Hawaiian Luas: A Sacred Feast or a Party in Paradise?

Students in Dr. Karen Metheny’s Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts this month. Today’s post is from Ashley Lopes.

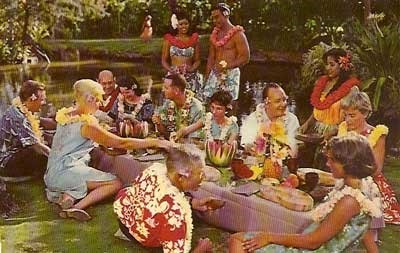

When I think of Hawaiian luaus, I think of men, women, and children dancing, singing, and eating together at one glorious table. I imagine a lavish, tropical feast, accompanied by games, music, and hula. In our Anthropology of Food class, we learn how food can symbolize identity, social values, and cultural transformation. Hawaiian luaus for example, reflect Hawaii’s shift in foodways.

Today’s movies, tv shows, and books all portray the luau as a party in paradise. In the article “Luaus, Authenticity and the Anthropology of Food,” however, Kaori O’Connor (2008) reveals that the modern-day conception of Hawaiian luaus is highly romanticized and idealized. Before contact with Western cultures, eating and feasting in Hawaii were linked to religion and sacrality – to feeding the gods and offering sacrificial foods. Men and women of all social classes were regulated by food taboos and restricted from eating the same foods at the same tables. Men oversaw the gathering, fishing, provisioning, and production of food. Women, on the other hand, were not allowed to take part in any of these activities. They had very little freedom in what they could do. During the traditional luau, food was served cold, people sat on the floor, and everything was eaten with hands.

Today’s movies, tv shows, and books all portray the luau as a party in paradise. In the article “Luaus, Authenticity and the Anthropology of Food,” however, Kaori O’Connor (2008) reveals that the modern-day conception of Hawaiian luaus is highly romanticized and idealized. Before contact with Western cultures, eating and feasting in Hawaii were linked to religion and sacrality – to feeding the gods and offering sacrificial foods. Men and women of all social classes were regulated by food taboos and restricted from eating the same foods at the same tables. Men oversaw the gathering, fishing, provisioning, and production of food. Women, on the other hand, were not allowed to take part in any of these activities. They had very little freedom in what they could do. During the traditional luau, food was served cold, people sat on the floor, and everything was eaten with hands.

So where does the modern luau come in? Why have Hawaiian food taboos been forgotten? When American missionaries arrived in Hawaii, they took it upon themselves to “civilize” and change the foundational principles of Hawaiian society. Missionary wives taught Hawaiian women how to cook refined, Western-style food. Tourist promoters used postcards to publicize Hawaiian luaus as lavish (but civilized) feasts that catered to Euro-Americans and Asian immigrant groups. The luau menu began to offer multi-cultural dishes – a fusion of macaroni and potato salad, fried rice, sushi, and barbeque steak. O’Connor argues that luaus continue to be an obligatory part of the Hawaiian tourist experience because they transport the eater to an exotic, purist realm. She makes an interesting point that authenticity is relative and ever-changing. Over the course of Hawaii’s history, the traditional luau has been molded and reinvented into a mashup of different cultures, food practices, and flavors.

Works Cited

O’Connor, Kaori. 2008. “The Hawaiian Luau: Food as Tradition, Transgression, Transformation and Travel. Food, Culture, and Society 11(2): 149-172.

Simple Sustainability in an Unsustainable World

The next in our series of posts from Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) is from Shannon Fitzgerald.

In Everyone Eats, author E.N. Anderson (2014) urges conservation, sustainability, and efficiency to feed the world. This prompted me to reevaluate my life. How am I practicing sustainability and conservation? How am I respecting the planet, so that others can enjoy it and eat? A strong believer that something is better than nothing, and that a little can go a long way, here are three ways that I am working on sustainability:

1. Planting/growing food

Living in an apartment in Boston can make this a little difficult because of limited space, limited sunlight, and limited outdoor access. As much as I would love to have a flourishing garden with a variety of fruits and vegetables, I have had to adapt this dream to my current living situation. Herbs are easy to care for, and do not require much space. My rosemary plant sits in a small pot on my windowsill. Not only does it add decoration and fresh life to my room, but it also provides me with flavor for my meals. Sharing fresh-grown herbs and vegetables with my friends is another way that I keep my food local; in exchange for rosemary and a home cooked meal, I am provided with off-the-vine tomatoes and basil.

