Eating to Survive: Food on CBS’s Survivor with Castaway Lyrsa Torres

Have you ever wondered what it's like to eat on CBS' hit show Survivor? Lucky for you, BU Gastronomy's own Lyrsa Torres was a castaway on Season 37 (airing now) and she spoke to us about what it really means to fend for yourself on a remote island in Fiji.

This year, the Survivor teams were split into David vs. Goliath. Lyrsa, who grew up in Puerto Rico and has degrees in both Anthropology and Culinary Arts, was on the David team and was eliminated right before the tribes merged.

Before heading to the island, the castaways spend a week in the Ponderosa resort where they take part in interviews and pre-game preparation. The castaways are surrounded by their peers but are not allowed to talk to one another. They eat communally but cannot speak, which led to various silent judgements being made before the game even started. There, Lyrsa loaded up on pizza and actually gained 4 pounds before being sent to the island.

The castaways are given only a bag of white rice to sustain them for 39 days on the island. They are forced to ration the rice to last as long as possible while hunting and gathering the rest of their food. Lyrsa mentioned worms, lizards, larvae, and fish as possible sources of protein in addition to native fruits like papaya and coconuts. Known as the "serial crab killer," Lyrsa flexed her skills by finding and killing hermit crabs to share with her tribe. She spoke about the difficult question of calories versus labor - is the amount of calories in the food worth the labor it will take to catch it?

Food is much more than just a means of sustenance on the island. Besides strategizing, Lyrsa noted that food was all the castaways talked about. Finding and sharing food crated social bonds, and reminiscing on certain meals or wishing for specific foods was a common way to pass the time. Lyrsa craved cheese during her time as a castaway because it reminded her of her family, specifically her grandmother.

Many of the rewards for winning challenges were food, like chickens or eggs. Lyrsa explained how it was exciting to win, but much more exciting to be given food since the teams were deprived of it on the island. Although she doesn't like sweets, Lyrsa ate anything put in front of her.

After getting voted off the island, castaways are sent back to the Pondersoa resort and are offered any food their heart desires. Lyrsa requested steak and mashed potatoes but only ate a few bites of steak before feeling sick. She mentioned quite an adjustment period for her stomach and digestive system to get used to normal foods again.

After getting voted off the island, castaways are sent back to the Pondersoa resort and are offered any food their heart desires. Lyrsa requested steak and mashed potatoes but only ate a few bites of steak before feeling sick. She mentioned quite an adjustment period for her stomach and digestive system to get used to normal foods again.

We are so proud of Lyrsa and all she accomplished while representing Puerto Rico and the Gastronomy program as a castaway!

For more info on Lyrsa and her time on Survivor:

Restaurant Review: The Vermont Country Deli

Written by Ariana Gunderson, Edits by Sheryl Julian

If you’ve gone to southern Vermont to leaf peep, pick up lunch and then some at the Vermont Country Deli in Brattleboro. Inside the red barn you’ll find an expansive menu of prepared foods and made-to-order sandwiches, as well as a treasure trove of food souvenirs. The cozy scent of molasses cookies and the calls of order-taking fill the air. Jaunty baskets and worn copper pots hang from the ceiling, and the requisite array of maple products appear at every turn.

This self-consciously country country store has decorative gourds displayed on an antique wooden wagon, and red gingham curtains hung around the base of every wooden table. Hand-written chalkboard signs announce the specials and sandwiches of the day, along with the WiFi name and password. Warm lighting makes the room feel as cozy as a mug of the self-serve coffee poured in front of a brick bread oven. It’s a tourist’s dream with the feel of a local’s hub.

As soon as you walk in, you’ll be greeted by a heap of dinner-plate-sized cookies (they must be the source of the brown butter you’ve smelled from the parking lot). Before you reach the deli counter, you wend through displays of every imaginable maple product: cotton candy, pepper, popcorn, lip balm, fudge, and, of course, the syrup itself in jugs, jars, and cans.

The line for the deli counter snakes around the corner (which helpfully gives you a chance to peruse the small but intriguing cider, craft beer, and local wine selections) and nearly every customer in line orders Baked Cheddar Macaroni & Cheese. Follow their lead. Made with local Vermont cheddar and broiled in a two-foot diameter cast iron skillet, the mac & cheese is the signature dish, and it’s easy to believe the posted sign that in 2017, the shop sold 44,000 pounds of the stuff: “That’s 22 tons… Or, 6 Full Grown Elephants,” it reads. This classic comfort dish is satisfying with brightly sharp cheddar and a smoky, crunchy top from the broiler.

