Food Security in Latin America and the Caribbean: the Inter-American Development Bank and Ongoing Progress

By: Sophia Coleman

Introduction:

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are a broad and ambitious set of targets for the world to work toward, and eventually achieve, creating a world without poverty and inequality through sustainable action. In particular, the second goal to achieve Zero Hunger is both formidable in its task and crucial for the well-being and future of the global population. Specifically, it entails a world without hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in any of its forms [1]. While there is slight variation throughout academia about the working definitions of those terms, this paper will be using the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) definitions. Food security is defined as “the situation when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, nutritious food that meets their dietary needs for an active and healthy life” where food insecurity is any circumstance without complete access of nutritious food [2]. The components of food security include food availability, food access, food utilization, and food stability. Malnutrition also has multiple characteristics as it refers to undernourishment, micronutrient deficiencies and obesity, all if which need to be dealt with in turn as they are critical obstacles for healthy lifestyles [3].

The multidimensional essence of food security has made it a daunting task to confront as it requires coordination from various sectors and institutions. From trade to maintain food availability at the national level to climate change which poses immediate and long-term risks to food stability, the obstacles that need to be confronted are overwhelming, but this doesn’t make them any less imperative to be dealt with. Over the last few decades governments and organizations around the world have made concerted efforts to address hunger and all its contributing factors. Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) in particular has made notable progress at addressing malnutrition and food security. The most remarkable progress was made between 2000-2014 before a worldwide retrogression of progress took place from 2014-2020. This years-long backsliding led up to the COVID-19 pandemic which has dramatically affected all areas of life, food security among them.

The urgent and demanding need to tackle hunger and food insecurity, now more than ever, shows governments and international organizations alike that this is a pressing issue that can be successfully mitigated when looking at past experience. This paper aims to understand how the Inter-American Development Bank (IaDB), the leading source of development finance for the region, has or has not been prioritizing and acting on this Zero Hunger initiative, including current projects, partnerships, and plans for the future. To begin, there will be a brief overview on the progress and relapse of malnutrition and hunger across LAC, and what the IaDB has done to take on this crisis. I will also touch on how the current COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the region and how the IaDB has responded during the crisis with regard to hunger and food security. Finally, there will be an analysis on whether or not the Bank’s response was proportional to this problem or if the reaction was underwhelming, along with policy recommendations for the future.

Regional Progress and Pitfalls:

As previously mentioned, there was exceptional progress in the region combatting hunger and food insecurity in the early 2000s. From 2000-2014 the number of undernourished people throughout the region dropped by 20 million and Latin America and the Caribbean was the only region in the world to reduce the percentage of undernourished people [4]. LAC achieved the 1C target of the Millennium Development Goals, predecessor to the SDGs, to halve the proportion of people who suffer from hunger [5]. The region reduced the proportion of people suffering from hunger from 14.7% in 1992 to 5.5% in 2014 [6]. In contrast, worldwide reduction in the same time period went from 18.5% to 10.9%. Unfortunately, there are still many undernourished people in LAC, totaling 42.5 million as of 2018 and the numbers are expected to increase due to the current COVID-19 pandemic [7].

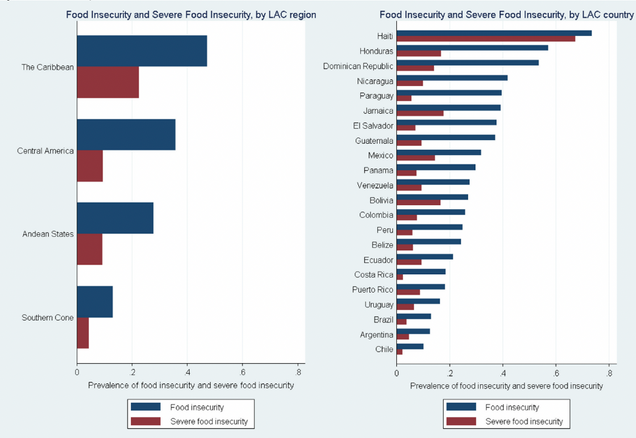

Despite this progress, a backsliding of sorts began in 2014 when, due to low economic growth, severe climatic events, unsustainable methods of food production and consumption, and demographic transitions, rates of undernourishment, obesity, and worsening food insecurity increased [8]. Figure 1 below shows a snapshot of the situation in 2014 of those across the region suffering from food insecurity by subregion and country.

