Initiation, Immersion, and Invitation: Three Environmental Compositions for Opera

Megan Grumbling, Poet and Librettist, University of New England

Banner photo by Kenny Filiaert on Unsplash

Since I was a small child, I’ve been inspirited by the myriad intricacies of wings, tentacles, tendrils, roots, and all the other natural wonders all around us. As a poet, I’ve sought to cycle energy back into these systems, so to limn, praise, and nurture the natural world that still so inspirits me. And as a librettist, writing words to be interwoven with music, I’ve found especially rich opportunities to engage with both the beauties and the crisis of our environment.

When I first began collaborating with composers, about 15 years ago—first with the late composer Denis Nye, of Portland, Maine, and later with the Copenhagen-based Marianna Filippi—I thrilled to the possibilities of pairing my words with music, particularly in environmentally-themed works. Since then, my operatic projects have included an ancient myth vaulted into the age of climate crisis, an homage to an octopus, and a choir to be sung in the voice of a glacier. In an environmental moment in which we too often feel afraid, despairing, and isolated, these collaborations have shown me that works of words married with music can allow us a more imaginative, intimate, and emotionally expansive engagement with complex ideas about nature and environmental crisis. As a collaborative and interdisciplinary mode, environmental opera can embody the ecological intricacies and symbioses that it often praises. And as performance, opera about the natural world can offer both artists and audiences an opportunity to sit with our environmental joys and fears in community and in communion.

In this essay, I discuss three environmentally themed compositions on which I’ve collaborated, each with a different subject, style, and rhetorical, literary, and musical approach. I describe these modes as Initiation, Immersion, and Invitation.

Initiation is the mode most central to the opera Persephone in the Late Anthropocene, which inducts audience-members as participants into and through a ritual story of climate crisis. Inspired by the Mysteries of ancient Greece, Initiation as a musical and narrative mode can help us to work through environmental difficulty or grief by reconnecting us to our core resilience, values, and love.

The mode of Immersion fuels the short composition Through the Eyes of an Octopus by allowing audiences to bathe and bask in the sensory experience of one remarkable nonhuman being. The intimacy of such visceral identification with another creature could prove to be a powerful and pleasurable incitement to cross-species empathy.

Finally, Invitation is the mode that most grounds Snow, Millennia, and Blue, a short composition-in-progress that is a paean to glaciers. The mode of Invitation welcomes audiences into opportunities to think, feel, grieve, imagine, and be changed—all crucial acts for practice and praxis in our environmental moment.

Collectively, these three compositions present a range of ways that words and music together might re-engage our relationships with the natural world, heighten our stakes and agency in responding to environmental crisis, and renew our capacity to feel joy, empathy, and connection with our fellow beings and forms.

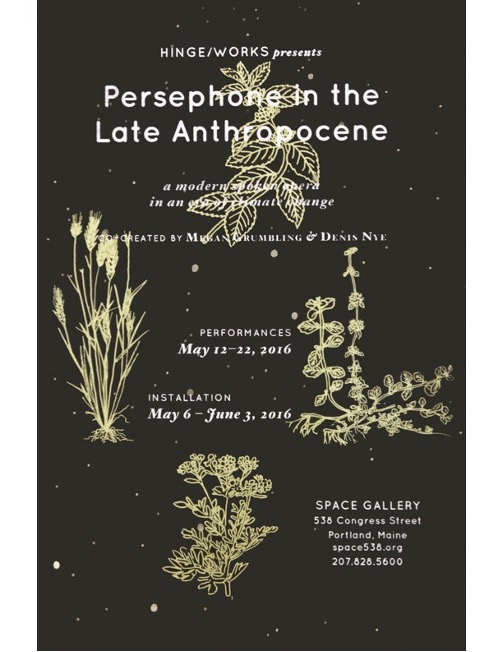

Initiation: Persephone in the Late Anthropocene. (Co-created with composer Denis Nye; produced in Portland, Maine, 2016). Listen to a recording of the opera’s instrumental score. For references to the author’s text: See Grumbling (2020).

