Home

Psychopathy and Multiple Murderers: Surviving trauma? Or letting trauma survive?

When we think of the trauma of psychopaths and multiple murderers we often default to thinking of their victims. In reality, the psychopath and/or multiple murderer was created through trauma, bringing trauma into this discourse long before their eventual victims existed. The psychopath/multiple murderer is a victim as well, just in a different way.

Does this justify their behavior in any way and make it easier for anyone affected? Absolutely not.

A psychopath and multiple murderer undoubtedly leave a trail of trauma behind for their victims and their loved ones/community, and no less attention or validation should be given to the victims. But a challenging point of view is to also consider how the offender was the victim before they committed a criminal act. The offender acts because of the trauma they have experienced, and then through their actions creating a different type of trauma for someone else.

The issues the offender faces are not justifications or defenses for their acts, but instead explanations for their behavior. It is important to identify the causes for a behavior to understand how to prevent it from reoccurring and to provide effective interventions. The intersection of trauma, the criminal justice system, and psychopathy are heavily intertwined when psychopaths and/or multiple murderers commit criminal acts that call for punishment and rehabilitation or ongoing treatment.

We will focus on a few case studies, albeit extreme ones, but prime examples of what a multiple murderer’s and/or psychopath’s background generally can look like and how the magnitude of someone’s life experience can influence their behavior. The main case study, the life story of Jeffrey Dahmer, mirrors other similar notable murderers, such as Charles Manson and Aileen Wuornos. One thing they all had in common was their experience of chronic childhood neglect and/or abuse. How can we expect someone to know how to care for themselves or others appropriately if they were cared for improperly their whole life, or just never cared for at all?

When they were not fighting, Dahmer’s father was preoccupied with his chemistry studies, while his mother was consumed by her hypochondria and depression, which entailed suicide attempts, hospitalizations, and symptoms in the home, such as not touching Dahmer at all. His parents were focused on anything other than Dahmer it seems, especially after his younger brother was born, when even more attention was displaced from him. This trend followed him throughout his lifetime when his parents finalized their divorce and his family moved out of the house, leaving him behind (Janos, 2021) and also when his parents took no action after he was sexually abused by a neighborhood boy (Higgs, 2021, pp. 10-11). In the midst of all these factors building up, Dahmer is also learning how to experiment with dead animals from his chemist father (Editors, 2021) while constantly trying to navigate his overwhelming sexual feelings. This translates later in life when he felt sexual stimulation in opening up his victims and experimenting on them. He would kill his victims not out of rage, but so they were not able to abandon him (Strubel, 2007) (Dickinson, 1992); he was able to accomplish this with the skills he learned from his father and what he witnessed through his parents’ behaviors (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, pp. 45, 49, 58, 83, 145, & 147). The neglect from his parents compounded by his lack of friends influenced by his poor social skills, his learned interests, and his family’s frequent moving did him no favors developmentally and heavily contributed to his behavior and crimes.

In all fairness, there is no known cure or treatment for multiple murderers and/or psychopathy and there is very little research into physiological and genetic causes for them. This leaves us to only consider developmental and learning/situational factors, while guessing how any biological factors have impacted these offenders. In analyzing one case biologically to give some perspective, Dahmer had a hernia surgery at four years old where his affect changed for the worse afterward (Editors, 2021) and his mother had a reportedly difficult pregnancy with him (Casey, et al.). He was exposed to heavy amounts of psychiatric and hormonal medication in the womb as well (Dickinson, 1992) which could influence antisocial behavior and behavioral issues along with socioemotional problems, diminished cognitive development, and emotional dysregulation (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 48) .We are unsure how these biological factors influenced him specifically, but the point is that they could have in some capacity. From self-reporting, Dahmer disclosed that he had an uncontrollable libido (Janos 2021) (Higgs, 2021, p. 14), which is biological, but since he did not receive treatment for it or education on it, it can also be considered a learning factor. The same goes for his alcoholism; from the age of fourteen he drank heavily daily through his adolescence and young adulthood (Editors, 2021), which could have resulted in brain changes directly impacting his brain functioning (Hawes, et al., 2015, pp. 1-2) (Bartol & Bartol, 2021, p. 26) (Less, et al., 2020, p. 4). Although it is a learning factor, it could have turned into a biological factor too if it altered his anatomy. We will never know, since he was cremated and there was no research ever done on his body, pre or postmortem (Sullivan, 2018).

To compare Dahmer’s case to other similar offenders who murdered multiple times, Manson and Wuornos also experienced developmental trauma. Wuornos’ story from the get-go sets her up for failure. After her father died by suicide in jail after being convicted of child molestation, her mother abandoned her. Wuornos’ alcoholic grandparents abused her physically and sexually in addition to the sexual relations she had with her brother. She was eventually forced out of her home and rendered homeless in her teenage years, when she also gave birth to a son who she did not raise. To survive Wuornos worked as a prostitute most of her life and eventually killed multiple men that she met while prostituting and hitch hiking (Shelton, 2021). It can be deduced that Wuornos’ adult behavior is a result of many types of traumas she endured throughout her lifetime and a lack of any significant attachment from that trauma.

Similarly to Wuornos, Manson never met his father and his mother abandoned him for long periods of time in his childhood. She struggled with alcoholism, criminal behavior, and maintaining relationships; at one point she was incarcerated in his youth and he stayed with other family during that time who doled out humiliating punishments to him. Manson started engaging in socially inappropriate and criminal behavior from a young age when he had no oversight and was in and out of reformatory schools, one of which he was raped at. After that he was caught sexually assaulting others multiple times and continued engaging in criminal behavior, escalating the severity and frequency of the behavior over time until he is caught facilitating murders through a cult where he coerced others to carry out crimes for him, just like he did in school where he would influence his peers to act out. He also had poor intellectual functioning as a result of hardly any education. Yet he was able to use drugs to coerce others and feed into his delusions and worsen the symptoms of his mental illnesses (Charlesmanson.com). At this point we can see a pattern between all three murderers and how their childhood was riddled with lack of attachment, affection, education, appropriate social skills, survival needs, and support. Just as we cannot expect a flower to grow or flourish without being cared for with proper nutrients and conditions, we can not expect the same for humans either.

Without invalidating victims’ trauma, it is crucial that we also consider the trauma of the offending. Without understanding the factors for why someone behaves in the way that they do, there is no way to fix the problem. While there is no research to fully answer the origins of psychopathy, it is imperative that we acknowledge how life experiences affect us. In these cases, every offender experienced chronic and severe abuse and/or neglect. They were not equipped with the proper tools to self-care or to care for others. In their own ways they were stunted developmentally mentally, socially, and emotionally (and in some cases intellectually). It is invaluable to recognize how behavior can be created and learned, so providing treatment and guidance at young ages for children who are identified as trauma affected is a good step in working toward preventing psychopathy and other personality disorders. Dahmer expressed that he experienced compulsions and could not control his actions. Bartol & Bartol (2021) explain how self-regulation and neuroplasticity can work in conjunction to promote executive functioning (pp. 71-72). Even if it is simple self-care like identifying positive, healthy, appropriate hobbies while providing survival needs and emotional nourishment. If in Dahmer’s, Manson’s, and Wuornos’ lifetime they were given opportunities to understand how to take care of themselves and how to appropriately regulate their emotions, mental state, and physical state, their fate and the fate of their victims could be very different.

