Home

The Importance of Self-Care for Law Enforcement Officers

Matthew S. Paradis

It is no secret that law enforcement officers are repeatedly exposed to stress and trauma throughout their careers. The cumulative stress and/or PTSD can wreak havoc on the overall health of an officer, especially if left unmanaged. Police officers generally experience higher rates of depression, PTSD, burnout, and anxiety when compared to the general population (NAMI). They also commit suicide 54% more than the general population (Violanti, 2020). This number is exacerbated when considering small departments, as this rate increases to over three times the national average” (NAMI).

There are many contributing factors to these statistics and yet despite knowing the statistics, the underlying problems persist. Police officers are tasked with solving or addressing many societal problems and yet they are hesitant to address their own. Barriers exist that discourage or prevent officers from seeking out help, even if they recognize that they are having difficulties with PTSD or some form of mental illness. More importantly, there is a stigma surrounding officers and emotional and/or psychiatric conditions, such as fear of losing their job, having their ability to carry a firearm taken away, reassignment to a less “stressful” position, and being labeled as weak and eliciting ridicule, humiliation, and retaliation from fellow officers or administration (Rousseau, Module 6).

In light of the ominous statistics previously discussed, there are viable options to help address the underlying issues at hand, mainly in the form of self-care. While officers are hesitant to seek assistance, exercising various forms of self-care can be incredibly beneficial to an officer’s overall health and well-being. Simplistically, officers should do their best to get adequate sleep, exercise regularly, eat well, do their best to relax, and connect with those who they have meaningful relationships with, particularly significant others. These areas need to be prioritized by officers who wish to continue to enjoy their lives and their careers rather than just going through the motions. These things must be done with purpose and in doing so, officers may find themselves in a better position to serve others to the best of their ability.

When the oxygen masks come down in an airplane during an in-flight emergency, flight attendants advised passengers to take care of themselves first before taking care of others. This same principle holds true with police officers prioritizing their own health (Cordico). Whether it be yoga or some other type of physical exercise, practicing mindfulness, journaling, finding a hobby, speaking with a mental health professional or peer support, or some combination of these strategies or others, police officers need to champion their own health and in doing so, they will be better suited and equipped to effective manage what the job will throw at them and be in a position to serve their families and communities to their best of their abilities. Self-care can provide a sense of personal control in an otherwise chaotic world, allowing us to pursue meaningful endeavors and engage in healthy lifestyle choices, supporting personal growth and furthering our resilience to the stress and trauma inherent in policing (Rousseau, Module 1).

Greco, N. (2022, March 4). The importance of self-care for law enforcement. Cordico. https://www.cordico.com/2021/05/21/take-care-of-yourself-why-law-enforcement-officers-need-self-care/

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2023). Law enforcement. NAMI. https://www.nami.org/Advocacy/Crisis-Intervention/Law-Enforcement

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 1 - Introduction to Trauma. MET CJ720. Boston University.

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 6 – Trauma and the Criminal Justice System. MET CJ720. Boston University.

Violanti JM, Steege A. Law enforcement worker suicide: an updated national assessment. Policing. 2021;44(1):18-31. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2019-0157. Epub 2020 Oct 21. PMID: 33883970; PMCID: PMC8056254.

Can Playing Dungeons & Dragons Be a Trauma Treatment Tool That Bridges the Victim-Offender Overlap?

It’s close to midnight when your party enters the roadside inn half a mile outside of the town of Waterdeep. You’re a rogue and thief wanted for murder, so you conceal your face. While your friends make their way over to the bar, you slink into a booth in the darkest corner of the dining room. As you note all the possible exits in the building, a waitress meets your gaze and begins to make her way over to where you are sitting. Before she can get close, two strangers block her path and start speaking to her in hushed but insistent tones. You succeed in rolling a perception check. The waitress seems extremely distressed, and you hear her say, “I said ‘no,’ now leave me alone.”

You’re a rogue and a thief. It would be best if you didn’t make a scene, but your character sheet also says that part of your background is that your family abused you, and you vowed never to let an innocent person be hurt by someone else. Your friends are distracted at the bar and don’t see the woman who needs help. It’s up to you. You roll a successful intimidation check and put a hand on the shoulder of one of the aggressors. “She asked you to leave,” you say. Thankfully, the strangers leave the inn, only looking a little annoyed. “Thank you,” the waitress says, stopping short when she sees you more clearly. Recognition flashes across her face. “It’s you!” Well, here it comes, you think. Off to jail, again. “Everyone, everyone!” she says, “It’s The Savior of Baldur’s Gate! Get this hero a drink!!” Oh yeah, you remember, I guess we did save that city a few sessions ago. Word travels fast.

