The Break Out: Waiting on change for years, the Chargers are still the Chargers

(Photo courtesy of NFL.com)

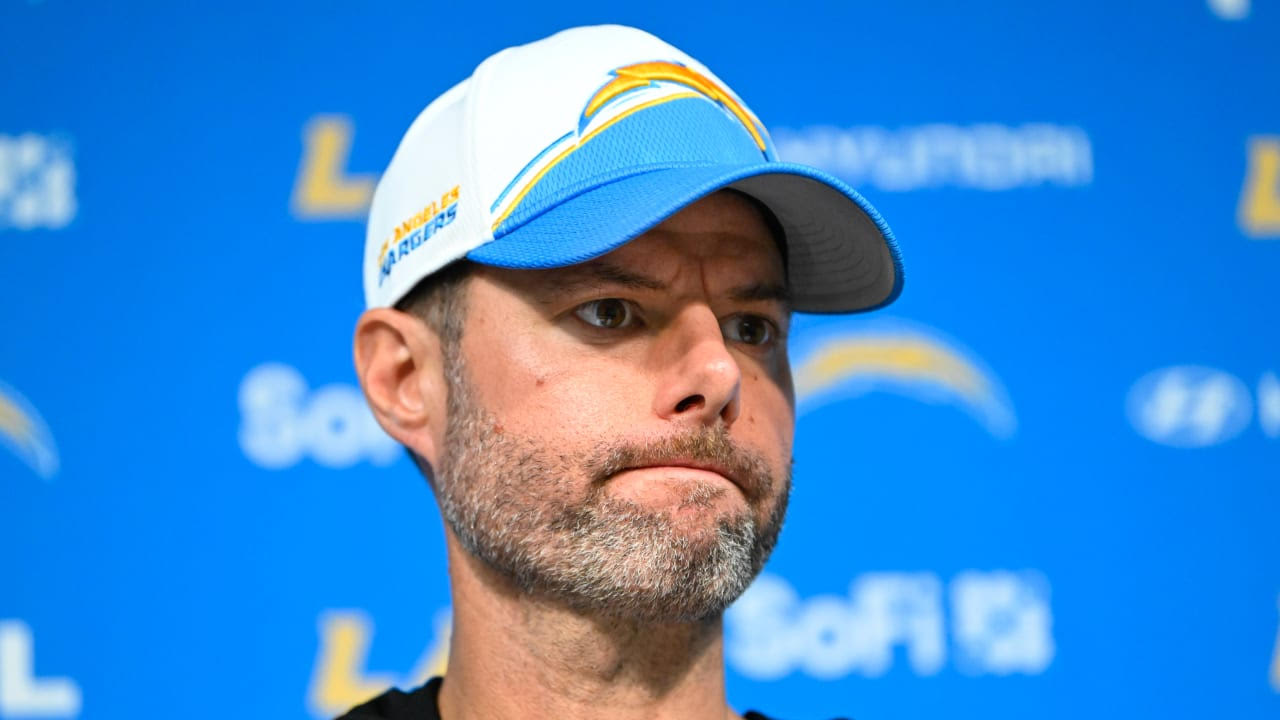

The Chargers hired Brandon Staley because he was a modern thinker who pushed the envelope. 37 games later, the same problems are handcuffing an uber-talented roster

By Sam Robb O’Hagan

Presumably, Brandon Staley is tired of answering questions about The Jacksonville Loss. See for yourself.

Staley’s Chargers are 0-2 since, after a calamitous, infuriating, and entirely preventable 27-24 overtime defeat to the Titans. Those have become familiar adjectives.

The Jacksonville Loss — the third-largest meltdown in NFL postseason history — may or may not loom within the walls of the Chargers’ locker room. Staley, transparent in his hostility, insists it doesn’t.

But, and this is about the best articulation of just how dire things are becoming in Los Angeles, there are tougher questions for Staley to answer.

Particularly — 37 games into Staley’s tenure, why does such a talented roster have just one playoff loss to show for it? And why, in what was supposed to be the year the Chargers finally took the next step, is Staley storming out of press conferences after only two weeks?

The answer doesn’t lie on offense. Most frustrating, perhaps, is that offensively, the Chargers are actually good. Again.

