By: Bridget Fahy

Introduction

Adoption is recognized as a “legal institution that creates a parent-child relationship between an adopting individual or couple and an adopted person.”[1] It a form of child welfare services that has formally existed in the United States since 1851 after the Massachusetts Adoption of Children Act was enacted[2] to promote adoption endeavors and find homes for children within the country. Legally adoption has crafted many agencies along the way trying to streamline the service and allow for the flow of legal processes in order to make certain the adoption is ethically sound and obtains the ultimate goal. The United States was the first country to legally recognize adoption with other countries such as the United Kingdom, not having created legal framework for these particular cases until 1926.[3] The United States has been the number one recipient country of adoptees every year since the practice has existed. It reached its peak in 2004 when 24,000 children were adopted from overseas and brought to the United States.[4] Ten years later in 2014, the U.S. State Department recorded only 5,647 children adopted and received in the United States.[5] This statistic demonstrates a 75 percent decline within one decade. My prerogative throughout this research paper is to highlight International Organizations’ (such as The Hague) role in promoting this decrease in transnational adoptions and why precisely this is beneficial for nations’ domestic social service policy and reduced margin for error in situations involving vulnerable children.

Background

The first recognizably legal intercountry adoption occurred in 1955, when Henry and Bertha Bolt, an evangelical husband and wife from Oregon successfully secured a special act of Congress and began to adopt Korean “war orphans.” This established the first wide scale international adoption agency. Since the inception of legal transnational adoption, began a whirlwind of both positive and negative effects: the positive being a family joint in multiculturalism and love or the negative being a child involuntarily entering a human trafficking network which sought to increase profit and decrease any innate moral obligation to protect children. Privatization of agencies and a lack of stringent legal processes and safeguards for facilitating adoptions, spurred these heinous acts. These occurrences led the Hague to institute the Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption in 1993. Transnational adoption saw its peak in 2004 and since has quite rapidly declined by 74% since. International Organizations such as the United Nations, and the Hague in conjunction with domestic governments have joined forces to curtail such deceitful practices of privatized adoption agencies consequently reducing adoptions between nations at large. Internal adoption rates within countries have also boosted since the pivoting of agencies from global adoption.

Broad Analysis of Negative and Positive Outcomes of Intercountry Adoption

Since the onset of legal transnational adoption, began a whirlwind of both positive and negative effects. The positive outcomes include this multiculturalism of a family symbolic of international relationships, the child receiving a family and a safe space to call home void of poverty, birth parents consenting to adoptive process, and the recipient family becoming the legal protectors of a child. The negative outcomes are comprised of private adoption networks’ disregard for legal channels, lack of consent from birth parents, child laundering, and the most severe outcome being, child trafficking.

Some specific examples of what could go awry in the intercountry adoption process and what has been faced in this market before are as follows:

- Child trafficking/child laundering (defined as a scheme, whereby intercountry adoptions are affected by illegal and fraudulent means, involving child trafficking, the acquisition of children through monetary agreements, deceit, and/or force.

- Suicide amongst international adoptees

- Forced and exploited labor

- Forced prostitution

- Forced or exploitative domestic service

- Forced work on inherent and hazardous industries

- Forcedly taking out different organs [6]

Specific Case Studies of Unethical Quandaries and Legal Concerns Facing Intercountry Adoptions

- In 1994: Romania faced allegations of child laundering. The United States embassy investigated Romanian adoptions and discovered “incidents where Romanian mothers believed that they were merely loaning their children to foreign parents and not relinquishing them permanently.” In addition to this Romanian adoption agencies were accused of profiting heavily off of intercountry adoptions as currency rates allowed for companies to receive payouts from prospective American adopters, in quantifiable lump sums which oftentimes was not utilized for the betterment of the orphanage establishment.[7]

- In 2003, a report by UNICEF was released describing child trafficking and laundering of children on the continent of Africa with regard to intercountry adoption described in multiple sections. [8]

- In 2004, Samoan birth parents explained that the private United States adoption agency called “Focus on Children” had deceived them into sending their children away under the claim that they would “receive an American education and then be returned to the country of origin.” Many children never were and thus began a civil lawsuit which ended in the incarceration of agency owners. [9]

- In 2010, a Russian adoptee whose adoptive parents were from Tennessee wound up sending the child back on a one-way flight to Moscow with a note claiming the boy was “mentally unstable.” After this particular incident, the Russian administration concluded they must internalize adoption as best they can.[10]