~

In the first discussion post for this course, I was instantly drawn to van der Kolk’s (2015, p. 17) observation about imagination: “Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives [and] it is the essential launchpad for making our hopes come true.” From victims of child abuse using sand to play and act out narratives that they may not remember the words for (Rousseau, 2023b, p. 16) to veterans of war struggling to see peaceful images in inkblots (van der Kolk, 2015, p.16) to offenders of horrific crimes having to live with the trauma of institutionalization on top of learning to live a crime-free life (Rousseau, 2023c, p. 15), imagination is the most essential tool to build resilience in environments where inspiration is in short supply.

While the story I wrote above might seem goofy to you as the reader, I believe that as the player, and as your own main character, the choices you make and the actions you take can be exhilarating, and important at the very least. This is why I think we love knowing a little bit about our star sign, and why we take all those surveys that tell us which character of whatever TV show we would be. This can be a fun reverie for anyone, if, of course, your horoscope says you’re going to win the lottery and you’re most like the protagonist, hot girl, cool guy, etc. For people who may avoid their past or find that they are unable to leave their past behind them, I believe games, like trauma-informed Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), can be used to practice imagination, act as a complex form of talk, group, and exposure therapy, and instill a long-lasting resilience in people who have experienced many different forms of trauma and chronic stress.

If you’re unfamiliar with D&D, this is a great synopsis of the game, written by Blakinger (2023), who interviewed inmates on death row who used the game to cope with their death sentences: “[D&D is a] tabletop role-playing game known for its miniature figurines and 20-sided dice. It combines a choose-your-own-adventure structure with group performance[.] Participants create their own characters — often magical creatures like elves and wizards — to go on quests in fantasy worlds. A narrator and referee, known as the Dungeon Master, guides players through each twist and turn of the plot [with] an element of chance.”

Before you discount me completely, remember that playing games that improve our “physical, mental, emotional, and social resilience” can add years to our lives (McGonigal, 2012; Rousseau, 2023a, p. 8) and individuals who have experienced trauma and chronic stress may already have had the physical effects of stress take years off their life (Rousseau, 2023a, p. 4). Rousseau (2023a, p. 4) lists “uncertainty, loss of control, and a lack of information” as factors that trigger stress. It is unrealistic to imagine a future in which none of these factors occur, but the human body’s response to stress (van der Kolk, 2015) calls for treatment in safe spaces where we can learn how to deal with this natural response to past trauma. With every roll of the dice, the success of your decisions in this game is left completely to chance, but the player is always in control of what they decide to do and how they respond to successes and failures. While there is a lack of information, the Dungeon Master knows everything about this fantasy world. There are boundless opportunities to learn, explore, and discover the unknown.

In addition to the safe space that this game creates as a practice zone to cope with stress and possibly even face one’s fears, I believe that D&D can also be used as a tool for reclaiming positive narratives and labels, particularly for offenders. Labeling theory states that “people become stabilized in criminal roles when they are labeled as criminals” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 7). A tool known as “redemption scripts” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 248-250) has been used in efforts for people to discover their “true selves” or the best parts of them that could be the foundation for a crime-free life. I believe with guidance from a therapist or other trained mental health professional, the character creation portion of this game, which often takes place one-on-one and before the roleplaying part of the game, could be beneficial to offenders seeking a personal label change.

