Pak Bong-rang

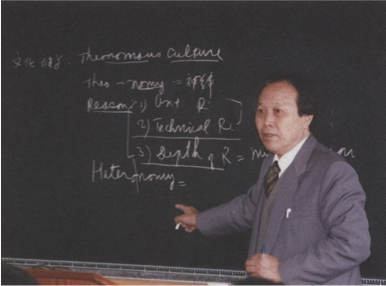

Gohwa Pak Bong-rang was a first-generation scholar, who, drawing on his diasporic experience in Boston, contributed to the development of theological thought in Korea. In the midst of Korea’s historic upheavals Pak introduced John Calvin’s Reformed theology, Karl Barth’s theology of God’s Word, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s evangelical theology of practice, and secular theology. Pak, along with Jeon Gyeong-yeon, was one of the greatest figures in the academically impoverished Korean theological circles. He was especially focused on modern systematic theology and Dogmatics in Reformed tradition.

Gohwa Pak Bong-rang was a first-generation scholar, who, drawing on his diasporic experience in Boston, contributed to the development of theological thought in Korea. In the midst of Korea’s historic upheavals Pak introduced John Calvin’s Reformed theology, Karl Barth’s theology of God’s Word, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s evangelical theology of practice, and secular theology. Pak, along with Jeon Gyeong-yeon, was one of the greatest figures in the academically impoverished Korean theological circles. He was especially focused on modern systematic theology and Dogmatics in Reformed tradition.

He was born on September 3, 1918 in Sinyang-ri 8, Pyeongyang, to Pak Yeong-seol and Kim Jeong-seol as the second child between one elder sister and one younger sister who survived among their seven sons and three daughters. His father received the gospel in his early childhood, became an elder of a church, and later planted Chuja-do church in Pyeongyang. His mother was also a devout Christian who served the church as an elder.[1] Pak learned the Christian faith through Sunday worship, prayer, and Bible recitation under the influence of his parents. In the meantime, two life-changing events occurred to him, that is, his elder sister and his father suddenly passed away.[2] Pak Bong-rang recalled, “because of these two existential experiences, I was able to participate easily in the theological discussions of the 1960s and 1970s, especially after Bonhoeffer, revolving around theology of crucifixion, theology of eschatological hope, and liberation theology.”[3]

Pak left his home with his mother and younger sister and moved near Sungsil School in Pyeongyang (a 5-year school established by the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, equivalent to today’s middle-high school). There he spent his boyhood, attending Seomunbak church.[4] When Bak was in third year in the school, he heard a sermon from a Presbyterian missionary and decided to become a pastor with his friends, Yu Eung-gi and Yi Yeong-heon. He read various literary works, and prayed hard to become a powerful preacher.[5]

After his graduation from Sungsil School in 1937, Pak Bong-rang married Kang Deok-sil at the age of 19, with whom had had four sons and one daughter. Though he tried to find a way to study theology, his burning desire to become a pastor was frustrated because Pyeongyang Theological Seminary, the only theological seminary in Korea, was closed by the Japanese Government General of Korea.[6] Bak served as a teacher in a Bible Study club of a rural church which was run by the subsidy of the Presbyterian Mission Agency and he was responsible for preaching on Wednesday and Sunday evenings. Meanwhile, Pak decided to study in Japan after consultation with Yu Eung-gi, who had come home for a summer break while studying in Japan. In the summer of 1938, he left to study in Tokyo despite the protests of his mother and wife.[7]

Tokyo had four seminaries: Japan Theological Seminary, Cheongsan Academy, Ipkyo University Seminary (Anglican) and Lutheran Seminary. Pak entered Japan Theological Seminary because it was directly run by the Japanese Presbyterian Church. The Japanese Seminary was a five-year college consisting of two years of preparatory courses and three years of the regular course.[8] During the first two years of his studies, he gained a considerable degree of proficiency in German, Hebrew, and Greek, and explored various theological perspectives, especially that of Karl Barth. Pak Bong-rang confessed that he was not unfamiliar with Barth’s theology because of his Presbyterian background.[9] During his study, the Second World War broke out in 1939 and Japan caused the Pacific War in 1941.

