Flour, Polenta, and Butter

Staples provide us with the basis of variety, and variety itself does seem to be one of our primal needs. COVID-19 has forced us to rethink what our staples are, what they mean to us, and our relationships with them. The following is a creative nonfiction piece, a collaboration by three classmates from Karen Pepper’s Food and Literature class, and is about the ways we are coping and thinking about our staple ingredients.

An Ode to the Staples I’d More or Less Forgotten About and How to Wing it with Them

Lauren Allen

This time has given me space to reflect on the staples. Flour, in particular. No, I am not baking bread,like a large portion of the inspired population, though I do not blame them for stress baking.

I am here to talk about the roux, the building block for other things: sauce, a thickener, maybe gravy. Mac and cheese is made of things that last: flour, butter, pasta, cheese, and salt. A béchamel may sound intimidating, but is nothing more than a handful of ingredients— those listed (sans pasta), and milk. Cook the pasta, drain and set aside. In a pot, over a medium heat, add a few knobs of butter, a healthy amount (here “healthy” means “generous”). Let melt, and add a spoonful of flour (about equal parts butter and flour). Whisk constantly for a couple minutes. Slowly whisk in a couple cups of milk and incorporate into the roux; let thicken, whisking occasionally. When thick, add loads of grated cheese, taste, and season with salt. Add vinegar or Tabasco to brighten it up. Pour the sauce over the pasta.

Alternatively, use a roux to thicken a soup and make it heartier. Melt the butter, whisk in the flour, then whisk vigorously, directly into a soup that is cooking. Let it simmer together for a few minutes. Play around with how long you cook your roux, using a dark roux or a light roux to experiment with depth of flavor.

Some use flour only to make vegan roux, the “dry roux.” Lay out some flour on a sheet tray and toast it in the oven. Whisk it into whatever sauce or soup to add body.

Staples foster versatility in cooking. I’m remembering ways to use flour that I’ve been too lazy or too busy to pull out of my back pocket. Flour is always laying around for one reason or another; now it’s for me and not the moths.

“Mush:” the Staple I Never Knew I Needed

Victoria Collins

Throughout my childhood I would look forward to Grandpa's "mush." My Grandpa was the king of making breakfast—bacon, sausage, homemade sourdough pancakes, fried eggs, toast, a big glass of OJ, and fried “mush”— a breakfast fit for a queen. The aromas drifting from the kitchen would linger throughout the air, hinting to my nose that breakfast was ready. I have gone through my life not knowing exactly what "mush" was, aside from the fact that it was delicious. Crispy on the outside, chewy on the inside, slathered with butter and syrup. Who knew it would take a pandemic to awaken my inner child-like appetite and reintroduce the beloved "mush" back into my life?

The stores were bare and the shelves almost empty as I reached for the polenta loaf. What is this? I added it to my cart and knew that I could create something with this reasonably priced cornmeal product. When I brought it home and slit open the package, I was in shock. It looked and smelled like "mush." I took out my cast iron skillet and melted some butter. I sliced the log into thin pieces and threw them into the skillet over medium-high heat. You want the “mush” to get crispy on the outside, with a dark brown crust. After flipping them once, they were ready. A little butter on top and warm syrup to taste. You want your fork to crack into the crust you've created and then dip the piece of “mush” into buttery and syrupy goodness. Now that I know the true identity of “mush,” I’m adding it to my personal “belt” of staples.

Be Careful with the Butter

Kate Watson

It was the “Don’t come in here, Mom!” that made me leap up from the couch. (Though the absolute silence from the kitchen, after some faint scraping sounds, had raised my suspicions.) I surprised my son when I walked in on him: there he was, standing on a step stool, butter dish askew, the neat rectangle violently smooshed and gouged. The perpetrator clutched a large spoon and his face showed smeared traces of his crime.

Two months ago, I would have regarded this behavior with mild annoyance and amusement, a to laugh for the family group text. My son has always loved eating butter, something many might indulge in if it weren’t for the cripplingly unhealthy consequences of such a habit.

Now this brought a different feeling: a bloom of panic in my chest. This wasn’t any butter— this was the second to last stick of Kerrygold—which had been sold out at the grocery store the last two times we suited up into our PPE to replenish our supply! If we used it all, we’d have to switch to the languishing stick of ersatz vegan butter, left over from a dairy free houseguest. I found myself spiraling into wild theories about the international butter trade— was this the beginning of the end? Would they still manage to milk those Irish cows and fly Kerrygold across the Atlantic?

Like my son, I too love butter. I enjoy it every morning on toast. This minor indulgence, a daily staple in our house, felt threatened. Luckily, my worst fears proved false and we were able to replenish our stock within days. I hope that I can feel cavalier about a stolen tablespoon again.

The reliable and mundane has become precious. We use and think about our staples differently than before, re-discover food memories, and cherish what we have taken for granted.

Molecular Gastronomy at the World’s Best Restaurants

This week we are featuring work from students in Val Ryan's class The Science of Food and Cooking (MET ML619). Today's post comes from Gastronomy student Madiyar Tyurin.

Food science and the way it affects the field of gastronomy is a relatively new movement in the world of fine-dining restaurants. For centuries, people had been practicing standard and universal cooking approaches. Experimenting with food and creating new techniques of cooking started at the end of the twentieth century. Today, those restaurants where that movement began are some of the most well known in their countries and in the world. This essay is going to analyze three restaurants, elBulli, El Celler de Can Roca, and Noma, where chefs and their cuisines are highly influential on their guests, colleagues, and the entire generation of rising cooks. The concept of molecular gastronomy together with their culinary brilliance have affected the formation and professional views of three top chefs in the world and resulted in the breakthrough and rise of their restaurants to the highest positions in the world.

Most of today’s world-known restaurants were inspired by elBulli, a Spanish restaurant of molecular cuisine where Ferran Adrià created experiments with food. He stood out of the traditional chef image and was invited to Documenta in 2007. It is a highly prestigious art event in Europe that is conducted once in five years (Domene-Danes 2013, 100-126). Adrià revolutionized food by introducing such techniques as spherification or foam making from fruit juices. Participation in the Documenta fair meant that his dishes were no longer a product of the restaurant but the manifestation of art. At that time, elBulli turned into an exposition pavilion, and guests of the restaurant were considered as participants of the fair as well. His approach might sometimes be regarded as anti-synesthetic because Adrià tried to combine incompatible things, but the chef proved uniqueness by successfully introducing techno-emotional dishes in reality. Adrià’s meals combined different culinary techniques and often aimed at invoking memories. Opazo argues that achievements at elBulli created a new level of cooking that positively influenced all other chefs in the world by forcing re-thinking and re-evaluating of their ideas and knowledge (2012, 82-89). According to Solier, such desserts as liquid nitrogen pistachios at elBulli are the result of chefs’ creativity and enlightenment (2010, 155-170). It is not about traditional cooking, but scientifically proven decisions that drive Ferran Adrià to create and influence (ibid.). However, Kaufman might criticize this approach by claiming that a guest of the restaurant was no longer an independent actor at the moment of dining, as the chef promoted their own authority by telling how to eat a certain dish (2016).

(The Love of Gardening Project)

One of the most famous restaurants in the high gastronomy industry is located in Girona, Spain and called El Celler de Can Roca. It is run by three brothers, Juan, Josep and Jordi Roca, who work as a chef, a sommelier and a pastry chef there. Girona is a part of the Catalonia region, which is well-known for its terroir nature resulting in distinctive flavors and taste (Meneguel, 2017). A combination of unique climate conditions and geographic location between sea and mountains resulted in a distinctive taste of anchovies, shrimps, bovines, lamb and duck, sausages and mushrooms (Vila, 2016). Meneguel says this region was named as the best gastronomic place in Europe in 2016 and the Roca brothers’ contribution to connecting food with surrounding landscapes and culture is indeed meaningful (2017). They focus on innovation of traditional dishes using local ingredients that carry cultural meanings with the incredibly aesthetic style of serving compared to some artistic events (ibid.). Ulloa et al. argue that the concept of nostalgia or using memories to evoke emotions and create signature dishes plays a significant role in the vision of cuisine at El Celler de Can Roca (2017, 26-38). Moreover, the restaurant members highlight the importance of sharing food and emotions with others as it definitely enhances personal experience and enjoyment, similar to how traveling together might stimulate greater excitement than experiencing the same things alone (ibid.). Some of their signature dishes include the yin-yang oyster that is based on the idea of contrast when a cold oyster is served with a hot sauce, chocolate truffles in a closed rock with a real moss inside as a tribute to forests surrounding the region, or a green salad where all ingredients, such as avocado, lime, melon, cucumber, tarragon, eucalyptus and olive oil are green (Aulet et al. 2016, 135-149). As Barcelona is the capital of Catalonia, they spent their whole childhood watching soccer games and decided to make a “Messi’s Goal” dessert to praise the best soccer player in the world playing in Barcelona.