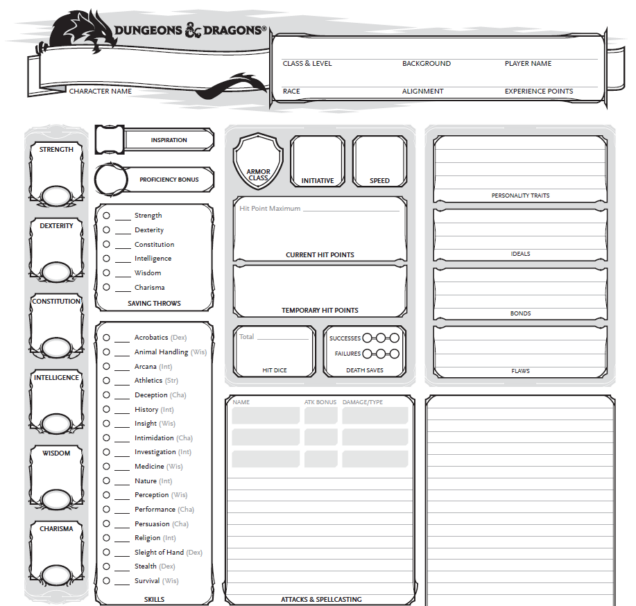

While this is just a brief exploration of this idea, it would be very interesting to see how resilient trauma-impacted individuals both inside and outside of prisons were after just a few sessions of playing D&D, and if they thought about their fantasy adventures outside of the sessions at all, and in what way. If you’ve never played D&D, I understand it might be confusing to think about how powerful this game can be. But, before you go, please look at the picture below. This is a D&D character sheet. It’s what you fill out for the character you play during the game. This is where you list your character’s strengths, weaknesses, background, personality, and if you’re inherently good, bad, or just straight chaotic. If you have a moment, read the categories on the sheet, and think about two things: 1. What would this sheet look like if I were the character in the story? Particularly, what would the four categories on the righthand column say? And 2. If I could be anyone, my true self, what would it say then?

Thank you very much for keeping an open mind, maybe learning more about something new, and considering my perspective!

(D&D Blank Character Sheet, 2023).

References

Blakinger, K. (2023, August 31). When Wizards and Orcs Came to Death Row. The Marshall Project. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/08/31/dungeons-and-dragons-texas-death-row-tdcj

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2022). Criminological theory: Past to present (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

D&D Blank Character Sheet [PDF]. (2023). Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://dnd.wizards.com/resources/character-sheets

McGonigal, J. (2012, June). The game that can give you 10 extra years of life. TEDGlobal 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_the_game_that_can_give_you_10_extra_years_of_life

Rousseau, D. (2023a). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 1. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023b). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 2. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023c). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 6. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, And Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Student Athletes & Self-Care

For my blog post, I want to focus on self-care tactics specific to student athletes. While we've explored the topic of self-care more broadly in this course (with specific emphasis on criminal justice professionals), being a full-time college student, I want to explore the burden on student athletes as that is a much closer population group to me and my friends. Self-care for student athletes is crucial for maintaining physical, mental, and emotional well-being while managing the demands of both academics and sports.

While speaking to my friends, they highlighted a few self-care strategies they implement in their own lives. Among these strategies is ensuring proper nutrition for peak athletic performance. They note that athletes should focus on a well-rounded diet that includes carbohydrates, proteins, healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals. When available, meal planning and consulting with a school-appointed nutritionist can help ensure they get the right balance they need. Additionally, another recurring theme in my conversations with the college athletes was the need for adequate rest and sleep. Quality sleep is vital for recovery and overall health. The Children’s Hospital of Colorado notes that athletes should aim for 9-10 hours of continuous sleep per night to support muscle repair, mental focus, and overall well-being (Children’s Hospital Colorado).

However, in my exploration of this topic, the athletes I spoke to noted several barriers to maintaining good mental health. These barriers included time constraints due to busy schedules, lack of support regarding their social lives, and limited access to healthy food. In my additional research, I found this was a recurring theme in regards to the self-care of student athletes more generally. One such study I found noted that collegiate athletes often feel pressure to prioritize their athletic performance over their health, which could lead to neglect of important self-care practices (Rensburg, 2014). Another study found that the student-athletes who asked for mental-health support experienced stigma surrounding mental health issues in more ways than one, including a lack of understanding and/or support from coaches and teammates, and a general perception that seeking help for mental health issues was a sign of weakness. Many participants reported feeling pressure to hide or ignore their struggles with mental health, which often worsened their symptoms and made them feel isolated. However, when student-athletes did receive the support and understanding needed, they reported feeling empowered and more willing to seek help in the future (Marques & Martins, 2018).

Moving forward, I would love to see a world where the fullness of student athletes' mental well-being is considered. Similar to the issues faced by criminal justice professionals, for student athletes to perform at the highest level they are capable of, they need intensive support systems and strong self-care strategies. In the future, I hope this includes strategies not only to strengthen them as athletes and students but also as people.