References

Bartol, C.R. & Bartol, A.M. (2021). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (12th Ed.). Pearson Education, Inc.

Casey, V., Clagett, L., Allen, B., Williams, L., Duff, T., Guthrie, J., Hanger, C., Glinisty, J., Harrigan, K., Hoeflinger, A. J., Logan, M., McGlothlin, J., Sebastian, S., Michlik, K., Ray, R., Records, M., Simpson, H., Smith, S., Bratton, A., … Tinsley, K. (n.d.). Jeffrey Dahmer. Department of Psychology Radford University. http://maamodt.asp.radford.edu/Psyc%20405/serial%20killers/Dahmer,%20Jeff.htm

CharlesManson.com. (2020). Retrieved August 15, 2022, from charlesmanson.com

Dickinson, C. (1992, August 27). The inner life of a psycho killer. The Chicago Reader. chicahttps://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/the-inner-life-of-a-psycho-killer/goreader

Editors. (2021, August 13). Jeffrey Dahmer biography. Biography.com. https://www.biography.com/crime-figure/jeffrey-dahmer

Elawtalk.(2022). Forensic psychology vs. criminal psychology: What’s the difference? [Photograph]. https://elawtalk.com/forensic-psychology-vs-criminal-psychology/

Hawes, S. W., Crane, C. A., Henderson, C. E., Mulvey, E. P., Schubert, C. A., & Pardini, D. A. (2015). Codevelopment of psychopathic features and alcohol use during emerging adulthood: Disaggregating between- and within-person change. Journal of abnormal psychology, 124(3), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000075

Higgs, T. (2021, December). Jeffrey Dahmer: Psychopathy and neglect. All Regis University Theses. https://epublications.regis.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1240&context=theses

Janos, A. (2021, August 17). Jeffrey Dahmer’s childhood: A pail of animal bones was his toy rattle. A&E TV. https://www.aetv.com/real-crime/jeffrey-dahmer-childhood-serial-killer-cannibal-bones

Less, B., Meredith, L.R., Kirkland, A. E., Bryant, B. E., & Squeglia, L.M. (2020, May 01). Effect of alcohol use on the adolescent behavior and brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav., 192, 172906. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172906

Matthieu. (2022). Iceberg with its visible and underwater or submerged parts floating in the ocean. 3D rendering illustration [Photograph]. Adobe Stock. https://stock.adobe.com/sk/search/images?k=underwater+iceberg&asset_id=369564134

Shelton, J. (2021, September 23). Haunting stories from Aileen Wuornos’s traumatic childhood. Ranker. https://www.ranker.com/list/aileen-wuornos-childhood-facts/jacob-shelton

Strubel, A. (2007, December 10). Jeffrey Dahmer: His complicated, comorbid psychopathologies and treatment implications. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 5(1). http://www.nspb.net/index.php/nspb/article/view/24

Sullivan, C. (2018, July 13). Jeffrey Dahmer biography: The cannibal killer. Biographics.org. https://biographics.org/jeffrey-dahmer-biography-the-cannibal-killer/

Walden University. (2022). Forensic Psychology at a glance [Photograph]. https://www.waldenu.edu/programs/psychology/resource/forensic-psychology-at-a-glance

The Aftermath of Solitary Confinement- A Family Experience

Research indicates that the effect of solitary confinement can be lethal. Though only 6%-8% of the prison's population is in restricted housing, they account for half of those who die by suicide. Dr. Grassian believes one may develop a specific syndrome due to the effects. "It is characterized by a progressive inability to tolerate ordinary things, such as the sound of plumbing; hallucinations and illusions; severe panic attacks; difficulties with thinking, concentration, and memory; obsessive, sometimes harmful thoughts; paranoia" (Grassian, 2006). The focus is usually on the psychological damage of the inmate. However, what happens when that inmate is released directly from solitary confinement into the community? These inmates tend to withdraw, remain aloof or seek social invisibility socially, and could not be more dysfunctional in family settings where closeness and interdependency are needed (Haney, 2001). There is little to no count of that effect after an inmate is released from incarceration into the community. Here is my story….

My oldest brother, Virgilio, was 17 years old when he was first incarcerated for petty theft of auto parts. Back in 2009, it was the thing among young men in our neighborhoods to do illegal car racing and steal each other car parts. One day, he got caught, and as a result, he was arrested and put on probation for a year. Three years later, he was arrested again for domestic violence ( a verbal dispute). During this time, though, it was different. Immigration and Customs Enforcement put a hold on him within hours of being arrested (which means he could get deported for violating the USA laws). A day after incarceration, he got into a fight and was put in solitary confinement for two months. During this time, he was not allowed to have visitors or receive letters from his loved ones. He was entitled to one phone call every few days during his hour of recreation, usually after 9 pm. Every day I waited for his call, he sounded depressed, and the things he would say did not make sense. Our family paid for a psychological evaluation to use it as evidence and perhaps grant leniency. Following a doctor's recommendation, a judge granted my brother to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital instead of incarceration for further evaluation. We were happy, thinking he would get better, but his mental state was different. I remember how my family and I would cry in the car whenever we visited him. The sadness in my mother's eye made the pain even worst.

At 23, my brother was diagnosed with Bipolar I Disordered. He was released back to jail to await a decision from Immigration. he was put on heavy medications by a Riverside Regional Jail psychiatrist. Even though he was under medication, he was still not "normal." It became harder to converse with him or get him to express how he was feeling during this time. We went for two weeks without hearing from him. I went to Riverside Regional Jail to get information and was advised that he was put in solitary confinement. I asked when he would get released, and the lady said, "I am not sure; he will call you when he gets out." For the second time around, my brother was in solitary confinement, and this time it was for four months. My brother did five times the jail sentence he would have received for domestic violence if found guilty. He was incarcerated for one year, and within that year, he did a total of 6 months in solitary confinement.

We kept fighting for a release. Finally, however, during his last court hearing at an Immigration court, the judge asked my brother if he had anything to say for himself, and I remember like it was yesterday, my brother said, "I can't; my mind will not let me speak, solitary confinement fucked me up, send me home ." The courtroom went silent; all you could hear was my mother weeping. A few days later, he called from an Immigration jail about five hours away from us and said that he had been transported the night before and was getting deported the next day.

He was deported to Dominican Republic (D.R.). Our home in the Dominican Republic looked utterly different; Virgilio used to put metal chains around the front and back door, and the door to his bedroom would be padlocked from the inside. The lady who took care of him left his food at the window because he refused to open his door. He would go days without eating or showering. He would not talk to any of us for weeks at a time. He used to put wood on the windows so it would be dark in the house. His room looked like a jail cell. He used to say that he heard voices and thought he would be harmed; My brother was mentally impaired after being released. Many would say that "he violated the law, that is what he gets" or "all immigrants violate the law, they do not deserve to be here"… I HAVE HEARD IT ALL! but where is the human element? Where is the 8th amendment? (cruel and unusual punishment). I will never say not to punish, but solitary confinement is a harsh punishment; it psychologically damages inmates and their families. Past forward 11 years and my brother is still not the same. He has mental breakdowns and cannot be around too many people. He cannot function. Due to his mental health, he is not able to obtain employment. He is not able to interact socially.

What is it being done by State officials?

In the state of New York, the Senate passed the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement Act (HALT) in 2021, which limits the use of segregated confinement for all incarcerated persons to 15 days; it implements alternative rehabilitative measures, including the creation of Residential Rehabilitation Units (RRU) (Ny State senate Bill S2836 2021). In addition, in 2021, the Virginia Department of Corrections (DOC) removed restrictive housing (solitary confinement) in Virginia's prisons. Instead, they created the Secure Diversionary Treatment Program, which diverts inmates with serious mental illnesses who are at risk of engaging in severe and disruptive incidents from a restrictive housing setting into a program where their unique needs are met and supported (Vadoc, 2021).

While solitary confinement affects an inmate mentally, physically, and emotionally for a lifetime, those same effects affect a whole family. My family suffered mentally, trying to figure out how to help my brother. My mother and father became physically and emotionally sick because they couldn't fathom the idea that their firstborn was not "normal." The criminal justice system affects the family as a whole. Getting therapy has helped me cope with what I was exposed to during my brother's incarceration. At 17, I was supposed to be on my way to college and live my life. Instead, I was trying to figure out why my brother looked dead, why he was not talking. It was a life-changing experience for all of us. Due to this experience, I decided to work in the criminal justice system, to make a difference" one family at a time," and to delegate changes within Community Corrections that would best fit the recently released clients.

Citations

Senate passes the 'halt' solitary confinement act. N.Y. State Senate. (2021, March 18). Retrieved August 15, 2022, from https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/senate-passes-halt-solitary-confinement-act

Haney, C. (2001, November 30). The psychological impact of incarceration: Implications for post-prison adjustment. ASPE. Retrieved August 15, 2022, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/psychological-impact-incarceration-implications-post-prison-adjustment-0

Vadoc - Virginia Doc completes removal of restrictive housing, WINS award from Southern Legislative Conference. Virginia DOC Completes Removal of Restrictive Housing, Wins Award from Southern Legislative Conference - Virginia Department of Corrections. (2021, July 22). Retrieved August 15, 2022, from https://vadoc.virginia.gov/news-press-releases/2021/virginia-doc-completes-removal-of-restrictive-housing-wins-award-from-southern-legislative-conference/

Stuart Grassian, Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement, 22 WASH. U. J. L. & POL'Y 325 (2006), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol22/iss1/24

Female Sex Offenders and Trauma

Sexual abuse is an extremely traumatic experience and in my work supervising sex offenders I too have been guilty of the common misconception that we all generally seem to have: when most people think of sex offenders, they envision men who sexually abuse women or young male or female victims. What is disconcerting however is the amount of sexual abuse based on reports by victims which has indicated that 40-60% of these offenses are committed by females, yet male offenders are prosecuted with much more frequency. What is even more alarming is that victims that have been sexually abused by both males and females report that the trauma of having been abused by a female has a more damaging impact, causing identity questions and feelings of betrayal. (Neofytou, 2022).

A large majority of the sexual assaults committed by females tend to go unreported for a variety of reasons: disbelief, embarrassment, and shame. Often the victims of sexual abuse and/or other childhood traumas themselves, their victims may be their own children or other young family members. Society views females are caring and nurturing, and it is therefore hard to even accept that these offenses even occur at their hands. In fact, at this point in time I only have one female sex offender on my caseload.

In the documentary Pervert Park, one of the residents of the trailer park, home to over 100 sex offenders, is a woman named Tracy, who was sexually abused by her father starting before the age of 5 and again later in her life as an adult. Tracy sexually abused her son when he was 11 years old, and sadly when her son was 16, he then in turn molested a 3-year-old boy. Not only does this show the cycle of trauma and abuse, it also serves to demonstrate the severe harm inflicted upon him as a child by his mother, a female sex offender.

All victims of sexual abuse need to have unfettered access to therapeutic counseling and trauma services not only to prevent revictimization but also to help prevent them from becoming the offenders of the future.

References

Köhncke, A; Barkfors, F. (2014). Final Cut for Real, & De Andra (Producers), & Barkfors, L. and Barkfors, F. (Directors). Pervert Park. [Video/DVD] DR Sales. Retrieved from https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/pervert-park

Neofytou, E. (2022, June). Childhood trauma history of female sex offenders: A systematic review. ScienceDirect. Sexologies, Volume 31, Issue 2. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1158136021000864#bbib0015

Institutional Betrayal Trauma and Peer Victimization

" [Institutional courage] is an institution’s commitment to seek the truth and engage in moral action, despite unpleasantness, risk, and short-term cost. It is a pledge to protect and care for those who depend on the institution. It is a compass oriented to the common good of individuals, the institution, and the world. It is a force that transforms institutions into more accountable, equitable, healthy places for everyone." - Center for Institutional Courage

Bullying as a form of aggressive behavior can elicit traumatic responses in many different populations. The most commonly addressed forms of bullying are school or childhood bullying and workplace peer victimization. Betrayal trauma theory addresses the traumas experienced by victims that are not always clinically recognized as traumatic. There are different types of betrayal trauma such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse committed by a caregiver, cultural betrayal, and institutional betrayal. Peer victimization, or bullying, can play a part in these experiences. Peer victimization on its own is exacerbated by institutional betrayal. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed by those in power at schools, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal; thus leading to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither institutional betrayal nor peer victimization are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. This has opened up research that questions the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD criteria and possible solutions. Institutional betrayal exacerbates peer victimization which shares symptomatology with PTSD; it should be considered for either inclusion of the PTSD diagnosis or grouped with other forms of childhood betrayal trauma to form a new diagnosis.

Peer Victimization and PTSD

Peer victimization in children, commonly called “school bullying,” takes place during sensitive periods of development. PTSD symptoms are often reported in victims of bullying (Idsoe et al., 2012). Bullying is a highly interpersonal event and it is known that experiencing an interpersonal trauma is linked with significantly higher levels of PTSD symptoms compared to other kinds of trauma (Lancaster et al., 2009 as cited in Idsoe et al., 2012). The relationship was originally established in workplace peer victimization, but is branching out towards school bullying. This is important to note because school bullying takes place during adolescence, an important developmental period of biopsychosocial systems. This presumes that bullying may have an adverse effect on biopsychosocial development.

Among the post-traumatic stress symptoms reported by people who have experienced bullying is dissociation. Dissociation is a very common symptom of PTSD. Gušić and colleagues (2016) conducted a study about different types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation. They found that emotional traumas, like bullying, showed stronger associations with dissociative experiences (DEs). Girls reported both higher levels of DEs and bullying. Betrayal traumas are also a kind of emotional trauma, and research shows that women experience more betrayal traumas than men do (Freyd, 2020). These associations between peer victimization and PTSD argue that the incidents of bullying can lead to symptoms that meet the clinical threshold of distress, for peer victimization to be officially recognized as an inciting traumatic event.

