Pickles and Transfems: Hormonal and Cultural Food Craving in Gender Transition

This week we are featuring work from students in Val Ryan’s class The Science of Food and Cooking (MET ML619). Today’s post comes from Michelle Samuels.

Craving pickles is a commonly reported experience among transgender women and other transfeminine people undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The commonly held explanation involves a potential sodium-wasting side effect of one of the HRT drugs, but this relationship has not been formally studied. Further, it remains unclear why pickles have taken primacy as the object of this common craving.

To better understand this relationship between transfeminine people and pickles, I have examined existing research on other hormone shifts and food cravings, hunted down early mentions of the phenomenon, and conducted short, informal interviews with transgender and cisgender peers and with the primary care physician who has overseen my own medical transition.

In the end, I have concluded that some transfeminine people experience food cravings during hormonal transition, some of these cravings are from HRT-related sodium wasting, and this sodium-wasting sometimes leads to craving pickles over other salty foods—but that this alone does not account for the communal narrative about pickles and cravings.

Instead, it appears that the pickle has taken on a complex symbolic importance: as a common experience in a community in need of commonality; as an expectation and touchstone for those undergoing an uncommon, understudied, and underrepresented medical process; and, perhaps above all else, as validation.

1) Pickles and Transfems, an Introduction

In 2017, Jennifer Finney Boylan, a transgender author, received a jar of pickles from a fan at a book signing. “As the night wound down, a transgender woman approached the signing table and handed me an enormous jar full of kosher dills,” Boylan recalled two years later. “’I made you these pickles,’ she said somberly, ‘in solidarity.’”

Boylan was baffled, but quickly caught up:

Apparently the meme began because transgender women in transition often take the drug spironolactone, an anti-androgen that has the side effect of making people crave sodium. Which is where the pickles come in; if it’s salt you’re after, pickles will definitely do the trick. (Boylan 2019)

First, what is spironolactone, and how might it contribute to pickle cravings?

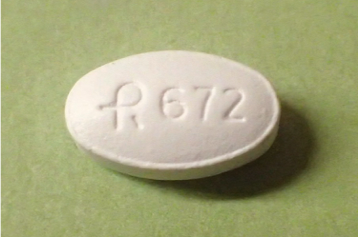

2) “Spiro”

Spironolactone, popularly called “spiro” in the trans community, is a diuretic most commonly used to lower blood pressure via its effect on the water- and salt-regulating hormone aldosterone, causing the body to absorb less sodium and more potassium. (When I began taking spiro, I was told to limit my intake of potassium-rich foods; why has pickle craving taken off as a trans symbol, but not banana avoidance?)

Aldosterone is also one of the androgens, a set of hormones associated with “masculine” characteristics in hair distribution, skin texture, muscle mass, genital formation and function, and other areas. In the 1970s, doctors treating hypertension in cisgender women noted that spiro also reduced their androgen levels, leading to spiro becoming a standard medication for treating the symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Ober and Hennessy 1978). With the discovery that spiro in doses of 100mg daily and above can also directly inhibit testosterone production, the drug became a standard part of transfeminine HRT (Tomlins 2019).

Transgender medicine has long operated outside of the medical mainstream (Safer and Tangpricha 2008), so there is limited research and understanding of the finer points, such as food cravings. However, a patient handbook on PCOS notes that patients taking spiro should be wary of sodium loss, and recommends “eating saltine crackers, a small sour pickle, or any other salty snack before exercise.” (Futterweit and Ryan 2006, 181; emphasis added)

Pickles may “do the trick” for the sodium-craving side effect of spironolactone, but so might saltines, potato chips, or salted peanuts. Why, then, has the pickle become so central that a fan would somberly present a jar to Boylan?

3) The Research: Hormonal Shifts and Food Cravings

Could other changes from HRT also contribute to food cravings, perhaps giving pickles an edge with their qualities beyond saltiness, such as sourness?

Again, while transgender food cravings are unstudied, there is some research available for cisgender women.

In a review of 14 studies of taste and preference in pregnant women, Weenan et al. found that many women experienced some change in their sense of taste during pregnancy, including a decrease in the perception of saltiness later in pregnancy, and an increase in liking and consuming salty snacks in the second and third trimesters. The review also identified a higher threshold for bitterness in the first trimester and a preference for sweet snacks in the second trimester, but no significant or consistent change in perception or preference for sourness (Weenan 2018), and so, no answers for the popular trope of pregnant women craving pickles, when, again, saltines would do the trick.