Statistical Analysis of the Decline in Intercountry Adoptions

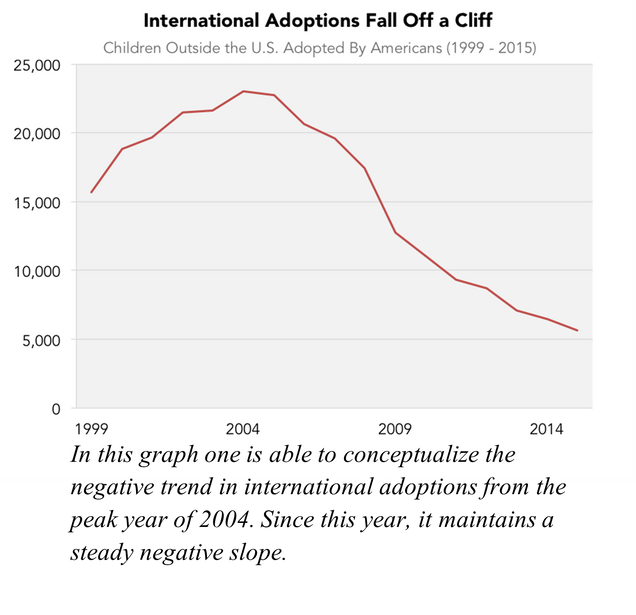

Figure 1[11]

Figure 2[12]

In most graphs you peruse over portraying this global trend, there is no way to really skew it. Intercountry adoptions have become far less pertinent of a practice since 2004, onward. Figure 1, demonstrates the negative slope representative of intercountry adoptions facilitated within the United States. From 1999 to 2004, it maintains a slow but steady positive slope, reaches its peak in 2004, and divots afterwards proving that the decrease in adoptions was a drastic and fast-acting one, presumably spurred on by something other than just “less demand.”

Figure 2 is a depiction of the absolute number of adoptions (and the representative decline percentage rate) in primary recipient countries in 2004 versus 2010. As you can discern, each of these nations reached their highest numbers the legal industry had ever seen, and then plummeted the year succeeding. The year 2014, is indicative of the least amount of intercountry adoptions the world had seen since its legal inception in the mid 1900s.

Guiding Question

Given the reduction in nation to nation adoption rates and slowdown of child laundering within this system, is it probable that internationally recognized laws and international organizations were the impetus behind this shift? Furthermore, can this internalization of adoption processes increase infrastructure of both developed and developing nations?

Hypothesis

Since the dissemination of newfound international policies on transnational adoption (via the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption: 1993), private international adoption agencies and the network as a whole have experienced lower rates of intercountry adoption and worldwide trends towards internal adoption are increasing. In addition to this, child laundering and trafficking have reduced significantly within this particular network, supporting the claim that international organizations not only have sway in bettering privatized adoption agencies, but also in bolstering domestic adoption policies and programs within nations. This shift to domestic adoption due to the Hague’s insistence on intercountry adoption being a “final resort” does reduce harmful outcomes of adoption service providers and enhances infrastructure within the country.

Methodology

Since it is quite clear that statistical evidence is necessary in providing the reader ample intel on intercountry adoption rates, this research paper will be heavily interspersed with statistical analysis acquired from credible sources and sites. Quantitative data will include statistics and graphing to provide absolute numbers and a visual of the negative slope in children migration patterns via the intercountry adoption network. In addition to quantitative data, qualitative data too will be extrapolated from case studies and reading on the subject matter, providing worded evidence of heinous acts committed during the less regulated era of intercountry adoption during the late 20th century. The focal point of this analysis is to sift through newfound legal requirements in transnational adoption mandated by international organizations and see how their application was carried forth throughout privatized adoption agency protocol. In addition to determining the effectiveness of IO mandates, I seek to research domestic policy on adoption, through statistical analysis and qualitative data, to provide information to readers on how, in terms of infrastructure, this could better a nation’s domestic adoptive programs and policies.