When our seasons turn strange and erratic, what happens to our stories? To our heroes? What happens to Persephone, and to the deal she once struck between our world and the Underworld—the very deal that, in one story, gave us the seasons?

This is the question that spurred the birth of Persephone in the Late Anthropocene, an experimental opera that I co-created as librettist with the late composer Denis Nye. I’d met Nye some ten years before in the scrappy arts scene of Portland. He often spoke of his music in the idiom of landscapes, and he had a particular devotion to presenting both the beauty and the brokenness of our world. Nye and I collaborated as the production company Hinge/Works on several compositions before we began Persephone, our first explicitly environmental opera and our final work together before his death in 2016.

We conceived Persephone as a sequel to the classical myth, and we intended its near-future ecological and psychological dystopia to be recognizably unsettling to our audiences, with its floods and fires, guilt and grief. In the original myth, when Persephone is abducted to the Underworld by Hades, her mother, Demeter, halts all the fruiting of the earth as she searches for her daughter. Eventually, a deal is struck: Persephone will hereafter spend three months of each year underground (one for every pomegranate seed she has swallowed in the Underworld). The myth explains the phenomena of the seasons and of ecological limits.

In our opera—essentially a modern sequel to the classical story—we find the goddess coming and going erratically, and unseasonably, between our world and the Underworld. She drinks too much, eats too many exotic fruits, takes a human lover, and engages in other unsettling and manic decadences. Her unpredictable behaviors are a metaphor for the extreme disruptions of climate change, and her justifications for them mirror humans’ own naïve, dangerous, and environmentally oblivious actions.

As it did in ancient times, then, the Persephone story serves in our opera both as a lens for the seasons and as a proxy for our own human impulses and limits. And as in ancient times, the Persephone story of our opera also constitutes a certain kind of mystery: For generations, ancient Greeks enacted the Persephone myth as part of The Eleusinian Mysteries. These initiates, or mystai, took part in the Mysteries by going into a literal and figurative darkness, seeing a light, and coming back out transformed and renewed—having found both literal and figurative illumination.

These Mysteries became the foundation of our opera, which was, in this classical sense, a Mystery as well. Our aim was to make mystai, or initiates, of the audience themselves—to take them on a journey into the darkness of what we know and fear of our environmental crisis, then lead them back out the other side into the light, to find themselves having changed during our journey together.

The libretto of Persephone encompasses a range of styles, moods, and attitudes toward the natural world and environmental crisis. As with ancient Greek gods, our characters represent projections of human qualities, whether weaknesses or strengths; we intended for the audience to recognize their own environmental attitudes and behaviors through intimacy with these characters, their words, and their musical refrains.

Persephone’s operatic voice is sensual and lyrical. She is at first blithely unapologetic about her unseasonable desires, embodying our own human resistance to the limits of the seasons and the earth:

Living in the dark takes will. Irony.

A strong stomach for dearth, dearth, dried fruit.And no harm, time to time, to sing too much

in the sun, exotic plums, fresh blistered lemon

on the lips.

Later, she laments the damage that her choices have enacted around her, the “leaking seas, the thirst. / The heat-rash,” “this ever-warming bed,” and “the sweetest things / gone missing. Songbirds. Fisheries and favorite trees.”

Demeter, framed as the main storyteller of the opera, engages directly with the audience to help us understand “what happened” to Persephone and the world. She begins by telling us a version of the original myth:

What happened was, she was pulling.

Long ago. Pulling at something. A flower?Yes, maybe. Narcissus, it might have been.

And when its root gave way, what happened washer going below, cold

and swallow.Everyone knows

that part.

She then begins to recount, metaphorically, the environmental perversions that have occurred since then:

What happened was, much later, a different kind of pulling.

A string for a bell, sweets from a bowl, sheetsfrom a bed. This pulling was much easier

than with that tough root. And she went on and on,dingdingding, syrup, and silk

all day long. A taste for morethan mysteries.

