One-Hundred-Twenty Acres, Not Forty Acres and a Mule

J. MOFFETT WALKER

Retired Teacher / Counselor

Freelance Writer & Author

Do you think a Mississippi slave descendent has an intriguing family history? If so, where can one find a descendent to make such a claim? I know the answer. I live this history every day; and it is the story of my ancestors. I am a relative of the late Elisa and Jennie Turner, their son, Harry, and his wife, Martha, who lived it and left this unique legacy. I own copies of the documents to support this interesting past, and I relish sharing my documented history.

These documents tell me more than what one usually finds when examining slaves’ family history. They show me why it was important that at least one family of slave holders held on to their slaves. The documents may suggest some of us slave descendants might be geographically closer to our ancestors than we think. And my documented history shows what local or family records can reveal about slavery and war.

Actually, this historical research started when Alex Haley, author of Roots, inspired and motivated African Americans to begin searching for their ancestors. After watching the show, a cousin and retired teacher in Los Angles, California, the late Alfonzo Turner, collected, published and shared the historical documents he had received directly from the John Wells family. The Wells family owned the Bethesda Plantation.

Before Cousin Alfonzo’s inspiration, fewer Black people attempted to research their past. Numerous road blocks prevented people from digging into their roots or backgrounds. But the Turner family’s history proved differently.

I have copies of documents showing the following transactions:

“A deed from Robert Wells to my grandfather, Thomas Wells, dated April 24, 1832, conveying Harry Turner to my grandfather; Robert Wells was a brother of Thomas Wells and a neighbor in this county. In 1839 Robert Wells moved to Arkansas and died there shortly thereafter.” 1

“A bill of sale from Dewitt and Barnes, slave merchants, dated November 14, 1835, to Thomas Wells conveying two slaves, one of whom was Martha, later wife of Harry Turner. She was fifteen years of age at the time of the conveyance.” 2

Since my ancestors, the Turners, remained with the Wells family for decades, I have access to records written by Dr. John Wells about the Turners. For example, in 1803 Dr. John Wells wrote notes about his family and included information about my great-great-great-great grandmother, Jennie Wells Turner, who lived to be about seventy-two years old.

Records show she was ten years old when she moved from South Carolina to Mississippi with Nathaniel Wells, his family, and four other slaves. They settled in Pike County, a small town located near Summit, Mississippi.

“Harry Turner’s father belonged to a man named Edward Turner, who owned a plantation in Pike County and partly in Amite Counties (County). Edward was a man of some prominence during the Territorial Days prior to 1817, when Mississippi was admitted to the Union.” 3

“When Nathaniel Wells and his wife Elizabeth Simmons Wells [,] moved from South Carolina to Mississippi in 1803, they ‘bought’ [brought] 5 slaves with then. One of these was Harry’s mother Jennie, then a girl. It was in Pike County that Harry was born in 1817.” 4

I was so interested when I read the information about Pike County. I taught school at Burgland High School in McComb, Mississippi, from September 1961 to May 1962. I did not know about this family history or that there was a family connection near the school. I may have taught some relatives. Who knows?

I was also interested to learn from these how my family acquired the name Turner.

“Harry took as his surname when he was emancipated [,] the name Turner.” 5

Dr. John Wells, W. Calvin Wells’ father, recorded these family notes:

“Harry was the most valuable slave my father ever owned. He was born a slave of my great-grandfather, Nathaniel Wells, 1717-1884, ([A] major under Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans)[,] and by him given to my uncle, Robert Wells, who kept him some years and sold him to my father, Thomas Wells.” 6

“He was the oldest son and second child of old Grand Mammy Jennie who was sold in 1844, after my grandfather’s death, she was appraised at nothing and my father took her and supported her until she died in 1864 or 1865.” 7

In his memoir, Cousin Alfonso Turner stated, “My great-grandmother, Jennie Wells, was born in 1793 [,] the same year of the invention of the cotton gin in America.” 8

This information suggests Thomas Wells was a man who showed concern for others. He respected the elderly. I believe he saw slaves as real people and not as lower animals as some other slave owners did and as was proved by these owners’ actions. I believe Thomas Wells listened to his conscious and his heart. A plantation document indicated Thomas dealt with Harry as one man to another. I am unsure exactly what I mean by that, as one was master and the other a slave, but I do believe Thomas showed some empathy for Harry. Thomas Wells could have allowed old Grand Mammy Jennie to die by refusing to assist her. Or he could have sent her to another family. He could have assisted her in crossing over into eternity and there would have been no repercussions for him. Instead, he cared for her. The Wells also erected headstones of Elisa Turner and Grand Mammy Jennie Turner at Bethesda Church Cemetery, located on Canada-Cross Road, Edwards, Mississippi.