References

Children’s Hospital Colorado. (n.d.). How Does Sleep Impact Athletic Performance?. Sleep for Student Athletes. https://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions-and-advice/sports-articles/sports-safety/sleep-student-athletes-performance/#:~:text=Nine%20to%2010%20hours%20of%20continuous%20sleep%20helps%20with%20muscle,split%2Dsecond%20decision%2Dmaking.

Marques, L., & Martins, O. (2018). Scholarworks.edu. Exploring Mental Health Needs of Student Athletes. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/rr172364v

Rensburg, C. (2014). Researchgate.net. Exploring wellness practices and barriers: A qualitative study of university student-athletes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272458815_Exploring_wellness_practices_and_barriers_A_qualitative_study_of_university_student-athletes

Navigating the Healing Path: Unveiling the Intricacies of Trauma

In the realm of understanding trauma, Bessel Van Der Kolk's groundbreaking work in "The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma" has become a guiding light for those seeking to fathom the profound complexities of trauma and its impact on the human experience. As we delve into Part Three: The Mind's of Children, this insightful masterpiece, the journey into the interconnected realms of brain, mind, and body unveils a roadmap for healing that challenges traditional perspectives.

The Importance of Brain Development:

Van Der Kolk's emphasis on the interconnectedness of the brain, mind, and body prompts a deeper exploration into the significance of brain development, as highlighted in our course readings. Neuroscience continues to unravel the mysteries of the brain, shedding light on the profound impact of trauma. The illustration on page 53 intricately details the interplay between brain regions, particularly emphasizing the pivotal role of the prefrontal cortex, aptly referred to as the timekeeper (Van Der Kolk, 2014). "The more neuroscience discovers about the brain, the more we begin to understand the impact of trauma,"(Dr. Rousseau, 2023). The prefrontal cortex, crucial for normal human development, acts as the guardian of emotional regulation, fear comprehension, and the delicate balance between hyperarousal and hypoarousal. Van Der Kolk's insights invite us to contemplate the implications of early trauma on the development of this critical brain region.

Early Trauma and the Prefrontal Cortex:

In a healthy individual, the prefrontal cortex matures fully around the age of 25, making adolescence a period of developing maturity and turbulence. However, severe trauma during formative years can disrupt this process, leading to a smaller volume or developmental issues within the prefrontal cortex (Van Der Kolk, 2014). This disruption manifests as hypersensitivity to stressors, an impaired ability to self-regulate emotions, and heightened levels of fear and anxiety. "Individuals who have experienced severe trauma may have a smaller volume of or developmental issues with the prefrontal cortex," (Dr. Rousseau, 2023). The consequences are profound. Trauma victims often find themselves in a perpetual "stress" mode, where the oldest part of the brain reacts, shutting off conscious thought and triggering instinctual responses of fight, flight, freeze, or hide. Understanding this physiological response is crucial in comprehending the challenges trauma survivors face in their journey toward healing.

Stages of Adolescent Development and Trauma:

Normal human development follows a systematic progression, with each stage building upon the last. However, trauma introduces disruptive elements, impacting factors vital for healthy development. Van Der Kolk's work encourages a nuanced exploration of the stages of adolescent development and how trauma can impede these processes. Trauma disrupts the expected sequence of milestones, creating a tumultuous environment that challenges the very foundations of growth "as it relates to child development, can take the form of very disruptive and often problematic harm," (Dr. Rousseau, 2023). For an example an infant must first learn to sit, then crawl, and finally walk, with each stage building essential skills for the next. However, trauma can skew this sequence, leading to delays or deviations in the expected progression. This misalignment has cascading effects on cognitive, emotional, and social development, hindering the acquisition of crucial skills necessary for navigating the complexities of adult life.

Understanding the intricate interplay between trauma and adolescent development is paramount for effective intervention strategies. Van Der Kolk's insights underscore the need for a holistic approach that addresses not only the immediate consequences of trauma but also the long-term implications on an individual's developmental trajectory. By recognizing the ways in which trauma disrupts the natural order of growth, we can tailor therapeutic interventions to foster resilience, restore developmental pathways, and empower survivors to reclaim agency over their narrative. In doing so, we inch closer to a trauma-informed paradigm that recognizes the unique challenges faced by individuals navigating the delicate terrain of adolescence in the aftermath of trauma.