(So Good Magazine)

Noma is another one of the most prestigious restaurants in the world, located in Copenhagen, Denmark. It is a place characterized by modern Nordic cuisine, and Rene Redzepi represents a new generation of chefs who value old traditions and creative thinking. The word Noma is derived from Nomadic and Mad that means food in Dutch. Goulding claims that the number of tourists coming to the country in search of gastronomy experiences at Noma grows significantly every year (2013). Redzepi tries to reconstruct a classic restaurant model. According to Tressider, Noma’s concept is based on making unique dishes from organic products picked at local lands that embody the history of the culture and its environment (2014, 1-17). Noma could be considered as the modern type of restaurant with its own distinctive characteristics similar to the French wine concept terroir in a way that dishes created there would not be possible to re-create once moved away from the original location (ibid.). As Trubek suggests, the terroir concept attracts millions of tourists to come to a particular place in the world to experience new foods and emotions (2009). Therefore, cuisine is strongly tied to surrounding nature, and meals are changed three times a year representing different seasons. Tressider says as globalization continues to remove borders and boundaries between countries around the world, the growth of terroir restaurants could be considered as an attempt to save local values and natural response to the international homogenization (2014, 1-17). Looking at the past of Dutch history, Redzepi found that citrus plants had not grown in Denmark, and people used to eat ants that have a citrus taste to supplement the flavor of seafood. Therefore, one of the most recognizable dishes at Noma is the live ants in mayo and traditional doughnuts with sardines. Again, as the terroir cuisine is tied to geographic boundaries, it cannot be replicated anywhere else. Therefore, at a master class by Noma in London, serving dishes were largely minimized, as, for example, ants could not be delivered safely to the UK (BBC, 2009). De la Barre and Brouder argue that guests coming to terroir restaurants get unique experience encompassing all senses by terroir (2013, 1-11). It is a mechanism embodying culture, customs and place (Tressider 2014, 1-17). People from all over the world come to Copenhagen with the specific purpose to visit Noma. As Goulding explains, this trend has been called Nomanomics, meaning that the success of one place created a large attraction to the country as a whole (2013). So at this place the bond with nature is important as cuisine manifests more than chemical principles and traditional cooking techniques. Visiting Noma reflects in the adherence to creating personal identity.

(Alexander Saffron)

This essay discussed three high-class restaurants that are elBulli, El Celler de Can Roca, and Noma. All of them are characterized by a unique approach to cooking based on experimenting with food and techniques and bringing their own new vision to the culture of eating. Chefs of these restaurants did not fear expressing themselves and their ideas on the plates. This resulted in the entire movement of the popularization of molecular gastronomy and experimental cooking in the world. Today, all top restaurants try to experiment with the food to a certain extent. One of the issues that might arise with the chefs who reached all awards is the possible lack of interest and motivation to continue expressing their beliefs in the kitchens. Therefore, it is important to develop the entire sphere of molecular gastronomy at restaurants overall as competition might lead to a new level of achievement in this industry.

Bibliography:

Aulet, Silvia, Louis Mundet, and Josep Roca. “Between Tradition and Innovation: The Case of El Celler de Can Roca.” Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism 2 (2016): 135-149

De la Barre, Suzanne, and Patrick Brouder. “Consuming stories: placing food in the Arctic tourism experience”. Journal of Heritage Tourism 8, no. 2-3 (2013): 1-11

Domene-Danes, Maria. “El Bulli: Contemporary Intersections Between Food, Science, Art and Late Capitalism.” Barcelona Research Art Creation 1, no. 1 (2013): 100-126

Goulding, Matt. “Nomanomics: How One Restaurant Is Changing Denmark’s Economy.” TIME. Roads & Kingdoms, February 14, 2013. http://world.time.com/2013/02/14/nomanomics- how-one-restaurant-is-changing-denmarks-economy/

Inside Claridge’s, 2, “Episode 2,” directed by Jane Treays, aired December 11, 2012, on BBC Two, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01pc3gk

Kaufman, Cathy. “Etiquette, Power, and Modernist Cuisine.” Dublin Gastronomy Symposium, 2016.

Lane, Christel. “The Michelin-Starred Restaurant Sector as a Cultural Industry.” An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 13, no. 4 (2010): 493-519

Meneguel, Cinthia. “El Celler de Can Roca and its role in stimulating the creation and development of gastronomy tourism products.” Master’s thesis, University of Girona, 2017.

Opazo, Pilar. “Discourse as driver of innovation in contemporary haute cuisine: The case of elBulli restaurant.” International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 1, (2012): 82-89

Saffron, Alexander. “World’s best restaurant Noma serves live ants.” The Telegraph, March 22, 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/foodanddrinknews/11379809/Worlds- best-restaurant-Noma-serves-live-ants.html

Solier, Isabelle. “Liquid nitrogen pistachios: Molecular gastronomy, elBulli and foodies.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13, no. 2 (2010): 155-170

So Good Magazine. “Messi’s goal.” March 22, 2020. https://www.sogoodmagazine.com/pastry- blog/pastry-chef-articles/jordi-roca-creativity-beyond-a-dish/attachment/gol-de-messi/

The Love of Gardening Project. “Liquid Nitrogen Pistachios: Molecular Gastronomy, elBulli and foodies.” March 22, 2020. https://www.theloveofgardeningproject.com/liquid-nitrogen- pistachios

Tressider, Richard. “Eating ants: understanding the terroir restaurants as a form of destination tourism.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change (2014): 1-17

Trubek, Amy. The Taste of Place. Berkley: University California Press, 2009.

Ulloa, Ana Maria, Josep Roca, and Heloise Velaseca. “From Sensory Capacities to Sensible Skills: Experimenting with El Celler de Can Roca.” Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies 17, no. 2 (2017): 26-38

Vila, Angela. “Girona candidata a Ciutat Creativa UNESCO de la gastronomia?” Master’s thesis, University of Girona, 2016.

Pickles and Transfems: Hormonal and Cultural Food Craving in Gender Transition

This week we are featuring work from students in Val Ryan's class The Science of Food and Cooking (MET ML619). Today's post comes from Michelle Samuels.

Craving pickles is a commonly reported experience among transgender women and other transfeminine people undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The commonly held explanation involves a potential sodium-wasting side effect of one of the HRT drugs, but this relationship has not been formally studied. Further, it remains unclear why pickles have taken primacy as the object of this common craving.

To better understand this relationship between transfeminine people and pickles, I have examined existing research on other hormone shifts and food cravings, hunted down early mentions of the phenomenon, and conducted short, informal interviews with transgender and cisgender peers and with the primary care physician who has overseen my own medical transition.

In the end, I have concluded that some transfeminine people experience food cravings during hormonal transition, some of these cravings are from HRT-related sodium wasting, and this sodium-wasting sometimes leads to craving pickles over other salty foods—but that this alone does not account for the communal narrative about pickles and cravings.

Instead, it appears that the pickle has taken on a complex symbolic importance: as a common experience in a community in need of commonality; as an expectation and touchstone for those undergoing an uncommon, understudied, and underrepresented medical process; and, perhaps above all else, as validation.

1) Pickles and Transfems, an Introduction

In 2017, Jennifer Finney Boylan, a transgender author, received a jar of pickles from a fan at a book signing. “As the night wound down, a transgender woman approached the signing table and handed me an enormous jar full of kosher dills,” Boylan recalled two years later. “’I made you these pickles,’ she said somberly, ‘in solidarity.’”

Boylan was baffled, but quickly caught up:

Apparently the meme began because transgender women in transition often take the drug spironolactone, an anti-androgen that has the side effect of making people crave sodium. Which is where the pickles come in; if it’s salt you’re after, pickles will definitely do the trick. (Boylan 2019)

First, what is spironolactone, and how might it contribute to pickle cravings?

