva feel rough rather than liquidus. McGee (1987) summarizes this sensation best by stating, “This dry, constricting feeling, together with the smoothness and viscosity caused by the presence of alcohol and other extracted components, create the impression of the wine’s body... In strong young red wines, the tannins can be palpable enough that ‘chewy’ seems a good description. In excess, they are drying and harsh.”

As noted in the red wine mouthfeel wheel developed by Gawel et al., astringent-like descriptors make up more than half of the terminology employed in wine tasting. Astringency is particularly important in the role of mouthfeel as rougher, drier tannins can lead to the perception of a wine’s viscosity.[1] These tannins coat the lubricating proteins in our saliva, forming little aggregates that make the saliva feel rough rather than liquidus. McGee (1987) summarizes this sensation best by stating, “This dry, constricting feeling, together with the smoothness and viscosity caused by the presence of alcohol and other extracted components, create the impression of the wine’s body... In strong young red wines, the tannins can be palpable enough that ‘chewy’ seems a good description. In excess, they are drying and harsh.”

Breaking it down further, we can begin to dissect my aforementioned glass of Nebbiolo. “Punchy” indicates the wine’s acidity levels, noting its youth, as the acid is strong enough to “punch” the inside of the mouth. Fermentation in oak barrels would lead us to the wine’s “grippy” qualities, in that it is, quite literally, gripping to the taste receptors. As for a wine that's chewy, we look towards its dynamic and astringent qualities, as in, “Let me chew on this for a minute before I make a decision.”

Indeed, it’s a bit of a trust fall.

Bibliography

Asimov, Eric. "The Indescribable Texture of Wine." The New York Times. January 10, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/10/dining/the-indescribable-texture-of-wine.html.

Gawel, Richard, A. Oberholster, and I. Leigh Francis. "A ‘Mouth-feel Wheel’: Terminology for Communicating the Mouth-feel Characteristics of Red Wine." Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 6, no. 3 (2000): 203-07. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2000.tb00180.x.

"Glossary: Wine IQ: Wine Spectator." WineSpectator.com. https://www.winespectator.com/glossary/index/id/GL_mouthfeel.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking the Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Allen & Unwin, 1987.

"The Real Difference Between Flavor vs Taste." Wine Folly. March 14, 2016. http://winefolly.com/tips/taste-vs-flavor-vs-aroma.

Shepherd, Gordon M. Neuroenology How the Brain Creates the Taste of Wine. Columbia University Press, 2017.

Wang, Qian Janice, and Charles Spence. "A Smooth Wine? Haptic Influences on Wine Evaluation." International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 14 (2018): 9-13. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2018.08.002.

[1] Shepherd, Gordon. 2017.

SPAM

Here's another post in our series from Dr. Karen Metheny's Anthropology of Food class, by Gastronomy student David Ginivisian.

SPAM. When discussing canned meats, SPAM is arguably in a class by itself. Introduced domestically in 1939 as a convenient and affordable food, it has risen to an unlikely iconic status.  The recognizable cans stacked on market shelves evoke a Warholian image. While there are other canned meats, SPAM reigns supreme over this legion of processed proteins. The option to purchase a shelf-stable meat product is beneficial, especially in our current state, offering both economical and nutritional value. Recent sequestering has led to many of us having extra time to cook at home while becoming more resourceful and creative in the kitchen. With pantries being stocked throughout the world for the potential long haul, the crisis provides opportunity for its continued culinary ascent in popularity.

The recognizable cans stacked on market shelves evoke a Warholian image. While there are other canned meats, SPAM reigns supreme over this legion of processed proteins. The option to purchase a shelf-stable meat product is beneficial, especially in our current state, offering both economical and nutritional value. Recent sequestering has led to many of us having extra time to cook at home while becoming more resourceful and creative in the kitchen. With pantries being stocked throughout the world for the potential long haul, the crisis provides opportunity for its continued culinary ascent in popularity.

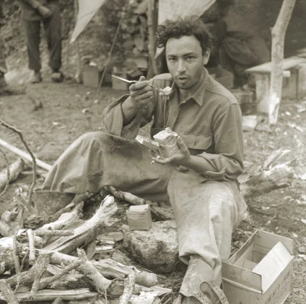

The history of SPAM reveals a wondrous, almost unimaginable tale, traversing the globe with the U.S. WWII armed forces. And just like it provided valuable nutrition for the U.S. G.I.s, SPAM is, once again, at the ready to help get through this current world crisis. With over 15 variations, this spiced pork product, with global reach, is now welcomed into the cupboards and cultures of 44 countries.

The history of SPAM reveals a wondrous, almost unimaginable tale, traversing the globe with the U.S. WWII armed forces. And just like it provided valuable nutrition for the U.S. G.I.s, SPAM is, once again, at the ready to help get through this current world crisis. With over 15 variations, this spiced pork product, with global reach, is now welcomed into the cupboards and cultures of 44 countries.