Prepared salads and ready-made side dishes also fill the deli case, ranging from burritos to a Super-Food Slaw, from samosas to tabouli salad. Some are made in-house and some are prepared by other local establishments, but the breadth of dishes ensures that all tasters have options.

The main attraction for the lunch crowd is the “Road Food” counter, with signature sandwiches named after area roadways. At what looks like a standard deli counter come sandwiches with local cheddar on house-baked bread (top pick: the sourdough) to make them superlative. If you pop in when the maple-barbecue pulled pork is on offer, don’t pass it up; it’s loaded with a sweet, cool slaw and, of course, local cheddar. The soft and smoky sweet BBQ is secured in a sturdy brioche bun and wrapped in satisfyingly thick butcher paper (for the brief moments you hold out until tearing into it, that is) and thoughtfully accompanied by a moist towelette. You won’t be able to resist taking home one of the eight fruit pies cooling on the countertop, or snagging a loaf of freshly-baked bread (either would be a sure bet for making friends at home).

These sandwiches, salads, cookies, and pies are best enjoyed beside the rushing Whetstone Brook along the shop’s patio, or as an ethereal picnic a few steps away at the Creamery Covered Bridge. It’s enough to make you forgive the endless maple displays.

436 Western Avenue, Brattleboro, VT 05301

802-257-9254

Open 7 Days a Week, 7:00am to 7:00pm

Restaurant Review: Rhythm ‘n Wraps

Written by Shannon Fitzgerald, Edits by Sheryl Julian

A brightly-colored chalkboard menu greets customers, boasting music and city-related adjectives to describe the food that awaits: phat, gangsta, ballpahk. At first glance, Rhythm ‘n Wraps, located near the Boston University West Campus, is unassuming. The tables are small squares with basic wood chairs, reminiscent of a cafeteria. Every eating surface has a painted mason chair--red, green, or yellow, the color scheme of the shop--with a single battery-operated tea light inside. Aesthetics, however, should not stop you from eating here. Fans of the original food truck, or anyone trying this restaurant for the first time, are in for a treat.

Rhythm ‘n Wraps began as a food truck in Cambridge in 2013. Five years later, they opened a storefront in Boston offering vegetarian food that is full of flavor and originality. Every item on the menu is meatless, with vegan options to replace dairy ingredients. Each ingredient and spice is chosen specifically for their mind-body elements, according to the restaurant’s website. It provides a breakdown of the specific health benefits provided, stemming from Chef Lee Roy Sim (also known as O'Shinga RamaShinga) and his interest in Ayuervedic cooking (based on the holistic medicine system often tied to yoga and spirituality).

Fueguito, a taco with refried beans, cheese, guacamole, tomato, sour cream, and lettuce, comes two per order. Each has two soft corn tortillas encasing the warm fillings. The double layer allows the taco to stay together--one would have been too flimsy and soggy—and a chipotle seasoning provides a cohesive flavor throughout every bite.

The Ballpahk wrap, is a white-flour tortilla containing sautéed peppers and onion, vegan Italian sausage made of soy protein, garlic aioli, and relish. The wrap comes with an open, unfolded top. Colorful vegetables peek out, creating an appetizing image. Red and yellow peppers play into the color palette of the restaurant, matching the mason jar lights. Warm and well-cooked, the garlic aioli enhances the sausage’s seasonings.

In addition to main dishes, Rhythm ‘n Wraps offers sides and beverages. Grilled Mack ‘n Cheese, unfortunately, does not live up to its name. Although savory and cheesy, grilled is a misnomer. Topped with baked bread crumbs, the elbow macaroni itself is not crispy, but buttery and oily. This side seems to miss the comfort-food mark with both its name and the restaurant’s theme of healthy foods.

To drink, Rhythm ‘n Wraps has a house-made beverage: a hibiscus-based punch. The Rhythm Punch is tangy and a vibrant shade of purple. It is smooth; no seeds, leaves, or sediment in sight. Ginger and hibiscus battle each other for dominance, creating a different primary taste with each sip. Bitterness, expected from the combination of hibiscus, ginger, and lime, lingers long after the drink is finished.

Healthy, vegetarian, and affordable--nothing is over $20--Rhythm ‘n Wraps should not be turned down based on its appearance. The extensive, savory menu provides options for all tastes and preferences. While no health benefits were immediately recognized upon consumption, the food is filling: a benefit of contentment that cannot be denied. You don’t have to be a yogi to enjoy Rhythm ‘n Wraps food.