In 2018, 42.5 million people were hungry, an increase of 4.5 million people from 2014 [9]. And according to the Food Insecurity Experience Scale, moderate or severe food insecurity in Latin America increased from 26.2% in 2016 to 31.1% in 2018, which meant a more than 32 million people increase to the 155 million already living with food insecurity [10]. Food environments, which encompass interactions between people and their physical, economic, and socio-cultural conditions and influence how they obtain and consume food, affect different population groups in various ways [11]. Social and economic inequality disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations like women, children and certain ethnic groups and their access to healthy diets. There are also gender disparities as 55 million adult men suffer from food insecurity compared to 69 million adult women [12]. Some other grim statistics include that an estimated 13.5% of children under five in LAC suffer from stunting and nearly 58% of the population is overweight, while 23% are obese [13]. The highest percentages of overweight and obese citizens occur in the Caribbean where poverty rates are also higher [14]. Malnutrition due to being overweight in the region is higher than most other parts of the world and continues to increase. According to the FAO, the index of adequacy of the food supply is 124%, which means that the average supply of calories for food consumption exceeds the average dietary energy requirement [15]. And over the last 15 years the caloric supply has increased by 15% to 3069 calories per person” [16]. These rising numbers are due to a number of factors, but it shows that this issue, if not constantly monitored and treated, can easily climb to dangerous heights, affecting millions of people in achieving healthy lives. This deterioration of the progress made only a few years before should already have been a red flag to organizations and governments across Latin America that this issue needs to be aggressively challenged in order to come anywhere close to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2.

The Inter-American Development Bank’s Role in Advancement:

This paper explores how specifically the Inter-American Development Bank has been prioritizing and acting on this goal, considering the severity of the problem. The Bank is the largest source of development financing for Latin America and the Caribbean with a mandate to accelerate the process of economic and social development of the regional members [17]. The IDB Group consists of IDB Invest, the Inter-American Development Bank, IDB Lab, and the Multilateral Investment Fund. The IaDB, with over $100 billion worth of assets, has the most spending power in the region and could undoubtedly aid the region’s efforts regarding SDG 2.

International and supra-national organizations have come up with a wide-ranging list of possible policy actions to address this crisis on an extended timeline. As has been referenced, hunger and food security are well-documented and serious issues for the region right now. Despite decades of impressive growth, the last few years have shown that there is still a need to address this thoroughly and proactively. It is imperative that states and international actors prioritize this cause, which is why this paper is examining the attention that has been paid on hunger by the IaDB pre-COVID to understand if there was a proportionate and adequate response before the onset of a global pandemic that transformed the world. With reference to IaDB actions, I pay attention to projects that could alleviate the pressures of food insecurity in the short-term, creating the most impact as quickly as possible.

To start, we must understand what the Bank was working on up through the start of 2020. There are 616 projects being implemented by the IaDB across sectors, totaling $56 billion in financing [18]. To address malnourishment and food security the Bank asserts that various multi-sectoral projects are currently enacted in areas like water and sanitation, social investment, agriculture and rural development, and health that deal with individual aspects of the problem at hand. But to what extent has this directly addressed food and the immediate needs of millions of people? A look at projects spanning from 2014 through early 2020, the period of increasing hunger before the onset of COVID, shows that few projects spoke directly to hunger and food security. The IaDB’s website sorts ongoing projects by sector, and I reviewed the sectors that I believe include the domains closest related to food and hunger needs in the short-term which included agriculture and development, education, social investment, and health. Of course, water and sanitation as well as trade and transportation are important in the supply of food for the long-term but there wouldn’t be swift results to alleviate hunger and therefor they were not included in this research. However, I did look at environment and natural disasters and modernization of the state sectors to see if there was any tangential relevance but there was neither a direct reference to food or hunger nor was there short-term planning. Projects were instead long-term or included vague mentions of health care systems.

