Spotlight on…Rich Saitz

Richard Saitz, MD, MPH, Principal Investigator of Boston ARCH and Chair of the Department of Community Health Sciences at the Boston University School of Public Health

As told to URBAN ARCH Admin Core staff, May 2016

l-r: Margo Godersky, Rich Saitz, and Alicia Ventura

How did you become involved in alcohol use and HIV research?

In my medical training, I saw lots of patients in the general hospital who had alcohol-related issues. It was one of the most common things that we treated people for, but when they were discharged, there didn’t seem to be any plan, and there certainly wasn’t any talk about evidence- or research-based treatments focused on their alcohol use disorder. That didn’t make any sense to me, so that’s how I got interested in looking at literature and doing research to address alcohol use disorders.

During my clinical training when I started my internship, the first paper published on AZT came out. During my residency, I saw many sick people dying from HIV infection and AIDS, because it was just the beginning of effective treatments. There definitely was some overlap with substance use disorders, mostly around injection drug use as a risk factor, but I didn’t focus on that for a few years. Within the first five years of my research career, because I was working with Jeffrey Samet, we proposed a cohort study focused on HIV and alcohol. He was such a great mentor that he made me the co-Principal Investigator of that cohort, even before it was an official title at NIH.

You and Jeffrey Samet have collaborated on many studies over the years, how is Boston ARCH different?

Boston ARCH is different because it is a cohort study. We have done a lot of health services intervention studies focused on people with substance use disorders and different ways of integrating care for substance use disorders and mental health into general health care settings. Boston ARCH is similar to the original HIV-LIVE cohort study we did, in that it addresses a serious medical condition as well as substance use disorders, but it also has a couple of unique features. Although we are very interested in the alcohol component, this cohort is affected by multiple substances. I see that as a real world cohort. This is the way that we find folks with HIV infection in this particular subpopulation; they are substantially affected by other drugs. It’s a little messy from a research perspective, because people are affected by multiple risk factors, but if we are ever going to understand real people in the real world, this is the way we have to look at it.

What is the most interesting thing you’ve learned from Boston ARCH?

One of the more interesting things is that we haven’t really found much of a relationship between alcohol consumption and bone density. We are beginning to see a signal for alcohol use and bone-related consequences, like fractures. That might be because of alcohol’s effects on bone, but it might also be because of alcohol’s effects on injury. However, when we isolate the effect of alcohol use on bone density we haven’t found too much. It may be that this population is affected by so many other risk factors such as other drugs they are using and HIV infection itself. It’s not that bone density and osteopenia and osteoporosis aren’t important problems in this cohort, as more than 2/3 of people in this cohort have osteopenia and osteoporosis. Fractures are also common in this population, so it may just be that while alcohol might have an effect on bones, and it certainly has an effect on injury, its effect may not be able to be disentangled from some of these other multiple risk factors.