Brick-and-mortar location for Rhythm ‘n Wraps is at 1096 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston MA, 02134. It operates 11am-9pm Monday-Thursday, 11am-11pm Friday-Saturday, and 11am-7pm Sunday. Information about the restaurant and the food truck schedule can be found on rhythmnwraps.com or by calling (857) 829-1090.

Nosh Box: a weekly food newsletter and podcast for while you’re eating

This post is guest-written by Jared Kaufman, a Gastronomy student who writes and hosts Nosh Box, a food newsletter and podcast.

Whenever I used to find myself needing to scarf down a quick meal — which still happens more often than I’d like, especially as a Gastronaut — I would wonder: What was I supposed to do while I was sitting there eating? It felt like too little time to get any serious productive work done, but also too much time to justify mindlessly scrolling through social media. (So, naturally, social media it was.)

Eventually, though, I started reading newsletters. I found that the size of stories fully contained within email newsletters was a great match for that mealtime block. But I couldn’t find a food newsletter specifically designed to read while I was eating. So in October 2017, I combined my food journalism background with my desire to get food stories in my inbox for my lunch break, and the result was Nosh Box, a weekly "eater’s digest."

Now in both newsletter and podcast form, Nosh Box explores a different brand, ingredient, dish, or food phenomenon every Tuesday, and I try to answer the question of what our food can tell us about ourselves. (While Nosh Box’s weekly food feature story is intentionally sized to read or listen to during meal times, you can also check it out while walking down the street, riding the T, going to the bathroom — I don’t judge!)

Over the past year, I’ve written over 150 issues of Nosh Box, about topics ranging from Cheetos to corn vs. flour tortillas to why chip bags are half-full of air. And I’m rolling out some new ideas, too. As I mentioned, I recently began releasing a thematically paired episode of the Nosh Box Podcast with each week’s email. Plus, my original idea for Nosh Box was as a meal-coordinated link roundup, so I recently brought that back in the form of a weekly segment called The Schmear, where we give you a taste of the food news and stories worth reading. And on the last Tuesday of every month, starting this week, the newsletter and podcast will be devoted to The Schmooze, an interview with someone cool in the world of food — a journalist, chef, researcher, author, eater.

As I’ve been thinking of ways to improve Nosh Box, I’m inspired by the people I’ve met and the concepts I’ve encountered in the Gastronomy program. For example, critical theory readings from the Sociology of Taste special topics course informed a recent edition of Nosh Box about the ways Ocean Spray (which is obligated to buy and resell all the cranberries its member growers produce — about two-thirds of the world’s supply) manufactured demand for an otherwise undesirable berry. And with the introduction of The Schmooze, I’m excited that some of the food-world luminaries I’ll get to talk to will be Gastronomy students, faculty, and alumni.

If you’re interested in getting Nosh Box in your inbox and podcast feed every Tuesday, you can subscribe at bit.ly/NoshBox. And if you have any ideas for topics I should explore or people I should talk to, shoot me an email at noshbox@jaredkaufman.com!

Considering Class & Potato Chips

You many not think about it as you crunch your way to the bottom of the bag, but potato chip packaging says a lot about social class. In this post, I'll tell you about how the Boston University Gastronomy Program got community members thinking about chips + class, and then share a how-to guide for doing this activity yourself.

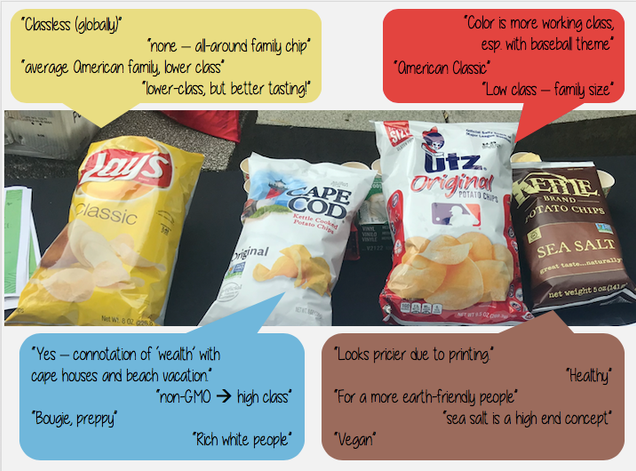

At a recent BU Farmer’s Market, the Gastronomy Program invited passersby to consider class on four potato chip bags (all flavored with only salt, for consistency’s sake): LAY’S, Cape Cod Potato Chips, Kettle Brand Potato Chips, and Utz.