Theory

The primary theory structuring the above argument will be liberalism as it is entrenched in the fortification and establishment of apt international organizations for mitigating violent state or privatized forces and overseeing transactions, legal processes, and in this case adoptions on a global scale. With liberalism accentuating international cooperation and the distinguishing of an individual’s well-being as an extension of a state’s well-being, I saw it just to utilize this theory for my research paper. Philosophers such as Immanual Kant helped to drive certain points of the theory home, for myself. Kant elaborated on peace programs being applied to all nations, thus harboring initiatives and ideas for international organizations, such as the United Nations, International Law, The Hague, and other leading international actors.[13] Such programs allow for the cooperation amongst multiple states across borders and secure benefits amongst all. In this case of intercountry adoption, I will be explaining how international organizations (especially The Hague) acted as an intermediary for resolving scandalous crimes impeding upon the rights of children. The lens introduced in this research paper is primarily through the international relations theory of liberalism and the cooperation of multiple nations in maintain their enterprises.

An International Agent: The Hague’s Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect to Intercountry Adoption

With blatant international pressures to mitigate conflict in regard to children’s rights and adoption, The Hague established a convention to determine solutions. With the creation of The Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-Operation in Respect to Intercountry Adoption in 1993, came a universal legal framework surrounding intercountry adoption and a set of guidelines which were encouraged but not required for nations to abide by. The Hague clarified that intercountry adoption should be resorted to if and only if a suitable family has not been found in the country of origin.[14] The main objectives of this convention were as follows…

- to establish safeguards to ensure that intercountry adoptions take place in the best interests of the child and with respect for his or her fundamental rights as recognised in international law;

- to establish a system of co-operation amongst Contracting States to ensure that those safeguards are respected and thereby prevent the abduction, the sale of, or traffic in children;

- to secure the recognition in Contracting States of adoptions made in accordance with the Convention.[15]

By having created these objectives and newfound set of legal framework and ideas to keep agencies up to par, prospective parents of sound eligibility, and make it recognizable within the nations that ratify, The Hague had a mighty task to take on in this particular instance.

The Intercountry Adoption Process (Currently)

The intercountry adoption process became further safeguarded after the Hague’s Convention in regard to intercountry adoption. With 99 nations including the United States, ratifying the efficacy of these moral guidelines, came a slew of new policies and accreditation services to make absolutely certain the agency is operating in the best interest of the child being adopted, and has no ulterior motive. I’ll be primarily discussing the United States new process in intercountry adoption, as assessing every nation’s new intercountry adoption process would be an incredibly lofty task. I will provide examples of the most recognized national laws and moratoriums on intercountry adoption nearer to the end of this paper.

The Official United State Intercountry Adoption document describes in full every detail, nuance, stipulation, and legal document you must heed notice of as a new prospective adoptive parent. It is explained explicitly that “the process varies greatly because it is governed by the laws of the countries where the adoptive parents and the child reside (which in the United States means both federal and state law) and also in which location the legal adoption is finalized.”[16] As it can be inferred, the process of adoption becomes more arduous as the recipient nation must adhere to legal framework in a foreign nation, in addition to the framework employed in the United States. Furthermore, most adoption agencies in the United States and abroad, recognize the requests and desires of the birth parents relinquishing custody of their child, making international interaction between birth parents and adoptive parents, all the more difficult. Dependent on the nation’s laws, the process may require an adoptive parent to spend one year in the country of origin before returning with the child back to the new nation of residency. Uganda is a prime example, of this particular prerequisite as it explicitly states it in its official documents that “under Ugandan law, adoptive parents must reside in Uganda for at least one year. In addition, adoptive parents must have fostered the child in country for at least one year under the supervision of a probation or social welfare officer.”[17]

Following national laws and policies is something an adoptive parent must be acutely aware of, but also must understand that there are international laws to be recognized if the country of origin has ratified the Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. The United States ratified the convention less than one year following its inception, and formally entered into force on April 1st, 2008.[18] With this recognition of the Hague convention came its own interpretation and implementation of national laws catered towards the convention in each nation that ratified it. This accounted for even more safeguarded policies, programs, and services protecting the legal industry from money laundering, deceitful practices, or in the worst case scenario entering human trafficking circles. The adoption of children from “convention countries” determines who is eligible to be an adoptee and who is eligible to adopt. A child who is a resident of a nation who ratified this important treaty, must qualify as a “Convention Adoptee” in order to immigrate to the United States.[19] There are also certain qualifications of a prospective adoptive parent to deem them eligible for the legal position, outlined in form I-800 (Petition to Classify Convention Adoptee as an Immediate Relative).[20] In addition there is another form, I-800A (Application for Determination of Suitability to Adopt a Child from a Convention Country). All of these legal documents and eligibility requirements, are offspring of the Hague Convention and account for a very formal recognition that both the child and the prospective adoptive parents are in the position they should be in, in order to facilitate this adoption.