2. Reduce, reuse, recycle

Reduce, reuse, recycle is a common mantra that most have heard since early childhood, but it isn’t always implemented. I reduce waste by buying fresh foods with limited to no packaging, and try my hardest to buy only what is needed and use it all to limit food waste. Reuse is a simple, easy step. Drinking from a refillable water bottle, taking my lunch to work in reusable containers, and bringing utensils from home allows me to not only limit unnecessary waste but also reuse all of these. It saves money, time, and the environment. In cases where reducing and reusing aren’t possible, recycling and composting are great ways to help the environment. I recently attended a composting workshop at the Boston Public Market, which explained how composting works and the different forms such as vermicomposting (composting with worms). If home composting is not a viable option, there are some companies in Boston that provide compost bins and schedule pick-ups for them as well.

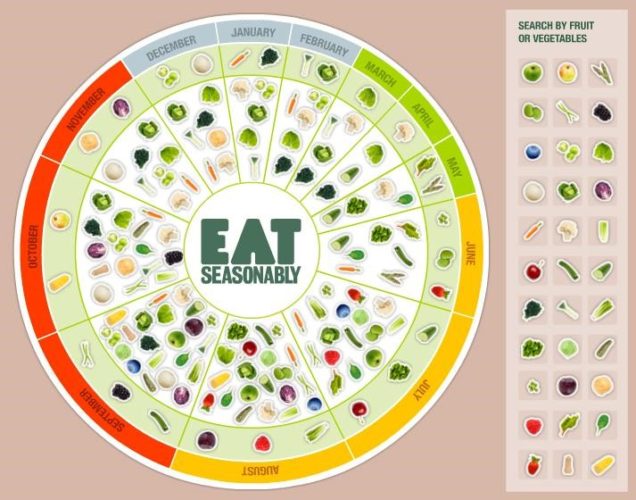

3. Buying in season (locally)

What is better than a tasty, well-cooked meal? A tasty, well-cooked meal made with local, in-season ingredients! Not only does buying seasonal fruits and vegetables save money, but it also tastes fresher and supports local farmers. Contributing to the local economy not only assists farmers, but also the planet through lessened waste of resources. Local food is being used, and hopefully as the local movement becomes more popular, less energy and fuel will be wasted in transporting exported goods. To be honest, this does not always work out, judging by the amount of pizza I’ve eaten recently! It’s an ongoing process for me and one that I am hoping to get better at.

Any shift to a more sustainable lifestyle helps, and does not need to involve a complete overhaul. As always, I can and am working on doing more, but these three ways that I have adapted my habits were all simple, and they make me feel like I’m part of the solution instead of the problem.

Commensality at the Lunch Table

The next in our series of posts from Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) is from Gastronomy student Meghan Russell.

If you read popular newspapers or magazines, you may have seen that the American lunch hour is being threatened. More and more Americans are working through their lunch hour, skipping it altogether, or eating at their desk as they continue to work. One place where lunchtime is still alive and well, however, is in the school cafeteria. While I won’t be speaking to the cafeteria per se, I will be examining elementary school lunch-time as experienced during a class field trip to an area farm. I work as a Farm Educator at this farm and therefore have the opportunity to observe many students interact as they each lunch at their end of their field trip.

Field trips offer an interesting look into school lunches because there is no hot lunch option provided by the school. Everyone is eating something brought from home. This creates immediate differences between each of the students that can be broken down and analyzed at various levels. For one, each student brings his or her lunch in its own unique receptacle. While the classic brown paper bag is still a popular option, the simple plastic lunch box with a pop culture icon on the front is gone. These have been replaced by a variety of nylon and zip-up options in a variety of sizes and colors, often with matching water bottles. Some students have individual compartments built into their lunch box to separate out their items, while others have individual plastic containers that hold the various pieces of their lunch within. In addition to these fancy, sustainable, and eco-friendly options some students also use a simple plastic grocery bag or a gallon-sized Ziploc bag.