As we navigate the intricate landscape of trauma with Bessel Van Der Kolk, the importance of understanding brain development, especially the role of the prefrontal cortex, becomes evident. Integrating these insights into our discourse on trauma allows for a more comprehensive and compassionate approach to healing. Van Der Kolk's work not only challenges our existing paradigms but also urges us to reevaluate and innovate in our quest to support survivors on their journey towards recovery.

References:

Rousseau, D. (2023). Trauma and Crisis Intervention. Module 2. Childhood Trauma. Metropolitan College Boston University.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Haitian Resilience, Natural Disasters & COVID-19

During the course, I read a piece by Guerda Nicolas about Haitians coping with the traumas associated with natural disasters and their resilience. Several post-disaster studies have found that there was notable prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression in the Haitian population. They have faced many political, economic, and environmental storms to include natural disasters (Nicolas et al, 2014, p. 93). Nicolas (2014) argues that the sociocultural traditions and customs of the Haitian people, family, religion, and community, are the reason for their resilience in the face of disaster.

Some refer to the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath as a “collective trauma,” defined as the “psychological response of an entire group to a traumatic event, such as the Holocaust” (Kaubisch et al, 2022, p. 28). From a psychological point of view, the threat of serious illness or death, the loss of jobs, the increased stress, the disruption in daily lives, the growing uncertainty, and the disconnect and isolation generated by the pandemic led to the consideration of COVID-19 as a traumatic event. Research suggests that one in five people could experience psychological distress post-COVID-19, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Kaubisch et al, 2022, p. 27).

Prior to COVID-19, Haiti had just lifted restrictions from a political lockdown that had lasted almost a year and the country was also experiencing violent civil unrest triggered by an abrupt increase in fuel prices, a movement that became known as Peyi Lòk (Blanc et al, 2020). “When the first case of COVID-19 arrived in March 2020, the country was just beginning to regain a certain sense of normalcy despite the socio-economical and psychological ramifications of being on lockdown” (Blanc et al, 2020). Majority of the Haitian population continued to live their daily lives, as they were desensitized to the effects of disruption and forced isolation and distancing. Within three months, COVID-19 in Haiti had reached its peak and there was a decrease in the number of detected cases, predicting that the damage of the pandemic would not be too devastating to the country (Blanc et al, 2020).

It is argued that other countries, such as the United States, could learn from the Haitian experience of coping with traumatic events. Resilience is possible after exposure to trauma. Factors that promote posttraumatic growth are “positive social support, gratitude, strong family ties, attachment, and meaning making, or the way in which a person interprets or makes sense of life events” (Rousseau, 2023). The country of Haiti was created after the only successful slave insurrections in history and the resilience of that revolution threads through its history of tremendous struggles.

References:

Blanc, J., Louis, E.F., Joseph, J., Castor, C., & Jean-Louis, G. (2020). What the world could learn from the Haitian resilience while managing COVID-19. Psychological Trauma, 12(6), 569–571.

Kaubisch, L.T., Reck, C., von Tettenborn, A., & Woll, C.F. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic as a traumatic event and the associated psychological impact on families – A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 319, 27–39.

Nicolas, G., Schwartz, B., & Pierre, E. (2014). WEATHERING THE STORMS LIKE BAMBOO: The Strengths of Haitians in Coping with Natural Disasters.

Rousseau, D. (2023). Module 1: Introduction to Trauma. Blackboard.

Self-Care for Trauma Victims

People across the globe face traumas on a daily basis that leave long-lasting impacts. Some individuals rise above the occasion and overcome the travesties they’ve endured; however, some people are left not knowing how to properly cope. Trauma forever changes our brains. We face a devastating event, and our brains go into fight, flight, or freeze mode and some never leave those stages. This is where trauma and its negative consequences create problems in one’s day to day life. So, how do we move forward and past our traumas? How do we return to a state of homeostasis and mental stability to live a fulfilling life? Well, self-care is one of the most important practices one can utilize to help overcome their traumas.

Self-care is all about establishing practices to ensure one’s overall well-being, something trauma victims have difficulty achieving. There are many ways to accomplish this and there isn’t a “one size fits all” form of this. Many self-care practices are available as some work better than others depending on the person. Some common self-care methods are reading, taking a bath, watching your favorite TV show, spending time with friends and family, all things that would make you feel good (Hood, 2018). While important to remember to do things that make you happy, it is also important to remember to allow oneself to feel all emotions as they come (e.g., rage, sadness, defeat, grief).

