Can Playing Dungeons & Dragons Be a Trauma Treatment Tool That Bridges the Victim-Offender Overlap?

It’s close to midnight when your party enters the roadside inn half a mile outside of the town of Waterdeep. You’re a rogue and thief wanted for murder, so you conceal your face. While your friends make their way over to the bar, you slink into a booth in the darkest corner of the dining room. As you note all the possible exits in the building, a waitress meets your gaze and begins to make her way over to where you are sitting. Before she can get close, two strangers block her path and start speaking to her in hushed but insistent tones. You succeed in rolling a perception check. The waitress seems extremely distressed, and you hear her say, “I said ‘no,’ now leave me alone.”

You’re a rogue and a thief. It would be best if you didn’t make a scene, but your character sheet also says that part of your background is that your family abused you, and you vowed never to let an innocent person be hurt by someone else. Your friends are distracted at the bar and don’t see the woman who needs help. It’s up to you. You roll a successful intimidation check and put a hand on the shoulder of one of the aggressors. “She asked you to leave,” you say. Thankfully, the strangers leave the inn, only looking a little annoyed. “Thank you,” the waitress says, stopping short when she sees you more clearly. Recognition flashes across her face. “It’s you!” Well, here it comes, you think. Off to jail, again. “Everyone, everyone!” she says, “It’s The Savior of Baldur’s Gate! Get this hero a drink!!” Oh yeah, you remember, I guess we did save that city a few sessions ago. Word travels fast.

~

In the first discussion post for this course, I was instantly drawn to van der Kolk’s (2015, p. 17) observation about imagination: “Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives [and] it is the essential launchpad for making our hopes come true.” From victims of child abuse using sand to play and act out narratives that they may not remember the words for (Rousseau, 2023b, p. 16) to veterans of war struggling to see peaceful images in inkblots (van der Kolk, 2015, p.16) to offenders of horrific crimes having to live with the trauma of institutionalization on top of learning to live a crime-free life (Rousseau, 2023c, p. 15), imagination is the most essential tool to build resilience in environments where inspiration is in short supply.

While the story I wrote above might seem goofy to you as the reader, I believe that as the player, and as your own main character, the choices you make and the actions you take can be exhilarating, and important at the very least. This is why I think we love knowing a little bit about our star sign, and why we take all those surveys that tell us which character of whatever TV show we would be. This can be a fun reverie for anyone, if, of course, your horoscope says you’re going to win the lottery and you’re most like the protagonist, hot girl, cool guy, etc. For people who may avoid their past or find that they are unable to leave their past behind them, I believe games, like trauma-informed Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), can be used to practice imagination, act as a complex form of talk, group, and exposure therapy, and instill a long-lasting resilience in people who have experienced many different forms of trauma and chronic stress.

If you’re unfamiliar with D&D, this is a great synopsis of the game, written by Blakinger (2023), who interviewed inmates on death row who used the game to cope with their death sentences: “[D&D is a] tabletop role-playing game known for its miniature figurines and 20-sided dice. It combines a choose-your-own-adventure structure with group performance[.] Participants create their own characters — often magical creatures like elves and wizards — to go on quests in fantasy worlds. A narrator and referee, known as the Dungeon Master, guides players through each twist and turn of the plot [with] an element of chance.”

Before you discount me completely, remember that playing games that improve our “physical, mental, emotional, and social resilience” can add years to our lives (McGonigal, 2012; Rousseau, 2023a, p. 8) and individuals who have experienced trauma and chronic stress may already have had the physical effects of stress take years off their life (Rousseau, 2023a, p. 4). Rousseau (2023a, p. 4) lists “uncertainty, loss of control, and a lack of information” as factors that trigger stress. It is unrealistic to imagine a future in which none of these factors occur, but the human body’s response to stress (van der Kolk, 2015) calls for treatment in safe spaces where we can learn how to deal with this natural response to past trauma. With every roll of the dice, the success of your decisions in this game is left completely to chance, but the player is always in control of what they decide to do and how they respond to successes and failures. While there is a lack of information, the Dungeon Master knows everything about this fantasy world. There are boundless opportunities to learn, explore, and discover the unknown.