To center this activity in embodied learning (thank you, Food and the Senses!), we began with a potato chip taste test. (This was also a good way to attract people to our table.)

“Can you identify this potato chip?” we called to people passing through the market. “Test your potato chip knowledge!” we challenged them.

Those interested in participating were handed a blind sample of one of the chips in a Dixie cup, and invited to guess which bag it had come from. Most participants were able to eliminate two brands right away, ascribing LAY’S and Utz to one group, and Kettle and Cape Cod to another. The majority of tasters correctly identified at least one chip, and we rewarded them with BU Gastronomy-branded reusable straws.

Once we had gotten participants interested in our table and engaging with the potato chips, we encouraged them to take a closer look at the packaging in an activity adapted from Potter Palmer’s Food and Visual Culture class.

Could they identify markers of social- or socio-economic class on the potato chip packaging? Does the material or visual imagery of the bag itself convey an idea of a particular class or indicate a particular target customer?

The overwhelming response was: YES! Here is a collection of responses we gathered from participants at the Farmer’s Market in Marsh Plaza on October 4th:

Utz Brand Potato Chips:

A lesser-known chip in this activity (it was a very regional brand until recently), Utz was nevertheless readily identified as a lower-class chip due to its heavy baseball imagery and large bag made of thin, shiny plastic. This brand was also perceived as more patriotic as it was printed in red, white, and blue.

LAY’s

Participants were often stumped to find class markers on the Lay’s chip bag. Because the brand is so popular globally and was the most widely consumed chip in our participants’ daily lives, some tasters described it as ‘class-less.’

Others found a connection to the icon of the ‘typical’ American family. When considering the LAY’S bag (as with Utz), participants expressed a belief that the ‘average American’ is lower class. (It’s interesting and important to remember that this particular tasting took place at farmer’s market with many organic produce vendors on a University campus.)

Cape Cod Potato Chips

The Boston location of this tasting meant that many of our tasters had vivid ideas and associations for Cape Cod. A beach vacation destination populated by second homes of the Boston suburban elite, Cape Cod was considered unequivocally upper class by our tasters. These upper-class associations with the nearby peninsula were reinforced by the “Non-GMO” labeling on the bag, which participants picked up on.

Kettle Brand Potato Chips

When invited to consider the packaging of the Kettle brand potato chips, tasters translated high-class markers like “non-GMO” labeling into adjacent values not literally printed on the bag, including where they would expect to buy the chips (Whole Foods) and a variety alternative food movement causes.

Now it's your turn!

Want to host your own potato chips + class activity? Here's a how-to guide, promotional poster, and response sheet to use or adapt for your own event. Be sure to let us know how it goes!

Ariana Gunderson is a Master’s student in the Gastronomy Program, studying food memory and writing on arianagunderson.com.

Photo Credits: Barbara Rotger and Ariana Gunderson

Spring 2019 Course Spotlights

Today we'd like to highlight some of the unique electives we'll be offering in the upcoming spring semester. Read on to see what's available!

The Science of Food and Cooking

MET ML 619 | Tuesdays 6-8:45 | Valerie Ryan

Cooking is chemistry, and it is the chemistry of food that determines the outcome of culinary undertakings. In this course, basic chemical properties of food are explored in the context of modern and traditional cooking techniques. The impact of molecular changes resulting from preparation, cooking, and storage is the focus of academic inquiry. Illustrative, culturally specific culinary techniques are explored through the lens of food science and the food processing industry. Examination of "chemistry-in- the-pan" and sensory analysis techniques will be the focus of hands-on in- class and assigned cooking labs.

Reading and Writing the Food Memoir

MET ML 615 | Mondays 6-8:45 | Dr. Karen Pepper

Course involves critical reading and writing and examines the food memoir as a literary genre. Students gain familiarity with food memoir, both historical and current; learn how memoir differs from other writing about food and from autobiography; learn to attend to style and voice; consider the use writers make of memory; consider how the personal (story) evokes the larger culture.

Wild and Foraged Foods

MET ML 625 | Thursdays 6-8:45 | Netta Davis

Humans have been foraging for food since prehistoric times, but the recent interest in wild and foraged foods raises interesting issues about our connection to nature amid the panorama of industrially oriented food systems. From political economy to Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), this course explores how we interact with, perceive, and know our world through the procurement of food. Students take part in foraging activities and hands-on culinary labs in order to engage the senses in thinking about the connections between humans, food, and the environment.

