Seoul, South Korea. Photo by zero take via Unsplash.

By Frank Jiaqi Wang

Abstract

Due to warfare, persecution, poverty, and other survival-related factors, refugee crises continue to exist as an urgent and globalized issue waiting to be addressed. On the Korean Peninsula, the overall well-being of North Korean citizens is threatened by the aggressive actions and misguided policies of a totalitarian and repressive regime. For the sake of their freedom and livelihood but in the face of punishment and death, some brave souls choose to cross the border and start a new chapter of life in a democratic society while holding the title of “defector”. However, along with the fascinating possibilities, this new life brings serious obstacles. North Korean defectors are not only confronted with issues associated with unemployment and family separation but are also treated differently and even harshly by their South Korean neighbors for their cultural and socio-political background. As a result, some have given up the process of resettling and adapting. They instead have chosen to return to their home country where unimaginable dangers await them.

By exploring the emotional stories and hardships of North Korean defectors living in South Korea, this paper seeks to explain the nature of the refugee crisis and shows how cultural conflicts can result in tensions between newcomers and hosts, which further exacerbates the mistreatment and re-displacement of refugees. An introduction to the global refugee issue and the term “defector” will first be provided, followed by a regional analysis involving the historical background and contemporary social development of the Korean Peninsula. The analysis will delve into the cultural and social differences and similarities of the two Koreas. Then, obstacles related to North Korean defectors’ cultural adaptation in the neighboring South, namely alienation and discrimination by South Koreans and their struggle to resolve a series of identity crises, will be introduced and analyzed through cultural and socio-political lenses. Lastly, insights and lessons from the unique stories and experiences of North Korean defectors will be drawn to reflect the challenging and disturbing nature of the global refugee crisis, both in the current and future of the world, and further enhance the collective understanding of specific procedures involved in ensuring a better life for refugees around the world.

An Overview of the Global Refugee Crisis

People in various regions of the world are suffering due to severe threats to their survival, which mercilessly force them to flee their homeland and assume the role of refugees. According to statistics published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there were 108.4 million forcibly displaced people worldwide at the end of 2022, and 35.3 million of them were refugees.[1] Women and children are two of the most affected groups. The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that 43.3 million children were displaced due to various crises at the end of 2022.[2] Moreover, women and girls constitute 50 percent of any refugee groups and are threatened not only by man-made disasters but also by sexual violence. The numbers continue to grow each day.[3] While the whole world faces this sad reality, the lack of international consensus to house refugees generates an additional burden for developing countries, which host the majority of the world’s refugees as mandated by the UNHCR and, at the same time, lack sufficient resources to ensure stability and overall well-being of the population.[4]

Despite the urgency of the situation, refugee status cannot be granted to all. There are critical differences among refugees, internally displaced people (IDPs), migrants, and asylum seekers. Refugees are defined as “people who have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country.” They are “unable or unwilling” to return to their country due to fear of further persecution or harm, whereas IDPs remain in their own country and are not eligible for special protection or aid during their stay.[5] Migrants are characterized based on the voluntary nature of their decision to leave their home country or region and thus do not enjoy special protection or aid.[6] Lastly, while asylum seekers are similar to refugees, as both seek to escape persecution and human rights violations committed by their home country or government, refugee status will only be offered after they have completed the application and are approved by their host country.[7] From a legal perspective, refugees have international legal protection and rights granted by the Geneva Convention.[8] While awaiting to be addressed, the ongoing global refugee crisis continues to be directly exacerbated by the existence of political, societal, and economic issues, including interstate and civil warfare, poverty, and persecution based on “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”[9]

The Current Situation on the Korean Peninsula

On the Korean Peninsula, the totalitarian governance of North Korea has caused continuous economic downturns and tightened harsh policy measures that directly caused many to undertake a long and risky journey across the main regions of Asia, which would eventually lead them to the neighboring and democratic South. Recent numbers show a total of sixty-seven North Koreans were able to defect to the South in 2022, marking one of the lowest annual numbers.[10] This number demonstrates not only the restrictive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic imposed on refugee movements, as published numbers in previous years were in the thousands, but also the defectors’ unwavering commitment to freedom and survival amidst difficult times. Although the proper categorization of North Korean defectors remains disputed in the fields of academia and politics, they have been considered either refugees or migrants throughout different periods of history. This is due to South Korea’s ambivalent policy, a significant factor in aligning defectors with refugees and understanding the group’s overall identity as their hardships in a new land.[11] As shown by the journeys of North Korean defectors, it is clear that cultural conflicts can cause socio-political tensions, misperceptions, and identity crises, directly exacerbating the mistreatment and re-displacement of refugees and further preventing effective social integration of the group.