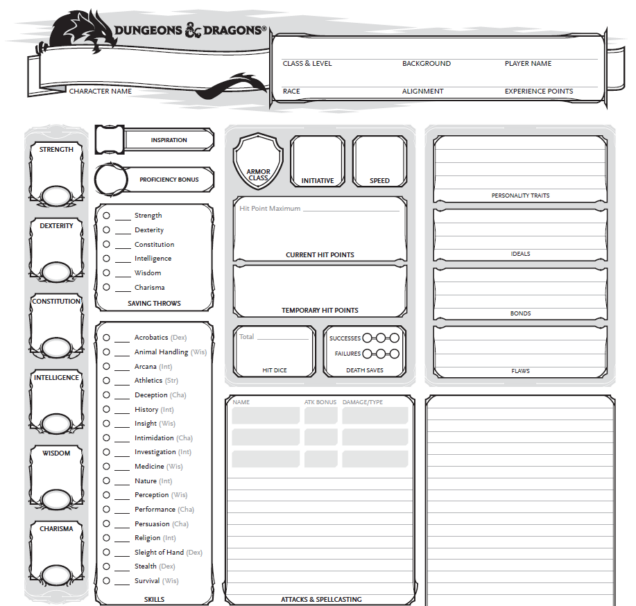

In addition to the safe space that this game creates as a practice zone to cope with stress and possibly even face one’s fears, I believe that D&D can also be used as a tool for reclaiming positive narratives and labels, particularly for offenders. Labeling theory states that “people become stabilized in criminal roles when they are labeled as criminals” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 7). A tool known as “redemption scripts” (Cullen et al., 2022, p. 248-250) has been used in efforts for people to discover their “true selves” or the best parts of them that could be the foundation for a crime-free life. I believe with guidance from a therapist or other trained mental health professional, the character creation portion of this game, which often takes place one-on-one and before the roleplaying part of the game, could be beneficial to offenders seeking a personal label change.

While this is just a brief exploration of this idea, it would be very interesting to see how resilient trauma-impacted individuals both inside and outside of prisons were after just a few sessions of playing D&D, and if they thought about their fantasy adventures outside of the sessions at all, and in what way. If you’ve never played D&D, I understand it might be confusing to think about how powerful this game can be. But, before you go, please look at the picture below. This is a D&D character sheet. It’s what you fill out for the character you play during the game. This is where you list your character’s strengths, weaknesses, background, personality, and if you’re inherently good, bad, or just straight chaotic. If you have a moment, read the categories on the sheet, and think about two things: 1. What would this sheet look like if I were the character in the story? Particularly, what would the four categories on the righthand column say? And 2. If I could be anyone, my true self, what would it say then?

Thank you very much for keeping an open mind, maybe learning more about something new, and considering my perspective!

(D&D Blank Character Sheet, 2023).

References

Blakinger, K. (2023, August 31). When Wizards and Orcs Came to Death Row. The Marshall Project. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/08/31/dungeons-and-dragons-texas-death-row-tdcj

Cullen, F. T., Agnew, R., & Wilcox, P. (2022). Criminological theory: Past to present (7th ed.). Oxford University Press.

D&D Blank Character Sheet [PDF]. (2023). Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://dnd.wizards.com/resources/character-sheets

McGonigal, J. (2012, June). The game that can give you 10 extra years of life. TEDGlobal 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_the_game_that_can_give_you_10_extra_years_of_life

Rousseau, D. (2023a). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 1. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023b). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 2. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

Rousseau, D. (2023c). Trauma and Crisis Intervention Module 6. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from Blackboard [url].

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, And Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.