Closer examination based on these parameters yielded few projects. The IaDB approved a $109,870,000 loan in 2014 for Honduras’ Social Protection System Support Program with the goals of promoting the formation of human capital through education services, health and nutrition, and supporting the consumption of beneficiary households [19]. This did not include a clear strategy on improving health and nutrition, but it mentioned nutrition in the proposal which was more over than many other project goals. In 2018 the IaDB launched SinDesperdicio, No Food Waste, on World Food Day to reduce food loss and waste and support the current partnership with the Global Food Network [20]. Specifically, IaDB supports GFN member food banks to train on safety, hygiene and contingency plans through grants to food banks. The Bank also encouraged public policies like adoption of labelling standards, norms and incentives for food donation, and would promote behavioral changes through awareness and training campaigns that try to minimize food waste. LAC loses or wastes more than 127 million tons of food a year, so this is attempting to meet a critical need in the region. The platform brings together companies from the food and technology sectors like Coca-Cola and IBM as well as partners like the UN FAO, GFN and World Resources Institute [21]. Again, it is worth mentioning that this investigation is only reviewing the projects that can most immediately create nutritious and sufficient food consumption, yet even with that caveat the results of the ongoing projects are disappointing.

Considering the resources the bank has at its disposal, and the need to progress on Sustainable Development Goal 2, it appears the response is not proportionate to the crisis. By separating the time periods from the backsliding era of 2014-2020 and then the effects of COVID from 2020 until the present I hoped to analyze how the Bank prioritized achieving this goal to end hunger. Following this research there is a serious need for the IaDB to step up. I had hoped to see more concrete policies to address this, or even projects that mentioned hunger or nutrition. Instead, the results are uninspiring. If we broaden the scope to include social security programs with less of a focus on food and hunger or agricultural production, there are indeed existing projects, however these objectives focus on the long-term rather than imminent needs. Even when looking at projects within the IaDB’s health sector they only outline plans to build digital infrastructure for health care systems and do not touch on hunger.

COVID-19 Impacts on Hunger and IaDB Responses:

Since the COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the world in 2020, it has touched upon all sectors of life. The Inter-American Development Bank took action to combat these effects across sectors in LAC. For example, to continue financing companies in the region the Bank supplied several bond issues in 2020. In March of last year 5-year Sustainable Development bonds worth $2 billion were issued and in April 3-year Sustainable Development bonds worth $4.25 billion were issued as well [22]. Furthermore, to address COVID directly the Bank announced up to $12 billion in various programs across the region for countries to use for disease monitoring, testing and public health services [23]. And of the $21.6 billion in financing approved in 2020, $7.9 billion went directly as support to country responses rather than to the private sector or entrepreneurs [24]. So far in 2021 $132.3 million has been approved for country use. These statistics show that the Bank has considerable accessible resources and were willing to take substantial measures to support the region from the health sector, to the economy and social services.

Before COVID food insecurity was on the rise at 25% of the population and hunger, malnourishment, and food insecurity are likely to worsen. At the end of May last year, the UN World Food Program contended that 14 million people in LAC could experience food insecurity due to COVID [25]. School closures from lockdown restrictions means children that rely on healthy school-provided meals could suffer. Unemployment and lower incomes could affect household consumption and the availability of cheap fast-food options could continue to increase overweight and obesity levels. Responses to hunger, malnourishment and food insecurity need to take action that yield immediate results to increase healthy food consumption across Latin America and the Caribbean.