The Division of Korea: The Effects of History on Contemporary Rhetoric

History not only explains the dramatic differences between the two Koreas but also orchestrates a total clash of sociopolitical values and national identities that negatively impacted North Korean defectors’ current image and integration into the South. Prior to the arrival of Japanese colonial occupation in the early 20th century, which had lasted for more than three decades and planted the seed of division, Korea was able to maintain a cohesive culture and a unified political community for centuries.[12]

During the colonial occupation of Korea, Japanese officials favored well-educated and wealthy Korean Christians and landlords as collaborators in implementing and enforcing the colonial agenda while opposing and suppressing nationalist and communist activities.[13] Domestic advocates for Korean independence, including nationalists and socialists who battled with anti-nationalist collaborators, were labeled as “communists” by colonial officials as a retaliatory technique.[14] Following Japan’s surrender, former collaborators funded conservative political parties to continue battling with communists and leftists alike further justifying anti-communist ideals as a form of passionate “patriotism” and firm opposition to the enlarging Soviet sphere of influence in Northern regions and neglecting sacrifices to national unity in the face of personal and political interests.[15]

Divisive post-colonial domestic politics, in combination with great power geopolitics, eventually produced the formation of two governments in Korea with the creation of the 38th parallel, a Soviet-led communist regime in the North and a US-backed dictatorship in the South, that fueled the outbreak of the Korean War and long-lasting tensions between the two sides, which persist to this day.[16] Influenced by the hatred and bloodshed of the past, both sides are powerfully determined to reunify Korea as a single state under one preferred ideology, with military force being one of the necessary measures for achieving this prioritized goal.

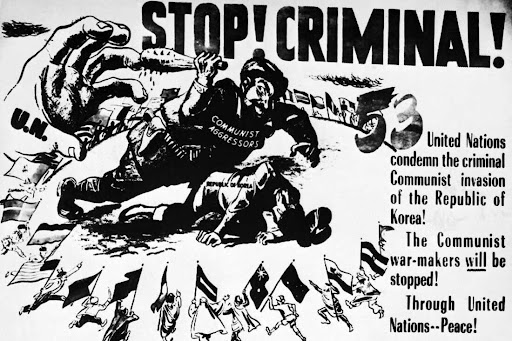

Politically, the regime in North Korea is viewed as an enemy of South Korea in part due to its affiliation with communism.[17] However, such a hostile image expanded out of the field of politics and into the minds of South Koreans across multiple generations. The U.N. propaganda poster during the Korean War era, which highlighted the criminal aggression of communist North Korea, was misinterpreted by citizens of the South as an accurate portrayal of North Koreans (see Figure 1).[18] The demonization of North Koreans became a popular trend in the South. According to published interviews with South Korean seniors, North Koreans were portrayed in South Korean schools as beasts with horns on their heads at the height of the Cold War.[19] The false imagery of North Koreans is difficult to be corrected in today’s society, as genuine reports of daily activities in North Korea and related websites are being heavily censored due to South Korea’s Cold War national security law.[20] Moreover, the use of anti-North slurs continues in the contemporary South. Ppalgaengi, translated as “commies,” was frequently used during the Korean War era to exclude North Koreans from becoming a part of a unified national community and still serves as a weapon to verbally attack defectors and supporters of peaceful reunification policies under the current system.[21] As a result, the long-lasting effects of history remain difficult to eliminate and still pose concerning challenges to arrivers from the North.

The Journey of North Korean Defectors: A Continuous Struggle

For North Korean defectors, the journey of leaving their home country and settling in a new and unknown land is both a physical and mental challenge. Despite the close geographical proximity between the two Koreas, the five-stage escape route taken by the defectors requires facing a significant amount of risks (see Figure 2).[22] China, which has been cooperating with Pyongyang to deport defectors and limit assistance programs, nevertheless remains a necessary destination on the group’s route to freedom.[23] Moreover, if the defectors were to cross China’s heavily militarized border successfully without being caught by authorities and sent to detention camps, they must embark on a multi-day journey to countries in Southeast Asia, from Laos or Myanmar to Thailand, which would enable their arrival in South Korea.[24] Unfortunately for the defectors, the struggle does not end there.

