Ethics and AI Startups

James Bessen, Stephen Michael Impink, Lydia Reichensperger, and Robert Seamans

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is already transforming the economy and is anticipated to change how employees work and organizations function. At the same time, AI production is fraught with unresolved ethical challenges ranging from data privacy to algorithmic bias to the overemphasis of prediction accuracy. Firms have little guidance from regulators or judicial precedent on these matters, necessitating them to balance many of these trade-offs between ethical issues and data access on their own. For young firms, these choices have the potential to shape their funding and growth prospects. The third-annual TPRI survey of AI startup firms reports that 58% of respondents have established a set of ethical AI principles. In a recent paper, we analyze how these ethical policies are invoked and impact their business outcomes and explore heterogeneity in adopting firms.

Though governments have been slow to act, large technology firms have set policies that provide a rubric of how their firm views the risks of AI production. Often these policies align with their business models and exist to help firms manage the risk of their employees or partners inappropriately or unethically using training data or AI. There is limited information about how creating and adhering to ethical AI policies is connected with performance, even for these larger firms. There is less information about how adherence to ethics policies correlates with AI startup performance, which heavily depends on initial training data.

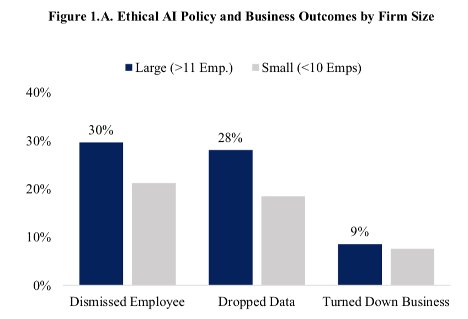

Moreover, simply adopting ethical AI policies does not mean that these startups necessarily act on them. As such, we ask respondents about business decisions they made based on adherence to their policies. Figure 1 shows that of startups with ethical AI principles, 9% turned down business, 30% dismissed an employee, and 28% dropped training data. So, not all firms that had a policy had encountered a situation where they needed to invoke their policy or, alternately, chose not to take one of these business decisions. Many startups took other actions that favor more ethical use of AI. For instance, many startups made more diverse hires (69%) and considered diversity in selecting training data considering diversity in their selection of training data (46%).

Using Heckman’s Selection Model and CEM (matching), we find that prior funding does not appear to be related to the adoption of principles. However, relationships with technology firms and, particularly, data-sharing relationships with technology firms are positively correlated with policy adoption and use. Given there is a lack of government regulations, these large technology firms may be setting norms in the industry by advising their customers and partners to follow their policies. Startups with a relationship with firms like Amazon, Google, or Microsoft are more likely to establish ethical AI principles. Prior regulatory experience, such as negative experience with GDPR, is positively correlated with ethical AI policy adoption. Startups may have gained certain regulatory adherence capabilities through navigating the same types of complex issues addressed by ethical policies.

These self-imposed policies can be costly and be a particular burden on new and small firms. Some startups may even turn away businesses that could potentially conflict with their ethical guidelines. Yet, these ethics policies may also positively affect business, serving as a signal of a firm adopting the norms of the broader industry, making them a more attractive partner for certain investors or larger firms. These results make clear that AI startups are grappling with ethical issues while they continue to innovate. Moreso, ethical challenges these startups face will only become large as they use more sophisticated algorithms requiring more robust data, while lacking uniform regulatory guidance.