By: Michelle Amazeen

Barbie: Covert Influence and Representation

The billion-dollar blockbuster movie this summer was Barbie. As I prepared to go see it with my mother in July, I reminded myself that I was going to see what amounts to a 2-hour advertisement for a child’s toy, a practice also known as branded entertainment. As a scholar who studies covert influence, I am particularly aware of the goals of this strategy: don’t make the content into an explicit sales pitch but also create positive associations for your brand. While not as insidious as branded content that imitates news, the commercialization of media content – especially content directed at children – has been expanding.

This technique isn’t new. In 1931, the radio drama “March of Time” documented the work of journalists by reenacting famous news events such as the Hindenburg disaster or the disappearance of pioneering aviator Amelia Earhart. In reality, it was actually branded content, produced by Madison Avenue ad agency Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn (BBDO) that was intended to cross promote Time magazine to radio audiences. In other words, it was an ad, just like the Barbie movie.

Watching the movie with this critical mind-set, I found myself enjoying it more than I expected. As a misinformation researcher, I was surprised by the intellectual winks to psychological theories such as Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance and William J. McGuire’s inoculation theory. As one Barbie says to another, “By giving voice to the cognitive dissonance required to be a woman under the patriarchy, you robbed it of its power.” That is, exposing patriarchy will build immunity against it. Alas, just talking about patriarchy doesn’t confer resistance to it. Indeed, most Americans believe there is more work to do in attaining gender equality.

Although I enjoyed the movie, my expertise is not in examining media representations. This expertise is, however, in the purview of the Communication Research Center’s newest Fellow, Dr. AnneMarie McClain. As an Assistant Professor of Media Science, Dr. McClain focuses on understanding how media – and conversations around media – can be used to promote positive outcomes for children and families, especially marginalized children and families. I asked Dr. McClain her thoughts on the Barbie movie, and this is what she shared:

The girl power! The outsmarting of the boys! The nostalgic rollerblades! As a millennial who loved Barbies, there were many elements of the new Barbie movie that struck right to my childhood core. However, as a mother raising small children and an academic who studies representation and identity socialization, it is important to highlight that the film missed some opportunities to be truly expansive in its representation and boundary-pushing.

The film had loud chords of feminism, some progressive commentary on various issues in our real human world, and unflinchingly included a trans Barbie, Barbies with bigger bodies, and dolls of various ethnic-racial identities as just part of the gang. Yet, the film largely stuck to the gender binary: real and fictional worlds of only females and males, rendering nonbinary individuals, gender fluid people, and people of other genders essentially invisible. The theory of invisibility (Fryberg & Townsend, 2008) suggests that without representation, it becomes harder to see yourself positively and to navigate your environments. The film missed moments to capture how the Barbie franchise has inspired people of all genders, not just girls. Importantly, Mattel has a line called Creatable World with dolls that can change their gender expression; featuring those dolls in the film, too, would have more accurately represented the world that we live in — and that we need to celebrate.

Additionally, although the film featured BIPOC Barbie and human characters, the favorite doll of the Latine family was the white so-called “stereotypical Barbie.” This racial element was never addressed. Given concerns about how play may reflect BIPOC girls’ beliefs about their identity (e.g., Sturdivant & Alanis, 2021), this wide-reaching film missed opportunities to explicitly affirm that brown and Black dolls can be favorites, too. Barbieland also had a Barbie-version Mount Rushmore replica, a monument of European settlers carved into the sacred Black Hills of the Lakota Sioux, along with an unnecessary analogy that referenced smallpox harming Indigenous populations. Though these examples were not the center of the film, they could cause harm to Indigenous communities, who are already unfairly and minimally represented in U.S. media (e.g., Leavitt et al., 2015). The film also leaves room for more sensitive language around mental health – for example, it could have avoided using ableist language like “crazy” and “insane” and removed the commercial that makes light of mental health challenges where various conditions like OCD were “sold separately.” The Barbie movie tried to drive home an important message about how girls and women can be anything they want to be, but it could have also more explicitly celebrated another key part of inclusivity as well: that whoever any of us are is already enough, too.

While it might be unfair to demand a summer movie be all things to all people, Barbie’s social failures go beyond identity dynamics.

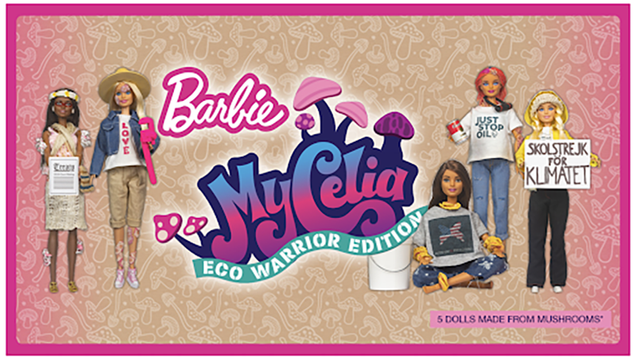

In an interesting postscript to the movie, the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO) – an environmental activist group – employed a classic technique of protest, called culture jamming, to draw attention to the overwhelming use of plastics in society. Given how much oil it takes to produce a single Barbie, more than three cups, the environmental damage caused by the production of Barbies and all of her accessories is concerning to those who care about the environment. The BLO produced a series of press releases purportedly from Mattel that announced its commitment to entirely stop using plastics by 2030 as well as the launch of a new decomposible line of Barbie dolls made from organic materials such as mushrooms, algae, seaweed, clay, and bamboo. At least three national news organizations fell for the influence campaign and published articles about the pledge and new doll line including People, The Washington Times, and Dow News Wire.

In response to questions about the ethics of their culture jamming efforts, a BLO activist stated that, “What we’re fighting against is half a century of misinformation from the plastics industry and from fossil fuel companies and interests that are trying to convince people that recycling is a viable solution to the plastic waste problem.”

Thus, the Barbie movie has been a case study in how covert influence campaigns are being used to both entertain us as well as to hold powerful corporate interests to account.