Pak Bong-rang, who depended on money from his mother and wife to study, felt responsibility for his family, stopped in the middle of his schooling and returned home. After serving as a teacher for 2 years at an elementary school to fund his education, he went back to the seminary where he rejoined Yi Yeong-heon, his friend from Sungsil School, and Jeon Gyeong-yeon, who became his lifelong academic fellow.[10]

In 1943, Pak returned home temporarily during the summer break because his health deteriorated. Before long, he was mistaken as a thought criminal (who resisted Japanese colonial rule of Korea) and was arrested by a Japanese police officer. He spent nine months in the jail in Pyeungwon. As Japan neared defeat the oppression of Koreans worsened. Pak Bong-rang moved his dwelling to Pyeongyang and waited for the liberation of Korea while he taught at Gwangmyeong School for the blind in Seojangdae.[11]

After liberation, the Korean Peninsula was divided into the south and the north based on the 38th parallel. Pak Bong-rang was in charge of the evangelism of Seomunbak church at the end of 1946. However, in order to continue his study, he went to the south, crossing the 38th parallel in May 1947. While serving Sungdong church in Seoul and teaching as a German teacher at Gyeongsin High School, he transferred to the graduate class of Joseon Theological Seminary (Korea Theology College) in September 1947. In the daytime, Pak studied theology and at night, he taught English and German at Gyeongseong Electric Technical High School. With his credits in Japan Theological Seminary transferred, he was able to graduate Joseon Theological Seminary in 1948. He became a full-time lecturer at the seminary from 1949 to 1952.[12]

In 1950, Joseon Theological Seminary was evacuated to Busan due to the Korean War and functioned with a tent campus under the leadership of Kim Jae-jun, the dean of the seminary. During this period, Pak Bong-rang received a full scholarship from Asbury Theological Seminary in Kentucky. It included round-trip travel expenses, tuition and a stipend. At first, he was hesitant to study abroad because of the difficulty of leaving his refugee family who had no guarantees of life, but he decided to leave because of Kim Jae-jun and many others’ strong encouragement.[13] Later, reflecting on his move to Wilmore, Kentucky, he noted that “My theological life was like a wanderer taking down the tent over and over again. It was the history of decision and adventure…What made this adventure possible? God has put me in the situations, which are inevitable. These situations can be regarded as God’s calling…”[14]

adventure possible? God has put me in the situations, which are inevitable. These situations can be regarded as God’s calling…”[14]

Pak sent most Asbury’s financial support to Korea, while he did various part-time jobs. He focused on the practices of ministry, including sermon composition, hymnology, Christian education, preaching, and sermon criticism. Everything he learned was inflected by the seminary’s Arminianism, John Wesley’s holism, and biblical inspiration. He also devoted himself to studying Hebrew and Greek in hopes of further graduate school education.

Pak graduated from Asbury Theological Seminary in 1954, and later that year entered the master’s program at Harvard Divinity School.[15] At Harvard he was especially fascinated by Paul Tillich’s lectures, and attended his classes on theological methodology, theology, Christology, and biblical theology. When he earned his Master’s degree in sacred theology (S.T.M.) in 1955, he also gained admission to Harvard’s doctoral program with full tuition and a stipend. Once again, Pak sent most of the money to Korea while he worked in the graduate school kitchen and over the summers to pay for his expenses.[16]

During his busy school days in Boston, he also served the First Korean Church of Boston as the second senior pastor from 1955 to 1957.[17] Harvard credited his Master’s degree, which allowed Pak to finish his doctoral coursework in the first year, and take the language examination and comprehensive examination in systematic theology the second year. In order to focus on his dissertation, he stepped down from his position in the church, and began working with Paul Lehmann—a prominent Barthian scholar who came to Harvard in 1956. In 1958, he was awarded a doctorate in theology (Th.D.) after submitting his dissertation titled “Karl Barth’s Doctrine of Inspiration of the Holy Scripture with Special Reference to the Evangelical Churches in Korea.”[18]