The Convention’s Impact on National Policies Regarding Intercountry Adoptions

Universal Accreditation Act of 2012

In the year of 2012, the Universal Accreditation Act (UAA) was implemented by the Department of State and other nations included, in an effort to even further follow the Hague Convention on intercountry adoption. This new act states that “adoption service providers working with prospective adoptive parents in non-Convention adoption cases need to comply with the same accreditation requirement and standards that apply in convention adoption cases.”[21] This is an act which essentially deflates the arguments upheld by nations who did not ratify the constitution and promotes compliance on every level of an ASP’s compliance to the usual and safeguarded standards. Its focal purpose is to extend the same rights to the children (involved in adoption processes), in countries of residency which did not ratify the constitution. In this sense, private agencies in non-Convention nations are more compelled to abide by the international set of rules and standards regarding this practice.

Intercountry Adoption Accreditation and Maintenance Entity (IAAME)

The US signed the convention in 1994 and then enacted certain policies in 2008, one primary example being the IAAME or Intercountry Adoption Accreditation and Maintenance Entity which is defined by the Department of State as an organization created for the sole purpose of the accreditation, approval, monitoring and oversight of adoption service providers providing intercounty adoption services.[22] The entity was implemented to get Adoption Service Providers accredited and prove that they have “substantial compliance” to the legal framework regarding intercountry adoptions, transparent financial transactions and a full display of their statements, and eligibility as well as corporate structure with their business running smoothly with little to no legal qualms.[23] The insurgence of this entity’s efforts in United States intercountry adoptions, holds a direct correlation to stringent policy reform on intercountry adoption which makes processes, indeed more difficult, but also safer for children.

Romanian Moratorium of 2004

The Romanian Moratorium of 2004 was another prime example of The Hague and the European Union’s sheer power over the nation’s legislature. Romania had “orphanages” which exemplified communist legacies that children who could not be cared for by familial means, should work for and belong to the federal institution. These residential areas for orphaned Romanian children were meager in supplies and left children living in poor conditions with strenuous daily routines.[24] There was a United States v. Romania debacle had over intercountry adoption where the state of Romania was against, and the United States was vehemently for. This in addition to European Union standards for entrance, prompted Romanian policy to shift. In addition to poor conditions and forced labor, allegations of money laundering and legal disregard were inseparable from the adoption service providers facilitating intercountry adoptions in Romania. This exact issue was a key barrier to the European Union not allowing the nation to join. Romania decided their will to enter the European Union was more substantial than the fight to keep informal adoption agencies committing heinous acts afloat. In 2004, the nation enacted their moratorium, completely banning intercountry adoptions and instead pressuring domestic options.[25] Romania joined the European Union in 2007 and was accepted likely because of their compliance to restructure their policies and sharpen their federal adoption service providers (as private adoption agencies were banned in the nation as of 1991).[26]

International Organizations Capabilities in Bettering Private Institutions and Bolstering Domestic Laws

The gist of this research report is to describe just how powerful the role of an international agent can be, in certain situations such as intercountry adoptions and maintaining sharper and more enforced laws surrounding it. Undoubtedly, the decline in intercountry adoptions was not widely accepted nor enjoyed by many American families, due to the fact it is the number one recipient nation. This nation was the country receiving the immigration influx of children from foreign nations being adopted by parents whose intent was (typically but not an entirely pervasive trend) pure and well-intended. An upstir naturally would occur from these laws and regulations sometimes announced as “onerous” and “time-insensitive” to the matter with which the family was dealing. I believe a key factor in the United States constant push for intercounty adoption (especially from families wishing to adopt internationally), is quite simply that they were sidelined from understanding what adoption agencies both in the country and in the country of origin of the adoptee, were often doing. When international transactions occur, an information flow can be disjointed with all of the different legal channels to be weary of. Under the Universal Accreditation Act of 2012, the United States backed away from allowing individual states or even private agencies to oversee intercountry adoptions and instead pivoted to it being a federal matter.[27] In this way, due to the Hague’s insistence, policies were shifted from limited scopes such as privatized institutions into the hands of the federal law, under the Department of State: Consular Affairs.