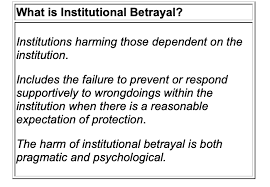

Institutional Betrayal

If peer victimization on its own results in post-traumatic stress symptoms and is perpetuated by academic institutions, then peer victimization is further complicated by institutional betrayal. Institutional betrayal is defined as transgressions perpetrated by an institution upon individuals dependent on that institution, including failure to prevent or respond supportively to transgressions by individuals committed within the context of the institution (Freyd, 2020). Institutional betrayal plays a part in peer victimization as most school bullying takes place in the context of the school by a peer also enrolled at that institution. This betrayal extends further into the institution when a victim’s disclosure is not responded to effectively.

There is relatively limited research on what characteristics define an adult’s response as “helpful or supportive” to an adolescent’s disclosure of bullying (Bjereld et al., 2019). First it is important to acknowledge that, yes, there are preventive and interventive strategies that produce positive outcomes. The problem is presented when school officials (assuming the victims’ parents have attempted effective communication, if they are aware of the bullying) fail to implement these strategic responses. These are similar to some of the responses that survivors of sexual assault receive, such as minimization or invalidation of the incident and a sense of abandonment when no steps are taken to address the issue once disclosed. Bjereld and colleagues’ (2019) study found that teachers often found a student’s disclosure as them misinterpreting the event or debated whether the victim was to blame. Once a student had disclosed and determined that the response was ineffective, they were less likely to report future incidents.

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of peer victimization and institutional betrayal are apparent in that neither falls under the official PTSD Criterion A requirement. This may lead to multiple obstacles such as an onslaught of diagnoses that impede treatment, incorrect or incomplete treatment, and incorrect or incomplete diagnoses. One of the main uses of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) is for insurance purposes. This allows for affordable treatment, and official recognition and documentation of the outcome of a victim’s experience. Both of these are important in relation to receiving treatment, but also working on easing another betrayal trauma from healthcare institutions. Not being acknowledged by another set of officials who have the power to provide assistance can constitute another institutional betrayal.

Clinical implications may cascade into policy implications as well. Official documentation may also require the school to respond to an incident as effectively as possible, such as amendments to codes of conduct and disciplinary actions. This in turn could reduce the extent of institutional betrayal on a case by case basis, but also work toward resolving the root issue of peer victimization.

Diagnostic Solutions

There are multiple considerations in searching for possible solutions concerning an official diagnosis. There is debate about the limitations of the PTSD diagnosis, especially the constitution of Criterion A. Other commonly explored diagnostic solutions are complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder (DTD).

Complex PTSD refers to the experience of survivors of prolonged and repeated traumas, and can consist of symptomatology that differs from PTSD (McDonald et al., 2014). While symptoms include the amplification of PTSD symptomatology, survivors of complex PTSD may also experience changes in relationships (i.e., fluctuations between healthy and unhealthy attachment and withdrawal). Bullying is defined as a kind of aggressive behavior involving repeated negative actions over time by a perpetrator against an individual who cannot defend themselves (i.e., a power imbalance) (Idsoe et al., 2012). This supports the notion that peer victimization is not only linked to the current PTSD diagnosis, but common reactions to peer victimization fulfill requirements for a new or revised PTSD criteria implementing consideration of complex PTSD.

DTD is a proposed clinical diagnosis that was previously considered but ultimately denied inclusion in the DSM-5. The American Psychiatric Association’s defense was that the idea that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) could lead to substantial developmental disruptions was more “clinical intuition” than evidence-based fact (van der Kolk, 2014). However, research has shown that ACEs, which include bullying, can have negative effects on brain development. Other research on ACEs have shown that distressing events can lead to symptoms similar to PTSD (Ossa et al., 2019). Previous targets of school bullying are at a higher risk for poor general health and have greater difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships.

In the DSM-5, there are specifications for children under six in the PTSD diagnosis. These include slightly different symptoms or presentation of PTSD symptoms. Van der Kolk (2014) writes that PTSD symptoms along with the specifications for early childhood trauma can be fully explained by a diagnosis of DTD. McDonald and colleagues (2014) conducted a study measuring potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs), and whether these experiences were predictive of a distinct set of symptoms characteristic of DTD. Bullying (physical, relational, verbal, and cyber) was included on the list of PTEs. Results confirmed a substantial amount of distressing life events that occur during childhood and adolescence. They also support future revision of the DSM-5 to include a developmentally-focused diagnosis for PTSD-like symptoms that do not necessarily meet PTSD Criterion A.

Conclusion

Institutional betrayals reach as far as one’s local schools. Peer victimization has been further impacted by institutional betrayal and is a national problem. Reports of peer victimization often go unaddressed, and if they are addressed it is not usually an effective response. This ineffectiveness on account of the people and institutions that hold the power to address bullying poses as a form of institutional betrayal. This leads to many victims of bullying to also experience a second form of trauma in institutional betrayal.

Both peer victimization and betrayal trauma are linked to post-traumatic stress reactions, but neither are officially listed in the criteria required for a clinical PTSD diagnosis. This has led research to explore the clinical implications for people who experience traumas not listed in the PTSD Criterion A requirement, and possible solutions. Possible solutions include three revisions of the DSM-5 to include at least one of the following: 1) a revision of PTSD Criterion A to include traumatic events not currently listed, 2) the addition of complex PTSD, or 3) the addition of a developmentally-focused diagnosis for post-traumatic stress reactions that do not fall under PTSD Criterion A.

References

Bjereld, Y., Daneback, K., & Mishna, F. (2019). Adults’ responses to bullying: The victimized youth’s perspectives. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1646793

Freyd, J. J. (2020). What is a betrayal trauma? What is betrayal trauma theory? Freyd Dynamics Lab. http://pages.uoregon.edu/dynamic/jjf/defineBT.html

Freyd, J. J., & Birrell, P. (2013). Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled. John Wiley & Sons.

Gordon, S. (2020, April 02). How bullying can lead to ptsd in kids. Very Well Family. https://www.verywellfamily.com/bullying-can-lead-to-ptsd-460614

Gušić, S., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H.P. (2016). Types of trauma in adolescence and their relation to dissociation: A mixed methods study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 568–576. http://dx.doi.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000099

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Idsoe, T., Dyregrov, A., & Idsoe, C. E. (2012). Bullying and ptsd symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 901-911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9620-0

McDonald, M. K., Borntrager, C. F., & Rostad, W. (2014). Measuring trauma: Considerations for assessing complex and non-ptsd criterion a childhood trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867577

Ossa, F. C., Pietrowsky, R., Berin, R., & Kaess, M. (2019). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among targets of school bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0304-1

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). Developmental trauma: The hidden epidemic. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

The Lone Child (Children at the Southwest Border)

The Lone Child

Fall of 1995, my two (2) brothers and I came to this country from the Dominican Republic with my late grandmother. I remember that day as if it was yesterday. Waking up bright and early, driving to the airport, and going inside that plane was exciting but scary. I remember my grandmother clenching my hand as the airplane took off from the runway and my ears popping as the airplane reached a higher elevation. Once we landed, I was amazed with the airport and size of the buildings around New York city. It was one of the best days of my life.