After returning from the United States in September 1958, Pak Bong-rang served as an assistant professor and associate professor at Korea Theology College until February 1964. However, he had to move to Konkuk University in March 1964 due to political instability and served there as a professor and student director for five years until February 1969. In March 1969, he was reinstated in Korea Theology College and taught there until his retirement in February 1984.[19] While teaching there, Pak spent a year as a research professor at the University of Tübingen in Germany in 1973. He was also a professor of systematic theology at United Graduate School of Theology in Yonsei University from its opening in the 1960s.

Gim Jaejin characterizes Pak’s theology as “the theology of action that embodies the testimony of the Bible, God’s Word.”[20] Pak Bong-rang said, “What I was trying to teach was evangelical dogmatics. It is…the theology of the Word of God represented by Calvin, Barth, and Emil Brunner…that is, the theology of God’s grace and/or evangelical theology.”[21] Through his numerous theological books and papers, Pak has contributed greatly to Korean theological circles by extensively introducing not only Barth’s theology, but also the theologies of other modern theologians, even as he interpreted them from his Barthian perspective.[22] For example, he stood with Jeon Gyeong-yeon, as Korea’s two preeminent Barthians, and debated with Yun Seongbeom about the indigenization of Christian gospel.[23]

During his career the political situation radically changed, first because of the 4.19 student revolution in 1960, then again because of the 5.16 military coup in 1961 and the ensuing military dictatorship. The theological situation was also altered following the debate over the secular theology after 1960. In changing circumstances, Pak Bong-rang sought out a theological interpretation of the situation. He found a valuable resource in the theology of action of the young theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who resisted Adolf Hitler, the German dictator.[24] In the midst of Korea’s socio-political upheaval, Pak published a book in 1976 entitled The Religionless Christianity, a study on Bonhoeffer’s theology. It aimed to help the Korean church be faithful to the nature of the gospel and to answer the urgent problems of the times. This book, the first theological book on Bonhoeffer written by a Korean and in Korean, illuminated Bonhoeffer’s theology of action.[25] Before long, it became the most widely read theological book for college students, seminary students and young pastors who longed for democracy during the military regime and cried for human rights and freedom of speech.[26] Though Pak did not appear at the forefront of the struggle for democracy, he played a crucial role in transplanting Bonhoeffer’s theology and life into the Korean church and larger society, and providing direction for the resistance movement.[27]

Park Chung-hee’s military regime, noting that Pak’s book was widely read, made the author a person of interest. As a result, when the board of Korea Theology College decrided to appoint Pak Bong-rang as a new dean of the school and sent his recommendation to the ministry of education, it was rejected. Moreover, the school was forced to fire him if it did not withdraw the recommendation. In the end, he served Korea Theology College as a professor without any promotion until his retirement.[28]

Pak and Jeon Gyeong-yeon took a critical stance toward Minjung theology. Nevertheless, he did not criticize it through lectures or writings, because he was positive about its interest in people’s liberation in the present context.[29] His concern was that God should be the subject of history in order for people to be liberated. Therefore, he was very critical of the theory of Minjung Messiah or Minjung Subject. He also doubted that the specificity of Christianity was relativized by a certain context and/or contextual theology, which would raise a context above the biblical text.[30]

took a critical stance toward Minjung theology. Nevertheless, he did not criticize it through lectures or writings, because he was positive about its interest in people’s liberation in the present context.[29] His concern was that God should be the subject of history in order for people to be liberated. Therefore, he was very critical of the theory of Minjung Messiah or Minjung Subject. He also doubted that the specificity of Christianity was relativized by a certain context and/or contextual theology, which would raise a context above the biblical text.[30]