When reviewing policy and project proposals that the IaDB has published to outline their responses to the pandemic, very little is mentioned about hunger or food security. According to the Social Policy Responses to the Effects of COVID-19 paper published by the IaDB which looks at social policies in education, labor, gender, and health, there is no explicit mention of hunger or food security [26]. While the health section looks at unequal access to healthcare and how the pandemic affects mental health there is a noticeable lack of a discussion on hunger. The report on Inequality and Social Discontent: How to address them through public policy focuses on some of the hardest hit countries concerning hunger and malnourishment in Central America, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Mexico, and Panama [27]. Though there are no food security related policies or programs being created in a partnership with IaDB, national programs are using funds granted or loans given to support their own programs to help vulnerable citizens access nutritious food. For instance, Costa Rica has a food delivery program for most vulnerable families and El Salvador had one million food parcels dispatched, and food voucher programs in Guatemala and Panama all received financial support through the IaDB to fight hunger within their borders [28].

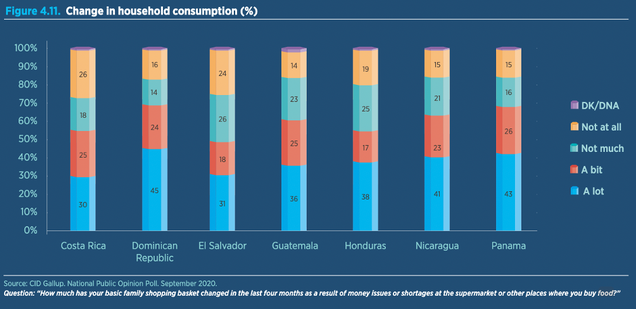

The report also confirms what is widely accepted that poverty and food insecurity are correlated and countries with the highest poverty rates – Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua – also have the most profound food insecurity due to the effects of COVID [29]. Additionally, unemployment and lower earnings levels caused by the pandemic have negatively affected many citizens’ basic market basket and consumption levels. Based on survey findings in the above report, over 50% of all Costa Rican, Dominican, Salvadoran, Guatemalan, Honduran, Nicaraguan and Panamanian citizens feel that their basic market basket has changed as a result of their “limited means or supermarket shortages” [30]. Specific rates of responses for those countries can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Other projects that have been implemented as a response to COVID to address food security include $250,000 of technical cooperation approved in June 2020 to strengthen health, education, and food services through NGOs in Venezuela [31]. Though less direct a response to food security, the Bank approved $60 million in grant financing to support vulnerable people in Haiti as a recovery measure to COVID [32]. Again, when reviewing projects by sector that could relate back to hunger, education included nothing about changing food habits and behavior, and health sector projects were focused on COVID and vaccinations with nothing proposed to combat food insecurity.

When reviewing the current projects and programs it appears that there is an underwhelming response to the hunger and food security problems across Latin America and the Caribbean. This paper examined the extent to which the IaDB was proactively working toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2, specifically how the population’s needs were being met in the short-term. Considering the recent regression of progress and the ever-present need to reduce hunger, improve nourishment and food security, the Bank’s efforts up until 2020 were underwhelming in response to the crisis. While the COVID responses covered an array of sectors and difficulties posed by the pandemic, hunger and nutrition were not treated as priority concerns despite the fact that hunger and food insecurity were on the rise and presented struggles for everyday life.

Policy Analysis and Recommendations:

This paper studied immediate consumption needs, and future policies need to meet those short-term demands as well as long-term plans. Overall, the needs to slow down and reverse the increase in overweight and obesity have not been met. There were no IaDB programs in the education sector targeting nutrition and healthy eating habits to reduce overweight and obesity. Therefor this paper strongly recommends tackling obesity at all age levels through behavioral changes in the population as this subsection of malnutrition continues to worsen. Education on healthy eating habits starting at an early age in primary school could restructure food behaviors and prevent overweight and obesity as the population ages. Campaigns targeted at older sections of the population could also help reduce these levels and adverse health risks from obesity within a few years. Specifically moving away from fast food to more nutritious options in the next few years could make significant headway in the near future and change habits for the long-term.