New defectors from the North are required to undertake mandatory screening, lengthy investigations, and detention by South Korea’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) to ensure the genuineness of their arrival before allowing them to be trained and educated about their new life.[25] However, such a process is not completed without unnecessary suspicion and controversies. The NIS and its programs have been criticized for politicizing North Korean defectors through “concocting fake spy cases to arrest and discredit dissidents,” which is influenced by high-level opposition to “pro-North Korean leftist” officials and policies.[26] Moreover, the group’s overall well-being is threatened by mistreatment and human rights abuse while being monitored by the NIS. A defector who was targeted and arrested reported that she was placed under duress after being beaten by interrogators and held in solitary confinement for more than a hundred days. Another defector chose suicide in response to forced confession to being a spy.[27] These particular incidents are not only damaging to the reputation of the host country but also to the defectors’ early stages of integration.

For defectors who can enter a new society, they have to confront the reality of being labeled as the “cultural other.” The geopolitical division of Korea carries cultural significance. Not only have intercultural communication and interaction between citizens and governments of the two countries been restricted to the maximum degree since the end of the Korean War, but the common way of life and the cohesiveness of the Korean culture overall have been devalued.[28] Despite the existence of ethnic and linguistic bonds, a closed border and heavy censorship signify the fact that North Koreans and South Koreans have limited knowledge about each other’s changing cultural values, which in turn, fosters a unique but troublesome environment for the integration and adaptation of North Korean defectors, as they could be perceived as both ethnic insiders and cultural outsiders by South Koreans. [29]

Due to societal forces of the South, ranging from mass media to the hateful and biased conduct of certain individuals, the “other” aspect of North Korean defectors’ identity is being continuously portrayed to the audience of the host country.[30] In South Korea, TV shows and interviews involving North Korean defectors often demonstrate the negative aspects of the group’s life in their home country, ranging from political oppression to other hardships, which not only can trigger an emotional nightmare in the minds of defectors but also contributes to the marginalization of the group by highlighting their differences in personal experience and lifestyle over similarities shared with their counterparts from the South. Moreover, prejudice and discrimination against defectors is a common phenomenon in South Korea. Similar to the tactics used by others in various regions of the world to alienate refugees, some South Koreans often blame the defectors for wasting taxpayers’ money by enjoying social welfare benefits provided by the host government while falsely accusing the group of being communists and spies.[31] At the same time, low-income South Koreans believe that their government treats them unfairly by offering defectors resettlement payments.[32]

Discrimination and alienation of North Korean defectors are further accompanied by instances of cultural shock. Transitioning from a closed totalitarian system to a modernized capitalist state means that the defectors have to adopt the “cosmopolitan habitus,” which focuses on gaining global knowledge and experience (i.e., living overseas and learning a foreign language) to acquire the necessary skills for engaging with the global community.[33] Due to the separation of culture that results in differences in dress code, speech, and manner, it is difficult for defectors to effectively integrate into the mainstream society of the South, which generates additional obstacles for the group to avoid being treated as the “other.” Statistics from a survey show that 45.6% of South Koreans reacted negatively towards North Korean defectors due to their distinct physical embodiment (i.e dress code, manner, cultural characteristics) and accent, and such a discriminatory reaction can target the group in multiple settings, including school and workplace.[34] In response, while 58.4% of young defectors feel reluctant to admit their North Korean origins, others choose the path of cultural assimilation by perfecting their South Korean accent and adopting a luxurious style of living, which can be costly and is hardly effective in preventing negative treatment of the group as a whole.[35] Moreover, securing employment opportunities is difficult for defectors. Due to the strict system of job and task assignment the North Korean regime imposes on its citizens, most defectors are unfamiliar with the concept of free will and personal decision-making power that a democratic society can offer.[36]

As a result of these negative experiences, the mentality of some defectors began to experience an unexpected shift. Due to unacceptable cultural conflicts and negative treatment, not all defectors are able to settle in South Korea. On New Year’s Day 2023, a young defector chose to cross the demilitarized zone and return to North Korea after spending more than a year in the South.[37] To explain the potential causes of the re-displacement of the defector in addition to the possibility of espionage and discrimination by members of the host country, some experts state how he could be a North Korean elite, such as an athlete, who is not satisfied with his less privileged life in South Korea, while others point to loneliness and trauma caused by economic hardships and the absence of emotional attachment exacerbated by the pandemic.[38] Such an instance, though uncommon, represents a serious consequence of defectors’ mental obstacles associated with integration and adaptation that motivated them to retrieve an old life in the face of danger and punishment.

