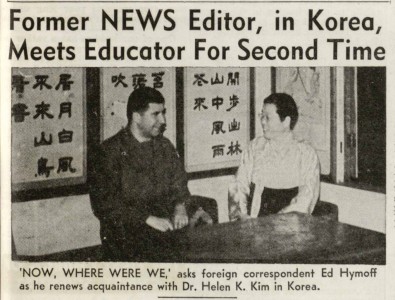

Kim Hwal-lan (Kim Helen) and Ed Hymoff

In the twentieth century, both Korea and the United States emerged to new positions in the world. Korea was liberated from Japanese occupation to become two countries divided along the 38th parallel. The United States came out of World War II a dominant world power that constructed a new international order designed to contain Communist regimes around the world, including North Korea. With the outbreak of war in Korea in 1950, the lives of many Koreans and Americans and the histories of their nations became closely linked. Ties between Korea and America were not built only on geopolitical developments, however. Bonds were also built by Christian missionaries, educational institutions, professional relationships, and personal history, as illustrated in the story of this photo depicting the meeting of two Boston University alumni, a Korean woman named Kim Hwal-lan (Kim Helen) and an American man named Edward Hymoff.

Kim Hwal-lan (Kim Helen, 1899–1970) was one of the most influential female leaders in twentieth-century Korea.[1] She was an educator, stateswoman, churchwoman, and feminist intellectual. She was a leading figure in the New Women’s movement—a movement that rejected the traditional Korean Confucian role of women and advocated gender equality. In the 1920s and 1930s, Kim was a founding member (and later the president) of the Korean YWCA, and she strove to promote equal rights and opportunities for Korean women. She served as professor, dean, and the first Korean president of Ewha Womans University, one of Korea's oldest universities, founded by American Methodist missionary Mary F. Scranton in 1886.[2] Throughout her career, Dr. Kim's remarkable talents and leadership in areas such as women’s education, politics, diplomacy, and the Christian church offered a new model of womanhood during Korea's modernization.[3]

Today, Dr. Kim is considered one of the most controversial Korean intellectuals of the twentieth century because of her collaboration with the Japanese colonial powers during World War II.[4] She justified her actions as necessary in order to keep Ewha open under harsh colonial policies.[5] Her actions were also consistent with the missionary policy of the Methodist church that sought to minimize conflict with colonial authorities. Thus, the life and work of Dr. Kim reflects the complicated history of Korean women in the face of traditional patriarchal gender norms, as well as oppressive Japanese colonial authority.[6]

As a child, Kim was educated in church-related schools, and she came to the United States for her higher education with the support of American women missionaries in Korea who frequently arranged for promising students to study in the U.S.[7] Her study in the U.S. was also sponsored by Jeannette Walter, interim president of Ewha College, and Herbert Welch, American Methodist Bishop and missionary to Korea from 1916 to 1928.[8] Kim earned a B.A. from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1924 and an M.A. from Boston University Graduate School in 1925.[9] In 1931, she received a Ph.D. from Teachers College of Columbia University with a dissertation entitled “Rural Education for the Regeneration of Korea.” This made her the first Korean woman to receive a doctorate.[10] After returning to Korea, Dr. Kim was appointed the president of Ewha College in 1939 and of Ewha Womans University in 1945. She served in that capacity until 1961. Under her presidency, Ewha became the largest women’s university in Asia.[11]

The contributions of Dr. Kim were not limited to the field of higher education in Korea. She attended over fifty international conferences as a Korean delegate and speaker, including the International Missionary Council and the World Council of Churches.[12] Dr. Kim was also selected by Korean President Rhee Syngman (Yi Seung Man) in 1948 to serve as a Korean delegate to the United Nations General Assembly Meeting. In addition, she became president of the daily English-language newspaper, The Korea Times, in 1952, and vice-president of the Korean Red Cross in 1955. Dr. Kim later received five honorary doctorates from prestigious universities, including Boston University School of Law.[13] She died in 1971, after dedicating her life to the advancement of women’s issues in Korea.[14]

While Kim was in the United States to attend the U.N. General Assembly in 1949, the Boston University student newspaper, Boston University News, sent Ed Hymoff to New York to interview her for a story to run in conjunction with her honorary doctorate from Boston University. That story evidently never ran in print. That meeting, however, created a relationship between Kim and Hymoff that would be rekindled several years later.[15]

A native of Boston, Ed Hymoff (1924-1992) was drafted into the U.S. Army shortly after his eighteenth birthday in 1943.[16] During his Army training, he was identified as a potential candidate for service in the Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.), the American intelligence agency created during World War II. In the final years of that war, Hymoff was stationed in Italy, where he helped to supply Marshal Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslav resistance forces.[17] After his discharge, Hymoff returned to Boston and enrolled as a student in Boston University. He graduated in 1949 from the School of Public Relations.[18]