When I use the term “family circle” in this essay, what I mean is that the Wells sold their slaves only to other Wells family members. This was beneficial for the Wells, because it meant they knew their slaves were healthy, trustworthy, and responsible.

The fact that the Wells kept slaves in the “family circle” meant something else, perhaps something more significant, to the Turners. I believe the Turner family was relieved the Wells kept the Turner slaves in close proximity; I believe this made the Turners happier, and it probably helped to develop and maintain trust between masters and slaves. It meant the Turners did not live with the horrible fear other slaves did of being separated from spouses, children, siblings, parents or grandparents. For contemporary Turners such as me, it makes researching the past easier.

When I consider what I am calling the “family circle,” the relationships between the families, and the work done by both families, I have to consider the history of the 1800s and the period’s social class system. The idea of a “family circle” did not mean the same thing then as it does now. We have to understand this distinction in order to understand the family history I am discussing.

In the 19th century, female slaves worked outside the home in the Big House; they cleaned, cooked, and cared for the children. Most female slaves worked in the fields. On the other hand, most white females did not work at all and few if any worked in the fields. The white men took care of the women economically. In contrast, slave men were in servitude and did not have the opportunity to provide economically for their families. Today, most females work; some need the income to support their families.

Records show the Wells kept a workable “relationship” with the Turners. I believe the Turners received no beatings or hangings, and it seems they did not have to worry about their females being raped.

I had to learn to accept the titles, such as “grand mammy” and “uncle” and “aunt,” that were placed before slave names. Those titles could have meant respect in the 19th century, but during my childhood years and during Separate-but-Equal times, the terms meant disrespect. Colored people considered these titles as an opportunity for white people not to address slaves as Mr. or Mrs.

Thomas followed his ancestors’ tradition and kept the Turners within the “family circle.” He also deeded Harry valuable land. I believe the Turners received better treatment than most slaves on other plantations did. Records support my position. Yet, I must be realistic. The Turners were slaves; they were not free. The only way I can understand these seemingly contradictory things is to realize in order to comprehend the Wells’ and the Turners’ life styles, I cannot judge them through my history. They lived through slavery, and I lived through Separate-but Equal.

All the documents I have mentioned are significant to me. These documents and others that I will discuss will prove that the Wells did own slaves but also they kept the Turners within their “family circle” for decades. I cannot explain how much these documents mean to me. If the Wells had not shared these documents, the Turner family would not have known about our rich slave legacy. I know I am fortunate to have copies of the documents.

I see the “relationship” between the families as noteworthy within the context of slavery as well. What the Wells did gave me the opportunity to document nine generations, from Elisa and Jennie Turner to my great-grandsons Cam’ron Walker Baker and Keith Baker III. Furthermore, the “relationship” established between the Wells and Turners remained in place until Harry’s death and afterward. I say afterward, because I have included in this essay quotations which show how the Wells family carried out Harry’s wishes.

By the mid-1800s national developments were apparent to slave owners. Conflicts within the Union had been brewing and escalating for some time, but the issues became non-negotiable. The Southern states succeeded from the Union and formed the Confederacy with Mississippi joining the ranks on January 9, 1861. Soon after that the War Between the States began. In the 21st century some individuals question the reasons for the war. I understand slavery and the slave economy was one of the reasons, probably the main reason, in the South. Although the Northern states did not base their economy primarily on free slave labor, some Northern individuals owned slaves and some institutions profited. Slaves’ free labor provided slave masters the opportunity for financial success. I cannot imagine slave owners wanting to abolish slavery.