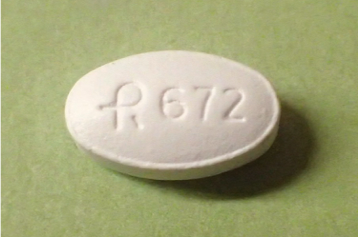

2) “Spiro”

Spironolactone, popularly called “spiro” in the trans community, is a diuretic most commonly used to lower blood pressure via its effect on the water- and salt-regulating hormone aldosterone, causing the body to absorb less sodium and more potassium. (When I began taking spiro, I was told to limit my intake of potassium-rich foods; why has pickle craving taken off as a trans symbol, but not banana avoidance?)

Aldosterone is also one of the androgens, a set of hormones associated with “masculine” characteristics in hair distribution, skin texture, muscle mass, genital formation and function, and other areas. In the 1970s, doctors treating hypertension in cisgender women noted that spiro also reduced their androgen levels, leading to spiro becoming a standard medication for treating the symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Ober and Hennessy 1978). With the discovery that spiro in doses of 100mg daily and above can also directly inhibit testosterone production, the drug became a standard part of transfeminine HRT (Tomlins 2019).

Transgender medicine has long operated outside of the medical mainstream (Safer and Tangpricha 2008), so there is limited research and understanding of the finer points, such as food cravings. However, a patient handbook on PCOS notes that patients taking spiro should be wary of sodium loss, and recommends "eating saltine crackers, a small sour pickle, or any other salty snack before exercise." (Futterweit and Ryan 2006, 181; emphasis added)

Pickles may “do the trick” for the sodium-craving side effect of spironolactone, but so might saltines, potato chips, or salted peanuts. Why, then, has the pickle become so central that a fan would somberly present a jar to Boylan?

3) The Research: Hormonal Shifts and Food Cravings

Could other changes from HRT also contribute to food cravings, perhaps giving pickles an edge with their qualities beyond saltiness, such as sourness?

Again, while transgender food cravings are unstudied, there is some research available for cisgender women.

In a review of 14 studies of taste and preference in pregnant women, Weenan et al. found that many women experienced some change in their sense of taste during pregnancy, including a decrease in the perception of saltiness later in pregnancy, and an increase in liking and consuming salty snacks in the second and third trimesters. The review also identified a higher threshold for bitterness in the first trimester and a preference for sweet snacks in the second trimester, but no significant or consistent change in perception or preference for sourness (Weenan 2018), and so, no answers for the popular trope of pregnant women craving pickles, when, again, saltines would do the trick.

Faas et al. trace hormonal appetite changes to estrogen and progesterone levels during pregnancy and in the ovarian cycle: Appetite decreases when ovulation boosts estrogen, and increases during the high-progesterone luteal phase (i.e., the time between ovulation and the beginning of menstruation) as well as during pregnancy (Faas 2009). Transfeminine HRT almost always includes estrogen, and in some cases, includes progesterone to aid in breast development and counter some cardiovascular, cancer, and bone density risks of estrogen and reduced testosterone (Prior 2018).

So, based on the findings of Faas et al., and perhaps of Weenan et al. as well, the usual transfeminine HRT cocktail containing estrogen much more often than progesterone would reduce appetite and associated cravings. In other words, the apparent parallels in food cravings in HRT and in the ovarian cycle and pregnancy are not so parallel after all. However, these parallels may still have a cultural role in the experience of transfeminine HRT; more on this later.

The diuretic side effects of spiro, then, remain the best physiological explanation for pickle cravings in transfeminine HRT. However, as discussed above, spiro does not explain why pickles have surpassed other salty foods to represent this phenomenon.

4) Let’s Have a Kiki: A Qualitative Survey of Trans and Cis Hormone-Related Food Cravings

I contacted my own primary care physician, Dr. Joseph Baker at Fenway Community Health Center in Boston, who has overseen my entire medical transition, and asked him about cravings for salty foods, or pickles in particular, in patients undergoing transfeminine HRT. “I have observed some anecdotes,” he said. “Unfortunately, I haven't been able to find any reliable sources of information on food cravings with hormone therapy. This may be an area that needs to be investigated further.” He also checked in with colleagues, who similarly noted hearing anecdotes about food cravings and increased overall appetite, but no published research.

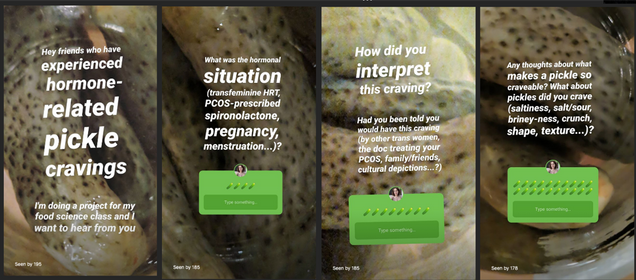

To at least gather more anecdotes, I conducted an informal, qualitative survey of friends and acquaintances to gather reports of cravings associated with any and all hormonal shifts. I used Instagram to conduct this survey, with initial questions on Instagram Stories and follow-up questions in Instagram direct messages, in February and March of 2020.

Respondents included four cisgender women, six nonbinary transmasculine people, and five people across the transfeminine spectrum (two of them identifying as trans women), all in their 20s and 30s; one transgender woman was African American, one cisgender woman was Asian American, and the rest were white. They shared experiences during both transfeminine and transmasculine hormonal transition, pregnancy, and ovarian cycles. Because of varying levels of comfort sharing such personal information, here I identify all respondents by their initials for consistency. See the Supplement after the Works Cited section at the end of this paper for all of the responses.

Consistent with the research on pregnancy described in the previous section, two cisgender women and one nonbinary transmasculine person reported pregnancy-related pickle cravings. “I already loved pickles, it just intensified—also kimchi, sauerkraut, etc.,” said AB, a cisgender mother of two. JC, another cisgender mother of two, reported that she craved pickles because she craved salt, but at the same time pickles were “also kind of fresh? Refreshing?” WR, a transmasculine person who had been pregnant, raised the possibility that their own pickle craving came in part from cultural depictions of pregnancy.

Respondents also reported pickle cravings linked with their ovarian cycles: AE, a cisgender woman, reported craving pickles during ovulation, while CF, a nonbinary transmasculine person, said, “Usually [I crave pickles] as a, ‘Damn, I’m going to get my period I guess.’ Pickle dinner is a near ritual thing when I’m PMSing.” Because AE’s experience is of a craving during an increase in estrogen, while CF’s is during an increase in progesterone, it is difficult to draw any physiological conclusions from these reports.

Surprisingly, several transmasculine people reported an increased desire for pickles after beginning to take testosterone, popularly referred to as “T.” AG said, “My boyfriend and I are both trans masc on T and crave salty vinegar things more than anything now. I didn’t think much of it until he [my boyfriend] brought it up as a hormonal possibility.” Likewise, GJ, who began taking T four or five years ago, said, “I’m not sure, but within that time I definitely noticed I started to crave salty things more, especially pickles.” While transmasculine people may experience some suggestible craving from hearing that other transgender people crave pickles, AG’s experience of a craving beginning before hearing about the trans-pickle connection raises the possibility that some other mechanism may also be at play for individuals taking testosterone, which could also be explored by looking at cisgender men with naturally and medically lowered or raised testosterone levels.

Most interesting for the purposes of this paper, the transfeminine respondents showed no consistency in cravings, with two reporting cravings consistent or semi-consistent with the narrative and three reporting no cravings.

DT, a nonbinary transfeminine person, said, “It was constant for the first six months for me, then kind of died off, and now I don’t crave [pickles].” Those six months began around the time DT started taking estrogen in the form of estradiol, at 2mg/day, when they had already been on spiro at 100mg/day for two months; both dosages were doubled in September, with no reported change in pickle cravings until three months later.

SS, a transgender woman who has been on the same 400mg spiro and 4mg estradiol dose as DT for the last year, reported craving “pickles, capers, and olives.

I think it’s the brine. I’ve always loved pickles, but [now also crave] olives! I have no idea [why], I think it might just be the salty/vinegar taste of the brine, but olives leave this slightly slick mouth feel. Before HRT I couldn’t stand them [olives], but now I can eat a whole jar without hesitation. It feels like I have no self control, I find myself eating things I literally couldn’t stand before, and binging whatever craving comes to mind.

SS’s experience raises interesting questions about the physiological nature of HRT-related cravings; while she reported an increased desire for salt, she also notes a change in liking olives, which she previously disliked because of their oiliness.