One method of self-care found to be beneficial is journaling. Journaling allows oneself to express themselves and their emotions in a non-biased environment (van der Kolk, 2014). It creates a space for us to process our traumas and our feelings around it and further work through it. In fact, journaling has been shown to reduce rumination, the unhealthy practice of replaying painful events over and over again in your mind (LivingUpp, 2023). Using the pages of a journal give you a dumping ground for negative emotional energy creating some relief in the end. Journal also helps identify patterns; when you journal frequently about the same person, situation or worry, it clues us in to what need some further investigation (LivingUpp, 2023). This would further help us work through that specific problem area and move on with our healing.

Another helpful form of self-care is meditation. This is something we often see used in yoga, too. Meditation has been shown to not only calm someone, but also helps with anxiety and depression, cancer, chronic pain, asthma, heart disease and high blood pressure (Mental Health America, 2023). This self-care practice presents a state of peaceful mindfulness, allowing us to channel our energy into healthy lifestyle practices. This, again, is another tool that effectively allows trauma victims to work through their traumas and go on to live a happy and healthy life (van der Kolk, 2014). Meditation gives us the space to begin healing again.

Overall, there are several forms of self-care practices in which are effective and beneficial to those utilizing them. Those mentioned above just barely touch the surface. However, simple practices as those are a great way to begin the journey to healing. Trauma is a forever life-changing thing, and it takes a lot of work and time to heal from it. Starting the process with something as simple as reading your favorite book or treating yourself in another way, is just the beginning of the good to come when one practices self-care.

References

Hood, J. (2018, December 20). The importance of self-care after trauma. Highland Springs Clinic. https://highlandspringsclinic.org/the-importance-of-self-care-after-trauma/#:~:text=You%20can%20do%20this%20by,during%20the%20trauma%20healing%20process.

LivingUpp. (2023, December 10). Journaling as self-care. https://www.livingupp.com/blog/how-to-journal-for-self-care/#:~:text=Health%20Benefits%20of%20Journaling,-Journaling%20has%20many&text=Expressing%20your%20thoughts%2C%20fears%2C%20and,over%20again%20in%20your%20mind.

Mental Health America. (2023). Taking good care of yourself. https://mhanational.org/taking-good-care-yourself

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Overcoming Barriers to Trauma: Rural Women Facing Domestic Violence

Riley A. Thomas

Considerations surrounding rural and sparsely populated America and its criminogenic nature are overlooked. Therefore, much needed attention on rural centric crime considers factors not applicable to the urban. This fact may be related to issues that make society as a whole precieve rural criminology less important than metropolitan areas (Ceccato, 2018), where a majority of the American population lives. Therefore, a much greater emphasis and attention is needed for victims of traumatic crimes in rural areas due to the spatial differences than percieved mainstream criminology.

Aspects such as limited access to services, isolation, poverty, and rural cultural values make rural women more vulnerable to domestic violence than women living in urban areas (Ceccato, 2015). This post will mainly focus on rural women who suffer from intimate partner violence (IPV), and the geographic challenges of recieving treatment or support outside of the immediate area.

Examining intimate partner violence in this case is significant because it can be evaluated as one of the most underreported figures of crime. For example, Ceccato (2018) identifies that physical isolation may also lead to a disproportionately high declared fear of crime

because of individuals’ relative vulnerability. For a variety of reasons, women and victims of IPV may fall silent due to public perceptions, shame, guilt, or embarassment to name a few (van der Kolk, 2014). Reagrding trauma related to IPV, rates for violence against women vary geographically, making it difficult to untangle underreported cases between rural and areas (Ceccato, 2015). Additionally, the cohesive nature of rural areas adds another dimension of trauma support avoidance.

This consideration of a cohesive system stems from smaller communities being well versed with eachother, and the events that take place within the community. In other words, everyone knows everyone, and collective efficacy is rarely thrown off balance. Knowing this, woman may avoid support for their trauma with the fear of being ostracized by speaking out on violence, which may have the unintended effect of enabling domestic violence, and the inability to seek help for IPV trauma (Ceccato, 2015).