Pak debated the theological ideas of Bultmann, Brunner, Tillich, and Reinhold Niebuhr from the perspective of Barth. Moreover, he introduced into theological discussions the relationship between culture and life in Christian social ethics amidst the death of God theology by publishing a large volume book (789 pages) titled The Secularization of God. Published in 1983, the tome engaged Thomas Altizer (Christological atheism), Robert Brown (Bultmannian), Helmut Gollwitzer (Barthian), Wolfhart Pannenberg (historical approach to theology), Jürgen Moltmann (theology of hope), Dorothee Sölle (political theology), and Eberhard Jüngel.[31]

Pak Bong-rang helped to lay the foundation of the Korean theology by publishing several masterpieces, including Methodology of Dogmatics vol. 1 (1986), vol. 2 (1987), The Liberation of Theology, which dealt extensively with the theology of hope, political theology, liberation theology, and Minjung theology (1991), and Theology of Eschatology which was written as he struggled with being sick, and was published three days before his death (2001). He also translated Barth’s major works through Jeon Gyeong-yeon’s Evangelical Theology Series and Moltmann’s Theology of Hope and The Church in the power of the Holy Spirit: Messianic ecclesiology. In addition, he wrote 131 academic articles.

Pak never left church ministry during his life. As described above, he tried to strengthen a community of faith wherever he was, as he served the First Korean Church of Boston during his time in Boston. After returning to Korea, he attended Seongbuk Church, which was planted by Jeon and later served as its senior pastor from 1966 to 1968. Beginning in 1970, he served Sudo church as a preacher for three years. Always maintaining a close relationship with the field of ministry, Bak was a representative of Korea at the World Alliance of Reformed Churches Assemblies in 1970 (Nairobi, Kenya), 1982 (Ottawa, Canada), and 1989 (Seoul, Korea).

After his retirement in 1984, he taught at Hansin University as a professor emeritus and established the Karl Barth Soc iety in Korea. He also translated all the volumes of Barth’s Church Dogmatics. After his lonely and long journey as a pastor and a theologian, Pak Bong-rang passed away on April 25, 2001 due to a chronic disease. Later, the pastors who sincerely loved and respected the deceased dedicated the title Gohwa (which means the one who bore suffering) to him.

iety in Korea. He also translated all the volumes of Barth’s Church Dogmatics. After his lonely and long journey as a pastor and a theologian, Pak Bong-rang passed away on April 25, 2001 due to a chronic disease. Later, the pastors who sincerely loved and respected the deceased dedicated the title Gohwa (which means the one who bore suffering) to him.

Pak Bong-rang was a theologian who introduced new theological trends to the Korean church. He recalled, “Because there was no theological foundation at all, it was crucial to introduce the theological trends of the world in order to establish the theological tradition of the Korean church. I was convinced that it was the task that was required to present the direction for the mission of the church in midst of a rapidly changing modern society.”[32]

Kim Gyun-jin summarizes the contribution of Pak Bong-rang to the Korean theology as follows: First, Pak Bong-rang introduced academic theology and academic objectivity into the Korean theological circles.[33] Second, by introducing Barth’s theology as well as modern liberal theology of the 20th century, he contributed to the restoration of theological freedom from fundamentalism’s theological standardization and clericalism.[34] Third, Bak improved the level of the Korean theological discourse by ensuring that Korean theology by Korean theologians could interact with theologians around the world.[35] Fourth, under the influence of Barth, he served as a theologian of the Church throughout his life. “His contribution is to illuminate that theology should be grounded on the existential faith of a theologian that comes from one’s own religious decisions and confessions in order to faithfully serve the church.”[36]

According to the testimonies of his students, Pak was always free from avarice living a life of honest poverty and sharing what he had with the others. They recalled him as the one who poured all his heart and soul into theology and was kind, meek, and humble, a true disciple of Jesus Christ. Along with Jeon Gyeong-yeon, Pak was one of the roots of the Korean Presbyterian Church and Korean academic theology.