On the other hand, the other three transfeminine respondents reported no noticeable change in food preferences or cravings associated with HRT. These three non-cravers included two nonbinary transfems and one trans woman, and were within the same age range as the two transfems who did report cravings.

The five transfeminine respondents reported varying feelings about the pickle craving narrative and experiencing or not experiencing such cravings. “It felt a little validating?” said DT. “I think it was one of those things where it validated my identity as a trans femme person and made me feel like I was being let into a secret club. I knew it was a shared experience among trans femme people and that felt really important to me.”

KG, who reported slowly increasing doses of spiro and estradiol from the same starting dose as DT, echoed this sense of a “club” in describing not experiencing the craving herself:

I heard about this a lot but never experienced it…. I guess I didn’t really mind; I never felt like my gender aligned with what I heard or saw from the broader transfeminine community… and I still don’t, to this day, which is both empowering around my own identity and in some ways feels othering.

Similarly, KT, a transgender woman, did not notice a change from HRT—noting she has always loved pickles, and drank “sips of the juice” even before starting HRT. “I wondered if the whole pickle craving thing was kind of a joke or a social psychological effect,” she said.

The range of experiences reported by the respondents, cis and trans, transfeminine and transmasculine, show the complexity of hormonal changes in human bodies and their relationships with food cravings and preferences. To elucidate these complexities, further research could draw from a larger pool of respondents, with greater cultural, racial/ethnic, and age diversity, and gather prospective data rather than relying on respondents’ recall.

The responses also demonstrate the importance of a social element to the idea of pickle cravings among transgender people, including a sense of validation and being let into or finding oneself outside of a “club,” with even some transmasculine people—perhaps having heard generally about transgender pickle cravings but not the spiro explanation specific to transfeminine people—reporting sharing the experience.

5) Trans Archeology and the Evolution of HRT Cravings

The current state of the transfeminine pickle phenomenon appears somewhat muddled, with many trans people reporting familiarity with it, but only some describing actually experiencing it.

However, the origins and underlying mechanisms of the phenomenon may become clearer by looking to the past. Here, we discover what may be the strongest piece of evidence suggesting the transfeminine pickle phenomenon is not strictly physiological: The pickle only rose to prominence within the last decade.

In her seminal 2007 memoir/manifesto Whipping Girl, Julia Serano describes a strong craving after starting HRT—not for pickles, or any other salty food, but rather for eggs:

I immediately attributed this to the hormones until other trans women told me that they never had similar cravings. So perhaps that was an effect of the hormones only I had. Or maybe I was going through an ‘egg phase’ that just so happened to coincide with the start of my hormone therapy. Hence, the problem: Not only can hormones affect individuals differently, but we sometimes attribute coincidences to them and project our own expectations onto them. (Serano 2007, 66–67)

What Serano describes is the frustration with a common refrain in trans medicine: “Mileage may vary.” Myriad individual factors influence the effects and experiences of HRT, as well as hair removal, surgeries, social transition, and so on. Add to this the lack of accurate popular representation of these processes and the scarcity of “elders” who have gone before; no wonder trans people would grab on to any commonly-reported touchstone, any narrative of what to expect, even one as trivial as craving pickles.

The earliest mention of transfeminine pickle cravings that I could find using English-language Google is from a 2010 message board (much has been written on the astonishing difference the last ten years has made in trans culture and the complexity and brevity of trans “generations,” see, e.g., Lavery 2019).

The original poster asks:

why do I crave salt so much….?

Is it the spiros highish doage that does it? Or do I just like salt…

I feel like I’m never satisfied with it but I always have way too much….

I’ll put sea salt on my had and freaking lick it off…

WWHHHHYYYY? ( “Spiro and Salt Cravings?” 2010; sic)

She is answered by a dozen other trans women, all echoing the same explanation: Spiro is a diuretic.

However, pickles are just one of many foods discussed in the ensuing thread. One responder writes: “Mmmmm, kosher dill pickles, olives, pickled herring, bacon, miso soup, those crazy expensive sweet and salty granola bars… the list goes on and on.” Another reports loving olives stuffed with anchovies. A third respondent is hopefully joking when she writes, “Don't eat rock salt unless it's actual salt, I nibbled a chunk of some chemical labeled ‘de-icer’ and it was vile and not fit for woman nor beast” (ibid).

This message board conversation from 2010 shows that the transfeminine community was already familiar with the sodium-loss side effect of spiro, but that pickles had not yet taken primacy. We have to assume, then, that pickles have taken primacy for cultural, rather than physiological, reasons.

6) Chocolate, and an Answer?

It is a tangent in the 2010 thread about salt cravings that may offer the most insight—a tangent about chocolate.

The tangent begins with one poster writing, “chocolate is amazing. I eat it and I can feel the rush all over my body. Mmmmm, chocolate! Orgasmic! It's not just the taste, but how it makes you feel... I don't know how to explain that. LOL” (“Spiro and Salt Cravings?” 2010; sic).

What is notable about this is not so much that she reports craving chocolate, but the emphatic and decidedly feminine way that she reports a craving especially common among American women. This craving is likely cultural, given that the gender difference in chocolate craving in other countries is much narrower (Hormes 2014).

Here, we see food craving as gender performance, with the poster enacting and emphasizing her female identity through a culturally gendered, commonly-reported food craving (for more on gender performance, see Butler 2011). Considering that women are much more likely than men to report any kind of food craving, at 97% percent of women compared to only 68% percent of men by one estimate (Weingarten and Elston 1990), it seems appropriate that food cravings would hold a special, validating importance for trans women and other transfems. This would seem to explain why, of all of the experiences associated with HRT, a food craving would rise to the top as a symbol, unifying cultural touchstone, and meme.

So, why the pickle? Of the salty food cravings, it is the one most popularly associated in this country with pregnancy (for more on the rise of the “pickles and ice cream” narrative see Onion 2018), making it perhaps the most powerfully feminine of all already-feminine food cravings. The pickle is also meme-friendly, with a long association—via the absurd and the phallic—with drag culture (see, most famously, Rubnitz 1989).

7) Conclusion

As we have seen, pickle cravings in transfeminine HRT have a likely physiological cause in the salt craving effect of the diuretic spironolactone. However, while sodium deficiency from spiro can contribute to craving any number of salty foods, the common narrative about the shared pickle craving experience is fairly new, arising within the last decade.

Rather than a purely physiological phenomenon, this craving has gained prominence in the trans community as a shared touchstone experience, an expectation in a still-mysterious medical process, and as a validation of gender identity through the feminine associations of food craving in general and of pregnancy cravings for pickles in particular. Throw the comic nature of the fermented cucumber into the mix, and the pickle is the perfect candidate for a unique role for a food. Perhaps no other community has, or has quite the same need for, a food role like the craving of the transfeminine community for pickles.

Works Cited

Boylan, Jennifer Finney. 2019. “Why the Pickle Became a Symbol of Transgender Rights.” New York Times, September 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/18/opinion/transgender-rights-pickle-boylan.html.

Butler, Judith. 2011. “Judith Butler: Your Behavior Creates Your Gender | Big Think.” June 6, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo7o2LYATDc

Faas, Marijke M., Barbro N. Melgert, and Paul de Vos. 2009. “A Brief Review on How Pregnancy and Sex Hormones Interfere with Taste and Food Intake.” Chemosensory Perception 3 (2010): 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-009-9061-5

Futterweit, Walter, and George Ryan. 2006. A Patient’s Guide to PCOS: Understanding—and Reversing—Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. New York City: Henry Holt and Company.

Hormes, Julia M., Natalia C.Orloffa, and Alix Timkob. 2014. “Chocolate Craving and Disordered Eating. Beyond the Gender Divide?” Appetite 83 (December): 185-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.018

Lavery, Grace. 2019. “Trans Kids These Days.” April 15, 2019. https://grace.substack.com/p/trans-kids-these-days

Ober, K. Patrick, and John F. Hennessy. 1978. “Spironolactone Therapy for Hirsutism in a Hyperandrogenic Woman.” Annals of Internal Medicine 89, no. 5 (Part 1): 643-644. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-89-5-643

Onion, Rebecca. 2018. “Hysterical Cravings.” Slate, April 18, 2018. https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/04/pickles-and-ice-cream-how-the-crazy-combo-became-iconic-for-pregnant-women.html

Prior, Jerilynn C. 2019. “Progesterone Is Important for Transgender Women’s Therapy—Applying Evidence for the Benefits of Progesterone in Ciswomen.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 104, no. 4 (April): 1181–1186. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-01777

Rubnitz, Tom. 1989. “Pickle Surprise.” Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N733Ofj2cVQ

Safer, Joshua, and Vin Tangpricha. 2008. “Out of the Shadows: It is Time to Mainstream Treatment for Transgender Patients.” Endocrine Practice 14, no. 2 (March): 248-250.