Faas et al. trace hormonal appetite changes to estrogen and progesterone levels during pregnancy and in the ovarian cycle: Appetite decreases when ovulation boosts estrogen, and increases during the high-progesterone luteal phase (i.e., the time between ovulation and the beginning of menstruation) as well as during pregnancy (Faas 2009). Transfeminine HRT almost always includes estrogen, and in some cases, includes progesterone to aid in breast development and counter some cardiovascular, cancer, and bone density risks of estrogen and reduced testosterone (Prior 2018).

So, based on the findings of Faas et al., and perhaps of Weenan et al. as well, the usual transfeminine HRT cocktail containing estrogen much more often than progesterone would reduce appetite and associated cravings. In other words, the apparent parallels in food cravings in HRT and in the ovarian cycle and pregnancy are not so parallel after all. However, these parallels may still have a cultural role in the experience of transfeminine HRT; more on this later.

The diuretic side effects of spiro, then, remain the best physiological explanation for pickle cravings in transfeminine HRT. However, as discussed above, spiro does not explain why pickles have surpassed other salty foods to represent this phenomenon.

4) Let’s Have a Kiki: A Qualitative Survey of Trans and Cis Hormone-Related Food Cravings

I contacted my own primary care physician, Dr. Joseph Baker at Fenway Community Health Center in Boston, who has overseen my entire medical transition, and asked him about cravings for salty foods, or pickles in particular, in patients undergoing transfeminine HRT. “I have observed some anecdotes,” he said. “Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find any reliable sources of information on food cravings with hormone therapy. This may be an area that needs to be investigated further.” He also checked in with colleagues, who similarly noted hearing anecdotes about food cravings and increased overall appetite, but no published research.

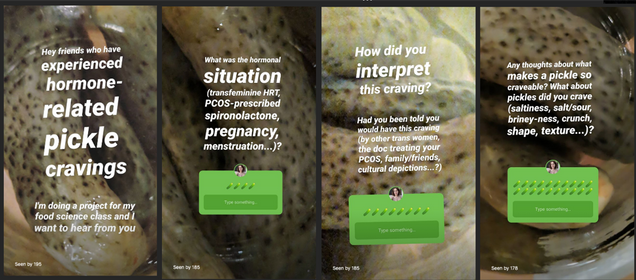

To at least gather more anecdotes, I conducted an informal, qualitative survey of friends and acquaintances to gather reports of cravings associated with any and all hormonal shifts. I used Instagram to conduct this survey, with initial questions on Instagram Stories and follow-up questions in Instagram direct messages, in February and March of 2020.

Respondents included four cisgender women, six nonbinary transmasculine people, and five people across the transfeminine spectrum (two of them identifying as trans women), all in their 20s and 30s; one transgender woman was African American, one cisgender woman was Asian American, and the rest were white. They shared experiences during both transfeminine and transmasculine hormonal transition, pregnancy, and ovarian cycles. Because of varying levels of comfort sharing such personal information, here I identify all respondents by their initials for consistency. See the Supplement after the Works Cited section at the end of this paper for all of the responses.

Consistent with the research on pregnancy described in the previous section, two cisgender women and one nonbinary transmasculine person reported pregnancy-related pickle cravings. “I already loved pickles, it just intensified—also kimchi, sauerkraut, etc.,” said AB, a cisgender mother of two. JC, another cisgender mother of two, reported that she craved pickles because she craved salt, but at the same time pickles were “also kind of fresh? Refreshing?” WR, a transmasculine person who had been pregnant, raised the possibility that their own pickle craving came in part from cultural depictions of pregnancy.

Respondents also reported pickle cravings linked with their ovarian cycles: AE, a cisgender woman, reported craving pickles during ovulation, while CF, a nonbinary transmasculine person, said, “Usually [I crave pickles] as a, ‘Damn, I’m going to get my period I guess.’ Pickle dinner is a near ritual thing when I’m PMSing.” Because AE’s experience is of a craving during an increase in estrogen, while CF’s is during an increase in progesterone, it is difficult to draw any physiological conclusions from these reports.