Demeter becomes fiercer and more fragmented, and as the goddess of earth and harvest, her storytelling nods to industrial agriculture’s chemicals and monocultures: “What happened was antibiotics. Later. Neonicotinoids / and corncorncorn. My atrazine fog.”

Meanwhile, a chorus of Everyperson human “We’s” enables and is seduced by Persephone, caught up in her indulgence and her spiraling dissolution. These hapless, playful We’s, good-intentioned but fuzzy on the big picture, speak with some levity running through their colloquial, sometimes absurdist prose poems. In their opening appearance, the We’s recount their sanguine, exceptionalist early reaction to Persephone’s unseasonal appearances:

At first, it was all biergartens and orange Dreamsicles. She wasn’t supposed to be around now – these were her months to be away with him, eating stones and stroking clocks. Or whatever she did with him. But she had chosen us…. We made merry, made noise, made hay, made out like magpies. Then she was gone again. She left us, each time, with our suddenly bared skin and our chosenness, with our schoolchild sensation of having gotten away with something slight but delicious.

But the We’s too soon grow queasy at what they see, and they are reduced to reciting a litany of horrors: “Fire ants. Wildfire. Food riots. / Heat stroke. Too many ticks. Green crabs. Rotting ice. / Lymphoma. Sticks and stones. Drowning, thirsting. Dead zones.” Later, in their grief and guilt at what humans have wrought, the We’s disavow all human creations—gods, story, and even language itself. But ultimately, a trip underground, a dose of humor, and a reemergence into wonder bring them back to agency and hope.

And how does climate crisis translate musically, in this modern myth? Composer Nye wrote with an ear to entice, disorient, dismantle, and, ultimately, offer solace, beauty, and hope. He scored Persephone for quartet—violin, viola, cello, and oboe—in post-Romantic style, rich in contrapuntal complexity, dissonance, and fragmentation. For a story so dramatic and yet so close to our everyday lives, Nye chose the intimacy of a chamber ensemble coupled with the grand musical influences of Wagner, with his complex textures, leitmotifs, and epic chords, and the broken, punctuated landscapes of Elliot Carter.

Demeter’s accompaniment begins in slow, tender, mournful concern, rich in braided laments on the strings, while Persephone is drawn in soaring violin motifs, and the We’s—the characters perhaps most like most of us in all our human curiosity and clumsiness—are voiced with playful, careening, accelerating pizzicato, skittery vibrato, and trills on the oboe. In performance, the music of Persephone was filtered live through a digital delay; the aural effect mirrored the disjunction and crisis—as well as the beauty—of our modern natural world. This delay sent reverberations of the music and words echoing beyond their initial sounding, simulating the inexorable ripple effects of our own words and actions on our environment.

As the story enters the deepest darkness of the third movement, the musical motifs break down, becoming more disjointed and dissonant, representing both the humans’ emotional turmoil and the chaotic destruction of the landscape around them. But once the We’s recognize that they cannot stay in the dark of their passive grief and guilt, that they must live and act in the world, and that they must find ways to tell and act upon “what happened,” the music restores its original motifs and harmonies, which nevertheless remain tinged with dissonance.

The purpose of the classical Greek mysteries, which brought initiates into the dark and back to the light, was to reconnect them with their senses, their ancestors, and their capacity for wonder. Our purpose was similar in creating Persephone.

As they return into the light, the We’s find themselves newly astounded by every detail of the life around them. They gather around a sleeping Persephone and are “amazed at things we had never noticed”—the thrum of her pulse, the faintest sound of her breath. And they find new wonder in their understanding that she is alive:

Alive. We spoke the word over and over. The life of her rose in our chests, caught and rung in our throats.

The opera leaves us with a call to find attention and reverence for even the smallest facets of life around us, as a place to start to both heal and act.