Knowing this the geographical difficulties of seeking help in rural IPV and trauma cases still remain prevalent. For example, rural communities and towns are in far geographical areas from metropolitan areas with greater support systems. In other words, long distances create isolation to a greater degree than urban areas (Ceccato, 2015). With these outlets out of reach, rural communities may lack the resources and support systems and highly populated areas have. This can lead to victims of trauma and IPV staying silent, since breaking the efficacy and cohesion of their community can have drastic effects on the abuser and the victim. The lack of support systems for women in rural areas can contribute for women to stay in their traumatic situations. Victims of traumatic domestic violence often cover up their abusers (van der Kolk, 2014) for a variety of reasons. Here, I can assume because of the limited access to getting treatment, and the unwillingness to face public embarrasmenterassment. Since the cohesive nature of small communities may put these victims of trauma in the shadows.

This post considers the challenges rural women may face when dealing with IPV and seeking treatment for their trauma. Knowing the spatial differences between the rural and the urban seek out potential barriers for women to attain the help that they need, due to factors such as isolation and reliance on their domestic partner. An attention on rural centric crime considers factors not applicable to the urban, and must be researched further to understand the hidden figures and perception of rural life.

Ceccato, V. (2015b). Rural crime and community safety. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203725689

M.D., B.V.D. K. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin US. https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9781101608302

Approaches to Childhood Trauma

I have always found the psychology of children a fascinating topic because much of our habits, actions, and language developments occur during our childhood years. So, I was excited to learn more about childhood trauma; more specifically, how children are impacted by trauma. Unlike adults, children experience, express, and cope with trauma differently compared to adults. Because of this, psychologists and psychiatrists have had a hard time recognizing and managing children who experience trauma. Although there are many tests to help guide these professional workers in diagnosing these children. In the documentary “PTSD In Children: Move in the Rhythm of the Child” directed and produced by Joyce Boaz, she highlighted the idea that there are children who are experiencing trauma who seek interventions, but there are children do not seek interventions. Children are vulnerable to their surroundings and their environment due to their sensitive nature. Trauma does not only change their perceptions of the world but also changes their neurobiological development (Rousseau, 2023).

A biology approach to childhood trauma:

Kolk’s chapter on “Developmental Trauma: The Hidden Epidemic” discusses the idea that trauma and stress may be involved in a more-than-just environmental impact, but rather could be a transfer of genetic makeup to progeny generations (Volk, 170). This idea is not a new idea, with understanding if our genes give rise to certain behaviors and traits. However, strong research has also found the importance of epigenetics which can certainly change behaviors (Kolk 2015).

Currently, I am taking a course in Animal Behavior, and one of the case studies we looked at is the idea that genetics influences an individual's primary response, however, epigenetics (aka the impact of the environment on our DNA) can change this primary response. Similar to Szyf’s words, “major changes to our bodies can be made not just by chemicals and toxins, but also in the way the social world talks to the hard-wired world.” (Kolk, 2015)

A social approach to childhood trauma:

Now that we discovered the idea that trauma may impact a child differently depending on their innate genetic information, different children will respond and react to trauma differently. The “hard” part of this is how researchers can determine this. In Boaz’s documentary, she introduced us to multiple psychiatrists who specialize in treating children who have experienced trauma, and a consensus that all the psychiatrists agreed on is that children are hard to read. Sometimes they are unable to identify and express their feelings, and for this, therapeutic tools as well as diagnostic tools have been implemented to assist psychologists and psychiatrists to help with diagnosis and treatments. In our course, we looked at multiple different therapeutic tools including the art of yoga project, Sand Tray Therapy, and Trauma-Informed Behavioral Therapy (Rousseau, 2023).

These tools and approaches are important for early interventions of children who experienced trauma, but I do want to recognize children who are unable to find interventions. The ACE study (Adverse childhood experiences) found with a sample size of 50,000 patients that:

* One out of ten adults responded that he/she was a victim of some form of emotional abuse.

* More than one-quarter of respondents were victims of some form of physical abuse.

* Twenty-eight percent of the adult women and sixteen percent of the adult men responded that they were victims of some form of sexual abuse.

* One in eight of the adults responded that he/she witnessed his/her mother being a victim of abuse.

(Taken from Rousseau 2023)

In simple terms, trauma impacts a lot of children, and it continues to impact millions of children through different routes such as domestic abuse or school bullying. From 2021-2022, a total of 327 documented school shootings have occurred in US elementary to high school (National Center for educational statistics, 2023). This speaks words to not only the individuals who are causing the school violence but also individuals who experience the school violence. Domestic abuse has also been coined as a public health issue. Intervention is only provided when an individual seeks it, so I find it extremely disheartening for those who cannot seek it or don’t know how to seek it. Although there are many techniques and therapies involved, at the end of the day, only certain types of individuals can receive it.