Surprisingly, several transmasculine people reported an increased desire for pickles after beginning to take testosterone, popularly referred to as “T.” AG said, “My boyfriend and I are both trans masc on T and crave salty vinegar things more than anything now. I didn’t think much of it until he [my boyfriend] brought it up as a hormonal possibility.” Likewise, GJ, who began taking T four or five years ago, said, “I’m not sure, but within that time I definitely noticed I started to crave salty things more, especially pickles.” While transmasculine people may experience some suggestible craving from hearing that other transgender people crave pickles, AG’s experience of a craving beginning before hearing about the trans-pickle connection raises the possibility that some other mechanism may also be at play for individuals taking testosterone, which could also be explored by looking at cisgender men with naturally and medically lowered or raised testosterone levels.

Most interesting for the purposes of this paper, the transfeminine respondents showed no consistency in cravings, with two reporting cravings consistent or semi-consistent with the narrative and three reporting no cravings.

DT, a nonbinary transfeminine person, said, “It was constant for the first six months for me, then kind of died off, and now I don’t crave [pickles].” Those six months began around the time DT started taking estrogen in the form of estradiol, at 2mg/day, when they had already been on spiro at 100mg/day for two months; both dosages were doubled in September, with no reported change in pickle cravings until three months later.

SS, a transgender woman who has been on the same 400mg spiro and 4mg estradiol dose as DT for the last year, reported craving “pickles, capers, and olives.

I think it’s the brine. I’ve always loved pickles, but [now also crave] olives! I have no idea [why], I think it might just be the salty/vinegar taste of the brine, but olives leave this slightly slick mouth feel. Before HRT I couldn’t stand them [olives], but now I can eat a whole jar without hesitation. It feels like I have no self control, I find myself eating things I literally couldn’t stand before, and binging whatever craving comes to mind.

SS’s experience raises interesting questions about the physiological nature of HRT-related cravings; while she reported an increased desire for salt, she also notes a change in liking olives, which she previously disliked because of their oiliness.

On the other hand, the other three transfeminine respondents reported no noticeable change in food preferences or cravings associated with HRT. These three non-cravers included two nonbinary transfems and one trans woman, and were within the same age range as the two transfems who did report cravings.

The five transfeminine respondents reported varying feelings about the pickle craving narrative and experiencing or not experiencing such cravings. “It felt a little validating?” said DT. “I think it was one of those things where it validated my identity as a trans femme person and made me feel like I was being let into a secret club. I knew it was a shared experience among trans femme people and that felt really important to me.”

KG, who reported slowly increasing doses of spiro and estradiol from the same starting dose as DT, echoed this sense of a “club” in describing not experiencing the craving herself:

I heard about this a lot but never experienced it…. I guess I didn’t really mind; I never felt like my gender aligned with what I heard or saw from the broader transfeminine community… and I still don’t, to this day, which is both empowering around my own identity and in some ways feels othering.

Similarly, KT, a transgender woman, did not notice a change from HRT—noting she has always loved pickles, and drank “sips of the juice” even before starting HRT. “I wondered if the whole pickle craving thing was kind of a joke or a social psychological effect,” she said.

The range of experiences reported by the respondents, cis and trans, transfeminine and transmasculine, show the complexity of hormonal changes in human bodies and their relationships with food cravings and preferences. To elucidate these complexities, further research could draw from a larger pool of respondents, with greater cultural, racial/ethnic, and age diversity, and gather prospective data rather than relying on respondents’ recall.

The responses also demonstrate the importance of a social element to the idea of pickle cravings among transgender people, including a sense of validation and being let into or finding oneself outside of a “club,” with even some transmasculine people—perhaps having heard generally about transgender pickle cravings but not the spiro explanation specific to transfeminine people—reporting sharing the experience.

5) Trans Archeology and the Evolution of HRT Cravings

The current state of the transfeminine pickle phenomenon appears somewhat muddled, with many trans people reporting familiarity with it, but only some describing actually experiencing it.

However, the origins and underlying mechanisms of the phenomenon may become clearer by looking to the past. Here, we discover what may be the strongest piece of evidence suggesting the transfeminine pickle phenomenon is not strictly physiological: The pickle only rose to prominence within the last decade.