Discourse over dismantling intercountry adoptions all together, has been going on since the rapid decline succeeding 2004. Human rights campaigns may argue it maintains a long-held dependency between the global north and the global south that has succeeded years of colonialism or that a “White Savior Industrial Complex” underlies the entire industry.[28] On the absolute other side of the spectrum you may have individuals calling for the reduction in regulation as it only promotes the “longer institutionalization of children in the country of origin”[29] and that adoption needs to be an expedient process. Argument of both opponents and proponents of intercountry adoption, hold validity to a degree but lack a certain realization.

In a Hague Conference on Private International Law in regard to the “Abduction, Sale, and Traffic in Children in the Context of Intercountry Adoption” David M. Smolin, holds arguments which promote intercountry adoption, but only under the safeguarded guidelines depicted in the Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in respect to Intercountry Adoption. Smolin states, “…the best way to develop intercountry adoption as an ethical child welfare practice is to safeguard it against abusive practices” and “…the only way to effectively safeguard intercountry adoption against abusive practices is to carefully analyze those abusive practices.”[30] By safeguarding an institution or a practice, individuals analyze precisely what has gone awry and from there, determine an effective solution. Many fail to see, sometimes due to their own biases or inclinations, how a plethora of different institutions or documents have developed through immense scrutiny from external forces or citizens themselves. The constitution of the United States, is just one of the many prime examples, embellished with its multiple amendments (quite literally defined as a “revision/addition”).

In developing an ethical intercountry adoption, the analysis of challenges and abusive practices, is what will propel the institution and practice to be as sound as it can feasibly be. Institutions such as The Hague made certain to hold those committing malpractices accountable and furthermore design initiatives to ameliorate the intercountry adoption process entirely. Its ratification by most countries compounded with the shift in national policies (predominantly US policies outlined in this paper) illuminate the impact that international organizations can have on individual countries and their legislature. Exemplification of an international agent’s force in promoting newfound policy, is the Romania deciding to ban intercountry adoptions in 2004, in the efforts to display their compliance of The Hague’s Protocol, to the European Union. In this way, they not only sharpen their federal adoption service providers and promote domestic adoption before international, but also are a step closer to being admitted into the European Union. Discordances of adoption process are less likely to be had when most nations are in agreeance with one another. With international organizations being extensions of liberalist theory literature and the belief in international cooperation, this is where the solidarity of countries’ policies on intercountry adoption can begin to take flight.

In my belief, the practice of intercountry adoption is not one to be completely discarded or denied, but one to be intensely scrutinized by international legal organizations and furthermore the governments of the countries involved, in order to maintain a highly standardized and regulated industry void of the same abusive qualities that littered it beforehand. The need to completely dismantle the private adoption agencies should not be necessary, if once again they are in good standing with the federal regulations that now exist. Accreditation is just one of many examples, that aid in determining which adoption service providers are adept in their field and which should be presumably put out of business. It is through this sort of international problem-solving, employing the art of collaboration and compliance, that this practice is now far more in tune with the rights of children, than it was a few decades back.

The Shift to Domestic Adoption

When the United States faced these new restrictive regulations and services which inhibited the less modulated flow of children from one country to the next, many prospective adoptive parents had to seek new channels. According to AFCARS (Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting Systems) data, the number of children waiting to be adopted decreased by 21 percent from 2001 to 2012.[31] This implies that children in public facilities across the United States, such as foster care, were being adopted at larger rates than previous years when intercountry adoption was also taking place in the United States. In domestic terms, the US has approximately 107,918 children available for adoption in the United States, currently.[32] This statistic is furthermore demonstrative of the sheer number of children in need of finding a family, a home, and a place to consider their own with people there to support them. There is no shortage of children, in the United States, who also are in need of finding adoptive parents.

In nations across the world, domestic adoption services and institutions (for the United States such as foster care), naturally had to brace for this shift. Due to international agents promoting the safeguard of private agencies and the industry of intercountry adoption, a shift to domestic adoptions then commenced. In terms of facilities and foster-care, domestic adoption services and major federal agents are incessantly aware of the reduction in intercountry adoptions. In this way, agencies promoting domestic adoption services, are more likely to enhance their own rules and increase the adoption rate. In part, this increase is due to the Hague’s Convention on Intercountry Adoption’s stipulation on “transnational adoptions being a final resort.”[33] A focal point to be obtained from this particular section is that due to intercountry adoptions global decline, domestic adoption then become the popular alternative, ultimately encouraging the betterment of these particular social systems.

