Feminism in the Penal System

Feminism in the Penal System

One topic of consideration from the class is the role of feminism in treatment options and the criminal justice system generally. Further, how new research, focused on the challenges women face in correction, has resulted in several beneficial treatment options with greater efficacy. This blog post will expand on several concepts from class, with a focus on the common thread of how the system is addressing women’s issues.

I want to further explore the field of Gender Responsive Programming. Dr Rousseau, synthesizing the work of Dr Gilligan, wrote: “women’s distinct moral development results in an ‘ethic of care’ or a very relational way of decision making and interacting with the world. Relational theory is based on this idea that women interact with the world in an interconnected capacity. Women develop a sense of self and self-worth where their actions arise out of and lead back to connections with others. Here, theory suggests that women, more so than men, are likely to be motived by connect and relationships. For example, women are more likely to turn to drugs or to engage in drug-related crime in the context of a relationship. Women’s psychological growth and health is tied to this sense of connection. Because of this, group treatment is frequently an effective strategy for women offenders” (2021, Rousseau). This is ultimately a theory based on evidence and one that is developed by mostly female practitioners in a women’s prison to address the unique issues facing women. One of the best findings from this is how much more successful Group Therapy is for women than for men. And this is consistent with their theories of relational interconnectedness.

Women and children are particularly vulnerable to physical violence and unfortunately, more susceptible to trauma-related injuries. Women are twice as likely to get PTSD as men (VA, 2020). The American Psychological Association defines trauma as “an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape or natural disaster. Immediately after the event, shock and denial are typical. Longer term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships and even physical symptoms like headaches or nausea.” (APA, 2020) The symptoms in children include phobia development, separation anxiety, sleep disturbance, nightmares, sadness, loss of interest in normal activities, reduced concentration, decline in school work, anger, somatic complaints, and irritability (APA, 2020). With the new research focusing the role of gender in susceptibility to trauma, more research should be done on ways to prevent such trauma and better ways to treat it with a focus on the new realities of the victims of trauma. It’s not just soldiers in war who get PTSD.

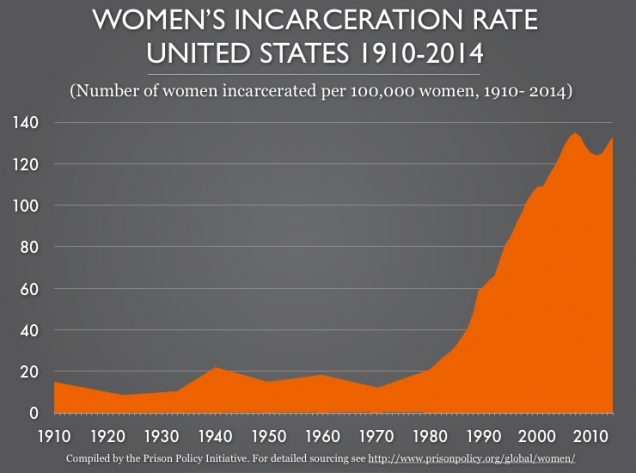

Another issue that is unique or more pronounced for women is what to do when a woman gets pregnant in prison. Naomi Riley notes in the article On Prison Nurseries that, “An estimated 6–10% of women are pregnant upon incarceration” and “are more likely to have been their child’s primary caregiver before their last arrest” (Riley, 2019). Women are the fastest growing demographic to face incarceration (Goshin, 2013). Therefore, it is more important now than ever for states and the Department of Justice to have a proper solution that balances the needs of society, the mothers, and the children. Ultimately, prisons must retain their deterrent quality and should not be punishing innocent children. Criminologist Joseph Carlson was a supporter of prison nurseries. He wrote, “Many studies have shown that maternal deprivation affects children. Young children who are removed from their mothers for hospitalization or other reasons display immediate distress, followed by misery and apathy” (Carlson, 2000).

In conclusion, whether it is Group Therapy, Relational Theory, Gender Responsiveness Programming, PTSD in women, or prison nurseries, there are many developing and worsening issues that effect female populations that should be given greater consideration in research. It is one of the newest fields on criminological research. Nevertheless, it has already been incredibly fruitful.

References

APA. (2011). Children and Trauma. Accessed at https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/children-trauma-update

Bloom, B. E., & Covington, S. S. (2008). Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders. In Women’s mental health issues across the criminal justice system. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Bloom, B. E., Owen, B., & Covington, S. S. (2003). Gender-Responsive Strategies: Research, Practice, and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders. National Institute of Corrections. Retrieved from https://nicic.gov/gender-responsive-strategies-research-practice-and-guiding-principles-women-offenders

Carlson, Joseph. Prison Nursery 2000: A Five-Year Review of the Prison Nursery at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women. US Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ojp.gov/library/abstracts/prison-nursery-2000-five-year-review-prison-nursery-nebraska-correctional-center

Gilligan, C. (1993). In a Different Voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goshin, L. S., Byrne, M. W., & Henninger, A. M. (2013). Recidivism after Release from a Prison Nursery Program. Public Health Nursing, 31(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12072

Riley, Naomi. On Prison Nurseries. (2019). National Affairs. https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/on-prison-nurseries

Rousseau, D. (2021). Module 4 Study Guide. Forensic Behavior Analysis. Boston University.