Identity Formation Among Defectors: Challenges and Coping Strategies

Maintaining an optimal and authentic development of identity is a crucial task for North Korean defectors who seek to overcome popular misperceptions and further adjust, interact, and fit in as newcomers. In terms of self-identification, the majority of defectors avoid identifying themselves as North Koreans at all. The annual survey of North Korean defectors conducted by the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University shows that approximately 80 percent of respondents identify themselves as South Koreans rather than North Koreans.[39] At the same time, some defectors choose to distance themselves from other defectors and omit contact or interactions with defector networks, further reinforcing the South Korean identity.[40] However, living with media portrayals of North Koreans as dramatically different from South Koreans while interacting with native South Koreans on a daily basis presents significant challenges for some North Koreans to avoid the defector label.[41] The result is not only feelings of isolation and discrimination but also a clash between powerful self-identity and firm rejection by the natives.

Although the South Korean government has proposed measures to streamline identity formation among defectors, specifically for integration in the workplace, by connecting the group with job offers and providing them with various assistance programs, 25% of defectors are both unable and unwilling to complete the necessary training and tasks, and 19.9% remain unemployed. In addition to differences in communication style, North Korean defectors generally have limited resources, such as personal connections and family ties, to build strong social networks that support their acceptance to a new setting. Moreover, although Christianity and churches are regarded by many defectors as a means to become integrated members of the South, confusion arises when some newcomers are confronted with ideological diversity that is different from the absolutist nature of ideology back home.

As an essential coping strategy to tackle uncertainties, some defectors and natives bonded together and established community service groups. For example, Woorion, an NGO founded by both North Korean defectors and South Korean natives, provides essential assistance for defectors at the grassroots level in areas ranging from settlement support and mentor counseling to education and human rights research. Daehyeon Park, the CEO of Woorion and a defector, said in an interview that he wishes to explore the community’s voice and further build a community overseas by providing networks and connections for North Koreans living in the South. The existence of these groups not only helps defectors overcome issues associated with the transition to a brand new life but also enhances group identity among the newcomers and further harmonizes the relationship between North Korean defectors and South Korean natives for the benefit of creating a unified and cooperative cultural partnership in the society at large.

Drawing Lessons and Building A Better Future for Refugees

The current refugee system is deeply flawed because too many countries in the world today still treat hosting refugees as a burden rather than a responsibility. Alleviating the refugee crisis and building a better and more welcoming environment for refugees around the world requires additional input from both the governments of host countries and the international community. In response to sexual violence, human trafficking, murders, and other forms of crimes harming refugees across different regions and communities, additional security and inspection mechanisms need to be developed at both regional and international levels to safeguard refugees from unwanted actors or influence. Moreover, national governments and domestic agencies accepting refugees should enact necessary laws or regulations to increase transparency and promote humane hosting/living conditions for newcomers in detention and processing facilities, as there have been instances involving mistreatment of refugees reported in multiple host countries worldwide, not just in South Korea. Hosting governments should also start or continue to allocate sufficient resources to provide social benefits and welfare programs for refugees to settle and work in new countries.

At the same time, the important role of civil society played in refugee resettlement must not be ignored. The case of North Korean defectors reflects how critical it is for the hosts to welcome the newcomers and understand their hardships to avoid conflicts and discrimination. The creation of Woorion also illustrates that members of the host society can serve as cultural ambassadors and help refugees integrate and adapt to a new setting. As a result of misjudgment and misinformation, citizens of many countries today still seek to alienate refugee groups out of fear. Therefore, to undermine misperceptions, collective community service programs should be formed in hosting countries to raise awareness of the ongoing refugee crisis and educate members of the host countries about the stories of refugees.

[1] UNHCR. “Refugee Data Finder.” United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees, October 24, 2023. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

[2] The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). “Child Displacement.” UNICEF Data, June 2022, https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-migration-and-displacement/displacement/.

[3] UNHCR. “Women”. United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/women.

[4] Edmond, Charlotte. “84% Of Refugees Live in Developing Countries.” World Economic Forum, 20 June 2022, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/06/eighty-four-percent-of-refugees-live-in-developing-countries.