In her seminal 2007 memoir/manifesto Whipping Girl, Julia Serano describes a strong craving after starting HRT—not for pickles, or any other salty food, but rather for eggs:

I immediately attributed this to the hormones until other trans women told me that they never had similar cravings. So perhaps that was an effect of the hormones only I had. Or maybe I was going through an ‘egg phase’ that just so happened to coincide with the start of my hormone therapy. Hence, the problem: Not only can hormones affect individuals differently, but we sometimes attribute coincidences to them and project our own expectations onto them. (Serano 2007, 66–67)

What Serano describes is the frustration with a common refrain in trans medicine: “Mileage may vary.” Myriad individual factors influence the effects and experiences of HRT, as well as hair removal, surgeries, social transition, and so on. Add to this the lack of accurate popular representation of these processes and the scarcity of “elders” who have gone before; no wonder trans people would grab on to any commonly-reported touchstone, any narrative of what to expect, even one as trivial as craving pickles.

The earliest mention of transfeminine pickle cravings that I could find using English-language Google is from a 2010 message board (much has been written on the astonishing difference the last ten years has made in trans culture and the complexity and brevity of trans “generations,” see, e.g., Lavery 2019).

The original poster asks:

why do I crave salt so much….?

Is it the spiros highish doage that does it? Or do I just like salt…

I feel like I’m never satisfied with it but I always have way too much….

I’ll put sea salt on my had and freaking lick it off…

WWHHHHYYYY? ( “Spiro and Salt Cravings?” 2010; sic)

She is answered by a dozen other trans women, all echoing the same explanation: Spiro is a diuretic.

However, pickles are just one of many foods discussed in the ensuing thread. One responder writes: “Mmmmm, kosher dill pickles, olives, pickled herring, bacon, miso soup, those crazy expensive sweet and salty granola bars… the list goes on and on.” Another reports loving olives stuffed with anchovies. A third respondent is hopefully joking when she writes, “Don’t eat rock salt unless it’s actual salt, I nibbled a chunk of some chemical labeled ‘de-icer’ and it was vile and not fit for woman nor beast” (ibid).

This message board conversation from 2010 shows that the transfeminine community was already familiar with the sodium-loss side effect of spiro, but that pickles had not yet taken primacy. We have to assume, then, that pickles have taken primacy for cultural, rather than physiological, reasons.

6) Chocolate, and an Answer?

It is a tangent in the 2010 thread about salt cravings that may offer the most insight—a tangent about chocolate.

The tangent begins with one poster writing, “chocolate is amazing. I eat it and I can feel the rush all over my body. Mmmmm, chocolate! Orgasmic! It’s not just the taste, but how it makes you feel… I don’t know how to explain that. LOL” (“Spiro and Salt Cravings?” 2010; sic).

What is notable about this is not so much that she reports craving chocolate, but the emphatic and decidedly feminine way that she reports a craving especially common among American women. This craving is likely cultural, given that the gender difference in chocolate craving in other countries is much narrower (Hormes 2014).

Here, we see food craving as gender performance, with the poster enacting and emphasizing her female identity through a culturally gendered, commonly-reported food craving (for more on gender performance, see Butler 2011). Considering that women are much more likely than men to report any kind of food craving, at 97% percent of women compared to only 68% percent of men by one estimate (Weingarten and Elston 1990), it seems appropriate that food cravings would hold a special, validating importance for trans women and other transfems. This would seem to explain why, of all of the experiences associated with HRT, a food craving would rise to the top as a symbol, unifying cultural touchstone, and meme.

So, why the pickle? Of the salty food cravings, it is the one most popularly associated in this country with pregnancy (for more on the rise of the “pickles and ice cream” narrative see Onion 2018), making it perhaps the most powerfully feminine of all already-feminine food cravings. The pickle is also meme-friendly, with a long association—via the absurd and the phallic—with drag culture (see, most famously, Rubnitz 1989).

7) Conclusion

As we have seen, pickle cravings in transfeminine HRT have a likely physiological cause in the salt craving effect of the diuretic spironolactone. However, while sodium deficiency from spiro can contribute to craving any number of salty foods, the common narrative about the shared pickle craving experience is fairly new, arising within the last decade.

Rather than a purely physiological phenomenon, this craving has gained prominence in the trans community as a shared touchstone experience, an expectation in a still-mysterious medical process, and as a validation of gender identity through the feminine associations of food craving in general and of pregnancy cravings for pickles in particular. Throw the comic nature of the fermented cucumber into the mix, and the pickle is the perfect candidate for a unique role for a food. Perhaps no other community has, or has quite the same need for, a food role like the craving of the transfeminine community for pickles.

Works Cited

Boylan, Jennifer Finney. 2019. “Why the Pickle Became a Symbol of Transgender Rights.” New York Times, September 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/18/opinion/transgender-rights-pickle-boylan.html.