Worldwide interest and creative marketing have given SPAM a life of its own, well beyond the shelfspace in global supermarkets. In addition to the multiple varieties, there is merchandise, memorabilia, and subculture with a vast interest for all things SPAM. Certainly, SPAM is not the only food with its own product branding strategy, Instagram account or annual street festival, but how many canned goods can you name that have a boulevard named after them? Or their own museum?

Worldwide interest and creative marketing have given SPAM a life of its own, well beyond the shelfspace in global supermarkets. In addition to the multiple varieties, there is merchandise, memorabilia, and subculture with a vast interest for all things SPAM. Certainly, SPAM is not the only food with its own product branding strategy, Instagram account or annual street festival, but how many canned goods can you name that have a boulevard named after them? Or their own museum?

It is rare for such attention and hoopla to be associated with a convenience food. Despite its notoriety, versatility and popularity, SPAM is decidedly not for everyone. I am on the side of the latter. Never a staple in my Mother's kitchen, I can only recall sampling the product once. My college roommate was a big fan. Spurred on by his high praise, I tried it sliced and seared in a sandwich. Meh. Never since has there been a desire, need, or reason for me to include it in a recipe or meal.

It is rare for such attention and hoopla to be associated with a convenience food. Despite its notoriety, versatility and popularity, SPAM is decidedly not for everyone. I am on the side of the latter. Never a staple in my Mother's kitchen, I can only recall sampling the product once. My college roommate was a big fan. Spurred on by his high praise, I tried it sliced and seared in a sandwich. Meh. Never since has there been a desire, need, or reason for me to include it in a recipe or meal.

While I can appreciate that this canned cube of six simple ingredients is a “go-to” for millions, I just don’t have a use for it. From my perspective as an outsider, SPAM is never the main focus of a recipe. Really a bit player that hijacks existing classics, it is forever attempting to insert itself into the lead role but never able to upstage an original. The plethora of international SPAM recipes including tacos, gyros, sushi is exhausting. All the while, this ingredient hides behind other, more interesting and appealing ingredients - an imposter of other, more legitimate foods. For example, would anyone consider a SPAM-LT to be a true substitute for a BLT? Akin to tofu replacing meat in a vegetarian recipe, SPAM has also oddly become a meat substitute. Seldom uttered in the same breath, does this improbable pair of proteins share more similarity than previously considered?

While I can appreciate that this canned cube of six simple ingredients is a “go-to” for millions, I just don’t have a use for it. From my perspective as an outsider, SPAM is never the main focus of a recipe. Really a bit player that hijacks existing classics, it is forever attempting to insert itself into the lead role but never able to upstage an original. The plethora of international SPAM recipes including tacos, gyros, sushi is exhausting. All the while, this ingredient hides behind other, more interesting and appealing ingredients - an imposter of other, more legitimate foods. For example, would anyone consider a SPAM-LT to be a true substitute for a BLT? Akin to tofu replacing meat in a vegetarian recipe, SPAM has also oddly become a meat substitute. Seldom uttered in the same breath, does this improbable pair of proteins share more similarity than previously considered?

I have two SPAM memories related to 1970s American pop culture. The first is from of an episode of M*A*S*H. In this television dramedy about life in a Korean war U.S. hospital camp, Hawkeye, played by Alan Alda, creates a “SPAM lamb” in order to spare a real lamb from being served as the main course for an Easter mess hall dinner with a unit of Greek soldiers. Though I hadn’t noticed when watching reruns as a teen, I now see the producers had the ‘lamb’ set upon a tray of grape leaves next to a bottle of Ouzo and other Greek liquors.

I have two SPAM memories related to 1970s American pop culture. The first is from of an episode of M*A*S*H. In this television dramedy about life in a Korean war U.S. hospital camp, Hawkeye, played by Alan Alda, creates a “SPAM lamb” in order to spare a real lamb from being served as the main course for an Easter mess hall dinner with a unit of Greek soldiers. Though I hadn’t noticed when watching reruns as a teen, I now see the producers had the ‘lamb’ set upon a tray of grape leaves next to a bottle of Ouzo and other Greek liquors.

The second memory is the one made famous by the Monty Python Sketch, aptly titled SPAM. This skit is a must-see glimpse into the comic brilliance of this troupe of British wits. Interestingly, the repeated Vikings’ chants of Spam, spam, spam, spam…. have been credited as the influence for the commonplace use of the word SPAM as reference to junk emails.

The second memory is the one made famous by the Monty Python Sketch, aptly titled SPAM. This skit is a must-see glimpse into the comic brilliance of this troupe of British wits. Interestingly, the repeated Vikings’ chants of Spam, spam, spam, spam…. have been credited as the influence for the commonplace use of the word SPAM as reference to junk emails.

As homage to the irreverent three and a half minute performance, I submit the following recipe:

“Spam, egg, spam, spam, bacon and spam”

Please enjoy the famously funny skit and credits from the 25th episode of Month Python's Flying Circus, which first aired on December 15, 1970.