Serano, Julia. 2007. Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, 2nd ed. (2016) New York City: Basic Books.

“Spiro and Salt Cravings?” Susan’s Place, January 24, 2010. https://www.susans.org/forums/index.php?topic=71424.0

Tomlins, Louise. 2019. “Prescribing for Transgender Patients.” Australian Prescriber 42, no. 1 (February): 10–13. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2019.003

Weenan, Hugo, Annemarie Olsen, Evangelia Nanou, Esmée Moreau, Smita Nambiar, Carel Vereijken, and Leilani Muhardi. 2018. “Changes in Taste Threshold, Perceived Intensity, Liking, and Preference in Pregnant Women: A Literature Review.” Chemosensory Perception 12 (2019): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-018-9246-x

Weingarten, Harvey P., and Dawn Elston. 1990. “The Phenomenology of Food Cravings.” Appetite 15, no. 3 (December): 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(90)90023-2

Supplement 1: Results of a Qualitative Survey of Trans and Cis Hormone-Related Food Cravings

AB, cisgender woman: “Pregnancy! I already loved pickles, it just intensified. Also kimchi, sauerkraut, etc.”

AE, cisgender woman: “Ovulation! Need salt/sour to make good eggs.”

AG, nonbinary transmasculine: said, “My boyfriend and I are both trans masc on T and crave salty vinegar things more than anything now. I didn’t think much of it until he brought it up as a hormonal possibility. Being Jewish is an extra layer to this because if it’s not a crisp dill I’m not into it lololol.”

CF, nonbinary transmasculine: “Usually [I crave pickles] as a ‘Damn, I’m going to get my period I guess.’ Pickle dinner is a near ritual thing when I’m PMSing.”

DT nonbinary transfeminine: “It was constant for the first six months for me, then kind of died off, and now I don’t crave [pickles]. It started about a month or so in. I started spiro in May of 2019, and was on 100mg/day. Estradiol started in July 2019, 2mg/day. They both got doubled in September. I’d say cravings started over the summer, sometime just before starting estradiol, and then continued through the end of the year. I 100% had heard of it [the pickle craving]. [Experiencing] it felt a little validating? I think it was one of those things where it validated my identity as a trans femme person and made me feel like I was being let into a secret club. I knew it was a shared experience among trans femme people and that felt really important to me. I haven’t felt that craving in a while, though I do still keep a jar of pickles in my fridge just in case…”

EL, nonbinary transmasculine: “I’m transmasc so I know I’m not the target, but I’m also an RN and we talked about the cravings when I was in school. We were literally told to provide clients with salty snacks, specifically pickles. I went to school at University of South Carolina, they have a campus in Greenville that I attended. We’d discussed spiro in my pharmacology class but it was in a general medical/surgical class that we went over real life side effects. The professor wanted us making care plans for patients on spiro, and the two patient scenarios we were given were for transfem HRT and congestive heart failure. I remember it really well because that was the first time we ever discussed any kind of queer health other than in psych class.”

GJ, nonbinary transmasculine: “Briney crunch [is the appeal]. I don’t know if it’s HRT or what but I crave salty pickled things all the time the past few years. Well, I started hormones four or five years ago, so I’m not sure. But within that time I definitely noticed I started to crave salty things more, especially pickles. Official start date [i.e. age at beginning of HRT] is complicated but let’s just say 26.”

JC, cisgender woman: “Pregnancy made me want something salty all the time. And pickles were salty but also kind of fresh? Refreshing?”

KG, transfeminine: “You know, I heard about this a lot but never experienced it. I’ve always loved pickles, so there’s that, but I never experienced any cravings. I guess I didn’t really mind; I never felt like my gender aligned with what I heard or saw from the broader transfeminine community—which at the time was primarily via Reddit—and I still don’t, to this day, which is both empowering around my own identity and in some ways feels othering. I started HRT when I was 25 and a half (actually on my half birthday!). I started quite low, 100mg spironolactone and 2mg of estradiol (orally) and slowly increased the dosages over a few months. It eventually settled at 6mg estradiol. My spiro dosage had increased to 200mg but I had many issues with dizziness and blacking out, but after two years, I wasn’t feeling enough had changed so my doctor (after a lot of “consulting with colleagues”) increased my HRT dosage to 8mg sublingually, which is what it still is today.

KR, cisgender woman: “I have PCOS but haven’t been on [spiro]. But even when I’ve taken things to ramp up estrogen and stifle T (birth control and/or supplements), I haven’t really had cravings I don’t think. I’ve had PCOS since I was 11, diagnosed at 22 and haven’t taken birth control since then. I take inositol, it works.”

KT, transgender woman: “I’ve always loved pickles enough to drink sips of the juice. I honestly probably did that before starting HRT. I’m on 6mg estradiol a day, and 100mg spironolactone a day which started (at much smaller dosages) in July of 2017, when I was 24 years old. I’ve also been on progesterone (100mg) for about a year now, kinda on and off as I figure out if it’s right for me. I feel and have felt fine about it [not experiencing cravings]. I’ve never put too much thought into it. I wondered if the whole pickle craving thing was kind of a joke or a social psychological effect. Everybody’s body is different, though! Happy for everyone who gets those pickle cravings. Pickles are amazing, and more trans folk eating pickles warms this Jewish trans femme’s heart! I think I might go buy a jar of pickles now.”

LS, nonbinary transfeminine: “I don’t think that I ever experienced this phenomenon, at least not in a way that I noticed. I maybe first heard about it when I read Whipping Girl in the months leading up to starting HRT. I can’t remember if Serano actually mentions the salt/pickle craving, but she discusses the effects of HRT and that was my primer for expectations. [I felt] indifferent I guess [about not experiencing any cravings]. I’ve always liked pickles and always had a preference for salty/savory over sweet. My starting dose when I was 25 was maybe 2mg of estradiol a day and went up to 6mg. I did that with 200mg spiro for a few years, and introduced progesterone about a year into HRT. I’m now on 0.5ml estradiol injected every other week and 200mg of progesterone a day, and no anti-androgrens.”

SS, transgender woman: “Pickles, capers, and olives. I think it’s the brine. I’ve always loved pickles, but [now also crave] olives! I have no idea [why], I think it might just be the salty/vinegar taste of the brine, but olives leave this slightly slick mouth feel. Before HRT I couldn’t stand them [olives], but now I can eat a whole jar without hesitation. It feels like I have no self control, I find myself eating thing I literally couldn’t stand before, and binging whatever craving comes to mind. I’m on 200mg spiro, 4mg estro, and I started when I was 23, which was a year and a few months ago.”

WR, nonbinary transmasculine: “Pregnancy. Cultural depictions, probably. Also nostalgia/comfort? I ate pickles a lot as a kid. Crunch plus brine plus salt plus tang [was the appeal].”

The Murky Marketing of Superfoods—The Case of Açaí

This week we are featuring work from students in Val Ryan's class The Science of Food and Cooking (MET ML619). Today's post comes from Gastronomy student Mara Sassoon.

Açaí: by now, the purple Brazilian berry is ubiquitous in the United States. Most often, it is found in the form of a frozen pulp that is mixed with bananas or other berries into vibrant frozen smoothie bowls, a dish that has become increasingly popular over the past few years, popping up in restaurants and cafés and on Instagram feeds (fig. 1). Recently, even Trader Joe’s and Dole have gotten in on the trend, offering premade versions one can find in the frozen food aisle of the grocery store. But why has the purple treat become so popular?

Jamie Lauren Keiles gets to the main reason for the açaí craze in her 2017 article for the New York Times Magazine titled, “The Superfood Goldrush.” She interviewed the owner of a so-called “superfood café” in Los Angeles about the smoothie bowl’s appeal. His response? “The blend is like an ice cream. But healthy” (Keiles 2017, 34). Açaí, as Keiles’ article points out, has long been hyped as a health-packed ‘superfood,’ espoused for a multitude of potential benefits— marketers like to point out that is rife with antioxidants, and some even point to anti-aging and weight loss benefits from the berry.