Within these various lunch receptacles are a wide range of food items. Some students still bring the classic sandwich with a bag of chips and a piece of hand fruit. The old stand-by of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, however, has been replaced by sunbutter and jelly or a lunch meat sandwich to accommodate for allergies. Some students have expensive berries, organic squeeze poaches, and Lunchables. Others have ethnic items representative of the immigrant status of the parents, the student, or both – a bag of sushi, a noodle dish with chop sticks, or a Vietnamese sweet cake.

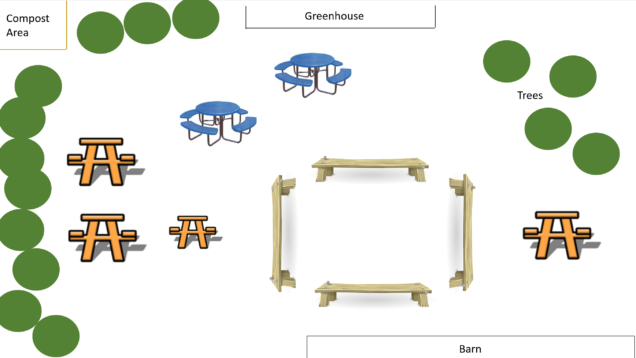

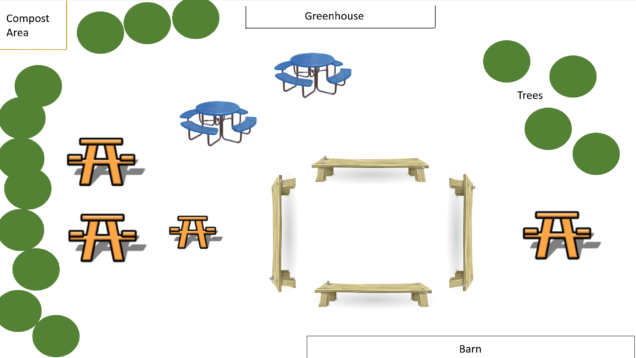

In addition, a student’s choice of seat for lunch impacts his or her lunch experience. This particular area consists of multiple picnic tables placed around a square of wooden benches. If a student decides to sit on the bench, she must either hold her lunch on her lap or place it down next to her. This orients her lunch experience. Will she engage in one-on-one conversation with the student sitting next to her, who may have also placed her lunch down on the bench so that they are facing each other in a mini-conversation? Will she face forward in silence? Or will she try to yell across the open space to someone on the other bench? Sitting at one of the picnic tables creates larger conversations involving the upwards of eight or ten students that can fit at the table.

Among all these differences, the students are all hungry, and it is lunchtime. After being split up in groups all morning for their field trip, the students are happy to be back together. Watching them eat lunch, there doesn’t seem to be any acknowledgement of differences between what they are eating for lunch or what their lunch came in. Each is engaged in his or her own experience yet they are also all eating lunch together. To engage in commensality, it doesn’t matter what any one individual is eating. What matters is the socialization that is occurring, the sharing of space and time.

Explore the Art and Craft of Japanese Culinary Tools

We continue with our series of posts from Students in Dr. Karen Metheny’s Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) .

The Fuller Craft Museum in Brocton, MA, is currently exhibiting Objects of Use and Beauty: Design and Craft in Japanese Culinary Tools. The exhibition has been curated by Debra Samuels and Merry White. Ms. Samuels is a cookbook author, food and travel writer and cooking teacher. Dr. White is a professor of Anthropology at Boston University.

For thousands of years, the Japanese have combined the art and craft of food preparation with focus and continual pursuit of perfection - kodawari. The refined culinary tools on display reflect the careful consideration that has been put into every aspect of their function and form. Made from wood, metal, clay and other materials, each of these objects are perfectly designed for their designated tasks. They are also exquisitely beautiful. The exhibition brings them to life with video recordings of the craftsmen making these objects, and chefs using them in food preparation. The exhibition is highly recommended for anyone interested in Japanese culture and craftsmanship, especially in the culinary world.