Slaves had no legal rights. The federal government did not recognize slaves as human beings, so they had no United States constitutional rights. Yet slavery became a moral issue to Northern Christians, especially Quakers. Some Christians began to speak out loudly and to declare slavery morally wrong.

However, 1863 proved a difficult time for Mississippi. Harry and his wife Martha remained on the Bethesda Plantation with the Wells family. They stayed there throughout the Civil War and afterwards. Slave masters took slaves to join the Confederate Army, and I believe some Turner family members joined the Confederate Army. Upon arrival, the slaves mostly got assigned to front lines; some slaves who survived ended up with the Union Army. Ulysses Grant’s army took soldiers from the Confederate Army when they won particular battles.

The Union Army outmatched the Confederate Army in the Battle of Champion Hill, Hinds County, Edwards, Mississippi, May 16, 1863. Slaves, mostly uniformed, must have been confused. Although the slaves wanted to be free like other Americans were, they knew nothing but plantation life. They could not read or write. We know it was unlawful to teach slaves to read and write, although a few children taught their playmates to read so they could play board games with them. We know some mistresses taught cooks to read so mistresses did not have to remain in the house to read recipes for the cooks. We also know most slaved did not read or write.

The Union Army assumed responsibility for those slaves who tried to escape to the North. Harry and Martha remained where they were. During the spring of 1863 Harry and his master learned the Union Army had moved toward Hinds County, Edwards, Mississippi, en route to Vicksburg, Mississippi. They learned the Union Army was in Yazoo City, Mississippi, nearly fifty miles from the Bethesda Plantation, and I think they knew they had to protect the cotton produced on the plantation.

“During the Civil War at the time when General Grant was approaching Edwards and the Bethesda Plantation in his drive on Vicksburg, the plantation had fifteen bales of unsold cotton on hand.” 9

I believe and the documents suggest that instead of trying to protect his family, Harry chose to protect property. Before the war his job had been to protect the property and to direct other slaves, so why would he do anything different during the war? The documents also suggest that although Thomas had many slaves on his plantation, he chose Harry to help him hide the cotton. According to the records, they took the fifteen bales to an island within a river. The Big Black River was in the general vicinity, but it was about fifteen or more miles from the plantation. However, a creek ran right through the plantation. I think they used the creek. I believe Harry and Thomas chose some inconspicuous spots in the creek, dug holes for the bales and placed them inside. Then they covered the spots with nature’s brush vegetation.

“They were the only two who knew of its existence. The Northern army passed through, but did not find the cotton.” 10

“My great-grandfather, Thomas Wells, the planter, operated a plantation of 1,500 acres with nearly one-hundred slaves at the beginning of the Civil War. Harry was his manager. Both these men were outstanding in their time, and the affection and friendship between them lasted until death.” 11

When I was a child, from 1939-1962, I lived on our family farm. The creek runs through our property, and it came in handy during extremely dry weather. We washed our laundry down at the creek when the water in our cistern became rather low. (Commercial running water in that section of the county came much later.) This is how I know about the creek, and I know how Thomas and Harry might have hidden cotton bales in it.

After General Robert Lee surrendered to General Ulysses Grant in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4, 1863, the Union Army began controlling the Mississippi River. The events thereafter changed. At the end of the war, Thomas Wells’ economic welfare surpassed most former slave owners. Cotton was scarce. The price of cotton skyrocketed, and the Wells family made money because of the hidden commodity.

“After the war the cotton was found in good condition [and was] sold for $1.00 a pound and it was the proceeds of that sale that enabled my grandfather, when he returned from the army, to attend the University of Mississippi.” 12

Harry had been a responsible and good helper for many years, and Wells rewarded him.

“When the war was over, my father gave him 120 acres of land upon which he lived during the rest of his life.” 13

According to Helen Griffith in Dauntless in Mississippi, in the fall of 1865 the Mississippi legislature passed laws which could be considered caste laws. They did not apply to white people. The Black Code denied the rights of Negroes to purchase or rent land. In 1870 the same year the Union re-admitted Mississippi, a race riot occurred in Clinton, Mississippi. Thomas Wells had begun to practice law in Raymond and was there when tensions in the Clinton-Edwards-Raymond area boiled high. Both colored and white individuals lost their lives in the Clinton Riot. As he was leaving the Raymond Courthouse, Attorney Wells was attacked and left to die. He survived but did not see the person who assaulted him.