References:

National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Violent Deaths at School and Away From School, School Shootings, and Active Shooter Inceidents. Retrieved December 9, 2023, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a01/violent-deaths-and-shootings

Boaz, J. (Director + Producer). (1995). PTSD In Children: Move in the Rhythm of the Child.

[Video/DVD] Gift from Within. https://video-alexanderstreet-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/watch/ptsd-in- children-move-in-the-rhythm-of-the-child/details?context=channel:counseling-therapy

Rousseau, D. (2023). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 1. Retrieved November 20, 2023,

from Blackboard.

Van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, And Body in the Healing of

Trauma. Penguin Books.

childhood trauma

Childhood trauma, which includes experiences such as abuse and neglect, casts a long shadow on one's life, leaving indelible marks on one's mental health and relationships. Based on my personal experiences with difficulties, I've realized the profound impact it has on emotional well-being. Addressing childhood trauma is critical for healing, requiring compassion for oneself and a commitment to breaking the cycle of pain.

Childhood trauma is frequently manifested in mental health issues ranging from anxiety to depression. My journey has taught me the value of acknowledging the impact, encouraging open dialogue, and breaking the silence surrounding these experiences. By sharing our stories, we not only de-stigmatize the conversation about trauma, but also create a safe space for healing and resilience. Seeking professional help, participating in therapies, and developing a trusting network are all important steps in the ongoing journey toward recovery and self-discovery.

TRAUMA AND DISSOCIATION IN CHILDREN

Dissociation is a survival mechanism and one that is often ignored in traumatized children. All humans have a natural ability to mentally ‘leave the room’ when their trauma is utterly unbearable. Dissociation is vital for infants and children who are suffering frightening things, it enables them to keep going in the face of overwhelming fear.

A child often continues to dissociate even when they are no longer in danger. Their brain cannot turn the coping strategy off. The more frightening a child’s traumas are, the more likely they are to dissociate; and children in ongoing danger will develop more and more sophisticated ways to dissociate. Child trauma is much more common than we perceive (Rousseau, 2023). As a result of the trauma, children can dissociate themselves. Dissociation is the essence of trauma, and a person disconnects from their thoughts, feelings, memories, or sense of identity (Van der Kolk,2014). According to Van der Kolk, child abuse and neglect is the largest public health issue facing our nation, and it is the most expensive and devastating thing that can happen (Trauma and Dissociation, 2007). Childhood trauma is the largest public health problem (Rousseau, 2023).

According to Danielle Rousseau, factors that hinder child development where a child suffers

traumatically can be due to physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, neglect, separation from

parents, or rejection from parents (Rousseau, 2023). Dissociation manifests in feeling lost,

overwhelmed, abandoned, disconnected from the world, and in seeing oneself as empty,

helpless, trapped, and weighed down (Van der Kolk, 2014). Dissociation is an intriguing

technique of survival, but the most devastating long-term effect of this shutdown is not feeling

real inside, where the trauma is kept alive.

Dissociation is learned early. Infants who live in secure relationships learn to communicate not

only their frustrations and distress. Caregivers ignore your needs or resent your existence

you learn to withdraw (Van der Kolk, 2014). A child is still developing and are dependent on

their caregivers, they are unable to resolve their trauma as it is a complex and complicated task.

Dissociation, then, becomes a common defense mechanism that a child develops to create a less

painful and terrifying world in their mind.

Children with trauma are more likely to experience dissociation. While some level of dissociation is normal; we all do it. Dissociation allows a person to function in daily life by continuing to avoid being overwhelmed by extremely stressful experiences, both in the past and present. Even if the threat has passed, your brain still says “danger.” However, if it continues into

adulthood it becomes an automatic response, not a choice. As children with trauma get older, they may use self-harm, food, drugs, alcohol, or any other coping mechanism to maintain the disconnection from unhealed trauma.

Art and play therapy are common because they help the patient express the trauma when it is too difficult to express it verbally.

References

(2007). Trauma & Dissociation in Children I: Behavioral Impacts [Video file]. Cavalcade Productions. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from Kanopy.

Rousseau, D. (2023). Trauma and Crisis Intervention. Module 2. Childhood Trauma. MET CJ720. Boston University.

Van der Kolk, B.A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking Penguin.