The exhibition runs through October 28, 2018. The Fuller Craft Museum is set in an idyllic wooded location next to a lotus pond. Located three miles off Route 24, it is also accessible by public transportation. The Museum is open from 10am to 5pm, Tuesday through Sunday. Admission is $10 for adults, $5 for students and free from 5pm to 9pm on Thursdays. JJ’s Caffe is a great brunch spot located about a 5 minute drive from the museum.

Fika: Taking a Break in Sweden

Students in Dr. Karen Metheny’s Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts this month. Today’s post is from Norma Tentori.

During discussions and readings in Anthropology of Food, the class delved into many different human cultures and their social traditions that surround food. A topic I found especially interesting was how cultures can have such distinctly different rituals and traditions around a certain food item. In this instance I am talking about coffee. These discussions caused me to reminisce and reflect on a recent trip overseas to Sweden when a new word that was deeply embedded in both coffee and tradition was introduced to me: fika.

During discussions and readings in Anthropology of Food, the class delved into many different human cultures and their social traditions that surround food. A topic I found especially interesting was how cultures can have such distinctly different rituals and traditions around a certain food item. In this instance I am talking about coffee. These discussions caused me to reminisce and reflect on a recent trip overseas to Sweden when a new word that was deeply embedded in both coffee and tradition was introduced to me: fika.

Coffee in Swedish translates to “kaffe,” but pairing coffee with something to eat is defined as “fika” - both a noun and a verb. It is a part of Sweden’s tradition that many engage in at least once daily.

During my time this past summer in Gothenburg, it seemed as if every map and brochure defined the Haga neighborhood as the ultimate place to engage in fika. Haga is also one of the oldest and most popular districts in Gothenburg.

A cobblestone pedestrian street threaded through the neighborhood lined with wooden houses, plenty of shops and, most important, a cafe on seemingly every corner. Signage proved we had reached the correct destination as it stated “Haga: cosy shopping & fika.”

After receiving a recommendation from a local shop owner, we decided to have our first fika break after shopping at Cafe Husaren. The cafe is most famous for its hagabullen rolls. Hagabullen is most similar to a cinnamon roll, and the ones at Cafe Husaren are known specifically for their size and distinct flavor, most similarly compared in size to a small pizza as they barely fit on a dinner plate and are certainly a ‘meal’ to be shared.

Cafe Husaren is a Swedish cafe that also offers prepared foods and, most important for our fika break, coffee. The hagabullen are warm from the oven, and a cinnamon and clove scent wafts through the air as soon as you walk through the entrance. They have no icing compared to our traditional expectation of cinnamon rolls, but are instead dotted with pearl sugar which gives the roll an extra punch of sweetness.

As we attempted to get through the pizza-sized hagabullen and drank our coffees on one of the cafe’s outdoor tables, we enjoyed watching the people who walked through the city and completely disconnecting ourselves from the otherwise busy parts of the city.

As we attempted to get through the pizza-sized hagabullen and drank our coffees on one of the cafe’s outdoor tables, we enjoyed watching the people who walked through the city and completely disconnecting ourselves from the otherwise busy parts of the city.

For Swedish social engagements, fika is the ultimate food custom as it represents their love and passion for coffee. Fika symbolizes tradition. The comfort of fika therefore does not simply lie in the warm cup of coffee and baked treat you are eating, but in the emotional connection that is tied to slowing down and truly taking a break. Asking to grab a coffee with someone in English does not carry the same meaning as asking someone to fika. Fika does not exist for the purpose of having a snack or an afternoon caffeine pick-me-up, but rather exists to appreciate slow living, spending time with others and simply taking a break. The coffee and food that come along with it are a bonus.

Whether we choose to engage in fika on our own or with others, we can all take a little bit of inspiration from this Swedish tradition by making our daily coffee break a designated time to slow down, relax or socialize with others.