“My great-grandfather sent for Harry Turner and offered a reward of $1,000.00 for the arrest of the person who had inflicted the injury.” 14

Because he lived in this small community, Harry knew what went on. Harry found out who had beaten Thomas, gave the information to officials and they made an arrest. One thousand dollars meant more in 1870 than it does in 2014. However, Harry refused to accept the $1,000 reward. Harry believed in doing what he thought was the right and Christian thing to do. I smiled when I read that Harry had refused the reward.

“Aunt Martha died—Uncle Harry lived single with his daughter, Hannah, until he died about ninety years of age. Uncle Harry and his wife were devoted to each other and lived an ideal life. He was a man of great physical strength, fine judgment and devoted to his friends and believed the best friend he ever had was my father.” 15

General William Sherman of the Union introduced the promise of “forty acres and a mule” to freed slaves. Some people in Georgia and the Carolinas had begun to enjoy their acquired property. But in 1865, during Reconstruction, President Andrew Johnson ordered the government controlled land be returned to the previous owners.

After Martha’s death, Harry asked the Wells to write a will for him so he could leave his 120 acres to his three daughters. Of course the Wells carried out Harry’s wishes. They also surveyed the land for free and divided it equally among the daughters as Harry had requested.

Harry did not need to worry about the “forty acres and a mule.” Other slaves throughout the state received nothing. However, Hinds County slave owners did receive compensation for losses of freed slaves. A compensation request form with my relatives’ names and values is included in my historical documents.

(Harry, 45, $1,800; Martha, 40, $1,200; Alexander, 15, $1,500; Jefferson, 11, $1,100; Milton, 9, $900; Indiana, 13, $1,200; Charlie, 7, $700; & Lively, 5, $500.)

Records show two children died. I was shocked and dismayed to learn the United States Government compensated the former slave owners but saw fit to give the freemen nothing! Yet this history suggests to me why, despite the fact that other minority groups who were deprived and mistreated in our beloved country have been compensated, some people still disagree with reparation.

“In 1871 my great-grandfather, Thomas Wells, propounded a claim with the United States for reimbursement [for] slaves owned by him which had been freed under the Emancipation Proclamation. In this claim the slaves are listed, giving each name and value. A Xerox copy of this instrument is enclosed.” 16

At Christmas time Harry’s daughter, Indiana, sent Thomas Wells five dollars to purchase something that could be kept in her family forever.

“I bought a silver butter knife and want it to go to my son, Calvin, and then to his son, Calvin.” 16

The Turner daughters later moved up North seeking better opportunities. Sadly, they sold all their property. Harry’s six sons received no land because Harry thought they lived wild lives. The Turners believe all Harry’s sons remained in Mississippi. I am certain my grandfather, Charlie, did. The sons probably would have kept the property.

“I am the granddaughter of Charlie Turner. My mother, Lydia Turner, married Willis Allen . . .” 17

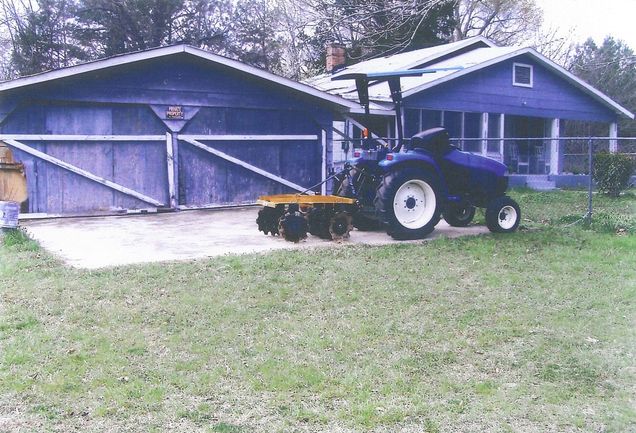

Charlie was Harry’s eighth child. His birthday is listed in family records as April 25, 1857. His death is recorded as January 1935 or 1936. No day is given. Lydia was the daughter of Charlie Turner. Lydia married Willis Allen and they purchased 60 of the original 120 acres from Hilliard Canada, a local white farmer, and built a house in 1930.The house had two bedrooms, a kitchen, a dining room, a living room and a built-in hallway which extended the length of the house. The house, like many other Southern structures, had a porch extending across the entire front. It still stands today.