Justin Herbert shines, and he shined bright again on Sunday. Keenan Allen and Mike Williams are a top receiver duo. Through two weeks, the Chargers offense is fifth in Expected Points Added per play and third in success rate (the percentage of plays that generate positive Expected Points), per rbsdm.com. Led by new offensive coordinator Kellen Moore, LA’s offense is humming.

The offense has continued to churn. The team has continued to lose.

Because on Sunday, Los Angeles was poorly coached. Their defense couldn’t get off the field when they needed to. And, once again, their handling of their affairs was actively counter-productive.

All four of Los Angeles’ penalties were on third down. On 3rd and 13, facing a slant route five yards short of the sticks and smothered by two extra defenders, veteran safety Derwin James went for the head and laid out the Titans’ receiver. Automatic first down. Three plays later, on 3rd and 12, a roughing the passer penalty on veteran pass rusher Sebastian Joseph-Day. Automatic first down. One play later, touchdown.

Later, on 3rd and 4, with four minutes left and defending a four-point lead, another roughing the passer penalty, this time on Kenneth Murray, a first-round pick. A minute later, touchdown. 24-21, Tennessee.

That’s 29 yards worth of third down ground faced by the Titans’ offense, and 45 yards gifted by the Chargers’ defense.

So, the penalties are one thing. But entirely another are the yards surrendered in exactly the manner this defense was assembled to prevent. Staley has preached preventing explosive plays since the moment he burst onto the scene as a defensive assistant and, if not to solve the Chargers’ chronic shooting-themselves-in-the-foot problem, at the very least, Staley was brought in to prevent big plays.

On the Titans’ first touchdown drive Sunday — a 70-yard completion to Treylon Burks that put the ball inside the five. On their last, deep in their own territory trailing by three with six minutes left — a 49-yarder to Chris Moore to advance the ball across midfield.

Staley’s defense leads the league in yards allowed per pass attempt by half a yard. They’ve given up 12 explosive plays (defined as a gain of 20 yards or more) in two games.

The Chargers sent a second-round pick to the Bears for pass-rusher Khalil Mack — who is worth $16 million against the cap this year — and he’s recorded eight sacks in 19 games. They gave cornerback J.C. Jackson a contract worth $17 million against the cap, the highest number on the team, and he played only 41 of the 65 defensive snaps on Sunday.

Staley’s defensive scheme isn’t performing, and the players he brought in to enforce it aren’t performing either.

Then, of course, there’s the shooting-themselves-in-the-foot problem. It’s worth remembering, and it’s certainly become easy to forget in Los Angeles, that all of this is supposed to be easy. This is the stuff you don’t even have to do, but the stuff you simply have to avoid doing.

And yet:

Overtime. 3rd and 1 for the Titans on the Chargers’ 39-yard line — an obvious rushing down for the most rush-heavy team with the league’s most dominant short-yardage rusher. By some stroke of luck — yes, luck for the Chargers — Derrick Henry isn’t on the field.

Timeout, Chargers. Henry retakes the field and proceeds to bowl his 6-foot-3, 245 pound frame into a pile of bodies and will his way to a first down, the type of play that Tyjae Spears wouldn’t even attempt, the 5-foot-10, 200 pound running back on the field before Staley called timeout.

Game over.

Not the stuff Staley had to do, the stuff he simply had to make sure he didn’t. Not the target Staley had to point the gun, but the target, the only target, the Chargers desperately needed him not to — his own foot.

“The mistakes we made out there, we can correct all of them,” Staley said after the game.

He’s right. The Chargers know that all too well.

This is about far, far more than The Jacksonville Loss. It’s about The Denver Loss the week before, when Staley played his starters in a meaningless game and watched one of his best offensive players fall to injury. It’s about The Las Vegas Loss the year before that, when Justin Herbert did everything he could and more, like he so often does, and Staley’s defense couldn’t get a stop. It’s about all of The Kansas City Losses in between, all of them within one possession, a lot of them in overtime.

And it’s also about The Buffalo Loss, 1,023 days ago now, when Anthony Lynn took needless timeouts, wasted valuable clock, and managed the game so poorly that he left Los Angeles almost no choice but to force him out of the seat Staley would eventually assume.

And, of course, it’s now about The Tennessee Loss, yet another notorious Chargers’ loss, which reeked of each of the stinks that caused the others.

It would be worth it for the Chargers to ask Staley questions about Those Losses, too, because it’s becoming unmistakably clear that he doesn’t have the answers.