Food and nutrition science have become entangled in the problematic strategies marketers use to claim positive health effects of so-called ‘superfoods.’ Examining how açaí or any of the many other ‘superfoods’ out there—among them, blueberries, pomegranate, kale, and quinoa—have been advertised over the last fifteen to twenty years reveals how food and nutrition science are negatively utilized by marketers to influence how people perceive nutrition and healthy eating.

“Every food producer wants to expand sales. Health claims sell. The FDA requires research to support health claims and greatly prefers studies that involve human subjects rather than animals,” Marion Nestle writes in a 2018 article for The Atlantic, “Superfoods are a Marketing Ploy” (Nestle 2018). In the article, Nestle details how food producers fund research to support health claims they make about their food, a perfect example of how food and nutrition science is shoehorned into supporting marketing goals. She specifically points out two producers, Royal Hawaiian Macadamia Nut and Wild Blueberries of North America. The claims their research produced? One: eating macadamia nuts every day could reduce the risk of heart disease and two: Wild Bluberries’ particular frozen blueberries are healthier than fresh blueberries.

As Nestle argues, the research funded by these industries is often misleading, organized around profit rather than around real concern for people’s healthy eating habits. This kind of research and these kinds of claims cast individual foods as cure-alls no matter what comprises the rest of a person’s diet. “To ask whether one single food has special health benefits defies common sense. We do not eat just one food,” Nestle writes. “But when marketing imperatives are at work, sellers want research to claim that their products are ‘superfoods,’ a nutritionally meaningless term.” Nestle would likely agree that the next time one digs a spoon into a frosty açaí bowl, one should think about the studies behind its health claims and who has funded them.

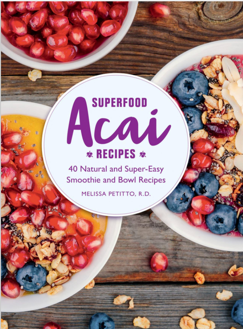

Indeed, açaí is not immune to such sensationalized health assertions. The use of the term ‘superfood’ is rampant when it comes to the fruit. Sambazon, one of the most popular companies for açaí products, labels it as “The Amazon Superfood” on its website (Sambazon, n.d.). The term is also present in relatively new recipe books: Melissa Petitto, a registered dietician, published the 2019 book Superfood Acai Recipes: 40 Natural and Super-Easy Smoothie and Bowl Recipes (fig. 2). At the beginning of the book, she cites the same supposed health benefits of the fruit that are widely promoted elsewhere—among them, positive effects on brain function, high levels of antioxidants and nutrients, and anticancer properties (Petitto 2019, 6). Many restaurants use the catchphrase, too: similar to the café Keiles describes in her article, Vitality Bowls, a popular franchised eatery with locations around the United States, specializes in açaí bowls and also dubs itself a “superfood café.”

In their paper, “Unlocking the Energy of the Amazon? The Need for a Food Fraud Policy Approach to the Regulation of Anti-Ageing Health Claims on Superfood Labelling,” Janine Curll, Christine Parker, Casimir MacGregor, and Alan Petersen delve into the problematic marketing of açaí as a ‘superfood.’ They include statistics to illustrate the sales impact of labeling something a ‘superfood,’ including that “blueberry sales reportedly doubled between 2005 and 2007” because of it (Curll et al. 2016, 420). However, Curll et al. argue that calling something a ‘superfood’ is tantamount to “food fraud,” referring to the misleading labeling or packaging of food. The authors, who are all from Australia, specifically examined açaí products available there, including powders, frozen pulp, pills, and drinks.

One common thread they observed was that many of the products included an “exotic back story” as part of a marketing tactic to make the products’ health claims seem more believable. They write, “Labelling implies that it is the mystical origins in the Amazon jungle itself that contributes to the superior properties of the açaí berry” (2016, 435). While not one of the brands they observed, Sambazon uses the same kind of tactic in its marketing, even working a positive environmental bent into its narrative: “Ancient legend tells us the entire Amazon was born of a single seed of Açaí. A gift from Princess Iaçã (her name spells Açaí backwards), its legendary powers are said to have saved its people from starvation while creating abundance for all who lived there. Today Açaí continues to protect the people of the Amazon, by making the forest more valuable standing than cut down” (Sambazon, n.d.).

Reflecting on Sambazon’s mythical story, however, one must question the impact the ‘superfood’ marketing and subsequent rise in sales of açaí have had on the environment. Extensive detrimental ecological impact due to increased açaí production has not been widely reported, however in a 2015 paper titled “Floristic impoverishment of Amazonian floodplain forests managed for açaí fruit production,” Madson Antonio Benjamin Freitas et al. report on a study they conducted on the impact of heightened demand for the fruit on the forests where it is grown. “Our study is the first to demonstrate a significant loss of local tree species richness and a trend toward floral impoverishment in Amazonian floodplain forests under intense açaí production,” they write, noting a negative impact on the variety of surrounding plant and tree species that they believe should be curtailed through conservation initiatives (Freitas et al. 2015, 24).

Curll et al. also observed that almost all of the products they examined touted anti-aging properties due to the levels of antioxidants found in the fruit (2016, 433). In fact, the rich antioxidant level of açaí is one of its most prevalently advertised benefits. Curll et al. point to açaí’s popularity as starting with a 2005 book by dermatologist Dr. Nicholas Perricone—and a subsequent publicity appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show—in which he discussed the anti-aging benefits of the berry. In said book, The Perricone Promise: Look Younger, Live Longer in Three Easy Steps, he discusses the high level of antioxidants in the fruit and also praises its anthocyanins, pigments containing antioxidants, calling açaí berries “the richest anthocyanin sources by far” (Perricone 2005, 50).

Perricone and others have placed açaí on a pedestal that Curll et al. find problematic. They argue that, while the berries certainly possess many healthful qualities, they are perhaps no more healthy than other foods, writing, “‘superfood’ claims...seek to distinguish some fruit and vegetables, such as açai, from other ‘normal’, unbranded fruit and vegetables on the basis that a particular set of bioactive molecules (or ‘phytochemicals’) in the food are especially potent antioxidants” (2016, 433). Yet, other fruits contain comparable levels of phytochemicals to açaí. Bioactives in Fruit: Health Benefits and Functional Foods, edited by Margot Skinner and Denise Hunter, a more than 500-page tome detailing the nutrient compositions of various fruits, actually groups açaí with grapes, blackcurrants, strawberries, peaches, apples, blueberries, pomegranates, and others in its discussions of fruits with high levels of phytochemicals (Skinner and Hunter 2013, 468). This is yet another example of the potential for food and nutrition science to be used deceptively for marketing initiatives.

Other studies have found that açaí’s antioxidants have not been proven to be fully absorbed by the body. In The A-Z Guide to Food as Medicine, Diane Kraft and Ara DerMarderosian write that recent studies of the açaí berry—the first entry in the book—which is also often consumed as juice, found “‘no consistent clinical evidence of antioxidant potency’ of acai compared to other beverages, such as red wine” and that drinking the fruit’s juice and pulp “raised plasma antioxidant capacity but did not affect other markers of antioxidant activity such as antioxidant capacity of urine” (Kraft and DerMarderosian 2016, 1). These studies noted by Kraft and DerMarderosian show that food and nutrition science can also be used to fact-check health claims made by food companies, ironically, based on food science itself.

Look outside the realm of açaí products, and one can see that the term ‘superfood’ is widespread in food marketing (fig. 3). As Nestle points out in her article for The Atlantic, it is necessary to be an engaged and aware consumer who attempts to discern who conducted the studies that back up health claims and whether there could be any biases present. I realize that food scientists, researchers, nutritionists, and food companies must often work hand in hand due to the FDA’s requirement of research to back up health claims. Still, perhaps there could be more regulatory processes to avoid instances of studies seemingly designed to back up such claims specifically.

As many of the aforementioned scholars have pointed out, ‘superfood’ is a problematic term and, though unrealistic, it would be helpful to stop using the term entirely. It is still used irresponsibly by influential sources. For instance, Harvard is sending out mixed messaging on the term. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health published an article titled “Superfoods or Superhype?” which supports the notion that the term is problematic (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, n.d.). Yet, Harvard Health Publishing ran a blog post in 2018 titled “10 superfoods to boost a healthy diet” (McManus 2018). Doctor Mehmet Oz, regarded as a prominent authority on health topics, uses the term in his book, Food Can Fix It: The Superfood Switch to Fight Fat, Defy Aging, and Eat Your Way Healthy. Although he discusses in the introduction how people use the term problematically and that “no such food exists” (Oz 2017, 2), he is nonetheless using it in the title of his book because it is a catchy and enticing phrase. The term connotes a cure-all food, and as the example of açaí shows, that is an impossible feat.