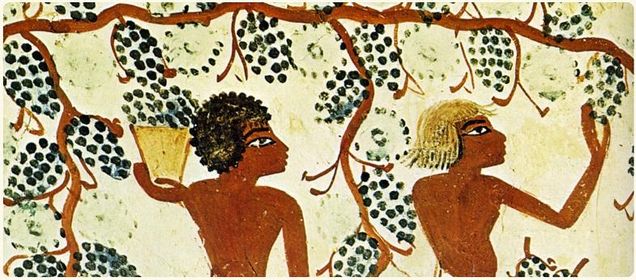

History of Wine

MET ML 632 | Online Course | Sandy Block

In this course we explore the long and complex role wine has played in the history of human civilization. We survey significant developments in the production, distribution, consumption and cultural uses of grape-based alcoholic beverages in the West. We study the economic impact of wine production and consumption from the ancient Near East through the Roman Empire, Europe in the Middle Ages and especially wine's significance in the modern and contemporary world. Particular focus is on wine as a religious symbol, a symbol of status, an object of trade and a consumer beverage in the last few hundred years.

Culture and Cuisine of Italy

MET ML 636 | Blended Class | Mary Ann Esposito

There is no such thing as Italian food. This statement is confirmed by the uniqueness and locality of the foods of Italy. This course will introduce students to regional Italian foods, taking into account geography, historical factors, social mores and language. There will be an emphasis on identifying key food ingredients of northern, central, and southern regions, and how they define these regions and are utilized in classic recipes. In addition, the goal will be to differentiate the various regional cooking styles like casalinga cooking versus alta cucina cooking.

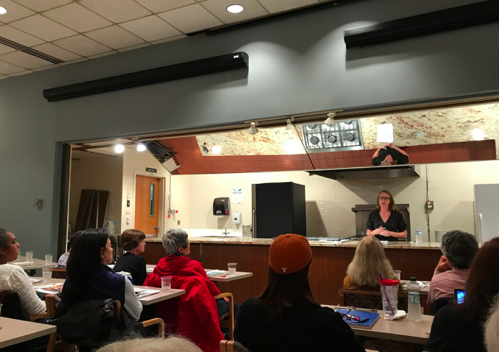

A Discussion of Edna Lewis with Dr. Sara Franklin

The food and words of Edna Lewis provoke “a church experience,” asserted Dr. Sara B. Franklin in last night’s Jacques Pépin Lecture on her new edited volume Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original. This collection of essays, including a contribution from Gastronomy Program Director, Dr. Megan Elias, explores the life and impact of the great Southern chef.

Franklin opened her lecture by reading an excerpt of Lewis’ essay, “What is Southern?,” discovered and published posthumously in 2008. She described her own near-sacred experience of encountering this essay in Gourmet magazine, becoming enamored with Lewis as a writer, and immediately cracking open her seminal cookbooks.

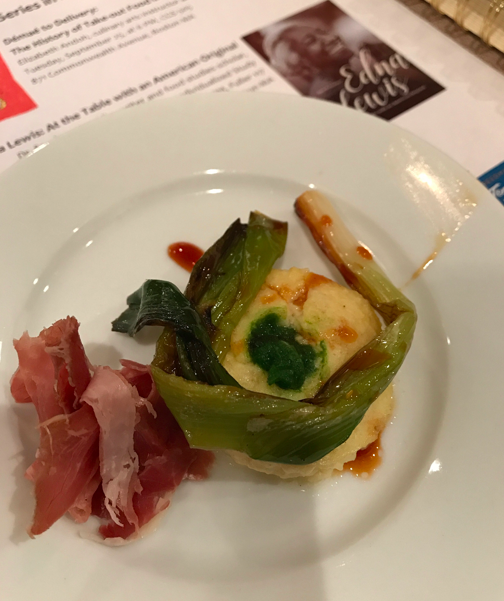

Others shared their knowledge of and experience with Edna Lewis as chef Barry Maiden’s tastes of Edna Lewis’ spoonbread, skillet scallions, and country ham made their way to lecture attendees. One guest spoke with awe of having visited Lewis’ restaurant in Brooklyn, and having even met the chef when she came into the dining room.

Lewis’ essay “What is Southern?” was published the same year Chef Barry Maiden opened his James Beard Award-winning restaurant, Hungry Mother. The essay served as inspiration to Maiden, a fellow Virginian, as did Lewis’ cookbooks; he described The Gift of Southern Cooking as a bible at Hungry Mother.

In her lecture, Franklin argued that Edna Lewis wrote cookbooks that were subtly and unmistakably political. With recipes for Emancipation Day but not the 4th of July, Lewis insisted on an honest accounting of American history, and demanded the visibility of blackness in Southern cooking.