Works cited

Brones, Anna, and Johanna Kindvall. 2015. Fika: the Art of the Swedish Coffee Break, with Recipes for Pastries, Breads, and Other Treats. Ten Speed Press.

Commensality at the Lunch Table

We continue with our series from our summer class, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641), with this post from Meghan Russel.

If you read popular newspapers or magazines, you may have seen that the American lunch hour is being threatened. More and more Americans are working through their lunch hour, skipping it altogether, or eating at their desk as they continue to work. One place where lunchtime is still alive and well, however, is in the school cafeteria. While I won’t be speaking to the cafeteria per se, I will be examining elementary school lunch-time as experienced during a class field trip to an area farm. I work as a Farm Educator at this farm and therefore have the opportunity to observe many students interact as they each lunch at their end of their field trip.

Field trips offer an interesting look into school lunches because there is no hot lunch option provided by the school. Everyone is eating something brought from home. This creates immediate differences between each of the students that can be broken down and analyzed at various levels. For one, each student brings his or her lunch in its own unique receptacle. While the classic brown paper bag is still a popular option, the simple plastic lunch box with a pop culture icon on the front is gone. These have been replaced by a variety of nylon and zip-up options in a variety of sizes and colors, often with matching water bottles. Some students have individual compartments built into their lunch box to separate out their items, while others have individual plastic containers that hold the various pieces of their lunch within. In addition to these fancy, sustainable, and eco-friendly options some students also use a simple plastic grocery bag or a gallon-sized Ziploc bag.

Within these various lunch receptacles are a wide range of food items. Some students still bring the classic sandwich with a bag of chips and a piece of hand fruit. The old stand-by of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, however, has been replaced by sunbutter and jelly or a lunch meat sandwich to accommodate for allergies. Some students have expensive berries, organic squeeze poaches, and Lunchables. Others have ethnic items representative of the immigrant status of the parents, the student, or both – a bag of sushi, a noodle dish with chop sticks, or a Vietnamese sweet cake.

In addition, a student’s choice of seat for lunch impacts his or her lunch experience. This particular area consists of multiple picnic tables placed around a square of wooden benches. If a student decides to sit on the bench, she must either hold her lunch on her lap or place it down next to her. This orients her lunch experience. Will she engage in one-on-one conversation with the student sitting next to her, who may have also placed her lunch down on the bench so that they are facing each other in a mini-conversation? Will she face forward in silence? Or will she try to yell across the open space to someone on the other bench? Sitting at one of the picnic tables creates larger conversations involving the upwards of eight or ten students that can fit at the table.

Among all these differences, the students are all hungry, and it is lunchtime. After being split up in groups all morning for their field trip, the students are happy to be back together. Watching them eat lunch, there doesn’t seem to be any acknowledgement of differences between what they are eating for lunch or what their lunch came in. Each is engaged in his or her own experience yet they are also all eating lunch together. To engage in commensality, it doesn’t matter what any one individual is eating. What matters is the socialization that is occurring, the sharing of space and time.

Recreating the Taste of Mexico in a Crowded Cambridge Kitchen

Students in Dr. Karen Metheny’s Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts this month. Today's post is from Sam Dolph.

In April, my partner and I decided to finally take the frozen banana leaves out of our freezer—purchased many months before —and to dedicate a whole day to making “authentic” Mexican tamales. Having moved to the U.S. three years ago, my partner, who is from Mexico, is very understandably unsatisfied with the Mexican food here in Boston. Anywhere that puts rice inside of a burrito is a mockery of her cuisine, not leaving many options available. Thus, her cravings for Mexican food—tacos, chilaquiles, mole—are only truly satisfied when she makes the dishes herself. So, knowing the labor-intensive process that lay ahead, we made a list of the ingredients we needed and set out to recreate one of her most beloved meals.