[5] UNHCR. “What is a refugee?” United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/what-is-a-refugee.html.

[6] Doctors without Borders. “Global Migration and Refugee Crisis”. Doctors without Borders, 15 June 2022, https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/focus/migration-and-refugee-crisis#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20global%20refugee,or%20other%20life%2Dthreatening%20circumstances.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Save the Children. “What Is a Refugee? Important Facts and Figures about Refugees”. Save the Children, https://www.savethechildren.org/us/what-we-do/emergency-response/refugee-children-crisis/what-is-refugee#:~:text=People%20become%20refugees%20for%20a,Ethnic%20or%20political%20violence.

[10] Bremer, Ifang. “Only 67 North Korean Defectors Reach South in 2022, Second Fewest Ever.” NK News, 10 Jan. 2023, www.nknews.org/2023/01/only-67-north-korean-defectors-reach-south-in-2022-second-fewest-ever/.

[11] Kim, Sung Kyung. “”Defector,” “Refugee,” Or “Migrant”? North Korean Settlers in South Korea’s Changing Social Discourse 1.” North Korean Review 8, no. 2 (2012): 94-110, doi:0002006743; 1O.3172/NKR.8.2.94.

[12] Ha, Shang E. and Jang, Seung-Jin. “National identity in a divided nation: South Koreans’ attitudes toward North Korean defectors and the reunification of two Koreas”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Volume 55 (2016): 109-119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.10.003.

[13] Kim, DC. “The social grounds of anticommunism in South Korea-crisis of the ruling class and anticommunist reaction”. Asian j. Ger. Eur. stud. 2, 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40856-017-0018-1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ha and Jang, “National identity in a divided nation”.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Hu, Elise. “Why Do Some South Koreans Believe a Myth That North Koreans Have Horns?” National Public Radio (NPR), 4 April 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/04/04/521742040/why-do-some-south-koreans-believe-a-myth-that-north-koreans-have-horns.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Bumsoo Kim; “Are North Korean Compatriots ‘Korean’? The Trifurcation of Ethnic Nationalism in South Korea during the Syngman Rhee Era (1948–60).” Journal of Korean Studies 24, no. 1 (2019), 149–171. doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.1215/21581665-7258094.

[22] Harris, Bryan, and Michael Peel. “Escape Route from North Korea Grows Ever More Perilous”. Financial Times, 23 June 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/8e0ba354-5229-11e7-bfb8-997009366969.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Poorman, Emma. “North Korean Defectors in South Korea and Asylum Seekers in the United States: A Comparison”, Northwestern Journal of Human Rights 17. no.1 (2019): 1-3-104, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol17/iss1/4.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid, 104.

[28] Hyo Chun, Kyung, “North Korean Defectors as Cultural Others in South Korea: Perception and Construction of Cultural Differences,” Journal of Peacebuilding 10, no. 1 (2022): 187, 192, 194, doi: 10.18588/202203.00a227.

[29] Ibid, 192.

[30] Ibid, 194.

[31] Lee, Ahlam, “North Korean Defectors in a New and Competitive Society: Issues and Challenges in Resettlement, Adjustment, and the Learning Process.” (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015), 60, 64.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Jung, K., Dalton, B. & Willis, J., “The Onward Migration of North Korean Refugees to Australia: In Search of Cosmopolitan Habitus”. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: an Interdisciplinary Journal. 9, no. 3 (2017): 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v9i3.5506.

[34] Ibid, 7.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Lee, 60.

[37] Lee, Michelle Ye Hee, and Min Joo Kim, “After a North Korean Defector Returned Home, a Struggle for Clues to His Life in the South.” The Washington Post, January 15, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/15/north-korea-defector-identity/.

[38] Ibid.; Collman, Ashley. “Former North Korean Defector Who Made Rare Cross-Border Return Home Could Have Been a Spy or Simply Unhappy with Life in the South, Experts Say”. Insider, January 4, 2022, https://www.insider.com/experts-explain-why-north-korean-defector-returned-across-border-2022-1.

[39] Shin, HaeRan; Chun, Kyung Hyo; Lee, Hyunuk; Kim, Heuijeong; Kim, Seok-hyang; Shin, HaeRan. “North Korean Defectors in Diaspora: Identities, Mobilities, and Resettlements” (Lexington Books, 2022), chap. 7, Kindle.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.