Immersion: Through the Eyes of an Octopus. (A collaboration with composer Marianna Filippi for KIMI Ensemble; performed in Copenhagen, Denmark, and Camden, Maine, 2022. Watch a video of the Copenhagen performance. The author’s libretto can be found at Filippi (“Compositions”).

While the complex narrative of Persephone was written to initiate audiences into a ritual experience of climate crisis, the short composition Through the Eyes of an Octopus was meant to immerse them in the bodily and sensory experience of one impossibly wondrous creature—and so to inspire curiosity, awe, and fellow-feeling.

I first met my Octopus collaborator, composer Marianna Filippi, in 2019 in Portland, Maine, after a performance in which I collaborated with the cellist Eugene Friesen, reciting poetry by Rumi and my own poems as he performed with several Portland musicians. Filippi, originally from Midcoast Maine but now based in Copenhagen, has composed often on environmental themes. Some of her works include Jordens Sjæl, a composition for symphony orchestra that Filippi calls “a versatile celebration of the majesty of the Earth”; The Trees Speak Without Words, which “sonically illustrates the biological science of tree systems, and how they communicate through their roots”; and Abyssal Beings, a chamber work for accordion trio that celebrates bioluminescent creatures called the Sea Angel, a species of translucent sea slug, and the Tomopteris, a type of segmented sea worm (Filippi, “Compositions”).

Not long after the Friesen performance, Filippi reached out to me to propose a collaboration on a choral commission honoring Maine’s natural land- and seascapes for the state’s 2020 bicentennial celebration. (The performance was delayed for three years by COVID, but finally premiered in December of 2023). Our next collaboration, Through the Eyes of an Octopus, was inspired by Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed’s popular film My Octopus Teacher and philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness. We created our composition as a commission for KIMI, an Icelandic-Greek trio also based in Copenhagen.

My intention for the libretto was to immerse listeners in the uncommonly other neurological, biological, and sensory experience of moving through and sensing the world as an octopus over the course of a day. Through this immersion into the cephalopod’s sensitivity and playfulness, I hoped to make familiar her strangeness, and so to inspire wonder, empathy, and intimate affection for this being—and so too, perhaps, for the lives and health of her kelp forest habitat, her neighbors, and the larger ecosystems of which she is a part.

Filippi scored Through the Eyes of an Octopus for mezzo-soprano, accordion, and percussion (including vibraphone and marimba). In her composer’s statement, she writes that the composition “focuses on the octopus’s extraordinary sensory abilities, its shape shifting and color-changing abilities, the eight semi-autonomous tentacles, and its capacity to be sensitive and to express emotion” (Filippi, “Compositions”).

Filippi’s musical approach was playful and complex—as rich, by design, as a vibrant ocean ecology—and placed unique challenges on the vocalist and musicians, all three of whom were asked to wield percussion instruments (an ocean drum, bags of marbles, Tibetan cymbals, castanets, Chinese opera gongs, and stones) as well as to vocalize in whispers, sibilance, pops, and sudden intakes of breath. Filippi writes that she chose to score this elaborate auxiliary percussion “in order to satisfy the virtuosity that the libretto, and the octopus, required” (Filippi, “Compositions”). The score begins slowly and rhythmically, in an extended seascape sequence of slow ocean drum, marble bags, and cymbals unaccompanied by vocals, bringing listeners down to the ocean floor.

I had my own fascinating challenge as the librettist: how to lyrically simulate the experience of a creature that has semi-autonomous arms, that can shift color and texture as it moves across different features of the sea floor, and that can essentially see and even taste with its suckers? In drafting the libretto, I drew on synesthesia, onomatopoeia, rich imagery, and cephalopod-esque neologisms, in playfully expressionistic constructions meant to bridge humans’ sensory knowns with the marvelous unknown.

The libretto begins with the octopus waking and uncurling her tentacles from her cave, as the vocalist slides across the entirety of her vocal range, under the musical direction “noticeably out of time/lagging—almost yawning, as if just waking up”:

Unspool Uncoil Unwind

From the dream sea

From the shell roomSense the sea

Writhe-mind reach sucker-kiss clutch finger-lip lickmoon-tongue to moon-tongue to moon-tongue to moon-tongue….

(Grumbling, Through the Eyes of an Octopus)

Through the lyrics, the octopus proceeds to swim and shift her way across the ocean floor, “becoming,” through her incredible powers of camouflage, a variety of objects and beings—including kelp:

Slither swim swoooosh through the sea

Crawl writhe wooooosh over the kelp

Slither swimBe the kelp!

glide green wrinkle clench stipple skin

flutter frond-arms and swaaaayyyy.

(Grumbling, Through the Eyes of an Octopus)

After a series of such protean adventures (including some playtime, during which she wriggles her arms up into a gleaming school of fish) the octopus returns and re-coils into her shell cave. The music reprises the slower seascape rhythms from the overture, the octopus drifts off, and her “dreamskin” begins the color shifts (“umber drift violet drift blue”) that sometimes accompany a cephalopod’s sleep (Grumbling, Through the Eyes of an Octopus).

Filippi and I wrote Through the Eyes of an Octopus hoping that as listeners became immersed in the creature’s day, they might feel similarly to how we ourselves felt in researching, imagining, and writing about octopuses. We hoped that their response would begin in curiosity, be moved to awe, and land in delight and affection. And we hoped that listeners might be moved to immerse themselves so intimately in the lives of our other fellow beings as well. This sense of bodily immersion in a nonhuman being, we believe, could be a powerful practice in our environmental moment, as biospheric health hinges upon decentering human primacy and growing our sense of community and solidarity with other beings. This decentering might best begin not with the intellectual brain, but with our most primal senses and wonder.

Invitation: “Snow, Millennia, and Blue.” (A work-in-progress collaboration with composer Marianna Filippi, to be performed by choir and cello octet in Copenhagen, summer of 2024.

The melting of Arctic glaciers is among the most visceral and epic tragedies of our environmental crisis, and yet it often feels difficult to grasp at full scale. When Filippi reached out to me about a collaborating on a piece about glaciers, I knew I wanted the libretto to invite listeners into closer proximity and intimacy with a glacier, and into opportunities to feel, mourn, and even be changed by a glacier’s essence.

To do so, my first decision was to make glaciers an animate entity and to let them voice the libretto in the first-person plural “we.” The question of how a collective of glaciers might vocalize, and what they might say, was an interesting one. I found it seemed right to have them speak in simple, strong, open phrases that could be held in long tones.

The glaciers’ voice evolved to hold rich verbal music, including vowel assonance, which seemed resonant with their capacity to hold and vibrate with water and scree, and onomatopoetic alliteration, expressing their incredible powers for “[s]craping stone to till and trough.”

The libretto contains six short movements, followed by a coda; each movement begins with an invitation to “hear” something about glaciers, affording glaciers a storytelling and teaching role. The first movement, “Blue,” aims to at once revere and demystify their unearthly glacier blue by telling of the hue’s origins: “Hear, how our blue was born,” the glaciers offer, then recount:

Snow fell. And snow fell. And snow fell.

And ice pressed close and long.

So close, so long

millennia

our crystals were transformed.And so there was a blue

born in our ice.Essence blue

Compass blue

Pulse blue

In the second movement, “Oracle,” the glaciers speak of the stories they hold of history:

Every season leaves a layer

of what has passed.

Snowfall and spoor, fossil and ash

Bubbles of atmosphere and breath

They then make clear the insights they offer of both past and future:

Know our core and learn the gone

Know our core, foretell the world

The third movement reminds us that glaciers are active and constantly moving—moving over the earth, moving mountains and sand, and even moving within themselves, as they vibrate with the objects they carry and traverse. They announce that they are “[s]ounding tones with every stone we touch.”