Conclusion

From the inception of intercountry adoption to its less popular stages after the influence of the Hague’s Convention of 1993, it can be understood that its intentions have always been had with good intent. The issue at hand was usually the agencies’ facilitation of the adoptions. The margin for error increased with the lesser amount of regulation had upon the legal institution. Once more and more legal concerns presented themselves, citizens, international agents, and federal governments alike, had reasoning to interfere and discuss ways to safeguard this practice. Through the use of interrogative accreditation processes making certain of the company’s competency, and national policies enacted with impactful encouragement from international forces, the intercountry adoption process has become incredibly more difficult but also safer for the individuals whose lives are in the hands of the federal government or even agencies detached from public social services. Either way, it can be understood, that The Hague Convention of 1993 in regard to Intercountry Adoption was a strong catalyst for the creation of many national laws upholding adequate standards for intercountry adoption and ensuring the process is as safe for the child being adopted, that it could possibly be. The ethics behind intercountry adoption will constantly evolve for the better with the forces of liberal institutions such as The Hague consistently determining the efficiencies and deficiencies of the industry. With this constant evaluation from the international arena, comes a certain remodeling and fortification of the practice as well as the preparation for more internal adoptions to take place. This shift from international to domestic adoption is not particularly an unfavorable phenomenon, as it essentially promotes to betterment of social services within the country.

In the grand scheme of it all, a child’s rights should never be overlooked, the industry should not be capitalized off of, and the agencies at hand should incessantly be held accountable for their misdeeds. As The Hague preamble states, the convention was built on the foundation of “…recognizing that the child…should grow up in a family environment, in an atmosphere of happiness, love, and understanding.”[34] With the existence of certain international organizations and their constant oversight of adoption facilitation, comes more opportunity for this to occur.

[1] Mignot, J, “Why is Intercountry Adoption Declining Worldwide?”

[2] The Adoption History Project Website, “Adoption History in Brief”

[3] The Adoption History Project Website, “Adoption History in Brief”

[4] Adoption Council Website, “Your Guide to the 2017 Intercountry Adoption Stats”

[5] Adoption Council Website, “Your Guide to the 2017 Intercountry Adoption Stats”

[6] UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog, “The Dark Side of International Adoption.”

[7] Bainham, A. “International Adoption from Romania: Why the Moratorium Should Not be Ended.”

[8] UNICEF, Report on Child Trafficking in Africa

[9] Salt Lake Tribune, “Focus on Children Scam: No Jail Time in Adoption Fraud Case.”

[10] Cave, D. “In Tenn., Reminders of a Boy Returned to Russia.” The New York Times

[11] Ben, C. “Why Did International Adoption Suddenly End?” Priceonomics

[12] Ben, C. “Why Did International Adoption Suddenly End?: Priceonomics

[13] Bell, D. “What is Liberalism?”

[14] HCCH, “CONVENTION ON PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AND CO-OPERATION IN RESPECT OF INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION”

[15] HCCH, “CONVENTION ON PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AND CO-OPERATION IN RESPECT OF INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION”

[16] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Adoption Process.”

[17] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Uganda Intercountry Adoption Information”

[18] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Adoption Process.”

[19] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Adoption Process.”

[20] I-800 Official Document, “Petition to Classify Convention Adoptee as an Immediate Relative”

[21] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Universal Accreditation Act of 2012.”

[22] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Adoption Process.”

[23] Intercountry Adoption Accreditation and Maintenance Entity Policy and Procedure Manual

[24] National Authority for Child Protection and Adoption in Romania (2004) Child Care System Reform in Romania, Bucharest, Romania: UNICEF

[25] Lightfoot, E. “International Adoption from Romania: A Timeline (2 of 5)” Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare

[26] Lightfoot, E. “International Adoption from Romania: A Timeline (2 of 5)” Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare

[27] US Department of State Consular Affairs, “Universal Accreditation Act of 2012.”

[28] UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog, “Orphan Fever: The Dark Side of International Adoption.”

[29] Freundlich, “Adoption and Ethics,” 94.

[30] Smolin, D. M. “Abduction, sale and traffic in children in the context of intercountry adoption,” 3

[31] Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Trends in US Adoptions: 2008-2012” 19

[32] Adoption Network, “US Adoption Statistics”

[33] HCCH, “CONVENTION ON PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AND CO-OPERATION IN RESPECT OF INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION”

[34] HCCH, “CONVENTION ON PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AND CO-OPERATION IN RESPECT OF INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION”