Evernote changes privacy policy: ‘We might look at your notes’

The intertubes are lit up today with righteous indignation after popular note-saving app Evernote announced a change in its privacy policy that basically says, "One of our employees might take a look through the notes you trusted us with." Here's the official statement.

I have several thoughts on this, especially since I've been using the service for many years.

First. It might be that Evernote has received one or more National Security Letters or warrants from the secret US FISA court and this is their way of putting their users on notice that they are obligated to turn over user data. We've seen several high-profile companies (including Apple) kill off their warrant canaries in the past few years, but I think that at this point we can pretty much assume that these warrants and letters are being served across the board. There are simpler ways of telegraphing an NSL than changing a subscriber privacy policy. NSL's come with a gag order preventing the recipient from disclosing them, so it wouldn't make sense to change a policy in response to this kind of order.

Second. Evernote provides a free tier that, while not as generous in terms of storage as others, is adequate for the casual user. There is no such thing as 'free' on the internet; if you aren't paying for a service, your data is being mined out the wazoo. It is scanned, analyzed, stored, sold, and otherwise wrung out for every dime that the provider can make off of you. I would guess that even Evernote's paid tiers are subject to some kind of meta-data analysis. As in the first case, this is assumed and wouldn't require a policy change.

Third. One of Evernote's marketing points is that it a seamless way to store and reference your day-to-day information. They're doing some heavy lifting on the back end in terms of indexing, predicting, and optimizing the way that they present information to their users. The communication from Evernote around their policy change hints at this being the reason to allow their employees to see stored notes, that they want to optimize their processes with human intuition, and to be honest it's the most likely reason that I can think of.

I'm giving Evernote the benefit of the doubt. I think that they are being as upfront as they can about this policy shift, with the understanding that there will be a period of indignation, and that they will lose a small number of customers. When I read the news, the first thing that I did was to spend half an hour looking for alternatives to Evernote. My conclusion is that Evernote is unique in its feature set and that there just isn't any service or software that is as convenient or comprehensive as Evernote.

There's a however, however.

Any file that you store in the cloud is no longer under your control.

You absolutely have to keep this in mind every time you sign up for a service like Evernote, or Google Docs, or OneDrive, or Snapfish, or any of the other thousands of sites that want to feast on your data. If you aren't paying for it (and sometimes even if you are), YOU are the product. Your information is being sold to third parties for a profit.

The bottom line is this: Do not use any cloud service to store private information.

Even services that allow you to 'password protect' information (Evernote, OneNote, etc.) should not be trusted. If the file is on someone else's server, you must assume that it has been compromised. There just isn't any way to prove that it hasn't been. If you don't want anyone else to see your data, it should be stored on your personal computer and encrypted.

So, will I continue to use Evernote after this shift in their policy privacy? I will. I didn't trust them with sensitive information before, and I don't now. But I don't think that the collection of risotto recipes that I've built up over the years is going to land me in jail. I maintain a very clear line between data that I know will be scanned and divulged and data that is private; the latter is never stored on a server or computer that I don't control.

What I’m Using for Privacy

In the past weeks I've been thinking a lot about online privacy. I've been setting up a new Mac (a Hackintosh, to be precise) which means that I've been installing my day-to-day software. Many of these programs are ones that I've chosen over the years specifically to enhance my online privacy and aren't 'stock' applications.

Over the next few posts I'll go over each piece of my privacy puzzle and explain why I chose it over the standard applications. As a collection I think that they represent a pretty good start at locking down my online presence, and you might find my thought process useful. I'm also open to constructive criticism...if you think I've missed something, let me know.

I'll list what I'm using in the following table and and provide links to the individual articles explaining my choices as they are written.

| Category | What I use | Instead of |

| Thunderbird | Apple Mail, GMail etc | |

| IM | Signal | Anything |

| Cloud | SeaFile | Any commercial service |

| Cell / voice calls | Facetime | Just dialing a number |

| Encryption | PGP | Not encrypting |

| Web search | DuckDuckGo | |

| Browser | Tor Bundle | Safari |

| Operating system | MacOS | Windows |

It’s time to get serious about personal privacy

Today as I was driving my dog, Maggie, to the park for her afternoon walk, a pickup truck pulled up behind me at a stop light. I wouldn't normally think twice about the car behind me, but this one had a very obvious Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) mounted on the dash, and I could see the driver behind me fiddling with it. My assumption was that he was either enabling it or saving a capture of my plate.

If you don't know what an ALPR looks like, the next time you see a BU Parking Services truck go by, look for two rectangular devices mounted to the roof, one on each side. At BU they are used to ferret out cars that are parked in lots where they shouldn't be...the truck drives up and down the rows, scanning plates, comparing them to the Parking Services database of pass holders.

I've lived in my town for going on a decade now, and I'm familiar with the law enforcement vehicles in use here. This wasn't one of them, and there were no markings to indicate that it might be from another town or perhaps a state vehicle. My take was that it was a private vehicle.

Why was this person reading my plate?

I have a Johnson/Weld sticker on the back of my car. My very first thought was that someone wanted to know who I am, maybe because of my political affiliation.

I understand that this sounds like a paranoid conclusion. However, consider two points:

- Under the Obama administration, the power wielded by the NSA, FBI, and CIA have grown to unprecedented levels. Ed Snowden revealed a small part of the domestic surveillance being undertaken by these agencies, and they made headlines for about one week. Afterward the country moved on to who was winning Dancing With the Stars. Our government is intercepting every email, text message, and phone call made in this country. Eavesdropping warrants and gross violations of our privacy are approved by a secret court. We are murdering innocent people by silent drone attack in sovereign nations on a regular basis. As a country we just don't seem to care.

- The incoming Trump administration does not appear to be pro-privacy. In fact, they seem quite the opposite. Donald Trump is being handed a domestic surveillance capability unsurpassed by any government and I believe that he will use it to its fullest extent. Worse, a naive, unskilled Trump administration combined with our current public apathy is the perfect environment for our intelligence agencies to aggressively attempt to expand their reach.

In this environment, an active ALPR mounted in an unmarked vehicle recording my plate is a threat.

The question is, then, what to do? To this point privacy advocates have encouraged us to secure our email, and chat, and voice messages, but with the caveat that yes, it's not always easy, and yes, this is how you should do it but we understand that you probably can't because it's too hard.

It's different now.

I've always assumed that my emails, my phone calls, and the web sites I visit are recorded. Not because I'm someone that needs to be watched ... it's just that I understand, based on the evidence I've seen, that everyone's information is being recorded. I've advocated for privacy while personally falling short -- I've fallen victim to the 'too hard' argument, and to the idea that my small voice will be lost in the cacophony of an entire country's worth of data.

It's different now.

I can only be responsible for myself. Encryption is now my default. I've encrypted the disks on my computers, and all of the backups. I'm actively encouraging everyone that I regularly message with to switch to Signal, which encrypts text messaging end-to-end. I've migrated from Apple Mail to Thunderbird because the latter better incorporates email encryption. I've switched my default search service from Google to DuckDuckGo because the latter promises to not store my online search history and is secured with HTTPS. My voice calls are made using Facetime rather than the standard cell phone connection because Facetime is encrypted end-to-end. I find myself using Tor more and more often (even as I acknowledge its shortcomings).

Even though I have nothing to hide, I am hiding everything.

It's different now.

If you need help securing your personal communications, I am happy to help. You can reach me at perryd@bu.edu; if you are able, please encrypt your email. If you aren't able, I can help with that, too.

Which VPN Should I use?

Recently one of my students asked for a recommendation on a VPN app for his Macbook. I thought my rather long-winded reply might be useful to others wondering the same thing, and it's appended below.

There are two primary use cases for a VPN:

- You are away from your home network, possibly on an unsecured network such as in a café or an airport, and want to encrypt all of the network traffic coming to and from your computer (even traffic that isn't normally encrypted)

- You want to appear to be somewhere else in the world. I ran into this when I wanted to watch World Cup soccer matches not shown in the US but available in the UK; I set up a VPN connection to a server in London so that it appeared I was in that city, and then watched the games on the BBC.

Here's my reply to my student's question:

The short answer is that I don’t trust the apps on the App Store for VPNs. The longer reason…all of them provide their own server to connect to, which means that my VPN internet traffic is going through an endpoint that I don’t control. The only assurance I have that my traffic isn’t being decrypted, stored, or otherwise manipulated is that the app seller tells me that they don’t. Also, the programs are not open source, so I can’t look through the code to assure myself that there is no back door or other security risk.

For that reason, I use Tunnelblick on the Mac (https://tunnelblick.net), which is an open-source VPN program. I have very high confidence that it hasn’t been compromised. I run my own VPN server (which I personally built and maintain) to connect Tunnelblick to when I’m away from the home network, so the encrypted tunnel goes from my Macbook, through the Tunnelblick VPN, into my own server, and from there out onto the internet. The use case is typically that I’m away from home, on an insecure network, and want to lock down / encrypt everything going over that network.

That being said, if my purpose is to connect to a VPN so that it appears I am somewhere else, such as if I want my internet address to be in the UK to watch soccer, I’m forced to use one of the commercial VPN providers, and for that I use Tunnelbear, https://www.tunnelbear.com. Note that this is not open-source, and so your confidence in it in terms of privacy should be very low. They do get good reviews, and I’ve had a $5/month subscription with them for about three years now. I generally use Tunnelbear for very specific purposes (such as location shifting) and take steps to make sure that no other traffic is going through their VPN endpoint (I use Little Snitch firewall rules to accomplish this).

On the iPhone/iPad side I use OpenVPN (https://openvpn.net), but again I’m connecting back to my on VPN server with it. It’s an open-source project that I have high confidence in.

OpenVPN offers PrivateTunnel, with a pay-as-you-go connection plan that is fairly inexpensive. It’s the same team that produces OpenVPN, so I would trust them a little more. The ‘tunnel’ is a VPN connection back to one of their servers, and so you run the same risk of interception as with something like TunnelBear, which means that you would NOT use this solution for highly sensitive traffic. Also, I don’t believe that they have all that many servers, so you’d be limited in your choice of where you appear to be. I’ve been meaning to give them a try to see what the service looks like.

[update 7/15/2016] I've installed Private Tunnel for testing. They offer endpoints in: NYC; Chicago; Miami; San Jose; Montreal; London; Amsterdam; Stockholm; Frankfurt; Tokyo; Zurich; and Hong Kong.

I know that’s a long answer! Bottom line is that if you are connecting to someone else’s VPN server, don’t trust it with anything other than mundane traffic. For location-shifting to do something trivial like watch soccer or get around a school’s firewall, commercial solutions like TunnelBear are fine.

Since we’re on the subject, I can’t recall if I mentioned it in class, but if you need secure IM and voice, you (currently) should be using Signal and nothing else. And of course PGP for email :^)

Dogfooding: Defining roles in an MVC architecture with internal APIs

Here's a copy of the talk I did recently at Boston University discussing how to implement a clean MVC architecture for web apps, with a decoupled front end, using an internal API.

Abstract: The architectural design of an application often comes down to a single question: Where is the work done? Traditional client-server applications answer the question unequivocally: On the server. A new class of application, single-page (SPA), has blurred the separation of responsibility by moving data operations closer to the client. This talk discusses an approach that strictly segregates back-end models from front-end SPA views through use of an application-agnostic internal RESTful API, enhancing testability and re-use. While demonstration code will be in Javascript, the approach applies to most client-server application architectures.

Using Javascript Promises to synchronize asynchronous methods

The asynchronous, non-blocking Javascript runtime can be a real challenge for those of us who are used to writing in a synchronous style in languages such as Python of Java. Especially tough is when we need to do several inherently asynchronous things in a particular order...maybe a filter chain...in which the result of a preceding step is used in the next. The typical JS approach is to nest callbacks, but this leads to code that can be hard to maintain.

The following programs illustrate the problem and work toward a solution. In each, the leading comments describe the approach and any issues that it creates. The final solution can be used as a pattern to solve general synchronization problems in Javascript. The formatting options in the BU WordPress editor are a little limited, so you might want to cut and paste each example into your code editor for easier reading.

1. The problem

/*

If you are used to writing procedural code in a language like Python, Java, or C++,

you would expect this code to print step1, step2, step3, and so on. Because Javascript

is non-blocking, this isn't what happens at all. The HTTP requests take time to execute,

and so the JS runtime moves the call to a queue and just keeps going. Once all of the calls on the

main portion of the call stack are complete, an event loop visits each of the completed request()s

in the order they completed and executes their callbacks.

Starting demo

Finished demo

step3: UHub

step2: CNN

step1: KidPub

So what if we need to execute the requests in order, maybe to build up a result from each of them?

*/

var request = require('request');

var step1 = function (req1) {

request(req1, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step1: KidPub');

});

};

var step2 = function (req2) {

request(req2, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step2: CNN');

});

};

var step3 = function(req3) {

request(req3, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step3: UHub');

});

};

console.log('Starting demo');

step1('http://www.kidpub.com');

step2('http://www.cnn.com');

step3('http://universalhub.com');

console.log('Finished demo');

2. Callbacks work just fine, but...

/*

This is the classic way to synchronize things in Javascript using callbacks. When each

request completes, its callback is executed. The callback is still placed in the

event queue, which is why this code prints

Starting demo

Finished demo

step1: BU

step2: CNN

step3: UHub

There's nothing inherently wrong with this approach, however it can lead to what is

called 'callback hell' or the 'pyramid of doom' when the number of synchronized items grows too large.

*/

var request = require('request');

var req1 = 'http://www.bu.edu'; var req2 = 'http://www.cnn.com'; var req3 = 'http://universalhub.com';

var step1 = function () {

request(req1, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step1: BU');

request(req2, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step2: CNN');

request(req3, function(err,resp) {

console.log('step3: UHub');

})

})

});

};

console.log('Starting demo');

step1();

console.log('Finished demo');

3. Promises help solve the problem, but there's a gotcha to watch out for.

/*

One way to avoid callback hell is to use thenables (pronounced THEN-ables), which essentially

implement the callback in a separate function, as described in the Promise/A+ specification.

A Javascript Promise is a value that can be returned that will be filled in or completed at some

future time. Most libraries can be wrapped with a Promise interface, and many implement Promises

natively. In the code here we're using the request-promise library, which wraps the standard HTTP

request library with a Promise interface. The result is code that is much easier to read...an

event happens, THEN another event happes, THEN another and so on.

This might seem like a perfectly reasonable approach, chaining together

calls to external APIs in order to build up a final result.

The problem here is that a Promise is returned by the rp() call in each step...we are

effectively nesting Promises. The code below appears to work, since

it prints the steps on the console in the correct order. However, what's

really happening is that each rp() does NOT complete before moving on to

its console.log(). If we move the console.log() statements inside the callback for

the rp() you'll see them complete out of order, as I've done in step 2. Uncomment the

console.log() and you'll see how it starts to unravel.

*/

var rp = require('request-promise');

var Promise = require('bluebird');

var req1 = 'http://www.bu.edu'; var req2 = 'http://www.cnn.com'; var req3 = 'http://universalhub.com';

function doCalls(message) {

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve(1);

})

.then(function (result) {

rp(req1, function (err, resp) {

});

console.log('step:', result, ' BU ');

return ++result;

})

.then(function (result) {

rp(req2, function (err, resp) {

// console.log('step:', result, ' CNN');

});

console.log('step:', result, ' CNN');

return ++result;

}

)

.then(function (result) {

rp(req3, function (err, resp) {

});

console.log('step:', result, ' UHub');

return ++result;

})

.then(function (result) {

console.log('Ending demo at step ', result);

return;

})

}

doCalls('Starting calls')

.then(function (resolve, reject) {

console.log('Complete');

})

4. Using Promise.resolve to order nested asynchronous calls

/*

Here's the final approach. In this code, each step returns a Promise to the next step, and the

steps run in the expected order, since the promise isn't resolved until

the rp() and its callback are complete. Here we're just manipulating a function variable,

'step', in each step but one can imagine a use case in which each of the calls

would be building up a final result and perhaps storing intermediate data in a db. The

result variable passed into each proceeding then is the result of the rp(), which

would be the HTML page returned by the request.

The advantages of this over the traditional callback method are that it results

in code that's easier to read, and it also simplifies a stepwise process...each step

is very cleanly about whatever that step is intended to do, and then you move

on to the next step.

*/

var rp = require('request-promise');

var Promise = require('bluebird');

var req1 = 'http://www.bu.edu'; var req2 = 'http://www.cnn.com'; var req3 = 'http://universalhub.com';

function doCalls(message) {

var step = 0;

console.log(message);

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve(1);

})

.then(function (result) {

return Promise.resolve(

rp(req1, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step: ', ++step, ' BU ')

})

)

})

.then(function (result) {

return Promise.resolve(

rp(req2, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step: ', ++step, ' CNN');

})

)

}

)

.then(function (result) {

return Promise.resolve(

rp(req3, function (err, resp) {

console.log('step: ', ++step, ' UHub');

})

)

})

.then(function (result) {

console.log('Ending demo ');

return Promise.resolve(step);

})

}

doCalls('Starting calls')

.then(function (steps) {

console.log('Completed in step ', steps);

});

Thinking Outside the App: ExxonMobil and Speedpass+

I'm a big fan of Apple's ApplePay ecosystem, a bit for the convenience of NFC-based transactions, but really for the security. ApplePay is a tokenized payment system in which credit/debit card account information is neither stored on the phone nor transmitted when making a purchase. It seems not a week goes by that we don't read of a data breach at some large retailer.

Gas-station pumps are one of the prime targets for data thieves using skimmers and it make good sense from a security standpoint to enable NFC transactions on them. However, this is a hardware problem...most pumps simply don't have NFC readers, and to retrofit or replace existing pumps, of which there must be hundreds of thousands for each vendor, is prohibitively expensive. Shell Oil is running some trials at a limited number of stations on the west coast, but that's about it, and I don't expect to see NFC pumps anytime soon.

Which brings us to ExxonMobil and their new Speedpass+ iPhone app. The company has long provided what I assume is RFID transactions at their pumps in the form of Speedpass. I don't know if ExxonMobil hired outside talent or developed Speedpass+ in-house, but whoever came up with the idea deserves a big fat bonus. I loaded it onto my phone the moment I head of it (it's free) and had a chance to try it in the field today.

I love it.

So, let's talk about how this was architected.

Here's the problem: You want to offer ApplePay at your service stations, but it's too expensive to outfit the pumps with NFC readers. How else can the problem be solved?

I can almost imagine the meeting. A couple of half-empty pizza boxes on a back table, 2-liter jugs of Mountain Dew. There are some half-finished diagrams on the whiteboard of the existing Speedpass network and data flow. Someone, the person who deserves the bonus, asks the critical question: "Is there some way to do this without using NFC?"

As it turns out, there is. Apple provides an API to enable in-application ApplePay purchases. Once you know that, it isn't a big leap to realizing that you can simply write an app that communicates with the existing Speedpass network. Open the app, tell it where you are, and pay for gas.

But wait, iPhones have GPS radios in them. What if the app could geolocate the user so that they don't have to type in where they are? It's simple enough to build an app that geolocates against a database of stations and their lat/long coordinates.

Next problem. When you use Speedpass, you hold a fob up to the pump, and the pump sends a message to the network to initiate the transaction. The pump self-identifies...how do we know which pump the user is at? Simple, we know which station the user is at via geolocation and a database, so we'll simply include the list of pump numbers in a table, and present the user a list of pump numbers to select from.

Almost there. The app is initiating the transaction, essentially simulating the pump. When you use a Speedpass fob, the transaction is authorized by the back end checking to see if your Speedpass account's payment method is current. here, it's done it the app by calling the ApplePay API...stick your thumb on the phone's fingerprint reader, and the app generates the same sort of authorization token that the pump would have done.

All that's left is to send the authorization signal back to the pump, and the user can buy some gas.

Anyone can write the same old apps that have been done a hundred times before. This is an example of a team really thinking outside their normality to come up with a clever solution just by asking the question, "Is there some way to do this using what we already have?" This is the kind of thinking that separates software engineers from programmers.

Get it: ExxonMobil Speedpass+ for iPhone (free)

Using Postman to test RESTful APIs

There's a sharp divide in MEAN projects between the back end and the front end. Most use cases involve manipulating model data in some way via either a controller or view-controller, which in MEAN is implemented in Angular. The first work to be done, though, is on the back end, defining and implementing the models and the APIs that sit on top of them.

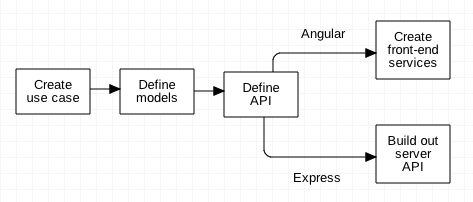

The typical work flow looks something like:

That split is possible because the front end and back end are decoupled; one person can work on the front end and another on the back end once the API has been agreed upon.

There's on tiny problem. How can we test the back end if the front end isn't finished? Let's say you will at some point have a very nice Angular form that lets you create a complex object, and display the results, but it isn't finished, or test requires generating data for multiple views that aren't complete. In these cases we turn to a variety of tools to exercise the back-end API; one of my favorites is Postman, available at getpostman.com.

Postman is essentially a GUI on top of cUrl, a command-line tool that allows us to interact with HTTP services. cUrl isn't too hard to use, but for complex queries it can become a real pain to type everything in the correct order and syntax. Postman takes care of the complexity with a forms-based interface to build, send, and display the results of just about every method you can think of.

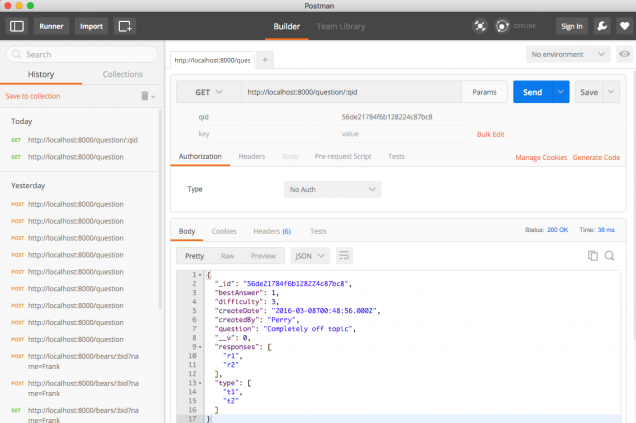

Here's Postman's main interface:

To use it, simply enter the URL of the API you want to test, and enter the appropriate parameters. In the screen shot above I'm doing a GET, passing one parameter, and receiving a JSON object as a result. You can save and edit queries, place queries into tabs, run queries in series, and select an authorization model if you're using one. Also of interest is the 'Generate Code' link which will create code in several languages (Java, Javascript, Node, PHP, Ruby, Python, etc) that you either use directly in your code or include in your test suite.

While Postman and tools like it simplify back-end API development, it's also useful in creating JSON stubs for front-end Angular devs to use for testing until the back end models are fully functional. You can also use it to explore third-party APIs that you might be using...just click Generate Code in the language of your choice to spit out a function to consume the API.

Postman and tools like it solve the chicken-and-egg problem of decoupled development models. It's free, and I think it belongs in every engineer's toolbox.

Why FBI vs Apple is so important

On the face of it, the situation is pretty straightforward: The FBI has an iPhone used by one of the San Bernardino shooters, it is currently locked with a passcode, and they want Apple to assist in unlocking the phone. Apple has stated that they don't have that capability, and that to comply with the order they would have to engineer a custom version of iOS that turns off certain security features, allowing the FBI to brute-force the passcode. It comes down to the federal government forcing a private company to create a product that they wouldn't normally have made.

We can reasonably expect the FBI and Department of Justice to push back on Apple, which has not only provided assistance to the bureau in similar cases in the past, but has also provided assistance in this case in the form of technical advice and data available from iCloud backups. What's interesting about recent events, though, is that they have taken the form of a court order under the authority of the All Writs Act of 1789, which gives federal courts the authority, in certain narrow circumstances, to issue an order that requires the recipient to do whatever it is the court deems necessary to prosecute a case.

Apple has spent months negotiating with the federal government in this matter and requested that the order be issued under seal, which means that it would have in effect been a secret order; the public would not have known about it. It's also a possibility that the order could have been issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a secret court, with no representation for the accused, used by the government to carry out covert surveillance against both foreign and domestic targets. Such an order would have included a gag order precluding Apple from divulging that they had even received it.