Works Cited

Curll, Janine, Christine Parker, Casimir MacGregor, and Alan Petersen. 2016. “Unlocking the Energy of the Amazon? The Need for a Food Fraud Policy Approach to the Regulation of Anti-Ageing Health Claims on Superfood Labelling.” Federal Law Review 44, no. 3 (September): 419-449.

Freitas, Madson Antonio Benjamin, Ima Célia Guimarães Vieira, Ana Luisa Kerti Mangabeira Albernaz, José Leonardo Lima Magalhães, and Alexander Charles Lees. 2015. “Floristic impoverishment of Amazonian floodplain forests managed for açaí fruit production.” Forest Ecology and Management 351, no. 1 (September): 20-27.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. n.d. “Superfoods or Superhype?” Accessed March 22, 2020. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/superfoods/.

Keiles, Jamie Lauren. 2017. “The Superfood Goldrush.” New York Times, May 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/02/magazine/the-superfood-gold- rush.html.

Kraft, Diane and Ara DerMarderosian. 2016. The A-Z Guide to Food as Medicine. New York: Taylor & Francis.

McManus, Katherine D. 2018. “10 superfoods to boost a healthy diet.” Accessed March 22, 2020. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/10-superfoods-to-boost-a-healthy-diet- 2018082914463.

Nestle, Marion. 2018. “Superfoods are a Marketing Ploy.” The Atlantic, October 23, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/10/superfoods-marketing- ploy/573583/.

Oz, Mehmet. 2017. Food Can Fix It: The Superfood Switch to Fight Fat, Defy Aging, and Eat Your Way Healthy. New York: Scribner.

Perricone, Nicholas. 2005. The Perricone Promise: Look Younger, Live Longer in Three Easy Steps. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Petitto, Melissa. 2019. Superfood Acai Recipes: 40 Natural and Super-Easy Smoothie and Bowl Recipes. New York: Crestline.

Sambazon. n.d. “Discover the Benefits of Açaí.” Accessed March 22, 2020. https://www.sambazon.com/discover-acai.

Skinner, Margot and Denise Hunter, eds. 2013 Bioactives in Fruit: Health Benefits and Functional Foods. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Images:

Fig. 1. Açaí smoothie bowl by Shari’s Berries. Available from: Flickr Commons, https://www.flickr.com/photos/sharisberries/33343287432/in/photolist-2ahDtTk-LwFo8K- NahEqS-N8pgB2-2ggEzkR-SNr4G5-MDgGLq-wHYMw-7Wb68R-2ggESpV-2ggEouW/ (accessed March 22, 2020).

Fig. 2. Cover of Superfood Acai Recipes: 40 Natural and Super-Easy Smoothie and Bowl Recipes by Melissa Petitto. Available from: Google Books, www.books.google.com/books/about/Superfood_Acai_Recipes.html?id=Pu2ODwAAQBAJ (accessed March 22, 2020).

Fig. 3. Advertising campaign for Health Warrior bars by Elevation Advertising. Available from: Elevation Advertising, http://www.elevationadvertising.com/brand-platform-superfood/ (accessed March 22, 2020

Announcing the 2019 Julia Child Student Writing Awards

Congratulations to Gastronomy students Ilana Hardesty and Sarah Hartwig, winners of the 2019 Julia Child Student Writing Awards.

Ilana Hardesty was recognized for her paper written for Dr. Karen Metheny’s Cookbooks and History class, ‘Tracing Communities Through Recipes’, in which she analyzed Armenian community cookbooks to understand the complexities of diaspora communities in the US.

Sarah Hartwig was recognized for her essay submitted in Dr. Megan Elias’ Readings in Food History class, ‘Out of the Closet and Into the Kitchen: History, Food and Queer Identity’ which addresses the paucity of research on food in the Queer community.

In lieu of a springtime awards ceremony, please join us in virtual toast to the awardees while you enjoy Gastronomy Program director Megan Elias’s interview with Ilana and Sarah:

The Julia Child Student Writing Awards recognize academic excellence in the Gastronomy Program. Each year instructors are asked to nominate several students on the basis of the best final paper or project they have received. Winners receive a certificate and a cash award, made possible by the support of the Julia Child Foundation.

Portions Within the Restaurant Industry

Students in Steve Finn's spring special topics course on Food Waste (MET ML702 E1) are contributing this month's blog posts. Today's post is from Victoria Collins.

Many individuals are aware of the food waste issue in some capacity. Whether you tend to purchase a bit more groceries than you need each week, take more than you need at a buffet, or you’re one of those people who tend to make way more food than necessary during a family gathering in fear that there won’t be enough; many of us can relate to food waste guilt. One issue that particularly interests me is food waste within the restaurant industry. It may come as a surprise that those in the professional food industry still contribute to the food waste issue. Looking back at my camera roll, I noticed a huge difference in portion size depending on which restaurants I took photos at. I was particularly intrigued by a side by side pasta photo collage, pictured below. The photo on the left was taken at Michael Chiarello’s Napa Valley restaurant, Bottega. The photo on the right was taken at Gibbet Hill Grill, in Groton, MA.

Both of these were delicious pasta dishes at a comparable price, made with quality ingredients. The major difference, as you can see for yourself, was the portion size. The pasta dish at Bottega probably aligns with the actual recommended serving size of pasta. It featured such a rich and decadent veal Bolognese sauce, that the small portion was fitting for the sauce and ended up being very filling. On the opposite spectrum, the pasta dish at Gibbet Hill Grill was very large and almost impossible to finish in one sitting. It was a delicious beef stroganoff pasta dish with meaty mushrooms and earthy chives throughout. The sinful yet delicious sauce was so filling on its own, that the massive amount of pasta paired with it, made it truly too large of a dish to eat. I took half of it home because who doesn’t like delicious leftovers the next day? Unfortunately, I noticed that many people in the restaurant were allowing for the waiting staff to clear their plates with a lot of uneaten food left on their plates.

According to The State of Food and Agriculture: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction, written in 2019, “Food waste is the result of purchasing decisions by consumers, or decisions by retailers and food service providers that affect consumer behavior” (4). If food waste can be improved upon through both the consumer and the food service provider, we can attack the issue from various angles. One way that both the consumer and food service provider can help to reduce food waste is through portion control. Restaurants can provide portion options to their customers. This would benefit the consumer through a decrease in price and through food waste control. Offering customers either a half portion or full portion is a great solution to cutting back on excess food waste. If an individual enters a restaurant and wants a lot of pasta or a full sized salad, they have the option to order that specific size. On the flip side, if someone isn’t as hungry and wants something a bit smaller, they can reduce their spending cost as well as food waste. Some restaurants are already offering various portions but if we extend this across the board, I believe we can significantly reduce food waste within the restaurant industry.

Another idea for restaurants is to promote doggy bags and taking excess food home. If restaurants automatically assume that their customers would like to box up their extra food, they are doing their part in helping to reduce food waste. I have been to many restaurants where they automatically take your plate when they assume you are finished with your food. They skip over the step of asking you if you would like to take the rest home. If more restaurants promote this type of behavior, customers will start to assume that anything they don’t finish will be boxed up for them to take home. Even something as simple as the extra bread at the table can be boxed up and taken home for the next morning’s breakfast toast or a late night vehicle for a grilled cheese. These simple recommendations can help to improve our fight against food waste and also create a more mindful atmosphere surrounding food in restaurants.

Control, Alt Delete: Musings about Hoarding and Food Waste

Students in Steve Finn's spring special topics course on Food Waste (MET ML702 E1) are contributing this month's blog posts. Today's post is from Molly Breiling.

How I operate as a culinary professional, does not necessarily mirror my day to day, household practices. When I have job for an individual, or group, I must design a menu based upon what the client desires, married with what makes sense for the particular season and setting. Cost and price are significant factors and staying with the plan is essential. I try to source ingredients on a wholesale basis, and begin preparations well prior to the event. When I am tasked with feeding the inhabitants of our home, I market daily and for the most part devise menus and food planning around what looks good to me. I place an emphasis on fresh vegetables and fruits, and moderate portions of proteins. I do keep a fairly well stocked pantry, even if stored in less than traditional spaces; the coat closet shelf is an overflow space. Impulses, at times, get the best of me, causing me to have more than ample supply of one item or another. Through creativity, this is rarely a difficulty, and does not often create waste. If it cannot be consumed by this crew, the item will be given to a friend or acquaintance who will benefit from the infusion.