Existing health apparatus across the region need to include nutrition programs and explicitly mention eating habits to improve overall health care treatments. Incorporating initiatives that precisely deal with food accessibility in systems that methodically reach the population in their approaches could ensure that citizens don’t fall through the cracks with specific campaigns or actions targeting different vulnerable groups, such as women, particularly mothers, the poor, and other minorities. Another way to go about this would be if existing programs in the health, income and social sectors carried out by the Bank were to incorporate food and hunger into the mandates, or to expand on those that already exist. For states that already implement conditional cash transfer or food voucher programs, these strategies should have increased funding from the Bank to reach more of the underprivileged population and boost the spread of aid to ensure people are eating adequate amounts of healthy food for their lifestyles. These solutions have been proven effective, especially the Bolsa Familia program in Brazil, and if the Inter-American Development Bank were to use its considerable resources to help states structure their own programs, or fund those that are already helping people in the time of COVID, this could guarantee a source of healthy food that millions have been lacking. Or partnering with local food banks across the region could help grow resources within existing organizations that reach people at more remote or rural areas that need help but have often been overlooked.

In a more prolonged timeline, there are numerous policy options. Increasing income has been shown to increase consumption and provide more resources to buy healthier food that tends to be more expensive. Lowering poverty rates of the most vulnerable would also reduce hunger and malnourishment in the long-term. On a more macro level, improving agricultural infrastructure and delivery chains, creating interventions to reduce food loss, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices to increase production and consumption are all beneficial policies that would increase food security. Increasing consumption, availability, and accessibility of healthy options are crucial to end hunger and ensure food security in the long-term. Fortifying existing systems or creating new ones with clear plans to go from producer to consumer in the most efficient way possible is imperative in realizing Sustainable Development Goal 2 and improving the lives of millions across Latin America and the Caribbean. Initiating specific guidelines or including hunger in the hundreds of ongoing IaDB projects could make substantive change across the region. With the effects of COVID-19 not yet fully documented this problem is even more critical if we are to help millions of people find healthy meals to sustain themselves. The Bank has abundant resources ready to help the Americas, and with more detailed projects aimed at food security, this crisis could be considerably lessened that would benefit generations to come.

[1]. 2019 Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition in Latin America and the Caribbean. FAO, PAHO, WFP and UNICEF, 2020.

[2]. Smith, Michael D, Kassa, Woubet, & Winters, Paul. “Assessing food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean using FAO’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale.” Food Policy, 71, 48– 61. 2017.

[3]. Ibid.

[4]. FAO, 2020.

[5]. Mahlknecht, Jürgen, et al. “Water-Energy-Food Security: A Nexus Perspective of the Current Situation in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Energy, vol. 194, 2020, p. 116824, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.116824.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. FAO, 2020

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. Ibid.

[13]. Winters, P., Falconi, C., Martel, P., Miranda, J.A., Paiva, M., 2015. Background Paper for the Food Security Sector Framework Document. Prepared for the InterAmerican Development Bank.

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. Mahlknecht et al, 2020

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Tsvirko, Svetlana. “Comparative Analysis of the International Development Banks’ Activities During COVID-19 and Beyond.” Comprehensible Science, 2021, pp. 175–85, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66093-2_17.

[18]. “Project Details | IADB.” Inter-American Development Bank, 2021, www.iadb.org/en/projects-search?country=§or=IS&status=Implementation&query=&page=12.

[19]. Ibid.

[20]. “GFN and the Inter-American Development Bank Join Forces to Combat Food Waste and Food Insecurity.” The Global FoodBanking Network, 19 June 2020.

[21]. Ibid.

[22]. Tsvirko, 2020.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. “IDB-Financed-Projects-in-Response-to-COVID-19.” Tableau Software, 2021.

[25]. Global FoodBanking Network, 2020.

[26]. Arboleda, Oscar, et al. “Social Policy Responses to the Effects of COVID-19.” IADB, March 2020.

[27]. Inequality and Social Discontent: How to address them through public policy, Public Report on Central America, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Mexico and Panama. Inter-American Development Bank, 2020.

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. Ibid.

[30]. Ibid.

[31]. Project Details, 2021.

[32]. Ibid.