Unfortunately, not every child has had the same experience. The United States’ southwest border has seen a spike in families attempting to cross the border into the United States from South America. These families leave their homes, walk hundreds of miles, and even pay “coyotes” to smuggle them across the border. A “coyote” is an individual who works for an organization who are dedicated to smuggling humans across the border. These families risk everything they have and leave their homes in a pursuit of a better life. Unfortunately, after paying the coyote a quantity of money, the families are either defrauded or just dumped somewhere near the border to fend for themselves. These families are then forced to walk and go through dangerous situations that can cause negative lifelong effects on their children and themselves.

When crossing the border, families also risk being detained by Homeland Security agents guarding the border and risk having their children separated. Some children have been seen arriving to the border with no adult present. These children have been known to suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders, that affect their mental health in the long run. According to the American Psychological Association, “PTSD symptoms were significantly higher for children of detained and deported parents compared to citizen children who parents were either legal residents or undocumented without prior contact with immigration enforcement. (Nami,Martinez, 2021)” Further research shows that these children remain fearful that there will be another time where they are separated from their parents.

The detainment of migrant children and separation from their parents has caused heated debates amongst Americans. As mentioned above, the separation of a child from its parents can cause long lasting effects but how do we prove that these children belong to these individuals identifying themselves as the parents or guardians? Coyotes have also been known to sexually traffic juveniles into the United States for profit. Our society has seen many Human Trafficking cases coming from different countries and entering the United States. What do we need to do to better handle migrant children entering the country without a parent or guardian present?

(National Alliance Mental Illness, 2021)

(National Alliance Mental Illness, 2021)

As of now children who are separated from their parents are held at in holding facilities with other children. While in detention, Custom Border Protection agents determine if the child qualifies as an unaccompanied child. While waiting, these children can be placed into shelters, foster homes, group homes, etc.

While the government attempts to figure out what the child’s verdict should be, I believe we should invest into these holding facilities, group homes, foster homes, etc to make sure these children are receiving the care they need. Providing a good nutritional meal, exercise, living conditions, and education, can alleviate the PTSD or trauma a child may be dealing with. Providing video conference calls with families back home or in the United States can also assist in the process while they wait for the courts to proceed. We should further invest in counseling for these children who are held in these facilities. Attempting to figure out the problems and motivation for attempting to cross the border will help us understand how to help these families. Another way to help alleviate the stress and trauma in these children is to provide better funding for the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

The ORR is an organization where migrant children are sent to. Unfortunately, these facilities are separated and miles away from where the child’s parents might be being held. Providing funding for more southwest border locations will prevent children from being separated and keeping them closer. The farther away a child is from their parents, the better chance for that child to lose contact. Another way to alleviate the trauma is to transform these holding facilities into more welcoming, hospital like locations and not so much like a prison.

In conclusion, while I understand that migrants are attempting to enter the country at record breaking numbers, the United States must do their best to understand why these people are attempting to enter. Let’s provide better funding for the facilities near southwest border. Turn these facilities into hospitals and triage centers that better evaluate family relationships and the vetting process. Evaluating family relationships as fast as possible will prevent families from having to be broken up. This is an issue that is never going to stop, so instead of trying to stop it, let’s figure out a way to make it better and less harming.

References

Children are still being separated from their families at the border. Vera Institute of Justice. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.vera.org/news/children-are-still-being-separated-from-their-families-at-the-border

Council on Foreign Relations. (n.d.). U.S. detention of child migrants. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-detention-child-migrants

Trauma in children of Latinx immigrants. NAMI. (n.d.). Retrieved August 9, 2022, from https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/February-2021/Trauma-in-Children-of-Latinx-Immigrants

Trauma…the good, the bad, and the ugly

What comes to mind when you hear the word “trauma”? Most often we associate it with negative feelings/emotions of pain, sadness, harm, and struggle. What if I told you that the trauma experiences that I have dealt with in life have enabled me to grow and learn about myself? I would like to talk about post traumatic growth. In my experience trauma can either disable you or motivate you. I experienced trauma as a child which had formed my outlook on life. Sometimes those habits are hard to break. However, it wasn’t until my adult trauma’s that I began to understand what makes Meredith tick. Trauma experiences as a child are not easy to process as children don’t have the knowledge and coping mechanisms that can be developed in adulthood.

In 2013, I traveled by commuter train to Boston to watch a friend run the Boston Marathon. I had run it the year before. I had taken up a “home base” at the Atlantic Fish Company on Boylston Street very near the finish line. In the passing time, I had unknowingly walked by both bombs within a very close time of them detonating. I had only been inside the restaurant for a minute or so when I heard the first bomb explode and felt the ground shake. My first inclination about what it may have been was maybe the catwalk or stands had collapsed at the finish line. That first explosion drew my attention out the plate glass window in the front of the restaurant and that is when I saw a flash and heard another explosion. Right then, from my training and experience, I knew they were bombs, and it was terrifying.

Through my fears, my training and experience as a State Trooper took hold. I immediately went into work mode and ushered people into the basement floors of the restaurant. People were streaming in from the street outside and were hysterical, I tried to provide them comfort. I subsequently exited the restaurant and saw a man with no leg. I assisted in grabbing tablecloths and ice from inside the restaurant, bringing them outside to aid the injured. I saw a man sitting over young Martin Richard. He looked at me and I looked at him and we knew he was dead. That picture is forever engrained in my mind. I then saw two men carrying his sister, toward an awaiting Rescue. The response to the tragedy was extremely fast as there were Rescue personnel already on standby at the finish line for runners. As a law enforcement officer, we call this “controlled chaos”. This controlled chaos are the situational conditions that we have been trained to handle. Rescues, doctor, nurses were right at the finish line to assist the finishing athletes, little did they know they would have a much different task that day.

Although I sought out therapy for what I experienced, I didn’t do enough work. I was back to work quickly to avoid watching the media attention, and subsequently dealing with the stressors of work on top of what I had experienced in Boston. A couple years later I found myself in an abusive relationship and it was during this time I can now see that I fell into a steep downward spiral. In 2017 I had to have shoulder surgery from a dislocated shoulder suffered while hiking in Vermont. I had been in Vermont at a program for first responders suffering from addiction/substance abuse. Yes, I had found solace in the bottom of a liquor bottle like many first responders. After surgery, I voluntarily admitted myself into a 30-day residential treatment program in Michigan for those suffering from addiction and co-occurring disorders. It was the best decision I have ever made. For those of you that have never experienced an inpatient treatment program, you are essentially cut off from the rest of the world. No cell phones, no internet, no television. Your immediate job is to address yourself while removing outside influences and stressors so that you can concentrate on yourself. Often throughout life, addressing our inner being is the last thing on a list of many things to do. Yet it is the most crucial thing for our overall wellbeing.

Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) can occur from any experience that challenges your core values and beliefs about the world: what you’re capable of, the nature of the world, the nature of others, and your philosophy about life. (HPRC, 2022) Studies have found that more than half of all trauma survivors report positive change—far more than report the much better-known post-traumatic stress disorder. (Rendon, J., 2015) Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is a theory that explains this kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s, and holds that people who endure psychological struggle following adversity can often see positive growth afterward. (Collier, 2016)

People who have experienced trauma must decide whether that trauma will define them or control them. That decision is most often made unconsciously. I would argue that part of PTG is bringing that unconscious thought to conscious action. That decision is made based on the experience at the time and place that the individual occupies. The decision is often uncontrollable, until you figure out what makes you “tick”. Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom. (Pattakos, A., Dundon, E., 2017) Tedeschi, the leading psychologist in PTG, stated, “we’ve learned that negative experiences can spur positive change, including a recognition of personal strength, the exploration of new possibilities, improved relationships, a greater appreciation for life, and spiritual growth. (Tedeschi, 2020)

In my experience, I have grown to learn more about myself in my 40’s then I have in my entire life. That is not to say that it didn’t take work. When you find yourself stuck and realize that it is time to take time for you, I can say it is a freeing experience. Like many others, I found it extremely difficult to say “no”. Learning to say “no” can be exhilarating. PTG is life changing. It’s important to understand and accept that our life experiences may influence our actions and beliefs, but they don’t need to control us. Having a clear mind to rationally attack life’s “bumps in the road” is necessary for this growth. In my experience, PTG has forced me to try new things, brought what is important into perspective, gave me a new perspective on things, allowed me to grow as a person, forced me out of my comfort zone, provided me with a new understanding on others experiencing trauma, and made me realize that I am human. Through PTG you begin to understand just what resilience is and how we can increase our tolerance of uncomfortable things. Resilience is a crucial protective factor in the individual that resists the influence of multiple risk factors. (Bartol & Bartol, pg. 37, 2021) Resilience defined is successful coping with or overcoming risk and adversity, the development of competence in the face of severe stress and hardship, and success in developmental tasks or meeting societal expectations. (McKnight & Loper, 2002, pg. 188)

Furthermore, we all need to learn to listen to our bodies. It is the first indication that something is amiss, and we all too often ignore the signs. Being able to detect even slight changes in our bodies can help us to recognize what we are experiencing and assist us in making better decisions. Learning through mindfulness to be present in the moment. It is imperative that we make time for ourselves, however small time that may be. It is crucial to our wellbeing.

Bartol, C., & Bartol, A. (2021). Criminal behavior: A Psychological Approach (12th ed.). Boston.

Collier, L. (2016, November). Growth after trauma. Monitor on Psychology. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/11/growth-trauma

Human Performance Resources by CHAMP (HPRC), 5 benefits of post-traumatic growth. (2020, September 11). Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://www.hprc-online.org/mental-fitness/mental-health/5-benefits-post-traumatic

McKnight, L.R., & Loper, A.B. (2002). The effect of risk and resilience factors on the prediction of delinquency in adolescent girls. School Psychology International, 23, 186-198.

Pattakos, A., & Dundon, E. (2017). Prisoners of our thoughts: Viktor Frankl's principles for discovering meaning in life and work. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Rendon, J. (2015, July 22). How trauma can change you-for the better. Time. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://time.com/3967885/how-trauma-can-change-you-for-the-better/

Tedeschi, P. G. (2020, August 31). Growth after trauma. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved August 10, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2020/07/growth-after-trauma

Transitional Shift in Criminal Justice Proceedings

Criminal justice and the study of deviant behaviors has seen many paradigms shifts since its inception. From the pseudo-science of phrenology to the cruelty of the Pennsylvania prison model, these non-evidence based approaches to criminal justice has brought tangible harm countless victims.

If we presuppose that the aim of criminal justice is to reduce the likelihood of offender recidivism then this premise will provide us with some indicia of how the current systems are performing. The adversarial model of criminal justice is widely accepted in western societies as both familiar and entrenched in tradition. In this model, criminal matters are deemed settled when the offender in question is assigned a specific punishment for their respective transgressions. (Maschi, 2014) Punishment is nearly universally limited to housing individual offenders within a prison facility based on their respective criminal offence and risk based demeanor. This punishment serves the dual purpose of incapacitating a specific offender for a determinate period of time and acting as a deterrent to the overall public. Administratively, this process of criminal justice is unaffected by the desires of the victims, it does not seek to make the community whole nor does it attempt to make the offender understand the deleterious nature of their action. The most damning condemnation of the adversarial model of criminal justice is that it fails to transform offenders into law-abiding citizens after their institutionalization. Statistically, once a prisoner has been released from an in custody facility there is an approximately 50 percent chance that they will be reconvicted of a criminal offence within 3 years. (Nagin et al., 2009) This data is relatively consistent over multiple countries that employ a western model of criminal justice. Within the United States, the issue of recidivism is further exacerbated by the mass incarceration rates, which shows that around 2.3 million Americans are in some form of custody. (Nagin et al., 2009)

As presently constructed, the adversarial model of criminal justice employed in the United States has undoubtedly failed in its raison d’etre. Based on the statistics mentioned above, we can extrapolate that the economic burdens along with the sheer concentration of human suffering produced far outweighs any actual benefits derived.

So where do we go from here? If we concede that rehabilitation is the central component to the process of obtaining justice, we have no alternatives but to evoke a radical paradigm shift towards a truly restorative justice model.

Restorative Justice Principles as imagined by early proponent Howard Zehr is based less in the procedure of jurisprudence and focuses more on the communal effects of crime. (Maschi, 2014) Victim Offender Mediation open up the pathway of healing for both parties involved in a crime. The victim who was wrong is allowed to speak their feelings and the offender is able to see how their actions affect the community as a whole. Contrary to popular opinion, this system of justice produced through a sentencing circle provides both accountability of offenders and can utilize punishment other than imprisonment. Evidence surrounding restorative justice system shows strong reduction in decreased recidivism and an increase compliance with other forms of restitution. (Maschi, 2014)

Critiques against transitioning to a Restorative Justice System can come from multiple approaches. Pragmatically, an overhaul of the current system is seen by many as unnecessary given the presence of the adversarial model. However, this argument is academically inadequate because it is rooted in a lack of understanding rather than conveying any tangible benefits of the current systems. As a scientific field, criminal justice should seek to continuously improve upon it systems based on evidence supported by new research. Furthermore, with shifts towards specialized courts for individuals of the following categories veterans, drugs and mental health patients we are seeing a natural progression towards restorative justice practice as a society.

Another common critique levied by advocates against restorative justice model is that this type of proceeding is suitable only for minor offences. However contrary to this belief, New Zealand operationalized restorative justice conferences for serious violent offenders with police diversion reserved for minor offences. (Morris, 2002) Research results demonstrates that in comparison with a control group of similar offenders a marked improvement is observed from the conventional criminal justice proceeding. (Morris, 2002)

Moving towards new systems of criminal justice can be daunting however, this alone should not be the reason progress is halted. There is an ethical imperative for practitioners and professionals to call for a reformation of the current criminal justice system towards an institutionally restorative model.