Instead, the FBI and DoJ went public with the nuclear option...the All Writs Act. The only reasonable explanation is that they expect this matter to be appealed, and that a federal court will side with the government, setting a landmark precedent. The FBI administrators are not fools; they expect to prevail in this. They picked this specific case, out of all of the similar cases over the past few years, to move their agenda forward.

Apple's position isn't that they can't create a custom version of iOS to accomplish what the FBI wants. It is that to do so would be an invitation to any law enforcement agency to ask for similar orders in any case that came up involving an Apple product. Privacy would be permanently back-doored. And it wouldn't stop with American law enforcement; it isn't a far leap to see China demanding such a tool for Apple to continue to do business in the country.

The defense that Apple (and a growing consortium of supporters, including the EFF) is taking is that both the first and fourth amendments prevent the federal government from compelling speech. In this context, there is legal precedence that computer software is seen as speech, and so Apple cannot be compelled to write code that it doesn't want to create. If the FBI and DoJ were to prevail, they would be able to require any company to write whatever code the government felt necessary, including backdoors or malicious software.

An analogy would be if the government decided that it would be in the public's interest to promote a particular federal program, and so compelled the Boston Globe to write favorable articles about it.

This case has nothing to do with San Bernardino. It has everything to do with the federal government attempting to establish a legal foothold in which individual privacy is at the whim of the courts. And, as Apple has stated, a backdoor swings both ways; it would be only a matter of time before such a tool would be compromised and used by criminals or other governments against us. Privacy is a fundamental right as laid out in the first, third, fourth, fifth, ninth, and fourteenth amendments to the US constitution.

Edward Snowden said, "This is the most important tech case in a decade." The outcome of this case and its appeals will help determine whether our future is one of freedom and privacy or of constant surveillance and a government that can commandeer private companies to do their bidding.

TMO, EFF, and Net Neutrality

I've been watching T-Mobile's new Binge-On (BO) offering for a few weeks now as it gains more and more headlines. Today TMO CEO John Legere went on a rant directed at the Electronic Freedom Foundation (of which I am a member) and their recent analysis of the service.

TMO and Legere say that Binge-On is a feature aimed at providing their customers with a better video experience, and saving them money by not charging data fees for video from Binge-On partners such as Netflix, Hulu, and Youtube. This sounds like a good thing, doesn't it? Free is good.

There are two issues with this. The first is that TMO is slowing down ALL video streams to mobile devices, not just streams from non-BO partners. Every HTML5 video stream is slowed to 1.5Mbps. Some sources are saying that HD video is being converted to 480p, but I haven't seen a definitive answer to this question. Frankly, reducing bandwidth to mobile devices makes a lot of sense, because on those devices a reduced-resolution image looks just fine. If you are watching a video on a 5-inch screen, you really don't need to see that stream in high-bandwidth, high-resolution. You can opt out of Binge-On, and that's really what has folks in a dither...it's turned on by default. TMO counters by pointing out that customers were inadvertently burning through their data plan by watching unnecessarily high bandwidth video.

The second, and larger issue, is net neutrality. In 2015 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued a ruling that basically said that data is data...it's illegal to differentiate among and treat differently email versus text versus video versus web browsing. TMO's Binge-On is in direct violation of this, treating video differently than other network traffic. Worse, the Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF) showed that TMO slowed down video traffic even when the file was not explicitly identified as video (with a .mpg file extension, for example). That means that TMO is peering inside the data to see what it is...a technique called deep packet inspection. If TMO is inspecting packets, what else are they planning on doing? And who are they sharing that information with?

I'm of two minds on this issue. I'm a proponent of net neutrality, and I find it offensive that TMO is treating different kinds of data traffic in different ways. Net neutrality was hard-fought and extremely important in protecting the free exchange of ideas on the internet. As a consumer, though (and I use TMO on a tablet for audio streaming), how can I argue against free? I specifically bought a TMO tablet so that I could stream music at no charge through their Music Freedom program.

I've asked the EFF about Music Freedom and if its the same technique as Binge-On (deep packet inspection). No one complained about MF when it was launched a year ago. I have to think that TMO's competitors are lining up their lawyers to take this one to the mat. I think that my position has to be with net neutrality...it is so much more important than a bunch of TMO subscribers getting free video.