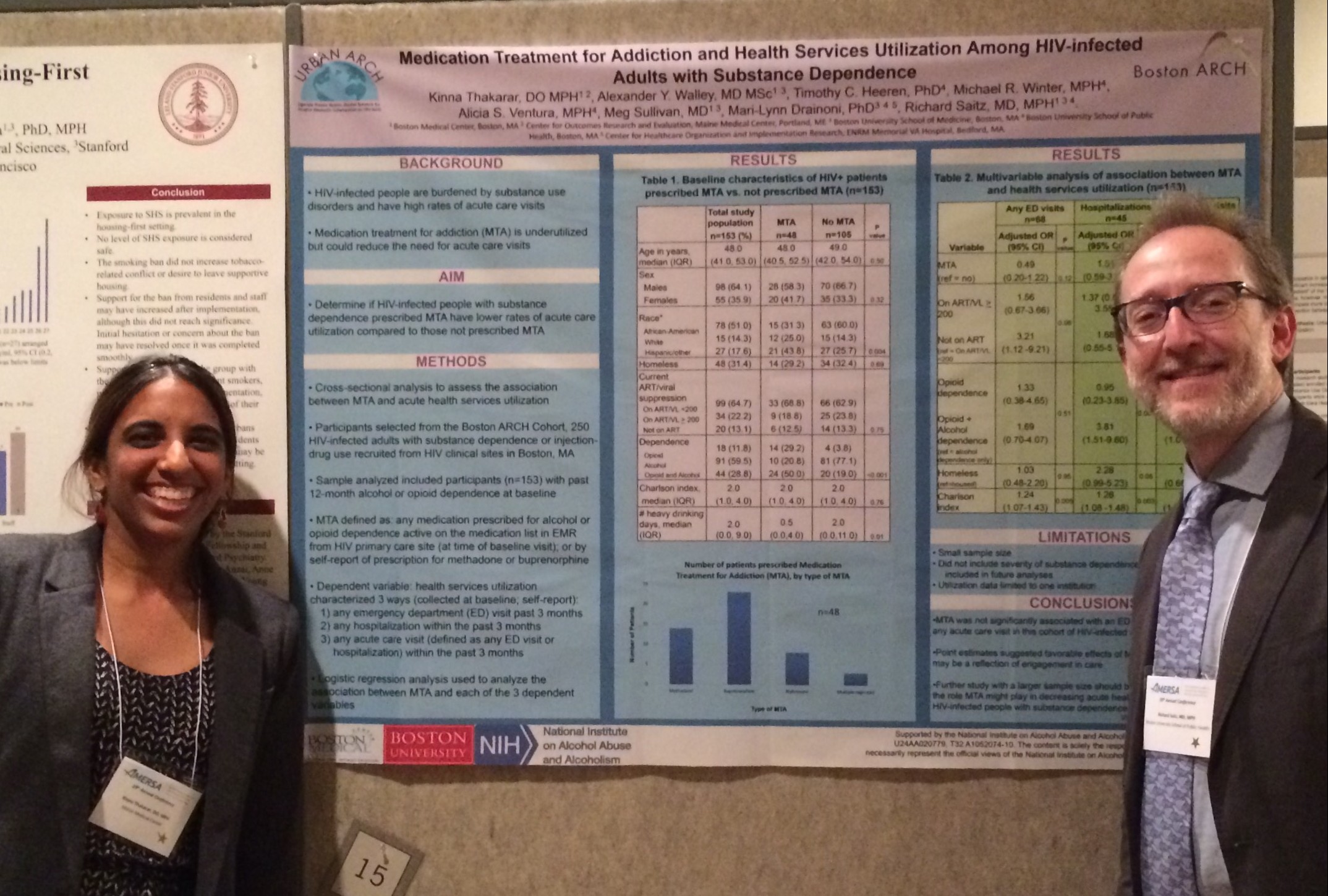

l-r: Kinna Thakarar and Rich Saitz at the 2015 AMERSA Conference

During your time as PI of Boston ARCH, you took on a new role as the Chair of the Boston University School of Public Health’s Department of Community Health Sciences, how has that influenced your work as a clinical investigator?

This position was in my future 20 years ago, and that’s because as a general internist my focus was often prevention or population health to begin with, so it made sense. I can’t say that it changed my trajectory and what I’m studying, but in working with a new group of faculty it’s expanded my focus beyond my general internal medicine colleagues. I work a lot more now with epidemiologists, people with social science skills, and more qualitative research. I now also mentor people who are not physicians and who are using mixed-methods for research, and we’ve brought them on board to do secondary analysis on Boston ARCH. Overall, it has impacted the kind of work that I’m doing by expanding across methods and going across disciplines.

You and your team are well known for excellent research participant follow-up rates, what is your secret?

The secret sauce is really good research assistants. Hiring research assistants who are able to quickly establish relationships with other human beings. The other part is paying explicit attention to things that are well-known to affect research follow-up rates but maybe not used by all. One method we’ve used for years that still seems to be effective is sending a Fed-Ex when you can’t get ahold of them. Many of our participants have never received a Fed-Ex with their name on it, so this elevates it. Another technique I learned many years ago was to always get the mother’s phone number. Mothers are particularly important in some ethnic sub-group communities, and they’re important in all human families, but sometimes the mother is the only person left in the social structure. If you get their number, they know where the person is. It’s the information that you collect up front that you can then use later to track people down, and then take advantage of that relationship you establish early on. We have sophisticated tracking systems and we compensate participants appropriately. We use medical records appointment systems in real time to meet people when they appear. And we always get special HHS and IRB approval to follow-up with participants even if they become incarcerated.

What are you most excited about for the future of Boston ARCH and URBAN ARCH in the next five years?

The most exciting thing to me about URBAN ARCH is the ability to have a research platform that has participants who are well characterized across a number of domains, multiple times, who are a relatively understudied population, and who are complicated so we can answer a wide range of questions. I’m excited about being able to broaden from just looking at bone density to looking at an issue that is of importance to not only people with HIV infection as they age, but also to people in this large sub-group of people with HIV infection who are affected by multiple substances. Those issues are around falls, fractures, and how medications, drugs and alcohol affect them, and I think we’ll be able to answer a lot of core questions within this important area of risks and concerns.

Tell us one surprising thing about yourself. What do you like to do in your free time?

I was the assistant music director for Fiddler on the Roof when I was a senior in high school. For some performances, I got to conduct the orchestra; It’s complicated, because you have to direct both the orchestra and people on stage. I did a lot more music than I do now, so in my free time, I’d like to do more music. But I spend a fair amount of my free time with my daughters – taking them to horseback riding, violin lessons, ballet, and Red Sox games.