This volume on Lewis is likewise politically contextualized; after the shooting in Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, Franklin chose to pursue this book as a political response. Franklin positioned this book as a disruption of the pattern of “overlooking food stories, women’s stories, and black stories.” A thoughtful and timely collection of essays on the life and work of a founding figure of Southern cuisine, this book appropriately asserts the importance of Edna Lewis to the history and present experience of American food.

Ariana Gunderson is a Master’s student in the Gastronomy Program, studying food memory and writing on arianagunderson.com.

Photo Credit: Jared Kaufman

GRLSQUASH: A women’s food, culture, and art journal

My name is Madison Trapkin and in April I founded GRSLQUASH, a women’s food, culture, and art journal.

I started a food and art blog while I was still in college. This was my first real foray into food writing outside of an academic setting. I created an interdisciplinary food experience on this blog using a combination of writing, photography, music, recipes, and more. This was only the beginning. Last year I moved from my hometown of Atlanta, GA to Boston for grad school just in time for the season’s first snowstorm. A few weeks later, I walked into the first of many classes in the Gastronomy Program, Karen Metheny’s Anthropology of Food course. Still, this was the beginning.

I built up my portfolio (and my courage) during my first year in the grad school. I felt inspired by fellow classmates who were really kicking ass in their fields — everything from a CBD-based ice cream startup to pastry chefdom at a swanky Las Vegas hotel. I pitched my first story, a pseudo-restaurant review for the Boston Globe, while sitting in one of my classes last summer. And they actually liked it! I pretty much pitched at least one story a week from that point on, with varying success. To date I’ve had a few pieces published, but more importantly I’ve had LOTS of pieces turned down. This spring, in Laura Ziman’s Food in Art course, I was listening to an especially inspiring guest lecturer when I received yet another rejection email from a publication I’d pitched to. This was it. The lecturer, a local artist named Anna Stabler, encouraged us to build an army of talented people to surround us and to just….do it — sort of a build-it-and-they-will-come mentality. So, I did.

I rushed home from class to jump and yell excitedly to my now-fiancé about the idea I’d had. I would start my own publication, one that focused on all the things I loved most: food, art, and culture. This was also the beginning. The beginning of GRLSQUASH.

The Gastronomy program has empowered me as a writer and reinforced the importance of intersectionality in everything. It also facilitated my relationships with the majority of the GRLSQUASH Board! Besides my co-founder, Jess Graham, all other Board members are current or past members of the Gastronomy Program: Laurel Greenfield, Sam Dolph, and Rachel DeSimone.

Since starting GRLSQUASH it has grown immensely. A journey that began as a way to publish and promote underrepresented voices in the food and art worlds has evolved into a community-building venture, complete with collaborations involving some really incredible like-minded Boston organizations and spaces (Practice Space, Hourglass, The Cauldron, Angry Asian Girls, + more!). I’m thrilled about our growth and excited for our future.

Our second issue, themed: SELF, is currently in the works with an open call for submissions from now til Octber 12th! We recently launched our collaborative Calendar where you can find upcoming GRLSQUASH events + exciting happenings from many organizations and spaces within the GRLSQUASH community. And if you haven’t already, you can still order ISSUE ONE: MOTHERS/FOREMOTHERS!

Website: https://www.grlsquash.com

Submissions: https://www.grlsquash.com/submit

IG: @grlsquash

Calendar: https://www.grlsquash.com/calendar/

New students for fall 2018, part 4

We look forward to welcoming new students in the MLA in Gastronomy and Food Studies Graduate Certificate programs this fall. Get to know a few of them here.

Jared Kaufman grew up around Minneapolis, Minnesota, and has always  had an interest in food — when he was 5, his career aspiration was to be a cake decorator; he once dressed up as Emeril Lagasse for Halloween; and in high school, he hosted a food-reviewing YouTube channel that’s now deeply embarrassing to him.

had an interest in food — when he was 5, his career aspiration was to be a cake decorator; he once dressed up as Emeril Lagasse for Halloween; and in high school, he hosted a food-reviewing YouTube channel that’s now deeply embarrassing to him.

After earning a journalism degree from the University of Missouri in 2018, he now works as a freelance food writer and writes a twice-weekly food newsletter called Nosh Box. He's interested in how social factors and government policy intersect with — and sometimes clash with — our food culture, and what that crossroads can illuminate about which foods we choose to (or are able to) put on our tables. Jared hopes to bring together the knowledge he gains in the Gastronomy program with his journalism background for a career as a food policy, systems, and culture reporter. He also eats a bagel nearly every morning for breakfast, and should’ve stopped himself before telling you he has a bagel pillow on his bed and a bagel sticker on his water bottle.