Making the tamales was not as easy as finding the ingredients, which we secured at Market Basket and La Internacional Foods, a small Latin American market, both in Somerville. In addition to the banana leaves, we needed achiote paste, salsa ingredients, chicken, and masa dough. After purchasing all of the ingredients, we came home and immediately blended up the salsa ingredients, which we threw into the slow cooker with the chicken and achiote paste. Next, we made the masa dough, which just meant adding the right amount of water, lime juice, and salt to the flour. Despite following a recipe, our proportions were off so we ended up having to add more of everything until we reached the desired consistency.

We then prepared the banana leaves, which was the most difficult part of the process. Banana leaves must be cleaned well before cooking, but they are so delicate that one must clean them very slowly and carefully. We soaked them in water and then softly scrubbed each leaf with a sponge before laying them to air dry. Afterwards, we had to gently rub each leaf with a paper towel to ensure total dryness. We then had to carefully cut the damaged edges of the leaf and then snip them further so they were the correct size. Because the leaves are so fragile, all cuts must be made slowly and deliberately or the entire leaf could be ruined (which we did, multiple times). Needless to say, the banana leaf process lasted the entire four hours.

Finally, it was time to put the tamales together. We first had to warm the clean banana leaves straight on the burner so they could soften, and then we added a layer of masa dough, followed by a layer of the slow cooked chicken, which was then covered by another layer of masa dough. We carefully wrapped the rest of the banana leaves around the chicken-filled dough, and tied each tamale together with a thin string of banana leaf we had cut from the ends of the bigger leaves. We then piled all the tamales into a steamer basket and steamed them for one hour. Altogether, the cooking process lasted around 6 hours. By the time we pulled the tamales out of the steamer, we were starving, cranky, and tired.

Could we have just bought a package of frozen tamales from Trader Joe’s instead, which would’ve taken 30 minutes at most? Maybe. But this wouldn’t have truly satisfied my partner’s craving for Mexican food. The 6-hour process of making tamales meant connecting with her culture as a whole, rather than simply eating it. Filling our bellies with tamales was an added bonus (they were, obviously, delicious), but this entire process was more of an exercise in finding home through food and affirming her Mexican identity in a new setting, than it was about simply eating tamales.

Reflections from the 2018 AFHVS/ASFS Conference

We’re back from the big annual food conference, hosted this year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The conference is hosted by two academic organizations: The Agriculture Food and Human Values Society and the Association for the Study of Food and Society (hence, the conference is called AFHVS / ASFS). Current BU Gastronomy students attended and presented at the conference, and we asked them to share about their experience; read on to learn about how this conference experience is a great experience for any gastronaut, and tips and tricks for attending future meetings. Thanks to Alex Cheser, Esther Martin, and Ariana Gunderson for their comments.

What was your favorite moment of the conference?

Alex: Oh, gosh, this is hard. I can narrow it down to three moments that are my favorite for different reasons. First, I had never been to a university or program so vocal and inclusive about the area’s connection to its native peoples. From the Land Acknowledgement in the program to the amazing banquet dinner menu, the influence and presence of the Hooçak Nation was visible, revered, and welcomed in collaboration. Second, I was so happy that the LGBTQ social event I planned went so well. I just reached out to the organizers at UW on a whim and they were so receptive and excited. This kind of meet up hadn’t happened at AFHVS/ASFS before despite the visible presence of queer folks, so it was quite rewarding to feel the solidarity among the tiny group. Finally, and more selfishly, I revere the feedback I got from my presentation. I submitted it and presented it as a work in progress hoping to get constructive feedback and that’s exactly what I got and I kept getting it over the conference, even during the last event of the conference - two days after I’d presented. This is my second time at the conference and it’s such a supportive and uplifting environment.

Esther: My favorite moments were interacting with people I'd only admired from afar. I met and

spoke to some of my foodways/folklore heroes. Additionally, I got to bounce my ideas of other, more experienced scholars and get feedback, while connecting with peers going through the same grad school process as myself.

Ariana: At the welcome dinner, as I sipped local craft beer with a new friend, he reached out to a person passing our table. He cried out, “Lisa! How have you been?” and I realized which Lisa this was – Lisa Heldke, one of my favorite food studies authors. She turned to introduce herself to me and I said, “Hello! I’m Ariana Gunderson from BU’s Gastronomy Program. I’m quoting you in my presentation tomorrow!” Then we discussed the article I referenced in my talk - how often do you get to discuss a published text with its author!? Apparently, at AFHVS / ASFS, all the time!