Butler, Judith. 2011. “Judith Butler: Your Behavior Creates Your Gender | Big Think.” June 6, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bo7o2LYATDc

Faas, Marijke M., Barbro N. Melgert, and Paul de Vos. 2009. “A Brief Review on How Pregnancy and Sex Hormones Interfere with Taste and Food Intake.” Chemosensory Perception 3 (2010): 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-009-9061-5

Futterweit, Walter, and George Ryan. 2006. A Patient’s Guide to PCOS: Understanding—and Reversing—Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. New York City: Henry Holt and Company.

Hormes, Julia M., Natalia C.Orloffa, and Alix Timkob. 2014. “Chocolate Craving and Disordered Eating. Beyond the Gender Divide?” Appetite 83 (December): 185-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.018

Lavery, Grace. 2019. “Trans Kids These Days.” April 15, 2019. https://grace.substack.com/p/trans-kids-these-days

Ober, K. Patrick, and John F. Hennessy. 1978. “Spironolactone Therapy for Hirsutism in a Hyperandrogenic Woman.” Annals of Internal Medicine 89, no. 5 (Part 1): 643-644. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-89-5-643

Onion, Rebecca. 2018. “Hysterical Cravings.” Slate, April 18, 2018. https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/04/pickles-and-ice-cream-how-the-crazy-combo-became-iconic-for-pregnant-women.html

Prior, Jerilynn C. 2019. “Progesterone Is Important for Transgender Women’s Therapy—Applying Evidence for the Benefits of Progesterone in Ciswomen.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 104, no. 4 (April): 1181–1186. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-01777

Rubnitz, Tom. 1989. “Pickle Surprise.” Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N733Ofj2cVQ

Safer, Joshua, and Vin Tangpricha. 2008. “Out of the Shadows: It is Time to Mainstream Treatment for Transgender Patients.” Endocrine Practice 14, no. 2 (March): 248-250.

Serano, Julia. 2007. Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, 2nd ed. (2016) New York City: Basic Books.

“Spiro and Salt Cravings?” Susan’s Place, January 24, 2010. https://www.susans.org/forums/index.php?topic=71424.0

Tomlins, Louise. 2019. “Prescribing for Transgender Patients.” Australian Prescriber 42, no. 1 (February): 10–13. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2019.003

Weenan, Hugo, Annemarie Olsen, Evangelia Nanou, Esmée Moreau, Smita Nambiar, Carel Vereijken, and Leilani Muhardi. 2018. “Changes in Taste Threshold, Perceived Intensity, Liking, and Preference in Pregnant Women: A Literature Review.” Chemosensory Perception 12 (2019): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-018-9246-x

Weingarten, Harvey P., and Dawn Elston. 1990. “The Phenomenology of Food Cravings.” Appetite 15, no. 3 (December): 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(90)90023-2

Supplement 1: Results of a Qualitative Survey of Trans and Cis Hormone-Related Food Cravings

AB, cisgender woman: “Pregnancy! I already loved pickles, it just intensified. Also kimchi, sauerkraut, etc.”

AE, cisgender woman: “Ovulation! Need salt/sour to make good eggs.”

AG, nonbinary transmasculine: said, “My boyfriend and I are both trans masc on T and crave salty vinegar things more than anything now. I didn’t think much of it until he brought it up as a hormonal possibility. Being Jewish is an extra layer to this because if it’s not a crisp dill I’m not into it lololol.”

CF, nonbinary transmasculine: “Usually [I crave pickles] as a ‘Damn, I’m going to get my period I guess.’ Pickle dinner is a near ritual thing when I’m PMSing.”

DT nonbinary transfeminine: “It was constant for the first six months for me, then kind of died off, and now I don’t crave [pickles]. It started about a month or so in. I started spiro in May of 2019, and was on 100mg/day. Estradiol started in July 2019, 2mg/day. They both got doubled in September. I’d say cravings started over the summer, sometime just before starting estradiol, and then continued through the end of the year. I 100% had heard of it [the pickle craving]. [Experiencing] it felt a little validating? I think it was one of those things where it validated my identity as a trans femme person and made me feel like I was being let into a secret club. I knew it was a shared experience among trans femme people and that felt really important to me. I haven’t felt that craving in a while, though I do still keep a jar of pickles in my fridge just in case…”

EL, nonbinary transmasculine: “I’m transmasc so I know I’m not the target, but I’m also an RN and we talked about the cravings when I was in school. We were literally told to provide clients with salty snacks, specifically pickles. I went to school at University of South Carolina, they have a campus in Greenville that I attended. We’d discussed spiro in my pharmacology class but it was in a general medical/surgical class that we went over real life side effects. The professor wanted us making care plans for patients on spiro, and the two patient scenarios we were given were for transfem HRT and congestive heart failure. I remember it really well because that was the first time we ever discussed any kind of queer health other than in psych class.”