His first professional job was as a reporter at the city desk of New York’s World-Telegram & Sun, but when war broke out in Korea in 1950, Hymoff went to that country as a war correspondent. In that capacity, he sent dispatches on the war to several newspapers throughout New England and reported to his college newspaper of his reunion with Dr. Kim.[19]

Over the course of his life, Hymoff wrote many books. Several of these highlighted different aspects of growing American power in the late twentieth century. With Martin Caidin, he wrote a book, The Mission, that told of a secret combat mission that then Congressman (and future President) Lyndon B. Johnson flew during World War II. Another work reported on operations of the O.S.S. during World War II. In the 1960s and 1970s, when American engagement in Vietnam escalated, Hymoff again became a war correspondent and wrote four books about the Vietnam war, each highlighting a different division of American forces there. He edited a book on the Kennedy family with Phil Hirsch, and wrote another book on the American space program.

Based on his early experience with espionage in the O.S.S., Hymoff maintained an ongoing, but critical interest in similar operations throughout the Cold War.[20] He believed that American strategic operations during the Korean War, such as an attempt to land covert forces behind North Korean lines, failed because they did not draw on the expertise of O.S.S. veterans or learn lessons from similar operations during World War II.[21] During armistice talks in Korea, the Central Intelligence Agency (C.I.A.) even asked Hymoff to offer the Australian journalist and Soviet agent Wilfred Burchett $100,000 to defect to the West. Burchett had developed close ties to North Korean Communists that the C.I.A. thought would be valuable. Hymoff argued that Burchett could not be won over, and his judgement proved to be correct.[22]

As a media executive with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, he was instrumental in developing the satellite system used for radio and television broadcasts. With NBC News, he helped create a Peabody award winning radio program, “Monitor,” and in 1980, he worked with the League of Women Voters to produce the 1980 Presidential debates between President Jimmy Carter and future-President Ronald Reagan. He died at his home in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Citations

[1] Choe Hye-Wol, Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea: New Women, Old Ways (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 149.

[2] “The History of Ewha Womans University,” Ewha Womans University. http://www.ewha.ac.kr/kor/intro/index.jsp?doc=1_4_2_2_1 (accessed on March 15, 2013)

[3] Ihwa Yoksagwan, Ewha Old and New: 110 Years of History, 1886–1996 (Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press, 2005), 44.

[4] Choe, Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea, 149.

[5] Ibid., 151.

[6] Ibid., 154.

[7] Dana L. Robert, “The Influence of American Missionary Women on the World Back Home,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 12 (2002): 77.

[8] Helen Kim, Grace Sufficient: The Story of Helen Kim by Herself (Nashville: The Upper Room, 1964), 50–51.

[9] Ibid., v.

[10] Ok Jun-Chae, “Kim, Helen,” in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, ed. Gerald Anderson (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998), 364.

[11] Ok Jun-Chae, “Kim, Helen,” 364.

[12] Ok Jun-Chae, “Kim, Helen,” 364.

[13] Ibid., 364.

[14] Choe, Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea, 152.

[15] "Former NEWS Editor, in Korea, Meets Educator for Second Time," Boston University News, April 29, 1952.

[16] "Edward Hymoff," National Archives and Records Administration. U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946, in Ancestry.com, http://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?rank=1&new=1&MSAV=0&msT=1&gss=angs-i&gsfn=edward&gsln=hymoff&uidh=ibd&db=WWIIenlist&indiv=1&pf=1&recid=&h=6214658&fh=&ct=&fsk=&bsk= (accessed March 2, 2013).

[17] Edward Hymoff, The OSS in World War II, revised and updated ed. (New York: Richardson & Steirman, 1986), 1-13.

[18] 1949 Hub: Senior Annual of Boston University, Vol. XIX. (Boston: n.p., 1949), 112.

[19] "Former NEWS Editor"; "Edward Hymoff Dies; Media Executive, 67," New York Times, July 11, 1992, http://www.nytimes.com/1992/07/11/obituaries/edward-hymoff-dies-media-executive-67.html (accessed March 26, 2013).

[20] Ed Hymoff, "Trouble for Communists: Small Change Fights for Freedom in Red Backyard," Daily Boston Globe, December 6, 1951.

[21] Hymoff, The OSS in World War II, 16, 374-5.

[22] John M. Crewdson, "C.I.A. Established Many Links To Journalists in U.S. and Abroad; C.I.A.'s Numerous Links With Journalists Differed Widely in Degree and Value," New York Times, December 27, 1977.

[23] "Edward Hymoff Dies."

Written by: Daewon Moon and Doug Tzan

Edited by: Doug Tzan