Lauren Allen was born and raised in Austin, Texas. Though she spent part of her childhood in Saudi  Arabia, she ended up back in Austin at the age of eight. She graduated from the University of Texas with a major in Geography and Religious Studies, and a minor in Philosophy. Shortly after graduating, she took a kitchen position at a restaurant where she was hosting and now has seven years’ experience working as a line cook and chef. In 2013 she traveled in Ireland, volunteering on organic farms and working in kitchens. Inspired by this “farm to table” style cooking, she returned home and started her own pop up dinner series under the name Cloak & Dagger, with menus focusing on local and sustainable ingredients. Cloak & Dagger has been successfully running for the past five years in backyards, out of food trailers, and in various bars/restaurants across Austin. She has experience cooking with insects, but especially loves butchering and charcuterie. She has always had a passion for writing and traveling, and wishes to tie those in with her passion and excitement for food and gastronomy.

Arabia, she ended up back in Austin at the age of eight. She graduated from the University of Texas with a major in Geography and Religious Studies, and a minor in Philosophy. Shortly after graduating, she took a kitchen position at a restaurant where she was hosting and now has seven years’ experience working as a line cook and chef. In 2013 she traveled in Ireland, volunteering on organic farms and working in kitchens. Inspired by this “farm to table” style cooking, she returned home and started her own pop up dinner series under the name Cloak & Dagger, with menus focusing on local and sustainable ingredients. Cloak & Dagger has been successfully running for the past five years in backyards, out of food trailers, and in various bars/restaurants across Austin. She has experience cooking with insects, but especially loves butchering and charcuterie. She has always had a passion for writing and traveling, and wishes to tie those in with her passion and excitement for food and gastronomy.

Payal Parikh, or Pie, as she tends to goes by is new to Boston. She grew up by the beach in South  Jersey where she helped her parents in the kitchen cooking traditional Gujarati Indian foods as well as regionalized New Jersey favorites. Each summer she did what all the local teens did and worked jobs at the beach, Pie always gravitated to food-centric positions. Whether it was working at a restaurant on the marina, a bakery on the boardwalk or a water ice stand, they all played their part as to where she is today. When asked about her nickname (and clarifying the spelling) she is often asked what her favorite type is, she always answers the same – pizza, preferring the savory to sweet.

Jersey where she helped her parents in the kitchen cooking traditional Gujarati Indian foods as well as regionalized New Jersey favorites. Each summer she did what all the local teens did and worked jobs at the beach, Pie always gravitated to food-centric positions. Whether it was working at a restaurant on the marina, a bakery on the boardwalk or a water ice stand, they all played their part as to where she is today. When asked about her nickname (and clarifying the spelling) she is often asked what her favorite type is, she always answers the same – pizza, preferring the savory to sweet.

For her undergraduate studies she attended Villanova University, located outside of Philadelphia, where she earned her B.S. in Business Administration and majored in Management and minored in Marketing and Entrepreneurship. She then spent her next 13 years as an account manager in the telecom industry learning the ins and outs of Fortune 500 companies.

Living in the vibrant food scene of Philadelphia reinvigorated her passion for the culinary arts and food studies. She began researching as many new restaurants and bars in Philadelphia and through her extensive travels as possible when she realized so much could be replicated in her own home and that cooking is a form of traveling. She began hosting dinner parties for her friends and family in her apartment, which was the stepping stone she needed to realize she wanted a career she was passionate about which led her to set forth on applying for her MLA in Gastronomy at BU. She is looking to bridge her business background, love of travel, and passion for food through the program.

Currently, Pie is working at Harpoon Brewery baking delicious pretzels, customizing sauces from scratch and learning about the brewing industry. In her free time, she enjoys cooking, traveling, listening to live music and golf.

New students for fall, part 3

We look forward to welcoming new students in the MLA in Gastronomy and Food Studies Graduate Certificate programs this fall. Get to know a few of them here.

Tanya Bouldin is Virginia native who has been in Boston for 4.5 years. In her 20’s she worked in the bar and restaurant business but moved into technology when the .com boom was happening. She had a very successful 18-year career in technology which led her to Boston via a job transfer.