GJ, nonbinary transmasculine: “Briney crunch [is the appeal]. I don’t know if it’s HRT or what but I crave salty pickled things all the time the past few years. Well, I started hormones four or five years ago, so I’m not sure. But within that time I definitely noticed I started to crave salty things more, especially pickles. Official start date [i.e. age at beginning of HRT] is complicated but let’s just say 26.”

JC, cisgender woman: “Pregnancy made me want something salty all the time. And pickles were salty but also kind of fresh? Refreshing?”

KG, transfeminine: “You know, I heard about this a lot but never experienced it. I’ve always loved pickles, so there’s that, but I never experienced any cravings. I guess I didn’t really mind; I never felt like my gender aligned with what I heard or saw from the broader transfeminine community—which at the time was primarily via Reddit—and I still don’t, to this day, which is both empowering around my own identity and in some ways feels othering. I started HRT when I was 25 and a half (actually on my half birthday!). I started quite low, 100mg spironolactone and 2mg of estradiol (orally) and slowly increased the dosages over a few months. It eventually settled at 6mg estradiol. My spiro dosage had increased to 200mg but I had many issues with dizziness and blacking out, but after two years, I wasn’t feeling enough had changed so my doctor (after a lot of “consulting with colleagues”) increased my HRT dosage to 8mg sublingually, which is what it still is today.

KR, cisgender woman: “I have PCOS but haven’t been on [spiro]. But even when I’ve taken things to ramp up estrogen and stifle T (birth control and/or supplements), I haven’t really had cravings I don’t think. I’ve had PCOS since I was 11, diagnosed at 22 and haven’t taken birth control since then. I take inositol, it works.”

KT, transgender woman: “I’ve always loved pickles enough to drink sips of the juice. I honestly probably did that before starting HRT. I’m on 6mg estradiol a day, and 100mg spironolactone a day which started (at much smaller dosages) in July of 2017, when I was 24 years old. I’ve also been on progesterone (100mg) for about a year now, kinda on and off as I figure out if it’s right for me. I feel and have felt fine about it [not experiencing cravings]. I’ve never put too much thought into it. I wondered if the whole pickle craving thing was kind of a joke or a social psychological effect. Everybody’s body is different, though! Happy for everyone who gets those pickle cravings. Pickles are amazing, and more trans folk eating pickles warms this Jewish trans femme’s heart! I think I might go buy a jar of pickles now.”

LS, nonbinary transfeminine: “I don’t think that I ever experienced this phenomenon, at least not in a way that I noticed. I maybe first heard about it when I read Whipping Girl in the months leading up to starting HRT. I can’t remember if Serano actually mentions the salt/pickle craving, but she discusses the effects of HRT and that was my primer for expectations. [I felt] indifferent I guess [about not experiencing any cravings]. I’ve always liked pickles and always had a preference for salty/savory over sweet. My starting dose when I was 25 was maybe 2mg of estradiol a day and went up to 6mg. I did that with 200mg spiro for a few years, and introduced progesterone about a year into HRT. I’m now on 0.5ml estradiol injected every other week and 200mg of progesterone a day, and no anti-androgrens.”

SS, transgender woman: “Pickles, capers, and olives. I think it’s the brine. I’ve always loved pickles, but [now also crave] olives! I have no idea [why], I think it might just be the salty/vinegar taste of the brine, but olives leave this slightly slick mouth feel. Before HRT I couldn’t stand them [olives], but now I can eat a whole jar without hesitation. It feels like I have no self control, I find myself eating thing I literally couldn’t stand before, and binging whatever craving comes to mind. I’m on 200mg spiro, 4mg estro, and I started when I was 23, which was a year and a few months ago.”

WR, nonbinary transmasculine: “Pregnancy. Cultural depictions, probably. Also nostalgia/comfort? I ate pickles a lot as a kid. Crunch plus brine plus salt plus tang [was the appeal].”