Family documents indicate that at that time Turner decedents had regained 60 acres of the 120 acres. Lydia and Willis had one daughter. They named her Matlean Allen. Matlean married Fred Douglas Moffett. I am the fourth of six children of Fred and Matlean Moffett.

Unfortunately, Willis died a few years after he and Lydia had bargained for their farm. Therefore, Lydia decided to sign the property over to her only child and son-in-law. In the 1950s, Harry’s youngest daughter, Indiana, gave Fred and Matlean an opportunity to purchase her share of the property, but local banks in Mississippi refused loans to Colored citizens. Fred and Matlean had no money and could not purchase the property. Had Mother and Daddy been able to purchase Indiana’s share, we would own all 120 acres.

In 1980 Fred and Matlean purchased thirty acres of the original 120 acres from Lodge Baity, an African America farmer who had acquired it. That is the story of how the Turner family regained 90 of the 120 original acres. Oh, I wish I could purchase the other thirty acres!

Inheritance means many things to many people, but my family and I believe we own priceless property. There will never be an opportunity for me to inherit additional land that has such a history. I love the place. I adore the property. I value this historical site so much sometimes I shed a few tears when I think about my slave ancestors who lived and worked on and for this place. I get chills when I walk through the bedroom where I was born.

The family feels the 90 acres have a significant historical value for Hinds County. It has been suggested our property is probably the only site in the county with this connection to slavery and the Civil War. We have also been told, not only is it the only property in the county with that historical background, but also it is possibly the only property in the entire state of Mississippi that has documentation to prove it was given to a slave by his former slave master. Therefore, I plan to begin researching the possibility of making the location a historical landmark.

The location of the property follows the history of slavery. Slaves lived in shacks off main roads. I remember seeing portions of old shacks, cisterns where the shacks stood and tomb stones marking graves. The property is seven tenths of a mile off the main road. As a child, I hated that, but now I love the privacy our property provides.

Fred and Matlean’s descendants, who now own the property, bubble with pride and joy over the legacy Harry and Martha left them. Harry and Martha are buried in the Little Zion Missionary Baptist Church Cemetery, Edwards, Mississippi, and I visit the graves often.

“You have every reason to be proud of your ancestors, especially the ones from the Bethesda Plantation.” 18

Although former American slaves did not get the “forty acres and a mule” as they were promised, Harry Turner and Martha Turner enjoyed 120 acres their former slave master and friend deeded to them despite the Black Code.

In 2014 as I write this essay from Hinds County, Mississippi, I am enjoying the fruits of my slave ancestors’ labor. I am proud!

Sources

Griffith, Helen, Dauntless in Mississippi, the Life of Sarah A. Dickey, Dinosaur Press, Hadley, Mass. 1956.

Works Cited

Turner, Alfonzo, Compiled, Lyles, Naomi Moffett, Digging for Roots, Unpublished, September 30, 1978.

Endnotes

1. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, October 28, 1964, p. 20.

2. Ibid., p. 20.

3. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 27, 1962, p. 15.

4. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 2, 1962, p. 9.

5. Ibid. p, 7.

6. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 2, 1962, p. 7.

7. Ibid. p. 7

8. Turner, Alfonzo, Digging for Roots, September 30, 1978, p. 33.

9. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 27, 1962, p. 15.

10. Ibid., p. 15.

11. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 2, 1962, p. 7.

12. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 27, 1962, p. 15.

13. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 2, 1962, p. 8.

14. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 27. 1962, p. 15.

15. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, October 28, 1964, p. 20.

16. W. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 2, 1962, p. 8.

17. Matlean Allen Moffett, Personal Communication, April 29, 1963, p. 18.

18. Calvin Wells, Personal Communication, December 27, 1962, p. 16.

Internet