Because I hoped to bring listeners into a closer relationship with glaciers before confronting them with the glaciers’ crisis, I waited until the fourth and fifth movements to bring the catastrophe of melting into the glaciers’ voice. “Hear, how our blue is going,” they offer in the fifth movement. “How our blue is ghost.” And as they earlier explained the origins of their blue, they now explain the origins of their melting, repeating lines as in a dirge:

Whims and risks and reckless gases rise.

Our sphere warms.So high, so warm, we pool, we pour, we rush.

So high, so warm, we pool, we pour, we rush.And so there is our going. And so there is our ghost.

And so there is our going. And so there is our ghost.

The fifth movement, “Louder,” elaborates on the melting by relating the incredible fact that as glaciers melt faster, they are growing louder:

Our sound is swelling, growing swollen

melting, running, roaring, rumbling, quaking, cracking, calving, crashingGoing and ghost, we grow deafening

Going and ghost, we could rouse the gone

In the sixth movement, “You,” the glaciers present their most poignant offer of wisdom: “Hear, how we may move in you.” They describe how, with attention and reverence, our close knowing of the glaciers might change us for the good:

Allow our blue within, lucent

Learn our core, our oracle

Thrum your fibers with our force

Know us, going and ghostAnd keep us, close and long.

So close, so long,

your being may transform.And may there be a blue

…born in you of our ice.

A blue of reverence, balance, awe

Filippi plans to score this libretto for cello octet and lanspil, a traditional Icelandic drone zither. The choir will also take part in instrumentation, via nonverbal and manual vocalizations, to help conjure and animate a glacier’s sibilance, cracks, pops, and fizzes.

We hope that those who listen to “Snow, Millennia, and Blue” will be moved to understand that glaciers are constantly moving, that they hold our planet’s stories, and that they possess, in a very real sense, voices and even animacy. This composition will invite audiences to consider that there is much we can learn from glaciers, and even an essence we might embody, for the greater empathy and balance of all in the natural world.

Conclusion: Writing through the Anthropocene

One of the greatest challenges for anyone engaging with environmental themes in our moment is the question of how to balance the horror with the exhilarating beauties of our natural world. And it will take an intricate ecology of creators, projects, performers, tellers, and listeners to help us learn this balance and move forward toward solutions. The making and receiving of environmental opera represents one nexus of ways that we might engage, in community, with the vicissitudes of our natural world and our complex relationships within it. Works of environmental opera can initiate us into ritual journeys through environmental crisis, grief, and enlightenment. They can immerse us in experiences that incite renewed wonder and love for our fellow beings. And they can invite us to more intimately know and even be transformed by the creatures and forms of the natural world, these miraculous systems that are alive all around us.

“Alive,” we too might marvel, just like the Persephone chorus, at these wondrous webs that hold and inspirit us, that we depend upon for our lives. We might even, like the Persephone chorus, be moved to speak, sing, or hear such words over and over, as in a hymn or psalm. Both the words and their music can help bring us closer to our natural world—which is to say, closer to home.

WORKS CITED

Ehrlick, P., & Reed, J. (Directors). (2020). My Octopus Teacher [Film]. A Netflix Original Documentary.

Filippi, Marianna. “Compositions.” Marianna Filippi Music, https://mariannafilippimusic.com/music. Accessed 31 October 2023.

Filippi, Mariana (composer) and Grumbling, Megan (librettist). Through the Eyes of an Octupus. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=–7pCEfSGXA. Accessed 31 October 2023.

Godfrey-Smith, Peter. Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness. First edition. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

Grumbling, Megan. Persephone in the Late Anthropocene. Acre Books, Cincinatti,2020.

Grumbling, Megan. Through the Eyes of an Octopus. “Compositions,” Marianna Filippi Music. https://mariannafilippimusic.com/music. Accessed 31 October 2023.

Nye, Denis. Persephone in the Late Anthropocene. https://www.hingeworks.org/persephone-in-the-late-anthropocene. Accessed 31 October 2023.