Can wine be chewy? Understanding mouthfeel in our perceptions of taste

This post, by Gastronomy student Amy Johnson, is part of our series from students in MET ML619, the Science of Food and Cooking.

“So this one is a bit of a trust fall,” a blonde waitress explains to me. I sit idly, my curiosity intrigued. “It’s punchy, grippy, but definitely one of my favorites.” She carefully pours the liquid into the thin-framed wine glass directly in front of me.

As the waitress walks away, I hear snickers from my partner. “Grippy?” he asks with a cocked eyebrow. He watches me swirl the red inky liquid in its glass, take a sip, and nod approvingly — his eyebrow still raised in question.

This “trust fall” is actually a glass of Nebbiolo, a red wine native to the Piedmont area of Italy. It harbors some common taste descriptors such as rose and black cherry, coupled with leather, clay pot, and star anise. As my taste buds perceive these flavors, I attempt to determine the wine’s grippy-ness. It is, perhaps, a combination of ethyl phenol and vinyl guaiacol. These compounds are joined together with the molecules commonly found in an oak barrel fermentation, which contains lactones (or is that benzaldehyde?) and is thus digging into my taste receptors, drawing out its moisture. I second guess myself — I’m detecting octenol, not benzaldehyde!

It’s all quite dizzying, no? Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to welcome you to the world of wine. In this lesson, we’ll discuss the role of mouthfeel in our perception of taste. Follow along, and feel free to ask questions if you need to.

Before we begin, it’s important to note the differences in mouthfeel versus taste. Though the act of perceiving mouthfeel is typically done in conjunction with taste, it is a separate sense. Wine experts often reference mouthfeel in blind tastings in order to distinguish a wine’s unique characteristics; it is not uncommon to hear the words chewy, fleshy, or grippy mentioned during a wine tasting among top sommeliers. As Wine Spectator’s glossary of terms explains, “Mouthfeel is influenced by wine components, as acidity can be sharp, alcohol can be hot, tannins can be rough and sugar can be thick or cloying.” This type of tactile vocabulary allows sommeliers to discern one wine from another. But confusion ensues for the novice drinker who attempts to understand that a liquidus substance, such as wine, can have textural elements.

However, when these descriptors are applied to more everyday products, the lines aren’t so blurred. The typical wine novice might be stumped at the difference between a wine with viscosity and a wine that’s astringent. Yet this same consumer may shamelessly dump creamer in their coffee while scuffing at the idea of drinking black coffee. Why? Because they enjoy the viscosity, or “weight,” of the added cream and dislike the bitterness associated with black coffee. Cream adds body to the caffeinated liquid, cutting through its otherwise tannic qualities. This is how we can perceive the mouthfeel of liquids, and ultimately identify perceptions of taste.

Another way of understanding mouthfeel in its relation to taste is to focus on the wine’s components. For most white wines, this is acidity, and for most red wines, this is tannins. Tannins are astringent compounds that grip at the sides of your mouth, drying out the taste receptors. Acidity is a bit more linear in its description, partly because we have all experienced the zing! of a fresh orange. Consumers can also identify acidity in different scales. For example, most consumers prefer the taste of fresh oranges, some might also prefer fresh grapefruit, and almost no one enjoys biting into a lemon. These varying levels of acidity can give wine its crispiness, another category of mouthfeel. In an article titled The Indescribable Texture of Wine, wine writer Eric Asimov notes, “Too much acidity and a wine can feel harsh and aggressive. Too little and it feels flabby and shapeless. During the making of a wine, the acidity can evolve from the crispness of malic acids in the direction of softer lactic acids. Interestingly, lactic acids often provide a creamy texture to a wine.”

Thus far, we have identified flavor, viscosity (weight), tannins, acidity, crispness, and even creaminess. But arguably the most important, and most difficult to comprehend, is the discussion of a wine’s astringency.