Work Cited

- Maschi, T., Leibowitz, G., & Mizus, L. (2014). Restorative Justice. In L. Cousins (Ed.). Encyclopedia for Human Services and Diversity (pp. 1142-1144). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Wenzel, M., Okimoto, T. G., Feather, N. T., & Platow, M. J. (2008). Retributive and restorative justice. Law and Human Behavior, 32(5), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-007-9116-6

- Nagin, D. S., Cullen, F. T., & Jonson, C. L. (2009). Imprisonment and reoffending. Crime and Justice, 38(1), 115–200. https://doi.org/10.1086/599202

- Morris, A. (2002). Critiquing the critics: A brief response to critics of restorative justice. British Journal of Criminology, 42(3), 596–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/42.3.596

Self Care In the Criminal Justice Field: Pushing for Support

"Dark humor- it's just how we cope".

If you were to mention the topic of "self-care" to a room full of varying Criminal Justice professionals, chances are you will be laughed at. Immediately, and not necessarily openly, many would cite their coping skills and self-care methods as dark humor, drinking, and a lack of steady relationships and it would be welcomed and just considered to be part of the "norm". Self-care certainly has not been made a top priority in several areas of the Criminal Justice field such as within law enforcement, corrections, and even dispatch.

While this course has been aimed at better understanding forensic psychology, it has also given students the opportunity to take on and recognize the topic of self-care, hopefully instilling its importance in the long run. We know how deeply trauma can affect humans, and we often are taught to look for the signs in the people we work with. What isn't emphasized, however, is how to recognize the residual effects of the trauma we see and work within our lives. That is why self-care is so important! What is self-care, anyway? Well, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, self-care is "...taking the time to do things that help you live well and improve both your physical health and mental health" (NIMH, 2022). Some ways to achieve self-care include exercising, getting enough sleep, engaging in positive activities that promote deeper connections, and more. One of the biggest steps to self-care is recognizing the need for it and actively making the choice to pursue it! By making self-care and your mental health a priority, we hope to see less burnout and fewer people actively struggling, which then impacts their work, personal lives and so much more.

A FOCUS ON SELF CARE DOES NOT MAKE YOU WEAK.

Please see some of the below links for resources on mental health and self care.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Caring for your mental health. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved August 14, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/caring-for-your-mental-health

https://www.everydayhealth.com/self-care/

https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/res-rech/p5.html

Megan Downing

Addressing the Victim to Offender Cycle

Throughout this semester in our class discussions, I have spoken in fragments about my experience working with child victims of sexual abuse. In one particular post, I spoke with another classmate about the unfortunate cycle of victim to perpetrator, which I would like to address later in this post. To first provide some background on my experience, a few summers ago I interned with my prosecutor's office special victims unit. As this was during the height of COVID, my responsibilities as an intern were unconventional. My primary responsibility was to help digitize old case files from previous years. As a result, I spent a lot of time handling files of cases from years prior. During this assignment, I came to the frightening realization of how commonplace these occurrences are. To that extent, my entire worldview began to shift when I realized I was in one county, of one city, of one state, of an unfathomably large world.

As a second responsibility, I was tasked with sitting in on victim interviews. To be more specific, while an SVU detective would interview a victim, I and one or two other staff would sit in another room that provided a live visual and auditory feed of the interview. I was charged with taking notes and documenting body language or subtle cues that the detective may have missed. As I sat in on these interviews and heard in real time these emotional and unsettling testimonies from children, a callous and apathetic outlook of offenders began to form.

I have often heard and echoed the notion that children, boys in particular, who are the victims of sexual assault, are now at a greater risk of committing the same act. Upon further research into the subject, I have learned that this sentiment actually does more harm than good to survivors of sexual abuse. The “victim to offender cycle” is complex and can not be simplified to such a degree. To understand the complexity and nuances of the cycle, we must review the research on sexual offending. First, the gender of the offender: males commit roughly 80% of offenses among boys and 96% of offenses among girls (2018). Second, risk factors of adults who have offended, these individuals tend to:

“Show greater aggression and violence, non-violent criminality, anger/hostility, substance abuse, paranoia/mistrust, and have diagnosable antisocial personality disorders… Be more likely to show anxiety, depression, low self-esteem… Generally have more problematic sexual patterns (including fantasies and sexualized coping strategies)... Have low social skills/competence… Have poorer histories of family functioning, including more harsh discipline, poorer attachment or bonding, and generally worse functioning of their family of origin, including physical abuse, and sexual abuse…” (2018).

The reality is, there are many factors at play regarding sexual offending. Significantly, research suggests that most men who have committed an offense were not sexually abused previously. Therefore, an important distinction must be emphasized between “risk” and “causation” — for those who are at a “higher risk” for later offending does not mean their victimization will be the one and only “cause”. A study in the UK that examined future offending in boys who were sexually abused found that 88% did not go until commit any sexual offenses (2018).

The streamlined ideology of “victims are now likely to be offenders later in life” is ubiquitous in our society. This creates a stigma for survivors. If you are the victim of abuse, in speaking about your experience, you may also be labeled as “someone who is likely to offend”. As a result, a victim might refrain from disclosing their abuse due to the fear of being viewed as a potential offender (2018). This ideology can also generate thoughts and feelings in survivors of being “contaminated” or the “vampire effect”. Specifically, boys and young men may feel the need to be hyper-vigilant of their own thoughts or feelings for fear that they may become “possessed” (2018). Besides being victimized, this dread of later offending has interpersonal ramifications such as “developing intimate relationships, marrying, having children, becoming fully involved in parenting, bathing or changing the nappy of their children, playing with or coming into contact with children, from relaxing, and from trusting in themselves” (2018).

As I mentioned previously, I too have contributed to this misconception. Unfortunately, it is a widely uncontested and accepted notion. However, the propagation of this idea does harm to actual survivors. This idea continues to persist because of its simple form factor. Unfortunately, it is easier to tolerate and believe this idea rather than the fact that we live in a world where people make the intentional decision to sexually abuse a child.

References

Addressing the victim to offender cycle. Living Well. (2018, February 13). Retrieved August 14, 2022, from https://livingwell.org.au/managing-difficulties/addressing-the-victim-to-offender-cycle/

Inherent Racism in Lack of Preventative Programming for At-Risk Youth

“It Is Easier to Build Strong Children than to Repair Broken Men” – Frederick Douglass

The seeds of crime are sown long before the first dollar is stolen, drug is sold or life is taken. Risk factors such as poverty, peer rejection, antisocial peers, inadequate after-school care and poor academic performance – not mention abusive or neglectful parenting and psychological maladies – can set a child on a course to antisocial and/or criminal behavior. The combination of multiple risk factors working together further compounds the probability; the developmental cascade model helps illustrate just how the interaction of negative and often traumatic experiences carve out a trajectory to crime by strengthening, influencing or informing subsequent skills and deficits (Bartol & Bartol, 2017). Sadly, children across the country are wrestling with plural risk factors every day. A national sample of children recently found that nearly 40 percent of children in American had been direct victims of multiple violent acts (2020b), one in five students report being subjected to bullying (2020a) and 11.6 million children just two years ago were found to have been living in poverty (2021). That is a lot of children with a lot of risk factors. And that is the bad news.