How did this conference implement skills or themes from your Gastronomy degree?

Ariana: Amazingly, I was able to literally implement my Gastronomy work by presenting my research from my Introduction to Gastronomy course! But interacting with other scholars was the best way to apply my degree: In round-tables and post-panel Q&As, I watched other scholars work through questions and research findings just like we do in class. I could put faces to names of so many people whose work I’ve been reading since I started this program. Honestly, I was a little star struck! But Food Studies is such a welcoming discipline, everyone is open and friendly. Leading scholars listened thoughtfully as I described my research and joked with me about kombucha. Just go up and introduce yourself!

Esther: The conference emphasized the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to food studies. Nothing is ever just about food, and all parts of food intersect. Food policy can learn from food history while food justice can utilize skills of food folklore. We are not isolated in our specializations, but rather united in the common theme of food as a form of education and social change.

Alex: Most of the sessions I attended focused on food policy or restructuring the food system and agriculture. Having taken all three of Dr. Ellen Messer’s food policy courses in the program, I felt very prepared as I heard each presentation and could easily contextualize it within the current food policy landscape. I definitely would have felt a little overwhelmed without that knowledge. I also felt empowered to ask specific, in-depth questions which, if you’ve had class with me maybe isn’t a surprise haha, but at a conference with ~professional academics~ I would normally be a bit quieter.

What advice would you have for a gastronaut considering attending future ASFS conferences? Any dos or don’ts?

Esther: Definitely submit a proposal, even if you don't have an idea for a paper yet. Almost

everyone changes a bit beforehand, and many people present new research ideas that aren't finished or fully formed. If you can, meet the people you admire. Use social media as a way to reach grad students and young professionals. And have business cards! Even if they're quick ones from Zazzle, they'll have all your contact info on them so people can follow up with you.

Alex: Go! No matter where you are in your degree tenure and no matter if you plan to pursue academia or not, if you are able to attend this conference, you will not regret it. Presenting your own research is great practice and this is not an environment where you will be beat down if you haven’t considered something or read a specific work. Even if you don’t present your data, this is one of the two conferences (so I’m told) where the major academic work of re-figuring the food system to be more just, equitable, and sustainable is presented and teased out. (The other one is the Rural Sociology conference apparently). Anyone who is wanting to delve into food policy or food justice work will benefit to know what’s on the cutting edge of this research.

Ariana: Go if you can! Make it happen, you won’t regret it. Here are some tips: Before you go, look through the program of presenters and highlight any panels you know you want to attend (look for names you recognize). Bring business cards if you have them (but if you don’t do not worry). Prepare a three-sentence description of your research interests (vague is okay!) because people will ask you when you meet them. There are (limited) funding sources available from ASFS and BU (reach out to me or Barbara for more details) to help defray costs. If you join ASFS this year (2018) you are eligible to apply for funding from ASFS to attend the 2019 conference!

Guinea Pigs and Salchipapas and Potato Soup, Oh My!

Students in Dr. Karen Metheny's Summer Term course, Anthropology of Food (MET ML 641) are contributing guest posts this month. Today's post is from Madeline V. Long.

In March, I traveled to Vilcabamba, Ecuador, to visit my parents who were living there with friends for the winter. In regard to food, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I knew from talking to my dad that there would be plenty of guinea pig to eat, but beyond that offering, which I politely did not try, I had very few preconceived notions on what Ecuadorian food and cuisine comprised.

Vilcabamba is a small village in the southern region of Ecuador and is a sort of melting pot of expatriates. Because of this, there are a broad range of foods available to please many palates. When my parents picked me up from the airport, they had Pain Au Chocolate from the local French bakery for us to enjoy on our ride back to the village. For lunch, we went to a café that offered falafel and curries among other vegan and vegetarian things. That evening, we dined at a sort of western cowboy themed restaurant where I had surprisingly good pizza margherita and my mom had pasta primavera. Needless to say, these were not the kinds of foods I expected to be eating.