Fairly early into the appearance of Covid 19 in Massachusetts, I was at the market for a sortie. What I encountered was nothing less than astounding. I can safely say that I have never, ever, witnessed the behaviors to which I was exposed. Patrons had carts that were full to the brim, with items. Some patrons commanded two carts. Bare shelves abounded. No poultry products, virtually no dairy products, no paper products, cleaning supplies, first aid items, soups, or much in the way of fresh proteins existed.

I was raised during the cold war. I have experienced the gas crisis in the early seventies which resulted in rationing and long lines. I recall when sugar was difficult to source, and when meat was both in short supply and highly priced. I was the parent of an infant living “inside the Beltway” on September 11, 2000, when there was a run on batteries, sterno, dry goods and the like. This experience couldn’t compare to any of those. All at once it gave me pause, and reminded me of food shortage issues in Russia in the eighties, as well as stories told to me by relatives who lived during the depression, or World War I or World War II. The difference is that, currently, we do have choice in the matter!

Adding insult to injury, I would bet the farm, if I had one, that a large percentage of the foods purchased, strike that hoarded, will end up wasted. Further, that they will likely land in the garbage. Panicked, impulse purchases, without any type of plan in place will not only lead to items expiring, or timing out in the case of some packaged goods, it will lead to foods in the freezer that may never be utilized. Emotional purchasing is not planned, well thought out, purchasing. Atop the gross quantity of waste in terms of time, resources and actual food, there is another uncomfortable reality. Food that is hoarded is now inaccessible to other persons, some of whom are food insecure, and/or marginalized in some manner. These behaviors are harming the overall environment and exhibit irresponsible use of resources. Further, such actions potentially place a neighbor in need at even further risk.

Food Recovery in Granero Central: Gleaning in Santa Marta Colombia

Students in Steve Finn's spring special topics course on Food Waste (MET ML702 E1) are contributing this month's blog posts. Today's post is from James Lysons.

The hungry men were seen, followed by their valets, roaming the quais and guards' quarters; gleaning from their outside friends all the dinners they could find; for, according to Aramis, in prosperity one should sow meals right and left, in order to harvest some in adversity.

~ Alexandre Dumas

On vacation in Santa Marta, Colombia, a coastal city east of Cartagena of around a half million people, I took an afternoon, accompanied by a guide, to visit an example of locals gleaning in the Granero Central, the public market of the city. Sebastian (my guide) was proud of his city and assured me that the locals waste little food at the market.

Knowing that I was a Caucasian tourist (a “gringo”) there for the single purpose of observing locals and taking pictures, Sebastian suggested just driving by to observe, within the security of tinted automobile windows.

The market was bustling, with vendors selling fish, produce, textiles, and general goods on tables that lined the streets. Driving in what seemed like circles, Sebastian slowly positioned our car to enable observation of the spectacle he was so proud of. To the left side of the car were large dumpsters, each with several men rummaging through what appeared to be trash bags and food scraps. On the outside of the dumpsters were people instructing what the men should look for. We passed them twice and, on the last lap, I saw a cardboard box newly positioned on a cart containing salvaged celery. It appeared perfectly fine and edible.

Sebastian explained that these rummagers (technically, gleaners) salvage the reusable goods and sell them in the stalls a few meters from the dumpsters at a fraction of the cost of the same items found in the market next door. Their customers are a “lower-class” group of people. Although neither governed nor regulated the system of salvaging works -- it is simple. It provides an ample supply of food for this group of people struggling with limited income and resources. When contrasted with the gleaning that is popularized in Vancouver, Canada, this system is relatively profitable and has created a community. I felt it was the sense of community that largely made the process function and so my inclination was to accept it.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as outlined by the UN, are missing a kind of mortar that might bind all the SDG initiatives as one: a mortar which earlier incarnations of UN development work took more into account when dealing with what it termed “the informal sector.” There are lessons we can learn from the rummagers and vendors in Santa Marta. The community appeared to be the mortar at the Granero General, offering an additional dimension to the issue of food waste while also creating an informal sector community alongside the “official” food market. How can such a “community” become a priority, on a global scale, while outside of the “normal” corporate and government channels, regulations, and controls? After all, in much of the “developing world” significant percentages of the population work, live, and exist throughout their lives in the so-called informal sector. How can we not only accept but find ways to support such a sector while important corporate and government entities deny (or at least fail to act on) the matter of climate change; while powerful religious organizations promote an anti-vaccination agenda; and other industries insist, still, on their right to reduce fish to the brink of extinction?

The perfect answer or solution remains to be seen. Still, these challenges inspire creativity to foster a sense of community that may oppose such denial and/or “anti-this and that.”

We watch the world come together, slowly, amid the zombie-like apocalypse called COVID-19. Must we wait for a food shortage for the world to come together to solve the food-waste problem? The signs are everywhere, and the writing is on the wall.

My experience in Santa Marta, although short, was inspiring.

The Fine Line Between Generosity and Waste

Students in Steve Finn's spring special topics course on Food Waste (MET ML702 E1) are contributing this month's blog posts. Today's post is from Anne Howard.

Doesn’t this look like a feast? At this Chicago Korean barbecue restaurant, grilling your own food is only part of the draw. (That’s marinated octopus cooking on the tabletop grill in the center.) It’s when the server brings out the banchan, small side dishes, that the fun begins—and keeps going and going. The dishes just keep coming: kimchi, of course; salads of cucumbers, broccoli, and potato; and preparations of vegetables like lotus root, bean sprouts, radish, and eggplant. Diners don’t order banchan; they are chosen and provided by the restaurant. Our party of five, including two children (whose faces are covered in the photo), received thirty-one small dishes of banchan.

This was impressive, and certainly made it feel like a celebratory meal. But seeing more dishes than could fit in a single layer on the table also triggered my food waste radar. It caused me to consider how subjective the idea of waste can be. What looks like wasteful behavior to some might look like generosity to others. I wanted to think through my own subjective, culturally-based view of what constitutes food waste and reflect on how my thinking and actions contribute to the problem.

According to Food Cultures of the World, “the Korean table is communal; all side dishes are shared. Koreans are very social eaters and love eating with family, friends or coworkers.” (Albala 2011, 141) Though meals at my home are also served family-style, the dishes are fewer, which made this spread feel excessive. Experiences at other restaurants conditioned me to expect eight to twelve different banchan (even fewer are common at in-home meals (Cwiertka 2003)), so I was surprised by the number of dishes the first time I dined at this particular restaurant.

Cecelia Hae-Jin Lee, quoted in HuffPost, notes that when it comes to banchan at home, “whatever isn’t used is saved for the next meal—so it’s not a waste.” (Bratskeir 2017) This would not meet health codes in a restaurant, however, and as banchan can be difficult to take home as leftovers, more is discarded. As Jonathan Bloom, author of American Wasteland: How America Throws Away Nearly Half of Its Food (and What We Can Do About It), points out, American restaurants serve ever-increasing portions, and that “chefs want what they serve to appear generous.” (Bloom 2010, 133) Americans seem to believe that quantity equals value. The more on offer, however, the more opportunity for waste. In this case, even though the serving of each banchan was small, they added up to a large volume.

However, restaurant owners are always looking for ways to trim costs. Decreasing plate waste saves money on ingredients, labor, utilities and disposal. Even in a cultural setting where multiple small dishes are an important part of the meal, restaurant owners can look for ways to cut back on waste. Our table was served multiple dishes of the same item, for instance, which is unnecessary if the restaurant has a policy of allowing free refills on banchan, as many do. Noting this policy on the menu informs first-time patrons and might also encourage returning customers to ask the server not to bring any banchan the customer doesn’t want to eat, knowing they can have more of the ones they like.

So, is this a picture of waste or of hospitality? It is fair to say we over-ordered because, as first-time patrons, we weren’t prepared for the serving sizes or number of side dishes. It is also possible to argue that, while generous, the restaurant is providing too much banchan for a party of five. We took home most of the banchan remaining at the end of the meal, as well as the grilled meat and the cauldron of seafood stew at the bottom of the photo, which made four more meals. I think this picture shows opportunity—to be more cognizant, as eaters or restaurateurs, of what we can be doing to save food from going to waste.

References