According to the testimonies of his students, Pak was always free from avarice living a life of honest poverty and sharing what he had with the others. They recalled him as the one who poured all his heart and soul into theology and was kind, meek, and humble, a true disciple of Jesus Christ. Along with Jeon Gyeong-yeon, Pak was one of the roots of the Korean Presbyterian Church and Korean academic theology.

Written by Duse Lee

[1] Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 187.

[2] Bongrang Bak, “Naui saeng-aewa sinhag [My Life and Theology],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 28-30.

[3] Ibid., 31.

[4] Ibid., 32; Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” 189-190.

[5] Ibid., 190.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Bongrang Bak, “Naui saeng-aewa sinhag [My Life and Theology],” 35.

[8] Ibid., 36.

[9] Ibid., 39; Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” 194-196.

[10] Bongrang Bak, “Naui saeng-aewa sinhag [My Life and Theology],” 42.

[11] Ibid., 43-44.

[12] Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” 193-198.

[13] Bongrang Bak, “Naui saeng-aewa sinhag [My Life and Theology],” 52-54.

[14] Ibid., 54-55.

[15] Ibid., 56-57.

[16] Ibid., 59-60.

[17] See the article on the First Korean Church of Boston at http://sites.bu.edu/koreandiaspora/institutions/first-korean-church-of-boston/.

[18] Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” 199.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., 200.

[21] Bongrang Bak, “Jojigsinhaggwa na [Systematic Theology and I],” Sinhag-yeongu [Theological Studies] 31, (April 1990): 21.

[22] Jaejin Gim, “Gohwa Bak Bongrang bagsaui sinhagpyeonlyeog [Gohwa Dr. Bongrang Bak’s Theological Journey],” 203.

[23] Ibid., 204.

[24] Ibid., 205.

[25] Seokseong Yu, “Dogsinhohag-ui Bak Bongrang gyosunim [Professor Bongrang Bak, A Man of Faith and Learning],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 370.

[26] Yeongseok O, “Eunsa Bak Bongrang gyosunimgwa nawaui gwangye [The Relationship Between My Mentor Professor Bongrang Bak and Me],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 310.

[27] Giyeong Yi, “Hangug janglogyo sinhag hyeongseong-ui gongloja Bak Bongrang bagsanim [Dr. Bongrang Bak, The Contributor for the Formation of the Korean Presbyterian Theology],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 317-318.

[28] Yeongseok O, “Gidoggyoui bijong-gyohwaui jaejomyeong – Oneul-ui hangugjeog sinhaggyewa gyohoeui hyeogsin-eul wihayeo [Review on The Religionless Christianity – For the Transformation of the Korean Theological Circles and Churches],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 120-121.

[29] Gwonmo Jeong, “Bak Bongrang seonsaengnim-ui sinhagjeog moghoelon I, II [Bak Bongrang’s Theological Ministry I , II],” in Moghoejaui majimag jeung-eon [The Last Testimony of the Pastor], ed. Jinhan Seo (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 2016), 211.

[30] Ibid., 212.

[31] Gyunjin Gim, “Die theologische Peregrinatio von Prof. Pong-Nang Park – Ihre geschichtliche Bedeutung im Zusammenhang mit der Spaltung der presbyterianischen Kirche von Korea in 1950er Jahren,” Sinhag-yeongu [Theological Studies] 57, (December 2011): 58.

[32] Bongrang Bak, Sinhag-ui haebang [The Liberation of Theology] (Seoul: The Christian Literature Society of Korea, 1991), 27.

[33] Gyunjin Gim, “Die theologische Peregrinatio von Prof. Pong-Nang Park – Ihre geschichtliche Bedeutung im Zusammenhang mit der Spaltung der presbyterianischen Kirche von Korea in 1950er Jahren,” 60.

[34] Ibid., 61.

[35] Ibid., 62.

[36] Ibid., 62-63.