The good news, however, is that protective factors can create a metaphorical U-turn in this pathway, providing positive intermediaries for the negative conditions. One such factor is early childhood education. Quality education has been proven to reduce the likelihood of future criminal behavior, with children in satisfactory schools exhibiting no more behavior issues at age eight than those with college-educated mothers (2018). The Perry Project is one such program, an educational intervention first established as a study examining the effects of high-quality preschool on at-risk children and their communities. Based on the HighScope strengths-based learning approach, the analysis concluded that by age 40, low-income children who attended competent preschool programs enjoyed greater financial earnings, had greater potential for employment, experienced less criminal involvement and were more likely to have completed high school (2004). Conversely, research on government-funded Child-Parent Centers in Chicago found children excluded from the program 70% more apt to be arrested on charges of violent crime by age 18 and five times more likely to experience chronic crime-involvement by adulthood (2018).

This buffering effect of early education on children with developmental risk factors is widely accepted, roughly nine out of ten police chiefs agreeing that expanding quality childcare programs would significantly reduce crime (2018). Additionally, Sanford Newman, president of anti-crime organization Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, stated, “Law enforcement leaders know that to win the war on crime, we need to be as willing to guarantee our kids space in a pre-kindergarten program as we are to guarantee a criminal a prison cell” (2004). And as Joe Biden’s $775 billion child and elder care plan proposes universal preschool for three-and four-year-olds (2020d), things should be looking up for both children and the criminal justice system.

But there is a catch. A report by the Education Trust shows only one percent of Latino and four percent of Black children in 26 U.S. states are enrolled in “high quality” state-funded early learning programs (Ujifusa, 2019), blaming accessibility and affordability for the imbalance. The problem, it argues, is that states with better programming fail to reach their BIPOC children, and other states with higher percentages of children of color provide relatively lower-quality services. Meanwhile, nationwide statistics show that 30 states sustain a significant imbalance between enrollment of white children versus lower percentages of Latino children, and 18 states wherein white children are enrolled significantly higher than Black children (Hardy & Huber, 2020). The disparity is exacerbated by the fact that peer enrollment often has an impact on participation of other children (Hardy & Huber, 2020), so barriers to some can often mean barriers to many.

The question remains: why are adequate early learning resources less available to marginalized communities? Author Linda Darling-Hammond explains that it is a common fallacy that children of color and/or from disadvantage simply do not have the capacity to make good use of education (Darling-Hammond, 2001); from as long ago as the 1960s, Black children were viewed as socially, culturally and financially bereft, and, thus, in need of “fixing” (Allen, 2021). So affordable, accessible preschool for the BIPOC community has not gotten the funding nor attention it so desperately needs. And the very reason these resources remain sparse is the same reason why they are so needed; the Education Trust concluded in its report, “Systemic racism causes opportunity gaps for black and Latino children that begin early—even prenatally, which makes it crucial for these families to have access to high-quality [early childhood education] opportunities as a pathway to success into their K-12 education” (Ujifusa, 2019).

The need is becoming increasingly more urgent. As of last year, Black children were more than four times as likely to be held in juvenile facilities than their white counterparts (Rovner, 2021) and Latino youth 28 percent more likely (Bagley, 2021), even though adequate early education could help reduce this inequity and give children of color the possibility of success they have deserved all along. Naysayers argue that the cost of investment is simply too high, a familiar fallback excuse to continue inaction. But according to the Justice Policy Institute, incarcerating a single youth currently costs $588 per day, or $214,620 per year (2020c), whereas quality prekindergarten would virtually pay for itself by 2050 by yielding $8.90 in benefits for every dollar invested, $304.7 billion in benefits in total (Lynch & Vaghul, 2015). While these numbers may be overwhelming (to digest, not to mention decipher), the key point is this: quality, government-funded early childhood education would ultimately pay its taxpayers back in total, and the societal boon would manifest in reduction of crime, less incarceration and more citizens contributing to the welfare and economy of their communities.

The arguments are sound, the numbers add up, but racism rarely hears more than a dog whistle. It is up to those in the criminal justice field to implement these changes to give youth – and the adults they will become – a chance to thrive.

References:

Allen, R., Shapland, D. L., Neitzel, J., & Iruka, I. U. (2021). Viewpoint. creating anti-racist early childhood spaces. NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/summer2021/viewpoint-anti-racist-spaces

Bagley, N. (2021, July 23). Latinx disparities in youth incarceration. Youth Today. https://youthtoday.org/2021/07/latinx-disparities-in-youth-incarceration/

Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2017). Criminal behavior: A psychological approach (Eleventh). Pearson.

Bullying statistics. PACER Center - Champions for Children with Disabilities. (2020, November). https://www.pacer.org/bullying/info/stats.asp

Children exposed to violence. Office of Justice Programs. (2020, January 8). https://www.ojp.gov/program/programs/cev

Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). Inequality in teaching and schooling: How opportunity is rationed to students of color in america. In B.D. Smedley, A.Y. Stith, L. Colburn & C.H. Evans (Eds.), The right thing to do, the smart thing to do (pp. 208-366). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223633/ Doi: 10.17226/10186

Hardy, E., & Huber, R. (2020, January 15). Neighborhood preschool enrollment patterns by Race/ethnicity. diversitydatakids.org. https://www.diversitydatakids.org/research-library/data-visualization/neighborhood-preschool-enrollment-patterns-raceethnicity

Highscope Perry Preschool study. HighScope. (2004, November). https://highscope.org/highscope-perry-preschool-study/

The link between early childhood education and crime and violence reduction. Economic Opportunity Institute. (2018, October 17). https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/early-learning/ELCLinkCrimeReduction-Jul02.pdf

Lynch, R., & Vaghul, K. (2015, December 2). The benefits and costs of investing in early childhood education. Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/the-benefits-and-costs-of-investing-in-early-childhood-education/?longform=true

New Child Poverty data illustrate the powerful impact of America's safety net programs. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021, September 20). https://www.aecf.org/blog/new-child-poverty-data-illustrates-the-powerful-impact-of-americas-safety-net-programs

Rovner, J. (2021, July 15). Black disparities in youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/black-disparities-youth-incarceration/

Sticker shock 2020: The cost of youth incarceration. Justice Policy Institute. (2020, July 30). https://justicepolicy.org/research/policy-brief-2020-sticker-shock-the-cost-of-youth-incarceration/

Ujifusa, A. (2019, November 6). Kids of color often shut out of high-quality state preschool, research says. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/kids-of-color-often-shut-out-of-high-quality-state-preschool-research-says/2019/11

USAFacts. (2020, October 16). Pre-primary enrollment statistics among three- and four-year olds. USAFacts. https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-children-attend-preschool-us/