Over the past 20 years Tanya's love of cooking, food and travel have blossomed. She writes: "I have had many opportunities to experience the culture of food and people by living in numerous states (GA, LA, FL, MO, &CA) and traveling to the EU and Central America. My passion for food isn’t limited to a particular region or arena. I have a natural curiosity for all types of cuisine and am always in search of a perfect bite. I even went so far as to go to Noma in Copenhagen just to have dinner before they closed the flagship location…what an amazing experience. As much as I enjoy dining out and finding great spots, I feel the most pleasure in cooking with/for friends and family. I truly feel that we can make deep connections rooted in food and the cultures that surround it. In August of 2017 I completed my BS in Information Technology and Project Management but didn’t feel the level of engagement that I once had in that industry. After much introspection, I made the decision to leave that career and ‘jump’ back into the culinary world. It feels like a natural progression to the next phase of my life. My immediate goal is to learn traditional techniques and explore the various aspects of culinary and it’s ever growing importance in our global world. Entering the MLA Gastronomy program is going to be an exciting challenge and I can’t wait to begin!"

Over the past 20 years Tanya's love of cooking, food and travel have blossomed. She writes: "I have had many opportunities to experience the culture of food and people by living in numerous states (GA, LA, FL, MO, &CA) and traveling to the EU and Central America. My passion for food isn’t limited to a particular region or arena. I have a natural curiosity for all types of cuisine and am always in search of a perfect bite. I even went so far as to go to Noma in Copenhagen just to have dinner before they closed the flagship location…what an amazing experience. As much as I enjoy dining out and finding great spots, I feel the most pleasure in cooking with/for friends and family. I truly feel that we can make deep connections rooted in food and the cultures that surround it. In August of 2017 I completed my BS in Information Technology and Project Management but didn’t feel the level of engagement that I once had in that industry. After much introspection, I made the decision to leave that career and ‘jump’ back into the culinary world. It feels like a natural progression to the next phase of my life. My immediate goal is to learn traditional techniques and explore the various aspects of culinary and it’s ever growing importance in our global world. Entering the MLA Gastronomy program is going to be an exciting challenge and I can’t wait to begin!"

James Lysons hails from the Pacific Northwest but has worked as a chef in all corners of the country. James grew up in a family where food was a focal point. He has fond memories of standing on a step stool learning the art of cooking an omelet from his mother (who is also an accomplish cook). James began working in kitchens at the age of 16, starting after school as a dishwasher and eventually making his way to prep cook, cook and so on. He received his Bachelors from New England Culinary Institute and has been fortunate enough to work at some great restaurants like Gramercy Tavern in New York, Trio in Chicago and Auberge du Soleil in Napa.

Northwest but has worked as a chef in all corners of the country. James grew up in a family where food was a focal point. He has fond memories of standing on a step stool learning the art of cooking an omelet from his mother (who is also an accomplish cook). James began working in kitchens at the age of 16, starting after school as a dishwasher and eventually making his way to prep cook, cook and so on. He received his Bachelors from New England Culinary Institute and has been fortunate enough to work at some great restaurants like Gramercy Tavern in New York, Trio in Chicago and Auberge du Soleil in Napa.

With the changing climate in the food world, James has been inspired to take his experience and knowledge from the kitchen and dedicate himself to educating fellow chefs about the importance of sustainable cooking. James believes that through education, lobbying, and inspiration, the trend of wild ingredients disappearing can be reversed. James is excited to take part in the gastronomy program and believes it will elevate his abilities to advocate for preservation and restoration of the world's amazing ingredients.

Wiley McCarthy grew up in New Orleans and Georgia before migrating to  Massachusetts for high school, college, marriage, and raising children. After graduating from Harvard in 1983 with a degree in History with Economics, she worked as a textbook editor at Houghton Mifflin, then turned to freelance work with the birth of her first child. After a long absence from work and school but with a long history of baking and food interests, she began volunteering for organizations targeting food as medicine, food rescue, and charitable food distribution. With additional interests in food policy, nutrition, and eating disorders (not to mention just plain eating), the Gastronomy program seemed a natural path to pursuing some of those interests on a professional level.

Massachusetts for high school, college, marriage, and raising children. After graduating from Harvard in 1983 with a degree in History with Economics, she worked as a textbook editor at Houghton Mifflin, then turned to freelance work with the birth of her first child. After a long absence from work and school but with a long history of baking and food interests, she began volunteering for organizations targeting food as medicine, food rescue, and charitable food distribution. With additional interests in food policy, nutrition, and eating disorders (not to mention just plain eating), the Gastronomy program seemed a natural path to pursuing some of those interests on a professional level.