While in Vilca, as the locals call it, the most traditionally Ecuadorian dish I had was Salchipapas, a hot dog on top of French fries served with ketchup and mayonnaise. This dish is actually a popular street food originating from Lima, Peru, and has spread to other parts of Latin America like Ecuador and Boliva over the years.

It wasn’t until we were in the larger city of Cuenca that we would visit Tiesto's, one of very few restaurants in the country that offers Ecuadorian food. After we decided on the tasting menu, our waiter brought out ten small dishes, each filled with different varieties of stewed hot peppers, pickled vegetables, and other condiments to be eaten with bread and the meal we were about to have. Aside from these delicious accompaniments, the highlight of the meal was the Ecuadoran Potato Soup made with potatoes, onion, garlic, cumin, annatto, milk, cheese, and cilantro. We also had scrambled eggs with corn, sweet potato dumplings, and grilled meat.

While this restaurant is considered one of the best in Cuenca and Ecuador, it did not seem to be frequented by locals, most likely because it was more expensive than most places. How authentically Ecuadorian of an experience was eating at this restaurant if the only Ecuadorian people there were the ones working? I found myself thinking about the differences in culture and wondering if a local wanted to go out for traditional Ecuadorian food, would they be able to? Or, is that kind of food something they would only enjoy in their home, made by themselves, friends, or family? Here in New England, if someone wants to go out for dinner and enjoy regional cuisine, the options are endless. Why is it that in some countries, going out to eat means enjoying a cuisine different than your own and in others it might mean enjoying something familiar?

Summer Course Spotlight: Local to Global Food Values: Policy, Practice, and Performance

Local to Global Food Values: Policy, Practice, and Performance will be offered through Boston University’s Summer Term 2. This class will meet on Monday and Wednesday evenings, beginning on July 2 with a final class on August 8. To register, please visit http://www.bu.edu/summer/courses/gastronomy/ .

What are "good" foods and trustworthy standards and measurements of value? Who regulates or labels claims such as "local," "natural," "sustainable," or "(non)GMO" and why should consumers care? These are the basic policy (government), practice (food-industry), and performance (case study) issues course participants systematically probe and debate during this six-week Summer Term II BU Gastronomy seminar. Each week clarifies and compares distinct environmental, economic, cultural, political, and nutritional frameworks of value. Readings, discussions, and hands-on exercises aim to develop professional and personal knowledge and skills for those working in food research, production, marketing, or advocacy, or more generally interested in understanding the science and technology, language and cultural politics, guiding U.S. and global food systems. The course is open to master's level or advanced undergraduates.

Ellen Messer is an anthropologist and culinary historian with an extensive background in food policy and food justice issues. Her research interests encompass cross-cultural perspectives on human right to food; biocultural determinants of food and nutrition intake; sustainable food systems (with special emphasis on the roles of NGOs); and the cultural history of nutrition, agriculture, and food science, including the impacts of biotechnology on hunger. She has authored and co-authored several books on food policy, including Who’s Hungry? And How Do We Know? Food Shortage, Poverty and Deprivation (United Nations Free Press, 1998). Previously she was Director of the World Hunger Program at Brown University and a Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Messer is a Lecturer in Gastronomy at Boston University and has current faculty affiliations at the Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and at Brandeis University’s Department of Anthropology.

Ellen Messer is an anthropologist and culinary historian with an extensive background in food policy and food justice issues. Her research interests encompass cross-cultural perspectives on human right to food; biocultural determinants of food and nutrition intake; sustainable food systems (with special emphasis on the roles of NGOs); and the cultural history of nutrition, agriculture, and food science, including the impacts of biotechnology on hunger. She has authored and co-authored several books on food policy, including Who’s Hungry? And How Do We Know? Food Shortage, Poverty and Deprivation (United Nations Free Press, 1998). Previously she was Director of the World Hunger Program at Brown University and a Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Messer is a Lecturer in Gastronomy at Boston University and has current faculty affiliations at the Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and at Brandeis University’s Department of Anthropology.