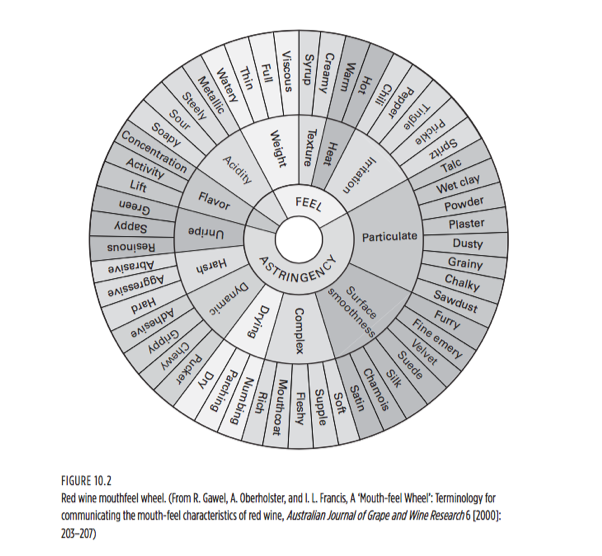

As noted in the red wine mouthfeel wheel developed by Gawel et al., astringent-like descriptors make up more than half of the terminology employed in wine tasting. Astringency is particularly important in the role of mouthfeel as rougher, drier tannins can lead to the perception of a wine’s viscosity.[1] These tannins coat the lubricating proteins in our saliva, forming little aggregates that make the saliva feel rough rather than liquidus. McGee (1987) summarizes this sensation best by stating, “This dry, constricting feeling, together with the smoothness and viscosity caused by the presence of alcohol and other extracted components, create the impression of the wine’s body… In strong young red wines, the tannins can be palpable enough that ‘chewy’ seems a good description. In excess, they are drying and harsh.”

As noted in the red wine mouthfeel wheel developed by Gawel et al., astringent-like descriptors make up more than half of the terminology employed in wine tasting. Astringency is particularly important in the role of mouthfeel as rougher, drier tannins can lead to the perception of a wine’s viscosity.[1] These tannins coat the lubricating proteins in our saliva, forming little aggregates that make the saliva feel rough rather than liquidus. McGee (1987) summarizes this sensation best by stating, “This dry, constricting feeling, together with the smoothness and viscosity caused by the presence of alcohol and other extracted components, create the impression of the wine’s body… In strong young red wines, the tannins can be palpable enough that ‘chewy’ seems a good description. In excess, they are drying and harsh.”

Breaking it down further, we can begin to dissect my aforementioned glass of Nebbiolo. “Punchy” indicates the wine’s acidity levels, noting its youth, as the acid is strong enough to “punch” the inside of the mouth. Fermentation in oak barrels would lead us to the wine’s “grippy” qualities, in that it is, quite literally, gripping to the taste receptors. As for a wine that’s chewy, we look towards its dynamic and astringent qualities, as in, “Let me chew on this for a minute before I make a decision.”

Indeed, it’s a bit of a trust fall.

Bibliography

Asimov, Eric. “The Indescribable Texture of Wine.” The New York Times. January 10, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/10/dining/the-indescribable-texture-of-wine.html.

Gawel, Richard, A. Oberholster, and I. Leigh Francis. “A ‘Mouth-feel Wheel’: Terminology for Communicating the Mouth-feel Characteristics of Red Wine.” Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 6, no. 3 (2000): 203-07. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2000.tb00180.x.

“Glossary: Wine IQ: Wine Spectator.” WineSpectator.com. https://www.winespectator.com/glossary/index/id/GL_mouthfeel.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking the Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Allen & Unwin, 1987.

“The Real Difference Between Flavor vs Taste.” Wine Folly. March 14, 2016. http://winefolly.com/tips/taste-vs-flavor-vs-aroma.

Shepherd, Gordon M. Neuroenology How the Brain Creates the Taste of Wine. Columbia University Press, 2017.

Wang, Qian Janice, and Charles Spence. “A Smooth Wine? Haptic Influences on Wine Evaluation.” International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 14 (2018): 9-13. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2018.08.002.

[1] Shepherd, Gordon. 2017.